Abstract

Background

Viral infections are the most frequent cause of asthma exacerbations and are linked to increased airway reactivity (AR) and inflammation. Mice infected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) during ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation (OVA/RSV) had increased AR compared to OVA or RSV mice alone. Further, IL-17A was only increased in OVA/RSV mice.

Objective

To determine if IL-17A increases AR and inflammation in the OVA/RSV model.

Methods

Wild-type BALB/c and IL-17A KO mice underwent mock, RSV, OVA, or OVA/RSV protocols. Lungs, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, and/or mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) were harvested post infection. Cytokine expression was determined by flow cytometry and ELISA in the lungs or BAL fluid. MLNs were restimulated with either OVA (323–229) peptide or RSV M2 (127–135) peptide and IL-17A protein expression was analyzed. AR was determined by methacholine challenge.

Results

RSV increased IL-17A protein expression by OVA-specific T cells 6 days post infection. OVA/RSV mice had decreased IFN-α and IFN-β protein expression compared to RSV mice. OVA/RSV mice had increased IL-23 mRNA expression in lung homogenates compared to mock, OVA, or RSV mice. Unexpectedly, IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had increased AR compared to WT OVA/RSV mice. Further, IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had increased eosinophils, lymphocytes, and IL-13 protein expression in BAL fluid compared to WT OVA/RSV mice.

Conclusions

IL-17A negatively regulated AR and airway inflammation in OVA/RSV mice. This finding is important because IL-17A has been identified as a potential therapeutic target in asthma, and inhibiting IL-17A in the setting of virally induced asthma exacerbations may have adverse consequences.

Keywords: IL-17A, airway reactivity, CD4+ T cells, allergic inflammation, RSV

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is characterized by increased lung inflammation, airway reactivity (AR) and mucus production. Viral infections trigger 80–85% of asthma exacerbations in children1 and 44% in adults.2 Most of these viral-induced asthma events occur in patients with allergic airway inflammation.3 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is associated with many wheezing episodes and asthma exacerbations.4 However, the exact mechanisms by which viral infections cause asthma exacerbations remain unknown.

To determine the immunological mechanisms associated with viral-induced asthma exacerbations, we previously developed a mouse model of RSV strain A2 infection during ongoing ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation (OVA/RSV) in BALB/c mice.5 Eight days after infection, OVA/RSV mice had the same AR as OVA mice, and both groups were significantly increased compared to non-allergic, uninfected mice (mock) or RSV infected mice. However, 15 days after RSV challenge, OVA/RSV mice had significantly increased AR compared to OVA mice, in which AR had declined over time. This model closely mimics the heightened and prolonged AR that occurs with virally-induced asthma exacerbations in people. Interestingly, RSV strain A2 infection without allergic airway inflammation did not cause increased AR over mock mice at any time point.5

Interleukin (IL)-13, a Th2 cytokine, is a central mediator of AR and airway mucus production in allergic airway models. Lung IL-13 protein expression was significantly increased in OVA mice compared to mock mice,6;7 but lung IL-13 protein expression was significantly reduced in OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA mice.6;7 These findings suggest IL-13 was not responsible for increased AR in OVA/RSV mice. However, OVA/RSV mice had a significant increase in lung IL-17A protein expression,7 a cytokine associated with severe asthma.8;9 Based on these findings, we hypothesized that IL-17A mediates increased AR and inflammation that occurs in OVA/RSV mice compared to WT mice.

