Abstract

Background

Although it is possible to recover the complete mitogenome directly from shotgun sequencing data, currently reported methods and pipelines are still relatively time consuming and costly. Using a sample of the Australian freshwater crayfish Engaeus lengana, we demonstrate that it is possible to achieve three-day turnaround time (four hours hands-on time) from tissue sample to NCBI-ready submission file through the integration of MiSeq sequencing platform, Nextera sample preparation protocol, MITObim assembly algorithm and MITOS annotation pipeline.

Results

The complete mitochondrial genome of the parastacid freshwater crayfish, Engaeus lengana, was recovered by modest shotgun sequencing (1.2 giga bases) using the Illumina MiSeq benchtop sequencing platform. Genome assembly using the MITObim mitogenome assembler recovered the mitochondrial genome as a single contig with a 97-fold mean coverage (min. = 17; max. = 138). The mitogenome consists of 15,934 base pairs and contains the typical 37 mitochondrial genes and a non-coding AT-rich region. The genome arrangement is similar to the only other published parastacid mitogenome from the Australian genus Cherax.

Conclusions

We infer that the gene order arrangement found in Cherax destructor is common to Australian crayfish and may be a derived feature of the southern hemisphere family Parastacidae. Further, we report to our knowledge, the simplest and fastest protocol for the recovery and assembly of complete mitochondrial genomes using the MiSeq benchtop sequencer.

Keywords: Freshwater crayfish, Mitochondrial genome characterization, Bench top sequencing, Engaeus, Parastacidae

Background

Sequencing of mitochondrial genomes has become an important endeavour for providing molecular resources for population genetic and phylogeographic studies [1-3]. With the rising number of sequenced mitogenomes there has also been increasing interest in using this information for phylogenetic studies [4-8]. Further, as more full mitochondrial genomes are sequenced, there are interesting patterns of mitochondrial gene order that demand explanation and are themselves an additional source of phylogenetic signal [7,8]. Until recent years, the recovery of whole mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) has been inefficient, with most approaches utilising either cloning or long range PCR (which may or may not be successful), followed by a series of Sanger sequencing [4,9-11]. More recently, however, the increasing power of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) has allowed the amplification-free sequencing of whole mtDNA genomes [12,13]. This latter approach has been demonstrated using modest shotgun sequencing on platforms such the Illumina HiSeq, Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (GA IIx) and Roche 454 [14-17]. In the case of Miller et al’s study, a mitogenome to 800 × coverage from 1/16th of a plate was recovered using 454. Further, Berman et al. also showed that modest NGS outputs designed to identify microsatellite loci can be also be used to recover whole mitochondrial genomes [18]. Although these platforms represent a significant improvement over the conventional Sanger sequencing, the sample preparation and sequencing protocols are still relatively time consuming and laborious. Additionally, for the HiSeq platform, the run time can take up to 10 days. Coupled with its overly massive data output (600 gb), the HiSeq platform is not practical for the sequencing of mitogenomes. Although the data output is lower (90 gb) for the GA IIx platform, the operation of this system can represent a major technical challenge due to the lack of automation as compared to the HiSeq thus increasing the chance of human error and run failure. The sequencing chemistry of Roche 454 has been acknowledged to be susceptible to homopolymer issues hence representing a potential threat to the accuracy of the mitogenome assembly. Further, its high running cost and low data output also rendered it less cost-friendly for mitogenome sequencing. The development of the MiSeq benchtop sequencer and the timely introduction of MITObim [14], a low computationally demanding software for the assembly of mitochondrial genomes using a novel baiting and iterative mapping approach, serves as an impetus for the growth in NGS-based mitogenome assemblies. Although a successful mitogenome assembly using the MiSeq benchtop sequencer has been demonstrated recently, the library preparation steps for sequencing on the MiSeq were not covered in sufficient details nor was MITObim implemented in the assembly pipeline [19]. Using a sample of the Australian freshwater crayfish Engaeus lengana[20], we contribute to the growing interest in mtDNA genome sequencing by providing a detailed protocol for the fastest recovery, assembly and annotation of mitogenome using the MiSeq personal genome sequencer, MITObim software and MITOS annotation web service.

