Abstract

Objective

To determine the pathogenesis of anti-muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) myasthenia, a newly described severe form of myasthenia gravis associated with MuSK antibodies, characterized by focal muscle weakness and wasting, and absence of acetylcholine receptor antibodies; also to determine whether antibodies to MuSK, a crucial protein in the formation of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) during development, can induce disease in the mature NMJ.

Design/Methods

Lewis rats were immunized with a single injection of a newly discovered splicing variant of MuSK, MuSK 60, which has been demonstrated to be expressed primarily in the mature NMJ. Animals were assessed clinically, serologically and by repetitive stimulation of median nerve. Muscle tissue was examined immunohistochemically and by electron microscopy.

Results

Animals immunized with 100ug of MuSK 60 develop severe progressive weakness, starting at day 16, with 100% mortality by day 27. The weakness is associated with high MuSK antibody titers, weight loss, axial muscle wasting and decrementing compound muscle action potentials. Light and electron microscopy demonstrate fragmented NMJs with varying degrees of postsynaptic muscle endplate destruction along with abnormal nerve terminals, lack of registration between endplates and nerve terminals, local axon sprouting and extrajunctional dispersion of cholinesterase activity.

Conclusions

These findings: 1) support the role of MuSK antibodies in the human disease; 2) demonstrate the role of MuSK, not only in the development of the NMJ, but also in the maintenance of the mature synapse; and 3) demonstrate involvement in this disease of both pre- and post-synaptic components of the NMJ.

Introduction

Ninety percent of patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (MG) have pathogenic antibodies (Abs) to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR), the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor. However, in about five percent of cases, AChR Abs are absent but, rather, these patients have circulating Abs to a second postsynaptic NMJ protein, muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) 1. The latter subgroup of patients, which we will refer to as anti-MuSK myasthenia (AMM), has many clinical similarities to AChR-Ab-positive MG, but tends to differ significantly in demonstrating more focal involvement, with severe weakness of neck, shoulder, facial and bulbar muscles, frequently with wasting of these muscles 2–5. In contrast to AChR-Ab-positive MG, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying AMM are little understood. In fact there has been debate over whether MuSK antibodies play a direct role in AMM, or whether, alternatively, they represent an epiphenomenon 6,7. The current study is aimed at addressing this question and better defining the mechanisms by which such an immune attack may produce the disease.

MuSK plays a crucial role in the development of the NMJ. The synapse begins to form when the axon growth cone of a developing motor neuron encounters a developing myotube and begins to secrete the glycoprotein agrin 8–10. Agrin binds to the complex of MuSK and a second transmembrane muscle protein, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (lrp4) 11–14, leading to dense clustering of the AChRs in the postsynaptic endplate membrane, which is the first step in the formation of the mature NMJ structure, including the pretzel-like topographic profile of the endplate membrane and its folding and specialization at the ultrastructural level 8–10,15. In contrast, the role of MuSK in the mature NMJ has been less well delineated 16,17, raising the question of the mechanisms by which Ab attack on this molecule in the adult NMJ alters its function 6,3,7,18.

MuSK is a 100kD transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase with an N-terminal extracellular domain followed by a short transmembrane domain and then a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain 19–21. The extracellular domain, which appears to be required for interaction with agrin and lrp4, comprises three immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains followed by a cysteine-rich (frizzled-like) domain 13,14,20–23. It is only the extracellular domain of the molecule that is the target of the AMM Abs 1. We have recently identified a splicing variant of MuSK, MuSK 60, containing an additional twenty-residue domain located between Ig-2 and Ig-3 expressed primarily in adult muscle 24, which appears from the present study to be an important antigen in AMM 25.

We report here the production of a very severe acute model of AMM, experimental AMM (EAMM), which reproduces all the major characteristics of the human disease: fatigable weakness, disordered neuromuscular transmission and wasting of axial musculature. Immunization with a single injection of 100 ug of the extracellular domain of the MuSK 60 isoform 24 induces very high anti-MuSK antibody titers (>1:106) and severe weakness that is lethal by day 27 after immunization. Immunization with lower doses of this antigen produces a more chronic disease with lower anti-MuSK titers. Analysis of NMJ morphology in these animals suggests that antibody attack on MuSK affects both postsynaptic and presynaptic components of this synapse.

Materials and Methods (Details in Supplemental Material)

Production, Detection and Purification of N-MuSK 60 Protein

MuSK cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR using total RNA from mouse adult (innervated) muscle (Invitrogen Corp.). DNA sequence analysis of these clones identified a variety of isoforms of mouse MuSK including the one published sequence in Gene Bank. Among the other isoforms, we identified a novel MuSK splicing variant (which we have referred as MuSK 60), containing an additional 60 nucleotides in frame in the region between Ig-2 and Ig-3 and expressed primarily in adult muscle24. The N-terminal extracellular domain of MuSK 60 (N-MuSK 60) was obtained from the culture supernatants of COS7 and CHO cells transiently transfected with the expression and secretion vector, pSecTag2/Hygro containing the tagged (3′ myc-epitope and polyhistidine) N-MuSK 60 cDNA. The secreted protein was purified using an affinity column loaded with Profinity IMAC Ni-charged resin (Bio-Rad).

