Abstract

Chaetoglobosin K (ChK) is a natural product that inhibits anchorage-dependent and anchorage-independent growth of ras-transformed cells, prevents tumor-promoter disruption of cell-cell communication, and reduces Akt activation in tumorigenic cells. This report demonstrates how ChK modulates the JNK pathway in ras-transformed and human lung carcinoma cells and investigates regulatory mechanisms controlling ChK’s dual effect on the Akt and JNK signaling pathways. Human lung carcinoma and ras-transformed epithelial cell lines treated with ChK or vehicle for varying times were assayed for cell growth or extracted for total proteins for western blot analysis using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies to monitor changes in activation of JNK, Akt, and other signaling enzymes. Results show that ChK inhibited both Akt and JNK phosphorylation at key activation sites in ras-transformed cells as well as human lung carcinoma cells. Downstream effectors of both kinases were accordingly affected. Direct upstream kinases of JNK were not affected by ChK. Wortmannin and LY294002, two PI3 kinase inhibitors, inhibited Akt but not JNK phosphorylation in ras-transformed cells. This study demonstrates the dual inhibitory effect of ChK on both the Akt and JNK signaling pathways in ras-transformed epithelial and human carcinoma cells. The unique dual effect of ChK on these key pathways involved in carcinogenesis earmarks ChK for further studies to determine its molecular target(s) and in vivo anti-tumor potential.

Keywords: Chaetoglobosin K, JNK, Akt kinase, Wortmannin, LY294002

INTRODUCTION

There have been many challenges in creating effective therapies to inhibit growth of cancer cells, in part because of a lack of selectivity between dividing normal and cancer cells. Persistent activation of cellular signaling pathways by oncogenes results in disruption of normal growth control and can lead to neoplastic transformation. Targeted anti-tumor therapy is based on the hypothesis that inhibition of these constitutively turned on key signaling pathways will control tumor cell growth by altering the phenotype of the particular tumor cell, while minimizing effects on cells in which these signaling pathways are not dominant. This hypothesis is supported by numerous tumor cell model systems in which inhibition of oncogenic signaling pathways reduces cell growth, decreases tumorigenicity of treated cells, and at least partially reverses the transformed phenotype. Examples include inhibition of src, ras neu, and myc, mdm2 oncogene signaling pathways, among others [1–4]. While substantial progress has been made in developing drugs that target overactive oncogenic pathways, current therapies are often limited to one or a few types of cancer and most have limited effectiveness in extending survival times [5–12]. Thus, additional therapies are needed to target other cancer types and with greater effectiveness.

The Ras-activated PI3 kinase (PI3K) pathway is an important regulator of cell proliferation and survival. When over stimulated, it has been shown to lead to neoplastic transformation [13–15]. An important downstream effector of PI3K is Akt (also called PKB), a PIP3- and phosphorylation-activated serine-threonine kinase that phosphorylates several intracellular targets involved in cell proliferation and survival such as GSK-3α, FKHD, and MDM2 [14, 16–18]. Activation of Akt/PKB has been reported to be frequently elevated in human cancers and constitutive activation of this kinase was required for oncogenic transformation in NIH 3T3 cells [19]. Elevated activation of Akt has also been linked to skin tumorigenesis [20, 21]. In addition, phosphorylation of Akt on serine 473 was shown to be increased in poorly differentiated prostate cancer cells [22] and phosphorylation on this residue is also a good predictor of poor clinical outcome in cancer patients [23]. Results from these and other studies contribute to Akt’s current status as a cancer biomarker and target for development of novel human cancer therapies.

The stress-activated protein kinase pathway, JNK, alternatively referred to as SAPK/JNK, also plays important roles in control of cell proliferation in a wide variety of cell types. Elevated JNK activation has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of human brain tumors [24]. Activated JNK may act as an oncoprotein through its abilities to activate the transcription factor component c-JUN, or inactivate the proapoptotic protein BAD [25]. More recently, Khatlani, et al. [26] showed that JNK is activated in a significant subset of non-small-cell lung carcinoma biopsies, and can promote neoplastic transformation in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Thus, reduced activation of JNK could be beneficial in controlling growth in tumors expressing over-activated JNK.

Chaetoglobosin K (ChK) is a bioactive natural product cytochalasin derived from Diplodia macrospora [27] that has been shown to promote apoptosis and inhibit cytokinesis in ras-transformed cells [28, 29] as well as prevent tumor promoter induced inhibition of gap junction-mediated cellular communication [30,31]. ChK was also shown to reduce Akt phosphorylation at two activaiton sites in ras-transformed cells [29]. We now demonstrate dual inhibition by ChK of both Akt and JNK activation in ras-transformed epithelial and human lung carcinoma cells. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate inhibition of both of these oncogenic signaling pathways by a single compound. This unique dual effect of ChK on these key signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis underscores its potential as a targeted tumor therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

