Abstract

Freshwater snails of the family Lymnaeidae play an important role in the transmission of fascioliasis worldwide. In Vietnam, 2 common lymnaeid species, Lymnaea swinhoei and Lymnaea viridis, can be recognized on the basis of morphology, and a third species, Lymnaea sp., is known to exist. Recent studies have raised controversy about their role in transmission of Fasciola spp. because of confusion in identification of the snail hosts. The aim of this study is, therefore, to clarify the identities of lymnaeid snails in Vietnam by a combination of morphological and molecular approaches. The molecular analyses using the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA clearly showed that lymnaeids in Vietnam include 3 species, Austropeplea viridis (morphologically identified as L. viridis), Radix auricularia (morphologically identified as L. swinhoei) and Radix rubiginosa (morphologically identified as Lymnaea sp.). R. rubiginosa is a new record for Vietnam. Among them, only A. viridis was found to be infected with Fasciola spp. These results provide a new insight into lymnaeid snails in Vietnam. Identification of lymnaeid snails in Vietnam and their role in the liver fluke transmission should be further investigated.

Keywords: Fasciola, Austropeplea viridis, Radix auricularia, Radix rubiginosa, Vietnam

INTRODUCTION

Fascioliasis is a worldwide parasitic disease caused by Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica. The latter species is common in temperate zones especially in Europe, the Americas, and Australia, whereas the former is the most prevalent species in tropical regions of Africa and Asia [1]. In Vietnam, human and animal fascioliasis has drawn a special interest. Indeed, the prevalence of human fascioliasis was found to be on the rise in the country. About 10,000 cases were detected in central Vietnam in 2011 alone [2]. Based on molecular data, F. gigantica and hybrid forms were identified.

The Lymnaeidae are one of the most widespread groups of freshwater snails and many of them act as intermediate hosts of important digenean trematodes that infect humans or livestock [3]. The correct taxonomic classification of these snails solely based on morphological characteristics was not always possible and the nomenclature of Lymnaeidae is extremely confused [4,5]. Additionally, environmental conditions are responsible for morphological variation which further complicates identification [5,6]. There are few studies dealing with morphology and phylogenetics of lymnaeids in Asia. Using morphological criteria, Thanh [7] recognized 2 common lymnaeid species, Lymnaea viridis and Lymnaea swinhoei, in northern Vietnam in 1980. Currently, the former is generally referred to as Austropeplea viridis and the second as Radix auricularia [8], and these are the names we shall use throughout this paper. An additional species, Lymnaea sp., was identified in Vietnam by Doanh [9] in 2012. Two species, A. viridis (as L. viridis) and R. auricularia (as L. swinhoei), were reported by some authors to act as intermediate hosts of Fasciola spp. in Vietnam [10,11]. Others indicated that only 1 of these species was an intermediate host [9,12]. In Taiwan, China, Japan, and Thailand, R. rubiginosa, R. auricularia, and A. viridis have been reported as hosts for Fasciola spp. [13-15]. Previous to this study, no analysis of molecular sequence data from lymnaeids had been done in Vietnam. Therefore, the aim of this study is to use both molecular and morphological criteria in order to identify the potential vectors of Fasciola spp. in the country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Snail sampling