Animals and Immunizations

0.25 ml of purified N-MuSK 60, the “adult isoform,” either 50 ug or 100 ug, or buffer, was emulsified with an equal volume of complete Freund’s adjuvant. The emulsion was injected into three separate intradermal sites into female Lewis rats, 175–200g, along with 2.5 ug of pertussis vaccine injected at a single separate subcutaneous site

Antibody Titration

Sera were diluted with tris buffered saline containing 4% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% tween 20 and subjected to immuno-dot blot against 0.5 ug of affinity-purified N-MuSK 60 or 0.5 ug of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (control) blotted on nitrocellulose membranes.

Electrophysiologic Studies

Repetitive stimulations (3 Hz) of median nerve, recording compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) from the flexor digitorum muscle, were performed on anesthetized animals 26. Tracings were recorded using digital photography of the oscilloscope screen and the decrement of the 5th response, compared to the 1st response calculated.

Tissue Processing

Muscle tissue, diaphragm, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior, was obtained at euthanasia, either before or following cardiac perfusion with 4 per cent paraformaldehyde, and prepared for immunohistochemistry, histochemistry and electron microscopy as we have previously described 27,28. Frozen sections of diaphragm were labeled with Alexa-594 conjugated alpha-bungarotoxin and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to synapsin and neurofilament. Morphometric analyses of the electron micrographs, as we have previously described, employed ImageJ software 29–31.

Statistical Analyses

All assessments involved continuous variables analyzed by t test.

Results

Production and Purification of N-MuSK 60

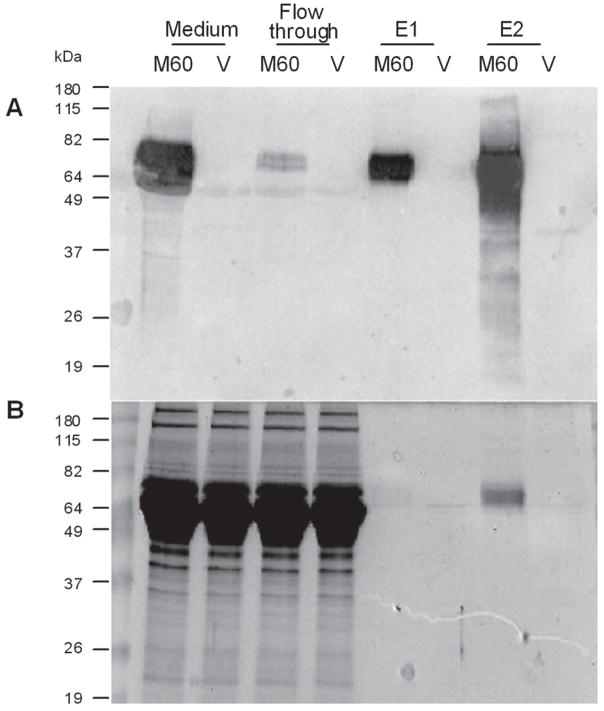

For this study, we employed the variant, MuSK 60, that we have recently identified 24, which is expressed in high proportion in adult muscle. We purified on the order of 2 ug of N-MuSK 60 per ml of culture medium of COS7 cells transiently transfected with cDNA encoding this domain (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. N-MuSK 60 Purification.

The culture media from COS7 cells transfected with N-MuSK 60 vector (M60) or empty vector (V) was applied to a Ni column and eluted with buffer containing imidazole. A. Western blot demonstrating a strong immuno-reacting band in original culture medium and first (E1) and second (E2) effluent fractions. B. Coomassie stained SDS-gel electrophoresis. The immuno-reacting band in the second elution fraction corresponds to a single Coomassie-stained band.

