Abstract

Cryptococcus neoformans , the main causative agent of cryptococcosis, is a fungal pathogen that causes life-threatening meningoencephalitis in immunocompromised patients. To date, there is no vaccine or immunotherapy approved to treat cryptococcosis. Cell- and antibody-mediated immune responses collaborate to mediate optimal protection against C. neoformans infections. Accordingly, we identified cryptococcal protein fractions capable of stimulating cell- and antibody-mediated immune responses and determined their efficacy to elicit protection against cryptococcosis. Proteins were extracted from C. neoformans and fractionated based on molecular mass. The fractions were then evaluated by immunoblot analysis for reactivity to serum extracted from protectively immunized mice and in cytokine recall assays for their efficacy to induce pro-inflammatory and Th1-type cytokine responses associated with protection. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed a number of proteins with roles in stress response, signal transduction, carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid synthesis, and protein synthesis. Immunization with select protein fractions containing immunodominant antigens induced significantly prolonged survival against experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis. Our studies support using the combination of immunological and proteomic approaches to identify proteins that elicit antigen-specific antibody and Th1-type cytokine responses. The immunodominant antigens that were discovered represent attractive candidates for the development of novel subunit vaccines for treatment and/or prevention of cryptococcosis.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcosis, ImmunoProteomics, Surface proteins, Cytoplasmic proteins, Vaccination

1 Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans, the main causative agent of cryptococcosis, is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes life-threatening meningoencephalitis in immunocompromised hosts (i.e., individuals infected with HIV [1–5], receiving corticosteroid therapy [6–8], with lymphoproliferative disorders [9–12], and organ transplant recipients [13]). Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is the leading disseminated fungal infection in AIDS patients worldwide, with a global estimation of one million cases per annum resulting in approximately 620,000 deaths [14]. Individuals who are successfully treated for AIDS-associated cryptococcal meningitis may require life-long maintenance antifungal therapy due to a high relapse rate [15, 16]. Immune reconstitution due to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has resulted in a significant decline in AIDS-associated cryptococcal infection [17, 18]. However, the use of HAART to treat HIV infection has been associated with the development of C. neoformans-related immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) which is also life-threatening [19]. Moreover, the clinical relevance of invasive cryptococcal disease continues to gain prominence due to the continuing AIDS epidemic coupled with increased usage of immunosuppressive drugs to prevent organ rejection or to treat autoimmune diseases. There are currently no licensed vaccines available to prevent cryptococcosis, and the efficacy of antifungal drugs is diminishing due to increased drug resistance, drug toxicity and the inability of the typical immune-suppressed host defenses to assist in the antifungal response. Hence, there remains an urgent need for therapies and vaccines to combat cryptococcosis.

Cell-mediated immunity (CMI) by Th1-type CD4+ T cells is generally believed to be the primary host defense response against cryptococcosis, as evidenced clinically by the high susceptibility of individuals with reduced CMI to C. neoformans infections [1–13]. Th1-type CD4+ T cells mediate protective anti-cryptococcal immune responses through the generation of Th1-type cytokine responses characterized by the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). These cytokines, in turn, induce lymphocyte and phagocyte recruitment, and activation of anticryptococcal delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses, resulting in increased cryptococcal uptake and killing by effector phagocytes [20–26]. While the contribution of antibody-mediated immunity (AMI) for protecting individuals against cryptococcosis remains uncertain, there are numerous studies highlighting the effectiveness of AMI or individual antibodies to mediate protection against cryptococcosis [27–31]. Thus, optimal protection against cryptococcosis undoubtedly requires the combined efforts of cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immune responses.

Immunogenic cryptococcal antigens are often pre-selected for analysis based on their serological activity [32–35]. However, proteins that are immunodominant for B cell epitopes may not necessarily be immunodominant for T cell epitopes. Therefore, where immune recognition and protection are mediated predominantly by T cells, strategies should be implemented to identify proteins that also induce antigen-specific T cell responses. Consequently, we elected to use a combined immunological and proteomic approach to screen complex mixtures of C. neoformans proteins to identify proteins that are immunodominant based on serologic reactivity and on their capability to elicit pro-inflammatory and Th1-type cytokine responses against C. neoformans antigens. We also tested the efficacy of selected protein fractions to protect mice against experimental pulmonary C. neoformans infection and identified proteins within these cryptococcal fractions that may serve as candidates for vaccine development.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Murine Model

Female BALB/c (H-2d) mice, 4 to 6 weeks of age (National Cancer Institute/Charles River Laboratories), were used throughout these studies. Mice were housed at The University of Texas at San Antonio Small Animal Laboratory vivarium and handled according to guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Pulmonary C. neoformans infections were initiated by nasal inhalation as previously described [36]. Briefly, anesthetized mice received an initial inoculum of 1 × 104 CFU of C. neoformans strain H99γ or heat-killed C. neoformans strain H99 yeasts in 50 μl of sterile PBS or sterile PBS alone and allowed 100 days to resolve the infection. Subsequently, the immunized mice received a second experimental pulmonary infection with 1 × 104 CFU of C. neoformans strain H99 in 50 μl of sterile PBS. The inocula used for immunizations and secondary challenge were verified by quantitative culture on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) agar. The mice were fed ad libitum and were monitored by inspection twice daily. Serum was extracted from mice by cardiac puncture on day 14 post-secondary inoculation and used for immunoblot analysis.

2.2 Strains and Media

C. neoformans strains H99 (serotype A, Mat α) and H99γ (an IFN-γ producing C. neofromans strain derived from H99 [37]) were revived from 15% glycerol stocks stored at −80°C prior to use in these experiments. Both strains were maintained on YPD media (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 2% Bacto agar). Yeast cells were grown for 18–20 h at 30°C with shaking in YPD broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD), collected by centrifugation, washed three times with sterile PBS, and viable yeast quantified using trypan blue dye exclusion in a hemacytometer.

