Abstract

Extensive research on the Ras proteins and their functions in cell physiology over the past 30 years has led to numerous insights that have revealed the involvement of Ras not only in tumorigenesis but also in many developmental disorders. Despite great strides in our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of action of the Ras proteins, the expanding roster of their downstream effectors and the complexity of the signalling cascades that they regulate indicate that much remains to be learnt.

Discoveries made in the late 1970s and the early 1980s revealed that the transforming activities of the rat-derived Harvey and Kirsten murine sarcoma retroviruses contribute to cancer pathogenesis through a common set of genes, termed ras (for rat sarcoma virus). Soon thereafter, the use of recently developed techniques in gene transfer, DNA sequencing and DNA mapping led to the identification of ras genes as key players in experimental transformation as well as in human tumour pathogenesis. Unanswered by these initial discoveries, however, was the signalling context in which the Ras proteins operate — which proteins impart signals to Ras and how do the resulting functionally activated Ras proteins pass signals on to downstream targets within the cell? The answers to these questions were complicated by the discoveries of multiple Ras regulators and a large cohort of downstream effectors, each with a distinct pattern of tissue-specific expression and a distinct set of intracellular functions. Despite the lack of a complete understanding of the normal and pathological functions of Ras, significant progress has been made over the past three decades. Here, we chronicle some of these milestones, with particular emphasis on the role of Ras in normal and deregulated cellular physiology.

Cancer precursors

The cellular homologues of the viral Harvey and Kirsten transforming ras sequences were first identified in the rat genome in 1981 (REF. 1) and were subsequently found in the mouse2 and human3 genomes. These discoveries revealed that the ras oncogenes behaved, at least superficially, like the src oncogene of Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), the origins of which were first reported in 1976 (REF. 4). Thus, protooncogenes residing in the genomes of normal cells can be activated into potent oncogenes by retroviruses, which acquire these sequences and convert them into active oncogenes. The Harvey sarcoma virus-associated oncogene was named Ha-ras (H-ras in mammals), whereas that of Kirsten sarcoma virus was termed Ki-ras (K-ras in mammals). Mutant alleles of these ras sequences were soon discovered in many human cancer cell lines, including those of the bladder, colon and lungs5–7 (TIMELINE).

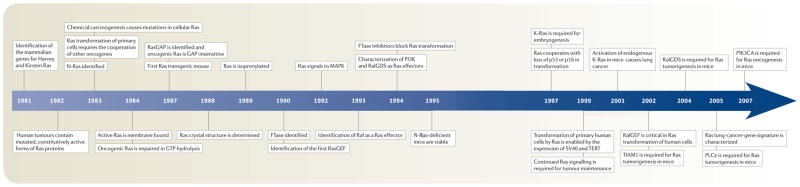

Timeline. Key events in the field of Ras research.

GAP, GTPase-activating proteins; GEF, guanine nucleotide-exchange factors; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PIK3A, phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit-α; PLC, phospholipase C; RalGDS, Ral guanine nucleotide-dissociation stimulator; SV40, simian virus-40;TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; TIAM1, T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-1.

Detailed sequence analyses revealed that the oncogenic alleles invariably differed from their wild-type counterparts by point mutations that affect the reading frames of the various ras oncogenes. The resulting amino-acid replacements were usually found to affect residue 12, and also less commonly residues 13 and 61 (REFS 8–11). By 1983, the third member of the mammalian family of ras-related genes, N-ras, had been cloned from neuroblastoma and leukaemia cell lines12–15 (FIG. 1). This gene was also found to contain activating point mutations in certain human tumours.

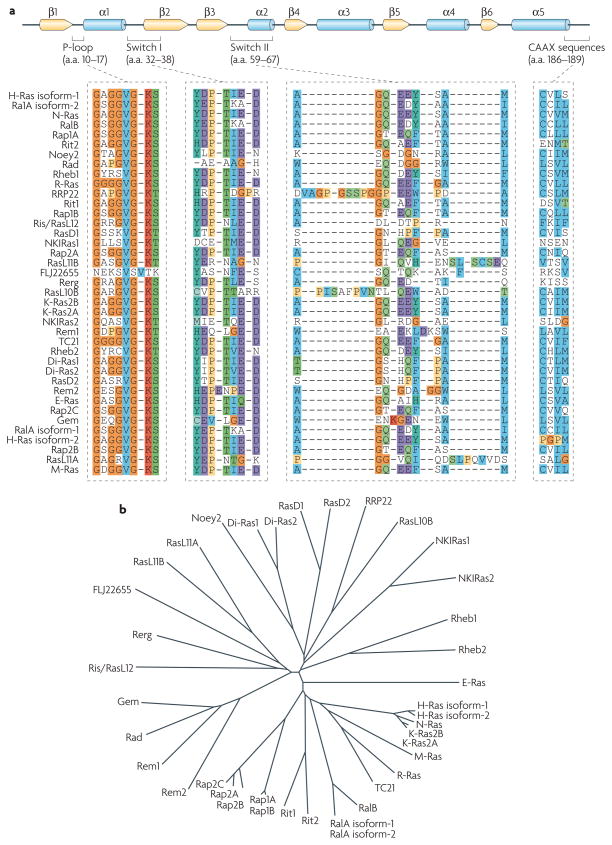

Figure 1. The ras family of small gTPases.

a | The primary structure of Ras proteins. The Ras family of GTPases encompasses 36 genes, which encode 39 Ras proteins (20–29 kDa) in the human genome. Most of the Ras family proteins have been characterized and found to regulate important cellular processes, such as growth, cytoskeletal rearrangements, adhesion, motility and differentiation. Secondary structural elements are shown as arrows (for β-sheets, yellow) and cylinders (for α-helices, blue). Ras family members share substantial primary sequence homology in their N termini, particularly in the phosphate-binding loop (P-loop) and the nucleotide-sensitive switch I and II regions. The C terminus contains the membrane-targeting CAAX sequences223. H-Ras isoform-1 numbering indicated. b | Overall sequence comparison among Ras proteins. The Ras family radial tree was generated using matrices derived from a ClustalW multiple sequence alignment of the various Ras family members. a.a., amino acids.

The efficiency of the ras lesion in initiating cellular transformation in primary cells was soon questioned when it was discovered that a ras oncogene could not transform freshly isolated rodent embryo cells. Consequently, three reports that were published in 1983 described the ability of H-Ras-Val12 to transform primary cells that had previously been immortalized by either carcinogens16 or transfection with myc, SV40 large T antigen or adenovirus E1A oncogene17,18. These findings extended the concept of multistep carcinogenesis and suggested that mutant Ras proteins can only transform (to a tumorigenic state) cells that have undergone predisposing changes. As verified in various cell types19–21, these predisposing changes usually involved the acquisition by cells of an ability to proliferate indefinitely in culture — the phenotype of cell immortalization (BOX I).

Box 1. The Ras tumour-suppressor effect.

Oncogenic Ras has been shown to cause senescence in primary cells through the activation of the p53–p21WAF and/or p16INK4A–Retinoblastoma (Rb) tumour-suppressor pathways212–214. These observations suggested that the normal response of ‘uninitiated’ naive cells to hyperactive Ras signalling is to undergo cell-cycle arrest and/or senescence rather than unlimited proliferation and/or transformation. Indeed, the susceptibility of certain normal cells to Ras-mediated transformation would seem to rely mostly on prior inactivation of these tumour-suppressor pathways (for example, see REF. 215). In addition, the findings that Ras-induced senescence in primary cells explained the molecular basis of the oncogenic cooperation model that was proposed in 1983 (see REFS 17,18), as Ras-collaborating oncoproteins, such as E1A, SV40 and E6/E7 are all well-known inactivators of the Rb and the p53 pathways. Collectively, these observations suggested that Ras activation in normal cells causes a halt in cell proliferation rather than an initiation of tumorigenesis.

Other groups have reported that human embryonic fibroblasts are resistant to Ras-induced cellular senescence216. Furthermore, in vivo expression of oncogenic K-Ras at levels comparable to those of its endogenous counterparts caused cellular transformation217,218. These and similar experiments led to the finding that p16 was the key factor in determining whether cells become senescent or are transformed in response to Ras activation. High levels of Ras expression cause an acute elevation of p16, resulting in cell-cycle arrest. By contrast, moderate activation of Ras (such as that mimicked in the endogenous K-Ras mouse models) does not cause an acute p16 response, allowing Ras-induced transformation. Similarly, Ras activation in the background of suppressed p16 (for example, in cells maintained at low-stress-culture conditions or by using short hairpin RNA against p16) causes cellular proliferation.