Induction of EAMM in Lewis rats

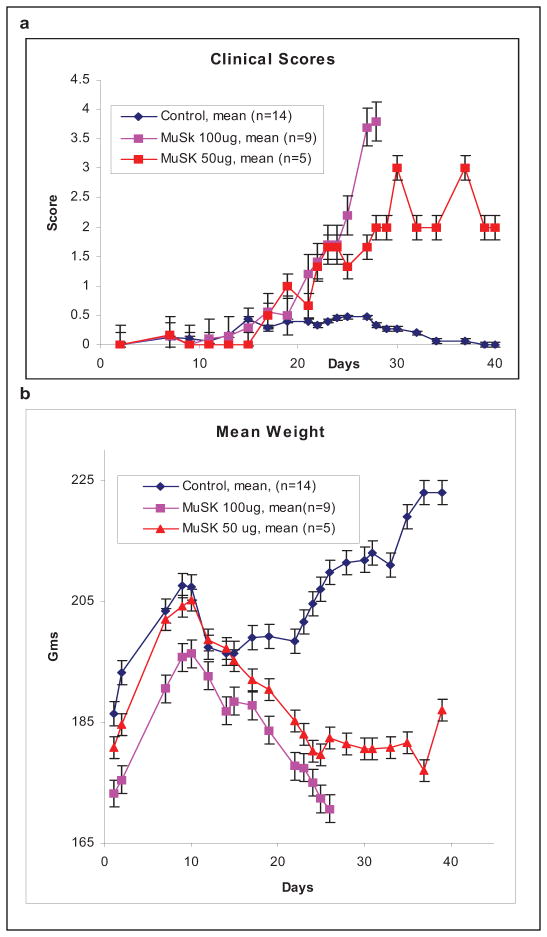

Fourteen 175–200g female Lewis rats were immunized with a single injection of purified mouse N-MuSK 60 in complete Freund’s adjuvant and 14 were immunized with adjuvants alone. Of the N-MuSK 60-immunized animals, 9 received 100ug of antigen and 5 received 50ug. Beginning at day 16 after injection, the MuSK-immunized animals developed fatigable weakness and accelerating weight loss (Figs. 2A and 2B). The 9 animals immunized with 100ug N-MuSK 60 were all moribund by day 27 and the 5 animals immunized with 50ug had less severe disease, with only one mortality (day 40). Aside from mild transient adjuvant arthritis in 6 animals, the adjuvant controls remained normal for more than 12 weeks.

Figure 2. Clinical Course.

a. Rats immunized with 100ug N-MuSK 60 developed more severe weakness than those immunized with 50ug. The clinical scores: 0=normal; 1=weak grip; 2=abnormal gait; 3= walking only a few steps at a time with waddle and kyphosis; 4= inability to stand; 5= moribund. b. Mean weight of these animals demonstrating more severe weight loss in rats immunized with100ug N-MuSK 60. Error bars=SEM.

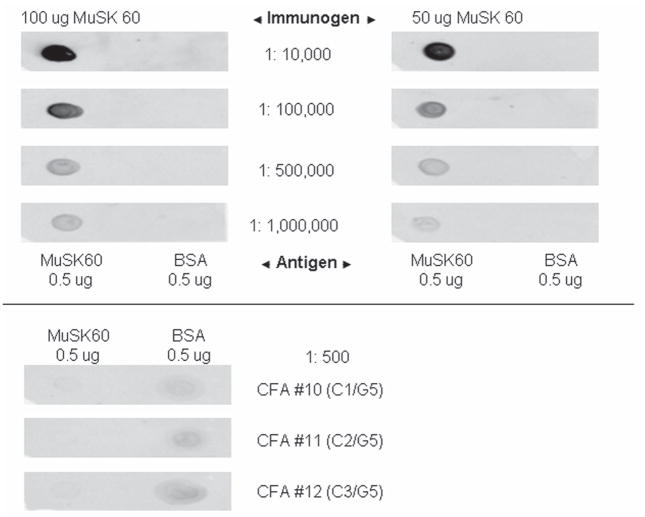

All animals immunized with 100 ug of MuSK had serum MuSK 60 antibody titers of >1: 106, whereas the 5 immunized with 50 ug of MuSK had lower titers, 1:105, and the 14 adjuvant controls and 4 untreated litter mates had undetectable titers (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Immuno-Dot Blot of Day 27 Sera.

Sera diluted from 1:104 through 1:106 from rat immunized with 100ug N-MuSK 60 (titer >1:106) and one immunized with 50ug (titer=1:105) blotted against 0.5ug affinity purified mouse N-MuSK 60 or 0.5ug BSA as an antigen control. Serum from three adjuvant control animals diluted 1:500 (lower panel) showed no reaction.

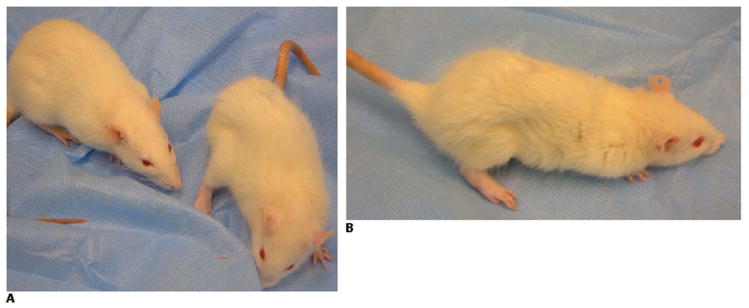

The weakness in the MuSK-immunized animals, which began in the forelimbs, progressed rapidly to axial muscles and hind limbs. As the disease progressed, the weight loss became pronounced and the animals developed progressive axial muscle wasting, along with waddling gait, marked kyphosis and ruffled, ungroomed fur (Fig. 4). The ability of these animals to eat, drink and chew was not observably abnormal until the last two days of life. At that time, water-soaked food pellets were placed in the floor of their cages and of the control animals. In spite of this maneuver, all animals immunized with 100 ug of MuSK were moribund by day 27.

Figure 4. Clinical Findings.

A: Rat immunized with 100 ug of N-MuSK 60 (right), day 25, with significant weight loss, flank and neck muscle wasting, extremity weakness, kyphotic posture and ruffled, ungroomed fur. Adjuvant control (left) is normal. B: Lateral view of N-MuSK 60-immunized rat from A.

