Abstract

Purpose

We investigated early postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis who had undergone radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 41 patients who underwent radical gastrectomy at the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (Hwasun-gun, Korea) between August 2004 and June 2009. There were few patients with Child-Pugh class B or C; therefore, we restricted patient selection to those with Child-Pugh class A.

Results

Postoperative complications were observed in 22 (53.7%) patients. The most common complications were ascites (46.3%), postoperative hemorrhage (22.0%) and wound infection (12.2%). Intra-abdominal abscess developed in one (2.4%) patient who had undergone open gastrectomy. Massive ascites occurred in 4 (9.8%) patients. Of the patients who underwent open gastrectomy, nine (21.9%) patients required blood transfusions as a result of postoperative hemorrhage. However, most of these patients had advanced gastric cancer. In contrast, most patients who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy had early stage gastric cancer, and when the confounding effect from the different stages between the two groups was corrected statistically, no statistically significant difference was found. There was also no significant difference between open and laparoscopic gastrectomy in the occurrence rate of other postoperative complications such as ascites, wound infection, and intra-abdominal abscess. No postoperative mortality occurred.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic gastrectomy is a feasible surgical procedure for patients with moderate hepatic dysfunction.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Liver cirrhosis, Gastrectomy

Introduction

Early diagnosis, radical operation, and advances in adjuvant therapy have substantially improved the prognosis of gastric cancer. However, gastric cancer remains one of the most common causes of cancer-related death in Korea.1 Liver cirrhosis (LC) is also a major health concern in Korea. It is the fourth most common cause of death. Contributing factors include hepatitis B and C and alcohol consumption.2 Therefore, clinicians experience any gastric cancer patient who accompanies LC.

Recent advances in perioperative care and surgical techniques have contributed to decreased morbidity and mortality rates associated with gastric cancer surgery, even after D2 lymph node (LN) dissection. Many researchers have demonstrated that D2 LN dissection in patients with Child-Pugh class A is feasible.3,4

Laparoscopic gastrectomy has been used to treat patients with early gastric cancer surgery for several years. Currently, surgeons are treating patients with advanced gastric cancer via laparoscopic gastrectomy. Many researchers have demonstrated that laparoscopic gastrectomy is safe and has many advantages compared with open gastrectomy.5-7 However, there are few studies that support treating patients via laparoscopic gastrectomy in patients with LC. This study examines postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with gastric cancer and LC who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients with LC who had undergone radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer at the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital in Huasun-gun, South Korea between August 2004 and June 2009.

Patients were diagnosed with LC via abdominal sonogram, liver biopsy, and clinical and intraoperative findings. The Child-Turcotte-Pugh and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores were used to determine LC severity. We limited our study to patients with Child-Pugh class A because there were few patients with Child-Pugh classes B and C. No patients had a history of abdominal surgery or other malignancies.

Ascites was defined as moderate when ascites of >500 ml per day passed through the drainage tube or if diuretic treatment was required as a result of abdominal distension. Ascites was defined as severe when ascites of >1,000 ml per day passed through the drainage tube or if paracentesis was required because of huge abdominal distension.

When clinical signs of bleeding were observed (i.e., hemoglobin levels <7 g/dl or hemoglobin changes of >2 g/dl), this was classified as postoperative hemorrhage and transfusion was performed.

LN dissection was scored according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines. D1+α was defined as limited LN dissection in which the perigastric LNs and LNs along the left gastric artery were removed. D1+β was defined as LN dissection that included D1+α dissection and LNs along the common hepatic artery and celiac axis. D2 dissection was defined as LN dissection that included 14v LN in the lower one-third of stomach cancer.

We used statistical analysis to correct confounding effects of the pathologic stage and extent of LN dissection between open and laparoscopic gastrectomy groups.

Patient characteristics were assessed, including age, sex, cause of cirrhosis, extent of gastric resection, tumor stage, and postoperative outcomes, including the extent of LN dissection, complications, and preoperative laboratory findings associated with postoperative complications.

SPSS Statistics ver. 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, Student's t-test, and Mann-Whitney test were used for comparisons. We used the logistic regression test to control expected confounding effects of other variables. All statistical tests were assumed to be statistically significant when P-value is <0.05.

