Abstract

Background:

Head and neck cancer (HNC) patients are prone to have a poor health-related quality of life after cancer treatment. This study investigated the effect of the nurse counselling and after intervention (NUCAI) on the health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms of HNC patients between 12 and 24 months after cancer treatment.

Methods:

Two hundred and five HNC patients were randomly allocated to NUCAI (N=103) or usual care (N=102). The 12-month nurse-led NUCAI is problem-focused and patient-driven and aims to help HNC patients manage with the physical, psychological and social consequences of their disease and its treatment. Health-related quality of life was evaluated with the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ H&N35. Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the CES-D.

Results:

At 12 months the intervention group showed a significant (P<0.05) improvement in emotional and physical functioning, pain, swallowing, social contact, mouth opening and depressive symptoms. At 18 months, global quality of life, role and emotional functioning, pain, swallowing, mouth opening and depressive symptoms were significantly better in the intervention group than in the control group, and at 24 months emotional functioning and fatigue were significantly better in the intervention group.

Conclusion:

The NUCAI effectively improved several domains of health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in HNC patients and would seem a promising intervention for implementation in daily clinical practice.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, health-related quality of life, depressive symptoms, psychosocial, intervention, nurse

Head and neck cancer (HNC) patients experience a deterioration of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) directly after they start treatment and up to 1 year after treatment (Rogers et al, 2007), and possibly for much longer (8–11 years) after treatment completion (Mehanna and Morton, 2006; Oskam et al, 2013). Health-related quality of life is multidimensional and includes generally experienced QoL, functioning (e.g., emotional and physical functioning), general cancer symptoms (e.g., fatigue and pain) and cancer-specific symptoms (e.g., in HNC problems with swallowing and dry mouth). Depressive symptoms at diagnosis are known to be predictive of a poor HRQoL 1–3 years later (Hammerlid et al, 2001; Ronis et al, 2008). The need for effective interventions to improve HNC patients' HRQoL has been emphasised in the literature (Semple et al, 2009; de Leeuw et al, 2013; Hong et al, 2013), but there have been few high-quality studies investigating the long-term effect of interventions on HRQoL in HNC patients.

Nurses are in a key position to deliver an intervention to improve HRQoL (Kagan, 2009; Penner, 2009). They are already involved in patient care and have the necessary skills and knowledge about the medical and practical aspects of HNC treatment and its consequences. In addition, nurses can provide information, support and coaching to HNC patients (Wells et al, 2008; Eades et al, 2009; de Leeuw et al, 2013). We therefore designed a longitudinal randomised controlled trial (RCT) to investigate the effectiveness of a comprehensive 1-year nurse-led intervention, the nurse counselling and after intervention (NUCAI), in HNC patients. We previously reported on the beneficial short-term effects of the NUCAI on depressive symptoms and HNC-related physical symptoms in HNC patients 1 year after the completion of cancer treatment (van der Meulen et al, 2013). In this article, we report on the effect of the NUCAI on HRQoL, as secondary outcome of the trial, and depressive symptoms up to 2 years after cancer treatment. We hypothesised that the NUCAI would improve HRQoL and depressive symptoms in HNC patients 1–2 years after cancer treatment.

Patients and methods

Sample, ethical considerations and randomisation

Patients were enrolled by a researcher (MO) between January 2005 and September 2007 from the outpatient oral maxillofacial and the otorhinolaryngology clinics of a Dutch university hospital before the start of cancer treatment. Inclusion criteria were primary diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx, treatment with curative intent, ability to complete questionnaires in Dutch and ability to participate in the intervention. Patients were excluded if they had a previous or concomitant malignancy and/or were being treated for depression, diagnosed according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), as stated in their medical record.

According to the Zelen design, patients received general information about the goal of the study and that they would be randomised to one of two groups. They were also given written assurance that the post-cancer care provided by the HNC specialist would be the same in both groups. They were not given specific information about the intervention.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht and is registered under number ISRCTN06768231. After informed consent and the completion of cancer treatment, participants were randomised to the intervention or control group, using a web-based computer programme with an open block procedure stratified for sex and tumour stage. All researchers were blinded to the block sizes. For the duration of the study, participants were not informed which treatment they received.

Care as usual

Care as usual was provided bimonthly by HNC specialists and was primarily aimed at the treatment of complications and the detection of recurrences or second primary tumours. During the 10-minute medical follow-up visit, patients were examined, their physical history was reviewed, and ancillary tests were arranged as necessary. If the patient had psychosocial problems, the HNC specialist could refer the patient to psychological aftercare.

Intervention

The NUCAI aims to help patients manage the physical, psychological and social consequences of their disease and its treatment by giving advice, emotional support, education and behavioural training. The intervention is problem-focused and patient-driven, and was provided by trained nurses. Patients received a maximum of six counselling sessions of 45–60 min every 2 months over a period of 1 year, starting 6 weeks after the completion of cancer treatment. The counselling session was always combined with the patient's bimonthly medical check-up at the outpatient clinic.

The NUCAI can be divided into six components, which are:

Evaluating current mental status with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

Before each counselling session, the patients completed the HADS (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983; Spinhoven et al, 1997) at home. Nurses used the HADS score to screen for anxiety and/or depressive symptoms (cutoff >10 points) and to gain insight into the psychological status of the patient. Moreover, discussion of the results of the HADS often made it easier for patients to talk about their problems. The nurse screened the patient's history for the presence of psychosocial morbidity; this information was used to guide counselling.

Discussing current problems

The session started with a discussion of current problems and topics raised by the patient. Patients were then systematically asked about physical problems related to HNC, such as mastication, swallowing, shoulder function, sense of taste or smell, breathing, restrictions in speech, pain and fatigue.