Neuromuscular Transmission

The CMAP response to 3 Hz stimulation assessed in the flexor digitorum muscle on day 27 in the animals immunized with 100 ug N-MuSK 60 revealed mild decrement, mean 9.3%, whereas the animals immunized with 50 ug, studied at a later time, day 33–36, demonstrated more severe decrement, mean 15.6%, even though they were less weak than the 100 ug animals were at the time they were tested (Table 1 and Supplemental Material Fig. e1). No abnormalities to repetitive stimulation were observed in the 14 adjuvant controls on either day 27 or days 33–66. These observations suggest that the time course of the axial muscle wasting/weakness in EAMM and of that of the abnormal neuromuscular transmission, measured distally, may differ.

Table 1.

CMAP Responses to 3Hz Repetitive Median Nerve Stimulation (Mean ± SEM)

| Immunization (n) | Amplitude of First Response (mV) | Amplitude of Fifth Response (mV) | Decrement (%) | Decrement P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant Control (14) | 68.6±5.7 | 69.1±5.5 | −0.9±0.4 | -- |

| MuSK 100ug (9) | 64.0±3.5 | 57.9±3.4 | 9.3±1.7 | <0.0001 vs control |

| MuSK 50ug (5) | 65.0±5.2 | 54.6±4.0 | 15.6±2.3 | <0.005 vs control <0.05 vs MuSK 100ug |

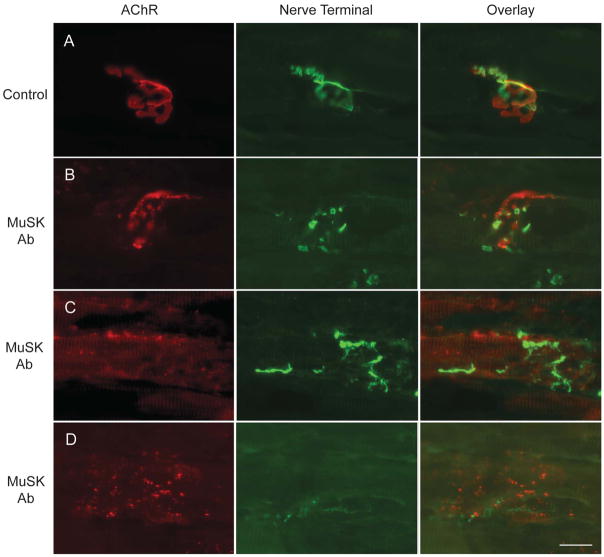

Neuromuscular Junction Morphology

Stained longitudinal frozen sections of diaphragm muscle from adjuvant-control animals were normal with the characteristic pretzel-shaped appearance of the endplate membrane and with the presynaptic terminal precisely apposed to the postsynaptic AChR-stained endplates (Fig. 5A). For the rats immunized with 100 ug of N-MuSK 60, the architecture and distribution of the postsynaptic components, as well as the presynaptic components, of the NMJs were highly abnormal. Most NMJs were disrupted, with the terminal arbors and AChR clusters being fragmented into smaller, discontinuous structures (Fig. 5B). This discontinuity was accompanied by decreased alignment of the pre- and postsynaptic elements. Many nerve terminals appeared to be degenerating and only occupied small portions of the postsynaptic receptor clusters. In other cases elongated globular nerve sprouts were observed extending for short distances away from the existing NMJ (Fig. 5C). In the most severe cases, only remnants of neuromuscular synapses remained; these consisted of widely dispersed, small AChR aggregates and no detectable nerve terminal (Fig. 5D). No inflammatory cells are identified at any NMJs (Supplemental Material Fig. e2). Thus, within individual muscles there were variable degrees of disruption from NMJ to NMJ. In addition, while similar changes were observed in a distal extremity muscle, tibialis anterior, fewer endplates were involved and the severity of the changes was less.

Figure 5. Frozen Sections of Diaphragm Muscle from MuSK-Immunized and Control Animals.

Adjuvant-controls (A) and MuSK-immunized (100 ug mouse N-MuSK 60) (B-D) rats were stained at day 27, with alpha-bungarotoxin to label AChR (red) and anti-synapsin plus anti-neurofilament antibodies to label presynaptic nerve terminals and axons (green). Scale bar = 20 um.

To quantify the changes (Table 2) in morphology, we analyzed these images of “en face” NMJs using Axiovision software. Compared to control, postsynaptic AChR staining segments in MuSK-immunized animals were composed of many more discontinuous regions (35.6 cf. 6.5), with each region being smaller in area (8.6 um2 cf. 44.1 um2). The maximal diameter of NMJs was also increased in MuSK-immunized animals compared to control (56 cf. 34 um). These results indicate a dramatic fragmentation of postsynaptic AChR segments in the MuSK-immunized animals, accompanied by a dispersal of the post-junctional fragments.

Table 2.

