Abstract

Photoacoustic imaging, a promising new diagnostic medical imaging modality, can provide high contrast images of molecular features by introducing highly-absorbing plasmonic nanoparticles. Currently, it is uncertain whether the absorption of low fluence pulsed light by plasmonic nanoparticles could lead to cellular damage. In our studies we have shown that a low fluence pulsed laser excitation of accumulated nanoparticles at low concentration does not impact cell growth and viability, while we identify thresholds at which higher nanoparticle concentrations and fluences produce clear evidence of cell death. The results provide insights for improved design of photoacoustic contrast agents and for applications in combined imaging and therapy.

1. Introduction

Plasmonic metallic nanoparticles (NPs) are near-ideal contrast agents for optical imaging. Due to surface plasmon resonance, the optical response of metallic NPs can provide extinction coefficients that are 4-5 orders of magnitude greater than dye alternatives [21]. The optical response of plasmonic NPs can be tuned by modifying their size and shape [22] or by modifying their surface characteristics [31]. Their small size allows systemic distribution in vivo [49], making NPs particularly useful contrast agents for medical imaging applications, such as optical coherence tomography [17], vital reflectance confocal microscopy [44], diffuse optical tomography [50], surface plasmon resonance imaging [15], and photoacoustic imaging [14, 38].

When light is absorbed by plasmonic NPs during optical imaging, thermal energy results from electron-phonon interactions [31]. Photoacoustic imaging uses this thermal energy to generate images of NPs within tissue. Photoacoustic imaging, which uses pulsed incident light to locally and transiently heating an absorber, detects the pressure wave resulting from the thermoelastic expansion of the heated absorber [10, 25]. This pressure wave propagates through tissue and can be received at tissue surfaces using an ultrasound transducer [37, 45, 48].

Plasmonic NPs are highly efficient photoacoustic imaging contrast agents due to their high optical absorption cross-sections and efficient thermal relaxation mechanisms [11, 32]. Additionally, since NPs can be conjugated to molecular targeting moieties, plasmonic NPs can be used to obtain an image of the molecular composition of a tissue region [3, 12, 34]. Taking full advantage of the optical wavelength tunability of plasmonic NPs, combined with tunable lasers for photoacoustic imaging, we can implement photoacoustic molecular imaging in a multiplex format, capable of distinguishing between multiple molecular receptors within a single tissue region [8, 30].

Besides providing imaging contrast, NPs can also be used for therapeutics. During photothermal therapy (PTT), laser heating of plasmonic NPs results in increased cell death in targeted regions containing gold NPs [19, 20, 33]. Applying an extended duration continuous wave laser (typically lasting minutes), as used for most PTT applications, leads to increased regional heating as a result of the NP photothermal processes; this increased heating likely causes protein denaturation leading to the observed cellular damage [13, 18]. However, when using a nanosecond pulsed laser to excite plasmonic NPs, it is not expected that bulk heating will be sufficient to lead to cell death. Accepted models of nanosecond laser-induced NPs heating and the subsequent conduction of heat to the surrounding environment predict a large temperature increase within the NPs during the laser pulse [28, 29], but this heat is dissipated through the environment during the time between pulses. Since nanosecond lasers used for photoacoustic imaging typically have a pulse interval greater than milliseconds, this rapid dissipation results in a negligible bulk temperature increase. Despite this, several groups have demonstrated the ability to cause cell death by exciting plasmonic NPs with nanosecond laser pulses [35, 46, 53]. The mechanisms of cell death are likely to be a combination of photothermal, pressure, and photochemical effects [42].

At this point, however, a comprehensive study of the impact of the nanosecond pulsed laser used during photoacoustic imaging of cells containing endocytosed NPs is lacking. We sought to establish guidelines for “safe” imaging versus therapeutic applications of nanosecond pulsed laser irradiation of NP-labeled cells. Typically, researchers can rely upon the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) safety guidelines to determine safe laser fluences for imaging [1]; however, our experiments show that these limits are insufficient for estimating the damage threshold for plasmonic nanoparticle-loaded cells exposed to nanosecond laser pulses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Gold nanosphere synthesis

Gold nanospheres were synthesized using seed-mediated growth as previously described [47]. A 71 mL volume of 0.27 mM HAuCl4 in nanopure water was brought to a boil under reflux. A 3.75 mL volume of 34 mM sodium citrate was added to the solution under vigorous stirring, and allowed to stir for several minutes. Then the solution temperature was allowed to return to room temperature. To make larger nanospheres, 7.5 mL of 25 mM HAuCl4 was mixed with 15.61 mL of 0.2 M NH2OH and 750 mL of nanopure water. To that solution under vigorous stirring, 50 mL of the as-prepared 20 nm seed solution was added. The nanoparticles were allowed to sit overnight, and characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Zeta potential and dynamic light scattering to determine the optical absorption properties, surface charge, and diameter, respectively.

