Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction associated with vitamin D deficiency has been linked to many chronic vascular diseases. Vitamin D elicits its bioactive actions by binding to its receptor, vitamin D receptor (VDR), on target cells and organs. In the present study, we investigated the role of VDR in response to 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulation and oxidative stress challenge in endothelial cells. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 not only induced a dose- and time-dependent increase in VDR expression, but also induced up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (Flt-1 and KDR), as well as antioxidant CuZn-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) expression in endothelial cells. We demonstrated that inhibition of VDR by VDR siRNA blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased VEGF and KDR expression and prevented 1,25(OH)2D3 induced endothelial proliferation/migration. Using CoCl2, a hypoxic mimicking agent, we found that hypoxia/oxidative stress not only reduced CuZn-SOD expression, but also down-regulated VDR expression in endothelial cells, which could be prevented by addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 in culture. These findings are important indicating that VDR expression is inducible in endothelial cells and oxidative stress down-regulates VDR expression in endothelial cells. We conclude that sufficient vitamin D levels and proper VDR expression are fundamental for angiogenic and oxidative defense function in endothelial cells.

Keywords: VDR, angiogenic property, CuZn-SOD, oxidative stress, endothelial cells

1. Introduction

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3) induces biological effects by binding to its receptor, vitamin D receptor (VDR), on target cells and organs. VDR was first discovered and cloned in chick intestine [1,2] and later demonstrated to be present in almost all human cells and tissues [3]. The finding of VDR has broadened the scope of biological effects of vitamin D in human health. It is now widely accepted that bioactive vitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) and 1,25(OH)2D3, not only regulate bone and mineral metabolism, but also play important roles in cell proliferation/differentiation, organ development, and exert beneficial effects on cardiovascular, renal, and immune systems, etc. Whereas, vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency has been found to contribute to many none-bone related chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndromes, cancers, and autoimmune disorders [4–6]. Moreover, maternal vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency during pregnancy has also been found to be associated with preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia. [7,8].

Identification of VDR in cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells leads the early interests of vitamin D in the cardiovascular system [9 10]. It has now been demonstrated, that vitamin D exerts profound effects on cardiovascular system such as anti-inflammation, anti-atherosclerosis, and direct cardio-protective actions. All of these vitamin D beneficial effects are mediated by VDR. For example, in cardiomyocytes 1,25(OH)2D3 induced VDR activation resulted in cardiomyocyte relaxation through modulation of calcium flux, thereby improves diastolic function of the heart [11]. The important protective role of VDR in heart was also demonstrated by VDR- knockout mice, in which mice with VDR-knockout in cardiomyocytes developed cardiac hypertrophy, indicating that vitamin D-VDR signaling system possesses direct, anti-hypertrophic activity in the heart [12].

In the study of vitamin D metabolic system in the human placenta, we found that VDR was extensively expressed in placental trophoblasts from normotensive pregnancies [13]. However, VDR expression was barely detectable in placental villous core vessel endothelium [13]. Although studies have shown that VDR was expressed in endothelial progenitor cells isolated from systemic and cord blood [14,15], effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on VDR expression and downstream of VDR activation in vascular endothelium are largely unknown. Thus, in the present study we investigated the role of VDR in angiogenic and oxidative defense function in endothelial cell. We examined effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on VDR, as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and CuZn-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD), expression in endothelial cells. VEGF is a key angiogenic factor and CuZn-SOD is the first line of antioxidant defense enzyme to dismutate superoxide radicals in living cells. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 not only induced dose-dependent and time-dependent increases in VDR expression, but also induced up-regulation of VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression in endothelial cells. We further found that inhibition of VDR expression by VDR siRNA blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression. These results suggest that vitamin D levels are critical to modulate endothelial VDR expression and VDR activation, and subsequently regulate angiogenic and oxidative defense function in endothelial cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

1,25(OH)2D3 was purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Endothelial cell growth medium (EGM) was from Lonza Walkersville, Inc. (Walkersville, MD). Antibodies for VDR (D-6, sc-13133), VEGF (A-20, sc-152), Flt-1 (H-225, sc-9029), KDR (A-3, sc-6251), and Mn-SOD (A-2, sc-133134) were purchased from Santa Cruz (San Diego, CA). Antibody for CuZn-SOD (N-19, ab52950) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and for HO-1 (BD610713) was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). β-actin antibody was from Sigma Chemicals. VDR siRNA (ON-TARGET plus siRNA, J-003448-07) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) and scrambled siRNA (sc-37007) was purchased from Santa Cruz. MTT assay kit was from Roche Diagnostics Corporation (Indianapolis, IN). All other chemicals and reagents were from Sigma Chemicals unless otherwise noted.