Morphometric Analysis of Neuromuscular Junctions (Mean ± SEM)

| Immunization | Number of regions per NMJ (n) | Area of individual regions (micron2) (n) | Maximal diameter of NMJ (micron) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant Control | 6.5±0.4 (78) | 44.1±3.6 (78) | 34.2±0.8 (70) |

| MuSK | 35.6±3.5 (65) P<0.01 |

8.6±1.0 (65) P<0.005 |

56.2±3.6 (87) P<0.02 |

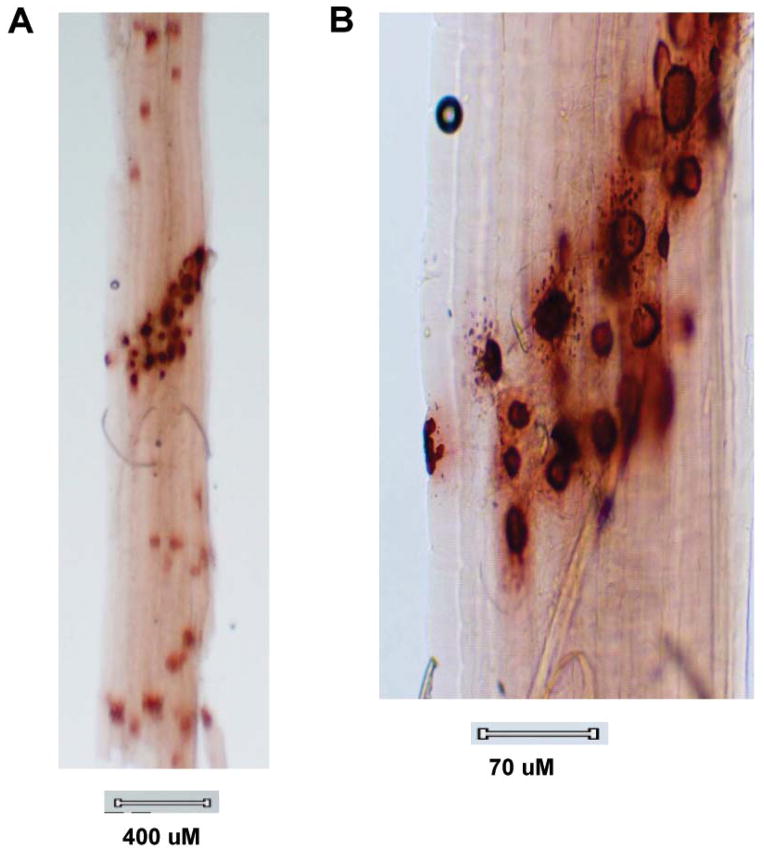

We also assessed cholinesterase-stained endplates in teased gastrocnemius muscle bundles (to identify synaptic regions for electron microscopic study), unexpectedly revealing variable degrees of patchy granular cholinesterase activity in extrajunctional regions of all myofibers (Fig. 6A), many quite distant from the innervation band, a finding not seen in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG) or our controls. Some of these “extrajunctional” stained structures have the size and appearance of endplates. At higher power of endplate regions (Fig. 6B), punctate cholinesterase staining was observed perijunctionally.

Figure 6. Cholinesterase-Stained Muscle Bundle.

Teased gastrocnemius muscle bundle from rat immunized with 100ug of N-MuSK 60, 27 days earlier, stained for cholinesterase activity demonstrating patchy staining beyond the endplate region along the entire muscle fiber (A) and, at higher power (B), punctate staining within and adjacent to endplate regions.

