Abstract

Background:

Internalizing and externalizing disorders in children and adolescents have been described in many countries. This study was performed to better understand the effect of culture on emotion regulation, and aimed to identify the relationship between emotion regulation and psychopathology in children.

Methods:

Participants were 269 children from Iran and Germany who voluntarily agreed to participate. Groups were defined by cultural background, Participants completed the Children Emotion Management Scale (CEMS), Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), and the Youth self-report YSR questionnaires. Data were analyzed using Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) with post-hoc Scheffe tests conducted to identify the exact nature of group differences.

Results:

There were significant main effect of country (P < 0.001) and sex (P = 0.003). For CEMS, but no significant interaction For CERQ there was a significant main effect of country (P <0.001), but no main effect of sex nor an interaction. MANOVA analyses for internalizing and externalizing symptoms as measured by the YSR indicated significant main effects of country and sex, but the interaction did not reach significance (P=0.088).

Conclusions:

A main result of the study showed that children in Iran report more internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Culture and emotional expression may explain differences between Iranian and German children. It seems to be difficult for young children in Iran to express themselves, this may be because they are expected to show respect to maintain harmony in the family.

Keywords: Coping strategies, culture, emotion regulation, externalizing, internalizing.

INTRODUCTION

Internalizing and externalizing disorders in children and adolescents have been described in many countries.[1,2] However, some investigators have claimed that the underlying causes may differ[3,4] depending on cultural and social context.[5,6] Internalizing problems manifested as social withdrawal, somatic complaints, and loneliness have been associated with an overregulation of emotions[7,8,9] whereas externalizing problems manifested as difficulty in adjusting and coping with situations and exhibiting under-controlled responses of sadness and anger are due to under regulation of emotions.[9] Therefore, the experience of emotion and emotion regulation may play an important role in the development of both internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Emotion regulation is extrinsic or intrinsic process responsible for changing or controlling emotional reactions in order to achieve personal goals.[5] There is some evidence that psychopathology in children is related to poor emotion regulation strategies.[10,11] Externalizing disorders may be due to inadequate regulation or insufficient ability to inhibit behavior and control attention in cognitive processes.[12,13] On the contrary internalizing problems are often linked with low attention control or inability to control negative emotionality as indicated by high levels of rumination, sadness, anxiety, and depression.[14,15,16,17]

There is some evidence that the expression of emotions, as well as the process of emotion regulation and the use of emotion regulation strategies differ across cultures.[18,19,20] Individualistic cultures (e.g., Germany) place more emphasis on self-independent, autonomous and personal goals. In contrast the collective cultures (e.g., Iran) tend to stress on being dependence and belonging to the others, having collective identity, depending and belonging to a group with values boosting group harmony, cohesion and group goals.[21] however, the Western cultures are more individualistic than Eastern cultures, with Iran somewhere around the midpoint between individualistic and collectivistic cultures.[22,23]

There are several studies indicating that differences and similarities in emotion regulation strategies are influenced by cultural values, gender and ethnic.[24,25,26]

In this study, we investigated emotion regulation strategies, coping strategies, and psychopathology in school-children in Germany and Iran using self-report instruments. In order to control the influence of the social/cultural environment, we included two additional groups of Iranian children living in Germany and German children living in Iran. We expected these two groups to show different emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology as compared with groups of children in their original country. It was expected that Iranian children in Iran would show (1) More internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as (2) more inhibition and suppression than German children in Germany. According to the association between emotion regulation and psychopathological symptoms, it was further hypothesized that (3) there would be a stronger association in Iran than in Germany. Moreover, according to previous research.[26,52,41,27] we (4) assumed that both psychopathology and emotion regulation should be influenced by gender.

METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of 269 children from Iran and Germany, divided into four groups: Iranian children in Iran (II), German children in Germany (GG), German children in Iran (GI) and Iranian children in Germany (IG). The samples were drawn from both gender in the cities of Karaj (Iran) and Freiburg (Germany).