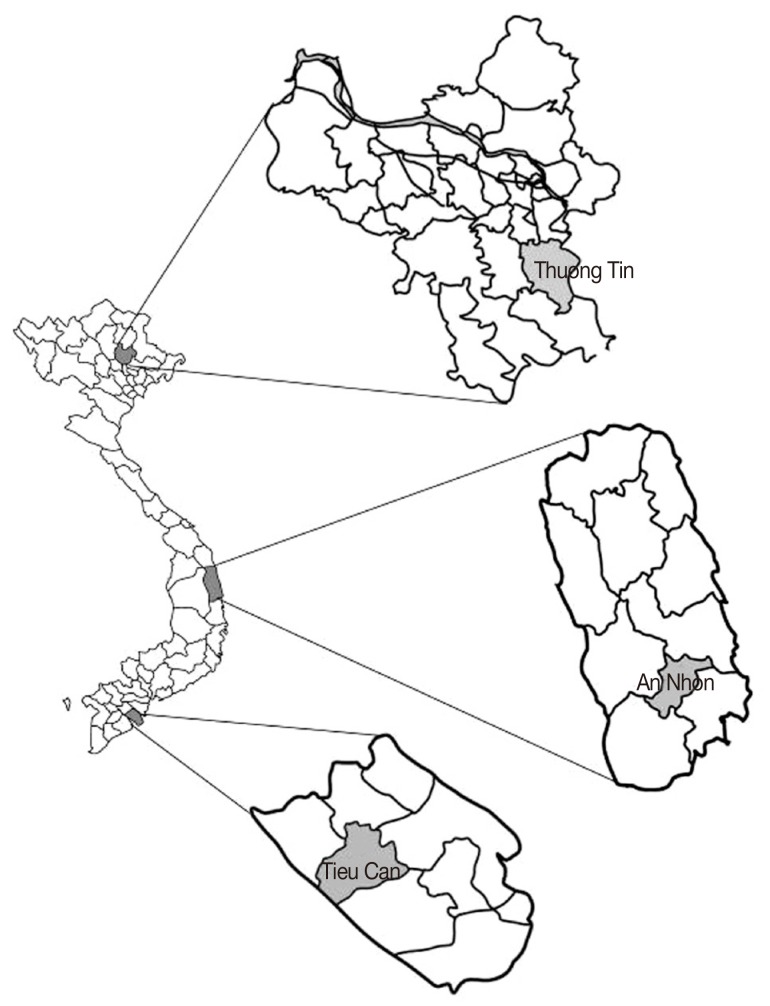

Lymnaeid snails were collected in a variety of water bodies in 3 localities of Vietnam representing major climatic types: Thuong Tin district, Ha Noi capital (N: 20°84'75"; E: 105°90'87" - northern part); An Nhon district, Binh Dinh Province (N: 13°94'47"; E: 109°07'96" - central part); and Tieu Can district, Tra Vinh Province (N: 9°80'77"; E: 106°18'55" - southern part) (Fig. 1). Individual snails were morphologically sorted out, then examined for the presence of Fasciola spp. larval stages by stereomicroscopy. Representatives of each morphological group were individually fixed in 100% ethanol for subsequent molecular identification.

Fig. 1.

Map of sampling locations (Thuong Tin districts, Ha Noi Capital; An Nhon, Binh Dinh Province; Tieu Can district, Tra Vinh Province)

Morphological examinations

Snails were killed by immersion in hot water (70℃) for 15 sec and then transferred to water at room temperature. Stereomicroscopic examination was performed using an Olympus SZ51, SZX-ILL-B2 200 (Hai Ninh company, Ha Noi, Vietnam). The following criteria/measurements were recorded for each snail: form, apex whorls, body whorls, transparency, and the ratio of apex/body [16]. Pictures were taken with a digital camera Nikon D3x (Photogallerry Liège-Sauvenière, Belgium), and manipulated for presentation using Adobe Illustrator CS3 (TDT company, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam). Morphological identifications were based on Burch [17].

Detection of Fasciola spp. larval stages by microscopy

All samples were checked under the stereomicroscope for cercariae. For this purpose, whole snails were crushed between 2 glass plates. Larvae were identified according to the keys of Schell [18].