Discussing life domains

Then patients were systematically asked about their functioning in six relevant life domains, namely, home situation, (resuming) work, household and leisure activities, mood and emotional distress, partner relation and intimacy, family and social life.

Providing the AFTER intervention

If indicated, the Adjustment to Fear, Threat or Expectation of Recurrence (AFTER) (Humphris and Ozakinci, 2008) intervention was carried out. This cognitive behavioural intervention, which is based on Leventhals' self-regulation model (Leventhal et al, 2005), was designed to reduce irrational thoughts and to help patients with orofacial cancer to handle excessive fear of recurrence and psychological distress. The AFTER intervention consists of four components, namely, expressing fear of recurrence, identifying beliefs about sensations and their interpretation as recurrence, evaluating the function of self-examination and reducing excessive checking behaviour, and relaxation.

Providing general medical assistance and advice

When indicated, the nurse gave information and advice, provided minor medical and/or behavioural treatment, and offered support in accordance with the Dutch oncological nursing guidelines (National Oncological Nursing Guidelines, 2000), the cancer clinical practice guidelines of the Dutch Association of Comprehensive Cancer (Oncoline; accessed, 2004), and the guidelines of the Nurse Intervention Classification (McCloskey and Bulechek, 2004).

Referring patients to psychological aftercare

If necessary, patients were referred to a psychiatrist or other doctor, a healthcare professional specialised in psychosocial problems (e.g., psychologist or social worker), or a relevant patient programme (e.g., oncological rehabilitation or patient support groups).

A manual was developed to assist the nurses in structuring the counselling sessions, discussing problems and choosing the appropriate nursing interventions. In addition, the nurses kept a treatment file for each of their patients, in which they recorded the content of the session. The following topics were given to structure the record: home situation, physical functioning, social functioning, mental functioning and nursing interventions.

Trained nurses

Three experienced oncology nurses were selected from the oral maxillofacial and the otorhinolaryngology department of a Dutch university hospital. Before the start of the study, the nurses were intensively trained to deliver the intervention. During the intervention period, sessions were evaluated with the nurses to monitor the quality of the intervention. More details about training can be found elsewhere (van der Meulen et al, 2013). The nurses continued to work on the ward as normal and received compensation for their additional duties, based on their normal salary.

Measures

Participants completed seven questionnaires at home, namely, at baseline, that is, before the start of cancer treatment, and at 3, 6, 9, 12 (i.e., completion of NUCAI), 18 and 24 months after completion of cancer treatment. Endpoints of interest were those recorded at 12 and 24 months after completion of cancer treatment. Measurements performed during the intervention phase were taken to gain insight into the pattern of change in HRQoL and depressive symptoms.

HRQoL was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0 (Aaronson et al, 1993) and the head and neck module QLQ H&N35 (Bjordal et al, 2000). Both are widely used and have good psychometric properties in HNC patients (Bjordal et al, 2000; Singer et al, 2012). A range of 0–100 is used and a difference of 10 points is considered to be clinically significant (Osoba et al, 2005). Depressive symptoms were measured with the CES-D (Radloff, 1977). This 20-item self-report questionnaire gives a total score ranging from 0 to 60. A high score reflects a high level of depression. The CES-D has shown good psychometric properties in Dutch HNC patients (de Leeuw et al, 2000a). In addition, information was collected about age, sex, education level and social status by means of self-report questionnaires. Information about treatment, tumour type and stage was obtained from medical records. All outcome data were collected by an independent researcher.

Statistics

The sample size was based on the prevalence of patients with raised levels of depressive symptoms (CES-D⩾12) established in previous analyses (van der Meulen et al, 2013). Power analysis for ANOVA procedures showed that, assuming an effect size of 0.32 with a two-sided test, a sample size of 45 patients with raised levels of depressive symptoms in each arm would suffice (power=80%, alpha=0.05). Data from our previous studies (de Graeff et al, 1999; de Leeuw et al, 2000b) showed that 56% of patients had a CES-D score of ⩾12 before cancer treatment. Therefore, a minimum of 160 HNC patients would be needed and 205 were enrolled to allow for study dropout.

Analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle (all patients with data at baseline and at least one follow-up measurement were included in analyses) and were performed using a linear mixed model approach. In these analyses, missing data were replaced by observed data, using maximum likelihood estimations (Twisk, 2003). Two-sided significant tests were used (α<0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 2.10.0 (www.r-project.org).