Procedure

The research goals and methods were explained to school directors in both cities, and upon agreement to participate, informed consent forms were sent to children and their parents. The Iranian sample in Iran was collected between September 2010 and the end of November, the German sample in Germany was collected between December 2010 and May. 2011, the German sample in Iran was collected in September 2011, and the Iranian sample in Germany was collected between February 2012 and the end of June. In class, participants were provided with instructions for completing the questionnaire. They were aged between 11-14 years. Of 680 eligible children, a total number of 103 II (female n=48, male n=55), 24 GI (female n=14, male n=10), 119 GG (female n=78, male n=41) and 23 IG (female n=11, male n=12) completed the questionnaires.

Measures

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation was measured using the Children's Emotion Management Scale (CEMS);[27] which assesses children's perceptions of their anger (CEMS-A) and sadness (CEMS-S) management styles with 27 items answered on a three-point Likert scale (1 = hardy ever, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = often). Both the CEMS-S and the CEMS-A consist of three subscales: (a) Inhibition (b) dysregulation expression, and (c) emotion regulation coping. The inhibition scale assesses suppression of emotional expression, for instance when the child feels sad or angry but does not show it externally. The dysregulation expression scale assesses over and under-controlled expression or inappropriate expression of emotions (e.g., screaming). The emotion regulation coping scales assesses the child's ability to adapt and control emotions and show a healthy response to emotions. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall CEMS in our sample was α = 0.764. The Cronbach's alpha in II was α = 0.713, for GG was α = 0.785, for German children in Iran was α = 0.715 and for Iranian children in Germany was α = 0.672.

Coping strategies

Coping strategies were measured using the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (long version), developed by Garnefski et al.[28,29] This questionnaire consists of 36 self-report items assessing cognitive coping strategies following negative life events, developed by. The CERQ measures nine cognitive coping strategies (five functional and four dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies) in children and adolescents. All CERQ subscales consist of four items and statements that have to be rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. The nine subscales are self-blame, other blame, rumination, catastrophe, putting into perspective, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, and acceptance and refocusing on planning. The Cronbach's alpha in II was α = 0.843, for GG was α = 0.891, for GI was α = 0.829, and for Iranian students in Germany was α = 0.842.

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms were measured using the Youth Self-Report (YSR) questionnaire developed by Achenbach[30] for adolescents between 11-18 years. The YSR is a self-report questionnaire divided in two parts; 1) competencies, and 2) problems.[30] The questionnaire contains items concerning activities, social relationships and academic performance as well as 112 items assessing emotional and behavioral problems during the preceding 6 months. The response format for the problem item is 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true) and 2 (very true). The YSR allows examination of two groups of syndromes; Internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Internalizing problems comprise social withdrawal, somatic complaints, and anxiety/depression, while externalizing problems include delinquent and aggressive behavior. The Cronbach's alpha for the overall YSR in our samples demonstrated high reliability α = 0.929. The Cronbach's alpha in II was α = 0.950, for GG was α = 0.930, for GI was α = 0.874 and for IG was α = 0.948.