Australia has a diverse and distinctive freshwater crayfish fauna despite the continent’s aridity. One of the most intriguing genera of Australian crayfishes are the land yabbies from the genus Engaeus, which can complete their life cycle without access to surface water [20,21]. While the understanding of the evolution of Engaeus and other crayfishes have benefited from access to molecular data, only one full mitogenome is available for the southern hemisphere crayfish from the genus Cherax[4]. Major mitogenome rearrangements were identified in the species Cherax destructor compared to what is considered the Pan-crustacean plan [22]. A recent study indicates that northern hemisphere crayfish also have profound mitochondrial gene order rearrangements [22,23], albeit different to the rearrangements identified in Cherax. Kim et al. in their study of the marine lobster, Homarus americanus, emphasised the need for the sequencing of more mitogenomes from the superfamily Astacidae [22].

The purpose of this study is two-fold: first to demonstrate the simplest protocol, to our knowledge, for the recovery of whole mitochondrial genomes directly from shotgun sequencing reads using the MiSeq platform. This protocol requires only 50 ng of DNA extracted from a single ethanol-preserved specimen, without the need for mtDNA enrichment; and, secondly, we use the Australian freshwater crayfish E. lengana to investigate further mitochondrial genome evolution in parastacid freshwater crayfishes, building on the work of Miller et al.[4] who sequenced the C. destructor mitogenome.

Results

Mitogenome assembly, coverage and composition

A total of 4,761,100 paired-end reads amounting to approximately 1.2 giga bases of raw sequence data were generated from an E. lengana library. The MITObim selective-assembly of the raw reads resulted in the recovery of the complete mitochondrial genome of E. lengana [GenBank:KF546209] consisting of 15,934 bp (AT content of 66.27%). We also undertook a de novo assembly followed by BLAST against a fragment of the 16S rRNA gene region, which led to the recovery of the same mitogenome sequences but at the cost of significantly greater computational resources. The mitogenome contains 13 protein coding, two ribosomal RNA and 22 tRNA genes (Table 1 and Figure 1). Based on Bowtie2 mapping, a total of 6,442 reads (0.1% of total reads) were mapped to the constructed mitogenome giving relatively evenly distributed read coverage. The major exception is the putative control region spanning from position 8,686 to 9,556, where the coverage range is from 17 to 50 (Figure 1). The overall AT content of the E. lengana α-strand and β-strand is 62.92% and 66.99% respectively. A total of 1,264 non-coding nucleotides were observed over multiple intergenic regions. The longest non-coding region (976 bp) was located between the tRNAmet and tRNAval genes. Given that the AT content in this non-coding region is significantly higher than the rest of the mitogenome (Chi-square test, P < 0.001), it most likely represents the control region and is located in a similar region to the control region identified in C. destructor.

Table 1.

The mitochondrial genome organization of E. lengana

| Gene | Start | End | Orientation | No. of nt (bp) | Intergenic sequence | Putative initiation/termination codon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox1 |