2.2 Cell culture and nanoparticle loading

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 at 95% relative humidity. Standard cell culture techniques required media to be exchanged every 2-3 days and cells were passaged when 90% confluent. For these experiments, we cultured J774A.1 cells (mouse macrophages), MDA-MB-435 (cancer cells), and NIH-3T3 (human fibroblasts). Cells were passaged with trypsin (MDA-MB-435 and NIH-3T3) or by using a cell scraper (J774A.1). For experimentation, cells were passaged, counted using a hemacytometer, and reseeded in 96-well plates or flasks at a concentration of 1×105 cells/mL. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight prior to addition of nanoparticles.

Prior to incubation with cells, a polyethylene gycol (PEG) coating was added to minimize cytotoxicity [36], and the nanoparticles were sterilized and resuspended into cell media. First, a 10μM solution of 5000 kDa methyl-terminated PEG-thiol was prepared in nanopure water. This solution was added to the as-prepared nanosphere solution at a 1:10 ratio, and then vortexed for 30 minutes. The PEGylated nanospheres were rinsed twice in nanopure water via centrifugation at 500 rcf in 100kDa centrifugal filter tubes. After rinsing, the nanoparticles were centrifuged again and resuspended in phenol red-free DMEM. To sterilize the nanoparticles, the nanoparticle solution was dispensed through a 0.2 μm syringe filter. To incubate cells with the nanoparticles, the standard DMEM solution was aspirated from the cultured cells, and replaced with equal volume of the sterilized nanoparticles in phenol red-free DMEM. To vary the number of nanoparticles per cell, nanoparticle solutions were prepared at varying concentrations (typically, 4.5×105 NP/mL, 4.5×104 NP/mL, 4.5×103 NP/mL, 4.5×102 NP/ml, and 4.5×101 NP/mL). Prior to exposing cells to laser, excess nanoparticles were removed by gently aspirating and dispensing fresh phenol-red free media 3 times.

2.3 Pulsed laser exposure

Cells were exposed to laser fluence, varied using neutral density filters and recorded using a power meter, emitted by a New Wave Research Polaris II model laser generating 4 ns laser pulses at a wavelength of 532 nm, with a frequency of 20 Hz.

2.4 Cellular assays

The impact of the laser upon the cells was assessed using several conditional cell assays. Cell viability was assessed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium salt (MTS; CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega). MTS is reduced by living cells into a formazan product which absorbs at 490 nm. Immediately after laser exposure, 20 μL of MTS were added to each well containing cell samples, and the samples were incubated for two hours at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. The absorbance at 490nm was read using a microplate reader (Biotek Synergy HT). Absorbance values obtained were normalized to samples of untreated cells and samples of cells incubated with 70% ethanol for 30 minutes. A calcein-AM (CAM) and ethidium homodimer III (EthD-III) combination stain (Live/Dead Staining kit, Promokine) was used to compare the quantity of cells living and dead. Calcein-AM is a cell membrane permeable fluorescent dye which is hydrolyzed to cell membrane-impermeable, green-fluorescent (515 nm emission peak) Calcein by cellular esterases in living cells. EthD-III is a cell membrane-impermeable dye which can pass through disrupted cell membranes and intercalate with the nuclear DNA, emitting red fluorescence at 620 nm. Cells treated with laser were rinsed three times with sterile DPBS. CAM and EthD-III were prepared at 1.6 μM and 4 μM respectively for assay of the J774A.1 cells, and 1.2 μM and 5 μM for assay of the MDA-MB-435 and NIH-3T3 cells. After final rinse, 100μL of the assay solution was applied to the samples, incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, and the fluorescence was read for both dyes on the microplate reader. Additionally, Annexin V (Annexin V FITC Assay Kit, Cayman Chemical) was used to measure cellular apoptosis. Annexin V binds to phosphatidylserine expressed on the cell membrane of apoptotic cells. Fluorescence from the FITC-conjugated annexin V was used to probe for indicators of apoptosis.

2.5 Endocytosed nanoparticle quantification

Quantification of nanoparticle uptake was achieved using inductively-coupled plasmon mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Concurrent with each experiment, cells were seeded in a 25 cm3 flask, incubated with the sterilized nanoparticles for two days, rinsed three times and then passaged. The cells were counted, centrifuged into a pellet, and excess media was removed. Cell pellets were frozen until they were acid digested. To digest the cell samples, the pellets were resuspended in 300 μL of 70% nitric acid, heated to 60°C for over 14 hours. Then, one drop of 37% hydrochloric acid was added, and the volume was brought to 2 mL with nanopure water. ICP-MS gold standards were prepared using an AAS gold standard solution, which was diluted in an acid matrix of 3.5% nitric acid. Samples were diluted with the acid matrix as necessary prior to injection on the ICP-MS. Based on the original grams of gold in the nanoparticle synthesis and the size of the final nanoparticles determined using TEM, the calibrated ICPMS counts were used to calculate the average number of gold nanoparticles per cell.