RESULTS

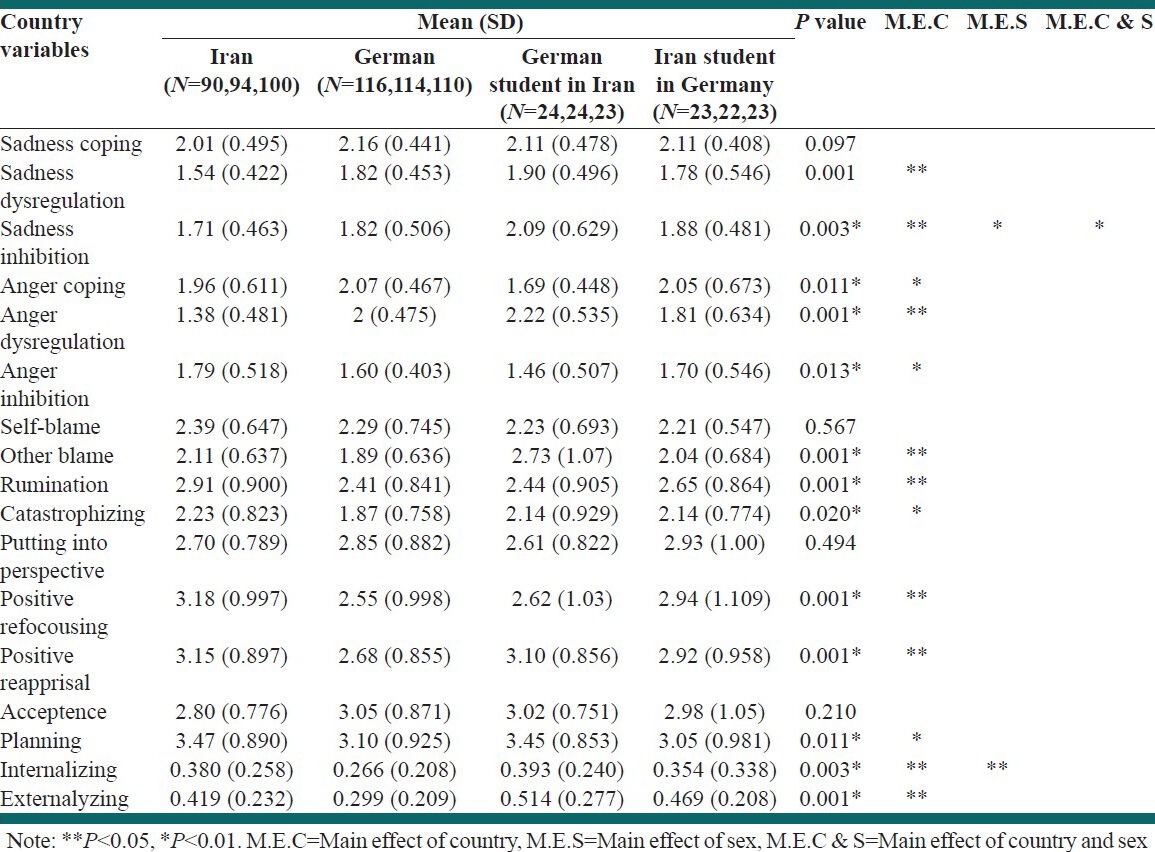

Analysis of variance showed significant main effects of country (F(24, 690.8) =7.206, P< 0.001) and sex, (F(8, 238) =3.050, P= 0.003), but no significant interaction between country and sex. A main effect of country was significant in three subscales of CEMSS sadness dysregulation expression, (F(3, 245)=7.366, P< 0.001), sadness coping (F(3, 245) = 2.129, P= 0.097) and sadness inhibition, (F(3, 245)= 4.777, P= 0.003). The main effect of sex and interaction between sex and country was significant for sadness inhibition, (F(1, 245) = 6.82, P=0.010), and (F(3, 245) =2.695, P=0.047) respectively.

A significant main effect of country was found for three subscales of CEMS anger; anger inhibition, (F(3, 245) = 3.670, P= 0.013), anger dysregulation (F (3, 245)= 31.693, P= <0.001), and anger coping (F(3,245) = 3.784, P= 0.011). There were no significant main effects of sex and or interactions between sex and country.

Post hoc Scheffe tests indicated that in children emotion management in sadness, II reported less sadness dysregulation than GG (P < 0.001) and GI reported more sadness dysregulation than II (P = 0.010), GI reported more sadness inhibition than II (P = 0.014) and in sadness coping there were not significant differences between four groups.

Differences between II, GG, GI and Iranian Student in Germany (IG) in the reporting cognitive strategies

MANOVA for CERQ showed that the main effect of country was significant (F(27, 695.7) = 4.10, P = < 0.001), but there was no significant main effect of sex and no interaction. There were no significant main effects of country for self-blame, putting into perspective or acceptance (P > 0.05), but main effects for country were found for other-blame (F (3, 246) = 8.95, P = < 0.001), rumination (F (3, 246) = 6.48, P = < 0.001), catastrophe (F (3, 246) =3.35, P = 0.020), positive refocusing (F (1,191) =7.90, P < 0.001), positive reappraisal (F (3, 246) =6.53, P= < 0.001), and planning (F (3, 246) = 3.77, P = 0.011).

The results of Scheffe Post hoc test to compare the four groups on the nine subscales showed that there were no group differences on self-blame, putting in to perspective and acceptance.

For other-blame GI reported more than other groups (P < 0.010) and GG reported less other-blame than GI (P = < 0.001). II reported more rumination (P = 0.001), catastrophe (P =0.017), positive refocusing (P < 0.001), and positive reappraisal (P = 0.003) than GG.