2.2. Endothelial cell isolation and culture

Umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used in this study. HUVECs were isolated by collagenase digestion as previously described [16]. Collection of placental umbilical cord for HUVEC isolation was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center - Shreveport (LSUHSC-S), LA. A total of 16 placental cords were used for this study. All placentas were from normal term deliveries with maternal blood pressure < 140/90mmHg without obstetrical and medical complications. None of the patients had signs of infection, nor were they smokers. Isolated endothelial cells were incubated with EGM containing recombinant human epithelial growth factor (rhEGF), hydrocortisone, gentamicin sulfate/amphotercin-B, bovine brain extract, and 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Passage 2–3 cells were used in the experiments.

2.3. Protein expression

Expression for VDR, VEGF, Flt-1, KDR, CuZn-SOD, Mn-SOD, and HO-1 were examined by Western blot. Total cellular protein was extracted using ice-cold protein lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris, 0.5% NP40, 0.5% Triton X-100 with protease inhibitors (PMSF, DTT, leupeptein, and aprotinin), and protein phosphatase inhibitors. An aliquot of 10μg total protein per sample was subject for electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membranes were probed with a specific antibody and followed by a matched secondary antibody. The bound antibody was visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescent (ECL) detection Kit (Amersham Corp, Arlington Heights, IL) and exposed onto x-ray film. The membranes were stripped, blocked, and then re-probed with β-actin antibody (used as loading control for each sample). The density was scanned and analyzed by Quantity One Imaging analysis software (Bio-Rad). Relative protein expression for VDR, VEGF, Flt-1, KDR, CuZn-SOD, Mn-SOD, and HO-1 was normalized by β-actin expression for each sample.

2.4. VDR siRNA transfection assay

Transfection assay was conducted using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, when cells reached about 70% confluence, cells were starved with 1ml of serum free endothelial basal medium for 2 hours and then incubated with Opti-MEM I medium for 6 hours, which contains 50 nM VDR siRNA mixed with Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX transfection agent. Cells transfected with scrambled siRNA were used as control. To test siRNA blocking effect, 1,25(OH)2D3 was added to the culture 40 hours after transfection. Cellular protein was collected 24 hours after additon of 1,25(OH)2D3 and protein expression was then determined by Western blot.

2.5. MTT assay

1,25(OH)2D3 induced cell proliferation was determined using the 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. MTT assay was performed according to the manufacutrer’s instruction. Briefly, endothelial cells (5×103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated with EGM overnight. Cells were then treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 at concentrations of 0, 5, 20, and 100nM for 24 hours. An aliquot of 100μl of 0.5 mg/ml MTT was then added to each well. Solubilization was carried out by 10% SDS and plates were read with a spectrophotometer. Data was expressed as fold change in treated cells compared to untreated controls.

2.6. Wound healing assay

Cell migration was determined by wound healing assay. Briefly, cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well. VDR siRNA transfection was performed when cells grew to 70% confluence. Mechanical endothelial damage was created by scratching when cells grew to confluence using a sterile 200μl tip. After scratching, cells were washed twice with endothelial basal medium to remove cell debris. The scratches were then photographed using SpotInsight color camera linked to an Olympus microscope (Olympus CK40, Japan). For photographing, three randomly selected fields were marked in each well and then images were captured and recorded to a PC computer. 1,25(OH) 2D3 at a concentration of 20nM was then added to designated wells and cells were cultured with serum free EGM for 24 hrs. The fields were rephotographed 24h after scratching. Cell migration was analyzed using NIH Image J software. The distance between the scratching line (wound edges) was set as 100%. Cell migration was determined by measuring the distance between the edge of migrated cells within the scratching line and calculated as percentage of migration.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Paired t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for statistical analysis by computer software Statview (Cary, NC). Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for post-hoc test. A probability level of less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