1 |

1566 |

Forward |

1566 |

−31 |

Undetermined/TAA |

| trnL2(taa) |

1535 |

1601 |

Forward |

67 |

2 |

|

| cox2 |

1603 |

2292 |

Forward |

690 |

8 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnK(ttt) |

2300 |

2364 |

Forward |

65 |

1 |

|

| trnD(gtc) |

2365 |

2427 |

Forward |

63 |

2 |

|

| atp8 |

2429 |

2587 |

Forward |

159 |

−12 |

ATG/TAA |

| atp6 |

2575 |

3255 |

Forward |

681 |

0 |

TTG/TAA |

| cox3 |

3255 |

4043 |

Forward |

789 |

−2 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnG(tcc) |

4041 |

4104 |

Forward |

64 |

−10 |

|

| nad3 |

4094 |

4459 |

Forward |

366 |

−2 |

ATA/TAG |

| trnA(tgc) |

4457 |

4518 |

Forward |

62 |

2 |

|

| trnR(tcg) |

4520 |

4579 |

Forward |

60 |

0 |

|

| trnN(gtt) |

4579 |

4642 |

Forward |

64 |

1 |

|

| trnS1(tct) |

4643 |

4708 |

Forward |

66 |

0 |

|

| trnE(ttc) |

4708 |

4771 |

Forward |

64 |

0 |

|

| trnF(gaa) |

4771 |

4832 |

Reverse |

62 |

1 |

|

| nad5 |

4833 |

6560 |

Reverse |

1728 |

0 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnH(gtg) |

6560 |

6625 |

Reverse |

66 |

8 |

|

| trnT(tgt) |

6633 |

6694 |

Forward |

62 |

13 |

|

| nad6 |

6707 |

7225 |

Forward |

519 |

0 |

ATC/TAA |

| trnP(tgg) |

7225 |

7291 |

Forward |

67 |

−25 |

|

| rrnL |

7266 |

8646 |

Reverse |

1381 |

−30 |

|

| trnV(tac) |

8616 |

8685 |

Reverse |

70 |

872 |

|

| trnM(cat) |

9557 |

9626 |

Forward |

70 |

2 |

|

| nad2 |

9628 |

10635 |

Forward |

1008 |

5 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnW(tca) |

10640 |

10709 |

Forward |

70 |

3 |

|

| trnY(gta) |

10712 |

10773 |

Reverse |

62 |

5 |

|

| nad4 |

10778 |

12088 |

Reverse |

1311 |

30 |

ATA/TAA |

| nad4l |

12118 |

12408 |

Reverse |

291 |

51 |

ATA/T* |

| cob |

12459 |

13610 |

Forward |

1152 |

−16 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnS2(tga) |

13594 |

13658 |

Forward |

65 |

23 |

|

| nad1 |

13681 |

14610 |

Reverse |

930 |

17 |

ATG/TAA |

| trnL1(tag) |

14627 |

14693 |

Reverse |

67 |

4 |

|

| rrnS |

14697 |

15522 |

Reverse |

826 |

176 |

|

| trnQ(ttg) |

15698 |

15767 |

Reverse |

70 |

37 |

|

| trnI(gat) |

15804 |

15868 |

Forward |

65 |

0 |

|

| trnC(gca) | 15868 | 15933 | Reverse | 66 | 1 |

Figure 1.

The complete mitogenome of E. lengana. BRIG visualization showing the mapping coverage, protein coding genes, rRNAs and tRNAs in the mitogenome of E. lengana. A lower mapping coverage can be observed at the putative control region. GC content is shown on the outer surface of the ring whereas AT content is shown on the inner surface.

Proteins and codons

The typical 13 mitochondrial protein coding genes (11,190 bp) were identified spanning 70.22% of the mitogenome. The predominant stop codon is TAA with the exception being for nad2 and nad4l, which use TAG and an incomplete termination codon respectively. Incomplete termination codons are fairly common in metazoan mitogenomes and can be converted into a potential stop codon via polyadenylation to TAA [24] (Table 1). In general, the composition of AT bases is higher in the 3rd codon (Chi-square test, p < 0.001). The composition of guanine base at the 3rd codon on the beta-strand is substantially higher than that from the alpha strand (21.42% vs 3.81%) and the reverse for the composition of the cytosine base (2.75% vs 25.80%) (Chi-square test, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Base composition of protein coding genes in the E. lengana mitogenome

| A | C | G | T | (A + T) | (G + C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All genes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1st codon |

