Abstract

Background

Research has been conducted with regard to the development of methods for improving the pharmaceutical effect of ginseng by conversion of ginsenosides, which are the major active components of ginseng, via high temperature or high-pressure processing.

Methods

The present study sought to investigate the anticancer effect of heat-processed American ginseng (HAG) in human gastric cancer AGS cells with a focus on assessing the role of apoptosis as an important mechanistic element in its anticancer actions.

Results and Conclusion

HAG significantly reduced the cancer cell proliferation, and the contents of ginsenosides Rb1 and Re were markedly decreased, whereas the peaks of less-polar ginsenosides [20(S,R)-Rg3, Rk1, and Rg5] were newly detected. Based on the activity-guided fractionation of HAG, ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 played a key role in inducing apoptosis in human gastric cancer AGS cells, and it was generated mainly from ginsenoside Rb1. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 induced apoptosis through activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, as well as regulation of Bcl-2 and Bax expression. Taken together, these findings suggest that heat-processing serves as an increase in the antitumor activity of American ginseng in AGS cells, and ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3, the active component produced by heat-processing, induces the activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, which contributes to the apoptotic cell death.

Keywords: American ginseng, ginsenoside20(S)-Rg3, heat processing, Panax quinquefolius

1. Introduction

Ginseng is a perennial plant belonging to the genus Panax and has been reported to exhibit a wide range of pharmacological and physiological actions [1]. American ginseng (AG) is a popular dietary supplement and one of the most commonly used herbal medicines in the USA, which grows as Panax quinquefolius L. (Araliaceae) in the USA and Canada. By contrast, Panax ginseng Meyer (Araliaceae) has been mainly cultivated in Asia (most notably in Korea and China), and has been used extensively in traditional Chinese medicine [2,3]. Both AG and Asian ginseng extracts have been reported to exhibit free radical scavenging activities, which, from different ginseng species and specific parts, have been thought to be related to their ginsenoside contents [4].

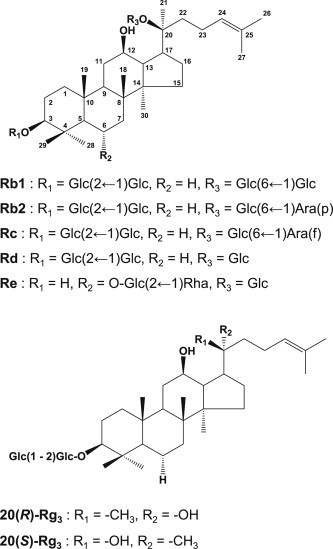

Ginsenosides, which are 30-carbon glycosides derived from the triterpenoid dammarane, as shown in Fig. 1, are regarded as the main active components in AG, as well as Asian ginseng. We previously identified that the structural changes in ginsenosides by heat-processing are closely associated with increased free radical-scavenging activities of AG and Asian ginseng [5,6]. Moreover, we have also recently reported the increased anticancer efficacy of ginsenosides derived from heat-processed Asian ginseng in human gastric cancer cells [7]. Although some of the studies of AG have focused on the antiproliferative activities in cancer cells [8], little is known about the effect of heat processing on the anticancer effect and mechanism of AG on gastric cancer.

Fig. 1.

Structures of ginsenosides contained in American ginseng. –Glc, D-glucopyranosyl; -Rha, L-rhamnopyranosyl; -Ara(f), L-arabinofuranosyl; -Ara(p), L-arabinopyranosyl.

Gastric cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world and is estimated that over 738,000 people die from it every year [9]. Multiple therapeutic strategies are used across the world for the management of operable gastric cancer patients [10]. Various multimodality approaches using chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination of both have been evaluated in an attempt to improve the outcomes of postsurgery. Although there have been advances in the treatment of early gastric cancer, outcomes still remain poor with the majority of patients eventually dying from disease relapse [10].

The present study sought to investigate the anticancer effect of heat-processed AG in human gastric cancer cells with a focus on assessing the role of apoptosis as important mechanistic elements in its anticancer actions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Ginsenoside standards Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, 20(S)-Rg3, 20(R)-Rg3, Rk1, and Rg5 were purchased from Ambo Institute (Seoul, South Korea). Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp (OMe) fluoromethylketone (Z-VAD-fmk) was purchased from BioVision Inc. (Milpitas, CA, USA). Monoclonal antibodies against cleaved caspase-8 and β-actin and polyclonal antibodies against cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-9, Bcl-2, Bax, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Other chemicals and reagents were of high quality and obtained from commercial sources.