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

DNA was individually extracted from each snail type using the Chelex®-based DNA extraction technique [19]. A single individual was extracted for each shell type. Only a small piece of foot tissue was used for the extraction of DNA. The material was mechanically disrupted with the help of a Kimbe® Kontes disposable pellet mixer (Sigma-Aldrich, Chinh Chuong company, Ha Noi, Vietnam) in 100 µl of Chelex® 5% (Bio-Rad, TABC company, Ha Noi, Vietnam) and incubated for 1 hr and then for 30 min at 56℃ and 95℃, respectively, in a Master Gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf, BCE company, Ha Noi, Vietnam). Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 7 min. The supernatant, containing the DNA, was carefully transferred to another tube. The rDNA ITS-2 was amplified using primers previously described [4]. Reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 µl containing 5 µl Mastermix 2X (Fermentas, TABC company, Ha Noi, Vietnam) 0.4 µl MgCl, 1 µl dNTP, 1 µl of each primer, 0.6 µl water, and 1 µl of genomic DNA. The thermal cycling profile was 3 min at 94℃ followed by 35 cycles of 30 sec at 94℃, 30 sec at 55℃, 30 sec at 72℃, and a final elongation step at 72℃ for 5 min [20]. Amplified fragments were sequenced by Macrogen Inc., using an ABI 3730XL (Seoul, Korea).

