Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the remineralization potential of bioactive-Glass (BAG) (Novamin®/Calcium-sodium-phosphosilicate) and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) containing dentifrice.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 30 sound human premolars were decoronated, coated with nail varnish except for a 4 mm × 4 mm window on the buccal surface of crown and were randomly divided in two groups (n = 15). Group A — BAG dentifrice and Group B — CPP-ACP dentifrice. The baseline surface microhardness (SMH) was measured for all the specimens using the vickers microhardness testing machine. Artificial enamel carious lesions were created by inserting the specimens in de-mineralizing solution for 96 h. SMH of demineralized specimens was evaluated. 10 days of pH-cycling regimen was carried out. SMH of remineralized specimens was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis:

Data was analyzed using ANOVA and multiple comparisons within groups was done using Bonferroni method (post-hoc tests) to detect significant differences at P < 0.05 levels.

Results:

Group A showed significantly higher values (P < 0.05) when compared with the hardness values of Group B.

Conclusions:

Within the limits; the present study concluded that; both BAG and CPP-ACP are effective in remineralizing early enamel caries. Application of BAG more effectively remineralized the carious lesion when compared with CPP-ACP.

Keywords: Bioactive glass, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate, dental caries, remineralization

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is one of the causes of tooth loss for all human beings across age and gender. Numerous studies have been carried out, which have helped to increase our knowledge of dental caries and reduce the prevalence of dental caries. However, according to The World Oral Health Report, dental caries still remains a major dental disease.[1]

The caries process is well understood as a process of alternating demineralization and remineralization of tooth mineral (Featherstone 1999). The major shortcoming of currently available anti-caries products is the fact that their ability to remineralize enamel is limited by the low concentration of calcium and phosphate ions available in saliva.[2] This has led to the research of many new materials that can provide essential elements for remineralization. Some of them are bioactive glass (BAG), casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP).

BAG is an unique material has numerous novel features; the most important feature is its ability to act as a biomimetic mineralizer, matching the body's own mineralizing traits.[3]

CPP-ACP is also one of the novel calcium phosphate remineralization technology, that shows to promote remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions in various in-vitro and in-vivo studies.[4]

In-vitro pH-cycling technique was introduced, over 20 year ago, to study the effect of caries-preventive regimens and treatments.[5] Many of the researchers have utilized and modified this pH-cycling model to suit their own studies to test different caries-preventive agents.[6,7,8]

Hence the aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the remineralization potential of BAG and CPP-ACP on early enamel carious lesion. The null hypothesis for the present study was that there is no significant difference in the mean microhardness values of the two groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 30 healthy human premolars, which were extracted for orthodontic purposes, were collected. The teeth were cleaned thoroughly to remove any deposits with scaler. Teeth were sectioned 1 mm below the cemento-enamel junction with a slow speed diamond disc. The roots were discarded and the crowns were used for the study. To remove variability in samples, 200 μm of surface enamel was removed from the buccal surface of all teeth with help of 600 grit abrasive paper and confirmed with digital caliper.

A 4 mm × 4 mm working window was marked on the buccal surfaces of all the samples. Samples were then randomly distributed into two groups (n = 15). Group A: BAG containing dentifrice (SHY-NM; Group Pharmaceuticals; India) and Group B: CPP-ACP (GC tooth mousse; Recaldent; GCcorp; Japan) containing dentifrice. The area of the crown other than the working window was covered with nail varnish.

Baseline SMH (B-SMH) measuring

B-SMH was checked with Vicker's microhardness testing machine (VMT) for all the tooth samples in the area of the working window. The indentations were made with VMT at the rate of 25 gram load for 5 seconds.[9] The average microhardness of the specimen was determined from 3 indentations to avoid any discrepancy.