2.3 Protein Extraction

C. neoformans strain H99 yeast was incubated overnight in liquid YPD medium at 30°C. The yeast were collected by centrifugation, washed twice in sterile PBS and divided into two fractions, one for the extraction of cell wall associated (CW) proteins as previously described [35] and the other for the isolation of cytoplasmic (CP) proteins. Cell pellets intended for the isolation of CW proteins were suspended in ammonium carbonate buffer, pH 8.4, containing 1% (v/v) beta-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C with gentle agitation. β-ME treatment releases disulphide bridge-linked and non-covalently, but not covalently, linked cell-wall associated proteins. After treatment, the cells were collected by centrifugation and the supernatant filtered sterilized through 0.45-μM filters (Nalgene Nunc International Corp., Rochester, NY). Cell pellets intended for the isolation of CP proteins were suspended in YeastBuster™ Protein Extraction Reagent containing tris(hydroxypropy)phosphine (THP) (Nalgene, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and incubated for 45 min at 30°C with gentle agitation. After treatment, the cells were collected by centrifugation and the supernatant containing CP proteins filter sterilized using a 0.45-μM filter (Nalgene Nunc International Corp.). The supernatants were then individually desalted and concentrated by centrifugation through an Amicon Ultrafree-15 (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) centrifugal filter device. Protein content was estimated using the RC DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Subsequently, the proteins were further concentrated and non-protein contaminants removed using the ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4 Gel Free Fractionation and One-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Proteins were separated into multiple fractions based on molecular mass using a GELFREE™ 8100 Fractionation System (Expedeon Inc., San Diego, CA) containing pre-formulated HEPES running buffer and Tris Acetate sample buffer (Expedeon Inc.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. C. neoformans CW and CP proteins were dissolved in sample buffer and loaded into individual loading chambers of an 8% Tris-Acetate cartridge designed to separate proteins in the mass range of 3.5–150 kDa, with resolution between 35 kDa and 150 kDa. The instrument was automatically paused at predefined intervals and the liquid fraction removed with a pipette. The sequence was then restarted and the process continued to collect the next size-based fraction. This process was repeated until all fractions were collected. After recovery of 12 individual CW and CP fractions, standard one-dimensional gel electrophoresis (1-DE) was performed using 12.5% SDS-PAGE Criterion Precast Gels (BioRad). Protein separation was carried out for 55 min at 200V in Tris/glycine/SDS (TGS) running buffer (BioRad) using Criterion electrophoresis equipment (BioRad). Proteins in the gels were stained using SYPRO Ruby protein gel stain (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) and protein spots detected using a ChemiDoc XRS Camera and Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad).

2.5 Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (ReadyStrip IPG, 11cm, pH 4–7, Bio-Rad) were rehydrated in 200 μl of rehydration/sample buffer (Bio-Rad; 8 M urea, 2% CHAPS, 50 mM DTT, 0.2% w/v Bio-lite 3/10 ampholytes, and trace bromophenol blue) containing 200 μg of the C. neoformans pooled CW fractions (fractions 1, 8, 10, 11 and 12) or one CP fraction (fraction 10) protein preparation. Isoelectric focusing (IEF) was carried out using PROTEAN IEF (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: Step 1, 250 V for 20 min.; Step 2, ramped to 8000 V over 2.5 h, and Step 3, 8000 for a total of 30,000 V/h. Strips were then placed into equilibration buffer (Bio-Rad; 6 M urea, 2% SDS, 375 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 20% glycerol, 2% DTT) for 15 min. Disulfide groups were subsequently alkylated by 10-min treatment with equilibration buffer of the same composition substituting 2.5% w/v iodacetamide instead of DTT. Equilibrated IPG strips were then drained and placed on the top of 12.5% SDS-PAGE Criterion Precast Gels (Bio-Rad) and fixed using hot ReadyPrep Overlay agarose (Bio-Rad). The separation of proteins in the second dimension was carried out for 55 min at 200 V in Tris/glycine/SDS (TGS) running buffer (Bio-Rad) using Criterion electrophoresis equipment (Bio-Rad). Proteins in the gels were stained using Sypro Ruby Red (Molecular Probes Inc.) or, alternatively, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for immunoblot analysis.

2.6 Immunoblot Analysis

Resolved proteins were transferred to Hybond-P PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) using a Semi-Dry Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membranes were subsequently blocked using 5% non-fat milk in 20 mM Tris containing 500 mM NaCl (Tris-buffered saline) and 1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature The blocking solution was then discarded and the membranes incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:200 dilution of banked immune sera. The immune sera was derived from mice immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ or heat-killed C. neoformans on day 14 post-secondary challenge with wild-type (WT) C. neoformans strain H99 [35]. BALB/c mice immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ mount sterilizing immune responses against a subsequent challenge with WT C. neoformans whereas mice vaccinated with heat-killed C. neoformans succumb to rechallenge [35]. The membranes were then washed six times in TBS-T and antibody binding detected by the addition of goat anti-mouse IgG HRP-conjugated antibody (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL) diluted 1:1000 in TBS-T containing 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature. After six washes in TBS-T, the membranes were briefly incubated with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.) and protein spots detected using a ChemiDoc XRS Camera and Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad).

2.7 Cytokine Recall Analysis

Splenocytes (1 × 106/well) derived from female BALB/c mice vaccinated with C. neoformans strain H99γ or sterile PBS on day 60 post-immunization were cultured in RPMI complete media with individual protein fractions (50 μg each), hen egg lysozyme (HEL; 1 μg/ml), or concanavalin A (Con A; 1 μg/ml) as negative and positive controls, respectively, at 37°C and 5% CO2 in 96 well round bottom culture plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Endotoxin content of the CW and CP proteins fractions was determined by using a Limulus amebocyte lysate kit (QLC-1000, Lonza, Walkersville, MD) and found to be minimal (less than 1 EU/μg protein). The culture supernatants were collected after 24 h and cytokine expression assayed using the Bio-Plex Protein Array System (Luminex-based technology) from Bio-Rad as previously described [36].