3. Results

To assess the impact of photoacoustic imaging of nanoparticle-loaded cells, we chose to use 50 nm gold nanospheres, as verified by TEM and DLS, since this is an optimal size for inducing endocytosis [4].

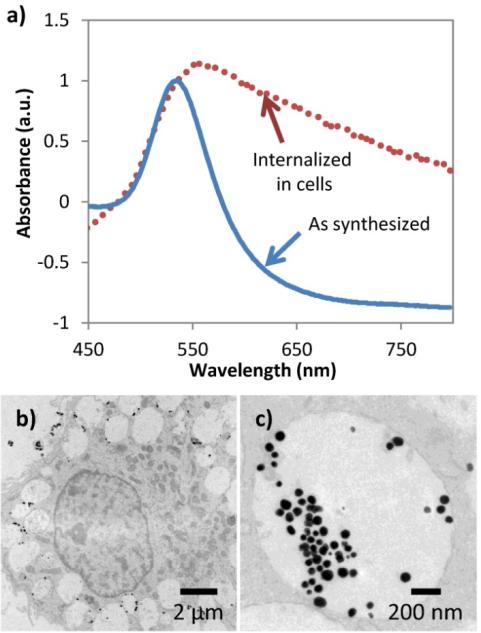

We varied the concentration of NPs during incubation to replicate reported in vivo concentrations of NP uptake, varying from 100 NPs/cell to 10000 NPs/cell [7, 39, 41]. As shown in figure 1a), the as-synthesized gold NPs have optical absorption spectra with a peak optical absorption at 530 nm. After cells have endocytosed the NPs, an increase in optical absorption in the near infrared occurs, due to the expected clustering of the endocytosed NPs and resulting surface plasmon resonance coupling [2]. As shown in figure 1b) and c), TEM images of macrophage cells after the incubation with the NPs show the NPs are clustered within large late-stage endosomes or lysosomes.

Figure 1.

Characterization of gold nanoparticles (NPs) and cellular endocytosis. a) UV-Vis of gold nanoparticles (NPs) before and after endocytosis. Background scattering due to cells alone has been subtracted, and absorbance has been normalized. b) and c) TEM images of macrophage cells with endocytosed 50 nm gold NPs.

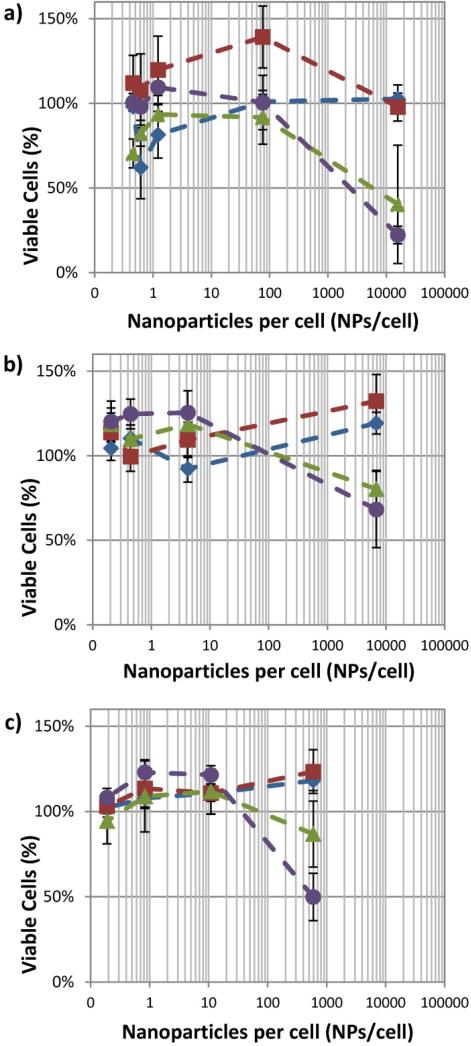

The cellular response when varying laser fluence was determined in the presence of varying concentrations of endocytosed gold nanospheres. Our results indicate that NP uptake is a significant factor affecting the cell viability under nanosecond pulsed laser irradiation. As shown in figure 2, each cell type shows a similar trend in cell viability assayed by MTS. The cell viability is heavily impacted by the number of NPs per cell. Secondly, the cell viability is influenced by the fluence of the laser – unsurprisingly, as the fluence is increased the reduction in cell viability becomes greater. Exposure to the nanoparticles and lower power laser initially causes an increase in the reduction of MTS, indicating an increase in cell viability. However, it is more likely that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by the stresses of nanoparticle and laser exposure are resulting in the observed increase in the formazan product. Significance testing was performed, first using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by two-sample t-tests. Based on the statistical analysis, general guidelines for cell viability can be established. The reduction in cell viability becomes statistically significant for fluences greater than 20 mJ/cm2 when there are greater than 500 NPs/cells (p<0.001). However, at lower concentrations (e.g. 76 NPs/cell for macrophages) fluences up to 36 mJ/cm2 show no significant loss in cell viability. Therefore, the number of NPs per cell is a critical parameter to determine non-damaging fluences appropriate for photoacoustic imaging.