WB-ras cells were derived from WB-F344 rat liver epithelial cells and were obtained from James Trosko at Michigan State University. H2009 and H1299 human lung tumor cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and provided by Randall Ruch at the University of Toledo and Nader Moniri at Mercer University, respectively. Chaetoglobosin K was purified from Diplodia macrospora at >97% pure [27] and provided by H. Cutler. Alpha Modification of Eagle’s Medium and RPMI-1640 were purchased from Mediatech (Herndon, VA). L-glutamine, trypsin, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS), were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). PBA, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), protease inhibitor cocktail, Trypan blue solution, Wortmannin, and Ponceau Red solution were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). JNK, Akt, PTEN, PDK1, MKK4, MKK7, c-JUN, ATF-2, and phospho-JNK (thr183/tyr185), phospho-Akt (ser473), phospho-PTEN (ser308/thr382,383), phospho-PDK1 (ser241), phospho–MKK4 (thr261), phospho-MKK7 (ser271/thr275), phospho-c-JUN (ser63), phospho-ATF2 (thr71), phospho-MDM2 (ser166), phospho-Stat3 (ser727), phospho-Rac1(ser71), β-actin, α-tubulin, anti-rabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies and LY294002 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Tween-20, TRIS-HCl, DC Protein Assay, SDS, nonfat dry milk, 25x alkaline phosphatase color development buffer, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT), protein molecular mass standards, PVDF membranes and all electrophoresis and transfer buffer components were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). All other chemicals, reagents, and solvents used were of analytical grade.

Methods

Cell Culture

Human lung carcinoma cells (H2009 or H1299) were grown in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 2mM/L L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum and used between passages 38–55 for H2009 and 5–10 for H1299. WB-ras rat liver epithelial cells were subcloned from single cells to obtain the WB-ras1 line, grown in alpha Modification of Eagle’s Media supplemented with 2 mM/L l-glutamine and 5% FBS, and used for experiments between passages 3 and 18. G418 antibiotic was added to the α-MEM for culturing cells at a concentration of 500 μM, but was not added to cells plated for experiments. Confluent cells were subcultured by trypsinization and plated at 5–20% confluence except where noted. Cells were incubated in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cell Growth Assay

H2009 human lung carcinoma cells or WB-ras1 cells were plated at 5–10% confluence onto 35mm2 dishes, initial plating densities quantified, culture medium added to 2 mL, and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were treated with varying concentrations of vehicle (DMSO) or ChK in DMSO and incubated at 37°C for varying times. The DMSO concentration was kept below 1%. Following the desired incubation time, medium was removed and cells were washed twice with PBS. 0.2 ml of 0.25% trypsin solution and 0.8 ml of PBS were added and cells incubated until they detached from the dish, followed by addition of 1 ml of PBS containing 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM MgCl2. Cells in suspension were counted as is or after dilution with 2–5 ml as needed of PBS, using a hemocytometer to determine the number of cells per dish. Triplicate or quadruplicate dishes were counted for each time point.

Protein Concentration Assay

Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay. BSA was used as a standard protein and absorbances were read at 750 nm using a Tecan plate reader.

Western Immunoblot Assay

Human lung carcinoma cells and WB-ras1 were grown to 85–95% confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, washed with 10 ml of PBS and extracted with 250 μl 2% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, and 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysed cells were scraped, suspensions transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, and samples sonicated for two, 15 second pulses at room temperature. 4x Laemmli sample buffer was added to equal amounts of protein/lane at 25% final sample volume, proteins separated on 12.0% acrylamide SDS gels, and transferred to PVDF membranes by wet transfer overnight at 20V or semi-dry transfer for 7 minutes using a Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo. Membranes were washed with H2O, stained with Ponceau Red for 2–3 minutes, washed with H2O, scanned, then blocked using 4% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Tween-20, 40 mM Tris, pH 7.5 for 1–2 hours. Specified primary antibodies were incubated separately with blots in block buffer for 24 hours at 4°C. Immunopositive bands were detected using alkaline phosphatase anti-rabbit secondary antibody and development with BCIP/NBT. Selected blots were reprobed by 1–2 second re-hydration in methanol, followed by a 30 minute incubation in block buffer, then primary antibody incubation and development as described above. For densitometric quantification, dried blots were scanned on an HP Scanjet 4400C scanner and band intensities measured using UN-SCAN-IT software (version 5.1) from Silk Scientific, Inc. (Orem, UT).

RESULTS

Chaetoglobosin K Inhibits Growth of WB-ras1 and H2009 Human Lung Carcinoma Cells

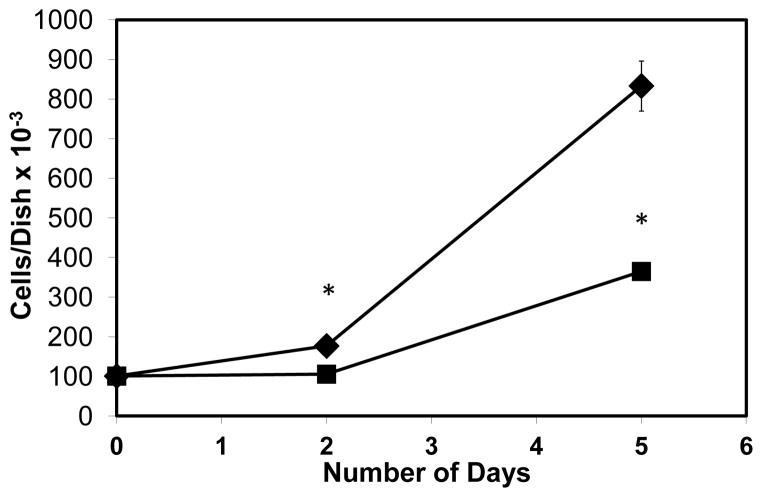

We previously reported that 1 μM ChK inhibited growth of WB-ras1 cells by 70% on day 2 and 91% on day 6 compared to vehicle-treated controls [29]. Cell growth of H2009 cells was also inhibited by ChK as shown in Figure 1. Treatment with 2 μM ChK significantly reduced H2009 human lung carcinoma cells by 40% on day 2 and 56% on day 5 compared to vehicle-treated controls. We previously reported that ChK is non-cytotoxic below 15 μM to WB-ras1 and RG-2 glial cells [29,30].