IL-17A is produced primarily by Th17 cells, and IL-17A signals through a heterodimeric receptor composed of IL-17RA and IL-17RC subunits.10 IL-17A is associated with autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases, as well as protection against extracellular pathogens.10 IL-17A protein expression was also increased in BAL fluid and bronchial biopsy tissue of patients with moderate to severe asthma.8;9

Initially, IL-17A was thought to be essential for allergic airway inflammation because mice deficient in IL-17RA failed to develop OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation.11 However, the lack of allergic airway inflammation in IL-17RA mice was later attributed to the inability of these mice to respond to IL-17E, also known as IL-25, which also signals through IL-17RA. IL-25 was required for allergic airway inflammation and increased IL-13 protein expression, eosinophil recruitment, and AR.12 Barlow and colleagues showed that IL-25 increased IL-13 which decreased IL-17A protein expression.13 Further, IL-17A protected against increased AR and allergic airway inflammation.13 These studies show a role for IL-17A in regulating airway inflammation, but the role of IL-17A in viral-induced AR and airway inflammation in the setting of underlying allergic inflammation has not been elucidated. Therefore, our objective was to determine the role of IL-17A in airway inflammation and AR in a clinically relevant model of asthma exacerbation in which viral infection occurs during ongoing allergic airway inflammation. This is vital since therapeutics which inhibit IL-17A are currently in clinical trials for asthma could have unintended effects on allergic airway inflammation.14

METHODS

Mice

Pathogen-free eight to ten-week old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. IL-17A knockout (KO) mice on a BALB/c background were provided by Jay Kolls (University of Pittsburgh).

Allergic sensitization/challenge and RSV infection of mice

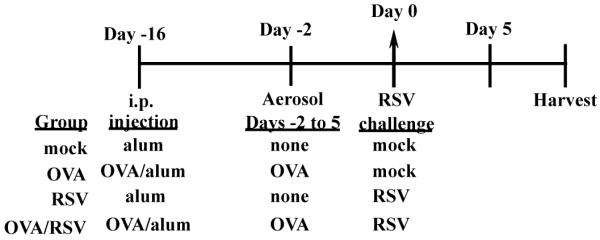

Mice were categorized into 4 groups: mock, OVA, RSV, and OVA/RSV. The protocol for OVA sensitization/challenge and RSV infection is shown in Figure 1 and has been previously described.5;6 RSV was provided by R. Chanock (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and RSV stock was generated as previously described.15

Figure 1.

Timeline of experimental protocol for OVA/RSV mice. OVA and OVA/RSV mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of OVA complexed with Al(OH)3 (alum) on day −16. Mock and RSV mice were i.p. injected with alum on day −16. On days −2 through 5 OVA and OVA/RSV mice were challenged for with 1% OVA (in PBS). On day 0, RSV and OVA/RSV mice were infected with RSV strain A2, and mock and OVA mice were challenged with uninfected cell culture supernatants. Harvests occurred at various time points post mock or RSV challenge.

Restimulation of mediastinal lymph nodes

Mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) were removed and homogenized from OVA, RSV, or OVA/RSV mice on day 6. MLN cells were stimulated with no peptide (vehicle), OVA peptide 323–339 (1μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich), RSV M2 (127–135) peptide (10−7M) (Biosynthesis, Inc.) or influenza peptide (FLU 147–155) (10−7M) as a non-specific negative control (Biosynthesis, Inc.). Cell culture supernatants were collected 24 hours after stimulation.

Cytokine measurements

Cytokine levels were measured by ELISA (R & D Systems). Values below the limit of detection were assigned half the value of the lowest detectable standard.

Airway reactivity measurements

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, placed in (85 mg/kg) and a tracheostomy tube was placed and the internal jugular vein was cannulated. Mice were then placed in a plethysmography chamber and mechanically ventilated. Lung resistance was measured following administration of intravenous acetyl-ß-methacholine (0–3700μg/kg body weight) (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described.5;6

Statistical analyses

Data is presented as mean ± SEM with data shown from 1 experiment. Each experiment was repeated three times to ensure the reproducibility of the data. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey posthoc test or a 2-tailed t-test with values being considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

CD4 T cells express IL-17A protein in OVA/RSV mice

We previously found that lung IL-17A protein expression in lung homogenates peaked at day 6 and was significantly increased in OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA or RSV mice.7 Many cell types express IL-17A including γδ T cells, neutrophils, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.16–18 Therefore, we wanted to determine the specific cell type responsible for IL-17A protein expression in OVA/RSV mice. We measured IL-17A protein expression by flow cytometry from the lungs of OVA/RSV mice on day 6. IL-17A expression was significantly increased in CD3+ CD4+ cells compared to CD3+CD8+, γδ TCR+, Gr-1+, and CD11c+ cells (Supplemental Figure 1A–F). These data show that CD3+ CD4+ T cells primarily produce IL-17A in the OVA/RSV mice.