2.2. Preparation of ginseng extracts

American ginseng extract was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Heat-processed AG (HAG) was made by steaming AG extract at 120°C and 0.11 MPa for 3 h, and drying at 50°C for 3 d. Heat-processing condition was chosen according to the literature [11]. HAG extract (30 g) was resuspended in water and the water-soluble polysaccharide fraction was separated by Diaion HP 20 (Mitsubishi Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) column chromatography using water as an eluting solution, followed by elution with methanol [12]. Each solution was evaporated in vacuo to give the water eluate (27 g) and methanol eluate (3 g).

2.3. Analysis and structural confirmation of ginsenosides

Analytical reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system was composed of a solvent degasser (G1322A; Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA), binary pump (G1312C; Agilent), an autosampler (G1329B; Agilent), and model 380 Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD; Agilent). ELSD conditions were optimized in order to achieve maximum sensitivity: temperature of the nebulizer was set for 50°C, and N2 was used as the nebulizing gas at a pressure of 2.0 bar. The Phenomenex Luna C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Torrance, CA, USA) was used, and the mobile phase consisted of a binary gradient of solvent A (acetonitrile:water:5% acetic acid in water = 15:80:5) and solvent B (acetonitrile:water = 80:20) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The gradient flow program was as follows: initial; 0% B, 6 min; 30% B, 18 min; 50% B, 30 min; 100% B, 37 min; 100% B, 42 min; 0% B. The amounts of ginsenosides in samples were quantified as reported previously [5]. The standard solutions containing 1–50 μg of each ginsenoside were injected into the HPLC and all calibration curves showed good linearity (R2 > 0.995). The analysis was repeated twice for the verification of repeatability.

2.4. Cell culture

The human gastric cancer AGS cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were grown in RPMI1640 medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, MD, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

2.5. Analysis of cell viability

AGS cells were treated with different concentrations of compounds for 24 h, and cell proliferation was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Control cells were exposed to culture media containing 0.5% (v/v) DMSO. Paclitaxel was used as a positive control (data not shown). In order to examine the possible effects of ginsenosides on caspase-dependent apoptosis, AGS cells were also pretreated with 20 μM, 40 μM, and 60 μM Z-VAD-fmk for 2 hours prior to ginsenosides treatment.

2.6. Western blotting analysis

AGS cells were grown in 6-well plates and treated with the indicated concentration of compounds for 24 h. Whole-cell extracts were then prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) supplemented with 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Proteins (whole-cell extracts, 30 μg/lane) were separated by electrophoresis in a precast 4–15% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) blotted onto PVDF transfer membranes and analyzed with epitope-specific primary and secondary antibodies. Bound antibodies were visualized using ECL Advance Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and a LAS 4000 imaging system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined through analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a multiple comparison test with a Bonferroni adjustment. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and discussion

Many bioactive dietary agents are used alone or as adjuncts to existing chemotherapy to improve efficacy and reduce drug-induced toxicity [13]. For example, epidemiological, as well as experimental studies have shown that diets rich in vegetables and fruit are chemotherapeutically beneficial, exerting the activity to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis against malignancies, including gastric cancer [14–16]. In the present study, we sought to identify the anticancer effect and mechanism of HAG to examine its therapeutic potential.

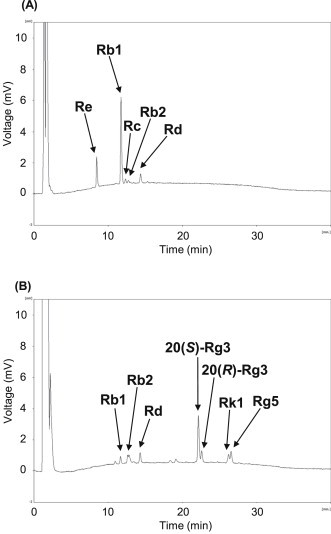

The HPLC chromatogram of AG extract is illustrated in Fig. 2. AG include the typical ginsenosides Re, Rg1, Rb1, Rc, Rb2, and Rd (Fig. 2A). After heat processing at 120°C, the ginsenosides Rb1 and Re were markedly decreased, whereas the peaks of less polar ginsenosides (20(S,R)-Rg3, Rk1, and Rg5) were newly detected at about 23 min and 27 min (Fig. 2B, Table 1). Therefore, ginsenosides Rb1 and Re were more efficiently deglycosylated and transformed into less polar ginsenosides during heat processing than other ginsenosides contained in AG.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of HPLC chromatograms. (A) American ginseng; and (B) heat-processed American ginseng. HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography.