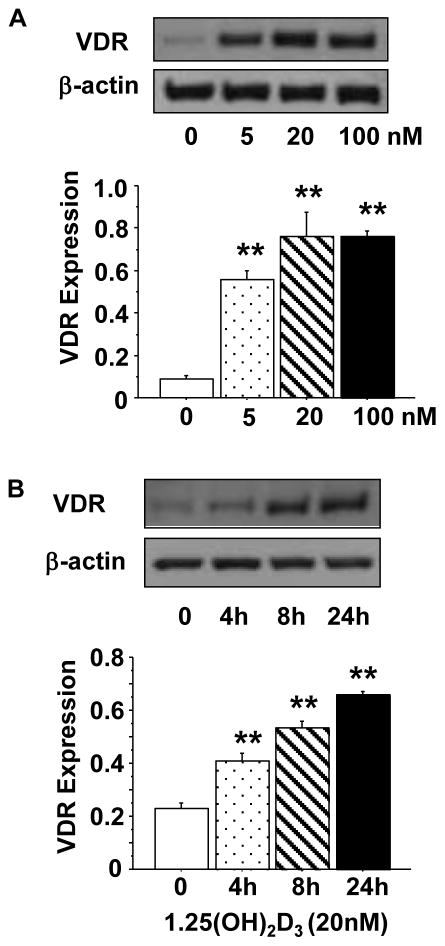

3.1. VDR expression is inducible in endothelial cells

To test effects of vitamin D on endothelial cells, we first examined dose-response of VDR expression in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. Cells were cultured with 1,25(OH)2D3 at concentrations of 0, 5, 20, and 100nM for 24 hours. The concentrations used in this experiment are consistent with previous published works [17–19]. Our results showed that VDR was weakly expressed in untreated cells and its expression was significantly up-regulated in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. As shown in Figure 1A, 1,25(OH)2D3 induced a dose dependent increase in VDR expression at 5 and 20nM (Figure 1A). Using the 20nM concentration, we then examined if 1,25(OH)2D3 induced VDR expression was time-dependent. Cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0, 4, 8, and 24 hours. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR protein expression was also time-dependent (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR protein expression in endothelial cells. A: Cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 at concentrations of 0, 5, 20, and 100nM for 24 hours. 1,25(OH)2D3 induced a dose-dependent increase in VDR expression. B: Cells were treated with 20nM of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0, 4, 8, and 24 hours. 1,25(OH)2D3 induced a time-dependent increase in VDR expression. The bar graphs show the mean ± SE of relative VDR expression after normalized with β-actin expression in each sample, **p<0.01: treated vs. controls. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

To determine the specificity of VDR up-regulation induced by 1,25(OH)2D3, VDR siRNA was used. We found that VDR siRNA blocked VDR up-regulation induced by 1,25(OH)2D3, whereas scrambled siRNA had no effect (Figure 1 supplement). 1,25(OH)2D3 induced VDR up-regulation was further determined by pretreatment of endothelial cells with actinomysin D and cycloheximide. Actinomycin D has the ability to inhibit transcription and cycloheximide is an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis in eukaryotic organisms. Our results showed that both actinomysin D and cycloheximide could inhibit 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased VDR expression (Figure 2 supplement). Taken together, these results demonstrate that expression of VDR in endothelial cells is inducible and 1,25(OH)2D3 induced VDR expression is regulated through both transcriptional and translational mechanisms.

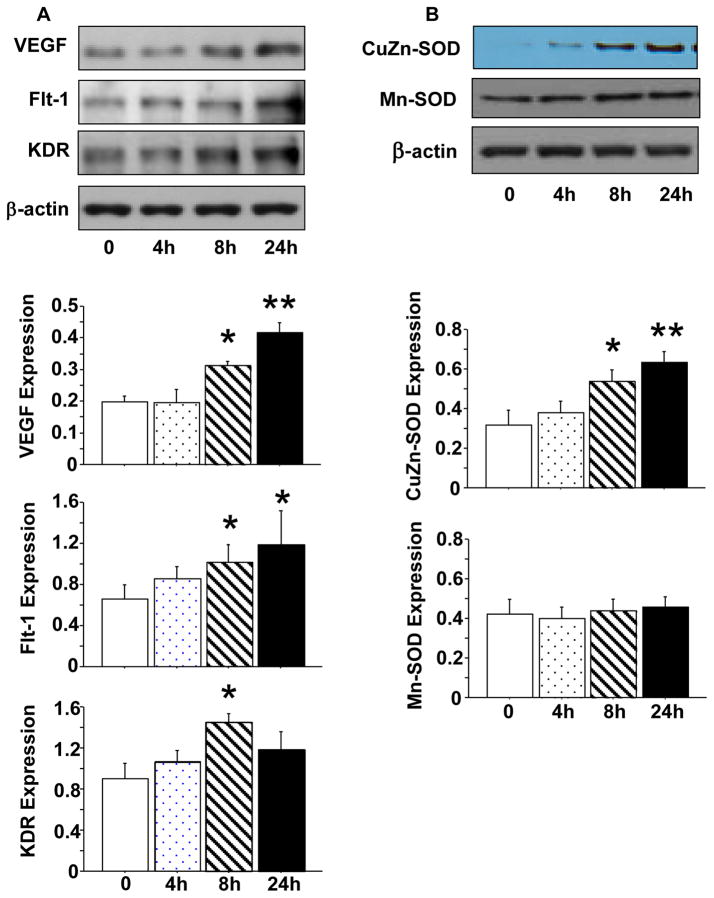

3.2. Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression in endothelial cells

Grundmann et al reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 could improve angiogenic properties of endothelial progenitor cells isolated from cord blood by increasing pro-MMP-2 activity and VEGF mRNA expression [14]. Endothelial progenitor cells have the ability to differentiate into endothelial cells. To determine if 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts similar effects on endothelial cells, we examined VEGF and its receptors Flt-1 and KDR expression. We also examined antioxidant enzyme CuZn-SOD and Mn-SOD expression in endothelial cells with or without exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3. Confluent endothelial cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 at a concentration of 20nM for 4, 8, and 24 hrs. Results are shown in Figure 2. We found that increased VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression was time-dependent in cells cultured with 1,25(OH)2D3, p<0.01 (Figure 2A and B). Flt-1 and KDR expression were also significantly increased, p<0.05, but expression of Mn-SOD was not affected in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3, Figure 2A and B.