27.59 |

18.53 |

22.47 |

31.42 |

59.01 |

41.00 |

| 2nd codon |

17.86 |

21.15 |

16.92 |

44.08 |

61.94 |

38.07 |

| 3rd codon |

32.9 |

17.02 |

10.51 |

39.57 |

72.47 |

27.53 |

| Total |

26.11 |

18.9 |

16.63 |

38.36 |

64.47 |

35.53 |

| Genes encoded on α-strand |

|

|

|

|

||

| 1st codon |

28.4 |

23.12 |

19.87 |

28.61 |

57.01 |

42.99 |

| 2nd codon |

18.61 |

24.59 |

14.07 |

42.73 |

61.34 |

38.66 |

| 3rd codon |

33.59 |

25.8 |

3.81 |

36.8 |

70.39 |

29.61 |

| Total |

26.87 |

24.5 |

12.58 |

36.05 |

62.92 |

37.08 |

| Genes encoded on β-strand |

|

|

|

|

||

| 1st codon |

26.27 |

11.06 |

26.69 |

35.99 |

62.26 |

37.75 |

| 2nd codon |

16.62 |

15.56 |

21.55 |

46.27 |

62.89 |

37.11 |

| 3rd codon |

31.76 |

2.75 |

21.41 |

44.08 |

75.84 |

24.16 |

| Total | 24.88 | 9.79 | 23.22 | 42.11 | 66.99 | 33.01 |

Gene order

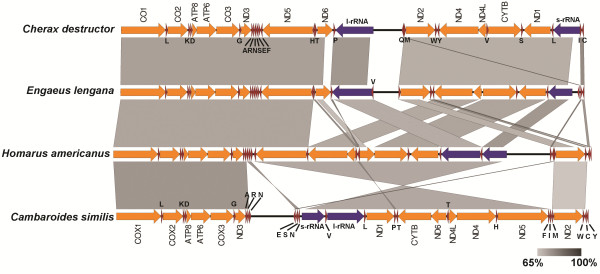

The gene organization in the E. lengana mitogenome is almost identical to that of C. destructor, the only other parastacid crayfish, for which a whole mitogenome is available with the exception being the positions of tRNAmet and tRNAval. In E. lengana, the tRNAmet is located upstream of nad2 while in C. destructor, it is located downstream of the ssuRNA. The tRNAval gene is located downstream of the lsuRNA of E. lengana but in C. destructor, it is located upstream of the cob gene (Figure 2). It should be noted that the position of tRNAval was only putatively identified by Miller et al.[4]. Notably, in both C. destructor and E. lengana, the ribosomal RNA genes are separated by nad2, nad4, nad4l, cob and nad1 genes, which is not observed in the mitogenome of other members of the infraorder Astacidea such as the American lobster, Homarus americanus or the northern hemisphere crayfish, Cambaroides similis and Procambarus clarkii[22,23].

Figure 2.

The gene organization in the E. lengana mitogenome and its high similarity to C. destructor. Linear genome comparison of the mitogenomes of E. lengana, C. destructor (Accession number: AY383557), C. similis (Accession number: JN991196) and Homarus americanus (Accession number: NC_015607) and. Regions of similarity based on BLASTn which satisfy the E-value threshold of less than 0.001 are shown.

Non-coding RNA

A total of 22 tRNA genes were predicted in the mitogenome of E. lengana with length ranging from 60 to 70 bp. Inferred cloverleaf secondary structures of tRNAs are presented in Figure 3. In one of the tRNAser structures, only a limited trace of the “DHU” arm is present. The large ribosomal rRNA (1,381 bp) is flanked by tRNApro and tRNAval while the small ribosomal (826 bp) is flanked by tRNAleu and tRNAmet.

Figure 3.

Predicted tRNA structures. 22 tRNAs are identified in the mitogenome of E. lengana and their cloverleaf secondary structures of tRNAs are inferred with Infernal software module, which is part of the MITOS annotation pipeline.