Table 1.

Changes in contents of ginsenosides (μg/mg)

| Re | Rb1 | Rc | Rb2 | Rd | 20(S)-Rg3 | 20(R)-Rg3 | Rk1 | Rg5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | 5.1 | 15.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.4 | — | — | — | — |

| HAG | — | 2.0 | — | 2.2 | 3.0 | 11.3 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

AG, American ginseng; HAG, heat-processed American ginseng.

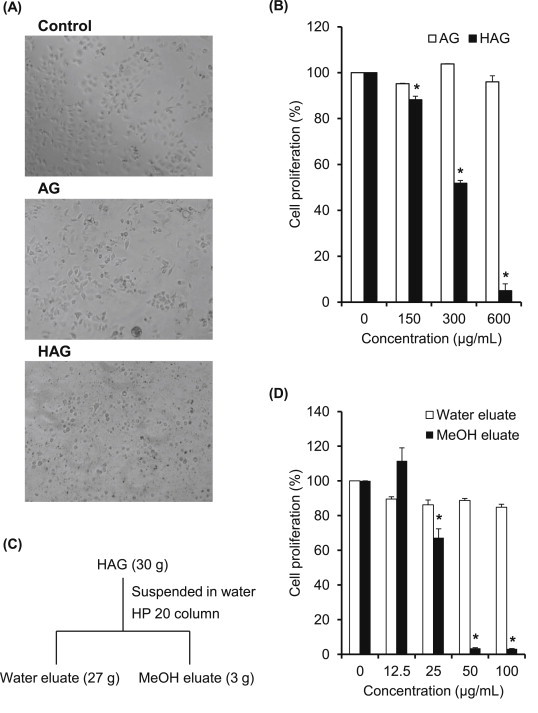

Fig. 3A shows the morphological changes of human gastric cancer AGS cell treated with AG or HAG. The AGS cell line has been shown to grow in athymic mice and to have the same histochemical and cytological characteristics as the specimen taken from the patient [15], and recently, this cell line has been widely used as a model system for evaluating cancer cell apoptosis [17,18]. As a result, HAG was found to induce apoptotic body formation stronger than AG (Fig. 3A), and HAG significantly suppressed AGS cell proliferation from a lower concentration, whereas AG did not suppress cell proliferation at any concentration (Fig. 3B). In addition, we prepared water and methanol eluates from HAG (Fig. 3C) to assess their cell proliferation ability, as well as to find out the main active component. As a result, the methanol eluate almost completely suppressed the cell proliferation from a concentration of 50 μg/mL, although there was no suppression in the water eluate (Fig. 3D). It has been shown that a high concentration of the ginsenosides protopanaxidiol and protopanaxatriol are eluted in methanol fraction [19], suggesting that this antiproliferating activity of the methanol eluate was due to ginsenosides.

Fig. 3.

Changes in effects of American ginseng upon heat-processing on AGS cell proliferation. (A) Morphological changes were confirmed using phase-contrast microscopy. (B) Cells were treated with American ginseng with or without heat-processing at different concentrations (150 μg/mL, 300 μg/mL, and 600 μg/mL) for 24 h. Relative cell proliferation was measured by the CCK-8 assay. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. (C) Schematic description for the preparation of methanol-soluble fraction with HP 20 column chromatography. (D) Cells were treated with water eluate or methanol eluate at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Relative cell proliferation was measured by the CCK-8 assay. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with the vehicle control. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8.