Preparation of demineralizing and remineralizing solutions

The buffered de-/re-mineralizing solutions were prepared using analytical grade chemicals and deionized water. The demineralizing solution contained 2.2 mM calcium chloride, 2.2 mM sodium phosphate, and 0.05 M acetic acid; the pH was adjusted with 1 M potassium hydroxide to 4.4. The remineralizing solution, which contained 1.5 mM calcium chloride, 0.9 mM sodium phosphate, and 0.15 M potassium chloride, had a pH of 7.0.[10]

Preparation of artificial carious lesion

Samples were kept in demineralizing solution for 96 h to produce the artificial carious lesion in the enamel.[10]

After 96 h of initial demineralization SMH (D-SMH) measuring

D-SMH was checked with VMT, similarly as done for B-SMH.

Toothpaste preparation

Dentifrice supernatants were prepared by suspending 12 g of the respective dentifrice in 36-mL deionized water to create a 1:3 dilution. The suspensions were thoroughly stirred with a stirring rod and mechanically agitated by means of a vortex mixer for 1 min. The suspensions were then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 20 min at room temperature, once daily before starting the pH-cycling.

The pH-cycling model

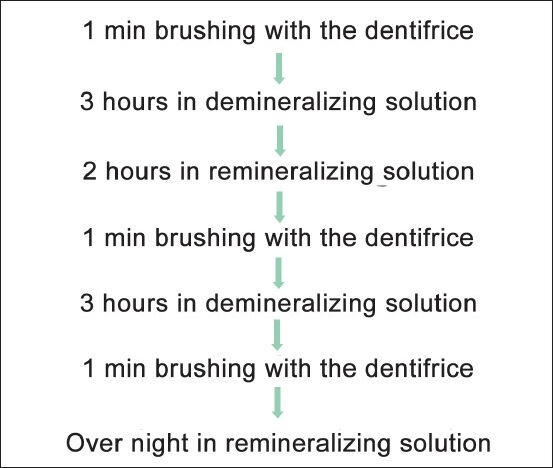

The specimens were placed in the pH-cycling system on a cylindrical beaker for 10 days. Each cycle involved 3 h of demineralization twice a day with a 2 h immersion in a remineralizing solution in between [Figure 1]. A 1-min treatment with a toothpaste solution of 3:1 deionized water to toothpaste, after centrifugation (5 mL/section), was given before the first demineralizing cycle and both before and after the second demineralizing cycle and sections were placed in a remineralizing solution overnight.[10]

Figure 1.

pH-cycling regime

After remineralization SMH (R-SMH) measuring

R-SMH was checked with VMT, similarly as done for B-SMH.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data were conducted using ANOVA and multiple comparisons within groups was done using Bonferroni method (post-hoc tests)

The decision criterion was to reject the null hypothesis if the P < 0.05. If there was a significant difference between the groups, multiple comparisons (post-hoc test) using Bonferroni test was carried out.

RESULTS

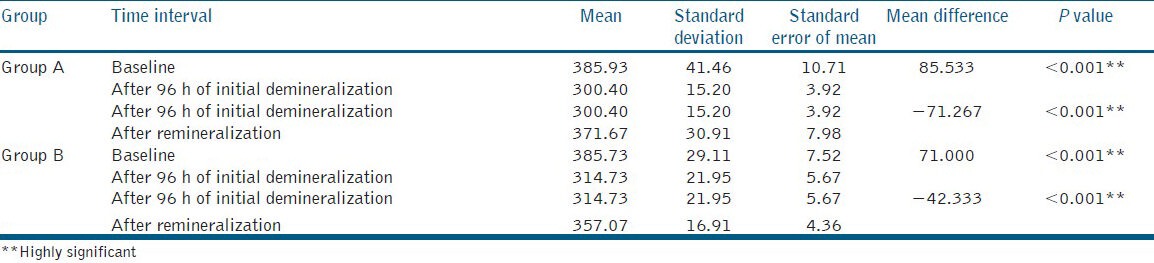

Table 1 gives us the results of comparison of microhardness within each group, from ANOVA and the P value. Mean microhardness in Group A was found to be 385.93 at baseline, 300.40 after demineralization and 371.67 after remineralization. While in Group B mean microhardness was found to be 385.73 at baseline, 314.73 after demineralization and 357.07 after remineralization. These mean values for Group A and Group B were found to be statistically significant from baseline to after demineralization (P < 0.001**) as well as from after demineralization to after remineralization (P < 0.001**).