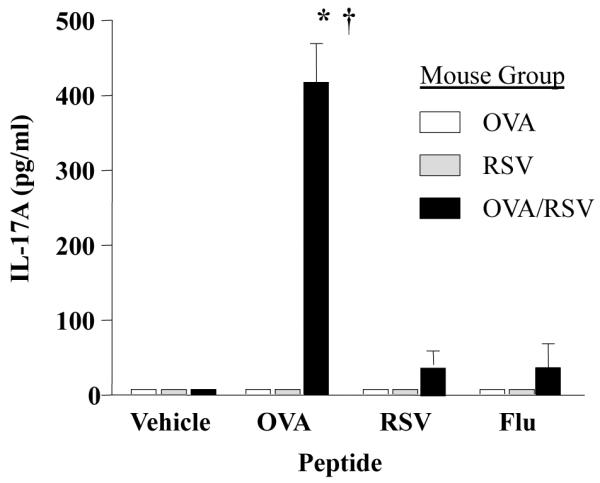

OVA peptide restimulation increases IL-17A protein expression in cells from MLNs

IL-17A protein expression was maximally increased in T cells from OVA/RSV mice, but we questioned whether OVA-specific or RSV-specific T cells were the source of IL-17A protein expression. OVA-specific T cells are present in the lung at the time of RSV infection, therefore we hypothesized that RSV infection increased the number of OVA-specific T cells expression IL-17A. We harvested MLNs from OVA, RSV, or OVA/RSV mice 6 days post infection and restimulated the cells with media alone (vehicle), OVA (323–339) peptide, RSV M2 (127–135) peptide or a non-specific control influenza peptide (Flu 147–155). IL-17A protein expression was examined in cell culture supernatants 24 hours after stimulation. Only OVA/RSV MLN cells incubated with OVA peptide had significantly increased IL-17A protein expression compared to vehicle, RSV peptide, or Flu peptide (Figure 2). Mice in the OVA or RSV groups had no detectable IL-17A protein expression with any peptide treatment. These data show that RSV infection increases IL-17A protein expression by OVA-specific T cells.

Figure 2.

IL-17 protein expression is increased in MLN cells from OVA/RSV mice restimulated with OVA peptide. MLN single cell suspensions from OVA, RSV, or OVA/RSV mice were restimulated with media alone (vehicle), OVA (323–339) peptide, RSV M2 (127–135) peptide or Flu (147–155) peptide for 24 hours in vitro. IL-17A protein expression in supernatants was examined by ELISA. n= 4–5, ANOVA, * p<0.05 compared to no peptide (vehicle), † p<0.05 compared to OVA or RSV mouse groups.

IL-23 mRNA expression is increased by RSV infection during ongoing allergic airway inflammation