Figure 2.

Viability of ) J774A.1, b) MDA-MB-435, and c) NIH-3T3 cells after exposure to nanosecond pulsed laser at laser fluences of 0 mJ/cm2 ( ), 12 mJ/cm2 (

), 12 mJ/cm2 ( ), 23 mJ/cm2 (

), 23 mJ/cm2 ( ), and 36 mJ/cm2 (

), and 36 mJ/cm2 ( ). (n = 6 microplate wells)

). (n = 6 microplate wells)

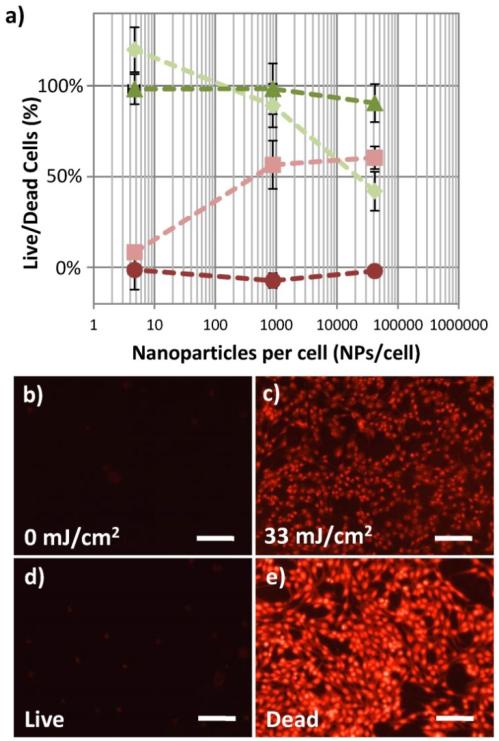

The cell viability was confirmed by applying a Live/Dead combined calcein-AM and EthD-III assay. As shown in figure 3a, in the absence of laser exposure, as the concentration of NPs is increased the quantities of living and dead macrophage cells are not significantly different. In contrast, when the cells are exposed to 1000 pulses of 29 mJ/cm2 fluence laser, the quantity of living cells decreases, while the quantity of dead cells increases. This is statistically significant (p<0.001) above 880 NPs/cell for this data set (not statistically significant for the lowest NPs concentration shown in this figure, which was 5 NPs/cell). Additionally, the disruption of the cell membrane, leading to necrotic cell death, is confirmed visually by fluorescence microscopy in the MDA-MB-435 cells. As shown in the fluorescent microscopy images in figure 3b, samples with 8200 NPs/cell, unexposed to the pulsed laser, contain very few cells with red fluorescence, while cells with the same NPs concentration exposed to 33 mJ/cm2 laser fluence show a large population of necrotic cells with permanently permeabilized cell membranes, since the EthD-III dye is applied after laser exposure. For comparison, cells without NPs, not exposed to laser (“live” control), are shown in figure 3d, while cells which were killed by incubating with 70% ethanol for 30 minutes (“dead” control) show a large number of dead cells with strong EthD-III fluorescence (figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Live/Dead cellular assay showing decreasing percentage of living cells and increasing percentages of dead cells with increasing concentrations of NPs per cell. A) Fluorescence of calcein AM (live stain), ( ), and EthD-III (dead stain), (

), and EthD-III (dead stain), ( ), of macrophage cells incubated with 50 nm gold spheres remains unchanged with increasing concentrations of NPs per cell when no laser is applied. After 1000 pulses of 29 mJ/cm2 laser fluence, significant changes in the percentage of macrophage cells living, (

), of macrophage cells incubated with 50 nm gold spheres remains unchanged with increasing concentrations of NPs per cell when no laser is applied. After 1000 pulses of 29 mJ/cm2 laser fluence, significant changes in the percentage of macrophage cells living, ( ), and dead, (

), and dead, ( ), are seen at NPs concentrations which are greater than 880 NPs/cell. (n = 6 microplate wells) The presence of a large population of dead cells stained by EthD-III after laser fluence is confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (b,c). The cells shown are MDA-MB-435 cells with 8200 NPs/cell. The fluorescent microscopy images of control cell populations which were not loaded with nanoparticles, one untreated (“Live”, d) and treated with 70% ethanol (“Dead”, e) are shown. Images obtained using a 20× objective (0.5 NA) and Leica 6000 DM microscope. Scale bars are 50 μm.