Sequence analyses

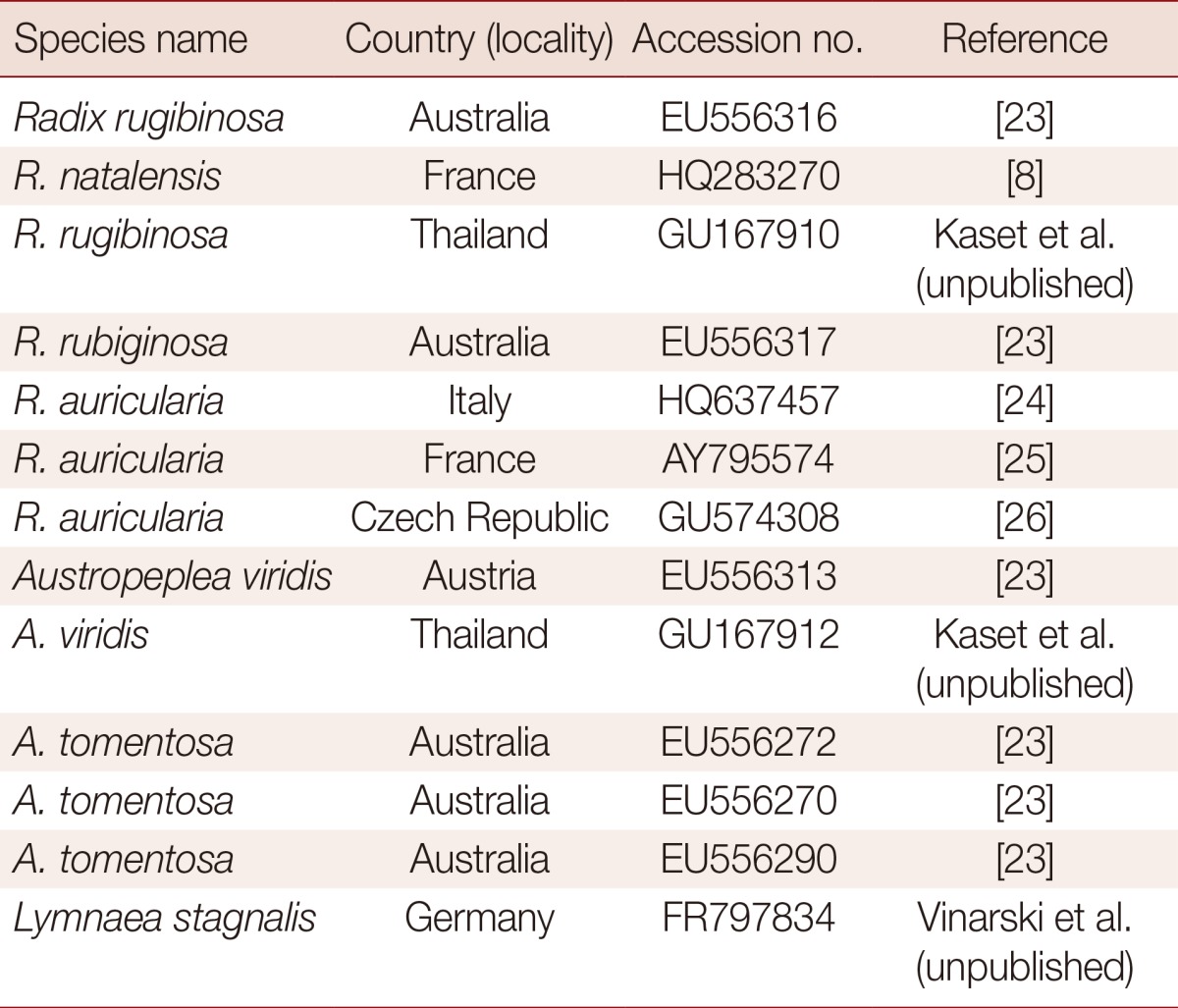

Sequences were carefully edited "by eyes" and then aligned using CLUSTAL-W version 1.8 [21] and MEGA v5.2.2 [22] (S. McAllister Ave, Phoenix, Arizona, USA). Subsequently, minor corrections were manually introduced for a better fit of nucleotide correspondences in regions of simple sequence repeats. Tree construction was carried out in MEGA 5.2.2. The analyses were carried out using the sequences of our lymnaeid species together with 13 previously published ITS-2 sequences of closely related lymnaeid species. A sequence from Lymnaea stagnalis was used as an out-group (Table 1) [8,15,23-26]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method implemented in MEGA 5.2.2. The substitution model used was the Kimura 2 parameter model+gamma (allowing for unequal rates among sites). Clade support was assessed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Table 1.

Geographical location and Genbank accession number of the lymnaeid snails used in the phylogenetic study

RESULTS

Morphological identification of lymnaeid snails

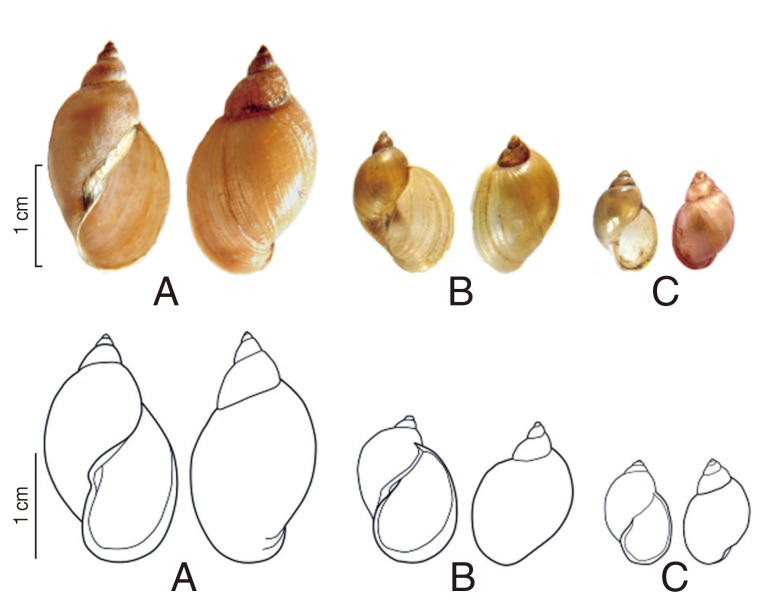

Three morphological types of snails were distinguished based on the key of Burch [17].

Type 1 (Fig. 2A): Shell is elongated and cylindrical. Shell height/width: 11-20/5-8 mm. There are 5 whorls; the last is large and inflated. Spire is high and aperture height/width: 7-11/4-5 mm. Aperture is large but not extended and moderately expanded. The outer margin is S-shaped. Columella generally twisted, is making a fold. This morphological description led to the identification of Lymnaea sp.

Fig. 2.

Morphology of the snails. (A) Radix rubiginosa (="Lymnaea sp."). (B) Radix auricularia ("L. swinhoei"). (C) Austropeplea viridis (="L. viridis").