Discussion

The time taken from sample extraction to submission-ready full mitogenome sequence was only three days, and hands-on time was less than four hours. This makes our workflow one of the most efficient thus far reported [11,16,19,22,25]. The low-input DNA-quantity requirement and the simplicity of this protocol are particularly advantageous for new users as it minimizes the risk of failure and reduces sample quantity requirements. The MiSeq data output per run (4.5-7.5 gb) will enable sequencing of multiple samples via barcoding. Given that the data generated in this study (97-fold coverage) is more than twice that required to confidently deduce mitogenomes using MiSeq [18] , this means $100 mt genomes are now obtainable. According to the animal genome database (http://www.genomesize.com), the average genome size of a crayfish can range from 3.5 to 6 gb. Therefore, the percentage of reads mapping to the mitochondrial genome (0.1%) in E. lengana can be considered to be on the high side for enrichment-free shotgun sequencing. This may also reflect the use of muscle tissue, which has a high proportion of mitochondria. With additional pre-sequencing sample processing including mitochondrial enrichment [25], this would further reduce per-sample sequencing cost by allowing even more samples to be processed per run. Using this pipeline, we were also able to recover complete mitogenomes from very different organisms including the Australian Macquarie Perch, Macquaria australasica [EMBL:HG799088] and the Viet Nam Snout Otter Clam, Lutraria rhynchaena [EMBL:HG799089]. If further studies demonstrate wide utility of our methodology across a broad range of animal taxa, there exists the possibility of up-scaling DNA barcoding [26] from a small fragment of the mitochondrial COI gene to the level of the entire mitogenome.

For situations where there is no close relative to provide a “bait” sequence for MITObim, we demonstrated that a de novo assembly followed by BLAST search against the conserved mitochondrial genes (such as 16S rRNA) was effective for identifying mitogenome fragment(s) from the generated sequences. These can then in turn be used as the bait for a MITObim assembly.

This study brings the number of freshwater crayfish mitogenomes to five, comprising three from the northern hemisphere superfamily the Astacoidea (Procambarus and Cambaroides) [23] and now two from the southern hemisphere superfamily Parastacidae (Engaeus and Cherax) [4]. The representatives of each superfamily have substantial gene order rearrangements in comparison to each other and their nearest relative from the marine clawed lobsters, Homarus americanus (Superfamily: Nephropoidea). The latter has what is deemed to be the more primitive pan-crustacean gene order [22]. It is now apparent that Australian, and perhaps parastacid crayfish more generally, have one of the most elaborate gene order rearrangements so far discovered in the Arthropoda. It is possible that the translocation and inversion of the RNA genes is a distinctive feature of Australian crayfish. Future studies of freshwater crayfishes will likely benefit from the phylogenetic signal provided in mitochondrial gene order rearrangements [11,27,28].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that benchtop sequencers can be used to obtain fast and relatively inexpensive generation of mt DNA sequences using shotgun sequencing without mitochondrial enrichment. We also show that MITObim [14] is effective at recovering mitogenomes from raw benchtop sequencer output. Previously reported significant gene order rearrangements in Australian crayfish are confirmed. The further sequencing of mitogenomes of southern hemisphere crayfish (Parastacidae) and additional representatives of the northern hemisphere families (Cambaridae and Astacidae) will undoubtedly contribute to our phylogenetic knowledge of this significant group of crustaceans. Lastly, we predict that improvements to our workflow and increased output from benchtop sequencers will further reduce the cost of reconstructing mitogenomes to much less than $100 per mitogenome.

Methods

Genomics DNA extraction

Approximately 40 mg of tail muscle tissue was dissected from an ethanol-preserved specimen of E. lengana collected from northern Tasmania (−41.00877 ° S, 144.66869 ° E). Total genomic DNA was extracted using DNAeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modification. EB rather than AE buffer was used to avoid possible interference of EDTA with the Nextera enzyme.

Molecular procedures and sequencing

The purified genomic DNA was quantified with Qubit HS (Invitrogen, USA) and normalized to 2 ng/μL. The normalized DNA was processed using Nextera-based library preparation (Illumina, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification and size estimation of the library was performed on a Bioanalyzer 2100 High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent, USA). Next, the library was normalized to 2 nM and sequenced on the MiSeq Benchtop Sequencer (2 × 250 bp paired-end reads) (Illumina, USA).