Fig. 1.

Inhibitory effect of ChK on H2009 human lung carcinoma cell growth. H2009 human lung carcinoma cells were grown to 80–90% confluence for the indicated number of days in the presence (■) or absence (◆ vehicle only) of ChK. Each point represents the mean ± SD (n≥3; p<0.01 compared to controls).

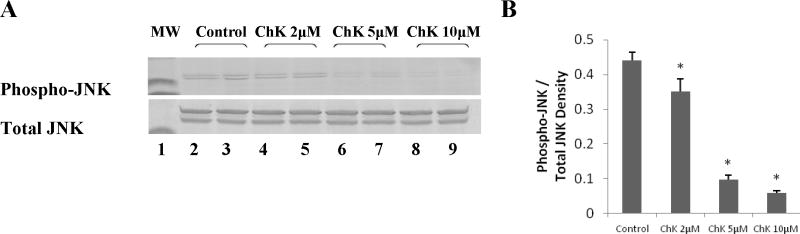

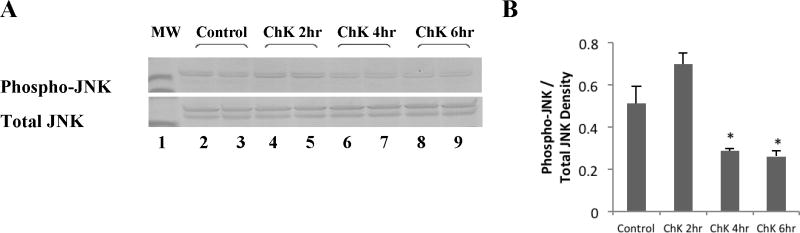

Chaetoglobosin K Modulates JNK Activation in WB-ras1 and Human Lung Carcinoma Cells

Figure 2a shows that treatment of WB-ras1 cells with 2 to 10 μM ChK for 24 hr decreased phosphorylation of JNK on activation sites thr183/tyr185 in a dose-dependent manner (Top panel, lanes 4–9 compared to vehicle control lanes 2 and 3). Total JNK levels did not change (Second panel from top). Figure 2b shows quantification by densitometric scanning of phospho-JNK levels normalized to total JNK levels, indicating an approximately 85% decrease in phosphorylation of JNK at 10 μM ChK. Decreased activation of JNK was detectable as early as 4 hours post-treatment (Figure 3a, top panel, lanes 6–7 compared to control lanes 1–2 and quantification in Figure 3b).

Fig. 2.

Effect of varying concentrations of ChK on JNK phosphorylation in WB-ras1 cells. Cells were grown to 80–90 % confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle or 2, 5, or 10 μM ChK for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of phospho-JNK (a, top panel) or JNK (a, bottom panel) and as described in Methods. Treatment groups were: vehicle (lanes 2–3), 2 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), 5 μM ChK (lanes 6–7), and 10 μM ChK (lanes 8–9). Lane 1 shows pre-stained 41 kD molecular mass markers in each panel. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control)

Fig. 3.

Effect of ChK on JNK phosphorylation in WB-ras1 cells at short treatment times. Cells were grown to 80–90% confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle or 5 μM ChK at varying times as indicated, and extracted for Western blot analysis of JNK and phospho-JNK as described in Methods. Treatment groups were: vehicle (lanes 2–3) or 5 μM ChK for 2 hrs (lanes 4–5), 4 hrs (lanes 6–7), and 6 hrs (lanes 8–9). Lane 1 shows 41 kD pre-stained molecular mass markers in each panel. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control)