), are seen at NPs concentrations which are greater than 880 NPs/cell. (n = 6 microplate wells) The presence of a large population of dead cells stained by EthD-III after laser fluence is confirmed by fluorescence microscopy (b,c). The cells shown are MDA-MB-435 cells with 8200 NPs/cell. The fluorescent microscopy images of control cell populations which were not loaded with nanoparticles, one untreated (“Live”, d) and treated with 70% ethanol (“Dead”, e) are shown. Images obtained using a 20× objective (0.5 NA) and Leica 6000 DM microscope. Scale bars are 50 μm.

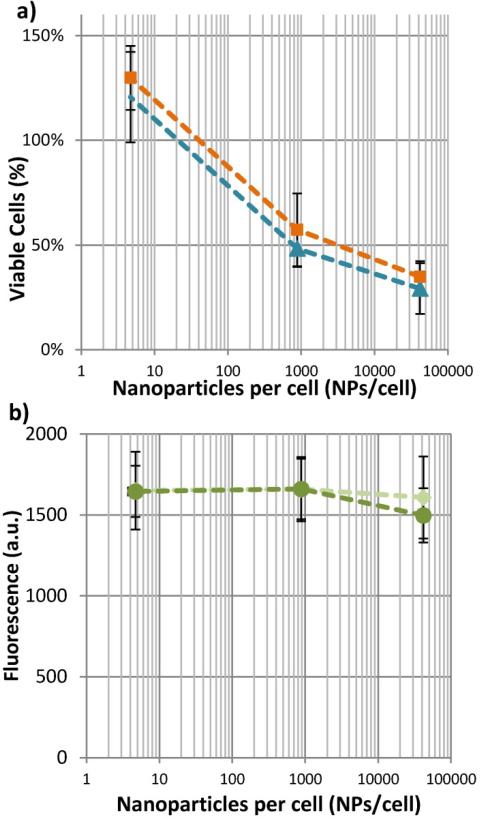

As indicated by the live/dead assay, this effect is a necrotic event, rather than apoptotic. For confirmation that apoptosis has not been induced at the highest fluences tested in these studies, cells incubated with NPs and exposed to 29 mJ/cm2 pulsed laser were assayed twenty-four hours after the laser exposure using MTS. The percentage of viable cells from 0 to 24 hours after laser exposure remains the same (figure 4a). Additionally, an assay for Annexin V shows that there is no increase in the quantity of apoptotic cells, when comparing cells incubated with varying concentrations of NPs and exposed to fluence of 0 mJ/cm2 or 33 mJ/cm2 (figure 4b). Therefore, it is unlikely that a significant population of cells are apoptotic. At the highest fluence of approximately 30 mJ/cm2, all cells are necrotic.

Figure 4.

After exposure to our highest laser fluence, macrophage cells impacted by the laser are necrotic, not apoptotic. As shown in a), whether the MTS assay component are added immediately after laser exposure, ( ), or 24 hours after laser exposure, (

), or 24 hours after laser exposure, ( ), does not change the number of viable cells. Likewise, b) shows that the presence of apoptotic cell markers cannot be detected at either 0 mJ/cm2, (

), does not change the number of viable cells. Likewise, b) shows that the presence of apoptotic cell markers cannot be detected at either 0 mJ/cm2, ( ) or 33 mJ/cm2, (

) or 33 mJ/cm2, ( ). (n = 6 microplate wells)

). (n = 6 microplate wells)

4. Discussion

Our in vitro experiments demonstrate that low fluence nanosecond laser pulses can cause significant necrosis in multiple cells lines loaded with plasmonic NPs. The implication of this result for diagnostic photoacoustic imaging is that one must be cautious when imaging near-infrared plasmonic NPs. Following ANSI guidelines, at laser wavelengths between 700 nm to 1000 nm, the allowable skin exposure for nanosecond pulses increases from 20 mJ/cm2 to 100 mJ/cm2. Based on these guidelines, it would be acceptable to irradiate tissue at 1000 nm with 100 mJ/cm2 fluence; however, the presence of plasmonic NPs which strongly absorb at 1000 nm, such as gold nanorods, can induce cellular necrosis under these conditions. Since photothermal relaxation processes are proportional to the extinction cross section of the NPs, the extinction cross section (which can be calculated for 50 nm gold spheres [21]) can be used to determine the fluence and concentration thresholds appropriate for other nanoparticle materials and geometries of known extinction cross section.