2.8 Excision, Trypsinization, and Identification of protein bands by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

Peptide identifications were accomplished at the Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Individual spots of interest were excised manually from the gel using a sterile scalpel following 2-DE. The spots were destained in 40 mM NH4CO3/50% acetonitrile, dehydrated in acetonitrile and digested overnight at 37 °C with trypsin (Promega, sequencing grade) in 40 mM NH4CO3/10% acetonitrile. The tryptic peptides were extracted with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) followed by 0.1% TFA/50% acetonitrile. The combined extracts were dried by vacuum centrifugation and resuspended in 0.5% TFA. The digests were analyzed by capillary HPLC-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectra (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) using a Thermo Fisher LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer fitted with a New Objective PicoView 550 nanospray interface. On-line HPLC separation of the digests was accomplished with an Eksigent NanoLC micro HPLC: column, PicoFrit™ (New Objective; 75 μm i.d.) packed to 10 cm with C18 adsorbent (Vydac; 218MS 5 μm, 300 Å); mobile phase A, 0.5% acetic acid (HAc)/0.005% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA); mobile phase B, 90% acetonitrile/0.5% HAc/0.005% TFA; gradient 2 to 42% B in 30 min; flow rate, 0.4 μl/min. MS conditions were: ESI voltage, 2.9 kV; isolation window for MS/MS, 3; relative collision energy, 35%; scan strategy, survey scan followed by acquisition of data dependent collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra of the seven most intense ions in the survey scan above a set threshold. The MS datasets were searched against the NCBInr database [NCBInr 20130102 (22,378,659 sequences; 7,688,401,091 residues)] by means of Mascot (version 2.4.1; Matrix Science, London, UK). Methionine oxidation and cysteine carbamidomethylation were considered as variable modifications for all searches. Scaffold™ 4.0 (Proteome Software, Portland, OR) was used to conduct an X! Tandem subset search of the Mascot data followed by cross-correlation of the results of both searches. The Scaffold confidence levels for acceptance of peptide assignments and protein identifications were 95% and 99%, respectively.

2.9 Survival Analysis after Vaccination with Protein Fractions

Mice were mock-immunized with 50 μl of sterile endotoxin-free PBS (HyClone Lab. Inc, Logan, UT), 100 μg of individual CW protein fractions (fractions 1, 8, 10, 11, and 12), or CP protein fractions (fractions 1, 4, and 10) in 50 μl of sterile PBS. We chose to immunize mice intranasally as this is the most likely route of introduction of C. neoformans into humans [38]. Mice were immunized three times, with four week intervals between each immunization. Ten days following the final immunization, mice received 1 × 104 C. neoformans by nasal inhalation as previously described [36]. Survival was monitored twice daily, and mice that appeared moribund or not maintaining normal habits (grooming) were sacrificed.

2.10 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare cytokine results using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Survival data were analyzed using the log-rank test (GraphPad Software). Significant differences were defined as P < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Fractionation and identification of immunogenic cryptococcal cell wall associated and cytoplasmic proteins

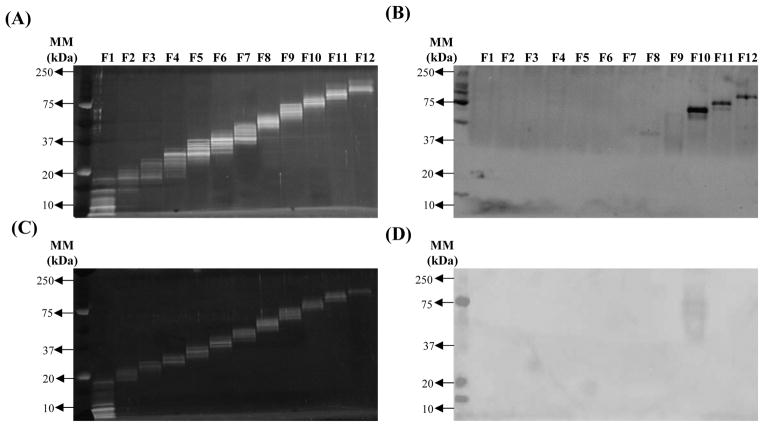

C. neoformans CW and CP protein fractions (12 CW and 12 CP protein fractions) were resolved by 1-DE for visualization of individual CW (Figure 1A) and CP (Figure 1C) fractions. Subsequently, immunoblot analysis was performed using banked immune sera collected on day 14 post-secondary challenge from protectively or non-protectively immunized mice [35] in order to identify potentially immunodominant cryptococcal protein fractions. Figure 1B demonstrates that fractions 1, 8, 10, 11 and 12 of the CW protein fractions were found to contain immunogenic proteins. C. neoformans CW fractions 1 and 8 consistently exhibited less intense immunoblot responses, suggesting a lower level of immune reactivity with sera, in contrast to the distinct sharp bands of fractions 10, 11, and 12 (Figure 1B). Only one CP protein fraction, fraction 10, was observed to contain immunogenic proteins (Figure 1D). The immunoblot response of CP protein fraction 10 was consistently lighter compared to CW fractions 10, 11, and 12. Altogether, the immunoblot analysis utilizing sera from protectively immunized mice identified five out of 12 CW protein fractions and one out of 12 CP fractions as containing potentially immunogenic cryptococcal proteins. We observed no immune reactivity against CW or CP protein fractions using sera from non-protectively immunized mice (data not shown), similar to previous reports [35].

Figure 1. Fractionation of C. neoformans cell wall associated proteins and cytoplasmic proteins.

Cell wall associated (CW) and cytoplasmic (CP) proteins extracted from C. neoformans were separated into twelve fractions based on molecular mass, resolved using 1-DE, and stained using SYPRO Ruby Red to visualize cell wall associated (A) and cytoplasmic (C) protein fractions. In parallel, protein fractions were separated by 1-DE and then transferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblot analysis of C. neoformans cell wall associated (B) and cytoplasmic (D) protein fractions was conducted using pooled serum taken on day 14 post-secondary infection of mice immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ. The results shown are representative of four experiments using pooled banked serum of three separate mouse studies per time point.