Differences between II, GG, GI, and IG in the reporting YSR

MANOVA analyses of the Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems scales of the YSR indicated main effect of country (F(6, 506) = 5.566, P = <0.001*), a main effect of sex (F(2, 253) = 5.687, P = 0.004*), but the country and sex interaction was not significant (F(6, 506) = 1.849, P = 0.088).

A main effect of country was found for internalizing behavior problems (F(3, 14.86) = 4.869, P = 0.003), and also for externalizing behavior problems (F(3, 254) = 10.063, P = < 0.001*).

There were sex differences in internalizing behavior problems (F(1, 254) = 8.149, P = 0.005*); girls report more internalizing problems than boys but there was no main effect for sex in externalizing behavior problems (F(1, 254) = 0.003, P = 0.959).

For internalizing behavior problem II report more than GG and other groups (P = 0.002). For externalizing behavior problem, GI reported more than GG and other groups (P = 0.014) and GG report less externalizing behavior problem than other groups (P < 0.002). Results, mean and standard deviation have been showed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Country Differences in mean score and standard deviation children emotion management scale (sadness, anger) Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, and youth self-report

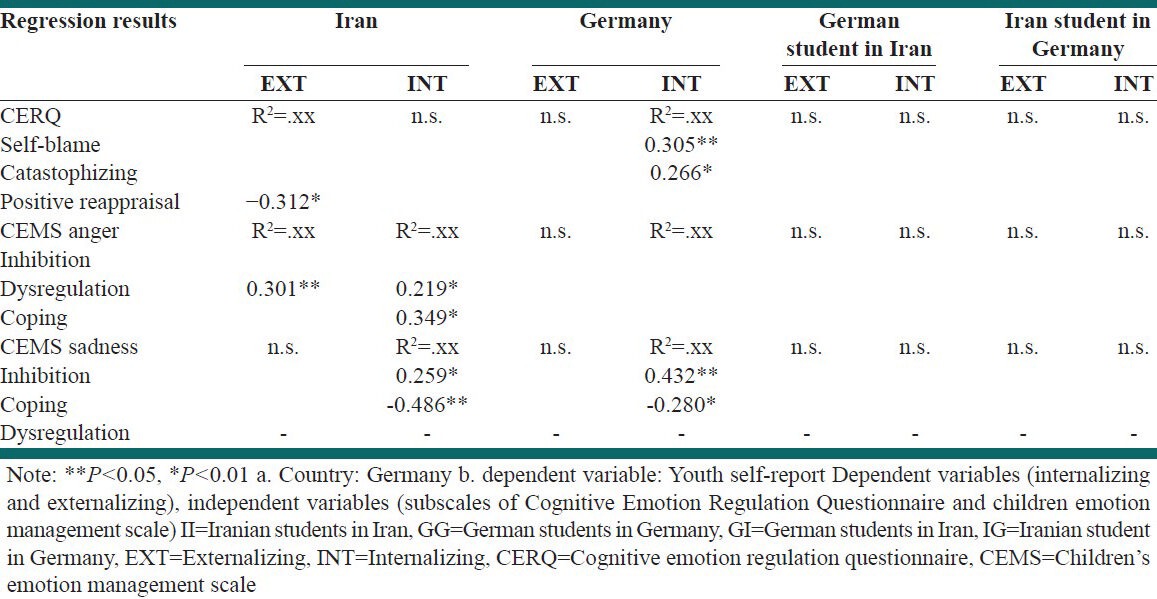

To explore the relationships between CERQ, CEMS and internalizing and externalizing problems, the linear regression analysis was performed separately in each group [Table 2]. The results showed that more internalizing symptoms were predicted by higher CERQ scores on self-blame and catastrophe GG (β = 0.266, P = 0.023), (β = 305, P = 0.009). There were no other significant predictors of internalizing symptoms in the other groups. Results also showed that in II externalizing symptoms were predicted by lower CERQ positive reappraisal scores.

Table 2.