Ras activation of p16 and p53 seem to depend, in part, on the activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway219 through unidentified mechanisms. Ras activation has been shown to cause elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels220, and ROS promote p38 activation221. However, whether ROS are the mediators of Ras activation of the p38 MAPK remains to be fully delineated. The Ras-induced Raf–MAPK pathway might feed into the p53 pathway by activating the p38-regulated/activated protein kinase (PRAK), which in turn phosphorylates and activates p53 directly222. MDM2, murine double minute-2; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; p14/19ARF, p14ARF in humans and p19ARF in mice.

By 1984, mutant K-RAS alleles were found in lung carcinoma specimens, indicating that these mutations did not arise as a consequence of culturing cancer cells in vitro22,23. Moreover, specific associations were found between the various RAS oncogenes and particular types of human cancer (TABLE 1). K-RAS mutations were frequent in pancreatic24 and colonic carcinomas25, H-RAS mutations were predominantly found in bladder carcinomas26, and N-RAS mutations were linked primarily to lymphoid malignancies27–31 and melanomas32.

Table 1.

Ras mutations in human cancers

| Tissue | H-Ras | K-Ras | N-Ras |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenal gland | 1% | 0% | 5% |

| Biliary tract | 0% | 32% | 1% |

| Bone | 2% | 1% | 0% |

| Breast | 1% | 5% | 1% |

| Central nervous system | 0% | 1% | 2% |

| Cervix | 9% | 8% | 1% |

| Endometrium | 1% | 14% | 0% |

| Eye | 0% | 4% | 1% |

| Gastrointestinal tract (site indeterminate) | 0% | 19% | 0% |

| Haematopoietic and lymphoid tissue | 0% | 5% | 12% |

| Kidney | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| Large intestine | 0% | 32% | 3% |

| Liver | 0% | 7% | 4% |

| Lung | 1% | 17% | 1% |

| Meninges | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Oesophagus | 1% | 4% | 0% |

| Ovary | 0% | 15% | 4% |

| Pancreas | 0% | 60% | 2% |

| Parathyroid | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Peritoneum | 0% | 6% | ND |

| Pituitary | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Placenta | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Pleura | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Prostate | 6% | 8% | 1% |

| Salivary gland | 16% | 4% | 0% |

| Skin | 5% | 2% | 19% |

| Small intestine | 0% | 20% | 25% |

| Stomach | 4% | 6% | 2% |

| Testis | 0% | 5% | 4% |

| Thymus | 0% | 15% | 0% |

| Thyroid | 4% | 3% | 7% |

| Upper aerodigestive tract | 9% | 4% | 3% |

| Urinary tract | 12% | 4% | 3% |

Data derived from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK. ND, not determined.

Experimentally induced tumours were also found to harbour mutant ras genes. For example, mouse mammary and skin tumours that were induced by the topical application of carcinogens contained H-Ras mutations33–35, whereas carcinogen-induced thymomas carried activating N-Ras mutations36. Other long-known carcinogens, such as ionizing radiation, were also found to cause K-Ras mutations in mice37 as well as in tissue-culture cells38. However, these discoveries provided no insight into the main puzzle surrounding the mutant, oncogenic ras alleles: why were the activating mutations invariably localized to a small number of sites in the reading frames of these genes?

Activated mutants and the GTPase cycle

Ras proteins were initially described to bind to guanine nucleotides in 1980 by edward Scolnick’s group, which was investigating the biochemical features of the viral H-Ras protein39. This binding suggested that Ras might function analogously to the heterotrimeric G proteins, which had previously been found to possess an intrinsic GTP hydrolysis (or GTPase) activity that shuttles them from an active to an inactive signalling state. The reactivation of these G proteins occurred when their bound GDP nucleotide was ejected, making room for the binding of the more abundant cellular GTP (reviewed in REF. 40).

The actual biochemical proof that Ras proteins were indeed GTPases came several years later. In 1984, three groups reported that mutated Ras oncoproteins differ functionally from their normal counterparts41–43. The oncogenic forms of Ras exhibited impaired GTPase activity, which suggested that the hydrolysis of GTP somehow terminates the activated state of the protein, which is consistent with the presumed analogy to the behaviour of G proteins. Furthermore, the link between the much-studied Gly-to-Val substitution of residue 12 of H-Ras and GTP hydrolysis was made the following year by Frank McCormick’s group, which noted that antibodies that are specific to that region blocked GTP binding44. Other oncogenic mutations (such as Gln61leu in H-Ras) were also shown to impair GTP hydrolysis45 and other oncogenic forms of Ras were later determined to be impaired in GTP hydrolysis (for example, REF. 46). However, the extent of such impairment did not always correlate with transformation, suggesting that compromised intrinsic GTP hydrolysis was necessary but not sufficient for aberrant Ras activation.

Post-translational modifications

Post-translational lipid processing of Ras was found to be another key determinant of its functioning. An initial study in this area, published in 1982, showed that the mature form of viral H-Ras localized to the cell membrane47. Several months later it was demonstrated that viral H-Ras is palmitoylated at the C terminus; the resulting attached lipid moiety facilitated its association with the membrane48. The functional connection between this lipid modification and Ras function was made by Douglas Lowy’s group in 1984, which showed that lipid binding and membrane association were actually required for the transforming activity of the viral H-Ras oncoprotein49,50. working with cellular H-Ras, Stuart Aaronson’s group proceeded to demonstrate that this C-terminal processing and membrane recruitment of Ras is a prerequisite to its biochemical activation51.

The molecular mechanisms of Ras lipid processing were laid out over the subsequent 5 years through a series of observations using yeast genetics, protein biochemistry and in vitro cellular systems52–57 (FIGS 2,3). Indeed, the C-terminal CAAX motif, previously found to be important for Ras function, was found to be the target of a post-translational modification that involved the addition of a farnesyl isoprenoid lipid, catalysed by the enzyme farnesyl transferase (FTase). Subsequent studies determined that this prenylation reaction is followed by the proteolytic cleavage of the AAX sequence, catalysed by Ras-converting enzyme-1 (RCE1) and the carboxymethylation of the now terminal Cys residue by the isoprenylcysteine carboxymethyltransferase-1 (ICMT1) enzyme.

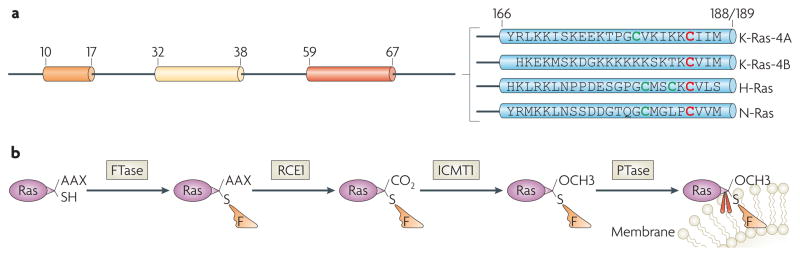

Figure 2. C-terminal processing of ras proteins.

a | C-terminal sequences. The C terminus is highly divergent among the Ras family members and contains the membrane-targeting sequences223. The C-terminal sequences of Kirsten- (K-), Harvey- (H-) and neuroblastoma- (N-) Ras proteins are shown. Cys residues in red or green are farnesylated or palmitoylated, respectively. b | C-terminal processing. A farnesyl pyrophosphate moiety (orange) is covalently attached to the newly-synthesized cytoplasmic Ras proteins by the enzyme farnesyltransferase (FTase)54–56. This reaction is followed, in the endoplasmic reticulum, by the proteolytic cleavage of the last three amino-acid residues (AAX) by Ras-converting enzyme-1 (RCE1), and by the carboxymethylation of the last Cys residue by ICMT1 (for example, see REF. 224). The C-terminal Lys residues in K-Ras-4B are sufficient to anchor it in the membrane, whereas H-, N- and K-Ras-4A require a palmitoylation step (by a palmitoyltransferase (PTase)) in which a palmitoyl moiety (red) is attached to the C-terminal upstream Cys residues before their insertion in the membrane is stabilized57. In the presence of FTase inhibitors, both K-Ras-4A and N-Ras can become prenylated by geranylgeranyl transferase225.

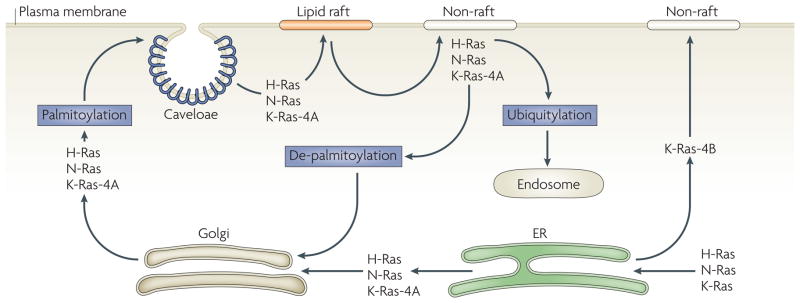

Figure 3. Recycling of ras proteins.