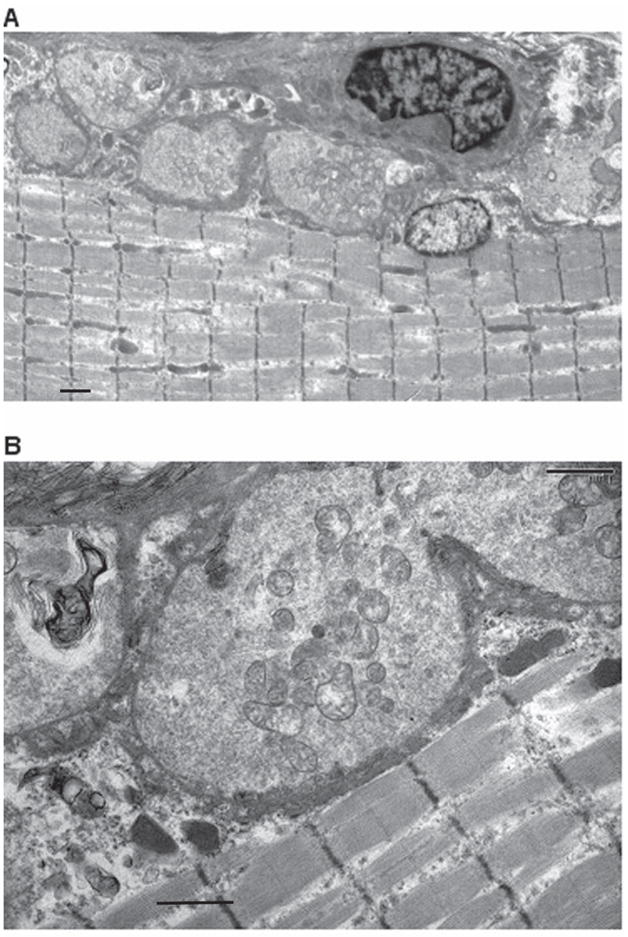

Neuromuscular junctions of gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 7A and 7B) from two of the animals immunized with 100 ug of N-MuSK 60 and two of the adjuvant control animals were examined with the electron microscope. The NMJs from the MuSK-immunized animals demonstrated (Table 3) hypersegmentation of some junctions (as manifested by increased numbers of junctional segments per unit of fiber length, 0.25/um compared to 0.15/um), and increased total nerve terminal area, 7.74 um2 compared with 0.064 um2. In addition there was marked simplification of post-synaptic membranes, resulting in reduced endplate index (EI = ratio of length of postsynaptic membrane to length of apposed pre-synaptic membrane) 27, 1.67 compared with 5.80, and reduced numbers of secondary endplate folds per length (um) of the primary cleft 27,30, 0.37 compared to 2.08. In none of these electron micrographs were were inflammatory cells observed.

Figure 7. Electron Micrographs of N-MuSK 60-Immunized Animals.

Electron micrographs of NMJs from gastrocnemius muscle of immunized rat (same muscle bundle as in Figure 6) demonstrating hypersegmented NMJs (A). At higher power (B), the post synaptic membranes of these NMJs are markedly simplified with sparse synaptic folds. (See Table 3) Scale bars = 1 um for A and 1 um for B.

Table 3.

Ultrastructural Analysis of Neuromuscular Junctions (Mean ± SEM)

| Immunization | Junctional segments per muscle fiber length (um) (n) | Endplate Index* (n) | Secondary clefts per primary cleft length (um) (n) | Nerve Terminal Area (um2) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant Control | 0.15±0.013 (18) | 5.80±0.49 (23) | 2.08±0.18 (23) | 0.064±0.011 (23) |

| MuSK | 0.25±0.002 (15) P<0.0001 |

1.67±0.11 (43) P<0.0001 |

0.37±0.001 (43) P<0.0001 |

7.74±0.52 (43) P<0.0001 |

Length of post-synaptic membrane/length of apposed pre-synaptic membrane

Together, these morphologic observations described above demonstrate that anti-MuSK attack produces severe disruption of both components of the NMJ and even complete loss of these structures.

Discussion

Experimental studies have supported the hypothesis that AMM is the result of the autoimmune response directed against MuSK, by observing weakness and NMJ changes in animals actively 32–34 or passively 35,36 immunized with MuSK. In rabbits and mice repeatedly immunized with MuSK, mild weakness has been observed along with mild electrophysiologic evidence of disordered neuromuscular transmission 32. In addition, in mice passively injected with human AMM IgG repeatedly over 14 days (total of 0.68 g), mild-moderate weakness occurred in conjunction with reduced MuSK and AChR staining and reduced registration between nerve terminals and endplates at NMJs 35.

In contrast, the form of EAMM induced in Lewis rats by a single immunization with 100 ug of xenogeneic N-MuSK 60 is extremely severe with 100% mortality by 27 days and very high anti-MuSK antibody titers (>1: 106). The animals exhibit marked weight loss and axial muscle wasting, the latter not described in the other models. As the disease progresses, the axial weakness/wasting leads to a striking kyphotic posture and eventually the inability of the forelimbs to lift the chest from the floor of the cage. It is of note that similar posture and gait abnormalities have been observed in adult mice in which MuSK expression was turned off using Cre recombinase-mediated MuSK gene deletion 17. The reproduction of all the characteristics of AMM in the current form of EAMM supports the hypothesis that the autoimmune response to MuSK in AMM is pathogenically important in this disease, rather than representing an epiphenomenon. Moreover, these observations highlight the potential usefulness of this model for studying the pathogenesis and future treatments of AMM.

It is unclear why the disease in the present study is so much more severe than that induced in the three previous studies involving active immunization. Possible factors include differences in species susceptibility to autoimmunity 37,38 or species differences in sensitivity to the anti-MuSK attack, perhaps related to differences in the safety factor of neuromuscular transmission 37,39. A third possibility relates to the differences in the antigens used to induce the disease and, hence, the epitope targets of the disease-inducing Abs. The MuSK 60 isoform, used as immunogen in the current study, appears to be an adult form of the protein 24, which may be an important target of the auto-Abs in EAMM and AMM. For the rabbit and mouse forms of EAMM, the immunogens have been either the fetal isoform or another splicing variant of the protein that is missing not only the 20 amino acid extra domain of MuSK 60 but also the entire third Ig domain 32,33,34.

Immunization with a lower dose of N-MuSK 60 resulted in lower titers of anti-N-MuSK 60 Abs (1:105) and less severe disease with a much lower mortality. The correlation between anti-N-MuSK 60 antibody titer and disease severity also supports the hypothesis that EAMM and AMM are the result of the action of the MuSK antibodies. The observation (Table 1) that the low-dose animals exhibit greater diminution in neuromuscular transmission (at least as measured in a distal extremity muscle), albeit at later times following the immunization, may simply relate to the differential effect observed on axial versus distal muscles in EAMM. However, the observation also raises the possibility that the weakness, weight loss and muscle wasting associated with the rapidly fatal high-dose disease may not solely be the consequence of reduced neuromuscular transmission per se, but rather that other physiologic activities at the NMJ may also play a role.