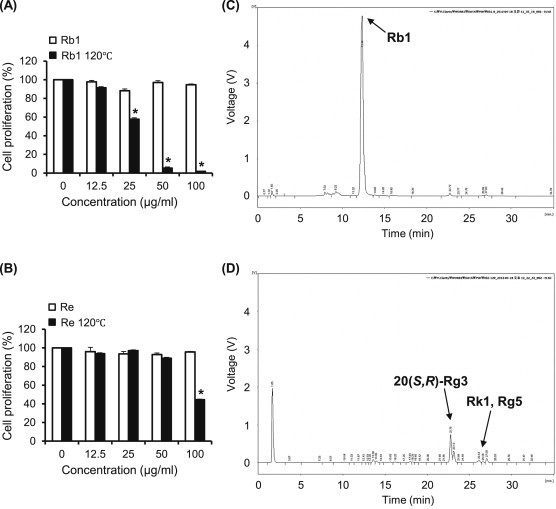

Next, we examined the antiproliferating efficacies of ginsenosides Rb1 and Re with or without heat-processing, because the amounts of these ginsenosides were decreased markedly after heat-processing in AG than in other ginsenosides (Fig. 2A). Both ginsenosides Re and Rb1 showed no efficacy in cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 4) without heat-processing. However, heat processed-Rb1 significantly suppressed cell proliferation from a lower concentration (Fig. 4A), and this result was similarly observed in the case of methanol elute (Fig. 3D). By contrast, ginsenoside Re showed a weak efficacy even at a high concentration of 100 μg/mL (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the major active component of HAG was considered to be related to heat-processed ginsenoside Rb1. From the HPLC analysis of ginsenoside Rb1, prior to and after heat-processing, ginsenoside Rb1 was transformed into ginsenosides 20(S,R)-Rg3, Rk1, and Rg5 after heat-processing at 120°C (Fig. 4Cand D) as shown in AG (Fig. 2). We previously reported that ginsenoside Re gradually transformed into less polar ginsenosides Rg2, Rg6, and F4 upon heat-processing [7]. Considering these, less polar ginsenosides 20(S,R)-Rg3, Rk1, and Rg5 in HAG were generated mainly from ginsenoside Rb1 by heat processing at 120°C.

Fig. 4.

Changes in effects of ginsenosides Rb1 and Re upon heat-processing on AGS cell proliferation. (A) Cells were treated with ginsenoside Rb1 or heat-processed ginsenoside Rb1 at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (B) Cells were treated with ginsenoside Re or heat-processed ginsenoside Re at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Relative cell proliferation was measured by the CCK-8 assay. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. (C) HPLC chromatogram of ginsenoside Rb1 prior to heat-processing. (D) HPLC chromatogram of ginsenoside Rb1 after heat-processing. *p < 0.05 compared with vehicle control. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography.

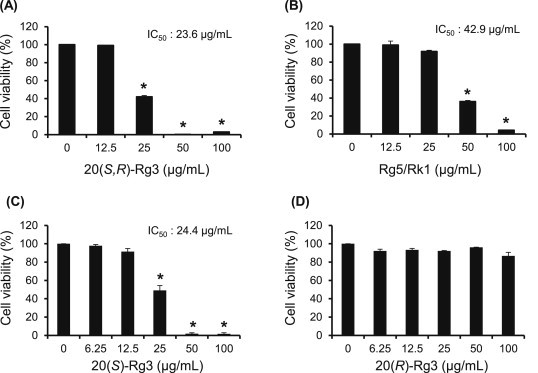

We next examined the antiproliferative effects of 20(S,R)-Rg3 or Rk1/Rg5 mixtures, which were collected using preparative HPLC. As shown in Fig. 5A, 5B, 20(S,R)-Rg3 reduced cancer cell viability stronger than Rk1/Rg5 mixture, and each IC50 value were 23.6 μg/mL and 42.9 μg/mL, respectively. Interestingly, the efficacy of 20(S,R)-Rg3 was similar with that of the methanol eluate, as well as of heat-processed Rb1 (Figs. 3D and 4A). To further confirm the main active component, anticancer effects of 20(S)-Rg3 and 20(R)-Rg3 were individually examined. Subsequently, ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 was obviously identified as the main active component of HAG, while there was no effect in ginsenoside 20(R)-Rg3 (Fig. 5C and D). Thus, anticancer efficacy of HAG was thought to be mainly related to ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3, which was transformed from ginsenoside Rb1 during heat processing.

Fig. 5.