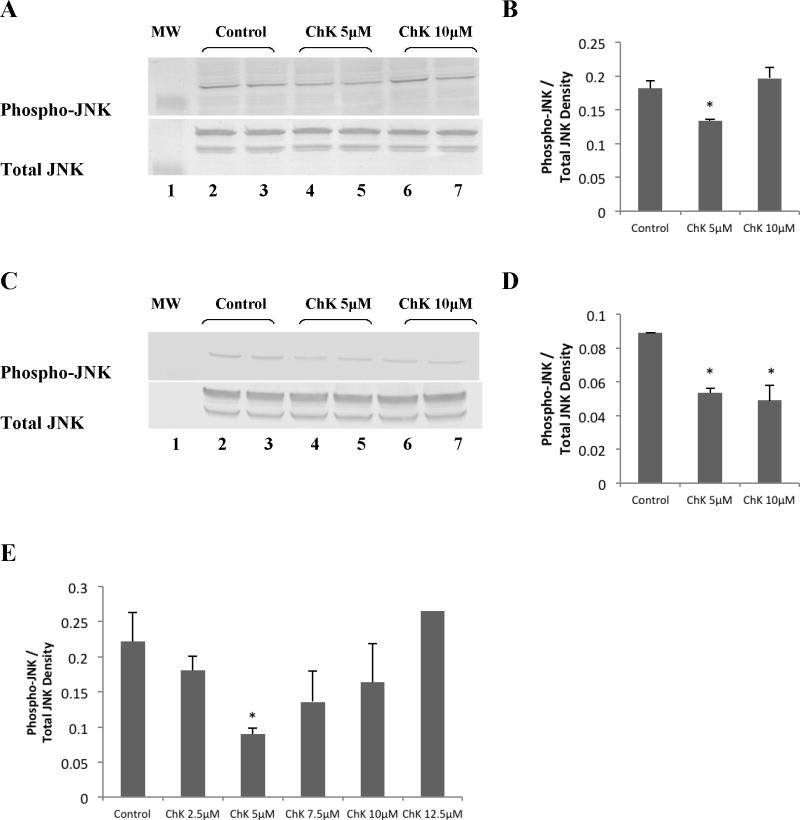

We also tested whether ChK modulates JNK activation in H2009 human lung carcinoma cells. Results show that 5 μM ChK decreased JNK phosphorylation (Figure 4a, top panel, lanes 4–5 compared to vehicle control lanes 2–3). Quantification by densitometry (Figure 4b) indicated an approximately 35% decrease in phosphorylation of JNK at 24 hr treatment compared to controls. At 10 μM ChK, however, phospho-JNK was not significantly different from vehicle-treated controls (Figure 4a, top panel, lanes 6–7 compared to lanes 2–3 and Figure 4b). To see whether a lack of effect at 10 μM ChK occurred in other tumor cells, we treated H1299 lung tumor cells with 5 and 10 μM ChK. The results show that both 5 and 10 μM ChK significantly decreased phospho-JNK levels compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 4c, d). A more detailed time course of ChK’s effect on JNK phosphorylation in H2009 cells showed that significant decreased phosphorylation is observed at 5 μM ChK, but not higher concentrations up to 12.5 μM (Figure 4e). Total JNK levels were not substantially altered by ChK at 5 or 10 μM ChK in either lung tumor cell type (Figure 4a and 4c, lower panels).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ChK on JNK phosphorylation in human lung carcinoma cells. H2009 (a & b) or H1299 (c & d) cells were grown to 80–90% confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle, 5 μM, or 10 μM ChK for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of phospho-JNK or JNK and as described in Methods. Lane 1 shows pre-stained 41 kD molecular mass marker in each panel. Cells were treated with vehicle (lanes 2–3), 5 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), or 10 μM ChK (lanes 6–7) for 24 hrs. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b and d and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control). Western blot densitometry quantification of ChK dose response on phospho-JNK levels in H2009 cells is shown in (e)

Chaetoglobosin K Modulates Akt Activation in WB-ras1 and Human Lung Carcinoma Cells

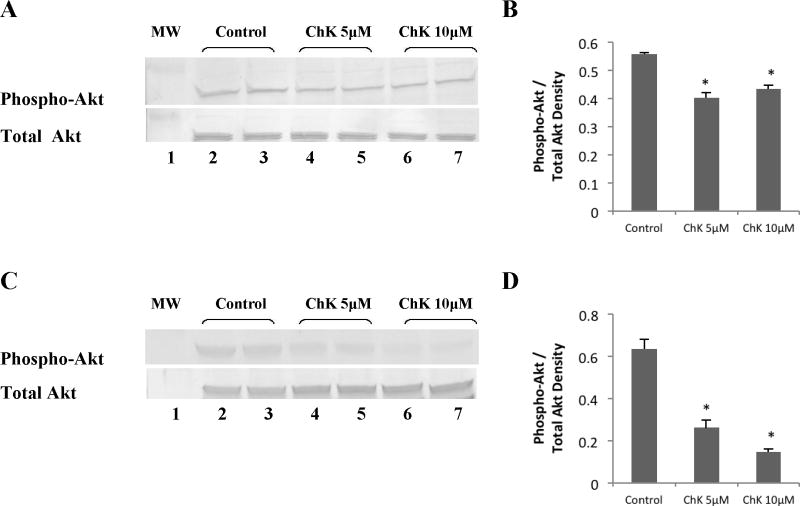

We previously reported decreased Akt phosphorylation at the ser473 activating site by micromolar concentrations of ChK in WB-ras1 cells that occurred over 4–24 hr ([29]; see also Figure 8). Figure 5a shows that 5 and 10 μM ChK also significantly decreased phosphorylation of Akt in H2009 cells on the ser 473 site (top panel, lanes 4–5 compared to lanes 2–3), but did not alter total Akt kinase levels (bottom panel). Quantification by densitometry (Figure 5b) shows an approximately 30% and 25% decrease in phosphorylation of Akt in 5 and 10 μM ChK-treated cells at 24 hr compared to vehicle-treated controls. Figure 5c shows that 5 and 10 μM ChK more robustly decreased phosphorylation of Akt in H1299 cells (top panel, lanes 4–5 compared to lanes 2–3) by approximately 60% and 80%, respectively Figure 5d), and also did not alter total Akt kinase levels (Figure 5c, bottom panel).