Results

Patients

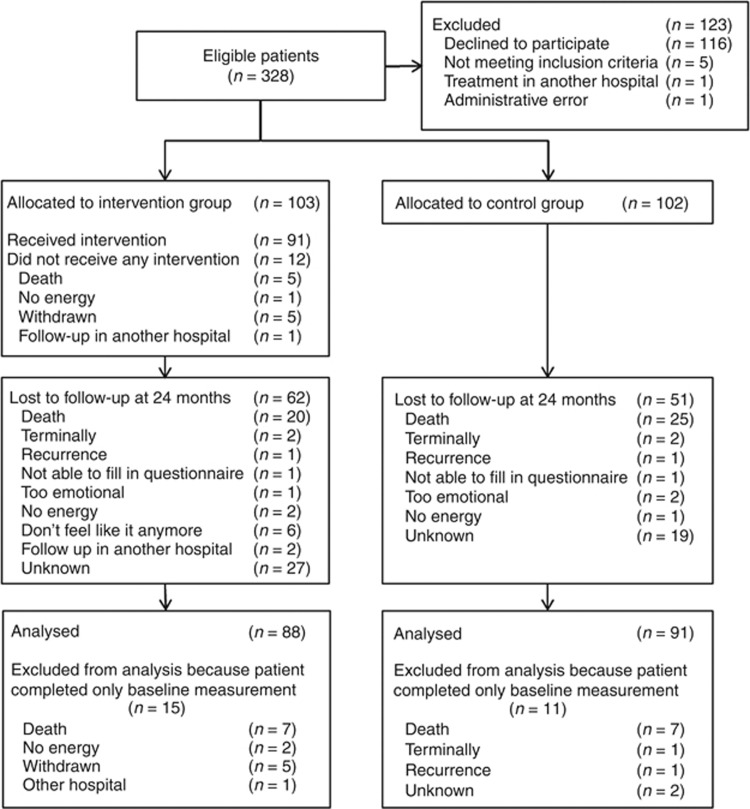

Of 328 eligible patients, 205 (62.5%) participated. Reasons for non-participation are shown in Figure 1. In total, 103 patients were randomised to the intervention group and 102 patients to the control group. At baseline, the intervention and control groups were comparable (P>0.05) in terms of demographic variables and clinical characteristics (Table 1). At 24 months after the completion of cancer treatment, 113 (50%) patients were lost to follow-up (intervention n=62; control n=51), 49 (43%) of whom had died or were terminally ill.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline by study arma.

| Intervention group (N=88) | Control group (N=91) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Age | ||

| Years (mean (s.d.)) |

60.1 (10) |

60.7 (10) |

|

Sex (no. (%)) | ||

| Male | 62 (70) | 64 (70) |

| Female |

26 (30) |

27 (30) |

|

Educational level (no. (%)) | ||

| Low | 37 (42) | 37 (41) |

| Middle | 32 (36) | 41 (45) |

| High |

19 (22) |

13 (14) |

|

Social status (no. (%)) | ||

| Married/living together | 63 (71.6) | 67 (74) |

| Single |

25 (28.4) |

24 (26) |

|

Working status (no. (%)) | ||

| Employed | 31 (35) | 34 (37) |

| Not employed | 29 (33) | 34 (37) |

| Retired | 19 (22) | 21 (23) |

| Unknown |

9 (10) |

2 (2) |

|

Type of cancer (no. (%)) | ||

| Larynx | 20 (23) | 22 (24) |

| Oral cavity | 41 (47) | 44 (19) |

| Oropharynx | 16 (18) | 17 (48) |

| Hypopharynx | 11 (13) | 7 (8) |

| Unknown primary |

— |

1 (1) |

|

Tumour stageb

(no. (%)) | ||

| I–II | 51 (58) | 54 (59) |

| III–IV | 37 (42) | 36 (40) |

| Unknown |

— |

1 (1) |

|

Type of treatment (no. (%)) | ||

| Surgery | 22 (25) | 29 (32) |

| Radiotherapy | 25 (28) | 24 (26) |

| RT/CH | 12 (14) | 12 (13) |

| Combination |

29 (33) |

26 (29) |

|

Coping style (mean (s.d.)) | ||

| Task-oriented | 18 (6) | 17 (5) |

| Emotion-oriented | 12 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Avoidance | 12 (5) | 12 (3) |

Abbreviations: CH=chemotherapy; RT=radiation therapy; s.d.=standard deviation.

Data is given of participants who completed a minimum of two measurements (n=179).

Tumour stage according to the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours.

Patients who were lost to follow-up had a significantly higher TNM status (P=0.03) and lower QoL (P=0.05) at baseline than patients who had completed the study. No differences were found in sociodemographic, clinical, global QoL or depressive symptoms between patients lost to follow-up in the intervention and control groups (see Table 2).

Table 2. Demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline for patients lost to follow-up by study arma.

| Patients lost to follow-up in the intervention group (N=62) | Patients lost to follow-up in the control group (N=51) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age | |||

| Years (mean (s.d.)) |

61 (11) |

62 (10) |

0.87 |

|

Sex (no. (%)) | |||

| Male | 47 (76) | 36 (71) | |

| Female |

15 (24) |

15 (29) |

0.54 |

|

Educational level (no. (%)) | |||

| Low | 20 (32) | 16 (31) | |

| Middle | 28 (45) | 27 (53) | |

| High |

14 (23) |

8 (16) |

0.66 |

|

Social status (no. (%)) | |||

| Married/living together | 46 (74) | 36 (71) | |

| Single | 15 (24) | 15 (29) | |

| Unknown |

1 (2) |

— |

0.64 |

|

Working status (no. (%)) | |||

| Employed | 22 (36) | 13 (26) | |

| Not employed | 20 (32) | 22 (43) | |

| Retired | 14 (23) | 12 (24) | |

| Unknown |

6 (10) |

4 (8) |

0.69 |

|

Type of cancer (no. (%)) | |||

| Larynx | 14 (23) | 10 (20) | |

| Oral cavity | 28 (45) | 25 (49) | |

| Oropharynx | 10 (16) | 12 (24) | |

| Hypopharynx | 10 (16) | 3 (6) | |

| Unknown primary |

— |

1 (2) |

0.90 |

|

Tumour stagea

(no. (%)) | |||

| I–II | 33 (53) | 23 (45) | |

| III-IV |

29 (47) |

28 (55) |

0.39 |

|

Type of treatment (no. (%)) | |||

| Surgery | 14 (23) | 12 (24) | |

| Radiotherapy | 17 (27) | 12 (24) | |

| RT/CH | 10 (16) | 10 (20) | |

| Combination |

21 (34) |

17 (33) |

0.95 |

|

Coping style (mean (s.d.)) | |||

| Task-oriented | 18 (5) | 19 (5) | 0.35 |

| Emotion-oriented | 12 (4) | 13 (5) | 0.54 |

| Avoidance |

12 (4) |

12 (5) |

0.34 |

| Global QoL (mean (s.d.)) |

66 (22) |

60 (25) |

0.14 |

| Depressive symptoms (mean (s.d.)) | 12 (8) | 13 (9) | 0.60 |

Abbreviations: CH=chemotherapy; RT=radiation therapy; s.d.=standard deviation.