Table 1.

Mean microhardness within the groups

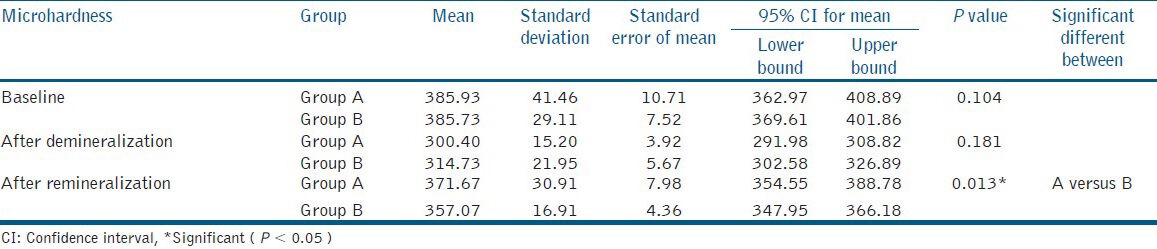

Table 2 gives us the results of comparison of microhardness between the Group A and Group B at different phases of the study.

Table 2.

Mean microhardness between the groups

No significant difference in mean microhardness was observed between both groups at baseline (P > 0.05) and after demineralization (P > 0.05). This indicates that the tooth samples were demineralized to almost the same level of hardness after demineralization, hence giving non-significant result on statistical analysis.

However, the difference in mean microhardness between the groups after remineralization, was found to be statistically significant after remineralization (P < 0.05), indicating changes in the mineralization of the tooth samples.

DISCUSSION

Despite of major advances in the field of cariology, dental caries still remains a major problem affecting human population across the globe. However caries process is now well-understood; much of it has been described extensively in the dental literature.

Early Enamel CARIOUS lesion appears white because the normal translucency of the enamel is lost. Even though initial enamel lesions have intact surfaces, they have a low mineral content at the surface layer when compared to sound enamel; thus showing a lower hardness value at the surface than for sound enamel tissue.[11,12]

When there is acid attack on the tooth surface, the acids lowers the surface pH and diffuse through the plaque, which causes loss of minerals from the enamel and dentine. This mineral loss compromises the mechanical structure of the tooth and lead to cavitation over a long period of time. The subsequent re-mineralization process is nearly the reverse. When oral pH returns to near neutral, Ca2+ and PO43− ions in saliva incorporate themselves into the depleted mineral layers of enamel as new apatite. The demineralized zones in the crystal lattice act as nucleation sites for new mineral deposition.[2]

This cycle is fundamentally dependent upon enamel solubility and ion gradients. Essentially, the sudden drop in pH following meals produces an under saturation of those essential ions (Ca2+ and PO43−) in the plaque fluid with respect to tooth mineral. This promotes the dissolution of the enamel. At elevated pH, the ionic super-saturation of plaque shifts the equilibrium the other way, causing a mineral deposition in the tooth. Over the course of human life, enamel and dentin undergo unlimited cycles of de-mineralization and re-mineralization.[2]

For many years, fluorides have been used as the agent for countering carious tooth process. However recent reviews have concluded that the decline in caries may be at an end or even in reversal, with levels increasing in some areas.[13] Thus, there is a need for developing new biomaterials which can act as an adjunct to the existing fluorides or can individually act as an agent for arresting the carious lesion and their remineralization.

In the present study, we have compared the remineralization potential of two different dentifrices, which are not normally the key active ingredients in the dentifrices largely used.

