Abstract

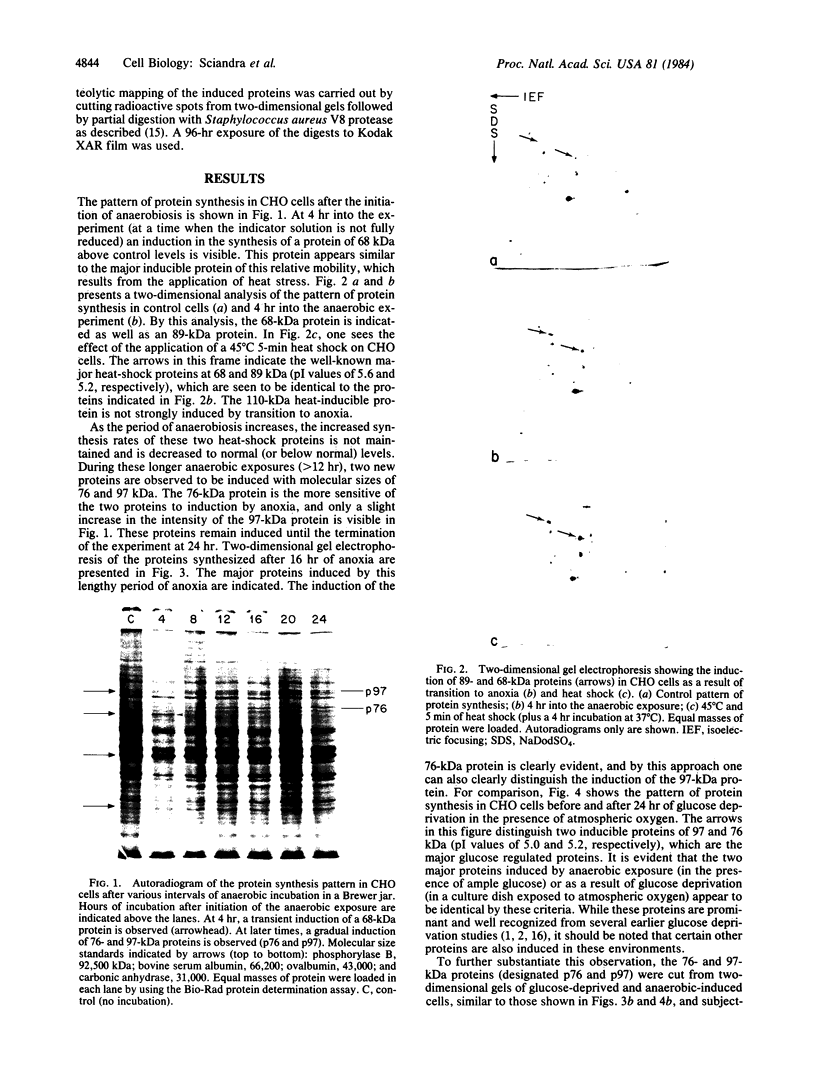

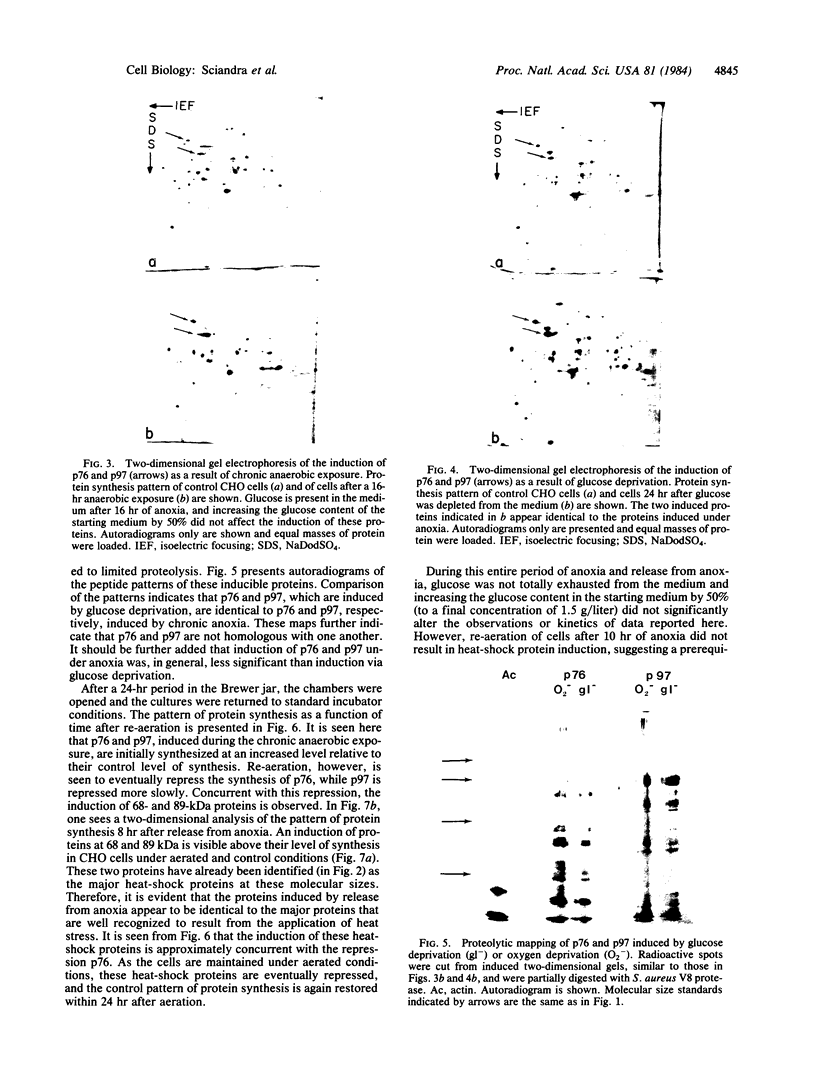

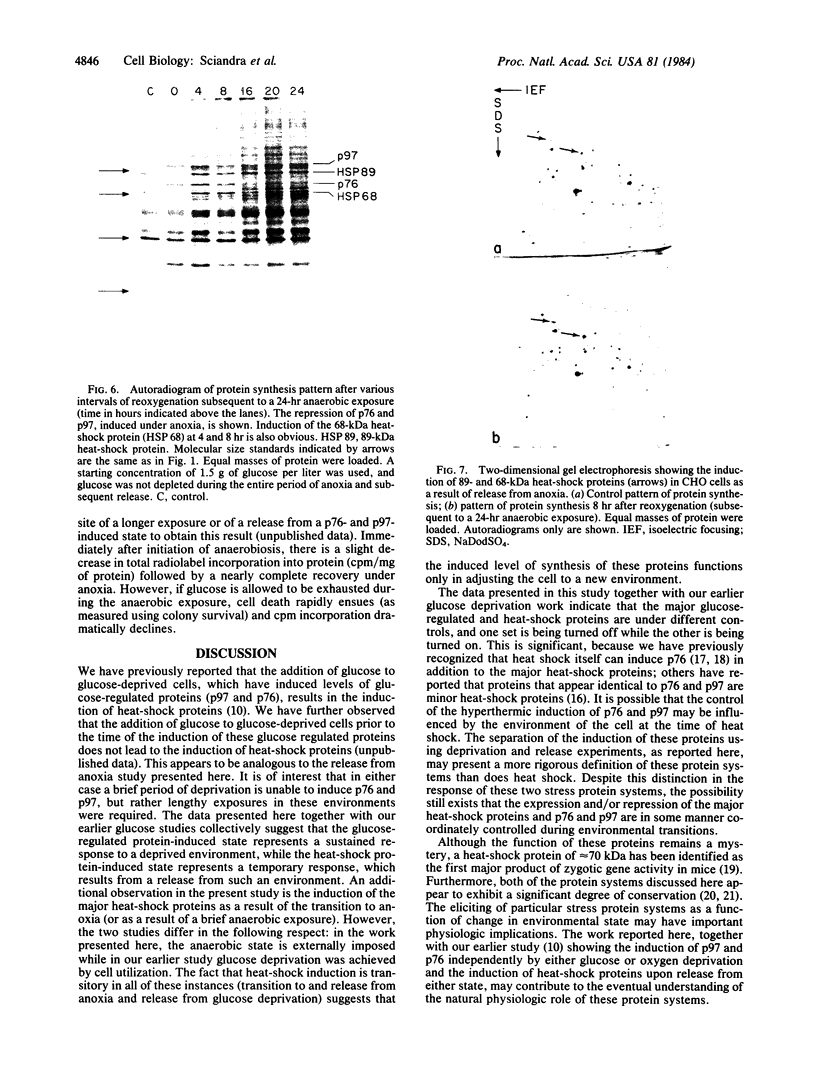

In this report we examine the effects of chronic anaerobic exposure and subsequent reoxygenation on protein synthesis patterns in Chinese hamster ovary cells. It is observed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (isoelectric focusing/NaDodSO4/PAGE) that the transition from an atmospheric environment to an anaerobic state transiently induces the major heat-shock proteins (at 68 and 89 kDa). As the period of anaerobiosis increases, this heat-shock induction disappears and a new set of proteins (at 76 and 97 kDa) is induced. By two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and partial proteolytic mapping, these new proteins, which are induced by anaerobic exposures exceeding 12 hr, are identical to 76 and 97 kDa (p76 and p97, respectively) proteins induced by extended periods of glucose deprivation (greater than 14 hr) when oxygen is present. Furthermore, the induction of these proteins under anoxia occurs in the presence of glucose, and increasing the glucose content of the starting media does not affect the induction. When anaerobic p76 and p97 induced cells are returned to atmospheric oxygen, p76 and p97 are repressed, while the heat-shock proteins are again transiently induced. This work further suggests the importance of deprivation and release environments in controlling the expression of these two stress protein systems. It is suggested that their natural expression may be determined by comparable circumstances.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson G. R., Marotti K. R., Whitaker-Dowling P. A. A candidate rat-specific gene product of the Kirsten murine sarcoma virus. Virology. 1979 Nov;99(1):31–48. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. R., Matovcik L. M. Expression of murine sarcoma virus genes in uninfected rat cells subjected to anaerobic sress. Science. 