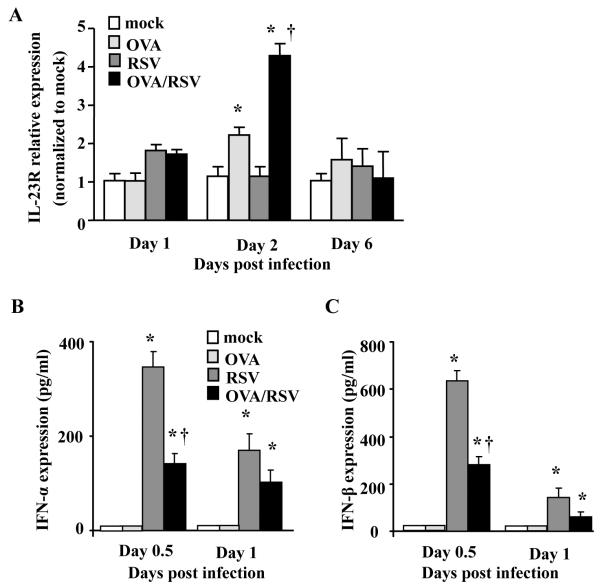

We next wanted to determine the mechanism for increased IL-17A in OVA/RSV mice. IL-23 is a cytokine required for Th17 cell sustainability and production of IL-17A,19–21 and therefore we examined mRNA relative expression of IL-23 on days 1, 2, and 6 post infection in the mock, RSV, OVA, or OVA/RSV mice. We hypothesized that IL-23 is increased with RSV infection during ongoing allergic airway inflammation, supporting conditions for significantly increased IL-17A protein expression in OVA/RSV mice. IL-23 relative mRNA expression was significantly increased on day 2 in OVA and OVA/RSV mice compared to mock and RSV mice (Figure 3A). IL-23 relative expression was significantly increased in OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA mice. RSV mice had no increase in IL-23 relative expression compared to mock. These data suggest that increased IL-23 expression in OVA/RSV mice led to increased IL-17A protein expression.

Figure 3.

OVA/RSV mice have increased IL-23 mRNA expression and decreased type I IFN protein expression. (A) IL-23 mRNA expression was determined from whole lung homogenates by real-time PCR on days 1, 2, and 6. Samples were normalized to GAPDH and then mock animals. (B–C) IFN-α and IFN-β protein expression was determined from whole lung homogenates by ELISA on days 0.5 and 1. n=5–6, ANOVA, *p<0.05 compared to mock mice, † p<0.05 compared to OVA mice (A) or RSV mice (B–C).

Pre-existing allergic airway inflammation decreases type I IFN response with RSV infection

Type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β, are significantly increased with RSV infection,22 and negatively regulate IL-17A production.23 As lung IL-17A expression is increased in OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA mice, we hypothesized that OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation decreases type I IFN protein expression resulting from RSV infection. Lungs were harvested on days 0.5 day (12 hours) and day 1 and analyzed for IFN-α and IFN-β protein expression. RSV infected mice had significant increases in IFN-α and IFN-β protein expression that was maximal at 0.5 days post infection compared to mock (Figure 4B and C). However, OVA/RSV mice had a significant decrease in IFN-α and IFN-β protein expression at 0.5 days post infection compared to RSV mice (Figure 4B and C). These data show that pre-existing allergic airway inflammation diminished type I IFN immune response to viral infection.

Figure 4.

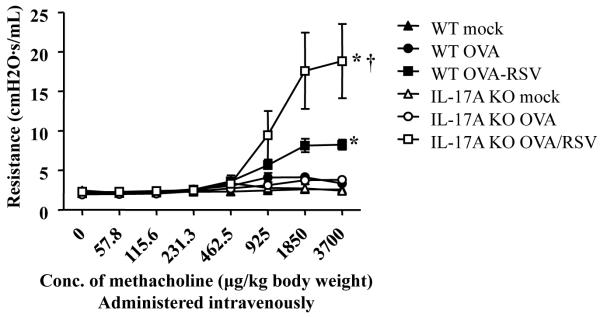

IL-17A negatively regulates AR in OVA/RSV mice. WT and IL-17A KO mice were RSV infected during ongoing allergic airway inflammation. On day 15, AR was measured by detecting changes in airway resistance in response to increasing concentrations of methacholine. n=7–15 mice, ANOVA, *p<0.05 compared to WT mock mice, † p<0.05 compared to WT OVA/RSV mice.