Cytoplasmic Ras proteins traffic through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where they are post-translationally processed by farnesyltransferase. Farnesylated Kirsten (K)-Ras-4B is then transported directly to the plasma membrane through unknown mechanisms226,227, whereas Harvey- (H-), neuroblastoma- (N-), and K-Ras-4A transit through the Golgi apparatus and undergo a palmitoylation step before homing to plasma-membrane invaginations enriched with the cholesterol-binding protein caveolin (see REF. 228). Efficient activation of these Ras proteins might require their localization to specific plasma-membrane microdomains (lipid raft or non-raft domains) that regulate the nature of the recruited Ras effectors (and hence the identities of the signalling pathways that are activated downstream of Ras) and the amplitude of the Ras signal activation168. Endocytosed and de-palmitoylated H- and N-Ras are shuttled back from the plasma membrane to the Golgi229 where they are recycled. Alternatively, ubiquitylated plasma-membrane-tethered H- or N-Ras (representing ~2% of total cellular H- or N-Ras levels) are de-ubiquitylated and targeted to endocytic vesicles230. The nature and function of the signalling circuitry that Ras proteins execute in endosomes and other cytoplasmic organelles is an emerging area of intense investigation.

Although these CAAX-signal modifications appeared to be essential for the association of Ras with the plasma membrane, other studies identified the requirement for a second C-terminal signal that facilitates full membrane recruitment and hence full Ras function (for example, see REF. 57). For K-Ras-4B, this second signal is a string of positively-charged lys residues upstream of the C terminus that are sufficient to anchor the protein to the membrane. However, prenylated H-Ras, N-Ras and K-Ras-4A require a further palmitoylation step in which a palmitoyl moiety is attached to upstream C-terminal Cys residues before their anchoring in the membrane is stabilized. The enzymes that catalyse these various steps became attractive targets for drug development efforts.

Upstream regulation

The first indications that Ras activity is modulated by associated proteins came from the group of James Feramisco in 1984, who observed increased GTPase activity of cellular H-Ras in response to treatment with epidermal growth factor (EGF)58. Indeed, Ras activation appeared to be vital for signalling by extracellular mitogens, as microinjected antibodies that were directed against Ras blocked the serum-stimulated cellular growth of NIH 3T3 cells59 and the growth factor-induced differentiation of PC12 cells60. At the time, multiple groups also described the activation or inhibition of Ras proteins by growth factors61 and cytokines62–64. Similar observations made in non-mammalian systems, such as Xenopus laevis oocytes65, suggested that Ras proteins, similar to G proteins, can function as transducers of signals arising from plasma-membrane-associated receptors66.

Still, the nature of the factors that regulate the activation and inactivation of Ras proteins remained unclear. In fact, inactivators of Ras signalling were first identified with the discovery of Ras GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). The first member of the RasGAP family was identified and purified by the groups of both McCormick and Scolnick and was found to possess GTPase-promoting functions that preferentially functioned on the normal, but not oncogenic, N-Ras or H-Ras proteins46,67–69. The group of Stuart Aaronson reported 1 year later that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor stimulation promoted Tyr phosphorylation of RasGAP, thereby enabling its membrane translocation70 and providing the first molecular link between mitogenic signalling and Ras regulators. Soon thereafter, the second RasGAP, neurofibromin-1 (NF1), was identified and found to be disrupted in patients with neurofibromatosis71–74. This finding provided the earliest indication of aberrant Ras signalling in a developmental disease (discussed below).

Although informative, these studies did not reveal the proteins that are responsible for the functional activation of Ras. Such proteins were named either guanine nucleotide-exchange factors (GEFS) or guanine nucleotide-releasing proteins (GRFs). The yeast cell-division- cycle-25 (Cdc25) protein (not to be confused with the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphatase of the same name) was the first RasGEF to be identified75,76 and was found to activate Ras by stimulating its guanine nucleotide-exchange activity.

The mammalian counterparts of Cdc25 were characterized in cellular extracts several years later by a number of groups77–81, in efforts that culminated with the cloning of the first mammalian RasGEF, termed son of sevenless (SOS) because of its contribution to the morphogenesis of the Drosophila melanogaster eye82. Indeed, SoS served as the prototype for a number of other proteins that exhibited accelerated guanine nucleotide-exchange activity towards Ras, collectively forming the Cdc25 family of RasGEFs.

The connection between RasGEFs and upstream mitogenic signalling was described by a number of groups in 1993, when it was demonstrated that the adaptor protein growth factor receptor-bound protein-2 (GRB2) associates with the eGF receptor and concomitantly attaches to the mammalian SoS83–87. Subsequently, several more Ras-specific GAPs and GEFs were characterized, each possessing, in addition to the GAP or Cdc25 domains, a number of signalling motifs, such as the Src-homology-2 (SH2) or SH3 modules, which enable their physical and functional interactions with a variety of regulatory partners88,89. The molecular mechanisms of how these GAPs and GEFs regulate the activity of Ras GTPases became apparent only later.

Anatomy of Ras regulation

The sequence homologies between Ras proteins and the functionally analogous heterotrimeric G proteins (which were better characterized at the time) expedited much of the initial biochemical and structural investigations of Ras GTPases in the 1980s (for example, see REFS 90,91). Comparative analyses accompanied by site-directed mutagenesis studies identified residues in the Ras N and C termini as being important for GTP binding and cell transformation92–96. Moreover, these studies produced a wealth of mutant Ras proteins that have proven to be of great use in deciphering downstream signal-transduction pathways.

Ras three-dimensional structure

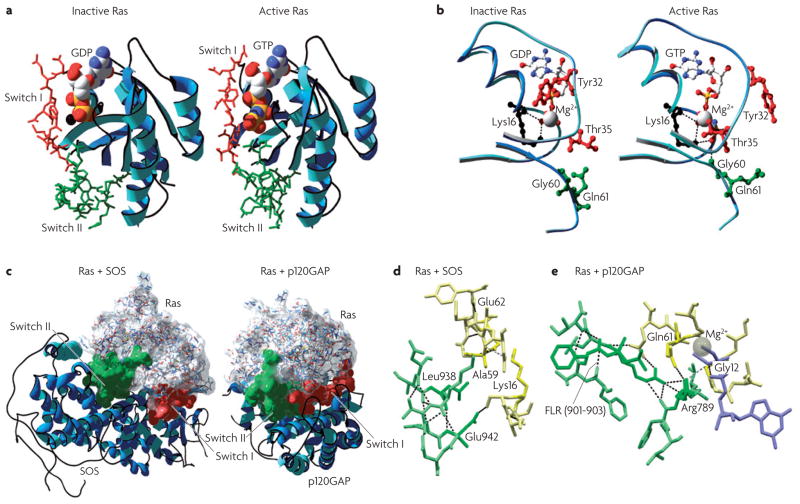

Detailed insights into the three-dimensional fold of Ras proteins were provided in 1990 by crystallographic determinations of the structures of GDP- and GTP-bound Ras proteins97–100 and of their mutant variants101,102. The overall Ras structure was shown to consist of a hydrophobic core of six stranded β-sheets and five α-helices that are interconnected by a series of ten loops (FIG. 4a). Five of these loops are situated on one facet of the protein and have crucial roles in determining the high affinity nucleotide interactions of Ras and in regulating GTP hydrolysis. In particular, the GTP γ-phosphate is stabilized by interactions that are established with the residues of loops 1, 2 and 4 (for example, lys16, Tyr32, Thr35, Gly60 and Gln61; see FIG. 4b). A prominent role is attributed to Gln61, which stabilizes the transition state of GTP hydrolysis to GDP, in addition to participating in the orientation of the nucleophilic attack that is necessary for this reaction. As such, oncogenic mutations of Gln61 reduce the intrinsic GTP hydrolysis rate, thereby placing the Ras protein in a constitutively active state.

Figure 4. Anatomy of ras regulation.

a | The structure of Ras. The Ras three-dimensional fold is shown to consist of six β-sheets and five α-helices interconnected by a series of ten loops. Crystallographic structures of inactive RasGDP99 (2.0 Å resolution; Protein Data Bank code 4q21) and active RasGppNHp97 (1.35 Å resolution; PDB code 5p21) are shown, with the nucleotide-sensitive switch I and II regions depicted in red and green, respectively. The GDP and GTP nucleotides are shown as balls. b | Nucleotide-dependent structural rearrangements. The differences between the inactive GDP-bound and the active GTP-bound Ras reside mainly in two regions, termed switch I (~residues 30–40) and switch II (~residues 60–76), both of which are required for the interactions of Ras with its regulators and effectors. The γ-phosphate induces significant changes in the orientation of the switch II region through the interactions that it establishes with Thr35 and Gly60. Notably, these two residues are among the most conserved residues in the GTPase family, suggesting that the mechanisms of GTP binding (and hydrolysis) are essentially the same among various members. c | Ras in complex with its regulators. The crystal structures of Ras in complex with the DBL homology (DH)/pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of son of sevenless104 (SOS) (left; 2.8 Å resolution; PDB code 1bkd) and with p120 Ras GTPase-activating protein103 (p120GAP) are shown (right; 2.5 Å resolution; PDB code 1wq1). d | The Ras guanine nucleotide-exchange factor (RasGEF) binding interface. The insertion of the α-helical hairpin of SOS (green; specifically Leu938 and Glu942) into the nucleotide pocket of Ras (yellow) reorientates Ala59 and perturbs the phosphate-binding (P)-loop, facilitating guanine nucleotide ejection. e | The RasGAP binding interface. Similarly, the insertion of the catalytic Arg789 finger of GAP into the active site of Ras stabilizes Gln61 and contributes to GTP hydrolysis. All structures were visualized with DeepView-Swiss-PdbViewer, and images were generated with POV-Ray.