Regression analysis between cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire, children emotion management scale, and internalizing and externalizing (youth self-report)

Regression analysis results for CEMS, externalizing problems and internalizing problems YSR indicated more externalizing symptoms were predicted by higher CEMS-A scores on anger dysregulation in II(β =.301, P = 0.008). In addition, more internalizing symptoms were predicted by higher CEMS-A scores on anger dysregulation anger coping and in II (β =.219, P = 0.042) (β =.349, P = 0.017) and by higher CEMS-S scores on sadness inhibition (β =.259, P = 0.025). Results also showed that in II internalizing symptoms were predicted by lower CEMS-S sadness coping (β =-.486, P < 0.000). The result showed more internalizing symptoms were predicted by higher CEMS-S scores on sadness inhibition in GG (β =.432, P < 0.000). Results also showed that in GG internalizing symptoms were predicted by lower CEMS-S sadness coping (β =-.280 P = 0.011). There were no predicted able internalizing and externalizing problems with CERQ and CEMS in GI and IG.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to identify the relationships between internalizing and externalizing problems, and emotion regulation and cognitive strategies, among Iranian children and German children in both Iran and Germany. German children, from an individualist culture, and Iranian children from a collectivist culture, have different experiences and beliefs. Our study shows that Iranian children report more internalizing and externalizing symptoms than German children do. Moreover, Iranian children use more suppression and inhibition strategies than German children. Therefore, Iranian children show stronger relation between emotion regulation and psychopathology than German children. Overall, we found that II, GI, and IG show more internalizing problems than GG, and females show more internalizing problems than males. Beside influences by society and environment, cultural differences between Germany and Iran in norms, values and beliefs could be one explanation for the use of different emotion regulation strategies and differences in psychopathology. In addition, the results showed that women are more prone to internal problems than men. Whether these sex differences are the result of a higher emotional sensitivity, social and cultural influences on women or due to other psychological variables are unclear and needs further research.[7]

We also found that II report lower sadness inhibition, sadness coping and sadness dysregulation than other groups. Furthermore, IG reported higher sadness inhibition and sadness dysregulation than other groups and GG reported high score in sadness coping than other groups.

Iranian children in Iran reported higher anger inhibition and lower anger dysregulation than other groups, but GI reported lower anger inhibition and anger coping and higher anger dysregulation than other groups. GG reported higher anger coping than other groups. All of these results indicate that Iranian children report more inhibition expression (except for sadness) and anger suppression than German children.

Research has shown that development of emotion regulation in non western cultures is related to empathy, interpersonal adjustment, and norm assimilation[32,19,51]. In western cultures, however, development of emotion regulation is associated with self-expression and autonomy.[27,31,32,19]

Other research has also reported that suppression may be accepted for Eastern countries or in collective cultures, as a strategy to maintain social harmony, that is for Chinese children, inhibition is an adaptive behavior.[33] Research by Zeman et al. showed that when children express an emotion in a dysregulated way, it is not culturally acceptable. In this study, II reported higher scores on the CERQ subscales self-blame, rumination, catastrophe, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal and planning, and lower acceptance scores than other groups. GG reported lower other-blame, rumination, catastrophe positive refocus, and positive reappraisal and higher acceptance than other groups. GI reported higher score in other blame and lower putting in to perspective than other groups. IG reported higher putting in to perspective and lower in self-blame and planning strategies than other groups. Zhu et al.[34] compared research across different countries and reported Chinese sample use more self-blame and other-blame. Whereas American sample report more rumination, catastrophe, refocus on planning, and positive reappraisal. Research has showen that dysfunctional cognitive coping strategies are positively correlated with internalizing disorders such as anxiety and depression.[28,29]

We also found that anger dysregulation expression and anger coping, and inhibition of the expression sadness are predictors for showing symptoms of internalizing problem and coping with sadness was negatively correlated with internalizing problem in II. Also, anger dysregulation was strongly correlated with externalizing problems in II. To know about GG, results indicated sadness inhibition had stronger correlation with internalizing problem as compared with II and negative correlation between sadness coping with internalizing problem. We found a main effect of sex in sadness inhibition in accordance with research by Young and Zeman[35,36], who proposed that differences in emotional expression may be a result of differences in emotional rules in society for males and females (e.g. higher acceptance of intensive emotional expression in women). In Caucasian samples, males report more suppression of sadness and females report more inhibition of anger expression. Several studies conducted in western countries have reported that poor emotion regulation is related to psychopathological outcomes in children and adults.[9,37,38,39] In several studies dysregulated expression, inhibition and coping with anger and sadness have been found to be predictors for internalizing and externalizing disorder. For example, Zeman et al.[9] reported poor coping with anger and sadness inhibition are correlated with externalizing problem. Moreover, maladaptive coping with anger and anger inhibition were predictive depressive and anxious symptoms, and research has supported the hypothesis that coping with anger would predict internalizing symptoms.[9] Other research by Suveg and Zeman[40] reported dysregulated expression of sadness and anger and coping less adaptively by sadness and anger. John and Gross[41] considering healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation, reported suppression to be associated with negative outcomes and reappraisal to be correlated with positive outcomes. Some researchers have noted that people differ in expression of emotions, which may be a resulted of social context or cultural differences (values and beliefs).[41,42] In II, reported anger dysregulation expression was correlated with internalizing. It may be that in this culture the expression of anger threatens social relationships, which makes it difficult for Iranian children to express their emotions.