The mechanism of cell destruction remains to be determined. First, we consider the possibility that the photothermal effects are causing temperatures sufficient to cause cell damage. Using models of nanosecond pulsed lasers interacting with plasmonic NPs, we estimate the temperature of the NPs could reach 2100K after a 30 mJ/cm2 laser pulse [28]. The temperature increase in the surrounding environment is about half that of the temperature increase within the NPs itself,[52] and the spatial extent of this increased temperature varies approximately with 1/r3, where r is the radius of the NPs being heated [6]. Thus, despite large temperature increases within the NP itself, these increased temperatures are confined to a region within approximately 1.5r. In the case of a 50 nm particle, only proteins within ~75 nm of the NPs surface would be denatured by this increased temperature. Using a nanosecond laser, the duration of heating is short enough (approximately 3x the laser pulse duration), that the heat will diffuse and not result in bulk heat accumulation [29]. Given these spatial and temporal limitations, is unlikely that protein denaturation would be sufficiently wide-spread within the cell to cause immediate cell necrosis. It could be plausible that the heating results in the disruption of nearby lipid bilayers. Major disruption of the endosomal and lysosomal lipid bilayers can result in cell necrosis [9].

In addition to the discussed photothermal heating mechanisms, it is also possible that the pressure transients generated by the photoacoustic effect could lead to cell death. For example, pressure can cause morphological and functional changes including the loss of integrity of the plasma membrane [27]. Researchers have observed the loss of integrity of plasma membranes, indicated by the uptake of FITC-dextran, during pulsed laser exposure to cell-associated NPs so this is a plausible mechanism for cell death when using a nanosecond laser to excite NPs [40, 51]. Others have studied the threshold for laser-induced cavitation [26, 53]. The lowest observed cavitation threshold was 88 mJ/cm2, using a 0.5 ns pulse and clusters of 30 nm gold particles [26]. Last, we cannot exclude the possibility of a photochemical effect, for example a photochemical generation of reactive oxidative species (ROS) [24]. In the absence of light excitation, gold nanoparticles can reduce levels of reactive oxidative species and reactive nitrate species, which may be responsible for an increase in cell viability after incubation with the gold nanoparticles [43] in comparison to the negative control samples.

The experimental results indicate that the mechanism of cell death results in necrosis, rather than apoptosis. Therefore, the observed effect is leading to acute and immediate cell injury. It is possible that at laser fluences or NP concentrations intermediate to the viable and necrotic conditions, the laser-stimulated nanoparticles could trigger apoptotic pathways.