Anticancer effects of ginsenosides on AGS cell proliferation. (A) Cells were treated with ginsenoside 20(S,R)-Rg3 at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (B) Cells were treated with ginsenoside Rg5/Rk1 at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (C) Cells were treated with ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 at different concentrations (6.25 μg/mL, 12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (D) Cells were treated with ginsenoside 20(R)-Rg3 at different concentrations (6.25 μg/mL, 12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Relative cell proliferation was measured by the CCK-8 assay. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with the vehicle control. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8.

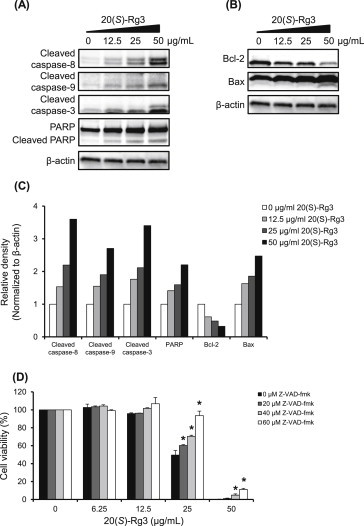

Apoptosis is recognized as an essential mechanism of physiological cell death, and caspases play pivotal roles in cell apoptosis. In line with this notion, we investigated whether ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3-induced cell death is involved in apoptosis. A Western blot analysis was first used to evaluate the expression of proteins involved in the apoptotic response to determine if apoptosis occurs via the intrinsic or extrinsic pathway (Fig. 6A–C). Exposure to ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 for 24 h induced the cleavage of PARP, as well as that of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 significantly triggered the downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of Bax in a dose-dependent manner. Next, we examined the effect of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk on cell proliferation to confirm the role played by caspases in ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3-induced apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 6D, pretreatment with 60 μM Z-VAD-fmk abrogated apoptotic cell death induced by the ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3, although the recovery was weak at the high concentration of 50 μg/mL. These findings demonstrate that ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 induces the activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9, which contributes to apoptotic cell death.

Fig. 6.

Effect of ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 on apoptosis in AGS cells. Western blotting results for (A) extrinsic and (B) intrinsic apoptosis in AGS cells showing the levels of cleaved caspase-8 (18 kDa), Bcl-2 (26 kDa), Bax (20.5 kDa), cleaved caspase-9 (35, 37 kDa), cleaved caspase-3 (17 kDa, 19 kDa), PARP (116 kDa), and cleaved PARP (85 kDa) in AGS cells treated with ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 at different concentrations (12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, and 50 μg/mL) for 24 h. Thirty micrograms of each protein were separated by SDS-PAGE. Beta-actin (45 kDa) was used as an internal control. (C) The panel is the bar graph representing the relative density of cleaved caspase-8, cleaved capase-9, cleaved caspase-3, PARP, Bcl-2, and Bax. The values were normalized with β-actin. (D) Cells were pretreated with the different concentrations (20 μM, 40 μM, and 60 μM) of Z-VAD-fmk for 2 h, followed by exposure to ginsenoside 20(R)-Rg3 at different concentrations (6.25 μg/mL, 12.5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Relative cell proliferation was measured by the CCK-8 assay. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with the ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3-treated value. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; Z-VAD-fmk, Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp (OMe) fluoromethylketone.

Ginsenosides 20(S)-Rg3 and 20(R)-Rg3 are epimers of each other depending on the position of the hydroxyl group (OH) on carbon-20 (Fig. 1), and this epimerization is known to be produced by the selective attack of the OH group after the elimination of glycosyl residue at carbon-20 during the steaming process [20]. In the present study, 20(S)-Rg3 showed stronger anticancer activity than 20(R)-Rg3. Therefore, stereospecificity exists in the anticancer activity of ginsenoside Rg3 epimers. In addition, stereospecificity in the medicinal efficacy of these ginsenosides has been reported by several researchers. The OH group of ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 is better aligned with that of the OH acceptor group in the ion channels than that of ginsenoside 20(R)-Rg3, and thus important for Na+ channel regulation [21]. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 was also reported to provide neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia-induced injury in rat brain through reducing lipid peroxides and scavenging free radicals [22].