1977 Sep 30;197(4311):1371–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.197602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Bonner J. J. The induction of gene activity in drosophilia by heat shock. Cell. 1979 Jun;17(2):241–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaude O., Babinet C., Morange M., Jacob F. Heat shock proteins, first major products of zygotic gene activity in mouse embryo. Nature. 1983 Sep 22;305(5932):331–333. doi: 10.1038/305331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland D. W., Fischer S. G., Kirschner M. W., Laemmli U. K. Peptide mapping by limited proteolysis in sodium dodecyl sulfate and analysis by gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1977 Feb 10;252(3):1102–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerweck L. E., Nygaard T. G., Burlett M. Response of cells to hyperthermia under acute and chronic hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res. 1979 Mar;39(3):966–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger B. L., Repasky E. A., Lazarides E. Synemin and vimentin are components of intermediate filaments in avian erythrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1982 Feb;92(2):299–312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman S. D., Glover C. V., Allis C. D., Gorovsky M. A. Heat shock, deciliation and release from anoxia induce the synthesis of the same set of polypeptides in starved T. pyriformis. Cell. 1980 Nov;22(1 Pt 1):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard B. D., Lazarides E. Copurification of actin and desmin from chicken smooth muscle and their copolymerization in vitro to intermediate filaments. J Cell Biol. 1979 Jan;80(1):166–182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.80.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P. M., Schlesinger M. J. Antibodies to two major chicken heat shock proteins cross-react with similar proteins in widely divergent species. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Mar;2(3):267–274. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J., Bernier D., Chrétien P., Nicole L. M., Tanguay R. M., Marceau N. Synthesis and degradation of heat shock proteins during development and decay of thermotolerance. Cancer Res. 1982 Jun;42(6):2457–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. S., Delegeane A., Scharff D. Highly conserved glucose-regulated protein