Considering the importance of the surface layer in caries progression, the evaluation of changes in this region is relevant, thus SMH measurement is a suitable technique for studying de-remineralization process. Micro hardness measurement is appropriate for a material having fine microstructure, non-homogenous or prone to cracking like enamel. SMH indentations provide a relatively simple, non-destructive and rapid method in demineralization and remineralization studies.[9]

Rather than using the traditional pH-cycling method, a modified version[10] was utilized in our study, in an attempt to simulate the real-life situation. This included a 3 h demineralizing cycle twice a day, with one 2 h and one intervening overnight remineralizing cycle, respectively. And to replicate early morning, midday and before bed-time tooth brushing, toothpaste was applied thrice daily. The remineralizing solutions used in the study were created to replicate supersaturation by apatite minerals found in saliva and were similar to those previously utilized by ten Cate and Duijsters.[5]

Even though all the specimens were sectioned from different teeth, the variations among them did not yield any major effect on the progression of demineralization. This was confirmed by the P-value obtained for all the hardness measurements (P > 0.05) before the in-vitro pH cycling commenced. It was therefore reasonable to disregard such variations when analyzing the data after pH cycling.

After the treatment regime with the respective dentifrices, increase in mean microhardness was observed in both groups [Table 1]; this is in accordance with various previous studies carried out for determining the remineralization potential of BAG,[14,15,16] CPP-ACP,[17,18,19] and when compared Group A and Group B showed statistically significant values after pH-cycling regimen [Table 2].

BAG is a ceramic material consisting of amorphous sodium-calcium-phosphosilicate which is highly reactive in water and as a fine particle size powder can physically occlude dentinal tubules.[20]

In the aqueous environment around the tooth, i.e., saliva in the oral cavity, sodium ions from the BAG particles rapidly exchange with hydrogen cations (in the form of H3O+) and this brings about the release of calcium and phosphate (PO4−) ions from the glass.[21] A localized, transient increase in pH occurs during the initial exposure of the material to water due to the release of sodium. This increase in pH helps to precipitate the extra calcium and phosphate ions provided by the BAG to form a calcium phosphate layer. As these reactions continue, this layer crystallizes into hydroxycarbonate apatite (HCA).[20]

Unlike other calcium phosphate technologies, the ions that BAG release form HCA-(a mineral that is chemically similar to natural tooth mineral) directly, without the intermediate ACP phase. These particles also attach to the tooth surface and continue to release ions and re-mineralize the tooth surface after the initial application. The deposits are firmly attached and are not removed by thorough washing and brushing. These particles have been shown, in in-vitro studies, to release ions and transform into HCA for up to 2 weeks.[22]

A study was carried out to determine the remineralizing effects of BAG on bleached enamel. It concluded that BAG deposits were found on the enamel surface of all the specimens, suggesting that they may act as a reservoir of ions available for remineralization at sites of possible demineralization.[23] This may explain the higher hardness values of BAG dentifrice after remineralization.

The present study also revealed that CPP-ACP remineralized enamel lesion in human enamel in-vitro. CPP-ACP is calcium phosphate-based delivery systems containing high concentrations of calcium phosphate.

The roles of CPP-ACP has been described as - localization of the ACP on the tooth surface and buffer the free calcium and phosphate ion activity, thereby helping in maintaining the role of super saturation. The CPP stabilizes the calcium and phosphate in a metastable solution facilitating high concentration of the Ca2+ and PO43− which diffuses in the enamel lesion when CPP-ACP comes in contact with the lesion.[24]

However the lower hardness values for CPP-ACP may be due to its amorphous nature; which does not adhere to the enamel surface, unlike BAG gets attached to tooth, hence not remineralizing the tooth surface for a longer period of time to enhance its hardness.

A study investigated the enamel remineralization potential of CPP-ACP and BAG, showed that, after scanning electron microscope analysis it was clearly seen that although both group samples had plugs that sealed the fissures formed by demineralization, BAG plug appeared to be more compact and intimately attached to the enamel surface. The deposits formed by CPP-ACP were smaller and amorphous, while BAG created larger, more angular deposit.[21] This may also explain the high values of hardness for BAG as compared to CPP-ACP in the current study; as BAG attaches more intimately and compactly to the tooth surface.