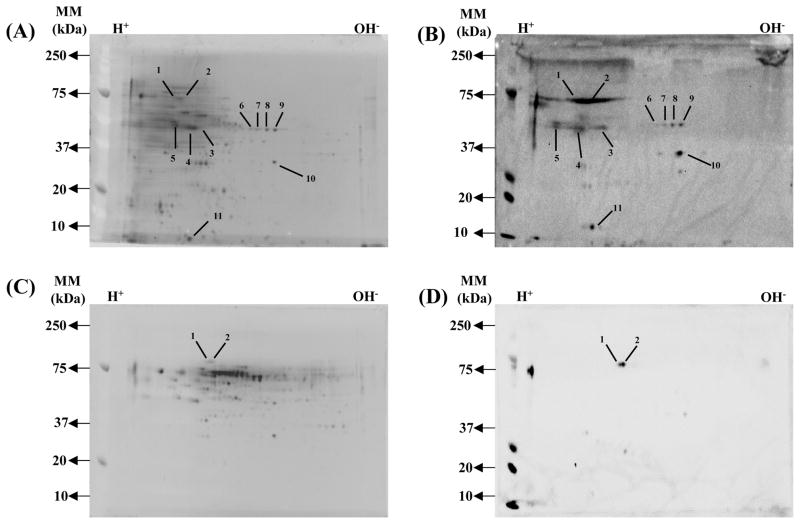

To identify specific proteins that are immune reactive with sera from protectively immunized mice, pooled CW protein fractions (1, 8, 10, 11 and 12) and CP fraction 10 protein were separately resolved by 2-DE (Figures 2A and 2C); immunoblot analysis was performed using immune sera collected on day 14 post-secondary challenge from protectively or non-protectively immunized mice. A total of 16 and two immunodominant proteins were identified in the CW and CP protein fraction, respectively (Figures 2B and 2D). A summary of the identified immunodominant CW and CP proteins is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2. 2-DE profile and immunoblot analysis of C. neoformans cell wall associated proteins and cytoplasmic proteins.

Pooled cell wall protein fractions (1, 8, 10, 11 and 12) and cytoplasmic fraction 10 were separated in the first dimension using a pI 4–7 IPG strip and in the second dimension using a 12.5% polyaccrylamide gel. Following 2-DE, the proteins on one gel were stained with SYPRO Ruby: (A) cell wall fractions; (C) 2 cytoplasmic fractions. Proteins in separate gels were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated with pooled serum taken on day 14 post-secondary infection from mice immunized using C. neoformans strain H99γ: (B) cell wall fractions; (D) cytoplasmic fraction. Numbered spots represent immunogenic proteins whose identities are given in Table 1. Protein spot selection was determined following performing three separate 2-DE and immunoblot experiments using pooled serum from two separate experiments to ensure reproducibility of results. Peptide identification by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS was repeated twice.

Table 1.

Immunodominant C. neoformans proteins identified by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS after 2-DE

| Spot No. | Protein Name1 | MW (kDa)2 | Accession Number3 | Unique Peptides4 | Sequence Cov. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall proteins | |||||

| 1 | Heat shock protein | 72 | AFR94464 | 5 | 9 |

| 2 | Hypothetical protein | 72 | AFR92468 | 4 | 9 |

| 2 | Chaperone | 65 | AFR92237 | 4 | 7 |

| 2 | Heat shock cognate-4 | 70 | AFR97929 | 6 | 15 |

| 3 | Saccharopine dehydrogenase | 43 | AFR94627 | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 48 | AFR93622 | 4 | 10 |

| 4 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | 49 | AFR97782 | 3 | 9 |

| 5 | Hypothetical protein | 52 | AFR95434 | 2 | 4 |

| 5 | FOF1 ATP synthase subunit beta | 59 | AFR96238 | 8 | 18 |

| 5 | LPD1 | 55 | AAN75183 | 6 | 13 |

| 6 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 48 | AFR93622 | 4 | 11 |

| 7 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 48 | AFR93622 | 4 | 10 |

| 8 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 48 | AFR93622 | 6 | 16 |

| 9 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 48 | AFR93622 | 7 | 18 |

| 10 | Dehydratase family | 34 | AFR93231 | 2 | 8 |

| 10 | Hypothetical protein | 33 | AFR97470 | 2 | 8 |

| 10 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | 33 | AFR93941 | 5 | 19 |

| 11 | Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase | 25 | AFR97119 | 2 | 8 |

| Cytoplasmic proteins | |||||

| 1 | Heat shock protein 90 | 78 | AAN76525 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Heat shock protein 70 | 74 | AFR98682 | 4 | 9 |

All proteins were identified with 100% probability in Scaffold

Molecular weight of NCBInr database entry

Accession numbers of NCBInr database entry

Peptides assigned with ≥ 95% confidence in Scaffold.