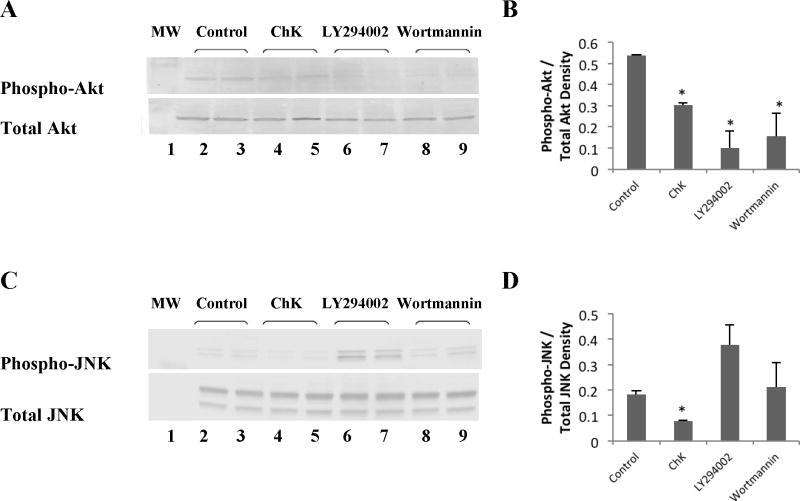

Fig. 8.

Effect of ChK and PI3-kinase inhibitors on Akt and JNK phosphorylation. WB-ras1 cells were grown to 80–90 % confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle, ChK, LY294002, or Wortmannin for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of the phosphorylated or total Akt (a) and JNK (c). Treatment groups were: vehicle (lanes 2–3), 10 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), 20 μM LY294002 (lanes 6–7), and 1 μM Wortmannin (lanes 8–9) for 24 hrs. Lane 1 shows pre-stained molecular mass markers in each panel. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b and d and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control)

Fig. 5.

Effect of ChK on Akt phosphorylation in human lung carcinoma cells. H2009 (a & b) or H1299 (c & d) cells were grown to 80–90% confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle, 5 or 10 μM ChK for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of phospho-Akt or Akt as described in Methods. Treatment groups were: vehicle (lanes 2–3), 5 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), 10 μM ChK (lanes 6–7). Lane 1 shows pre-stained molecular mass markers. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b and d and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control)

Effect of Chaetoglobosin K on Downstream Effectors of JNK and Akt Kinase

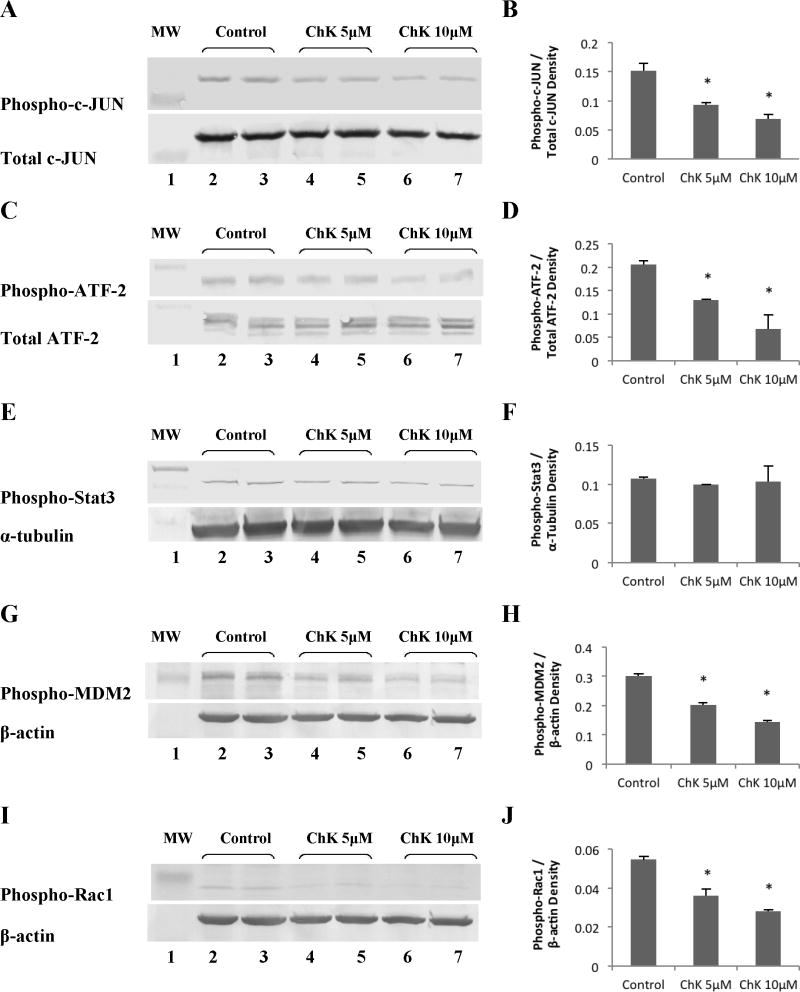

Figure 6 shows that treatment of WB-ras1 cells for 24 hours with 5 or 10 μM ChK decreased phosphorylation on activation sites of two downstream effectors of JNK, c-JUN (a, b) and ATF-2 (c, d), but had no effect on Stat3 phosphorylation on the ser727 activation site (e, f). ChK also decreased phosphorylation of the Akt downstream effectors, MDM2 at the ser166 site (Figure 6g, h) and Rac1 on the inhibitory ser71 inhibitory site (Figure 6i, j).

Fig. 6.