Lack of control and over one's emotions can be reason for many different forms of internalizing and externalizing problem.[43] Dysregulation of anger and sadness has been linked with different forms of psychopathology.[7] Child self-reports of internalizing symptoms have been associated with children reporting more dysregulated expression of sadness and anger.[44]

Ours results indicated a negative correlation between positive reappraisals and externalizing problem in II. Several studies have also shown that positive reappraisal such as functional coping is negatively correlated with internalizing problem in Iran.[45,46]

In GG, we found that more internalizing symptoms were predicted by higher scores in self-blame and catastrophe. This is consistent with the idea that in western countries personal success may be more strongly related to the individual's ability for self-control and the empirical finding that in western cultures higher scores in depression are closely related to more self-blame. Other research has also reported that catastrophe is correlated with internalizing problem.[47,48] Research by Ehring et al.[49] also indicated that depressed participants reported more dysfunctional strategies rumination and catastrophe. Research in Iran has also found a correlation between rumination and depression.[50,51,52] In this study, the II group scored low in acceptance strategies and this group showed also more symptoms of behavior problems, in accordance with the finding by Ehring et al. that lack of acceptance is linked with depression.

CONCLUSIONS

Children in Iran showed more internalizing and externalizing symptoms, which may be because of differences in values and beliefs in Iran. It is difficult for young children to express themselves, may be because they have to show respect in order to maintain harmony in the family. It is noteworthy that in Iran, early puberty is another reason for conflict between young children and parents and society. Identity crisis is another reason for conflict, and may be a cause of symptoms of behavior problems in young adolescents. Possibly, one important influence for more behavior problems in Iranian children could be a change in young Iranian people to more individualistic values, which may lead to increasing conflicts with collective culture and collective family norms. If individuals are not able to control or manage their emotions in daily life, they will be prone to show symptoms of internalizing or externalizing problems. Thus, high scores in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in IG and GI may have to do with difficulties to cope with the situation in a foreign country, including such issues as language problems, and understanding the values in their new society. Finally, differences in the socio-economic status of the family, parental educational levels, and other similar factors could be other possible explanations for differences between the Iranian and German children in this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.4th ed. Washington: Author; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva, Switzerland: The WHO World Health Report on mental health, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinman A. New York: The Free Press; 1988. Rethinking psychiatry: From cultural category to personal experience. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis-Fernandez R. Cultural formulation of psychiatric diagnosis. Case No. 02. Diagnosis and treatment of nervous and antiques in a female Puerto Rican migrant. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1996;20:155–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00115860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saarni C. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. The Development of Emotional Competence. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullin BC, Hinshaw SP. Emotion regulation and externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 523–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeman J, Shipman K, Suveg C. Anger and Sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31:393–8. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilliom M, Shaw DS, Beck JE, Schonberg MA, Lukon JL. Anger regulation in disadvantaged preschool boys: Strategies, antecedents, and the development of self-control. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:222–35. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stansbury K, Zimmerman LK. Relations among child language skills, maternal socialization of emotion regulation, and child behavior problems. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1999;30:121–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1021954402840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson SL, Schilling EM, Bates JE. Measurement of impulsivity: Construct coherence, longitudinal stability, and relationship with externalizing problems in middle childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999;27:151–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1021915615677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osterlaan J, Sergeant JA. Inhibition in ADHD, aggressive, and anxious children: A biologically based model of child psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24:19–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01448371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Arousal, affect and attention as components of temperament. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:958–66. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochanska G, Coy KC, Tjebkes TL, Husarek SJ. Individual differences in emotionality in infancy. Child Dev. 1998;69:375–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothbart MK, Ziaie H, O’Boyle CG. Self regulation and emotion in infancy. New Dir Child Dev. 1992:7–23. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219925503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasey MW, el-Hag N, Daleiden EL. Anxiety and the processing of emotionally threatening stimuli: Distinctive patterns of selective attention among high and low-test-anxious children. Child Dev. 1996;67:1173–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto D, Hirayama S, Le Roux J. Psychological skills related to intercultural adjustment. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Nakagawa S. Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:925–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekman P, Friesen WV. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;17:124–9. doi: 10.1037/h0030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diener ML, Lucas RE. Adults’ desires for children's emotions across 48 countries: Associations with individual and national characteristics. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2004;35:525–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofstede G. London: McGraw-Hill; 1991. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnow S, Arens EA, Balkir N. Emotion regulation and psychopathology taking cultural influences into account. Psychotherapie in Psychiatrie, Psychotherapeutischer Medizin und Klinischer Psychologie. 2011;16:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler EA, Lee TL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotional suppression culture-specific? Emotion. 2007;7:30–48. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and wellbeing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:348–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeman J, Shipman K, Penza-Clyve S. Development and initial validation of the children's sadness management scale. J Nonverbal Behav. 2001;25:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and depression. Pers Individ Diff. 2001;30:1311–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Manual for the use of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Leiden University. Div Clin Health Psychol. 2002;24:1201–21. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achenbach TM. The Child Behavior Profile: I. Boys aged 6-11. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:478–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor SE, Sherman DK, Kim HS, Jacho J, Takagi K, Dunagan MS. Culture and social support: Who seeks it and why? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87:354–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trommsdorff G, Friedlmeier W, Mayer B. Sympathy, distress, and prosaically behavior of preschool children in four cultures. Int J Behav Dev. 2007;31:284–93. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X, Hastings PD, Rubin KH, Chen H, Cen G, Stewet SL. Child-rearing attitudes and behavioral inhibition in Chinese and Canadian toddlers: A cross-cultural study. Dev Psychol. 1998;34:677–86. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu X, Auerbach R, Yao S, Abela JR, Tong X. Psychometric properties of the cognition emotion regulation questionnaire: Chinese version. Cognition and Emotion. 2008;22:288–307. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young G, Zeman J. Tampa, FL: Poster presented at society for research in child development; 2003. Emotional expression management and social acceptance in childhood. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A Tran's diagnostic examination. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:974–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweitzer S. Emotion regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta–analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:217–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behaviors. Child Dev. 2003;74:1869–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sim L, Zeman J. The contribution of emotion regulation to body disses satisfaction and disordered eating in early adolescent girls. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:207–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suveg C, Zeman J. Emotion regulation in children with anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:750–9. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J Pers. 2004;72:1301–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsumoto D, Kupperbusch C. Idiot centric and all centric differences in emotional expression and experience. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2001;4:113–31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradley SJ. New York: Guilford; 2000. Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hourigan SE, Goodman KL, Southam-Gerow MA. Discrepancies in parents’ and children's reports of child. J Exp Child Psychol. 2011;110:198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jermann F, Van-Der-Linden M, d’Acremont M, Zermatten A. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ): Confirmatory factor analysis and psychometric properties of the french translation. Eur J Psycho Assess. 2006;22:126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraaij V, Van Derv Veek SM, Garnefski N, Schroevers M, Witlox R, Maes S. Coping, goal adjustment and psychological well-being in HIV infected men who have sex with men. Aids Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:395–402. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:1659–69. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Legerstee JS, Garnefski N, Jellesma FC, Verhulst FC, Utens EM. Cognitive coping in childhood anxiety disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:143–50. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ehring T, Fischer S, Schnülle J, Bösterling A, Tuschen-Caffier B. Characteristics of emotion regulation in recovered depressed versus never depressed individuals. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44:1574–84. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yousefi Z, Bahrami F, Mehrabi HA. Rumination: Beginning and continuous of depression. J Behav Sci. 2008;2:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Fontaine J. Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relation between emotional display rules and Individualism versus collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39:55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achenbach T. M. Multicultural Evidence-Based Assessment of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2010;47:707. doi: 10.1177/1363461510382590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]