In summary, our results suggest that heat-processing improves antitumor activity of AG in AGS cells, and ginsenoside 20(S)-Rg3 serves as a major component through activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 in the event.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This paper was studied with the support of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Institutional Program (2Z03840).

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.Yun T.K. Brief introduction of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:S3–S5. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.S.S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nocerino E., Amato M., Izzo A.A. The aphrodisiac and adaptogenic properties of ginseng. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:S1–S5. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bent S., Ko R. Commonly used herbal medicines in the United States: a review. Am J Med. 2004;116:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu C., Kitts D.D. Free radical scavenging capacity as related to antioxidant activity and ginsenoside composition of Asian and North American ginseng extracts. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2001;78:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang K.S., Yamabe N., Kim H.Y., Okamoto T., Sei Y., Yokozawa T. Increase in the free radical scavenging activities of American ginseng by heat processing and its safety evaluation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee W., Park S.H., Lee S., Chung B.C., Song M.O., Song K.I., Ham J., Kim S.N., Kang K.S. Increase in antioxidant effect of ginsenoside Re-alanine mixture by Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 2012;135:2430–2435. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamabe N., Kim Y.J., Lee S., Cho E.J., Park S.H., Ham J., Kim H.Y., Kang K.S. Increase in antioxidant and anticancer effects of ginsenoside Re-lysine mixture by Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 2013;138:876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B., Wang C.Z., He T.C., Yuan C.S., Du W. Antioxidants potentiated American ginseng-induced killing colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;289:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferlay J., Shin H.R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D.M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain V.K., Cunningham D., Rao S. Chemotherapy for operable gastric cancer: current perspectives. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2011;2:334–342. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang K.S., Lee Y.J., Park J.H., Yokozawa T. The effects of glycine and L-arginine on heat stability of ginsenoside Rb1. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:1975–1978. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayano S., Kikuzaki H., Fukutsuka N., Mitani T., Nakatani N. Antioxidant activity of prune (Prunus domestica L.) constituents and a new synergist. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3708–3712. doi: 10.1021/jf0200164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers A. Botanical medicines for the treatment of cancer: rational, overview of current data, and methodological considerations for phase I and II trials. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:1069–1079. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120005926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M.J., Park H.J., Hong M.S., Park H.J., Kim M.S., Leem K.H., Kim J.B., Kim Y.J., Kim H.K. Citrus Reticulata blanco induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells SNU-668. Nutr Cancer. 2005;51:78–82. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5101_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih P.H., Yeh C.T., Yen G.C. Effects of anthocyanidin on the inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in human gastic adenocarcinoma cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:1557–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou Y., Chang S.K. Effect of black soybean extract on the cuppression of the proliferation of human AGS gastric cancer cells via the induction of apoptosis. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:4597–4605. doi: 10.1021/jf104945x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barranco S.C., Townsend C.M., Jr., Casartelli C., Macik B.G., Burger N.L., Boerwinkle W.R., Gourley W.K. Establishment and characterization of an in vitro model system for human adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1703–1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J.D., Lin S.Y., Ho Y.S., Pan S., Hung L.F., Tsai S.H., Lin J.K., Liang Y.C. Involvement of c-jun N-terminal kinase activation in 15-deoxy-delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2-and prostaglandin A1-induced apoptosis in AGS gastric epithelial cells. Mol Carcinog. 2003;37:16–24. doi: 10.1002/mc.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shehzad O., Ha I.J., Park Y., Ha Y.W., Kim Y.S. Development of a rapid and convenient method to separate eight ginsenosides from Panax ginseng by high-speed counter-current chromatography coupled with evaporative light scattering detection. J Sep Sci. 2011;34:1116–1122. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang K.S., Kim H.Y., Yamabe N., Yokozawa T. Stereospecificity in hydroxyl radical scavenging activities of four ginsenosides produced by heat processing. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5028–5031. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong S.M., Lee J.H., Kim J.H., Lee B.H., Yoon I.S., Lee J.H., Kim D.H., Rhim H., Kim Y., Nah S.Y. Stereospecificity of ginsenoside Rg3 action on ion channels. Mol Cells. 2004;18:383–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian J., Fu F., Geng M., Jiang Y., Yang J., Jiang W., Wang C., Liu K. Neuroprotective effect of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 on cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;374:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]