Abstract

Many types of cancer, including glioma, melanoma, NSCLC, among others, are resistant to apoptosis induction and poorly responsive to current therapies with propaptotic agents. We describe a series of 2,3-disubstituted indoles, which display cytostatic rather than cytotoxic effects in cancer cells, and serve as a new chemical scaffold to develop anticancer agents capable of combating apoptosis-resistant cancers associated with dismal prognoses.

Keywords: cancer, apoptosis resistance, indole, antiproliferative

Apoptosis-resistant cancers represent a major challenge in the clinic as most of the currently available chemotherapeutic agents work through the induction of apoptosis and, therefore, provide very limited therapeutic benefits for the patients affected by these malignancies. Such apoptosis-resistant cancers include the tumors of the lung, liver, stomach, esophagus, pancreas as well as melanomas and gliomas.1 For example, patients afflicted by a type of gliomas, known as glioblastoma multiforme,2,3 have a median survival expectancy of less than 14 months when treated with a standard protocol of surgical resection, radiotherapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide.4 Because these glioma cells display resistance to apoptosis, they respond poorly to conventional chemotherapy with proapoptotic agents.3,5

In addition, it must be recalled that 90% of cancer patients die from tumor metastases6 and that metastatic cancer cells have acquired resistance to a process termed anoikis, i.e. cell death resulting from losing contact with extracellular matrix or neighboring cells.6 This phenomenon results in apoptosis resistance by metastatic cells making them unresponsive to a large majority of proapoptotic agents as well.3,7–9 One solution to apoptosis resistance entails the complementation of cytotoxic therapeutic regimens with cytostatic agents and thus a search for novel cytostatic anticancer drugs that can overcome cancer cell resistance to apoptosis is an important pursuit.10–13