Mitogenome assembly and annotation

The mitochondrial genome was reconstructed with MITObim [14] using the COI gene sequences of Engaeus sericatus (GenBank Accession number: FJ965960) as the seed reference and using the parameters: “--trim”, “–pair” and “--noshow”. As an alternative approach to using a seed reference we completed a de novo assembly using CLC Bio (CLC Genomics Workbench 5, Denmark) and searched for matches to the conserved 16S rRNA gene. The assembled mitogenome was then manually inspected for repeats at the beginning and end of the assembly to infer circularity. The mitogenome was annotated with MITOS [29] followed by manual validation of the coding regions using the NCBI ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gorf/). Based on ORF Finder result, the sqn file generated from MITOS was edited and submitted to NCBI. The steps involved, hands-on time and total time required from tissue sample to annotated mitogenome ready for NCBI submission is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Mitogenome recovery workflow. Steps involved, hands-on and total time required from raw tissue sample to annotated mitogenome.

Mitogenome visualization and linear comparison

The circular mitogenome of E. lengana was visualized with Blast Ring Image Generator (BRIG) [30]. Mapping statistic was generated by mapping the raw reads against the assembled mitogenome using Bowtie2 [31]. SAM file output from Bowtie2 was subsequently used to visualize the mapping coverage via BRIG [30]. Linear mitogenome comparison of E. lengana, C. destructor, Cambroides similes and H. americanus (Figure 2), was performed using EasyFig2.1 (BLASTn, default setting) [32].

Competing interests

H.M.G is an ex-employee of ScienceVision Sdn Bhd. ScienceVision Sdn Bhd is the sole distributor of Illumina products in Malaysia. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HMG and CMA conceived and designed the experiments. HMG performed the sequencing and analyzed the data. MBS and CMA contributed reagents, materials and analysis tools. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Han Ming Gan, Email: gan.han.ming@monash.edu.

Mark B Schultz, Email: mark.schultz@unimelb.edu.au.

Christopher M Austin, Email: chris.austin@monash.edu.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by the Monash University Malaysia (MUM) Tropical Medicine and Biology Multidisciplinary Platform and the work was conducted in the MUM Genomics Facility. We are especially grateful for the advice and assistance of Dr Christoph Hanh in the use of the MITObim software.

References

- Avise JC. Phylogeography: The History and Formation of Species. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Mable BK, Larson A, Davis SK, Zimmer EA. Molecular Systematics. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Santini F, Sorenson L, Alfaro ME. A new multi-locus timescale reveals the evolutionary basis of diversity patterns in triggerfishes and filefishes (Balistidae, Monacanthidae; Tetraodontiformes) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;69(1):165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Nguyen TT, Burridge CP, Austin CM. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the Australian freshwater crayfish, Cherax destructor (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae): a novel gene order revealed. Gene. 2004;331:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masta SE, Longhorn SJ, Boore JL. Arachnid relationships based on mitochondrial genomes: asymmetric nucleotide and amino acid bias affects phylogenetic analyses. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;50(1):117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cui Z. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Chinese spiny lobster Panulirus stimpsoni (Crustacea: Decapoda): genome characterization and phylogenetic considerations. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(1):403–410. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perseke M, Golombek A, Schlegel M, Struck TH. The impact of mitochondrial genome analyses on the understanding of deuterostome phylogeny. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;66(3):898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon S, Hadrys H. A comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes among Hexapoda. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;15(13):00153–00155. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SL, Sullivan J, Song H, Miller KB, Whiting MF. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of the Neuropterida (lace-wings, alderflies and snakeflies) and their relationship to the other holometabolous insect orders. Zool Scr. 2009;38(6):575–590. [Google Scholar]