Tumour stage according to the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours.

Compliance

Of the 103 patients allocated to the intervention group, 12 (11.7%) did not attend any of the counselling sessions. Reasons for non-attendance are presented in Figure 1. Of the participants who completed the assessment at 12 months, 49% had received ⩾5 counselling sessions; at 18 months the proportion was 91% and at 24 months 95%. Two patients, one at 18 and one at 24 months, received an additional seventh counselling session. The counselling sessions were sometimes delayed because it was not always possible for physicians to hold follow-up visits at bimonthly intervals, and the NUCAI was always given in combination with these appointments.

Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms

The longitudinal results of the EORTC-C30, EORTC-H&N35 and depressive symptoms are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Table 3 shows the descriptive mean scores and standard error for patients by randomisation status. Table 4 presents the between-group differences following the intention-to-treat method.

Table 3. Descriptives of health-related quality of life, head and neck cancer-specific health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms over the 24-month study perioda.

| BL | 12M | 18M | 24M | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (s.e.) | mean (s.e.) | mean (s.e.) | mean (s.e.) | |

|

EORTC QLQ-C30b | ||||

| Global QoL | I 67.3 (2.3) | 73.6 (2.4) | 77.8 (2.7) | 77.5 (2.8) |

| |

C 66.2 (2.3) |

68.1 (2.4) |

71.1 (2.5) |

74.5 (2.6) |

| Physical functioning | I 84.4 (2.2) | 81.5 (2.2) | 83.2 (2.4) | 82.4 (2.5) |

| |

C 87.0 (2.1) |

79.1 (2.2) |

81.3 (2.3) |

80.5 (2.4) |

| Role functioning | I 76.3 (3.0) | 79.4 (3.2) | 83.2 (3.6) | 82.8 (3.8) |

| |

C 77.7 (3.0) |

78.6 (3.2) |

73.2 (3.3) |

77.8 (3.5) |

| Emotional functioning | I 64.8 (2.4) | 82.8 (2.5) | 85.6 (2.8) | 84.9 (3.0) |

| |

C 66.9 (2.4) |

75.0 (2.5) |

78.3 (2.6) |

77.2 (2.8) |

| Cognitive functioning | I 83.9 (2.2) | 83.1 (2.4) | 87.7 (2.6) | 84.7 (2.8) |

| |

C 84.2 (2.2) |

82.8 (2.3) |

85.1 (2.4) |

83.8 (2.6) |

| Social functioning | I 83.1 (2.5) | 87.1 (2.7) | 88.9 (3.1) | 88.5 (3.2) |

| |

C 83.1 (2.5) |

80.0 (2.6) |

85.0 (2.8) |

85.1 (3.0) |

| Fatigue | I 27.9 (2.7) | 25.7 (2.9) | 20.4 (3.2) | 19.9 (3.4) |

| |

C 25.9 (2.7) |

29.9 (2.8) |

24.8 (3.0) |

27.1 (3.1) |

| Nausea and vomiting | I 3.4 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.8) |