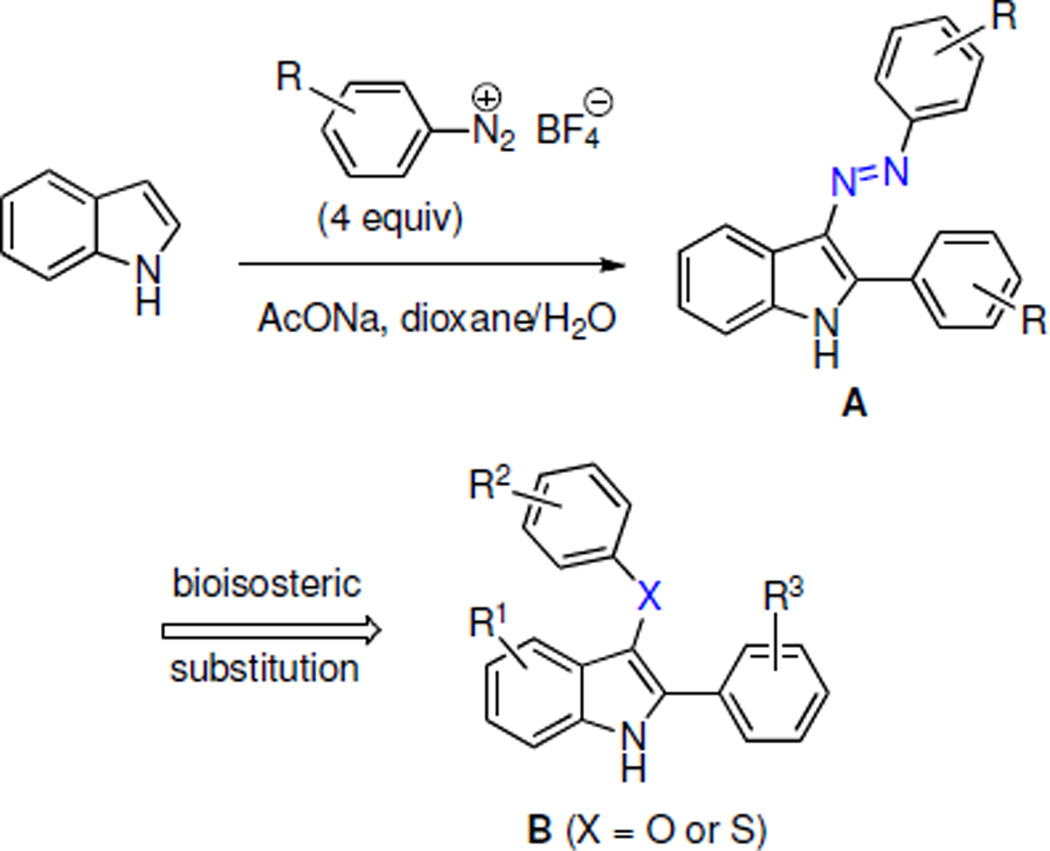

Recently we described a series of 2-aryl-3-azoindoles A as antibacterial agents active against MRSA (Scheme 1).14 We showed that the metabolically labile azo group could be bioisosterically replaced by an ether or thioether functionalities leading to structures B, which were potent antibacterial agents as well. Unfortunately, these compounds were also found to inhibit the growth of human cervical cancer cells HeLa at comparable concentrations and this diminished our interest in pursuing them as novel antibacterials. However, during the antiproliferative assays, we noticed that these compounds do not kill cancer cells at GI50-related concentrations, but rather display cytostatic effects. This observation prompted our efforts to investigate the compounds of this type as a new class of cytostatic agents potentially useful in the treatment of apoptosis-resistant cancers.

Scheme 1.

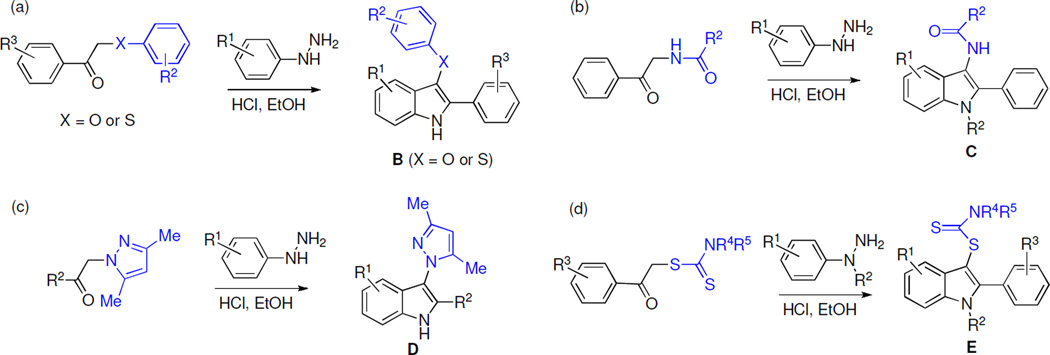

Because the antiproliferative effects of indoles A and B were similar, we surmised that the position C-3 of the indole ring can tolerate structurally diverse substituents. Previously, we developed synthetic pathways based on the Fisher indole reaction, which in addition to C-3 ether and thioether indoles B (Scheme 2a) can be used to prepare C-3 amide indoles C (Scheme 2b), C-3 pyrazole indoles D (Scheme 2c) and C-3 dithiocarbamate indoles E (Scheme 2d).15–18 Using this chemistry, a number of C-3 analogues of each structural type were synthesized and their structures are shown in Table 1.

Scheme 2.

Table 1.