- Prosdocimi F, de Carvalho DC, de Almeida RN, Beheregaray LB. The complete mitochondrial genome of two recently derived species of the fish genus Nannoperca (Perciformes, Percichthyidae) Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(3):2767–2772. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen J, Byrkjedal I, Willassen E, Rees D, Takeshima H, Satoh T, Shinohara G, Nishida M, Miya M. Mitogenomic sequences and evidence from unique gene rearrangements corroborate evolutionary relationships of myctophiformes (Neoteleostei) BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13(1):111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Liu Y, Li CP, You F, Chu KH. The complete mitochondrial genome of the large yellow croaker, Larimichthys crocea (Perciformes, Sciaenidae): unusual features of its control region and the phylogenetic position of the Sciaenidae. Gene. 2009;432(1–2):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jex AR, Hall RS, Littlewood DT, Gasser RB. An integrated pipeline for next-generation sequencing and annotation of mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(2):522–533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C, Bachmann L, Chevreux B. Reconstructing mitochondrial genomes directly from genomic next-generation sequencing reads–a baiting and iterative mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(13):9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorizzo M, Senalik D, Szklarczyk M, Grzebelus D, Spooner D, Simon P. De novo assembly of the carrot mitochondrial genome using next generation sequencing of whole genomic DNA provides first evidence of DNA transfer into an angiosperm plastid genome. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12(61):1471–2229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Good RT, Coleman RA, Lancaster ML, Weeks AR. Microsatellite loci and the complete mitochondrial DNA sequence characterized through next generation sequencing and de novo genome assembly for the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot, Neophema chrysogaster. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1950-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenenberg DSJ, Pirovano W, Gittenberger E, Schilthuizen M. The complete mitogenome of Cylindrus obtusus (Helicidae, Ariantinae) using Illumina next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman M, Miller AD, Austin CM. Characterisation of the complete mitochondrial genome and 13 microsatellite loci through next-generation sequencing for the New Caledonian spider-ant Leptomyrmex pallens. Mol Biol Rep. 2013. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Williams ST, Foster PG, Littlewood DTJ. The complete mitochondrial genome of a turbinid vetigastropod from MiSeq Illumina sequencing of genomic DNA and steps towards a resolved gastropod phylogeny. Gene. 2014;533:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz P, Richardson AM. An ecological classification of the burrows of Australian freshwater crayfish. Aust J Mar Freshwat Res. 1986;37:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz MB, Smith SA, Horwitz P, Richardson AM, Crandall KA, Austin CM. Evolution underground: a molecular phylogenetic investigation of Australian burrowing freshwater crayfish (Decapoda: Parastacidae) with particular focus on Engaeus Erichson. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;50(3):580–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee SH, Park MH, Choi HG, Park JK, Min GS. The complete mitochondrial genome of the American lobster, Homarus americanus (Crustacea, Decapoda) Mitochondrial DNA. 2011;22(3):47–49. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2011.597389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Park M-H, Jung J-H, Ahn D-H, Sultana T, Kim S, Park J-K, Choi H-G, Min G-S. The mitochondrial genomes of Cambaroides similis and Procambarus clarkii (Decapoda: Astacidea: Cambaridae): the phylogenetic implications for Reptantia. Zool Scr. 2012;41(3):281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala D, Montoya J, Attardi G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature. 1981;290(5806):470–474. doi: 10.1038/290470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatharia S, Joshi M, Pandya R, Pandit A, Patel R, Desai S, Sharma A, Panchal O, Jasmani F, Saxena A. Complete mitogenome of asiatic lion resolves phylogenetic status within Panthera. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):572. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PDN, Stoekle MY, Zemlak TS, Francis CM. Identification of birds through DNA barcodes. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpert F, Held C, Podsiadlowski L. Multiple rearrangements in mitochondrial genomes of Isopoda and phylogenetic implications. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;64(1):106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima Y, Kumazawa Y. Mitochondrial genomes of acrodont lizards: timing of gene rearrangements and phylogenetic and biogeographic implications. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10(1):141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernt M, Donath A, Juhling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, Putz J, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;7(12):00332–00336. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(402):1471–2164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(7):1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]