| |

C 4.2 (1.3) |

6.4 (1.4) |

4.1 (1.5) |

4.9 (1.7) |

| Pain | I 27.8 (2.8) | 14.0 (3.0) | 10.0 (3.4) | 11.4 (3.6) |

| |

C 26.4 (2.7) |

22.3 (2.9) |

21.1 (3.1) |

17.8 (3.3) |

| Dyspnoea | I 11.7 (2.7) | 14.6 (2.8) | 13.1 ( 3.1) | 13.2 (3.3) |

| |

C 12.8 (2.7) |

17.0 (2.8) |

15.3 (2.9) |

18.5 (3.1) |

| Insomnia | I 28.4 (3.1) | 19.2 (3.3) | 18.5 (3.9) | 12.7 (4.1) |

| |

C 28.2 (3.1) |

19.5 (3.3) |

21.4 (3.5) |

19.6 (3.8) |

| Appetite loss | I 11.7 (2.8) | 13.1 (2.9) | 10.1 (3.4) | 6.4 (3.6) |

| |

C 19.0 (2.7) |

17.8 (2.9) |

15.8 (3.1) |

14.2 (3.3) |

| Constipation | I 7.6 (2.0) | 7.9 (2.1) | 8.1 (2.4) | 6.4 (2.6) |

| |

C 5.5 (1.9) |

8.0 (2.1) |

8.6 (2.2) |

8.4 (2.4) |

| Diarrhoea | I 3.0 (1.9) | 12.6 (2.1) | 12.3 (2.5) | 12.4 (2.7) |

| |

C 4.4 (1.9) |

15.0 (2.1) |

12.5 (2.3) |

16.4 (2.5) |

| Financial difficulties | I 9.1 (2.5) | 11.5 (2.6) | 8.5 (2.9) | 11.1 (3.1) |

| |

C 9.6 (2.5) |

10.9 (2.6) |

9.9 (2.7) |

11.2 (2.8) |

|

EORTC QLQ-H&N35b | ||||

| Pain | I 36.0 (2.4) | 17.3 (2.5) | 15.5 (2.9) | 15.1 (3.1) |

| |

C 31.1 (2.3) |

22.3 (2.5) |

19.0 (2.6) |

15.6 (2.8) |

| Swallowing | I 22.7 (2.5) | 18.8 (2.7) | 18.3 (3.0) | 17.2 (3.2) |

| |

C 18.1 (2.5) |

21.3 (2.6) |

21.2 (2.8) |

15.7 (2.9) |

| Senses | I 9.8 (2.6) | 18.9 (2.7) | 18.1 (3.0) | 24.0 (3.2) |

| |

C 7.7 (2.5) |

20.4 (2.7) |

20.9 (2.8) |

19.4 (3.0) |

| Speech | I 23.0 (2.6) | 18.2 (2.7) | 17.0 (3.1) | 16.2 (3.3) |

| |

C 23.4 (2.6) |

21.3 (2.7) |

19.8 (2.8) |

18.8 (3.0) |

| Social eating | I 9.8 (2.8) | 18.9 (2.9) | 18.1 (3.2) | 24.0 (3.4) |

| |

C 7.7 (2.7) |

20.4 (2.9) |

20.9 (3.0) |

19.4 (3.1) |

| Social contact | I 7.6 (1.8) | 8.0 (1.9) | 8.1 (2.1) | 7.7 (2.2) |

| |

C 6.2 (1.8) |

14.2 (1.9) |

11.2 (2.0) |

10.6 (2.1) |

| Sexuality | I 27.1 (3.8) | 27.2 (4.0) | 24.3 (4.5) | 22.3 (4.7) |

| |

C 25.8 (3.7) |

32.0 (3.9) |

29.8 (4.1) |

26.0 (4.3) |

| Teeth | I 23.0 (3.3) | 20.4 (3.6) | 18.5 (4.1) | 17.5 (4.3) |

| |

C 23.8 (3.2) |

25.7 (3.5) |

21.4 (3.7) |

15.6 (4.0) |

| Opening mouth | I 19.0 (3.2) | 15.1 (3.4) | 8.8 (3.9) | 13.0 (4.1) |

| |

C 17.6 (3.1) |

28.2 (3.4) |

24.3 (3.6) |

18.1 (3.8) |

| Dry mouth | I 16.3 (3.5) | 36.8 (3.7) | 35.8 (4.2) | 33.4 (4.5) |

| |

C 18.7 (3.5) |

38.6 (3.7) |

35.0 (3.9) |

32.8 (4.1) |

| Sticky saliva | I 19.5 (3.3) | 32.7 (3.5) | 28.6 (4.0) | 23.8 (4.3) |

| |

C 15.8 (3.3) |

34.4 (3.5) |

30.8 (3.7) |

26.5 (3.9) |

| Coughing | I 22.3 (3.0) | 27.4 (3.2) | 23.7 (3.6) | 23.7 (3.8) |

| |

C 25.3 (2.9) |

19.5 (3.1) |

22.9 (3.3) |

23.6 (3.5) |

| Felt ill | I 17.8 (2.6) | 9.0 (2.8) | 8.6 (3.3) | 7.3 (3.5) |

| |

C 18.7 (2.6) |

14.1 (2.8) |

15.7 (3.0) |

11.2 (3.2) |

|

CES-D | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | I 12.9 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.1) | 9.5 (1.2) | 10.6 (1.3) |

| C 12.9 (1.0) | 14.1 (1.1) | 13.2 (1.1) | 13.2 (1.2) | |

Abbreviations: BL=baseline, C=control group; I=intervention group; M=months; SE=standard error.

Data is given following the intention-to-treat principles (n=179: intervention group n=88; control group n=91).

A high score for a functional scale/global QoL represents a high level of functioning/global QoL, whereas a high score for a symptom scale represents a high level of problems. Symptom scales are presented below the dotted line.

Table 4. EORTC QLQ C30, H&N35 and depressive symptoms—between-group differencesa , b.

| 12M | 18M | 24M | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

EORTC QLQ-C30c | |||

| Global QoL | 5.5 (−0.5–11.4) | 6.7 (0.1–13.3)d | 3.0 (−4.0–10.0) |

| Physical functioning | 4.9 (0.6–9.3)d | 4.4 (−0.4–9.3) | 4.5 (−0.6–9.7) |

| Role functioning | 5.2 (−3.3–13.7) | 11.3 (1.9–20.7)d | 6.3 (−3.7–16.3) |

| Emotional functioning | 9.9 (3.6–16.2)d | 9.4 (2.4–16.4)d | 9.7 (2.3–17.1)d |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.6 (−5.3–6.5) | 2.9 (−3.6–9.4) | 1.2 (−5.7–8.2) |