Structures of C-3 derivatized 2-arylindoles and their antiproliferative activities toward cancer cells.

| # | structure | GI50

in vitro values (μM)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U373 | Hs683 | A549 | SKMEL | B16 | ||

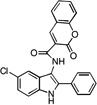

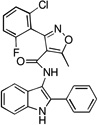

| A1 |  |

33 | 31 | 26 | 33 | 33 |

| A2 |  |

30 | 24 | 23 | 31 | 26 |

| B1 |  |

13 | 13 | 10 | 19 | 10 |

| B2 |  |

20 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 14 |

| B3 |  |

35 | 26 | 30 | 28 | 29 |

| B4 |  |

25 | 28 | 25 | 28 | 29 |

| B5 |  |

50 | 54 | 59 | 57 | 31 |

| B6 |  |

8 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| B7 |  |

35 | 24 | 28 | 28 | 20 |

| B8 |  |

28 | 31 | 27 | 34 | 28 |

| B9 |  |

24 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 35 |

| B10 |  |

28 | 31 | 27 | 34 | 28 |

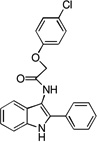

| C1 |  |

66 | 45 | 37 | 55 | 27 |

| C2 |  |

24 | 15 | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| C3 |  |

38 | 69 | 38 | 67 | 44 |

| C4 |  |

47 | 33 | 30 | 30 | 35 |

| C5 |  |

66 | 38 | 37 | 48 | 32 |

| D1 |  |

47 | 32 | 29 | 31 | 39 |

| D2 |  |

10 | 29 | 26 | 33 | 40 |

| D3 |  |

32 | 32 | 40 | 35 | 36 |

| D4 |  |

43 | 50 | 42 | 46 | 65 |

| D5 |  |

84 | 67 | 61 | 84 | >100 |

| D6 |  |

90 | 58 | 38 | 80 | 73 |

| E1 |  |

43 | 32 | 31 | 35 | 20 |

| E2 |  |

33 | 36 | 34 | 39 | 21 |

| E3 |  |

68 | 34 | 37 | 52 | 37 |

| E4 |  |

39 | 31 | 29 | 34 | 37 |

| E5 |  |

>100 | 85 | 72 | 78 | 50 |

| E6 |  |

9 | 22 | 22 | 29 | 33 |

| E7 |  |

36 | 26 | 31 | 28 | 40 |

| E8 |  |

32 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 29 |

| E9 |  |

35 | 36 | 34 | 36 | 27 |

U373 (ECACC code 89081403) cell line was cultured in MEM medium supplemented with 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum; Hs683 (ATCC code HTB-138), SKMEL-28 (ATCC code HTB-72), A549 (DSMZ code ACC107) and B16F10 (ATCC code CRL-6475) cell lines were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum; MEM and RPMI cell culture media were supplemented with 4mM glutamine, 100μg/mL gentamicin and penicillin-streptomycin (200U/mL and 200μg/mL).

The synthesized compounds were evaluated for in vitro growth inhibition using the MTT colorimetric assay19 against a panel of five cancer cell lines including those resistant to proapoptotic stimuli [human U373 glioblastoma,20 human A549 non-small-cell-lung cancer (NSCLC),21 and human SKMEL-28 melanoma22] as well as apoptosis-sensitive tumor models [human Hs683 anaplastic oligodendroglioma20 and mouse B16F10 melanoma22]. Analysis of the data shown in Table 1 reveals that most of the synthesized compounds exhibit antiproliferative properties in the double-digit micromolar region and do not drastically differ in their potencies. Indeed, it appears that the position C-3 of the indole ring tolerates diverse substitution in this type of structure. Yet, C-3 ether and thioether indoles B appear to the most potent, with ether indole B6 exhibiting single-digit micromolar GI50 values. Importantly, all synthesized 2,3-disubstituted indoles do not discriminate between the cancer cell lines based on the apoptosis sensitivity criterion and display comparable potencies in both cell types, further indicating that apoptosis induction may not the primary mechanism responsible for antiproliferative activity in this series of compounds, at least in solid cancers.