Results

1. Patient characteristics

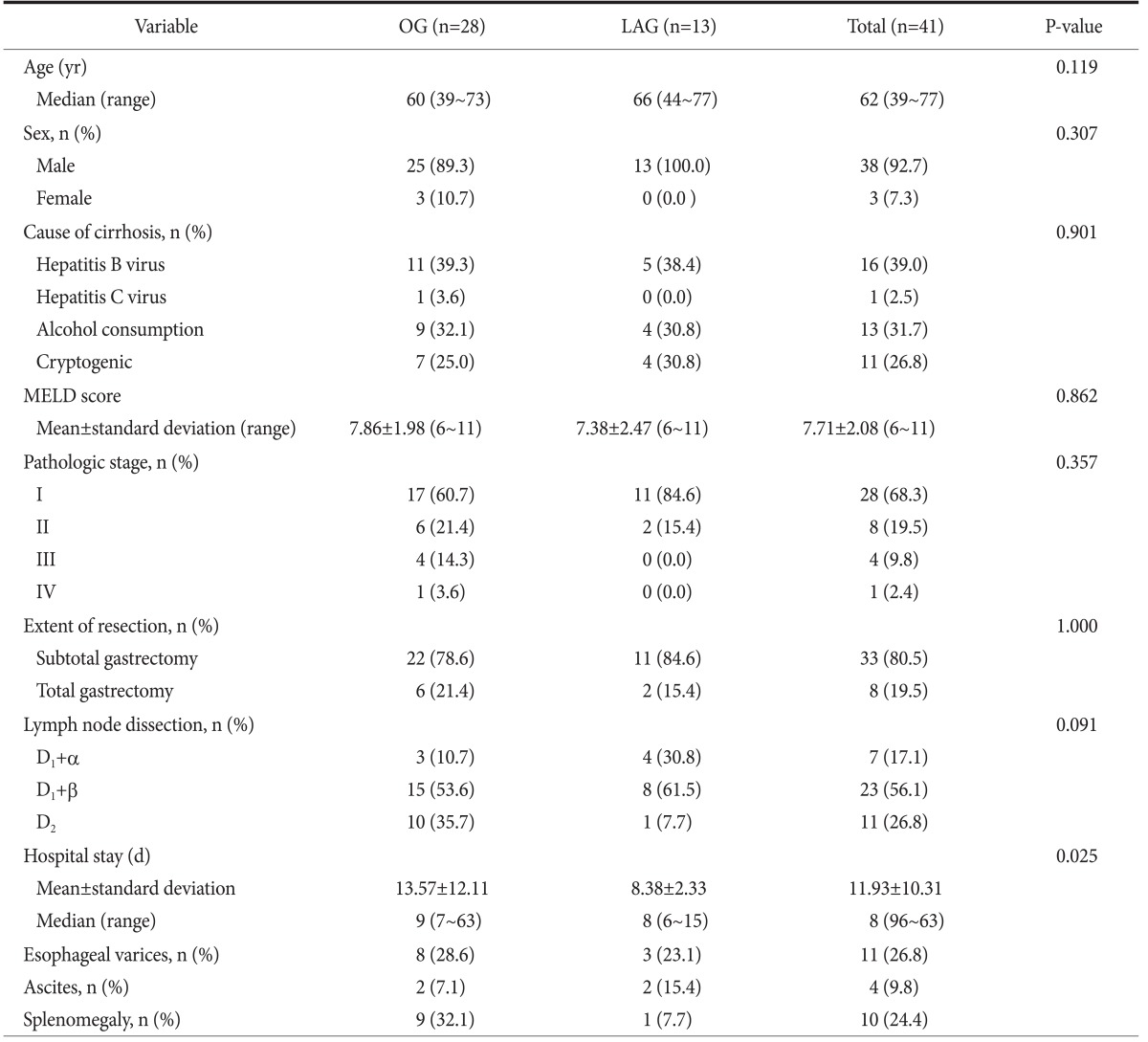

Forty-one patients with gastric cancer who underwent radical gastrectomy were enrolled in this study. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. There were 38 (92.7%) males and 3 (7.3%) females, and the median age was 62 years (range, 39 to 77 years). All patients were classified as Child-Pugh class A, and MELD scores ranged from 6 to 11.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

OG = open gastrectomy; LAG = laparoscopic gastrectomy; MELD = Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

Of the 41 patients assessed, 28 (68.3%) were classified as pathologic stage I. In general, the group that was treated via open gastrectomy had a more advanced pathologic stage and had greater LN dissection, particularly D2 dissection. Thirty-three (80.5%) patients underwent partial gastrectomy, and 8 (19.5%) patients underwent total gastrectomy.