IL-17A inhibits AR and airway inflammation in OVA/RSV mice

IL-17A was significantly increased only in the lungs of OVA/RSV mice,7 and OVA/RSV mice had an increase in AR.5;6 In addition, IL-17A has been associated with severe asthma in humans.8;9 Therefore, we hypothesized that IL-17A was responsible for the increased AR in OVA/RSV mice 15 days after infection and 9 days after the last exposure to aerosolized OVA. This is a time point at which the AR in the OVA group was significantly diminished.5 We measured AR in mock, OVA, and OVA/RSV groups in WT and IL-17A KO mice. To our surprise, IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had significantly increased AR compared to WT OVA/RSV mice (Figure 4). In a separate experiment we analyzed AR in WT RSV and IL-17A KO RSV mice. The magnitude of AR was lower in RSV mice compared to OVA/RSV mice, but IL-17A KO RSV mice had a significant increase in AR compared to WT RSV mice (Supplemental Figure 2). These data are in contrast to our hypothesis and suggest that IL-17A plays a regulatory role by inhibiting AR in the OVA/RSV model.

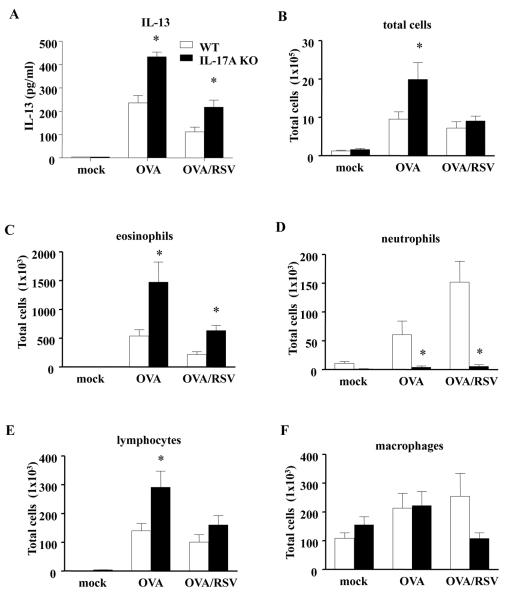

IL-17A inhibits IL-13 and infiltration of eosinophils in OVA/RSV mice

Since IL-17A negatively regulated AR in OVA/RSV mice, we examined IL-13 protein in BAL fluid on day 2, the point of maximal IL-13 protein expression in OVA/RSV mice.7 IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had significantly increased IL-13 protein expression compared to WT OVA/RSV mice (Figure 5A). IL-17A KO OVA mice also had significantly increased IL-13 compared to WT OVA mice (Figure 5A). We also examined the presence of inflammatory cells (Figure 5B–F) in BAL fluid on day 2. IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had significantly increased eosinophils compared to WT OVA/RSV mice (Figure 5C). IL-17A KO OVA mice had significantly increased total inflammatory cells, eosinophils and lymphocytes compared to WT OVA mice (Figure 5B, C, and E). As IL-17A has been shown to be important in lung neutrophil recruitment, we hypothesized that IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice have decreased airway neutrophils compared to WT OVA/RSV mice. IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had significantly decreased neutrophil infiltration compared to WT OVA/RSV mice (Figure 5D). Taken together these data suggest IL-17A inhibits allergic airway inflammation by negatively regulating IL-13 protein expression and eosinophil and lymphocyte recruitment with RSV infection during ongoing allergic airway inflammation.

Figure 5.

IL-17A negatively regulates allergic airway inflammation in OVA/RSV mice. WT and IL-17A KO mice were RSV infected during ongoing allergic airway inflammation. BAL fluid was harvested on day 2. (A) IL-13 protein expression from BAL fluid as measured by ELISA. (B–F) Infiltration of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid. n=5 mice, ANOVA, *p<0.05 compared to WT mice for respective condition.