| Social functioning | 7.1 (−0.1–14.3) | 3.9 (−4.1–11.9) | 3.3 (−5.2–11.9) |

| Fatigue | −6.5 (−13.6–0.6) | −6.7 (−14.5–1.1) | −9.4 (−17.8–−1.1)d |

| Nausea or vomiting | 4.4 (−0.4–9.1) | 1.0 (−4.2–6.3) | 2.8 (−2.7–8.4) |

| Pain | −8.9 (−16.9–−1.0)d | −12.6 (−21.4–−3.8)d | −7.9 (−17.2–1.4) |

| Dyspnoea | −7.8 (−1.3–5.2) | −1.1 (−8.3–6.1) | −4.2 (−11.9–3.4) |

| Insomnia | −0.4 (−9.9–9.0) | −3.2 (−13.7–7.3) | −7.1 (−18.3–4.1) |

| Appetite loss | 2.6 (−5.7–10.9) | 1.7 (−7.5–10.9) | −0.5 (−10.3–9.2) |

| Constipation | −2.1 (−8.2–3.9) | −2.6 (−9.3–4.1) | −4.1 (−11.2–2.9) |

| Diarrhoea | −1.0 (−8.2–6.1) | 1.2 (−6.7–9.0) | −2.6 (−11.0–5.7) |

| Financial difficulties |

1.1 (−5.2–7.5) |

−1.0 (−8.0–6.0) |

0.4 (−7.1–7.8) |

|

EORTC QLQ-H&N35c | |||

| Pain | −9.9 (−17.0–−2.9)d | −8.3 (−16.1–−0.5)d | −5.4 (−13.7–2.9) |

| Swallowing | −8.1 (−14.8–−1.3)d | −7.5 (−14.9–−0.0)d | −3.1 (−11.0–4.8) |

| Senses | −3.7 (−10.6–3.1) | −4.9 (−12.5–2.7) | 2.4 (−5.6–10.5) |

| Speech | −2.7 (−9.9–4.5) | −2.3 (−10.3–5.6) | −2.2 (−10.6–6.2) |

| Social eating | −5.6 (−12.4–1.2) | −3.6 (11.1–4.0) | −0.5 ( −8.5–7.5) |

| Social contact | −7.6 (−12.4–−2.9)d | −4.5 (−9.8–0.7) | −4.3 (−9.9–1.3) |

| Sexuality | −6.0 (−15.9–3.9) | −6.8 (−17.7–4.2) | −4.9 (−16.5–6.6) |

| Teeth | −4.5 (−14.7–5.8) | −2.1 (−13.4–9.2) | 2.8 (−9.2–14.8) |

| Opening mouth | −14.6 (−24.0–−5.2)d | −17.0 (−27.4–−6.6)d | −6.6 (−17.6–4.5) |

| Dry mouth | 0.6 (−9.2–10.4) | 3.1 (−7.7–14.0) | 3.0 (−8.5–14.6) |

| Sticky saliva | −5.4 (−14.9–4.1) | −6.0 (−16.5–4.6) | −6.5 (−17.7–4.7) |

| Coughing | 10.9 (2.2–19.5)d | 3.8 (−5.8–13.4) | 3.0 (−7.2–13.1) |

| Felt ill |

−4.2 (−12.6–4.2) |

−6.2 (−15.5–3.1) |

−2.9 (−12.9–7.0) |

|

CES-Dc | |||

| Depressive symptoms | −2.8 (−5.2–−0.3)d | −3.7 (−6.4–−1.0)d | −2.6 (−5.5–0.2) |

Bold values indicate significant findings.

Data are mean differences with a confidence interval (CI)of 95% with baseline score as reference.

Data is given following the intention-to-treat principles (n=179: intervention group n=88; control group n=91).

A high score for a functional scale/global QoL represents a high level of functioning/global QoL, whereas a high score for a symptom scale represents a high level of problems. Symptom scales are presented below the dotted line.

Significant difference with a CI 95%.

QLQ C30

At 12 months after treatment completion, the intervention group had a significantly improved physical functioning (4.9, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.6–9.3) and emotional functioning (9.9, 95% CI: 3.6–16.2) and diminished pain (−9.9, 95% CI: −17.0 to −2.9) compared with the control group. At 18 months, significant differences were found for global QoL (6.7, 95% CI: 0.1–13.3), role functioning (11.3, 95% CI: 1.9–20.7), emotional functioning (9.4, 95% CI: 2.4–16.4) and pain (−12.6, 95% CI: −21.4 to −3.8). At 24 months, the emotional functioning of patients in the intervention group was still significantly better (9.7, 95% CI: 2.3–17.1) and they were significantly less fatigued (−9.4, 95% CI: −17.8 to −1.1) than the patients in the control group.

QLQ H&N35

At 12 months, the intervention group reported significantly fewer problems with pain (−9.9, 95% CI: −17.0 to −2.9), swallowing (−8.1, 95% CI: −14.8 to −1.3), social contact (−7.6, 95% CI: −12.4 to −2.9) and mouth opening (−14.6, 95% CI: −24.0 to −5.2) than the control group. However, the intervention group reported significantly more problems with coughing than the control group (10.9, 95% CI: 2.2–19.5). At 18 months, the beneficial effects of the NUCAI on pain (−8.3, 95% CI: −16.1 to −0.5), swallowing (−7.5, 95% CI: −14.9 to −0.0) and opening mouth (−17.0, 95% CI: −27.4 to −6.6) were still present, but at 24 months there were no between-group differences in any HNC-related symptom.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were significantly diminished at 12 months in the intervention group compared with the control group (−2.8, 95% CI: −5.2 to −0.3) and this improvement was still seen at 18 months (−3.7, 95% CI: −6.4 to −1.0). At 24 months, depressive symptoms were still lower, although non-significantly, in the intervention group (−2.6, CI: −5.5 to 0.2).

Discussion

General discussion

This RCT showed the effectiveness of a comprehensive 12-month nurse-led psychosocial intervention in improving HRQoL and depressive symptoms in HNC patients. Significant improvements were found in physical and emotional functioning, pain, swallowing, social contact, mouth opening and depressive symptoms 12 months after the completion of cancer treatment in the intervention group. At 18 months, patients in the intervention group reported improvements in global QoL, role and emotional functioning, pain, swallowing, mouth opening and depressive symptoms. At 24 months emotional functioning and fatigue were better in the intervention group than in the control group. Most of the significant findings showed a substantial difference of almost, or more than, 10 points, which can be considered clinically relevant (Osoba et al, 2005).

The intervention did not have a significant effect on nausea and vomiting, or constipation and diarrhoea, possibly because few patients experienced these problems (scores <10 points). However, the intervention also did not have a significant effect on sexuality, dry mouth and sticky saliva, aspects that the patients did consider problematic. Two recently published Cochrane reviews of RTCs on interventions for dry mouth (Furness et al, 2011, 2013) showed that saliva substitute sprays are beneficial and that a gel-releasing device worn in the mouth and a mouth care system are potentially promising treatments (Furness et al, 2011). Acupuncture, as non-medical treatment, was not found to better than placebo for alleviating the problems of dry mouth and sticky saliva (Furness et al, 2013). Overall, the quality of the studies was rather poor and the studies provided insufficient evidence to guide clinical care (Furness et al, 2011). One small pilot study with institutionalised elderly individuals described lemon-lime sorbet to be effective against dry mouth (Crogan, 2011). Concerning sexuality problems, Kagan (2009) emphasised the complexity of problems with sexuality in older cancer patients and the complexity of tailored interventions. They recommended integrating standards of practice for intimacy and sexuality as advised for younger adults in any intervention for older individuals, together with information about issues unique to older people (Kagan, 2009). As there is little available information, future studies should focus on effective strategies to combat these specific problems in HNC patients. Findings can then be integrated into the NUCAI, to improve HRQoL in all domains.