Esophageal varices were identified preoperatively in 11 (26.8%) patients via endoscopy or computed tomography (CT). Preoperative ascites were detected in 4 (9.8%) patients via CT or operative findings. Splenomegaly was detected in 10 (24.4%) patients via preoperative CT.

2. Postoperative morbidity and mortality

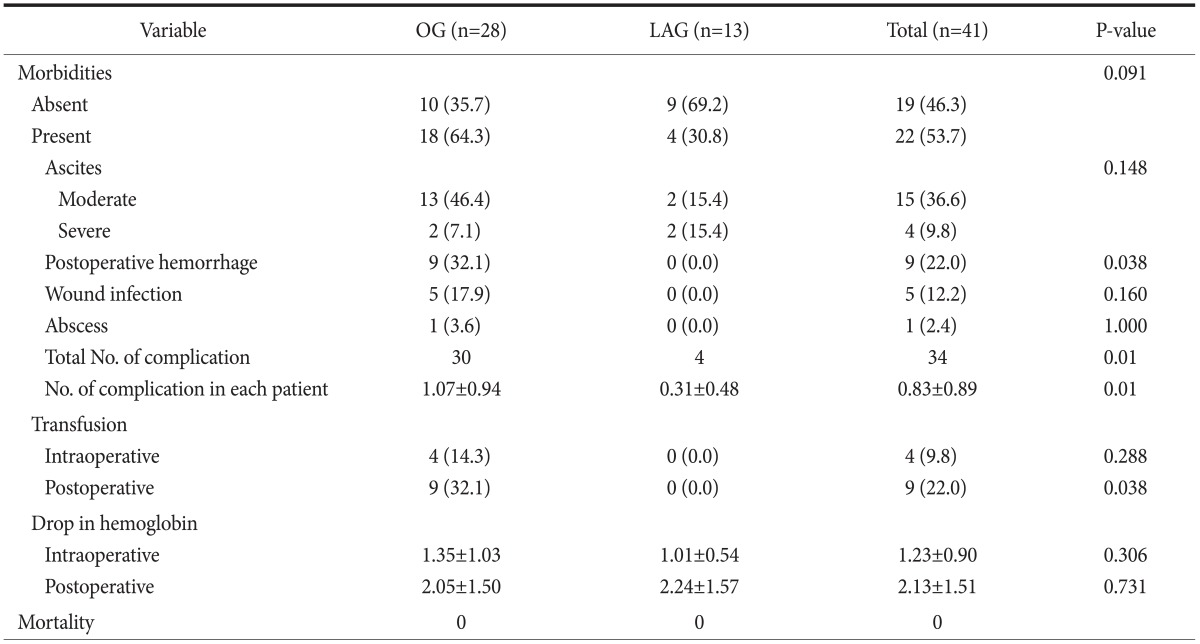

Of the 41 patients, 22 (53.7%) experienced postoperative complications. The most common complications were ascites (moderate, 36.6%; severe, 9.8%; total, 46.4%), postoperative hemorrhage (22.0%), wound infection (12.2%), and intra-abdominal abscess (2.4%). When we compared the number of complications in each patient with the total number of complications in both groups, the open gastrectomy group was found to have more complications than the laparoscopic gastrectomy group (P=0.01). Complications (e.g., postoperative pneumonia or anastomotic leaks) did not occur (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality

Values are presented as number (%), number only, or mean±standard deviation. OG = open gastrectomy; LAG = laparoscopic gastrectomy.