Figure 2.

Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on protein expression of VEGF, Flt-1, KDR, CuZn-SOD, and Mn-SOD in endothelial cells. A: Protein expression of VEGF, Flt-1, and KDR in endothelial cells treated with 20nM of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0, 4, 8, and 24 hours. B: Protein expression of CuZn-SOD and Mn-SOD in endothelial cells treated with 20nM of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 0, 4, 8, and 24 hours. The bar graphs show relative target protein expression after normalized with β-actin expression in each sample, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 vs. not. Data are expressed as mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

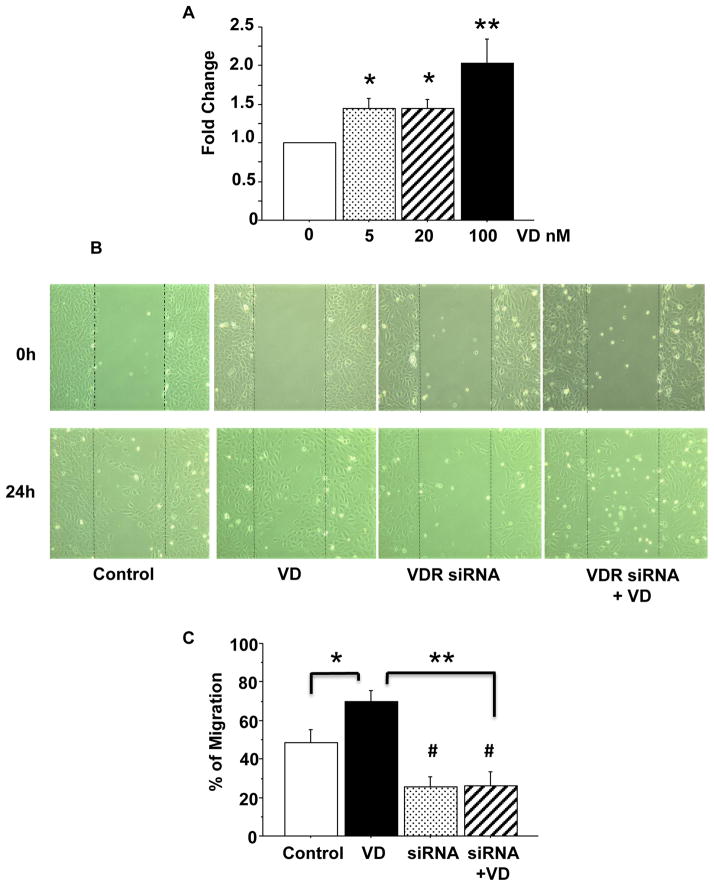

3.3. 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes endothelial proliferation

VEGF is an important angiogenic factor. The phenomenon of up-regulation of VEGF and KDR expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 indicates that 1,25(OH)2D3 could promote endothelial proliferation. To test this, cells were incubated with different concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours and then MTT assay was performed. As we expected, 1,25(OH)2D3 induced a dose dependent increase in purple formazan formation, indicating that 1,25(OH)2D3 promotes endothelial cell proliferation, Figure 3A.

Figure 3.

1,25(OH)2D3 induced cell proliferation and migration. A: 1,25(OH)2D3 induced endothelial proliferation was determined by MTT assay. Cells were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 (VD) at concentrations of 0, 5, 20, 100nM for 24 hours (n=6). 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased cell proliferation was dose-dependent, *p<0.05, and **p<0.01. B: Representative images of 1,25(OH)2D3 induced cell migration (wound healing assay). Images were taken immediately after scratching (0 hour) and 24 hours after addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 in culture. C: Bar graph shows quantitative measure of cell migration. Data are expressed as mean ± SE of wound healing assay from 3 independent experiments. VD: 1,25(OH)2D3; *p<0.05: VD treated vs. untreated control; # p<0.05: VDR siRNA vs. untreated control; and **p<0.01: VDR siRNA or VDR siRNA + VD vs. VD, respectively.