Effect of ChK on downstream effectors of the JNK and Akt pathways. WB-ras1 cells were grown to 80–90 % confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle (lanes 2–3), 5 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), or 10 μM ChK (lanes 6–7) for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins. The phospho-Rac1 blot in i was a re-probe of the phospho-MDM2 blot shown in g, so the identical β-actin control blot was used for normalization as shown. Lane 1 shows pre-stained molecular mass markers. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b, d, f, h, and j and represent the mean ± S.D. (p<0.05 compared to control)

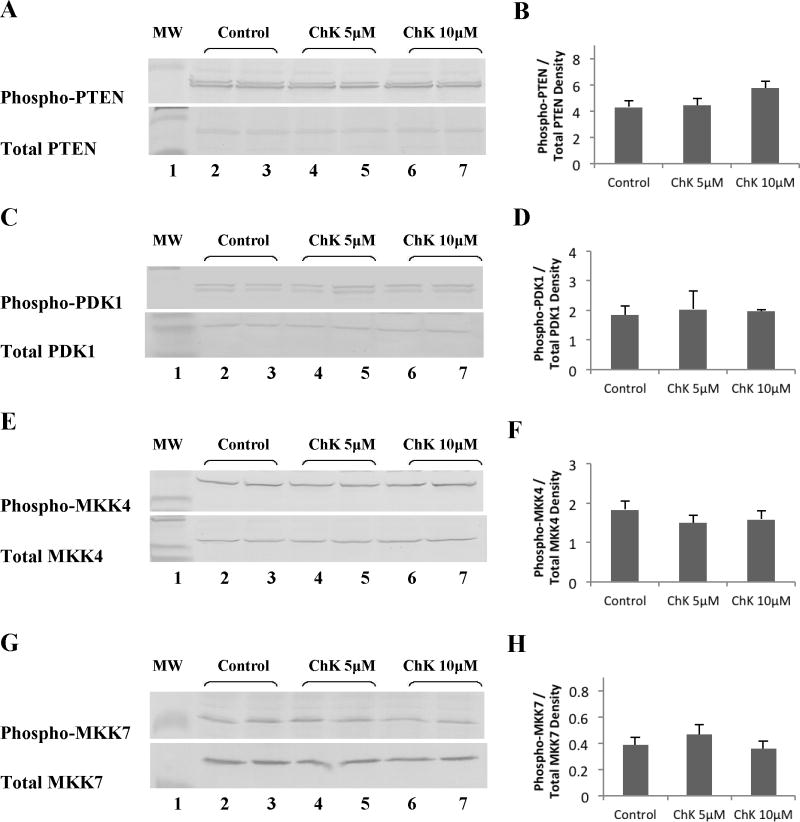

Effect of Chaetoglobosin K on Upstream Activators of JNK and Akt Kinase

Treatment of WB-ras1 cells for 24 hours with 5 or 10 μM ChK had no detectable effect on phosphorylation of two upstream activators of Akt, PTEN at the ser308/thr382,383 destabilizing site (Figure 7a, b) or PDK1 at the autophosphorylation ser241 site (Figure 7c, d). Total PTEN and PDK1 levels were similarly unaltered by ChK. ChK likewise had no effect on the level of phosphorylation on key activation sites of two upstream activators of JNK, MKK4 (Figure 7e, f) and MKK7 (Figure 7g, h). Total MKK4 and MKK7 levels were also unaltered by ChK.

Fig. 7.

Effect of ChK on upstream activators of JNK and Akt kinase. WB-ras1 cells were grown to 80–90 % confluence in 25 cm2 flasks, treated with vehicle (lanes 2–3), 5 μM ChK (lanes 4–5), or 10 μM ChK (lanes 6–7) for 24 hrs, and extracted for Western blot analysis of the indicated proteins. Lane 1 shows pre-stained molecular mass markers. Densitometric quantification of bands is shown in b, d, f, and h and represent the mean ± S.D. No significant difference was found between any of the treatment groups compared to the corresponding vehicle controls (p>0.1).

Comparative Effect of ChK with PI3K Inhibitors

Comparison of ChK with known PI3K inhibitors LY294002 and Wortmannin shows that all three decreased phosphorylation of Akt on ser473 (Figure 8a). ChK-treated WB-ras1 cells (Figure 8a, lanes 4–5) show substantially decreased Akt phosphorylation at 24 hours compared to vehicle-treated control cells (Figure 8a, lanes 2–3). LY294002 and Wortmannin, (Figure 8a, lanes 6–7 and 8–9 respectively) also decreased phosphorylation of Akt on ser473. Densitometric quantification is shown in Figure 8b. Figure 8c and d show that only ChK decreased JNK phosphorylation on the thr183/tyr185 activation sites, however, while LY294002 resulted in increased JNK phosphorylation and Wortmannin had no significant effect on JNK phosphorylation compared to controls.

DISCUSSION

The present report demonstrates the dual inhibitory effect of ChK on both Akt and JNK activation in ras-transformed and human lung carcinoma cells in vitro. These key enzymes in the PI3K and JNK MAPK signaling pathways play an important role in cell cycle transition, proliferation, and metastasis. Dual inhibition of MAPK and PI3K pathways has shown synergy in the treatment of ras-mutated lung cancers not responsive to single PI3K inhibition [32]. The simultaneous inhibition of PI3K and MAPK pathways is often achieved through the administration of multiple drugs that target each signaling pathway separately. Therefore, the development of a single agent that can inhibit both PI3K/Akt and JNK MAPK pathways would be of great therapeutic significance.