CONCLUSION

Under the current in-vitro experimental conditions it can be concluded that both BAG and CPP-ACP are capable to remineralize early carious lesion and also that BAG has a better remineralization potential than CPP-ACP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen PE. Socio-behaviour risk in dental caries — International perspective. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:274–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winston AE, Bhaskar SN. Caries prevention in the 21 st century. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1579–87. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hench LL, West JK. Biological application of bioactive. Life Chem Rep. 1996;13:187–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds EC. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate: The scientific evidence. Adv Dent Res. 2009;21:25–9. doi: 10.1177/0895937409335619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ten Cate JM, Duijsters PP. Alternating demineralization and remineralization of artificial enamel lesions. Caries Res. 1982;16:201–10. doi: 10.1159/000260599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itthagarun A, Wei SH, Wefel JS. The effect of different commercial dentifrices on enamel lesion progression: An in vitro pH-cycling study. Int Dent J. 2000;50:21–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara AT, Magalhães CS, Serra MC, Rodrigues AL., Jr Cariostatic effect of fluoride-containing restorative systems associated with dentifrices on root dentin. J Dent. 2002;30:205–12. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paes Leme AF, Tabchoury CP, Zero DT, Cury JA. Effect of fluoridated dentifrice and acidulated phosphate fluoride application on early artificial carious lesions. Am J Dent. 2003;16:91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lata S, Varghese NO, Varughese JM. Remineralization potential of fluoride and amorphous calcium phosphate-casein phospho peptide on enamel lesions: An in vitro comparative evaluation. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:42–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.62634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itthagarun A, King NM, Yuen-Man Cheung. The effect of nano-hydroxyapatite toothpaste on artificial enamel carious lesion progression: An in-vitro pH-cycling study. Hong Kong Dent J. 2010;7:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koulourides T, Feagin F, Pigman W. Remineralization of dental enamel by saliva in vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965;131:751–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb34839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arend J, Cate JM. Tooth enamel remineralization. J Cryst Growth. 1981;53:135–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagramian RA, Garcia-Godoy F, Volpe AR. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. Am J Dent. 2009;22:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Featherstone JD, Shariati M, Brugler S, Fu J, White DJ. Effect of an anticalculus dentifrice on lesion progression under pH cycling conditions in vitro. Caries Res. 1988;22:337–41. doi: 10.1159/000261133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ten Cate JM. In vitro studies on the effects of fluoride on de- and remineralization. J Dent Res. 1990;69(Spec No):614–9;634. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahid Golpayegani M, Sohrabi A, Biria M, Ansari G. Remineralization effect of topical novamin versus sodium fluoride (1.1%) on Caries-Like lesions in permanent teeth. J Dent (Tehran) 2012;9:68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahiotis C, Vougiouklakis G. Effect of a CPP-ACP agent on the demineralization and remineralization of dentine in vitro. J Dent. 2007;35:695–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tantbirojn D, Huang A, Ericson MD, Poolthong S. Change in surface hardness of enamel by a cola drink and a CPP-ACP paste. J Dent. 2008;36:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker G, Cai F, Shen P, Reynolds C, Ward B, Fone C, et al. Increased remineralization of tooth enamel by milk containing added casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dairy Res. 2006;73:74–8. doi: 10.1017/S0022029905001482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gjorgievska ES, Nicholson JW. A preliminary study of enamel remineralization by dentifrices based on Recalden (CPP-ACP) and Novamin (calcium-sodium-phosphosilicate) Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2010;23:234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson OH, Kangasniemi I. Calcium phosphate formation at the surface of bioactive glass in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 1991;25:1019–30. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820250808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burwell AK, Litkowski LJ, Greenspan DC. Calcium sodium phosphosilicate (NovaMin): Remineralization potential. Adv Dent Res. 2009;21:35–9. doi: 10.1177/0895937409335621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gjorgievska E, Nicholson JW. Prevention of enamel demineralization after tooth bleaching by bioactive glass incorporated into toothpaste. Aust Dent J. 2011;56:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grenby TH, Andrews AT, Mistry M, Williams RJ. Dental caries-protective agents in milk and milk products: Investigations in vitro. J Dent. 2001;29:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]