3.4. VDR mediates 1,25(OH)2D3 induced endothelial migration

Wound-healing assay was performed to evaluate VDR-mediated endothelial migration. Results were shown in Figure 3B and C. Figure 3B shows representative images of endothelial cells immediately after scratching and 24 hours after addition of 1,25(OH)2D3. The bar graph (Figure 3C) showed the mean of percentage of cell migration in control cells, cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3, cells treated with VDR siRNA, and VDR siRNA+1,25(OH)2D3. These results were means from 3 independent experiments. Our results clearly showed that cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 displayed an increase in endothelial migration compared to control cells, p<0.05. VDR siRNA decreased cell migration (compared to control cells), p<0.05 and blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced endothelial migration, p<0.01.

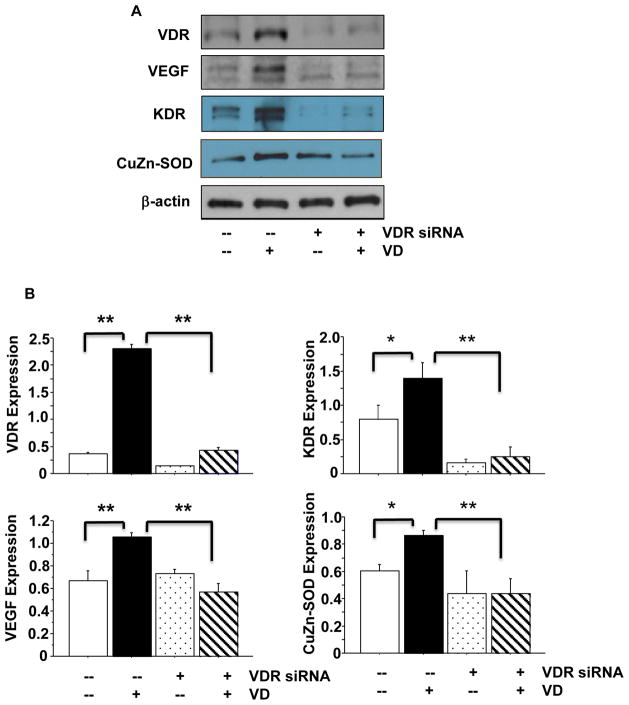

After wound healing assay, cells were collected and protein expression for VDR, VEGF, Flt-1, and KDR were determined. Consistent with wound healing assay results, we found that VDR siRNA not only blocked VDR expression but also blocked increased VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD expression that were induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 4). VDR siRNA had no effect on Flt-1 expression (data not show). The bar graph showed relative VDR, VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD expression after normalized by β-actin expression for each sample from 3 independent experiments, Figure 4B. These data provide further evidence that increased VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 is mediated by VDR in endothelial cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of VDR inhibition on VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD protein expression. VDR siRNA was used to inhibit VDR expression. VDR siRNA not only inhibited 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased VDR expression, but also blocks 1,25(OH)2D3 induced VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD up-regulation, in endothelial cells. A: VDR, VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD expression in control cells, cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3, and cells transfected with VDR siRNA with or without addition of 1,25(OH)2D3. B: Relative VDR, VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD expression normalized with β-actin expression, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. These results indicate that VDR modulates VEGF, KDR, and CuZn-SOD expression in endothelial cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments. VD: 1,25(OH)2D3.