Based on our current understanding of the photothermal effects, it is likely that the safe laser fluence threshold would be increased if the NPs were on the exterior of the cell, in comparison to endocytosed within the cell. This could lead to more effective targeting strategies; to increase the safe laser fluence and improve the sensitivity of photoacoustic imaging, it may be useful to develop and optimize targeting strategies which do not result in cellular endocytosis, and instead fix nanoparticles to the cell membrane. Additionally, it is often of interest to image and concurrently perform therapy on tissue regions of interest. Since plasmonic NPs have both optical and photothermal properties, combined imaging and diagnostics or “theranostics” is highly sought for multiple applications, for example by combining photoacoustic imaging and PTT [5, 16, 23]. Our work demonstrates that it may not be necessary to combine a continuous wave laser with the nanosecond pulsed imaging laser in order to create a therapeutic effect – imaging could be performed at a fluence below 20 mJ/cm2, and then the fluence could be increased to affect cell death; alternatively, a low concentration of nanoparticles could be injected for imaging contrast, followed by injection at a higher dose for therapy.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated the viability of cells containing endocytosed plasmonic NPs after exposure to a low fluence nanosecond pulsed laser, typical of that used during photoacoustic imaging. At NPs concentrations similar to what is typically used for enhanced contrast during in vivo photoacoustic imaging, cell damage can result. However, if photothermal therapy is the goal, it is possible to perform therapy at fluences below the ANSI laser safety limit by increasing cellular uptake to more than 500 NPs/cell.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grants F32CA159913 (C.L. Bayer) and R01CA149740. We also thank Dr. Dwight Romanovicz of the University of Texas at Austin Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology and Laura Ricles of the Department of Biomedical Engineering for assistance with TEM imaging and sample preparation. We thank Ian Riddington of the Mass Spectrometry Facility of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UT Austin for assistance with ICP-MS. In addition, we thank Dr. Kimberly Homan at the University of Texas at Austin for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers. Laser Institute of America; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaron J, Travis K, Harrison N, Sokolov K. Dynamic Imaging of Molecular Assemblies in Live Cells Based on Nanoparticle Plasmon Resonance Coupling. Nano Letters. 2009;9:3612–8. doi: 10.1021/nl9018275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal A, Huang SW, O'Donnell M, Day KC, Day M, Kotov N, Ashkenazi S. Targeted gold nanorod contrast agent for prostate cancer detection by photoacoustic imaging. J. Appl. Phys. 2007;102 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albanese A, Tang PS, Chan WCW. The Effect of Nanoparticle Size, Shape, and Surface Chemistry on Biological Systems. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012;14:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Au L, Chen J, Wang LV, Xia Y. Gold nanocages for cancer imaging and therapy Methods. Mol. Biol. 2010;624:83–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-609-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baffou G, Quidant R. Thermo-plasmonics: using metallic nanostructures as nano-sources of heat. Laser Photon. Rev. 2012:n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balogh L, Nigavekar SS, Nair BM, Lesniak W, Zhang C, Sung LY, Kariapper MS, El-Jawahri A, Llanes M, Bolton B. Significant effect of size on the in vivo biodistribution of gold composite nanodevices in mouse tumor models. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2007;3:281–96. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayer CL, Chen YS, Kim S, Mallidi S, Sokolov K, Emelianov S. Multiplex photoacoustic molecular imaging using targeted silica-coated gold nanorods. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2011;2:1828–35. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunk UT, Dalen H, Roberg K, Hellquist HB. Photo-oxidative disruption of lysosomal membranes causes apoptosis of cultured human fibroblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997;23:616–26. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calasso IG, Craig W, Diebold GJ. Photoacoustic point source. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:3550–3. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y-S, Frey W, Aglyamov S, Emelianov S. Environment-Dependent Generation of Photoacoustic Waves from Plasmonic Nanoparticles. Small. 2011;8:47–52. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copland JA, Eghtedari M, Popov VL, Kotov N, Mamedova N, Motamedi M, Oraevsky AA. Bioconjugated gold nanoparticles as a molecular based contrast agent: implications for imaging of deep tumors using optoacoustic tomography. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2004;6:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickerson EB, Dreaden EC, Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Chu H, Pushpanketh S, McDonald JF, El-Sayed MA. Gold nanorod assisted near-infrared plasmonic photothermal therapy (PPTT) of squamous cell carcinoma in mice. Chem. Lett. 2008;269:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eghtedari M, Oraevsky A, Copland JA, Kotov NA, Conjusteau A, Motamedi M. High sensitivity of in vivo detection of gold nanorods using a laser optoacoustic imaging system. Nano Letters. 2007;7:1914–8. doi: 10.1021/nl070557d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sayed IH, Huang X, El-Sayed MA. Surface plasmon resonance scattering and absorption of anti-EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles in cancer diagnostics: Applications in oral cancer. Nano Lett. 2005;5:829–34. doi: 10.1021/nl050074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emelianov SY, Li PC, O'Donnell M. Photoacoustics for molecular imaging and therapy Phys. Today. 2009;62:34–9. doi: 10.1063/1.3141939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Near-infrared resonant nanoshells for combined optical imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Letters. 2007;7:1929–34. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodrich GP, Bao L, Gill-Sharp K, Sang KL, Wang J, Payne JD. Photothermal therapy in a murine colon cancer model using near-infrared absorbing gold nanorods. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010;15:018001–8. doi: 10.1117/1.3290817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, Sershen SR, Rivera B, Price RE, Hazle JD, Halas NJ, West JL. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:3549–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang XH, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2115–20. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain PK, Lee KS, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Calculated absorption and scattering properties of gold nanoparticles of different size, shape, and composition: Applications in biological imaging and biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:7238–48. doi: 10.1021/jp057170o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jana NR, Gearheart L, Murphy CJ. Seed-mediated growth approach for shape-controlled synthesis of spheroidal and rod-like gold nanoparticles using a surfactant template. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:1389–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J-W, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Moon H-M, Zharov VP. Golden carbon nanotubes as multimodal photoacoustic and photothermal high-contrast molecular agents. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:688–94. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krpetić Z e, Nativo P, Sée V, Prior IA, Brust M, Volk M. Inflicting Controlled Nonthermal Damage to Subcellular Structures by Laser-Activated Gold Nanoparticles. Nano Letters. 2010;10:4549–54. doi: 10.1021/nl103142t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kruger RA. Photoacoustic ultrasound. Med. Phys. 1994;21:127–31. doi: 10.1118/1.597367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapotko D. Optical excitation and detection of vapor bubbles around plasmonic nanoparticles. Opt. Express. 2009;17:2538–56. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.002538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Doukas A. Laser-generated stress waves and their effects on the cell membrane. IEEE J Sel. Top. Quant. 1999;5:997–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letfullin RR, George TF, Duree GC, Bollinger BM. Ultrashort Laser Pulse Heating of Nanoparticles: Comparison of Theoretical Approaches. Adv. Opt. Tech. 20082008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letfullin RR, Iversen CB, George TF. Modeling nanophotothermal therapy: kinetics of thermal ablation of healthy and cancerous cell organelles and gold nanoparticles. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2011;7:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li P-C, Wang C-RC, Shieh D-B, Wei C-W, Liao C-K, Poe C, Jhan S, Ding A-A, Wu Y-N. In vivo photoacoustic molecular imaging with simultaneous multiple selective targeting using antibody-conjugated gold nanorods. Opt. Express. 2008;16:18605–15. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.018605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Shape and size dependence of radiative, non-radiative and photothermal properties of gold nanocrystals. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2000;19:409–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Gonzalez MG, Niessner R, Haisch C. Strong size-dependent photoacoustic effect on gold nanoparticles: a sensitive tool for aggregation-based colorimetric protein detection. Anal. Methods. 2012;4:309–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loo C, Lowery A, Halas N, West J, Drezek R. Immunotargeted Nanoshells for Integrated Cancer Imaging and Therapy. Nano Lett. 2005;5:709–11. doi: 10.1021/nl050127s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallidi S, Larson T, Aaron J, Sokolov K, Emelianov S. Molecular specific optoacoustic imaging with plasmonic nanoparticles. Opt. Express. 2007;15:6583–8. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.006583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nedyalkov N, Atanasov P, Toshkova R, Gardeva E, Yossifova L, Alexandrov M, Karashanova D. Laser heating of gold nanoparticles: photothermal cancer cell therapy. 2012;8427:84272P–1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niidome T, Yamagata M, Okamoto Y, Akiyama Y, Takahashi H, Kawano T, Katayama Y, Niidome Y. PEG-modified gold nanorods with a stealth character for in vivo applications. J. Controlled Release. 2006;114:343–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oraevsky AA, Jacques SL, Esenaliev RO, Tittel FK. Time-resolved optoacoustic imaging in layered biological tissues. OSA Proc. 19941994:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oraevsky AA, Karabutov AA, Savateeva EV. Enhancement of optoacoustic tissue contrast with absorbing nanoparticles. Proc. SPIE. 2001;4434:60–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrault SD, Walkey C, Jennings T, Fischer HC, Chan WC. Mediating tumor targeting efficiency of nanoparticles through design. Nano Letters. 2009;9:1909–15. doi: 10.1021/nl900031y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitsillides CM, Joe EK, Wei X, Anderson RR, Lin CP. Selective Cell Targeting with Light-Absorbing Microparticles and Nanoparticles. Biophys J. 2003;84:4023–32. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian X, Peng X-H, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie S. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat. Biotech. 2007;26:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin Z, Bischof JC. Thermophysical and biological responses of gold nanoparticle laser heating. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1191–217. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15184c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shukla R, Bansal V, Chaudhary M, Basu A, Bhonde RR, Sastry M. Biocompatibility of gold nanoparticles and their endocytotic fate inside the cellular compartment: a microscopic overview. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2005;21:10644–54. doi: 10.1021/la0513712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sokolov K, Follen M, Aaron J, Pavlova I, Malpica A, Lotan R, Richards-Kortum R. Real-time vital optical imaging of precancer using anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1999–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su JL, Wang B, Wilson KE, Bayer CL, Chen Y-S, Kim S, Homan KA, Emelianov SY. Advances in clinical and biomedical applications of photoacoustic imaging. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 2010;4:497–510. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2010.529127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi H, Niidome T, Nariai A, Niidome Y, Yamada S. Gold nanorodsensitized cell death: microscopic observation of single living cells irradiated by pulsed near-infrared laser light in the presence of gold nanorods. Chemical Letters. 2006;35:500–1. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J. The Formation of Colloidal Gold. J Phys Chem. 1953;57:670–3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Xu Y, Xu M, Yokoo S, Fry ES, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography of biological tissues with high cross-section resolution: reconstruction and experiment. Med Phys. 2002;29:2799–805. doi: 10.1118/1.1521720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West JL, Halas NJ. Engineered nanomaterials for biophotonics applications: Improving sensing, imaging, and therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2003;5:285–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu C, Liang X, Jiang H. Metal nanoshells as a contrast agent in near-infrared diffuse optical tomography. Opt. Commun. 2005;253:214–21. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao CP, Qu XC, Zhang ZX, Huttmann G, Rahmanzadeh R. Influence of laser parameters on nanoparticle-induced membrane permeabilization. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14 doi: 10.1117/1.3253320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng N, Murphy AB. Heat generation by optically and thermally interacting aggregates of gold nanoparticles under illumination. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:375702. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/37/375702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zharov VP, Mercer KE, Galitovskaya EN, Smeltzer MS. Photothermal nanotherapeutics and nanodiagnostics for selective killing of bacteria targeted with gold nanoparticles. Biophys J. 2006;90:619–27. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]