DISCUSSION

Viral infections are a leading cause of asthma exacerbations in children and adults,1;2 and many of these patients have allergic airway inflammation.3 We have previously shown IL-17A protein expression was increased in OVA/RSV mice.7 In this study, we showed that IL-17A is produced from OVA-specific CD3+CD4+ cells and not other cells known to produce IL-17A. We also showed that OVA/RSV mice had increased IL-23 relative expression, but decreased type I IFN immune responses in lung homogenates compared to OVA or RSV mice. Surprisingly, we found that IL-17A protected against AR and airway inflammation in the setting of viral infection during allergic airway inflammation, as IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had increased AR, IL-13 protein expression, and eosinophil and lymphocytes infiltration compared to WT OVA/RSV mice.

RSV infections typically generate a Th1-mediated response with increased protein expression of IFN-γ, and allergic airway inflammation generates a Th2-mediated response with increased protein expression of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. However, RSV infection during ongoing allergic airway inflammation increased IL-17A protein expression and decreased IFN-γ and IL-13 protein expression.7 In our experiments, OVA-specific T cells were the cellular source of IL-17A, and there are several possible mechanisms by which RSV could increase OVA-specific CD4+ T cell generation of IL-17A. First, RSV infection increased lung IL-6 expression,6 a cytokine that drives Th17 differentiation in mice.24;25 In addition, we found that RSV infection in the setting of allergic airway inflammation increased lung IL-23 mRNA expression, a cytokine important in the sustainability of the Th17 phenotype,24 while RSV infection by itself did not result in increased lung IL-23 expression. Therefore, increased IL-6 and IL-23 created the cytokine milieu that enhances Th17 cell differentiation.

We also found that allergic airway inflammation decreased type I IFN production after RSV infection in the OVA/RSV mice compared to RSV infected mice alone. Type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β, are known to negatively regulate IL-17A protein expression by increasing IL-27 protein expression from dendritic cells.23;26 Type I IFNs are also known to drive IFN-γ expression from Th1 cells. As allergic airway inflammation decreased RSV-induced lung type I IFN expression this might explain the decreased lung IFN-γ expression in OVA/RSV mice compared to RSV mice. As IFN-γ is a negative regulator of IL-17A expression, the decreased IFN-γ in the OVA/RSV group might explain the increased lung IL-17A expression in OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA mice. Decreased expression of viral-induced type I IFNs and IFN-γ have been associated with asthma. RV-infected primary bronchial epithelial cells obtained from patients with asthma had decreased type I IFN response compared to rhinovirus-infected BECs from normal patients.27 Further, IFN-γ was decreased in mononuclear cells of adult asthmatic patients infected with RV.28 Together these data suggest that allergic airway inflammation decreases the IFN response to viral infections, consequently leading to increased IL-17A protein expression.

Other cells types, such as CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, and neutrophils secrete IL-17A,16–18 but we did not find IL-17A protein expression in these cells 6 days post infection. These cells may secrete IL-17A very shortly after RSV infection, but IL-17A was undetectable by ELISA in whole lung homogenates when examined at various time points post RSV infection and so this is unlikely.7

IL-17A has been reported to be increased in BAL fluid and bronchial biopsy of patients with severe asthma.8;9 IL-17A protein expression, and not IL-13, was significantly increased in the whole lung homogenates of OVA/RSV mice compared to OVA mice alone.7 Therefore, we hypothesized that IL-17A increased AR in the OVA/RSV mice. In contrast to our hypothesis IL-17A OVA/RSV KO mice had increased AR compared to WT OVA/RSV KO mice alone. No significant changes in AR were seen in the IL-17A KO OVA mice compared to WT OVA mice, 9 days other the last OVA aerosol challenge in OVA experimental protocol. AR was increased in IL-17A KO RSV mice compared to WT RSV mice, but the magnitude in maximal AR was much smaller in the RSV group compared to OVA/RSV group for both WT and IL-17A KO mice. Th17 cells secrete other cytokines including IL-17F and IL-22. Therefore, we examined IL-17F and IL-22 protein expression in whole lung homogenates of WT and IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice. No difference in lung IL-17F or IL-22 protein expression was detected in IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice compared to WT OVA/RSV mice (data not shown) suggesting the increased AR in the IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice was independent of IL-17F and IL-22 protein expression.