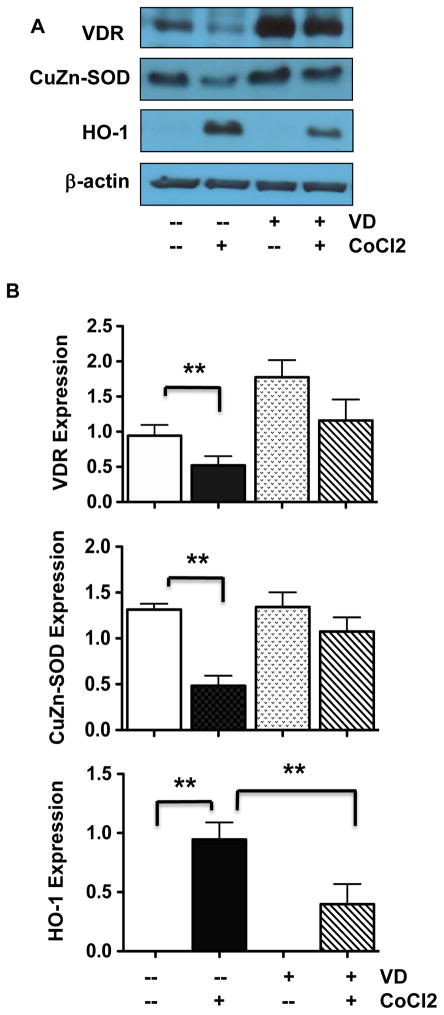

3.5. VDR activation reduces oxidative stress in endothelial cells

Superoxide dismutase catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide and this is an important antioxidant defense mechanism in all cells exposed to oxygen. The cytosols of all eukaryotic cells contain CuZn-SOD. The finding of increased CuZn-SOD expression along with increased VDR expression induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 2) suggests that VDR activation or expression could be affected by oxidative stress. To test this, endothelial oxidative stress was induced by treating cells with CoCl2 at 250μM for 24 hours in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. CoCl2 is a hypoxic mimetic agent that has been widely used to induce oxidative stress in various in vitro cell and tissue culture studies [13,20,21]. Endothelial expression of VDR, CuZn-SOD, and home oxygenase-1 (HO-1) were then determined. HO-1 is a sensor of cellular oxidative stress. Interestingly, we found that down-regulation of VDR and CuZn-SOD expression was correlated with up-regulation of HO-1 in endothelial cells induced by CoCl2 (Figure 5). These CoCl2-induced effects could be blocked or reduced by pretreatment of the cells with 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of oxidative stress on VDR, CuZn-SOD, and HO-1 protein expression. A: Representative blots for VDR, CuZn-SOD, and HO-1 expression in cells treated with CoCl2 in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 in culture. B: Relative protein expression for VDR, CuZn-SOD, and HO-1 after normalized with β-actin expression in each sample, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of VDR activation associated with endothelial angiogenic property and response to oxidative stress. We found that 1,25(OH)2D3 induced a dose- and time-dependent increase in VDR expression in endothelial cells. We also found that 1,25(OH)2D3 induced an increase in VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression in endothelial cells. These findings are important, suggesting that if in an in vivo situation, vascular endothelial VDR expression/function likely depends on the bioactive vitamin D levels in the circulation, i.e. circulating 1,25(OH)2D3 levels may determine the level of VDR expression and possibly its downstream biological functions in the vasculature.

To study VDR mediated endothelial angiogenic property, we examined VEGF and its receptors Flt-1 and KDR expression. We also determined cell proliferation and migration by MTT assay and wound healing assay. Our results showed that similar to VDR, protein expression for VEGF, Flt-1, and KDR were all increased in cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. These results are in line with the work conducted by Grundmann et al [14], in which they studied effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on endothelial progenitor cells that were isolated from cord blood and found that 1,25(OH)2D3 could improve angiogenic properties of endothelial progenitor cells by increasing pro-MMP-2 activity and VEGF mRNA expression [14]. Endothelial progenitor cells have the ability to differentiate into endothelial cells. In our study, we found that 1,25(OH)2D3 not only induced VEGF, but also Flt-1 and KDR, expression in endothelial cells. The specificity of VDR mediated endothelial angiogenic property was further demonstrated by the VDR siRNA experiments. We found that inhibition of VDR by VDR siRNA not only prevented 1,25(OH)2D3-induced cell migration, but also blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased VDR and VEGF expression. Taken together, these results indicate that bioactive vitamin D has the ability to improve angiogenic property not only in endothelial progenitor cells [14], but also in endothelial cells as demonstrated in our study.

Up-regulation of CuZn-SOD expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 is another significant finding in our study. CuZn-SOD is one of the critical antioxidant enzymes to dismutate superoxide radicals in living cells. Although the exact mechanism of CuZn-SOD up-regulation by 1,25(OH)2D3 is not known, the finding of VDR inhibition by VDR siRNA blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced increased CuZn-SOD expression provided convincing evidence of the association between VDR and CuZn-SOD in endothelial cells. This finding also suggests the importance of VDR expression/activation associated with increased antioxidant activity, or vise versa, in the vasculature. In fact, several animal studies did show a close relationship of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency with increased oxidative stress in the cardiovascular system. For example, Argacha et al found that animals with vitamin D-deficient diet developed hypertension and resulted in an increase in superoxide anion production in the aortic wall [22]. A study conducted by Weng et al also found that vitamin D-deficient diet in LDL receptor-null and ApoE-null mice not only developed hypertension but also exhibited accelerated atherosclerosis [23] and the vitamin D-deficient diet induced hypertension could be reversed by returning chow-fed vitamin D-deficient diet to vitamin D-sufficient chow diet [23]. Their data suggest that vitamin D-deficiency induced harmful outcomes on the cardiovascular system could be reversed by vitamin D supplement. The finding that vitamin D supplement reduced deposition of advanced glycation end-products in the aortic wall in diabetic rats [24] further supports the idea that vitamin D exerts anti-oxidative effects on the cardiovascular system.