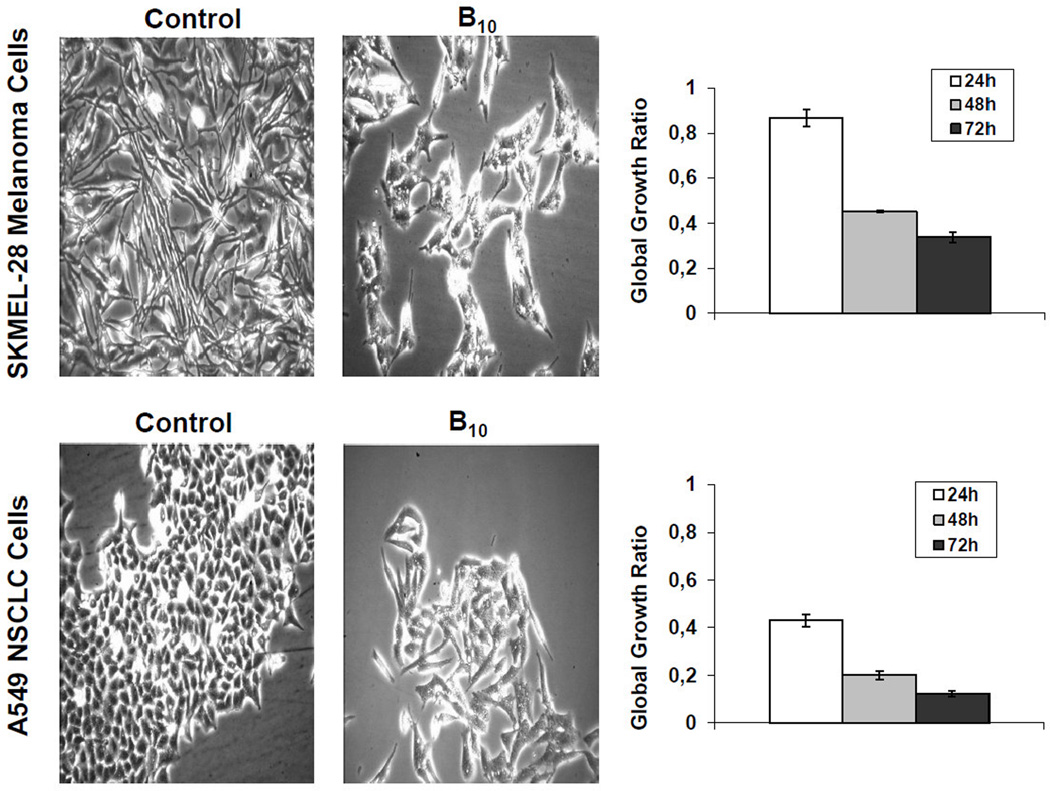

We also employed computer-assisted phase-contrast microscopy10,22 (quantitative videomicroscopy) to analyze the principal mechanism of action associated with indoles’ B in vitro growth inhibitory effects, as first revealed by the MTT colorimetric assay. Figure 1 shows that indole B10 inhibits cancer cell proliferation without inducing cell death when assayed at its GI50 concentrations (Table 1) in SKMEL-28 melanoma and A549 NSCLC cells. Based on the phase contrast pictures obtained by means of quantitative videomicroscopy, we calculated the global growth ratio (GGR), which corresponds to the ratio of the mean number of cells present in a given image captured in the experiment (in this case after 24, 48 and 72 h) to the number of cells present in the first image (at 0 h). We divided this ratio obtained in the B10-treated experiment by the ratio obtained in the control. The GGR values of 0.1 and 0.3 correspondingly in these two cell lines indicate that 10 and 30% of cells grew in the B10-treated experiment as compared to the control over a 72 h observation period. Thus, the GGR calculations confirm the MTT colorimetric data in Table 1, i.e. 30 µM B10 exhibits marked growth inhibitory activity in SKMEL-28 and A549 cells, which display resistance to apoptosis induction.

Figure 1.