3.2 Identification of protein fractions that induce Th1-type cytokine recall responses

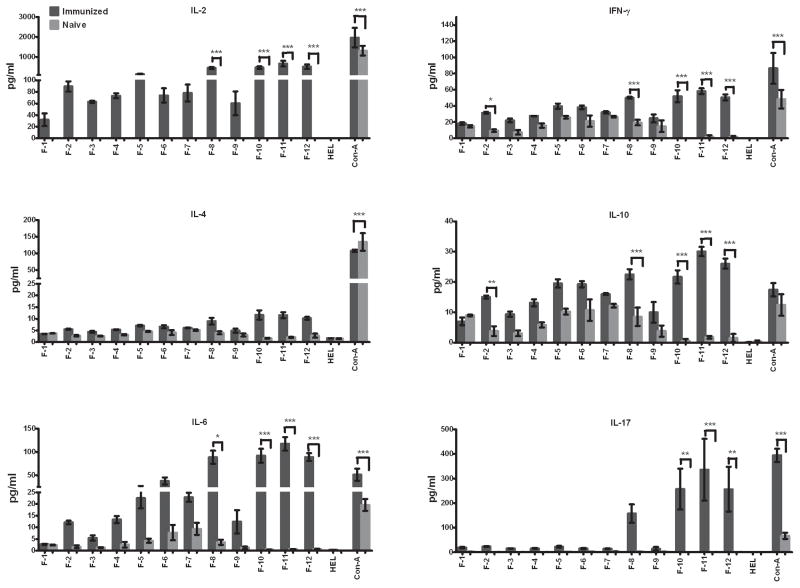

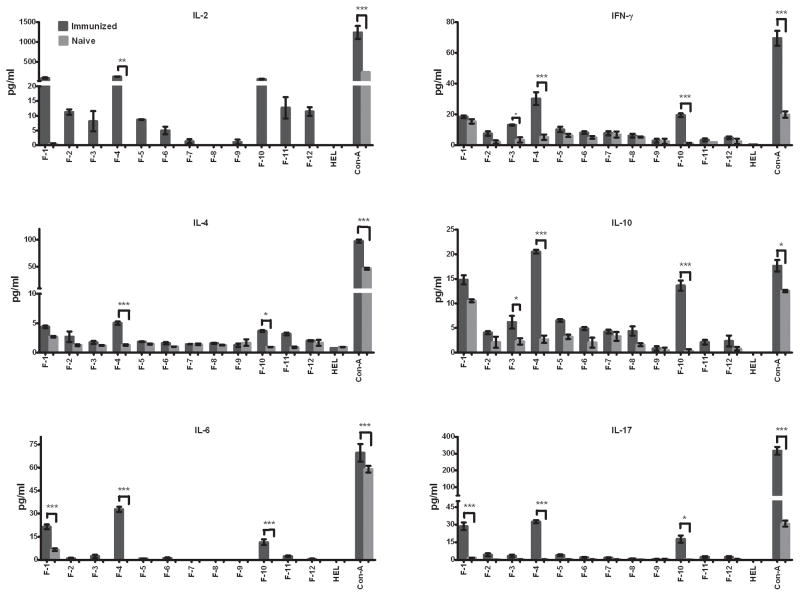

We postulated that serum antibodies generated in mice protectively immunized against pulmonary C. neoformans infection may be suitable for identifying immunodominant cryptococcal proteins with the potential to induce protective anti-cryptococcal immune responses. However, proteins that are immunodominant for B cells may not necessarily be immune dominant for T cells and induce putatively protective Th1-type cell-mediated immune responses against C. neoformans. Thus, we assessed the potential of each cryptococcal protein fraction to elicit Th1-type cytokine responses. To determine the presence of T cell reactive antigens, splenocytes from mock-immunized mice or mice immunized with H99γ were taken on day 14 post secondary inoculation. The splenocytes were then cultured in media containing each individual protein fraction and either hen egg lysozyme (HEL) or concanavalin A (Con A) as negative and positive controls, respectively, for 24 h and the supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis. Robust Th1-type (IL-2 and IFN-γ) and pro-inflammatory (IL-6 and IL-17) cytokine responses to CW fractions 8, 10, 11, and 12 (Figure 3) and to CP protein fractions 1, 4, and 10 (Figure 4) were observed following culture of splenocytes derived from C. neoformans strain H99γ immunized, but not mock-immunized mice. No significant pro-inflammatory or Th1-type cytokine production was induced by any other fractions. Th2-type (IL-4, and IL-10) cytokine expression of CW fractions was overall low (Figure 3). Significant increased expression of IL-4 was not observed with any of the splenocyte cultures stimulated with individual CW protein fractions (Figure 3). In contrast, cultures of splenocytes derived from immunized mice stimulated with CP protein fractions 4 and 10 showed significantly increased, albeit low, levels of IL-4 expression compared to cultures of cells derived from mock-infected mice (Figure 4). Significant increased levels of IL-10 were observed in cultures of splenocytes from H99γ immunized mice exposed to CW protein fractions 2, 8, 10, 11 and 12 (Figure 3) and CP protein fractions 1, 4 and 10 compared to cultures of cells from mock-immunized mice (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Cytokine recall responses to cell wall associated protein fractions.

Splenocytes derived from BALB/c mice protectively immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ or mock (PBS) immunized mice were cultured in triplicate wells with individual CW protein fractions, Hen egg lysozyme or concanavalin A as negative and positive controls, respectively, for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, culture supernatants were collected and processed individually for cytokine analysis. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. * significantly different, P < 0.05.

Figure 4. Cytokine recall responses to cytoplasmic protein fractions.

Splenocytes derived from BALB/c mice immunized with sterile PBS or protectively immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ were cultured in triplicate wells with individual CP protein fractions, HEL or Con-A for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. The culture supernatants were then collected and individually processed for cytokine analysis. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. * significantly different, P < 0.05.

3.3 Efficacy of C. neoformans protein fractions to induce protective immunity against experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis

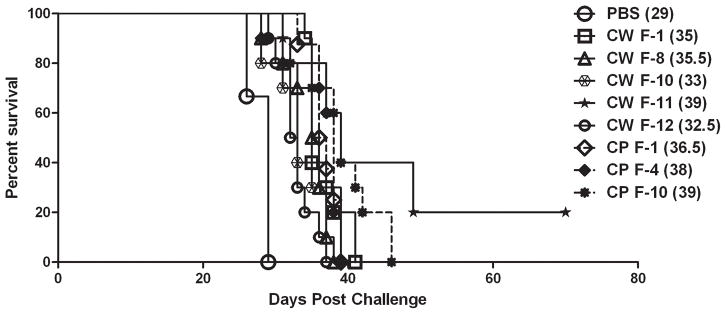

BALB/c mice were immunized with individual CW protein fractions (fractions 1, 8, 10, 11, or 12), three individual CP protein fractions (fractions 1, 4, or 10), or sterile endotoxin-free PBS (mock-immunized) as a control, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Ten days following the final immunization, mice were challenged with C. neoformans by nasal inhalation and survival (morbidity) monitored daily. We observed 100% mortality with a median survival time of 29 days in mock-immunized mice challenged with C. neoformans strain H99 (Figure 5). In contrast, prolonged survival against pulmonary C. neoformans infection was observed in mice immunized with all CW and CP protein fractions tested; albeit at varying levels of protection. The greatest protection against pulmonary cryptococcosis was observed in mice immunized with CW protein fraction 11. The survival study was terminated at day 70 and the two remaining mice from the CW fraction 11 immunized group were sacrificed and the fungal burden in the lungs and brain determined. No viable cryptococci were detected following culture of whole brain homogenates from surviving mice, suggesting either a lack of dissemination to or clearance of yeast from brain tissues. However, 2 × 104 CFU/ml and 2.6 × 104 CFU/ml was observed in lung tissue of the surviving two mice, respectively; this is a level of pulmonary infection that is similar to the initial inoculum of 1× 104 CFU C. neoformans strain H99.

Figure 5. Protection against experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis following immunization.

BALB/c mice were immunized with individual cell wall (CW) associated or cytoplasmic (CP) protein fractions (100 μg each) in 50 μl of sterile PBS or mock-immunized with PBS by nasal inhalation. Mice were then challenged with 1 × 104 CFU of C. neoformans strain H99 by nasal inhalation. Survival was monitored twice daily and mice that appeared moribund or not maintaining normal habits (grooming) were sacrificed. Survival data shown are of one experiment using ten mice per experimental group. Differences in survival rates of all immunized groups were found to be statistically significant compared to PBS immunized group (P < 0.05). The median day of survival for each group is given in parenthesis.