The structural differences between the RasGDP and the RasGTP conformations reside mainly in two highly dynamic regions, termed switch i (residues 30–40) and switch ii (residues 60–76). Both regions are required for the interactions of Ras with upstream as well as downstream partners (see also FIG. 2a). The binding of GTP alters the conformation of switch i, primarily through the inward reorientation of the side chain of Thr35, thereby enabling its interactions with the GTP γ-phosphate as well as the Mg2+ ion. Similarly, the γ-phosphate induces significant changes in the orientation of the switch ii region through interactions it establishes with Gly60 (FIG. 4b).

GAP- and GEF-mediated regulation of Ras activity

The structural details of GAP-mediated and GEF-mediated regulation of Ras activity were ultimately laid out by the groups of both Alfred Wittinghofer and John Kuriyan in the late 1990s, when the structures of H-Ras in complex with the p120GAP GRD103 (GAP-related domain) and that of H-Ras in complex with the catalytic domain of SoS104 were reported (FIG. 4c,d,e). Importantly, the binding of the variable loop of GAP α7 to the switch I of Ras establishes the pairing specificity between GAP and Ras. This is followed by a high affinity interaction with the GAP Phe-Leu-Arg (FlR) motif, which stabilizes the two switch domains as a highly conserved GAP Arg-finger loop88 inserts itself into an active site, provoking a ~1,000-fold acceleration in GTP hydrolysis.

An analogous mechanism has been described for the SOS-mediated ejection of guanine nucleotides from Ras. During the course of this interaction, an α-helical hairpin of the Cdc25 domain pries open the switch I and switch II domains of Ras, causing a series of side-chain rearrangements that involve Ala59, which reorientates and inserts itself into the Mg2+-binding cleft. These changes, together with structural perturbations of the phosphate-binding loop, cause a 10,000-fold enhancement in the GDP ejection rate and its preferential replacement in the nucleotide-binding site with GTP, which is approximately tenfold more abundant than GDP in the cytosol.

Downstream effector signalling

The mechanistic details of how Ras proteins function in cellular signalling were lacking for much of the 1980s. At the time, however, several Ras-induced changes in cellular biochemistry had been catalogued by a number of research groups. Among the earliest of such reports came from the Feramisco laboratory in 1986, which described the activation of phospholipase A2, a calcium-dependent glycerophospholipid esterase, within minutes of the microinjection of Ras proteins into quiescent rat-embryo fibroblasts105. Other groups reported a number of similar biochemical changes that are associated with Ras expression, such as the phosphorylation of mitochondrial proteins106, the phosphorylation of plasma-membrane components107, increased diacylglycerol levels108–110, enhanced phospholipid metabolism and the activation of protein kinase C (PKC)111–113. At the time, it was not clear whether such biochemical alterations were secondary, pleiotropic effects of the forced overexpression of Ras. In 1988, Fukami and colleagues showed that antibodies that were injected against phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) inhibited Ras-induced mitogenesis114, indicating that some of the downstream biochemical responses to Ras activation are actually crucial to its cell-biological effects. Experiments such as these fuelled the search for the direct downstream signalling effectors that interact directly with Ras and mediate its various functions (FIG. 5).

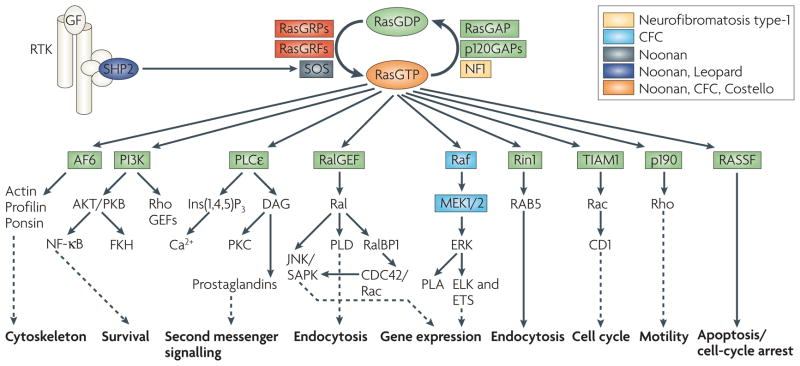

Figure 5. Ras signalling networks.

Ras proteins function as nucleotide-driven switches that relay extracellular cues to cytoplasmic signalling cascades. The binding of GTP to Ras proteins locks them in their active states, which enables high affinity interactions with downstream targets that are called effectors. Subsequently, a slow intrinsic GTPase activity cleaves off the γ-phosphate, leading to Ras functional inactivation and thus the termination of signalling. This on–off cycle is tightly controlled by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). GAPs, such as p120GAP or neurofibromin (NF1), enhance the intrinsic GTPase activity and hence negatively regulate Ras protein function. Conversely, GEFs (also known as GTP-releasing proteins/factors, termed GRPs or GRFs), such as RasGRF and son of sevenless (SOS), catalyse nucleotide ejection and therefore facilitate GTP binding and protein activation. The classical view of Ras signalling depicts Ras activation and recruitment to the plasma membrane following receptor Tyr kinase (RTK) stimulation by growth factors (GF). Activated Ras engages effector molecules — belonging to multiple effector families — that initiate several signal-transduction cascades. Outputs shown represent the main thrusts of the indicated pathways. Ras activation can also occur in endomembrane compartments, namely the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Activating mutations in the different components of the Ras–Raf–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway are associated with the indicated developmental disorders, suggesting that MAPK-signal antagonism might be a rational approach to manage certain cardio-facio-cutaneous (CFC) syndromes. AF-6, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia-1 fused gene on chromosome 6; CD1, cadherin domain-1; CDC42, cell division cycle-42; ELK, ETS-like protein; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ETS, E26-transcription factor proteins; Ins(1,4,5)P3, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; JNK, Jun N-terminal kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKB/C, protein kinase B/C; PLA/Cε/D, phospholipase A/Cε/D; RalBP1, Ral-binding protein-1; RASSF, Ras association domain-containing family; Rin1, Ras interaction/interference protein-1; SAPK, stress-activated protein kinase; SHP2, Src-homology-2 domain-containing protein Tyr phosphatase-2; TIAM1, T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-1.

The connection with RAF1 and the MAPK cascade

In 1993, four groups reported the direct interaction of Ras with the RAF1 Ser/Thr kinase, which was the first bona fide mammalian Ras effector to be identified115–118. RAF1, originally discovered through its association with avian and murine transforming retroviruses, was extensively characterized over subsequent years. This research revealed the ability of RAF1 to signal through a pathway that involves the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK), ERK1/2, and the E26-transcription factor proteins (ETS). This signalling cascade became the prototype of a number of other plasma-membrane-to-nucleus signal-transduction pathways. Interestingly, the role of MAPK signalling in Ras biology, initially described in 1992 by leevers, wood and colleagues119,120, has been characterized by several groups and shown to be both sufficient and necessary for Ras-induced transformation of murine cell lines121–124. Furthermore, the subsequent identification of B-Raf mutations in cancers, in non-overlapping frequencies with Ras mutations (for example, in melanoma and colon cancer125) emphasized an important role for aberrant Raf–MEK–ERK signalling in oncogenesis.

Ras signals through PI3K and Ral proteins

A year later, two other Ras effectors were identified: the p110 catalytic subunit of the class i phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks)126 and the guanine nucleotide-exchange factors for the Ras-like (RalA and RalB) small GTPases (Ral guanine nucleotide-dissociation stimulator (RalGDS) and RalGDS-like protein (RGL))127–129. As with Raf, PI3K activity was shown to be required for Ras transformation of NIH 3T3 cells130. Indeed, the anti-apoptotic effects of Ras were ascribed to the pro-survival activities of activated PI3K signalling through a pathway that involves the Ser/Thr kinase AKT/protein kinase B and the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), both of which have crucial roles in preventing anoikis131–133.