Cellular imaging of B10 against melanoma SKMEL-28 and NSCLC A549 cells illustrating non-cytotoxic, but cytostatic, antiproliferative mechanism at MTT colorimetric assay-related GI50 concentrations after 72 h of cell culture with the drug.

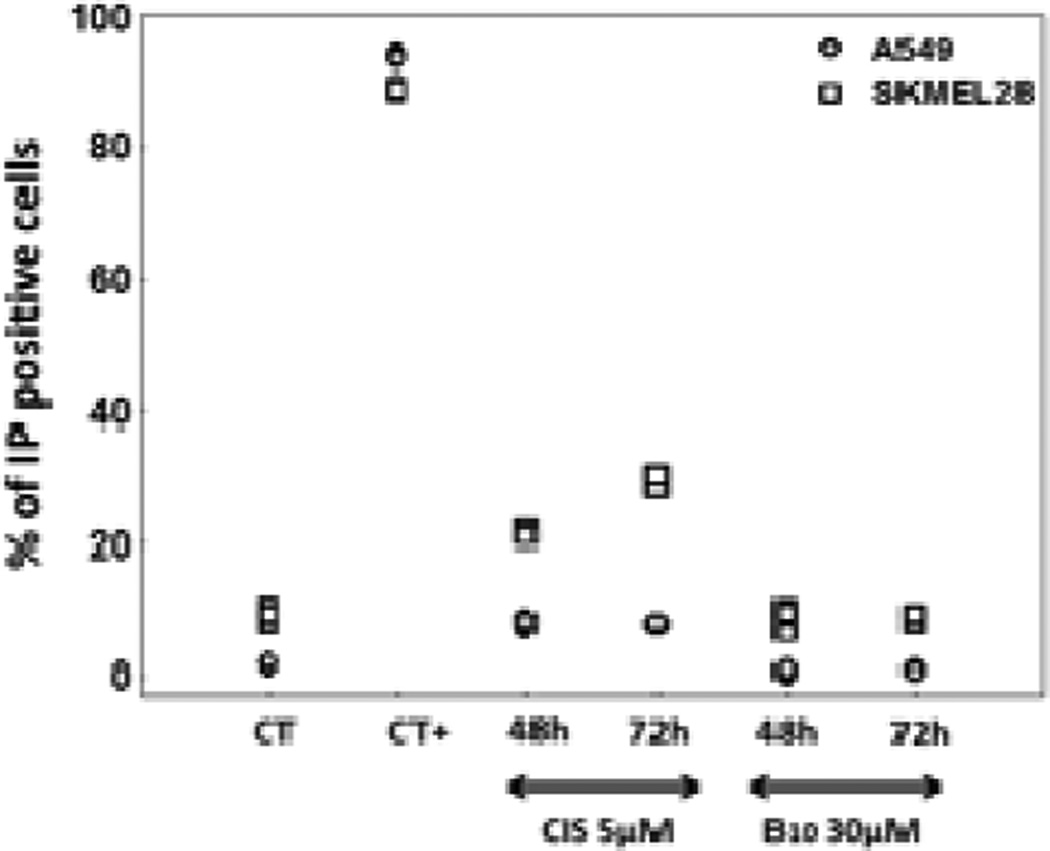

To confirm that indoles B do not induce cell death as suggested by the videomicroscopy experiments, we employed flow cytometric propidium iodide staining, which detects necrotic and late apoptotic cells that have lost the plasma membrane integrity (Figure 2). The experiments performed with apoptosis resistant A549 NSCLC and SKMEL-28 cells indicate that B10 at its GI50 concentration of 30 μM does not induce any cell permeabilization even after 72 h of treatment in both cell types. In contrast, 90% of ice-cold ethanol fixed and permeabilized cells were positively stained and cisplatin, a pro-apoptotic agent, induced an increase in the percentage of PI positive cells even in these apoptosis-resistant models (increase from 1 to 10% for A549 NSCLC and from 8 to 30% for SKMEL-28 cells).