4 Discussion

The number of individuals at exceptionally high risk for developing cryptococcosis is predicted to increase due to the ongoing AIDS epidemic coupled with an increased use of immunosuppressive drugs intended to prevent organ rejection or treat autoimmune diseases. Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that immunization with C. neoformans strain H99γ elicits protective immunity against an otherwise lethal pulmonary challenge with C. neoformans [35]. Those studies showed that significantly elevated levels of C. neoformans-specific antibodies that were of a protective isotype were present in serum derived from mice protectively immunized with C. neoformans strain H99γ compared to mice non-protectively immunized with heat-killed C. neoformans prior to challenge [35]. We hypothesized that serum from protectively immunized mice could be used to identify cryptococcal CW and CP protein fractions that contain immunodominant protein antigens. Indeed, although 12 CW and 12 CP fractions were evaluated, the results reported here demonstrate that serum obtained from protected mice was immune-reactive with a total of five CW and one CP protein fraction.

Although the incidence of cryptococcal disease is most notable in individuals with suppressed cell-mediated immune responses, patients with defects in antibody-mediated immunity (AMI) such as hypogammaglobulinemia and hyper-IgM syndrome also have an increased likelihood of developing cryptococcosis [39–41]. Antibodies generated against C. neoformans have been demonstrated to have direct antifungal activity, inhibit Cryptococcus biofilm formation, increase the efficacy of antifungal therapy, help to eliminate immunosuppressive polysaccharide antigen from serum and tissues, modulate immune responses to prevent host damage, and mediate natural protection against cryptococcosis [27, 31, 42–52].

While the consensus is that protective anti-cryptococcal immune responses are dependent upon inducing protective CMI, AMI certainly contributes to this process. Previous studies in our lab demonstrated that serum antibody generated in mice protected against pulmonary C. neoformans infection could be used to identify immunodominant cryptococcal CW proteins with the potential to induce protective anti-cryptococcal immune responses [35]. However, proteins that are immunodominant for B cells may not likewise stimulate putatively protective Th1-type cytokine responses against C. neoformans. Thus, our previous strategy to screen C. neoformans protein fractions for those that are immunoreactive against serum antibody [35] was extended to select for CW and CP protein fractions that also stimulate protective Th1-type cytokine responses. Experimental results have also suggested that Th17-type responses and IL-17A production, specifically, are important for modulating survival against cryptococcosis [53, 54]. A significant induction of lung IL-17A was observed in mice vaccinated against a lethal C. neoformans challenge [36, 55, 56]. Cytokine recall analysis demonstrated that while CW fraction 1 contained potentially immunodominant proteins, based on our immunoblot analysis, CW protein fractions 8, 10, 11 and 12 elicited significant pro-inflammatory (IL-6 and IL-17), and Th-1 type (IL-2 and IFN-γ) cytokine responses. CP protein fraction 10 was observed to be immune reactive against sera from protectively immunized mice and additionally to stimulate pro-inflammatory and Th1-type cytokine recall responses. In addition, cytoplasmic protein fractions 1 and 4, which were not identified in our immunoblot analysis, were also found to induce significant pro-inflammatory and Th1-type cytokine responses. Overall, these results support our assertion that proteins that are immune dominant for B cells may not likewise stimulate putatively protective Th1-type cytokine responses against C. neoformans, and vice versa. Nonetheless, the overriding justification for selecting protein fractions that elicited both antibody and Th1-type cytokine responses was that one or more of these fractions contain protein antigens that elicit protective immune responses against pulmonary cryptococcosis in mice; a question that was not addressed in our previous study [35]. Indeed, we observed significantly prolonged survival against an experimental pulmonary C. neoformans infection in mice immunized with individual protein fractions that elicited C. neoformans-specific antibody and Th1-type cytokine responses compared to mock-immunized mice. The use of specific proteins or protein combinations along with an appropriate adjuvant is likely to significantly enhance the observed protection; such studies are on-going in the laboratory. HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of immunodominant proteins within the fractions used in our immunization studies revealed a number of proteins with an undetermined function (hypothetical proteins) as well as proteins with roles in stress response, signal transduction, carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid synthesis, and protein synthesis. Interestingly, many of the CW associated immune dominant proteins identified in our analysis (i.e., phosphopyruvate hydratase and heat shock proteins) would be intuitively viewed as CP proteins. However, it is widely known that several cytosolic proteins are also associated with the cell wall of fungi [57–59]. Many proteins identified in the present study have previously been implicated in the virulence component of C. neoformans and other fungal pathogens [60–67].

Yeast respond to environmental stressors such as nutrient limitation, osmotic shock, and heat shock by the induction of a number of proteins identified in our analysis. Heat shock protein (hsp) 70 is highly abundant and immunogenic in vivo during pulmonary cryptococcosis [33, 34]. Hsp 90 has been shown to govern fungal resistance to a number of anti-fungal drugs, including azoles and echinocandins [60–63]. Mice vaccinated with recombinant Candida hsp 90 elicited significant increases in Candida-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in both serum and vaginal fluid [68]. Hsps have been observed to be highly abundant and immunogenic in other models of mycosis [64–66]; however, the efficacy of hsps to induce protective immune responses against fungal disease is not universal [69]. Nonetheless, inhibition of a fungal pathogen’s ability to enhance its production of hsps in response to stressful conditions encountered in vivo is a plausible strategy for curtailing fungal virulence and/or inhibiting the development of resistance to anti-fungal drugs.

We also identified a number of proteins involved in protein synthesis and glycolysis which are typically conserved among eukaryotes. A vaccination strategy targeting proteins conserved among eukaryotes [including those involved in protein synthesis, glycogenic pathways, and resistance to environmental stress] is traditionally considered an unwise strategy due to the potential for inducing autoimmune responses to similar host antigens. However, mice treated with recombinant enolase, also referred to as phosphopyruvate hydratase, conferred some protection against an experimental systemic challenge with C. albicans [67]. Thus, experimental vaccination studies utilizing heat shock proteins or enolase to stimulate immunity suggest that vaccine strategies targeting conserved eukaryotic proteins are possible. Interestingly, enolase was identified in previous immunoblot studies using serum from protectively immunized mice [35].