Initial studies of the RalGDS–Ral pathway in rodent fibroblasts indicated a limited involvement of this effector pathway in Ras-mediated cell transformation134,135. More recent studies in human cells, however, have suggested the opposite. Thus, activation of the RalGEF–Ral pathway alone, but not the PI3K or the Raf pathways, was sufficient to promote Ras transformation of human kidney epithelial cells136. Furthermore, evidence from the laboratory of Michael white has recently suggested prominent but distinct roles for the highly related RalA and RalB GTPases in regulating cellular proliferation as well as countering apoptosis, respectively137. Unresolved, however, are the mechanistic details of the downstream functions of Ral in normal and/or pathological settings.

Additional Ras effectors with diverse functions

Over the years, several other Ras effectors have been described, which include a number of proteins with diverse roles in cell physiology. These include phospholipase C-ε(PLCε), T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-1 (TIAM1), Ras interaction/interference protein-1 (RIN1), All (acute lymphoblastic leukaemia)-1 fused gene on chromosome 6 (AF-6, also known as afadin) protein, and the Ras association domain-containing family (RASSF) proteins. In 2001, PLCε was described to be a direct effector of Ras138,139. The activation of PLCε enables it to cleave Ptdins(4,5)P2 into inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), promoting the release of Ca2+ and the activation of PKC, respectively. PLCε contains a Cdc25 domain, which also places it upstream of Ras. Indeed, full length PLCε or its isolated Cdc25 domain have been shown to activate the Ras–MAPK pathway140.

TIAM1 was characterized by Channing Der’s group as a Ras effector in 2002 (REF. 141). Independently, John Collard and colleagues showed that Tiam1−/− mice exhibited resistance to Ras-induced skin carcinogenesis that was caused by 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) treatment, suggesting that TIAM1 activity is required for Ras transformation142. Of interest is the fact that the few tumours that developed in these knockout mice exhibited an elevated apoptotic index and were more invasive than those growing in wild-type mice. These findings suggest that there are potentially opposing roles for TIAM1 in the initiation, maintenance and progression of ras-driven tumours. It is worthwhile to note that mice that are deficient for RalGDS, PLCε or the p110α subunit of PI3K all exhibit impaired Ras-induced skin cancers143–145, which suggests a central role for all of these effectors in the processes of tumorigenesis.

Some of the less-characterized Ras effectors include AF-6, RIN1 and the RASSF proteins. AF-6 was identified in 1996 by Kozo Kaibuchi’s group using glutathione S-transferase (GST)–RasGTP affinity chromatography146. Subsequent sequence analysis indicated that AF-6 contains both microtubule- and actin-binding motifs, which suggested that AF-6 might participate in cytoskeletal activities downstream of Ras147. Indeed, AF-6 was found to associate with proteins that are involved in regulating cell polarity (such as ponsin and profilin) and to localize to adherens junctions148.

Ras-interacting proteins also include regulators with reported tumour-suppressor activities, such as RIN1 and the RASSF proteins. Originally identified in yeast, RIN1 was characterized as an effector for Ras in 1995 and was the first example of a downstream element that blocked Ras transformation149. The high-affinity interactions of RIN1 with Ras suggest that one of the mechanisms through which it antagonizes Ras function could be through competition with Raf. Alternative models propose a mechanism in which RIN1, which is described as a GEF for RAB5-like proteins, can trigger endocytosis of Ras-stimulating growth factor receptors, such as the eGF receptor150, thereby inhibiting Ras signalling. Recently, the RIN1 gene was found to be silenced in breast-tumour cell lines151. Indeed, re-expression of RIN1 in cells from these lines blocked anchorage-independent growth in vitro and tumour formation in vivo151.

Three members of the RASSF proteins have been characterized to date. RASSF5 (also known as NoRe1) was isolated in 1998 (REF. 152) and was later shown to possess pro-apoptotic functions153, as do RASSF1 and RASSF2 (REFS 154,155). Although the detailed mechanism of action for RASSF proteins has not been fully delineated, preliminary evidence points to the association of certain RASSF proteins with the mammalian sterile-20-like protein kinase-1 (MST1) and MST2; in D. melanogaster these kinases participate in a pathway that suppresses the activity of cyclin E and leads to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Indeed, Rassf1a-knockout mice are more susceptible to spontaneous or induced tumorigenesis156, which is consistent with the role of RASSF1A as a tumour suppressor.

A time and place for Ras activation

Mounting evidence indicates that the several Ras isoforms have differing functions in various tissues, despite a great deal of shared structural, biophysical and biochemical properties. The first evidence to support this hypothesis was derived from the association between activated RAS oncogenes and specific human cancers (TABLE 1). This association has been attributed, to a large extent, to the preferential expression of specific Ras isoforms in the affected organs157. Indeed, experiments in mouse genetics have suggested that there are distinct functions of Ras isoforms in specific tissues throughout development. For example, K-Ras-4B, but not K-Ras-4A, is essential for embryogenesis, as K-Ras-4B-deficient embryos succumbed to anaemia, liver defects and cardiac abnormalities early in gestation158,159. By contrast, H-Ras- and/or N-Ras-deficient animals develop normally and are viable160,161, which suggests that their functions are mostly dispensable or at least redundant. More recently, mice in which the H-Ras coding sequence was knocked into the locus of K-Ras (resulting in the loss of detectable K-Ras protein) were also shown to be viable162, indicating that H-Ras can functionally replace K-Ras during embryogenesis when its expression is controlled by the K-Ras promoter. Most importantly, these findings suggest that the mortality of the K-Ras-knockout mice might not result from the intrinsic inability of other Ras isoforms to compensate for K-Ras functions, but might rather derive from the inability of the other isoforms to be expressed in the same embryonic compartments as K-Ras.

The tissue-specific requirements of the various Ras isoforms might be explained by the contrasting abundance of these proteins in various tissues163. Alternatively, these requirements might be explained by the disparity in the distributions and the activation outputs of these isoforms within the intracellular membrane compartments of various cell types. For example, plasma-membrane-tethered K-Ras can induce transformation, whereas mitochondrial K-Ras induces apoptosis164. Moreover, although activated H-Ras is associated with both the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), only the ER-associated form can activate RAF1–ERK signalling165. In contrast to the ER-tethered H-Ras165, the Golgi-associated forms do not induce transformation166, suggesting that the subcellular distribution of Ras effectors determines their activation by Ras and, in turn, regulate Ras functions.

Although extensive Ras research is conducted using activated mutants of Ras proteins that are overexpressed in cellular systems, it is clear that the subcellular distribution of these overexpressed hyperactive variants might differ significantly from that of their endogenous counterparts. Indeed, much of the growth factor-induced activation of Ras is reported to occur at the plasma membrane, not at the ER or the Golgi167. Moreover, it seems that the functional activation of Ras depends on its release from lipid-raft microdomains in the plasma membrane and its redistribution to other nearby sites, enabling its physical engagement with various downstream effectors168.

Beyond oncogenesis: Ras in development

In the 1990s, the discovery that some of the well-known Ras regulators are mutated in several congenital developmental disorders suggested that aberrant Ras regulation can lead to more than oncogenic transformation. Thus, the identification of mutations in Ras regulators (such as NF1; REFS 169–171) or downstream effectors (such as Raf172) strongly indicated that deregulated Ras signalling can also cause aberrant development. Several developmental disorders, collectively known as cardio-facio-cutaneous (CFC) diseases, have been linked to Ras signalling (FIG. 5); these include neurofibromatosis type-1, Costello and Noonan syndromes.

Neurofibromatosis type-1 is a dominantly-transmitted familial cancer syndrome that is manifested by the accumulation of pigmented lesions in the skin and the eye, and by a predisposition to sporadic malignant outgrowths, such as neurofibromas, neurofibrosarcomas, phaeochromocytomas, astrocytomas and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML)173. The syndrome is caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene, which encodes neurofibromin-1, the second of the RasGAPs to be characterized71,73. Nf1-mutant mice exhibit a multitude of abnormalities, including cardiovascular, haematopoietic and neural crest defects174,175. Although expression of the RasGAP domain of NF1 in these mice rescued the cardiac and haematopoietic defects, it did not rescue the neural crest overgrowth, and mice died in utero176. This suggests a causative role for the NF1–Ras axis in regulating developmental processes, at least in selected cell lineages of the developing embryo.

PTPN11 encodes Src-homology-2 domain-containing protein Tyr phosphatase-2 (SHP2), a non-receptor protein Tyr phosphatase that has a key role in conveying upstream growth factor signals to Ras177. Mutations in PTPN11 account for ~50% of Noonan syndrome cases178 and are gain-of-function mutations that mostly deregulate the phosphatase activity and the substrate specificity179 of SHP2. The syndrome is characterized by skeletal abnormalities, learning disabilities, cardiac defects and symptoms that are consistent with JMML180. Moreover, a direct causal link between PTPN11 mutations and Ras signalling can be found in JMML. First, activating mutations in PTPN11 cause deregulated ERK signalling and abnormal myeloid colony growth in vitro181. Second, activating PTPN11 mutations are found in ~35% of cases of JMML, and the mouse model of Noonan syndrome (where the activated Asp61Gly-Ptpn11 gene is expressed from the Ptpn11 endogenous promoter) is also characterized by increased ERK activation182. Third, K-Ras-mutant mice develop JMML-like abnormalities and a significant number of human cases with JMML exhibit mutations in K-RAS183. It is noteworthy that PTPN11 mutations also cause LEOPARD syndrome, a disease that is characterized by cardiac and visual abnormalities, pulmonary stenosis, stunted growth and partial deafness184. However, the involvement of Ras signalling in this syndrome has not yet been validated.