Type 2 (Fig. 2B): Shell is large but smaller than type 1. Shell height/width: 12-18/8-10 mm. Shell is thin with sharp apex. There are 4 whorls, the last inflated with convex angle in the left. Shell surface is smooth, thin and brown with clear ribs. Aperture is large, ear-shaped, and extended. Aperture height/width: 9-10/6-8 mm. Columella is curved in the middle. The lower part of the outer lip is rounded. This morphological description led to the identification of R. swinhoei (=L. swinhoei) Adam, 1866.

Type 3 (Fig. 2C): Shell is much smaller than the 2 other species. Shell height/width: 10-13/4-6 mm. There are 4.5-5 well-rounded whorls, the first of which are small compared to the swollen last whorl. Shell surface is smooth, thin and brown with clear ribs. The aperture is regularly oval without angles. Aperture height/width: 5-6/3-4 mm. The outer lip is sharp, regularly curved. Columella is generally straight, without a fold. This morphological description led to the identification of A. viridis (=L. viridis) Quoy and Gaimard, 1832.

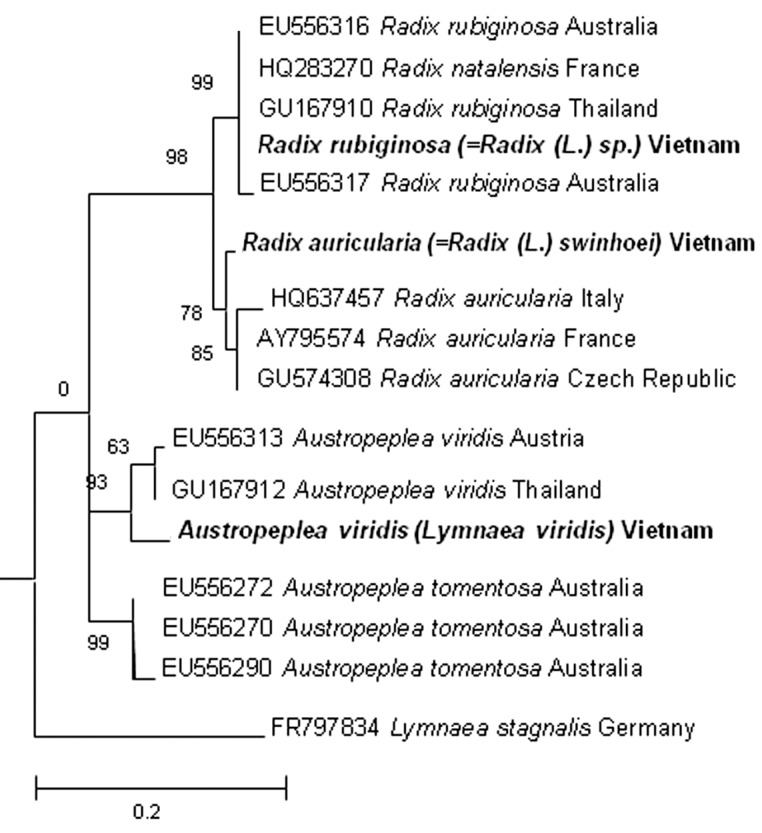

Ribosomal DNA sequence analysis and phylogenetic tree construction

The molecular analyses based on the ITS-2 sequences strongly supported 3 morphological types. Their length of ITS2 sequences (type 1, 450; type 2, 470, and type 3, 451 bp) which were deposited in Genbank with the accession no. KF042385 (for type 1), KF042386 (for type 2), and KF042387 (for type 3), were various. The results of Blastn showed that type 1 had a 99% identity with R. rubiginosa (EU556316), supporting its identification as this species. Similarly, ITS2 sequence of type 2 showed 99% homology with those of R. auricularia (HQ637457). Type 3 was closest to A. viridis (GU167912) with 94% identity. In the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3), type 1, 2, and 3 from Vietnam were clustered with R. rubiginosa, R. auricularia, and A. viridis, respectively, confirming their identification.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on lymnaeid ITS-2 rDNA sequences constructed with MEGA 5.2.2 using maximum likelihood analysis. Lymnaea stagnalis from Germany was used as an outgroup. The bootstrap values are shown at the branches.