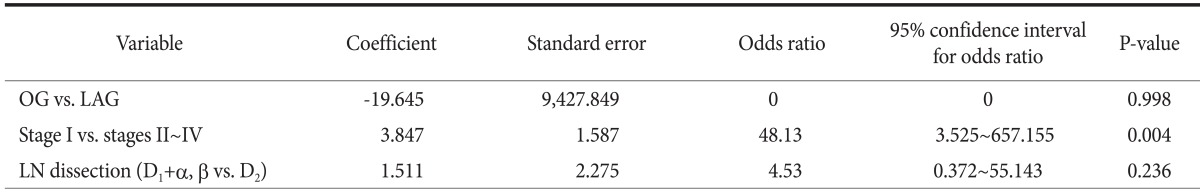

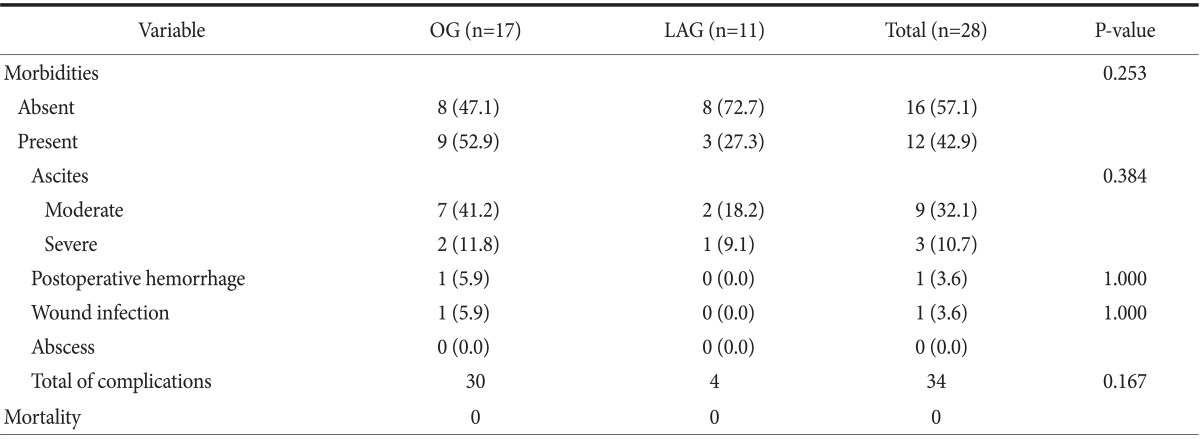

No significant intra- or postoperative hemorrhage in the laparoscopic gastrectomy group was reported. In contrast, significant intra- and postoperative hemorrhage was reported in the open gastrectomy group. When transfusion rates and hemoglobin levels were compared, the only statistically significant difference between the open and laparoscopic gastrectomy groups was postoperative transfusion rate (P=0.038) (Table 2). However, this result appeared to be confounded by the tumor size between the open and laparoscopic gastrectomy groups. Therefore, we performed logistic regression analysis and found no difference in postoperative hemorrhage between the open and laparoscopic gastrectomy groups, and stage was the only significant factor associated with postoperative hemorrhage (P=0.004). This result can possibly be explained by the fact that postoperative hemorrhage in the open gastrectomy group occurred in patients with advanced gastric cancer. The extent of LN dissection was not a risk factor associated with postoperative hemorrhage (Table 3). We then analyzed the morbidities only in pathologic stage I patients (n=28), and no significant difference was found between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of suspected risk factors for postoperative hemorrhage

OG = open gastrectomy; LAG = laparoscopic gastrectomy; LN = lymph node.

Table 4.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality in pathologic stage I patients

Values are presented as number (%) or number only. LAG = laparoscopic gastrectomy; OG = open gastrectomy.