Costello syndrome is another CFC disease that is characterized by craniofacial abnormalities, impaired cardiac development and an increased predisposition to specific tumours, such as ganglioneuroblastomas, bladder carcinomas and rhabdomyosarcomas185. The germline mutations that are associated with Costello syndrome mostly involve activating H-RAS mutations that affect codons 12, 13, 117 and 148. The most frequent lesion is the Gly12Ser mutation, which activates Ras, but to levels below those seen in the tumour-associated Gly12Val mutation186.

Ras mutations have also been found in a subset of Noonan patients who do not harbour PTPN11 mutations. These lesions are restricted to K-RAS and target residues Val14, Thr58, Val152, Asp153 and Phe156, all of which are thought to cause moderate upregulation of Ras activity187. Other types of mutations that are found in patients with Noonan syndrome are SOS1 mutations. These lesions are typically found within the Cdc25-regulatory DBl homology (DH) and/or pleckstrin homology (PH) domains and are thought to relieve the auto-inhibition that is imposed by the DH/PH domains on the RasGEF motif. Indeed, recent expression studies showed that Ras activation is elevated in cells that overexpress these SOS1 mutants188.

Antagonism of Ras: where are we?

The crucial role of prenylation in the cellular functions of Ras proteins has made the enzymes that catalyse the post-translational processing of Ras prime targets for rational drug design or compound-screening methodologies (FIG. 2). The first of such approaches adopted molecular mimicry, in which farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) that simulate the CAAX motif were used to compete with Ras for its post-translational processing enzymes, thus blocking the first step of Ras modification and thereby inhibiting its activity. Indeed, in vivo studies that were conducted with these inhibitors in 1995 were very promising, as FTIs caused regression of mouse mammary tumour virus-H-ras mammary carcinomas with no detectable systemic toxicity189.

Although promising in principle, the FTI strategy has been hindered by two interrelated problems. Unlike H-Ras, both N-Ras and K-Ras were shown to become geranylgeranylated at their C termini following FTI treatment (and inhibition of FTase activity), which rendered them refractory to inactivation by FTIs190. In addition, despite the success of FTIs in antagonizing N-Ras- and K-Ras-driven transformation191–193, this function was later attributed to the ability of FTIs to inhibit the functions of other prenylated cellular proteins, such as Rheb (Ras homologue enriched in the brain), RhoB and the centromeric proteins CeNP-E or CeNP-F194–197. These problems forced the development of alternative strategies to block Ras function.

Pharmacological inhibition of other steps of the Ras processing pathway have targeted the enzymes RCE1 and ICMT1. Although reports in the early 1990s suggested that blocking the proteolytic cleavage of Ras was not sufficient to inhibit its functions198,199, more recent studies in mice suggested that Ras transformation is impaired in Rce-deficient animals. Indeed, conditional disruption of the Rce1 allele caused ~50% reduction in the membrane-bound fraction of K-Ras and H-Ras, which is consistent with reduced xenograft tumour growth200. A similar approach was used to target ICMT1, causing a partial reduction in membrane association of K-Ras, which corresponded to the loss of its tumour-forming ability201. Of note, drugs that inhibit ICMT1, such as methotrexate or cysmethynil, show effectiveness in tissue culture and animal models202,203. However, in light of the extensive number of other CAAX-terminating proteins that serve as substrates for these two enzymes, in particular RhoGTPases, the selective and targeted nature of these approaches for Ras proteins remains unclear.

Over the years, more approaches have been developed to antagonize Ras functions in vivo. These include the inhibition of Ras expression by anti-sense RNA-based technology204, the use of anti-Ras ribozymes (hammerhead models; see REFS 205–207), or application of anti-Ras reoviral therapy208,209. A significant effort has been made to develop low-molecular-weight chemical inhibitors of the downstream effectors of Ras, notably the Raf–MEK–ERK cascade (for example, Sorafenib210 or CI-1040/PD184352, REF. 211). The long term future of these development efforts is hindered by difficulties in the mode of administration of such agents, their therapeutic index and their ability to durably suppress Ras activity in vivo.

Outlook

The advances achieved over the past 30 years have illuminated important details of the involvement of Ras in nearly every aspect of normal and aberrant cell physiology. Much of this knowledge has been gained using experimental approaches that relied primarily on forced overexpression of activated Ras proteins or total ablation of Ras activity in cellular systems. However, it is increasingly appreciated that ectopically expressed Ras proteins are often produced at aberrantly high levels and are often mis-localized to various subcellular sites. As such, it is imperative to revisit some of the fundamental questions regarding Ras function using experimental approaches that can more accurately mimic physiological levels of Ras expression. In addition, attention should be given to isoform-specific Ras signalling and to the question of how membrane micro-domains and cytoplasmic compartments determine the coupling of Ras to its effectors and downstream signalling pathways.

Finally, although much of the emphasis has been placed on H-, K- and N-Ras proteins, more attention must be focused on other, less-characterized family members, such as M-Ras and R-Ras, which are likely to reveal further novel insights into Ras biology. Similarly, additional effort is required to understand the full range of immediate downstream effectors of Ras beyond the canonical MAPK, PI3K and Ral proteins. With this expanding knowledge comes the hope that we might finally be able to exploit our knowledge of Ras biology for the development of truly effective therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Der for comments on the manuscript and G. Bell for help in structural configurations. The authors’ research is supported, in part, by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (R.A.W), National Institues of Health (NIH) P01 CA08111 (R.A.W.), NIH U54 CA12515 (R.A.W.), NIH SPORE P50 CA089393 (R.A.W.), Susan Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (A.E.K.), Harvard Specialized Program for Research Excellence (A.E.K.), Whitehead Institute-Genzyme fellowship (A.E.K.) and the Ludwig Center for Molecular Oncology at Massachusetts Institue of Technology, USA.

Glossary

- Rous sarcoma virus (RSV)

A retrovirus that was discovered in 1916 by Peyton rous by injecting a cell-free extract of chicken tumour into healthy chickens. The extract was found to induce oncogenesis in Plymouth rock chickens

- G proteins

A family of proteins involved in second messenger cascades. They function as molecular switches, alternating between an inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound state

- GTPase-activating protein

(GAP), A protein that stimulates the intrinsic ability of a GTPase to hydrolyse GTP to GDP. Therefore, GAPs negatively regulate GTPases by converting them from active (GTP bound) to inactive (GDP bound)

- Guanine nucleotide-exchange factor

(GEF), A protein that facilitates the exchange of GDP for GTP in the nucleotide-binding pocket of a GTP-binding protein

- Anoikis

The induction of programmed cell death by the detachment of cells from the extracellular matrix

- Lipid raft

A membrane microdomain that is enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids and lipid-modified proteins, such as glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked proteins and palmitoylated proteins. These microdomains often function as platforms for signalling events

- Cardio-facio-cutaneous diseases

Congenital developmental disorders caused by disregulated ras signalling. These diseases are characterized by the accumulation of sporadic tumours as well as skeletal, cardiac and visual abnormalities

- Neural crest

A group of embryonic cells that separate from the embryonic neural plate and migrate, giving rise to the spinal and autonomic ganglia, peripheral glia, chromaffin cells, melanocytes and some haematopoietic cells

Footnotes

DATABASES

ProteinDataBank: http://www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do

1bkd | 1wq1 | 4q21 | 5p21

FirstGlance in Jmol (3D structures): http://molvis.sdsc.edu/fgij/index.htm

1bkd | 1wq1 | 4q21 | 5p21

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

E1A | Ha-ras | Ki-ras | myc | N-ras | NF1 | PTPN11 | RIN1 | SV40 large T antigen | Tiam1

Interpro: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro

Cdc25 | DH | PH | SH2 | SH3

OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM

Costello syndrome | JMML | LEOPARD syndrome | neurofibromatosis type-1 syndrome | Noonan syndrome

UniProtKB: http://ca.expasy.org/sprot

AKT | B-Raf | Cdc25 | EGF | ERK | GRB2 | H-Ras | ICMT1 | MAPK | MST1 | MST2 | NF1 | N-Ras | PKC | PLCε | RAF1 | RalGDS | RasGAP | RASSF1 | RASSF2 | RASSF5 | RCE1 | Rheb | RhoB | RIN1 | RGL | SHP2 | SOS | TIAM1

FURTHER INFORMATION

Robert Weinberg’s homepage: http://www.wi.mit.edu/research/faculty/weinberg.html

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

Contributor Information

Antoine E. Karnoub, Email: karnoub@wi.mit.edu.