Snail distribution

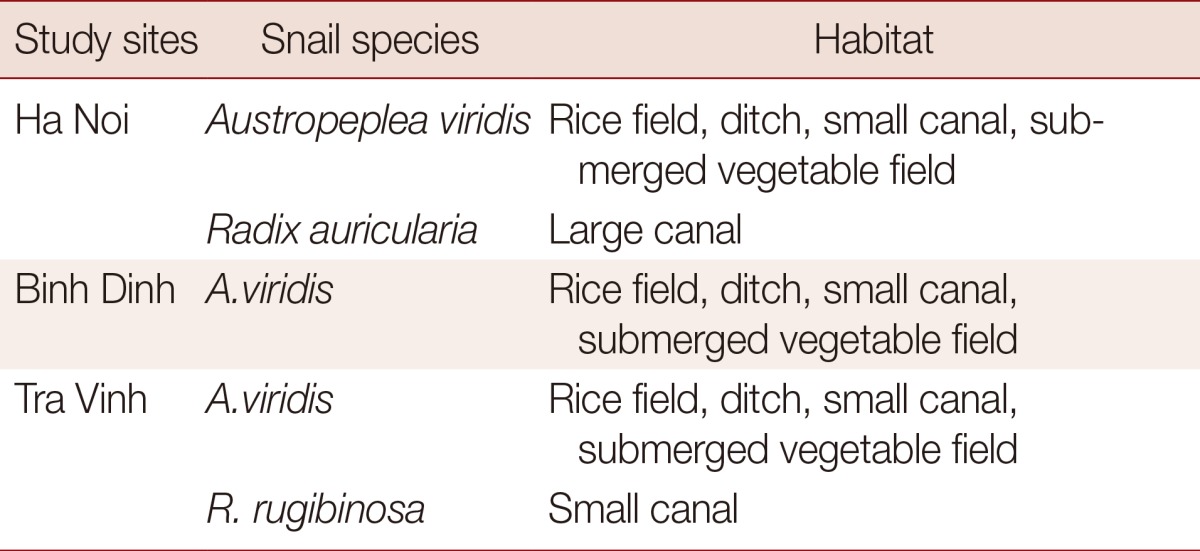

A. viridis is a common species found in various water bodies (rice fields, ditches, small canals, and submerged vegetable fields) and was present in the 3 areas investigated. R. auricularia was found in large canals in the northern part of Vietnam only, while R. rubiginosa was found only in small canals in the southern part (Table 2).

Table 2.