To our knowledge, no RCTs have been published that evaluated interventions to increase HRQoL in HNC patients. Instead, often quasi-experimental designs were used (Allison et al, 2004; de Leeuw et al, 2013) and/or small study samples (Allison et al, 2004; Semple et al, 2009). The results of a quasi-experimental study (de Leeuw et al, 2013) (n=160), using an intervention comparable to the NUCAI, showed that most HRQoL scores improved in the intervention group compared with the control group 6 and 12 months after treatment. Another small study (Semple et al, 2009) (n=54) reported improvements in social functioning and QoL scores compared with control 3 months after a problem-focused psychosocial intervention consisting of 2–6 sessions led by a nurse specialist at the patient's home. A feasibility study (n=50) showed a psycho-educational intervention to have some beneficial effects on HRQoL and depressive symptoms (Allison et al, 2004). Our results, coming from a study with a robust design and long follow-up are in line with these findings. A recently published Cochrane review (Semple et al, 2013) included seven RCTs or quasi-RCTs (which also included unpublished results) that evaluated QoL and/or psychological distress. The review concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychosocial interventions for HNC patients (the result of the current study were not included in the meta-analyses). Semple et al, 2013 mentioned numerous difficulties in reviewing the studies, such as the small number of studies, low power, and heterogeneous interventions and outcome measures. Overall, the results of our and another study (Sherman and Simonton, 2010) suggest that interventions that are structured, theoretically based and skill-focused are promising in terms of improving HRQoL and decreasing depressive symptoms (Sherman and Simonton, 2010). Multicentre trials are needed to ensure sufficient numbers of patients (Cousins et al, 2013; Semple et al, 2013).

The involvement of nurses in patient aftercare may necessitate a change in traditional study designs. Although we did not explicitly investigate the cooperation between doctors and nurses, it went well, but it should be remembered that the NUCAI was additional to standard medical follow-up, unlike other nurse-led interventions (e.g. Wells et al, 2008). A small survey conducted by Urquhart et al (2011) showed that 67% of interviewed clinicians were against nurse-led clinics, at least in England. This means that necessary attention should be paid to the cooperation between clinicians and nurses, and to the role of a nurse-led intervention in the aftercare of HNC patients.

Limitations and strengths

Some difficulties arose during the intervention, such as the delay in counselling sessions with the result that 51% of the patients had received four sessions or less at 12 months. Outpatient clinics are a busy and challenging environment, and it is therefore of great importance that the intervention is integrated into the organisation of the clinic and that counselling sessions are given in a friendly, quiet and accessible room near to where the doctors are working. The study had some uncontrollable variables such as the patient or doctor being ill or the patient forgetting his/her appointment.

An important strength of the study is the educational training given to the nurses before the start of the study and their supervision during the study. Nurses traditionally have a direct approach to solving problems as they are mentioned or occur, but the training and supervision enabled the nurses to listen more carefully and to encourage the patient to talk about his/her problems. It is important that the nurses who give the intervention have extensive experience in the care for HNC patients, have good communication skills, are self-reliant and are able to work closely with other professionals, as was the case for the nurses who led the intervention in this study.

Most participants had early, stage I–II cancer, which possibly reflects the ability of general practitioners to recognise the disease and to refer patients to an HNC specialist in a timely fashion.

However, the study population was generally comparable to that of our previous study (de Graeff et al, 1999), which strengthens the extent to which findings can be generalised to the Dutch population of HNC patients. Although we performed a number of analyses, which increases the chance of false-positive findings, we think it is unlikely that the beneficial effects of NUCAI on HRQoL were due entirely to chance, given the pattern of findings. Compared with other, more intensive, interventions (Sharma et al, 2008; Kangas et al, 2013), we consider the NUCAI to be a relatively low-cost intervention, given its nurse-led approach and the relatively few sessions involved. Moreover, findings suggest that it can be implemented in the follow-up care for HNC patients, although the overall costs and feasibility of the intervention remain to be investigated. Overall, the study design, an RCT with a long follow-up, strengthens the findings of the study, especially because of the lack of other RCTs of interventions to improve HRQoL in HNC patients.