In conclusion, our studies support using a combined immunological and proteomic approach to screen complex mixtures of cryptococcal proteins for those proteins that elicit C. neoformans-specific antibody and Th1-type cytokine recall responses. We also extended our previous analysis by identifying C. neoformans protein fractions that induce antigen specific antibody and Th1-type cytokine recall responses and have the potential for prolonging survival in experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis. Additionally, these studies support the possibility of including antigens conserved among eukaryotes in sub-unit vaccines to target fungal pathogens. Additional studies are required to evaluate the efficacy of individual proteins within the fractions to extend protection against experimental C. neoformans infection in mice. Nevertheless, our analysis provides additional candidates that may be used for the development of novel immune-based approaches to treat and/or prevent cryptococcosis particularly in immunocompromised patients. Studies have shown that protection against pulmonary cryptococcosis can be generated in immunosuppressed hosts [70]. Thus, vaccine formulations incorporating the right combination of antigens and adjuvant or recombinant cytokines have the potential for inducing protective immunity against C. neoformans infections in immunedeficient patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the Army Research Office of the Department of Defense under Contract No. W911NF-11-1-0136 and grants RO1 AI071752 and R21 AI083718 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded to Dr. Wormley, and the San Antonio Vaccine Development Center. Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted in the UTHSCSA Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory; we are grateful for the invaluable technical assistance of Kevin Hakala and Sam Pardo for these analyses.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Defense or NIAID of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Chuck SL, Sande MA. Infections with Cryptococcus neoformans in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:794–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909213211205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dismukes WE. Cryptococcal meningitis in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:624–628. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eng RH, Bishburg E, Smith SM, Kapila R. Cryptococcal infections in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1986;81:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gal AA, Koss MN, Hawkins J, Evans S, Einstein H. The pathology of pulmonary cryptococcal infections in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovacs JA, Kovacs AA, Polis M, Wright WC, et al. Cryptococcosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:533–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diamond RD, Bennett JE. Prognostic factors in cryptococcal meningitis. A study in 111 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:176–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-2-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duperval R, Hermans PE, Brewer NS, Roberts GD. Cryptococcosis, with emphasis on the significance of isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans from the respiratory tract. Chest. 1977;72:13–19. doi: 10.1378/chest.72.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein E, Rambo ON. Cryptococcal infection following steroid therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1962;56:114–120. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-56-1-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins VP, Gellhorn A, Trimble JR. The coincidence of cryptococcosis and disease of the reticulo-endothelial and lymphatic systems. Cancer. 1951;4:883–889. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195107)4:4<883::aid-cncr2820040426>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gendel BR, Ende M, Norman SL. Cryptococcosis; a review with special reference to apparent association with Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Med. 1950;9:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(50)90430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keye JD, Jr, Magee WE. Fungal diseases in a general hospital; a study of 88 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1956;26:1235–1253. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/26.11.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis JL, Rabinovich S. The wide spectrum of cryptococcal infections. Am J Med. 1972;53:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in organ transplant recipients: variables influencing clinical characteristics and outcome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:375–381. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, et al. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vibhagool A, Sungkanuparph S, Mootsikapun P, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis for cryptococcal meningitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: a prospective, multicenter, randomized study. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1329–1331. doi: 10.1086/374849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozzette SA, Larsen RA, Chiu J, Leal MA, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of maintenance therapy with fluconazole after treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. California Collaborative Treatment Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:580–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102283240902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aberg Judith A, Price Richard W, Heeren Dorie M, Bredt B. A Pilot Study of the Discontinuation of Antifungal Therapy for Disseminated Cryptococcal Disease in Patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome following Immunologic Response to Antiretroviral Therapy. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;185:1179–1182. doi: 10.1086/339680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dromer F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Fontanet A, Ronin O, et al. Epidemiology of HIV-associated cryptococcosis in France (1985–2001): comparison of the pre- and post-HAART eras. AIDS. 2004;18:555–562. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh N, Perfect JR. Immune reconstitution syndrome associated with opportunistic mycoses. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:395–401. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguirre K, Havell EA, Gibson GW, Johnson LL. Role of tumor necrosis factor and gamma interferon in acquired resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans in the central nervous system of mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1725–1731. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1725-1731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins HL, Bancroft GJ. Cytokine enhancement of complement-dependent phagocytosis by macrophages: synergy of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1447–1454. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flesch IE, Schwamberger G, Kaufmann SH. Fungicidal activity of IFN-gamma-activated macrophages. Extracellular killing of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1989;142:3219–3224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF. Cells and cytokines in pulmonary cryptococcosis. Res Immunol. 1998;149:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80762-1. discussion 512–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levitz SM. Activation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by interleukin-2 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to inhibit Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3393–3397. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3393-3397.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitz SM, DiBenedetto DJ. Differential stimulation of murine resident peritoneal cells by selectively opsonized encapsulated and acapsular Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2544–2551. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2544-2551.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mody CH, Tyler CL, Sitrin RG, Jackson C, Toews GB. Interferon-gamma activates rat alveolar macrophages for anticryptococcal activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;5:19–26. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/5.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClelland EE, Nicola AM, Prados-Rosales R, Casadevall A. Ab binding alters gene expression in Cryptococcus neoformans and directly modulates fungal metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1355–1361. doi: 10.1172/JCI38322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brena S, Cabezas-Olcoz J, Moragues MD, Fernandez de Larrinoa I, et al. Fungicidal monoclonal antibody C7 interferes with iron acquisition in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3156–3163. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00892-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Antibody-mediated protection through cross-reactivity introduces a fungal heresy into immunological dogma. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5074–5078. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez LR, Casadevall A. Specific antibody can prevent fungal biofilm formation and this effect correlates with protective efficacy. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6350–6362. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6350-6362.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramaniam KS, Datta K, Quintero E, Manix C, et al. The absence of serum IgM enhances the susceptibility of mice to pulmonary challenge with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2010;184:5755–5767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biondo C, Messina L, Bombaci M, Mancuso G, et al. Characterization of two novel cryptococcal mannoproteins recognized by immune sera. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7348–7355. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7348-7355.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kakeya H, Udono H, Maesaki S, Sasaki E, et al. Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) as a major target of the antibody response in patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:485–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00821.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakeya H, Udono H, Ikuno N, Yamamoto Y, et al. A 77-kilodalton protein of Cryptococcus neoformans, a member of the heat shock protein 70 family, is a major antigen detected in the sera of mice with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1653–1658. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1653-1658.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young M, Macias S, Thomas D, Wormley FL., Jr A proteomic-based approach for the identification of immunodominant Cryptococcus neoformans proteins. Proteomics. 2009;9:2578–2588. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wozniak KL, Hardison SE, Kolls JK, Wormley FL. Role of IL-17A on resolution of pulmonary C. neoformans infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wormley FL, Jr, Perfect JR, Steele C, Cox GM. Protection against cryptococcosis by using a murine gamma interferon-producing Cryptococcus neoformans strain. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1453–1462. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00274-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell TG, Perfect JR. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS--100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:515–548. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iseki M, Anzo M, Yamashita N, Matsuo N. Hyper-IgM immunodeficiency with disseminated cryptococcosis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:780–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Neto RJ, Guimaraes MC, Moya MJ, Oliveira FR, et al. Hypogammaglobulinemia as risk factor for Cryptococcus neoformans infection: report of 2 cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee J, Feldmesser M, Scharff MD, Casadevall A. Monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan enhance fluconazole efficacy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1398–1405. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukherjee J, Zuckier LS, Scharff MD, Casadevall A. Therapeutic efficacy of monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan alone and in combination with amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:580–587. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dromer F, Charreire J. Improved amphotericin B activity by a monoclonal anti-Cryptococcus neoformans antibody: study during murine cryptococcosis and mechanisms of action. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1114–1120. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldmesser M, Mukherjee J, Casadevall A. Combination of 5-flucytosine and capsule-binding monoclonal antibody in the treatment of murine Cryptococcus neoformans infections and in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:617–622. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dromer F, Charreire J, Contrepois A, Carbon C, Yeni P. Protection of mice against experimental cryptococcosis by anti-Cryptococcus neoformans monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1987;55:749–752. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.749-752.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldman DL, Lee SC, Casadevall A. Tissue localization of Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan in the presence and absence of specific antibody. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3448–3453. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3448-3453.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukherjee J, Scharff MD, Casadevall A. Protective murine monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4534–4541. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4534-4541.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukherjee S, Lee S, Mukherjee J, Scharff MD, Casadevall A. Monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide modify the course of intravenous infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1079–1088. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1079-1088.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinez LR, Christaki E, Casadevall A. Specific antibody to Cryptococcus neoformans glucurunoxylomannan antagonizes antifungal drug action against cryptococcal biofilms in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:261–266. doi: 10.1086/504722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez LR, Casadevall A. Specific antibody can prevent fungal biofilm formation and this effect correlates with protective efficacy. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6350–6362. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6350-6362.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Antibody-mediated protection through cross-reactivity introduces a fungal heresy into immunological dogma. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5074–5078. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Wang F, Tompkins KC, McNamara A, et al. Robust Th1 and Th17 immunity supports pulmonary clearance but cannot prevent systemic dissemination of highly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans H99. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2489–2500. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muller U, Stenzel W, Kohler G, Werner C, et al. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2007;179:5367–5377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardison SE, Wozniak KL, Kolls JK, Wormley FL., Jr Interleukin-17 is not required for classical macrophage activation in a pulmonary mouse model of Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78:5341–5351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wozniak KL, Ravi S, Macias S, Young ML, et al. Insights into the mechanisms of protective immunity against Cryptococcus neoformans infection using a mouse model of pulmonary cryptococcosis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaffin WL, Lopez-Ribot JL, Casanova M, Gozalbo D, Martinez JP. Cell wall and secreted proteins of Candida albicans: identification, function, and expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:130–180. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.130-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez-Lopez R, Nombela C, Diez-Orejas R, Monteoliva L, Gil C. Immunoproteomic analysis of the protective response obtained from vaccination with Candida albicans ecm33 cell wall mutant in mice. Proteomics. 2008;8:2651–2664. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Groot PW, Ram AF, Klis FM. Features and functions of covalently linked proteins in fungal cell walls. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:657–675. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robbins N, Uppuluri P, Nett J, Rajendran R, et al. Hsp90 governs dispersion and drug resistance of fungal biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002257. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cowen LE. Hsp90 orchestrates stress response signaling governing fungal drug resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000471. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh SD, Robbins N, Zaas AK, Schell WA, et al. Hsp90 governs echinocandin resistance in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans via calcineurin. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000532. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cowen LE, Lindquist S. Hsp90 potentiates the rapid evolution of new traits: drug resistance in diverse fungi. Science. 2005;309:2185–2189. doi: 10.1126/science.1118370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deepe GS, Jr, Gibbons RS. Cellular molecular regulation of vaccination with heat shock protein 60 from Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3759–3767. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3759-3767.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gomez FJ, Allendoerfer R, Deepe GS., Jr Vaccination with recombinant heat shock protein 60 from Histoplasma capsulatum protects mice against pulmonary histoplasmosis. Infection and immunity. 1995;63:2587–2595. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2587-2595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Bastos Ascenco Soares R, Gomez FJ, de Almeida Soares CM, Deepe GS., Jr Vaccination with heat shock protein 60 induces a protective immune response against experimental Paracoccidioides brasiliensis pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4214–4221. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00753-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li W, Hu X, Zhang X, Ge Y, et al. Immunisation with the glycolytic enzyme enolase confers effective protection against Candida albicans infection in mice. Vaccine. 2011;29:5526–5533. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raska M, Belakova J, Horynova M, Krupka M, et al. Systemic and mucosal immunization with Candida albicans hsp90 elicits hsp90-specific humoral response in vaginal mucosa which is further enhanced during experimental vaginal candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2008;46:411–420. doi: 10.1080/13693780701883508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li K, Yu JJ, Hung CY, Lehmann PF, Cole GT. Recombinant urease and urease DNA of Coccidioides immitis elicit an immunoprotective response against coccidioidomycosis in mice. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:2878–2887. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2878-2887.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wozniak KL, Young ML, Wormley FL., Jr Protective immunity against experimental pulmonary cryptococcosis in T cell-depleted mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:717–723. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00036-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.