Within individual EAMM muscles, NMJs exhibit varying degrees of disruption. The architecture of some endplates is altered at the ultrastructural level by hypersegmentation consisting of multiple small axon terminals with marked simplification of post synaptic membranes (Fig. 7, Table 3). The nerve terminals at other NMJs are more severely affected, with complete or partial loss of these structures (Fig. 5, Table 2). In addition, some axons have an abnormal globular appearance and others exhibit local extension beyond the NMJ, or even frank terminal axon sprouting (Fig. 5). In some NMJs, there is misalignment between the presynaptic and postsynaptic portions of these synapses. The latter findings, some of which were also observed in the study of passive transfer of human AMM serum into mice 35 and in one of the three studies of AMM 40, suggest that there is abnormal “signaling” between nerve terminal and muscle endplate in both directions resulting in failure of maintenance of the mature synapse in these animals 41.

In addition, cholinesterase staining of teased muscle bundles from N-MuSK 60-immunized animals reveals segmented and dispersed cholinesterase-stained patches, away from the compact synaptic region (motor point) (Fig. 6) reminiscent of newly formed synapses, which raises the possibility that the antibody attack leads first to frank denervation at some NMJs with subsequent and, possibly ongoing, attempts at reinnervation. It is of special note that severe damage to the endplate membrane, as is seen in acute forms of EAMG and MG, shown early on in MG by Drachman and associates42, produces local cholinesterase spreading but minimal nerve terminal abnormalities and/or denervation/distant reinnervation. Hence, the antibody attack on MuSK appears to have wider ranging effects on the NMJ than is seen with the highly destructive antibody attack on the more abundant endplate AChRs in EAMG/MG.

The mechanism of the prominent axial muscle wasting in EAMM rats, also not seen in EAMG and MG, remains unclear. Both histologic and electrophysiologic studies in human AMM suggest that the muscle wasting is not the result of denervation but rather is the consequence of a myopathic process 40,43–45. Such observations support a role for MuSK in mediating trophic effects on muscle, perhaps through complex two-way communication between nerve and muscle at the NMJ. On the other hand, focal denervation with accompanying reinnervation, as suggested by some of the morphologic studies described above, might also lead to muscle wasting.

Finally, the observations presented here demonstrate that an immune attack on MuSK can result in weakness, muscle wasting and severe disruption of the architecture of both the postsynaptic and presynaptic portions of the mature NMJ, thereby supporting the hypothesis that, in addition to its role in the developing NMJ, MuSK plays a role in the maintenance and function of the mature structure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants to Dr. Richman from National Institutes of Health (R21NS071325-01), Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA114815), Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of California; grants to Dr. Ferns from Muscular Dystrophy Association; grants to Dr. Maselli from National Institutes of Health (R01NS049117-01), Muscular Dystrophy Association, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America and Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of California.