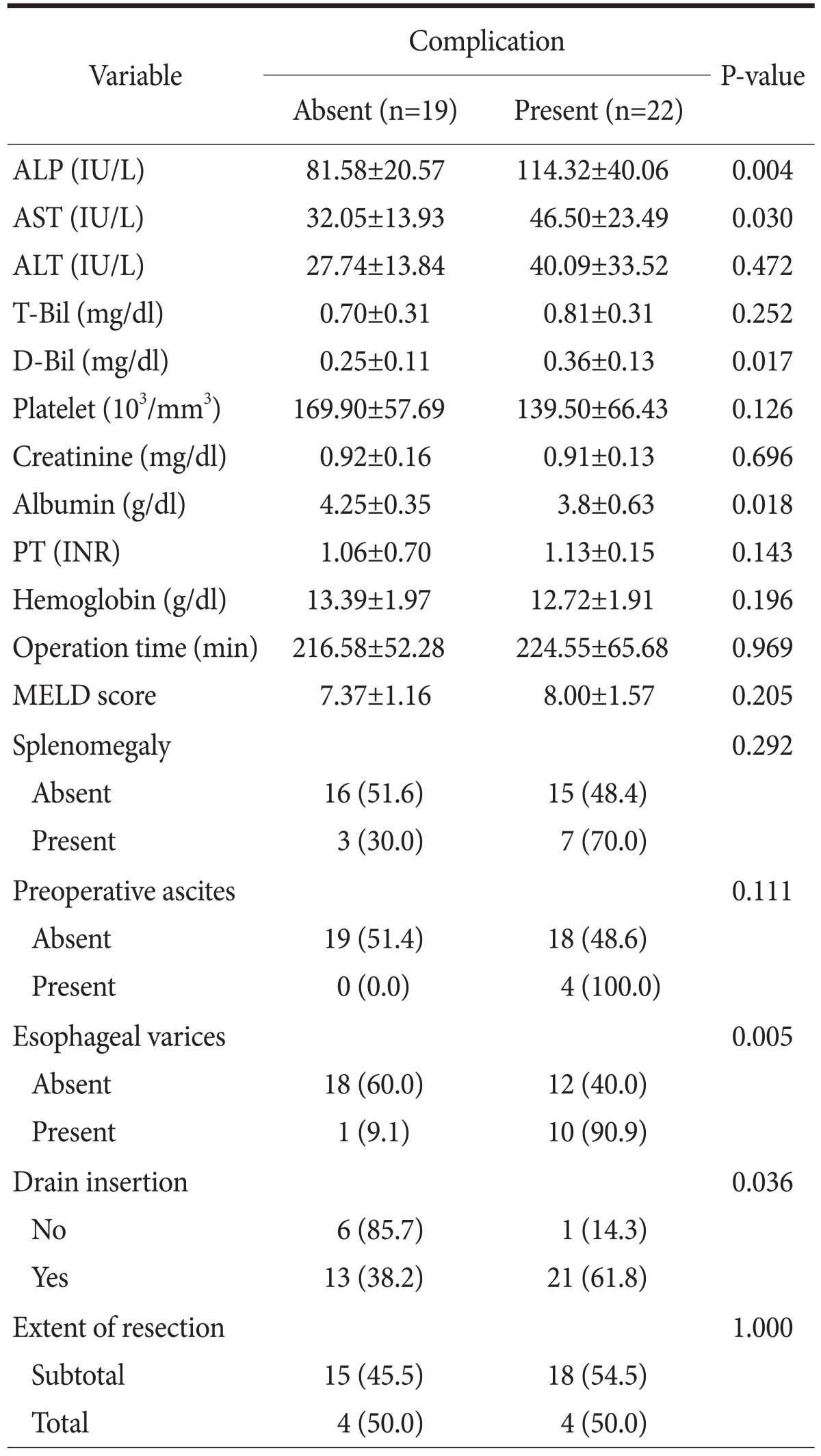

Preoperative laboratory findings, comorbidities, and surgical methods are summarized in Table 5. Independent predictive factors of postoperative morbidity included alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, direct bilirubin, and albumin levels; the presence of esophageal varices; and drainage tube insertion (P<0.05). The extent of resection did not demonstrate a significant difference in complication rates. Of the 8 patients who underwent total gastrectomy, 4 patients experienced postoperative hemorrhage, ascites, and abscess. The overall complication rate was similar in the partial gastrectomy group.

Table 5.

Factors associated with complications

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). ALP = alkaline phosphatase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; T-Bil = total bilirubin; D-Bil = direct bilirubin; PT (INR) = prothrombin time (international normalized ratio); MELD = Model for End-stage Liver Disease.

Discussion

The prevalence of LC is increasing globally. Contributing factors include hepatitis B and C, alcohol consumption, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.8 It has been estimated that 10% of patients with LC undergo surgical treatment in the 2 years prior to their death.9 General anesthesia and surgery may lead to complications in a significant proportion of patients with LC. The mortality rate for patients with LC undergoing surgical procedures has been reported to range from 8.3% to 25% compared with 1.1% in noncirrhotic patients.10-13

Advanced surgical techniques and postoperative management have reduced the mortality and morbidity associated with gastric cancer surgery. Studies have reported the feasibility of D2 LN dissection in Child-Pugh class A patients.3,4 Furthermore, several reports have demonstrated the advantages of laparoscopic surgery compared with open procedure. Advantages include reduced surgical trauma and impaired nutrition; shorter hospital stays; reduced postoperative pain; and earlier return of gastrointestinal function.14-17 Yamada et al.18 reported the feasibility of laparoscopic gastrectomy in patients aged >80 years.

Laparoscopic gastrectomy has recently become a common treatment for treating early stage gastric cancer in East Asian countries. In our institution, most patients with early stage gastric cancer undergo laparoscopic surgery. We also perform many laparoscopic surgeries in patients with gastric cancer and LC.