ChK treatment led to decreased activation of the Akt downstream effector, MDM2 (Figure 6g, h), as would be expected since Akt activation was decreased. Likewise, ChK treatment led to decreased activation of the JNK downstream effectors, ATF-2 and c-JUN (Figure 6a–d). However, the direct upstream activators of JNK, MKK4 or MKK7, were not affected by ChK (Figure 7e–h). This lack of effect on the direct upstream MAPKK kinases of JNK, suggest that ChK is not acting on a stress receptor in the MEKK1/4KKK→MKK4/7→JNK signaling pathway to inhibit JNK, but through an alternate mechanism that could be effective in tumors with mutations downstream from the activating receptor. The direct upstream activator of Akt, PDK-1, was not altered at the ser241 autophosphorylation site by ChK treatment (Figure 7c, d), but phosphorylation at this site does not definitely determine Akt kinase activity. Likewise, ChK did not alter PTEN phosphorylation on the ser308/thr382, thr383 destabilizing site (Figure 7a, b), but activation of PDK-1 by PTEN is not the only pathway to Akt activation. Thus, further studies are needed to assess ChK’s upstream effects on Akt activation such as direct modulation of Akt by PIP3 [16] and mTOR phosphorylation of Akt on ser473 [33].

We observed that ChK decreases Rac1 phosphorylation on the ser71 inhibitory site (Figure 6i, j) in WB-ras1 cells, which would be predicted to lead to Rac1 activation [34]. Rac1 has been reported to be upstream of JNK in some cells [35,36], activating JNK via MLK3 [36]. Since we do not see an effect of ChK on MKK4 (Figure 7e, f), which is an effector of MLK3 that phosphorylates JNK, we hypothesize that decreased Rac1 phosphorylation by ChK does not crossover to the JNK pathway in our cells. However, the observed decrease Rac1 phosphorylation on ser71 by ChK which would result in Rac1 activation, is consistent with ChK’s inhibitory effect on cytokinesis [29], since inhibition of Rac1 has been shown to be essential for cytokinesis in other systems [37,38].

It is unclear why 10 μM ChK did not alter phosphorylation of JNK, while 5 μM ChK decreased phosphorylation in H2009 cells (Figure 4a, b). This differed from H1299 lung tumor cells and WB-ras1 cells where both 5 and 10 μM ChK decreased phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 4c, d; Figure 2a, b). It is possible that the higher doses of ChK activated the JNK stress pathway in H2009 cells, but not H1299 or WB-ras1 cells, which overcame the inhibitory effect of ChK at 5 μM.

Like ChK, the PI3K inhibitors, Wortmannin and LY294002, inhibited Akt phosphorylation on the ser473 activation site (Figure 8a, b). However, unlike ChK which inhibited JNK phosphorylation at the Thr183/Tyr185 activation site, Wortmannin had no effect or increased JNK phosphorylation at this site (Figure 8c, d). These results are consistent with previous reports showing increased JNK activation in cells treated with Wortmannin and LY294002 [34]. Thus, ChK does not act as a classic PI3K inhibitor, but rather, has unique effects that are more favorable for inhibiting growth of tumor cells with over activated JNK.

We detected no effect of ChK on Stat3 phosphorylation on ser727 in WB-ras1 cells (Figure 6e, f) or in H2009 cells (unpublished observations). Lim and Cao previously showed that activated JNK phosphorylated Stat3 on ser727 in vitro and that Stat3 was also phosphorylated at this site in vivo by cotransfection of JNK1 with MEKK1 [39]. It is possible that Stat3 does not serve as a target of JNK in non-cotransfected cells, or serves as a target of JNK only in selected cell types that do not include the ones used in this study. Stat3 can also be phosphorylated on tyr705 by JAK, which leads to activation via dimer formation, followed by nuclear translocation [40]. We predict that ChK would not activate Stat3 by tyrosine phosphorylation, as activated Stat3 has anti-apoptotic and oncogenic potential.