Conclusion

This RCT showed that the nurse-led NUCAI is feasible and effective in HNC patients and improved physical and emotional functioning, pain, swallowing, social contact, mouth opening and depressive symptoms 12 months after the completion of cancer treatment. Improvements in global QoL, role and emotional functioning, pain, swallowing, mouth opening and depressive symptoms were seen at 18 months, and improvements in emotional functioning and fatigue at 24 months. The NUCAI is a valid intervention, thanks to its structured, theory-based, problem-focused, and nurse-led nature, and appears to be a promising to implement in daily practice.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded through a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society. The trial is registered under number ISRCTN06768231.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, JCJMd Haes, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PJ, Edgar L, Nicolau B, Archer J, Black M, Hier M. Results of a feasibility study for a psycho-educational intervention in head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:482–485. doi: 10.1002/pon.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [DSM-IV-TR] American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, Hammerlid E, van Pottelsberghe C, Curran D, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Maher EJ, Meyza JW, Brédart A, Söderholm AL, Arraras JJ, Feine JS, Abendstein H, Morton RP, Pignon T, Huguenin P, Bottomly A, Kaasa S. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1796–1807. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins N, MacAulay F, Lang H, MacGillivray S, Wells M. A systematic review of interventions for eating and drinking problems following treatment for head and neck cancer suggests a need to look beyond swallowing and trismus. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crogan N. Managing xerostomia in nursing homes: pilot testing of the Sorbet Increases Salivation intervention. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graeff A, de Leeuw RJ, Ros WJ, Hordijk GJ, Battermann JJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JA. A prospective study on quality of life of laryngeal cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Head Neck. 1999;21:291–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199907)21:4<291::aid-hed1>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw JR, de Graeff A, Ros WJ, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JA. Negative and positive influences of social support on depression in patients with head and neck cancer: a prospective study. Psychooncology. 2000;9:20–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<20::aid-pon425>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw JR, de Graeff A, Ros WJ, Blijham GH, Hordijk GJ, Winnubst JA. Prediction of depressive symptomatology after treatment of head and neck cancer: the influence of pre-treatment physical and depressive symptoms, coping, and social support. Head Neck. 2000;22:799–807. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<799::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw J, Prins J, Teerenstra S, Merkx MAW, Marres HAM, van Achterberg T. Nurse-led follow-up care for head and neck cancer patients: a quasi-experimental prospective trial. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:537–547. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Association of Comprehensive Cancer Centers. Oncoline Cancer Clinical Practice Guidelines. Available at http://www.oncoline.nl/index.php Accessed (2004).

- Eades M, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Rehabilitation: long-term physical and functional changes following treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness S, Bryan G, McMillan R, Birchenough S, Worthington H. Interventions for the management of dry mouth: non-pharmacological interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD009603–CD009603. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009603.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness S, Worthington H, Bryan G, Birchenough S, McMillan R.2011Interventions for the management of dry mouth: topical therapies Cochrane Database Syst Revdoi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008934.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hammerlid E, Silander E, Hornestam L, Sullivan M. Health-related quality of life three years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer—a longitudinal study. Head Neck. 2001;23:113–125. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<113::aid-hed1006>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Tian J, Zhang W, Pan J, Chen Y, Ma L, Lv W.2013Patient characteristics as indicators for poor quality of life after radiotherapy in advanced nasopharyngeal cancer Head Neck Oncol 51723466795 [Google Scholar]

- Humphris G, Ozakinci G. The AFTER intervention: a structured psychological approach to reduce fears of recurrence in patients with head and neck cancer. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13:223–230. doi: 10.1348/135910708X283751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan SH. The influence of nursing in head and neck cancer management. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:248–253. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328329b819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas M, Milross C, Taylor A, Bryant R. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a brief early intervention for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depressive symptoms in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1665–1673. doi: 10.1002/pon.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Halm E, Horowitz C, Leventhal EA, Ozakinci G.2005Living with chronic illness: a contextualized, self-regulation approachIn: Sutton S, Johnston M, Baum A (eds).The Sage Handbook of Health Psychology Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; 197–240. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey J, Bulechek GM. Elsevier—Health Sciences Division; 2004. Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehanna HM, Morton RP. Deterioration in quality-of-life of late (10-year) survivors of head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Oncological Nursing Guidelines (Vereniging van Integrale Kanker Centra (VIKC): Landelijke Oncologische Verpleegkundige Richtlijnen) Leens. Grafische Industrie De Marne: The Netherlands; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oskam IM, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Aaronson NK, Witte BI, de Bree R, Doornaert P, Langendijk JA, René Leemans C. Prospective evaluation of health-related quality of life in long-term oral and oropharyngeal cancer survivors and the perceived need for supportive care. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Bezjak A, Brundage M, Zee B, Tu D, Pater J. Analysis and interpretation of health-related quality-of-life data from clinical trials: basic approach of The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner J. Psychosocial care of patients with head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS.1977. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population.1385–401.

- Rogers SN, Ahad SA, Murphy AP. A structured review and theme analysis of papers published on ‘quality of life' in head and neck cancer: 2000–2005. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:843–868. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronis DL, Duffy SA, Fowler KE, Khan MJ, Terrell JE. Changes in quality of life over 1 year in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:241–248. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple C, Parahoo K, Norman A, McCaughan E, Humphris G, Mills M. Psychosocial interventions for patients with head and neck cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009441–CD009441. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009441.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple CJ, Dunwoody L, Kernohan WG, McCaughan E. Development and evaluation of a problem-focused psychosocial intervention for patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:379–388. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Nagarkar A, Jindal P, Kaur R, Gupta A. Personality changes and the role of counseling in the rehabilitation of patients with laryngeal cancer. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87:E5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Simonton S. Advances in quality of life research among head and neck cancer patients. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:208–215. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Arraras J, Chie W, Fisher S, Galalae R, Hammerlid E, Nicolatou Galitis O, Schmalz C, Verdonck-de Leeuw I, Gamper E, Keszte J, Hofmeister D. Performance of the EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients EORTC QLQ-H N35: a methodological review. Qual Life Res. 2012;22 (8:1927–1941. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27:363–370. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twisk JWR.2003Missing data in longitudinal studiesChapter 10: InApplied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A Practical Guide 202.Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart C, Hassanali HA, Kanatas AN, Mitchell DA, Ong TK. The role of the specialist nurse in the review of patients with head and neck cancer—is it time for a rethink of the review process. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen IC, May A, Ros WJG, Oosterom M, Hordijk G, Koole R, de Leeuw JRJ. One-year effect of a nurse-led psychosocial intervention on depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Oncologist. 2013;18:336–344. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Donnan PT, Sharp L, Ackland C, Fletcher J, Dewar JA. A study to evaluate nurse-led on-treatment review for patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:1428–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]