Robert A. Weinberg, Email: weinberg@wi.mit.edu.

References

- 1.DeFeo D, et al. Analysis of two divergent rat genomic clones homologous to the transforming gene of Harvey murine sarcoma virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3328–3332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis RW, DeFeo D, Furth ME, Scolnick EM. Mouse cells contain two distinct ras gene mRNA species that can be translated into a p21 onc protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1339–1345. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.11.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang EH, Gonda MA, Ellis RW, Scolnick EM, Lowy DR. Human genome contains four genes homologous to transforming genes of Harvey and Kirsten murine sarcoma viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4848–4852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.16.4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stehelin D, Varmus HE, Bishop JM, Vogt PK. DNA related to the transforming gene(s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA. Nature. 1976;260:170–173. doi: 10.1038/260170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parada LF, Tabin CJ, Shih C, Weinberg RA. Human EJ bladder carcinoma oncogene is homologue of Harvey sarcoma virus ras gene. Nature. 1982;297:474–478. doi: 10.1038/297474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Der CJ, Krontiris TG, Cooper GM. Transforming genes of human bladder and lung carcinoma cell lines are homologous to the ras genes of Harvey and Kirsten sarcoma viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3637–3640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos E, Tronick SR, Aaronson SA, Pulciani S, Barbacid M. T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene is an activated form of the normal human homologue of BALB- and Harvey-MSV transforming genes. Nature. 1982;298:343–347. doi: 10.1038/298343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabin CJ, et al. Mechanism of activation of a human oncogene. Nature. 1982;300:143–149. doi: 10.1038/300143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy EP, Reynolds RK, Santos E, Barbacid M. A point mutation is responsible for the acquisition of transforming properties by the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene. Nature. 1982;300:149–152. doi: 10.1038/300149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taparowsky E, et al. Activation of the T24 bladder carcinoma transforming gene is linked to a single amino acid change. Nature. 1982;300:762–765. doi: 10.1038/300762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capon DJ, Chen EY, Levinson AD, Seeburg PH, Goeddel DV. Complete nucleotide sequences of the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene and its normal homologue. Nature. 1983;302:33–37. doi: 10.1038/302033a0. References 6–11 established that oncogenic activation of Ras is caused by point mutations of the endogenous gene. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu K, et al. Three human transforming genes are related to the viral ras oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall A, Marshall CJ, Spurr NK, Weiss RA. Identification of transforming gene in two human sarcoma cell lines as a new member of the ras gene family located on chromosome 1. Nature. 1983;303:396–400. doi: 10.1038/303396a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taparowsky E, Shimizu K, Goldfarb M, Wigler M. Structure and activation of the human N-ras gene. Cell. 1983;34:581–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray MJ, et al. The HL-60 transforming sequence: a ras oncogene coexisting with altered myc genes in hematopoietic tumors. Cell. 1983;33:749–757. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newbold RF, Overell RW. Fibroblast immortality is a prerequisite for transformation by EJ c-Ha-ras oncogene. Nature. 1983;304:648–651. doi: 10.1038/304648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1983;304:596–602. doi: 10.1038/304596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruley HE. Adenovirus early region 1A enables viral and cellular transforming genes to transform primary cells in culture. Nature. 1983;304:602–606. doi: 10.1038/304602a0. References 16–18 proposed the notion that multiple pathways are required for cellular transformation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhim JS, et al. Neoplastic transformation of human epidermal keratinocytes by AD12-SV40 and Kirsten sarcoma viruses. Science. 1985;227:1250–1252. doi: 10.1126/science.2579430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoakum GH, et al. Transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells transfected by Harvey ras oncogene. Science. 1985;227:1174–1179. doi: 10.1126/science.3975607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yancopoulos GD, et al. N-myc can cooperate with ras to transform normal cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5455–5459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos E, et al. Malignant activation of a K-ras oncogene in lung carcinoma but not in normal tissue of the same patient. Science. 1984;223:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.6695174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano H, et al. Isolation of transforming sequences of two human lung carcinomas: structural and functional analysis of the activated c-K-ras oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:71–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirai H, et al. Activation of the c-K-ras oncogene in a human pancreas carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;127:168–174. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(85)80140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hand PH, et al. Monoclonal antibodies of predefined specificity detect activated ras gene expression in human mammary and colon carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5227–5231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita J, et al. Ha-ras oncogenes are activated by somatic alterations in human urinary tract tumours. Nature. 1984;309:464–466. doi: 10.1038/309464a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gambke C, Signer E, Moroni C. Activation of N-ras gene in bone marrow cells from a patient with acute myeloblastic leukaemia. Nature. 1984;307:476–478. doi: 10.1038/307476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gambke C, Hall A, Moroni C. Activation of an N-ras gene in acute myeloblastic leukemia through somatic mutation in the first exon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:879–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos JL, et al. Amino-acid substitutions at codon 13 of the N-ras oncogene in human acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 1985;315:726–730. doi: 10.1038/315726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen JW, Steenvoorden AC, Collard JG, Nusse R. Oncogene activation in human myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 1985;45:3262–3267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sklar MD, Kitchingman GR. Isolation of activated ras transforming genes from two patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padua RA, Barrass NC, Currie GA. Activation of N-ras in a human melanoma cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:582–585. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.3.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukumar S, Notario V, Martin-Zanca D, Barbacid M. Induction of mammary carcinomas in rats by nitroso-methylurea involves malignant activation of H-ras-1 locus by single point mutations. Nature. 1983;306:658–661. doi: 10.1038/306658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balmain A, Pragnell IB. Mouse skin carcinomas induced in vivo by chemical carcinogens have a transforming Harvey-ras oncogene. Nature. 1983;303:72–74. doi: 10.1038/303072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balmain A, Ramsden M, Bowden GT, Smith J. Activation of the mouse cellular Harvey-ras gene in chemically induced benign skin papillomas. Nature. 1984;307:658–660. doi: 10.1038/307658a0. References 33–35 indicated that chemical carcinogenesis caused mutations of ras sequences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerrero I, Calzada P, Mayer A, Pellicer A. A molecular approach to leukemogenesis: mouse lymphomas contain an activated c-ras oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:202–205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerrero I, Villasante A, Corces V, Pellicer A. Activation of a c-K-ras oncogene by somatic mutation in mouse lymphomas induced by γ radiation. Science. 1984;225:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.6474169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuki K, Nose K, Okamoto H, Tsuchida N, Hayashi K. Amplification of c-Ki-ras gene and aberrant expression of c-myc in WI-38 cells transformed in vitro by γ-irradiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;128:1037–1043. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shih TY, Papageorge AG, Stokes PE, Weeks MO, Scolnick EM. Guanine nucleotide-binding and autophosphorylating activities associated with the p21src protein of Harvey murine sarcoma virus. Nature. 1980;287:686–691. doi: 10.1038/287686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGrath JP, Capon DJ, Goeddel DV, Levinson AD. Comparative biochemical properties of normal and activated human ras p21 protein. Nature. 1984;310:644–649. doi: 10.1038/310644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibbs JB, Sigal IS, Poe M, Scolnick EM. Intrinsic GTPase activity distinguishes normal and oncogenic ras p21 molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5704–5708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweet RW, et al. The product of ras is a GTPase and the T24 oncogenic mutant is deficient in this activity. Nature. 1984;311:273–275. doi: 10.1038/311273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark R, Wong G, Arnheim N, Nitecki D, McCormick F. Antibodies specific for amino acid 12 of the ras oncogene product inhibit GTP binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5280–5284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Der CJ, Finkel T, Cooper GM. Biological and biochemical properties of human rasH genes mutated at codon 61. Cell. 1986;44:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trahey M, McCormick F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science. 1987;238:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.2821624. References 41–46 established that oncogenic mutation of ras affects its nucleotide cycle. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shih TY, et al. Identification of a precursor in the biosynthesis of the p21 transforming protein of harvey murine sarcoma virus. J Virol. 1982;42:253–261. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.1.253-261.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sefton BM, Trowbridge IS, Cooper JA, Scolnick EM. The transforming proteins of Rous sarcoma virus, Harvey sarcoma virus and Abelson virus contain tightly bound lipid. Cell. 1982;31:465–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willumsen BM, Christensen A, Hubbert NL, Papageorge AG, Lowy DR. The p21 ras C-terminus is required for transformation and membrane association. Nature. 1984;310:583–586. doi: 10.1038/310583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willumsen BM, Norris K, Papageorge AG, Hubbert NL, Lowy DR. Harvey murine sarcoma virus p21 ras protein: biological and biochemical significance of the cysteine nearest the carboxy terminus. EMBO J. 1984;3:2581–2585. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srivastava SK, Lacal JC, Reynolds SH, Aaronson SA. Antibody of predetermined specificity to a carboxy-terminal region of H-ras gene products inhibits their guanine nucleotide-binding function. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3316–3319. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casey PJ, Solski PA, Der CJ, Buss JE. p21ras is modified by a farnesyl isoprenoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8323–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schafer WR, et al. Genetic and pharmacological suppression of oncogenic mutations in ras genes of yeast and humans. Science. 1989;245:379–385. doi: 10.1126/science.2569235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiss Y, Goldstein JL, Seabra MC, Casey PJ, Brown MS. Inhibition of purified p21ras farnesyl: protein transferase by Cys-AAX tetrapeptides. Cell. 1990;62:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schaber MD, et al. Polyisoprenylation of Ras in vitro by a farnesyl-protein transferase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14701–14704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schafer WR, et al. Enzymatic coupling of cholesterol intermediates to a mating pheromone precursor and to the ras protein. Science. 1990;249:1133–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.2204115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hancock JF, Paterson H, Marshall CJ. A polybasic domain or palmitoylation is required in addition to the CAAX motif to localize p21ras to the plasma membrane. Cell. 1990;63:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90294-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamata T, Feramisco JR. Epidermal growth factor stimulates guanine nucleotide binding activity and phosphorylation of ras oncogene proteins. Nature. 1984;310:147–150. doi: 10.1038/310147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mulcahy LS, Smith MR, Stacey DW. Requirement for ras proto-oncogene function during serum-stimulated growth of NIH 3T3 cells. Nature. 1985;313:241–243. doi: 10.1038/313241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hagag N, Halegoua S, Viola M. Inhibition of growth factor-induced differentiation of PC12 cells by microinjection of antibody to ras p21. Nature. 1986;319:680–682. doi: 10.1038/319680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campisi J, Gray HE, Pardee AB, Dean M, Sonenshein GE. Cell-cycle control of c-myc but not c-ras expression is lost following chemical transformation. Cell. 1984;36:241–247. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Samid D, Schaff Z, Chang EH, Friedman RM. Interferon-induced modulation of human ras oncogene expression. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;192:265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emanoil-Ravier R, et al. Interferon-mediated regulation of myc and Ki-ras oncogene expression in long-term-treated murine viral transformed cells. J Interferon Res. 1985;5:613–619. doi: 10.1089/jir.1985.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Samid D, Chang EH, Friedman RM. Development of transformed phenotype induced by a human ras oncogene is inhibited by interferon. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;126:509–516. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Korn LJ, Siebel CW, McCormick F, Roth RA. Ras p21 as a potential mediator of insulin action in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1987;236:840–843. doi: 10.1126/science.3554510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hurley JB, Simon MI, Teplow DB, Robishaw JD, Gilman AG. Homologies between signal transducing G proteins and ras gene products. Science. 1984;226:860–862. doi: 10.1126/science.6436980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibbs JB, Schaber MD, Allard WJ, Sigal IS, Scolnick EM. Purification of ras GTPase activating protein from bovine brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5026–5030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vogel US, et al. Cloning of bovine GAP and its interaction with oncogenic ras p21. Nature. 1988;335:90–93. doi: 10.1038/335090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trahey M, et al. Molecular cloning of two types of GAP complementary DNA from human placenta. Science. 1988;242:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.3201259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molloy CJ, et al. PDGF induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of GTPase activating protein. Nature. 1989;342:711–714. doi: 10.1038/342711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu GF, et al. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell. 1990;62:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ballester R, et al. The NF1 locus encodes a protein functionally related to mammalian GAP and yeast IRA proteins. Cell. 1990;63:851–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martin GA, et al. The GAP-related domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product interacts with ras p21. Cell. 1990;63:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90150-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wallace MR, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science. 1990;249:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2134734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Robinson LC, Gibbs JB, Marshall MS, Sigal IS, Tatchell K. CDC25: a component of the RAS-adenylate cyclase pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1987;235:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.3547648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Broek D, et al. The S. cerevisiae CDC25 gene product regulates the RAS/adenylate cyclase pathway. Cell. 1987;48:789–799. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolfman A, Macara IG. A cytosolic protein catalyzes the release of GDP from p21ras. Science. 1990;248:67–69. doi: 10.1126/science.2181667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Downward J, Riehl R, Wu L, Weinberg RA. Identification of a nucleotide exchange-promoting activity for p21ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5998–6002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.West M, Kung HF, Kamata T. A novel membrane factor stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange reaction of ras proteins. FEBS Lett. 1990;259:245–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80019-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wei W, et al. Identification of a mammalian gene structurally and functionally related to the CDC25 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7100–7104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shou C, Farnsworth CL, Neel BG, Feig LA. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding a guanine-nucleotide-releasing factor for Ras p21. Nature. 1992;358:351–354. doi: 10.1038/358351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bowtell D, Fu P, Simon M, Senior P. Identification of murine homologues of the Drosophila son of sevenless gene: potential activators of ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6511–6515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gale NW, Kaplan S, Lowenstein EJ, Schlessinger J, Bar-Sagi D. Grb2 mediates the EGF-dependent activation of guanine nucleotide exchange on Ras. Nature. 1993;363:88–92. doi: 10.1038/363088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li N, et al. Guanine-nucleotide-releasing factor hSos1 binds to Grb2 and links receptor tyrosine kinases to Ras signalling. Nature. 1993;363:85–88. doi: 10.1038/363085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rozakis-Adcock M, Fernley R, Wade J, Pawson T, Bowtell D. The SH2 and SH3 domains of mammalian Grb2 couple the EGF receptor to the Ras activator mSos1. Nature. 1993;363:83–85. doi: 10.1038/363083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Egan SE, et al. Association of Sos Ras exchange protein with Grb2 is implicated in tyrosine kinase signal transduction and transformation. Nature. 1993;363:45–51. doi: 10.1038/363045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buday L, Downward J. Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell. 1993;73:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90146-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bernards A. GAPs galore! A survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1603:47–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Geyer M, Wittinghofer A. GEFs, GAPs, GDIs and effectors: taking a closer (3D) look at the regulation of Ras-related GTP-binding proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:786–792. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tucker J, et al. Expression of p21 proteins in Escherichia coli and stereochemistry of the nucleotide-binding site. EMBO J. 1986;5:1351–1358. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Itoh H, et al. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of cDNAs for α subunits of the guanine nucleotide-binding proteins Gs, Gi, and Go from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3776–3780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clanton DJ, Hattori S, Shih TY. Mutations of the ras gene product p21 that abolish guanine nucleotide binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5076–5080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Der CJ, Pan BT, Cooper GM. rasH mutants deficient in GTP binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3291–3294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lacal JC, Anderson PS, Aaronson SA. Deletion mutants of Harvey ras p21 protein reveal the absolute requirement of at least two distant regions for GTP-binding and transforming activities. EMBO J. 1986;5:679–687. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sigal IS, Gibbs JB, D’Alonzo JS, Scolnick EM. Identification of effector residues and a neutralizing epitope of Ha-ras-encoded p21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4725–4729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stone JC, Vass WC, Willumsen BM, Lowy DR. p21-ras effector domain mutants constructed by “cassette” mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3565–3569. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pai EF, et al. Structure of the guanine-nucleotide-binding domain of the Ha-ras oncogene product p21 in the triphosphate conformation. Nature. 1989;341:209–214. doi: 10.1038/341209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brunger AT, et al. Crystal structure of an active form of RAS protein, a complex of a GTP analog and the HRAS p21 catalytic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4849–4853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Milburn MV, et al. Molecular switch for signal transduction: structural differences between active and inactive forms of protooncogenic ras proteins. Science. 1990;247:939–945. doi: 10.1126/science.2406906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schlichting I, et al. Time-resolved X-ray crystallographic study of the conformational change in Ha-Ras p21 protein on GTP hydrolysis. Nature. 1990;345:309–315. doi: 10.1038/345309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tong LA, et al. Structural differences between a ras oncogene protein and the normal protein. Nature. 1989;337:90–93. doi: 10.1038/337090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Krengel U, et al. Three-dimensional structures of H-ras p21 mutants: molecular basis for their inability to function as signal switch molecules. Cell. 1990;62:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90018-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Scheffzek K, et al. The Ras–RasGAP complex: structural basis for GTPase activation and its loss in oncogenic Ras mutants. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boriack-Sjodin PA, Margarit SM, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J. The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos. Nature. 1998;394:337–343. doi: 10.1038/28548. References 97–104 described the structural details of Ras activation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bar-Sagi D, Feramisco JR. Induction of membrane ruffling and fluid-phase pinocytosis in quiescent fibroblasts by ras proteins. Science. 1986;233:1061–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.3090687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]