References

- 1.Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, Newsom-Davis J, Melms A, Vincent A. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med. 2001;7:365–368. doi: 10.1038/85520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evoli A, Tonali PA, Padua L, et al. Clinical correlates with anti-MuSK antibodies in generalized seronegative myasthenia gravis. Brain. 2003;126:2304–2311. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders DB, El Salem K, Massey JM, McConville J, Vincent A. Clinical aspects of MuSK antibody positive seronegative MG. Neurology. 2003;60:1978–1980. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065882.63904.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent A, Bowen J, Newsom-Davis J, McConville J. Seronegative generalised myasthenia gravis: clinical features, antibodies, and their targets. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou L, McConville J, Chaudhry V, et al. Clinical comparison of muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) antibody-positive and -negative myasthenic patients. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:55–60. doi: 10.1002/mus.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindstrom J. Is “seronegative” MG explained by autoantibodies to MuSK? Neurology. 2004;62:1920–1921. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129702.41868.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selcen D, Fukuda T, Shen XM, Engel AG. Are MuSK antibodies the primary cause of myasthenic symptoms? Neurology. 2004;62:1945–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000128048.23930.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:791–805. doi: 10.1038/35097557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burden SJ. Building the vertebrate neuromuscular synapse. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:501–511. doi: 10.1002/neu.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes BW, Kusner LL, Kaminski HJ. Molecular architecture of the neuromuscular junction. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:445–461. doi: 10.1002/mus.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burden SJ, Fuhrer C, Hubbard SR. Agrin/MuSK signaling: willing and Abl. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:653–654. doi: 10.1038/nn0703-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weatherbee SD, Anderson KV, Niswander LA. LDL-receptor-related protein 4 is crucial for formation of the neuromuscular junction. Development. 2006;133:4993–5000. doi: 10.1242/dev.02696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim N, Stiegler AL, Cameron TO, et al. Lrp4 is a receptor for Agrin and forms a complex with MuSK. Cell. 2008;135:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Luo S, Wang Q, et al. LRP4 serves as a coreceptor of agrin. Neuron. 2008;60:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kummer TT, Misgeld T, Sanes JR. Assembly of the postsynaptic membrane at the neuromuscular junction: paradigm lost. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong XC, Barzaghi P, Ruegg MA. Inhibition of synapse assembly in mammalian muscle in vivo by RNA interference. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:183–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesser BA, Henschel O, Witzemann V. Synapse disassembly and formation of new synapses in postnatal muscle upon conditional inactivation of MuSK. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrugia ME, Robson MD, Clover L, et al. MRI and clinical studies of facial and bulbar muscle involvement in MuSK antibody-associated myasthenia gravis. Brain. 2006;129:1481–1492. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings CG, Dyer SM, Burden SJ. Muscle-specific trk-related receptor with a kringle domain defines a distinct class of receptor tyrosine kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2895–2899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valenzuela DM, Stitt TN, DiStefano PS, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase specific for the skeletal muscle lineage: expression in embryonic muscle, at the neuromuscular junction, and after injury. Neuron. 1995;15:573–584. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopf C, Hoch W. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the muscle-specific kinase is exclusively induced by acetylcholine receptor-aggregating agrin fragments. Eur J Biochem. 1998;253:382–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiegler AL, Burden SJ, Hubbard SR. Crystal structure of the frizzled-like cysteine-rich domain of the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strochlic L, Cartaud A, Cartaud J. The synaptic muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) complex: new partners, new functions. Bioessays. 2005;27:1129–1135. doi: 10.1002/bies.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishi K, Agius MA, Richman DP. Differentiation-dependent expression of a novel splicing variant of muscle-specific kinase. Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Online Program No. 10.8. 2008; Jan 12, 2008. Ref Type: Internet Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richman DP, Nishi K, Morell S, Maselli RA, Agius MA. Acute Severe Model of Anti-Muscle Specific Kinase (MuSK) Myasthenia in Lewis Rats. (Abstract) Neurology. 2008;71:153. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richman DP, Gomez CM, Berman PW, Burres SA, Fitch FW, Arnason BG. Monoclonal anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies can cause experimental myasthenia. Nature. 1980;286:738–739. doi: 10.1038/286738a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez CM, Wollmann RL, Richman DP. Induction of the morphologic changes of both acute and chronic experimental myasthenia by monoclonal antibody directed against acetylcholine receptor. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1984;63:131–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00697195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez CM, Maselli RA, Groshong J, et al. Active calcium accumulation underlies severe weakness in a panel of mice with slow-channel syndrome. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6447–6457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06447.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maselli RA, Mass DP, Distad BJ, Richman DP. Anconeus muscle: a human muscle preparation suitable for in-vitro microelectrode studies. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:1189–1192. doi: 10.1002/mus.880141208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maselli RA, Dunne V, Pascual-Pascual SI, et al. Rapsyn mutations in myasthenic syndrome due to impaired receptor clustering. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:293–301. doi: 10.1002/mus.10433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jha S, Xu K, Maruta T, et al. Myasthenia gravis induced in mice by immunization with the recombinant extracellular domain of rat muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) J Neuroimmunol. 2006;175:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Punga AR, Lin S, Oliveri F, Meinen S, Ruegg MA. Muscle-selective synaptic disassembly and reorganization in MuSK antibody positive MG mice. Exp Neurol. 2011;230:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shigemoto K, Kubo S, Maruyama N, et al. Induction of myasthenia by immunization against muscle-specific kinase. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1016–1024. doi: 10.1172/JCI21545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole RN, Reddel SW, Gervasio OL, Phillips WD. Anti-MuSK patient antibodies disrupt the mouse neuromuscular junction. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:782–789. doi: 10.1002/ana.21371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole RN, Ghazanfari N, Ngo ST, Reddel SW, Phillips WD. Patient autoantibodies deplete postsynaptic Muscle Specific Kinase leading to disassembly of the ACh receptor scaffold and myasthenia gravis in mice. J Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christadoss P, Poussin M, Deng C. Animal models of myasthenia gravis. Clin Immunol. 2000;94:75–87. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Link H, Xiao BG. Rat models as tool to develop new immunotherapies. Immunol Rev. 2001;184:117–128. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood SJ, Slater CR. Safety factor at the neuromuscular junction. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:393–429. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niks EH, Kuks JB, Wokke JH, et al. Pre- and postsynaptic neuromuscular junction abnormalities in musk myasthenia. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:283–288. doi: 10.1002/mus.21642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ter Beek WP, Martinez-Martinez P, Losen M, et al. The effect of plasma from muscle-specific tyrosine kinase myasthenia patients on regenerating endplates. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1536–1544. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fambrough DM, Drachman DB, Satyamurti S. Neuromuscular junction in myasthenia gravis: decreased acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1973;182:293–295. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4109.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishii W, Matsuda M, Okamoto N, et al. Myasthenia gravis with anti-MuSK antibody, showing progressive muscular atrophy without blepharoptosis. Intern Med. 2005;44:671–672. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finsterer J. Turn/amplitude analysis to assess bulbar muscle wasting in MuSK positive myasthenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrugia ME, Kennett RP, Hilton-Jones D, Newsom-Davis J, Vincent A. Quantitative EMG of facial muscles in myasthenia patients with MuSK antibodies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.