In patients with gastric cancer and LC, overall complication rates were lower in the laparoscopic surgery group compared with the open gastrectomy group, particularly in regards to postoperative hemorrhage. Among the patients with LC who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy, none required a blood transfusion. Open gastrectomy is the preferred treatment method for patients with advanced gastric cancer. However, cancer stage-not surgical modality-was identified as an independent factor associated with postoperative hemorrhage and complications.

One disadvantage of laparoscopic surgery is that it requires a longer period to perform compared with open procedure. In our study, the mean difference in procedure times between open and laparoscopic surgery was 35 minutes. However, surgery time was not a significant risk factor associated with complications (P=0.969).

Statistically significant factors that were associated with complications included alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, direct bilirubin, and albumin levels in preoperative laboratory findings (Table 5). These results suggest that delayed surgery after using hepatotonics in acute state of liver disease, and a hepatotonic agent, would be helpful in patients with high transaminase levels.

We observed that postoperative morbidity was more common in patients who had drainage tubes inserted compared with patients who did not (Table 5). Similar results were observed in previous reports.3 Several well-constructed prospective studies did not demonstrate benefits from surgically placed closed suction drainage.19,20 However, there was a tendency for surgeons who inserted the drain tube to the patient to expect severe complications such as bleeding and ascites acts as confounding factors. Additional prospective randomized studies should be performed to confirm the effects of drainage tube insertion on the occurrence rate of postoperative complications.

Our study involved a retrospective review of cases of laparoscopic gastrectomy that were performed by surgeons who were inexperienced in performing this procedure. On the other hand, all cases of open gastrectomy had been performed by experienced surgeons. More complications may have occurred as a result of this early learning period compared with laparoscopic surgeries performed more recently. Even when considering the experiences of laparoscopic surgery, there is no significant difference in complication rates between laparoscopic and open gastrectomy group in the patients with gastric cancer and LC.

In conclusion, Laparoscopic gastrectomy does not appear to be inferior to open gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with Child-Pugh class A LC. Gastric cancer stage was closely related with complications, especially postoperative hemorrhage.

References

- 1.Shin HR, Ahn YO, Bae JM, Shin MH, Lee DH, Lee CW, et al. Cancer incidence in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2002;34:405–408. doi: 10.4143/crt.2002.34.6.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YS, Um SH, Ryu HS, Lee JB, Lee JW, Park DK, et al. The prognosis of liver cirrhosis in recent years in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:833–841. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JH, Kim J, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH. Gastric cancer surgery in cirrhotic patients: result of gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4623–4627. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang HJ, Kim JH, Song HH, Woo KH, Kim M, Kae SH, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis who underwent curative surgery for gastric cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:399–404. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:806–810. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochiki E, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: five years' experience. Surgery. 2005;137:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu S, Uchiyama A, Mizumoto K, Morisaki T, Nakamura K, Shimura H, et al. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: is it superior to open surgery? Surg Endosc. 2000;14:27–31. doi: 10.1007/s004649900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble JA, Caces MF, Steffens RA, Stinson FS. Cirrhosis hospitalization and mortality trends, 1970-87. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:192–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson FC, Christophersen EB, Peternel WW, Kirimli B. Preoperative management of patients with liver disease. Surg Clin North Am. 1968;48:907–930. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)38591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziser A, Plevak DJ, Wiesner RH, Rakela J, Offord KP, Brown DL. Morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:42–53. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aranha GV, Sontag SJ, Greenlee HB. Cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: a formidable operation. Am J Surg. 1982;143:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.del Olmo JA, Flor-Lorente B, Flor-Civera B, Rodriguez F, Serra MA, Escudero A, et al. Risk factors for nonhepatic surgery in patients with cirrhosis. World J Surg. 2003;27:647–652. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonetti JP, Aranha GV, Wilkinson WA, Stanley M, Greenlee HB. Umbilical herniorrhaphy in cirrhotic patients. Arch Surg. 1984;119:442–445. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390160072014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi H, Ochiai T, Shimada H, Gunji Y. Prospective randomized study of open versus laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1172–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–237. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000151892.35922.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery. 2002;131:S306–S311. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:168–173. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8808-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada H, Kojima K, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy in patients older than 80. J Surg Res. 2010;161:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez Uslar R, Molina H, Torres O, Cancino A. Total gastrectomy with or without abdominal drains. A prospective randomized trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:562–569. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082005000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Wong Y, Ng IO, Lam CM, et al. Abdominal drainage after hepatic resection is contraindicated in patients with chronic liver diseases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:194–201. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109153.71725.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]