in hamster and chicken cells: preliminary characterization of its cDNA clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Aug;78(8):4922–4925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell P. H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975 May 25;250(10):4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouysségur J., Shiu R. P., Pastan I. Induction of two transformation-sensitive membrane polypeptides in normal fibroblasts by a block in glycoprotein synthesis or glucose deprivation. Cell. 1977 Aug;11(4):941–947. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciandra J. J., Subjeck J. R. The effects of glucose on protein synthesis and thermosensitivity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1983 Oct 25;258(20):12091–12093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seip W. F., Evans G. L. Atmospheric analysis and redox potentials of culture media in the GasPak System. J Clin Microbiol. 1980 Mar;11(3):226–233. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.3.226-233.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu R. P., Pouyssegur J., Pastan I. Glucose depletion accounts for the induction of two transformation-sensitive membrane proteinsin Rous sarcoma virus-transformed chick embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Sep;74(9):3840–3844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subjeck J. R., Sciandra J. J., Johnson R. J. Heat shock proteins and thermotolerance; a comparison of induction kinetics. Br J Radiol. 1982 Aug;55(656):579–584. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-55-656-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasovic S. P., Steck P. A., Heitzman D. Heat-stress proteins and thermal resistance in rat mammary tumor cells. Radiat Res. 1983 Aug;95(2):399–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J., Garrels J. I., Thomas G. P., Lin J. J., Feramisco J. R. Biochemical characterization of the mammalian stress proteins and identification of two stress proteins as glucose- and Ca2+-ionophore-regulated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1983 Jun 10;258(11):7102–7111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]