Several current targeted tumor therapies such as erlotinib, gefitinib, and cetuximab, target the membrane EGF receptor [5–8,11,41]. However, patients with mutations downstream from EGFR, often do not respond well to these therapies. Therefore, inhibitors that target downstream kinases or regulatory molecules in the EGF and other growth signaling pathways are needed for such patients. An example of such a therapy is vemurafenib, which targets Raf and has recently been marketed to treat advanced melanomas [12]. ChK’s ability to inhibit Akt and JNK downstream kinases in our model ras-transformed cells as well as human lung tumor cells, suggests that ChK would be effective for some patients with mutations downstream of membrane receptors. The unique dual inhibitory effect of ChK on these two important growth signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis earmarks ChK for further studies to determine its molecular target(s).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health, grant 1R15CA135415.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Schechter AL, Stern DF, Vaidyanathan L, Decker SJ, Drebin JA, Greene MI, et al. The neu oncogene: an erb-B-related gene encoding a 185,000-Mr tumour antigen. Nature. 1984;312:513–516. doi: 10.1038/312513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jou YS, Layhe B, Matesic DF, Chang CC, de Feijter AW, Lockwood L, et al. Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication and malignant transformation of rat liver epithelial cells by neu oncogene. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:311–317. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adjei AA. Blocking oncogenic Ras signaling for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1062–1074. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain M, Arvanitis C, Chu K, Dewey W, Leonhardt E, Trinh M, et al. Sustained loss of a neoplastic phenotype by brief inactivation of MYC. Science. 2002;297:102–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1071489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druker BJ. STI571 (Gleevec™) as a paradigm for cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S14–S18. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezjak A, Tu D, Seymour L, Clark G, Trajkovic A, Zukin M, et al. Symptom improvement in lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib: quality of life analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3831–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Jr, Prager D, Belani CP, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross JS, Schenkein DP, Pietrusko R, Rolfe M, Linette GP, Stec J, et al. Targeted Therapies for Cancer 2004. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:598–609. doi: 10.1309/5CWP-U41A-FR1V-YM3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong HQ. Molecular targeting therapy for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:S69–S77. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaherty KT, Yasothan U, Kirkpatrick P. Vemurafenib. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:811–812. doi: 10.1038/nrd3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne PH, Khwaja A, Marte BM, Pappin D, Das P, et al. Role of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase in cell transformation and control of the actin cytoskeleton by Ras. Cell. 1997;89:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivanco I, Sawyers CI. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokoe D, Stephens LR, Copeland T, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Painter GF, et al. Dual Role of the Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the Activation of Protein Kinase B. Science. 1997;277:567–570. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Dan HC, Sun M, Liu Q, Sun XM, Feldman RI, et al. Akt/protein kinase B signaling inhibitor-2, a selective small molecule inhibitor of Akt signaling with antitumor activity in cancer cells overexpressing Akt. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4394–4399. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Restuccia DF, Hemmings BA. Blocking Akt-ivity. Science. 2009;325:1083–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1179972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun M, Wang G, Paciga JE, Feldman RI, Yuan ZQ, Ma XL, et al. AKT1/PKBalpha kinase is frequently elevated in human cancers and its constitutive activation is required for oncogenic transformation in NIH3T3 cells. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segrelles C, Ruiz S, Perez P, Murga C, Santos M, Budunova IV, et al. Functional roles of Akt signaling in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Affara NI, Schanbacher BL, Mihm MJ, Cook AC, Pei P, Mallery SR, et al. Activated Akt-1 in Specific Cell Populations During Multi-stage Skin Carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2773–2782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malik SN, Brattain M, Ghosh PM, Troyer DA, Prihoda T, Bedolla R, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of phospho-Akt in high Gleason grade prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1168–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreisberg JI, Malik SN, Prihoda TJ, Bedolla RG, Troyer DA, Kreisberg S, et al. Phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) is an excellent predictor of poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5232–5236. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonyak MA, Kenyon LC, Godwin AK, James DC, Emlet DR, Okamoto I, et al. Elevated JNK activation contributes to the pathogenesis of human brain tumors. Oncogene. 2002;21:5038–5046. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelberg D. Stress-activated protein kinases - tumor suppressors or tumor initiators? Semin Cancer Biol. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khatlani TS, Wislez M, Sun M, Srinivas H, Iwanaga K, Ma L, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is activated in non-small-cell lung cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:2658–2666. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutler HG, Crumley F, Cox R. Chaetoglobosin K: a new plant growth inhibitor and toxin from Diplodia macrospora. J Agric Food Chem. 1980;28:139–142. doi: 10.1021/jf60227a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tikoo A, Cutler H, Lo SH, Chen LB, Maruta H. Treatment of Ras-induced cancers by the F-actin cappers Tensin and Chaetoglobosin K, in combination with the Caspase-1 inhibitor N1445. Cancer J Sci Am. 1999;5:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matesic DF, Villio KN, Folse SL, Garcia EL, Cutler SJ, Cutler HG. Inhibition of cytokinesis and Akt phosphorylation by chaetoglobosin K in ras-transformed epithelial cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmocol. 2006;57:741–754. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matesic DF, Blommel ML, Sunman JA, Cutler SJ, Cutler HG. Prevention of organochlorine-induced inhibition of gap junctional communication by chaetoglobosin K in astrocytes. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2001;17:395–408. doi: 10.1023/a:1013752717500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidorova TS, Matesic DF. Protective effect of the natural product, Chaetoglobosin K, on lindane- and dieldrin-induced changes in astroglia: identification of activated signaling pathways. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1297–308. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon T, Kwon DY, Chun J, Kim JH, Kang SS. Akt protein kinase inhibits Rac1-GTP binding through phosphorylation at serine 71 of Rac1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:423–428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murga C, Zohar M, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS. Rac1 and RhoG promote cell survival by the activation of PI3K and Akt, independently of their ability to stimulate JNK and NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2002;21:207–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang QG, Wang XT, Han D, Yin XH, Zhang GY, Xu TL. Akt inhibits MLK3/JNK3 signaling by inactivating Rac1: a protective mechanism against ischemic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1886–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Logan MR, Mandato CA. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton by PIP2 in cytokinesis. Biol Cell. 2006;98:377–388. doi: 10.1042/BC20050081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canman JC, Lewellyn L, Laband K, Smerdon SJ, Desai A, Bowerman B, Oegema K. Inhibition of Rac by the GAP activity of centralspindlin is essential for cytokinesis. Science. 2008;322:1543–1546. doi: 10.1126/science.1163086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim CP, Cao X. Serine phosphorylation and negative regulation of Stat3 by JNK. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31055–31061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rawlings JS, Rosler KM, Harrison DA. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1281–1283. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong MK, Lo AI, Lam B, Lam WK, Ip MS, Ho JC. Erlotinib as salvage treatment after failure to first-line gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1107-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]