We believed that vitamin D-deficiency associated with increased oxidative stress could be linked to aberrant VDR expression or inactivation. Previously, we found that oxidative stress could down-regulate VDR expression in placental trophoblasts [13]. To test if oxidative stress affects VDR expression in endothelial cells, CoCl2 was applied to the cell culture. CoCl2 is a hypoxic mimicking agent and has been used to induce oxidative stress in numerous in vitro studies [20,21,25]. Our results showed that VDR expression was significantly down-regulated in, cells treated with CoCl2. Down-regulation of VDR expression in endothelial cells by increased oxidative stress was also confirmed by increased HO-1 expression. Interestingly, this oxidative stress induced down-regulation of VDR expression could be prevented by pretreatment of endothelial cells with 1,25(OH)2D3. These results suggest: 1) VDR is sensitive to oxidative stress, and 2) sufficient vitamin D could protect VDR from oxidative stress insults. These data provide further evidence that sufficient circulating vitamin D levels are beneficial for vascular endothelium against oxidative insult.

One concern is that the concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 used in our study was probably higher than the physiological levels. However, the concentrations used in our study were similar to what was used in previously published works [17–19]. For example, an in vitro C3H10T(1/2) mouse fibroblast culture study showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 at doses of 5–100nM promoted VEGF promoter expression in a dose-dependent manner [17]. The same doses (5–100nM) of 1,25(OH)2D3 was also found to stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [18]. In a T-lymphocyte culture study, 1,25(OH)2D3 at a concentration of 100nM could suppress IL-17A production stimulated by TNFα [19]. Thus, we believe that results obtained from this study are valid.

In this study, we did not examine biosynthesis of vitamin D in endothelial cells. However, the presence of 25-hydroxylase (CYP2R1) and 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) in endothelial cells [13] and the evidence of endothelial synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 [26], together with our finding of inducible VDR expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 in endothelial cells suggest that endothelial cells may have a vitamin D biosynthesis and/or auto-regulatory system, which warrant further investigation.

It has now been recognized that vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency is a global health problem and likely to be a risk factor for a wide spectrum of acute and chronic illnesses, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, infectious and autoimmune disorders, and cancers, etc. [27]. It is also known that endothelial dysfunction associated with increased oxidative stress, increased inflammatory response, and altered angiogenic activity is a characteristic of many chronic cardiovascular diseases. Although the precise action of vitamin D on endothelial function is largely unknown, based on beneficial effects of vitamin D on endothelial cells, such as anti-inflammatory response by inhibition of cytokine and adhesion molecule production [28], anti-oxidative activity by attenuation of advanced glycation end products [29], and the ability to promote endothelial NO production [30] and increase in VEGF [14] and CuZn-SOD expression, there is no doubt that vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and aberrant VDR expression contributes to endothelial dysfunction. Thus, it is plausible to speculate that sufficient vitamin D levels and proper VDR expression are fundamental for endothelial health. Further study on cellular and molecular regulation of VDR and its downstream actions shall provide valuable information of vitamin D on endothelial and vascular biology and beyond.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1 supplement. VDR protein expression in endothelial cells. VDR siRNA, but not scramble siRNA, blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR expression in endothelial cells.

Figure 2 supplement. Effects of actinomycin D and cycloheximide on VDR protein expression. Both actinomycin D (5μg/ml) and cycloheximide (5μg/ml) blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR expression in endothelial cells.

Highlights.

VDR expression is inducible in endothelial cells (EC).

Oxidative stress down-regulates VDR expression.

Inhibition of VDR reduces VEGF and CuZn-SOD expression.