The role of IL-17A in mouse models of AR is conflicting in the literature. Neutralization of IL-17A prior to house dust mite exposure decreased AR and eosinophil infiltration into the airway,29;30 and IL-17A was enhanced by complement 3a signaling in this model.29 Further, RSV A2 infection in mice deficient in complement 3a receptor or tachykinin receptor resulted in a significant decrease in IL-17A protein expression and AR.31 IL-17A also increased airway smooth muscle contraction.32 These results suggest IL-17A may be responsible for increases in AR in allergen-challenge and viral models. However, Schnyder-Candrian and colleagues reported that intranasally instilling recombinant IL-17A into airways of mice concurrent with OVA challenge in OVA allergic airway model significantly decreased enhance respiratory pause (Penh) in response to methacholine, eosinophil infiltration, and the chemokines CCL5, CCL11, and CCL17.11 Further, Barlowe and colleagues found that neutralizing IL-17A increased airway eosinophilia and AR during a model of allergic airway inflammation.13 We extend these findings by showing that IL-17A had a protective role on AR in a model of viral infection during allergic airway inflammation. Our findings are very important for viral-induced asthma events.

IL-17A KO OVA/RSV mice had increased IL-13 protein expression, eosinophils, and lymphocytes in BAL fluid compared to WT OVA/RSV mice. These increases provide a mechanism for increased AR in IL17A KO OVA/RSV mice compared to WT mice. In addition, IL-13 suppressed IL-17A both in vitro and in vivo.13;33;34 However, in this study our data shows that IL-17A suppresses IL-13 protein expression and eosinophil infiltration to the lung. This finding is important because clinical trials are currently planned to target IL-17A as a therapy for patients with inadequately controlled or steroid resistant asthma.14 Combined, these results suggest that neutralizing IL-17A as a potential therapy for viral-induced asthma exacerbations may have unintended consequences of increased AR and airway inflammation. Therefore, further studies to understand the role of IL-17A in increased allergic airway inflammation and AR are vital for determining the impact of inhibiting or neutralizing IL-17A as a therapeutic for patients with asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank William Lawson for use of his real-time PCR machine supported in part by a grant from National Institute of Health (1UL 1RR024975).

Funding: National Institute of Health R01 HL 090664, R01 AI 070672, R01 AI 059108, GM 015431, R21 HL106446, U19AI095227, K12HD043483-08 and Veteran Affairs (1I01BX000624).

Abbreviations

- AR

airway reactivity

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- IL

interleukin

- I.P.

intraperitoneal

- KO

knockout

- MLNs

mediastinal lymph nodes

- OVA

ovalbumin

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: The authors have no competing interests with this study.

Ethics: In caring for the animals, investigators adhered to the revised 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, et al. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9–11 year old children. BMJ. 1995;310:1225–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. BMJ. 1993;307:982–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green RM, Custovic A, Sanderson G, et al. Synergism between allergens and viruses and risk of hospital admission with asthma: case-control study. BMJ. 2002;324:763. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7340.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, et al. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2005;171:137–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-730OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peebles RS, Jr., Sheller JR, Johnson JE, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection prolongs methacholine-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. J.Med.Virol. 1999;57:186–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199902)57:2<186::aid-jmv17>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peebles RS, Jr., Sheller JR, Collins RD, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection does not increase allergen-induced type 2 cytokine production, yet increases airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J.Med.Virol. 2001;63:178–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto K, Graham BS, Ho SB, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in allergic lung inflammation increases Muc5ac and gob-5. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2004;170:306–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-030OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakir J, Shannon J, Molet S, et al. Airway remodeling-associated mediators in moderate to severe asthma: effect of steroids on TGF-beta, IL-11, IL-17, and type I and type III collagen expression. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2003;111:1293–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molet S, Hamid Q, Davoine F, et al. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2001;108:430–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaffen SL. Recent advances in the IL-17 cytokine family. Curr.Opin.Immunol. 2011;23:613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnyder-Candrian S, Togbe D, Couillin I, et al. Interleukin-17 is a negative regulator of established allergic asthma. J.Exp.Med. 2006;203:2715–25. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballantyne SJ, Barlow JL, Jolin HE, et al. Blocking IL-25 prevents airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic asthma. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2007;120:1324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow JL, Flynn RJ, Ballantyne SJ, et al. Reciprocal expression of IL-25 and IL-17A is important for allergic airways hyperreactivity. Clin.Exp.Allergy. 2011;41:1447–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed July 6, 2012]; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01199289?term=amg+827+asthma&rank=1. 4-5-0012. Search terms AMG 827 and AIN 457.