Figure 2.

Percentage of cells that lost plasma membrane integrity after treatment with B10 as assessed by propidium iodide staining. Positive controls correspond to fixed and permeabilized corresponding cells.

In conclusion, the anticancer evaluation of C-3 derivatized 2-aryl indoles, accessible by a straightforward synthetic preparation utilizing the Fisher indole reaction, revealed their promising activity against apoptosis-resistant cancers associated with dismal clinical outcomes. The most promising structural type appears to be the C-3 ether and thioether indoles, which exhibit their antiproliferative effects mainly through cytostatic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103451) and National Cancer Institute (CA-135579) as well as Texas State University startup funding to AK. The authors thank Thierry Gras for his excellent technical assistance in cell culture. RK is a director of research and LMYB is a research assistant with the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS, Belgium).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Brenner H. The Lancet. 2002;360:1131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleihues P, Cavenee WK. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Nervous System, International Agency for the Research on Cancer (IARC) and WHO Health Organization. Oxford, UK: Oxford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefranc F, Sadeghi N, Camby I, Metens T, De Witte O, Kiss R. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:719. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.5.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giese A, Bjerkvig R, Berens ME, Westphal M. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:1624. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson CD, Anyiwe K, Schimmer AD. Cancer Lett. 2008;272:177. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savage P, Stebbing J, Bower M, Crook T. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2009;6:43. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson TR, Johnston PG, Longley DB. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2009;9:307. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamoral-Theys D, Pottier L, Dufrasne F, Nève J, Dubois J, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Ingrassia L. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010;17:812. doi: 10.2174/092986710790712183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Goietsenoven G, Andolfi A, Lallemand B, Cimmino A, Lamoral-Theys D, Gras T, Abou-Donia A, Dubois J, Lefranc F, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1223. doi: 10.1021/np9008255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamoral-Theys D, Andolfi A, Van Goietsenoven G, Cimmino A, Le Calvé B, Wauthoz N, Mégalizzi V, Gras T, Bruyère C, Dubois J, Mathieu V, Kornienko A, Kiss R, Evidente A. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6244. doi: 10.1021/jm901031h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evdokimov N, Lamoral-Theys D, Mathieu V, Andolfi A, Pelly S, van Otterlo W, Magedov I, Kiss R, Evidente A, Kornienko A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:7252. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luchetti G, Johnston R, Mathieu V, Lefranc F, Hayden K, Andolfi A, Lamoral-Theys D, Reisenauer MR, Champion C, Pelly SC, van Otterlo WAL, Magedov IV, Kiss R, Evidente A, Rogelj S, Kornienko A. ChemMedChem. 2012;7:815. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seth D, Hayden K, Malik I, Porch N, Tang H, Rogelj S, Frolova LV, Lepthien K, Kornienko A, Magedov IV. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4720. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przheval’skii NM, Skvortsova NS, Magedov IV. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2002;38:1055. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Przheval’skii NM, Magedov IV, Drozd VN. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 1997;33:1475. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przheval’skii NM, Skvortsova NS, Magedov IV. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2003;39:161. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Przheval’skii NM, Skvortsova NS, Magedov IV. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2004;40:1435. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen T, Darro F, Petein M, Raviv G, Pasteels JL, Kiss R, Schulman CC. Cancer. 1996;77:144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960101)77:1<144::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branle F, Lefranc F, Camby I, Jeuken J, Geurts-Moespot A, Sprenger S, Sweep F, Kiss R. Cancer. 2002;95:641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieu A, Remmelink M, D’Haene N, Penant S, Gaussin JF, Van Ginckel R, Darro F, Kiss R, Salmon I. Cancer. 2004;101:1908. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathieu V, Pirker C, Martin de Lasalle E, Vernier M, Mijatovic T, De Neve N, Gaussin JF, Dehoux M, Lefranc F, Berger W, Kiss R. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:3960. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]