1,25(OH)2D3 promotes EC angiogenic and anti-oxidative activity in EC.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the 60th Annual Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, Orlando, FL, March 20–23, 2013 and supported in part by grants from NIH, NHLBI HL65997 to YW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brumbaugh PF, Haussler MR. Specific binding of 1α,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol to nuclear components of chick intestine. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1588–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonnell DP, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pike JW, Haussler MR, O’Malley BW. Molecular cloning of complementary DNA encoding the avian receptor for vitamin D. Science. 1987;235:1214–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.3029866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, Luderer HF, Lieben L, Mathieu C, Demay M. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:726–776. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motiwala SR, Wang TJ. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:345–353. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283474985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad AB, Alappat L, Valerio M. Vitamin D and metabolic syndrome risk factors: evidence and mechanisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52:103–112. doi: 10.1080/10408391003785458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleet JC, DeSmet M, Johnson R, Li Y. Vitamin D and cancer: a review of molecular mechanisms. Biochem J. 2012;441:61–76. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urrutia RP, Thorp JM. Vitamin D in pregnancy: current concepts. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:57–64. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283505ab3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brannon PM. Vitamin D and adverse pregnancy outcomes: beyond bone health and growth. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:205–12. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111003399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walters MR, Wicker DC, Riggle PC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors identified in the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1986;18:67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(86)80983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merke J, Hofmann W, Goldschmidt D, Ritz E. Demonstration of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 receptors and actions in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987;41:112–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02555253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pil S, Tomaschitz A, Drechsler C, Dekker JM, März W. Vitamin D deficiency and myocardial diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:1103–1113. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S, Law CS, Grigsby CL, Olsen K, Hong TT, Zhang Y, Yeghiazarians Y, Gardner DG. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of the vitamin D receptor gene results in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2011;124:1838–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma R, Gu Y, Zhao S, Sun J, Groome LJ, Wang Y. Expressions of vitamin D metabolic components VDBP, CYP2R1, CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and VDR in placentas from normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E928–935. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00279.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundmann M, Haidar M, Placzko S, Niendorf R, Darashchonak N, Hubel CA, von Versen-Hoynck F. Vitamin D improves the angiogenic properties of endothelial progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C954–962. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00030.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cianciolo G, La Manna G, Cappuccilli ML, Lanci N, Della Bella E, Cuna V, Dormi A, Todeschini P, Donati G, Alviano F, Costa R, Bagnara GP, Stefoni S. VDR expression on circulating endothelial progenitor cells in dialysis patients is modulated by 25(OH)D serum levels and calcitriol therapy. Blood Purif. 2011;32:161–173. doi: 10.1159/000325459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Adair CD, Coe L, Weeks JW, Lewis DF, Alexander JS. Activation of endothelial cells in preeclampsia: Increased neutrophil-endothelial adhesion correlates with up-regulation of adhesion molecule P-selectin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells isolated from preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1998;5:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(98)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine MJ, Teegarden D. 1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in C3H10T1/2 mouse embryo fibroblasts. J Nutr. 2004;134:2244–2250. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardús A, Parisi E, Gallego C, Aldea M, Fernández E, Valdivielso JM. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through a VEGF-mediated pathway. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1377–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Hamburg JP, Asmawidjaja PS, Davelaar N, Mus AM, Cornelissen F, van Leeuwen JP, Hazes JM, Dolhain RJ, Bakx PA, Colin EM, Lubberts E. TNF blockade requires 1,25(OH)2D3 to control human Th17-mediated synovial inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:606–612. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen JK, Zhan YJ, Yang CS, Tzeng SF. Oxidative stress-induced attenuation of thrombospondin-1 expression in primary rat astrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:59–70. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamiya T, Hara H, Inagaki N, Adachi T. The effect of hypoxia mimetic cobalt chloride on the expression of EC-SOD in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Redox Rep. 2010;15:131–134. doi: 10.1179/174329210X12650506623483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argacha JF, Egrise D, Pochet S, Fontaine D, Lefort A, Libert F, Goldman S, van de Borne P, Berkenboom G, Moreno-Reyes R. Vitamin D deficiency-induced hypertension is associated with vascular oxidative stress and altered heart gene expression. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;58:65–71. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31821c832f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng S, Sprague JE, Oh J, Riek AE, Chin K, Garcia M, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Vitamin D deficiency induces high blood pressure and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salum E, Kals J, Kampus P, Salum T, Zilmer K, Aunapuu M, Arend A, Eha J, Zilmer M. Vitamin D reduces deposition of advanced glycation end-products in the aortic wall and systemic oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg MA, Schneider TJ. Similarities between the oxygen-sensing mechanisms regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and erythropoietin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4355–4359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merke J, Milde P, Lewicka S, Hügel U, Klaus G, Mangelsdorf DJ, Haussler MR, Rauterberg EW, Ritz E. Identification and regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor activity and biosynthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Studies in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and human dermal capillaries. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1903–1915. doi: 10.1172/JCI114097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, Wagner CL, Hollis SW, Grant WB, Shoenfeld Y, Lerchbaum E, Llewellyn DJ, Kienreich K, Soni M. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-A review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo K, Hasegawa S, Suzuki Y, Hirano R, Wakiguchi H, Kittaka S, Ichiyama T. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) inhibits vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and interleukin-8 production in human coronary arterial endothelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;132:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talmor Y, Golan E, Benchetrit S, Bernheim J, Klein O, Green J, Rashid G. Calcitriol blunts the deleterious impact of advanced glycation end products on endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1059–1064. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00051.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molinari C, Uberti F, Grossini E, Vacca G, Carda S, Invernizzi M, Cisari C. 1α,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol induces nitric oxide production in cultured endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27:661–668. doi: 10.1159/000330075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1 supplement. VDR protein expression in endothelial cells. VDR siRNA, but not scramble siRNA, blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR expression in endothelial cells.

Figure 2 supplement. Effects of actinomycin D and cycloheximide on VDR protein expression. Both actinomycin D (5μg/ml) and cycloheximide (5μg/ml) blocked 1,25(OH)2D3 induced up-regulation of VDR expression in endothelial cells.