- 15.Graham BS, Perkins MD, Wright PF, et al. Primary respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J.Med.Virol. 1988;26:153–62. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eustace A, Smyth LJ, Mitchell L, et al. Identification of cells expressing IL-17A and IL-17F in the lungs of patients with COPD. Chest. 2011;139:1089–100. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamada H, Garcia-Hernandez ML, Reome JB, et al. Tc17, a unique subset of CD8 T cells that can protect against lethal influenza challenge. J.Immunol. 2009;182:3469–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien RL, Roark CL, Born WK. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Eur.J.Immunol. 2009;39:662–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat.Immunol. 2005;6:1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Langrish CL, McKenzie B, et al. Anti-IL-23 therapy inhibits multiple inflammatory pathways and ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J.Clin.Invest. 2006;116:1317–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoeve MA, Savage ND, de Boer T, et al. Divergent effects of IL-12 and IL-23 on the production of IL-17 by human T cells. Eur.J.Immunol. 2006;36:661–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jewell NA, Vaghefi N, Mertz SE, et al. Differential type I interferon induction by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza a virus in vivo. J.Virol. 2007;81:9790–800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00530-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J.Clin.Invest. 2008;118:1680–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI33342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirahara K, Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, et al. Signal transduction pathways and transcriptional regulation in Th17 cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:425–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat.Immunol. 2007;8:967–74. doi: 10.1038/ni1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinohara ML, Kim JH, Garcia VA, et al. Engagement of the type I interferon receptor on dendritic cells inhibits T helper 17 cell development: role of intracellular osteopontin. Immunity. 2008;29:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wark PA, Johnston SL, Bucchieri F, et al. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J.Exp.Med. 2005;201:937–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks GD, Buchta KA, Swenson CA, et al. Rhinovirus-induced interferon-gamma and airway responsiveness in asthma. Am.J.Respir.Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1091–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-737OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lajoie S, Lewkowich IP, Suzuki Y, et al. Complement-mediated regulation of the IL-17A axis is a central genetic determinant of the severity of experimental allergic asthma. Nat.Immunol. 2010;11:928–35. doi: 10.1038/ni.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee S, Lindell DM, Berlin AA, et al. IL-17-Induced Pulmonary Pathogenesis during Respiratory Viral Infection and Exacerbation of Allergic Disease. Am.J.Pathol. 2011;179:248–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bera MM, Lu B, Martin TR, et al. Th17 cytokines are critical for respiratory syncytial virus-associated airway hyperreponsiveness through regulation by complement C3a and tachykinins. J.Immunol. 2011;187:4245–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kudo M, Melton AC, Chen C, et al. IL-17A produced by alphabeta T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat.Med. 2012;18:547–54. doi: 10.1038/nm.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newcomb DC, Zhou W, Moore ML, et al. A functional IL-13 receptor is expressed on polarized murine CD4+ Th17 cells and IL-13 signaling attenuates Th17 cytokine production. J.Immunol. 2009;182:5317–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newcomb DC, Boswell MG, Huckabee MM, et al. IL-13 regulates Th17 secretion of IL-17A in an IL-10-dependent manner. J.Immunol. 2012;188:1027–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.