Snail distributions in different areas under investigation

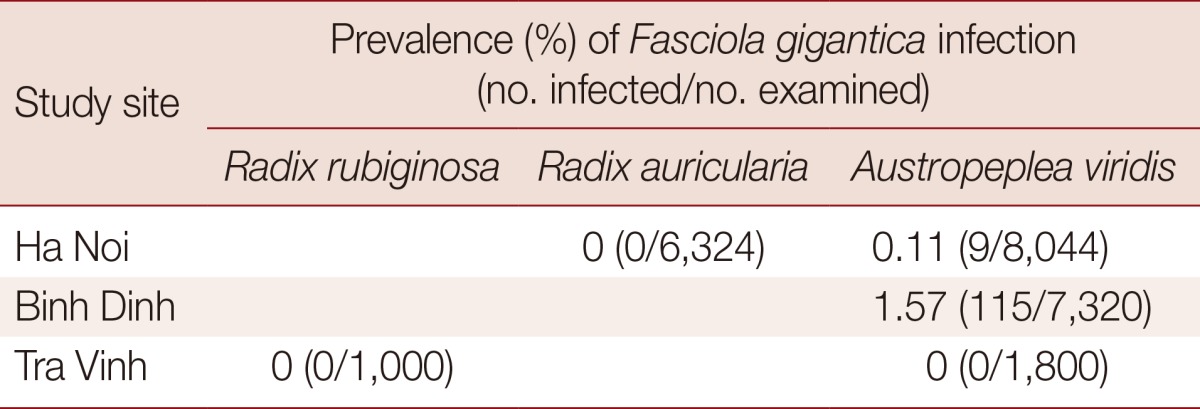

Prevalence of Fasciola spp. infection in field-collected snails

Table 3 shows that only 1 species (A. viridis) was infected with F. gigantica cercariae in the field with the infection rates of 0.11% (9/8,044) in Ha Noi and 1.57% (115/7,321) in Binh Dinh.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Fasciola spp. infection in lymnaeid snails

DISCUSSION

According to the key of Burch [17] reported in 1980, we identified 2 genera of lymnaeids in Vietnam: Austropeplea Cotton 1942 (columella generally straight, without a fold or plait at the apertural end) and Radix Montfort, 1810 (columella generally twisted, making a fold or plait at the apertural end). The genus Austropeplea was represented by a single species, A. viridis (=L. viridis). The 2 Radix species, R. swinhoei (=L. swinhoei) and R. rubiginosa (=Lymnaea sp.) had a quite similar morphology and consequently were difficult to identify according to morphological criteria only. This might be due to the phenotypic plasticity of the shell shape. Indeed, in numerous gastropod species, including the Lymnaeidae, the shell shape may vary according to environmental conditions [5,6]. In particular, shell morphology seems not to be critical for identifying species of the genus.

DNA-taxonomy is a reliable, comparable, and objective means for species identification in biological research and enabled to identify these species. Several gene regions have been used in taxonomic and phylogenetic studies of the Lymnaeidae, such as ITS-1, ITS-2, 16S, 18S, and CO1 [4,6,27]. Among them, the rDNA ITS-2 has been the most often used molecular maker in lymnaeid studies to date [27]. Our result has confirmed the correct name of 3 lymnaeid snail species in Vietnam based on molecular rDNA ITS-2 analysis, R. rubiginosa, R. auricularia, and A. viridis. Among them, R. rubiginosa is a new record for a freshwater snail fauna in Vietnam.

The 3 lymnaeids occur in somewhat different habitats. A. viridis is widely distributed [8, 35]. In our investigation, this species was common in all 3 regions (northern, central, and southern Vietnam). It can be found in rice fields, ditches, small canals, and submerged vegetable fields. By contrast, R. auricularia is found only in large stagnant canals. The species with the most restricted distribution was R. rubiginosa, which can be found at very low densities in small canals in southern Vietnam.

Based on microscopic examinations, R. auricularia (=R. swinhoei) and A. viridis (=L. viridis) were reported to be infected with Fasciola spp. in Vietnam [10,28]. Other authors reported that either R. auricularia or A. viridis could be infected with Fasciola spp. [9,12]. This was probably due to a lack of experience in mollusk identification; the name of the species was just given without pictures, description, or measurement, and the prevalence of infection. This point was also mentioned in a recent study [9]. Our results have shown that only A. viridis is infected with Fasciola spp. and at a low prevalence. The low prevalence observed might be a consequence of low sensitivity of microscopical examination in detecting intra-molluscan stages. Methods based on PCR might reveal higher incidences of infection [19], but this approach has yet to be used in the country.

In this study, we have confirmed that R. swinhoei (based on morphology) was in fact R. auricularia (based on PCR/sequencing). Although R. auricularia was reported to act as the intermediate host for F. gigantica in Africa, Asia, and USA, its role as the intermediate host for F. gigantica in Vietnam remains unclear because we did not find any infected individuals. The susceptibility of other lymnaeid snails to Fasciola spp. in Vietnam requires experimental studies.

The combined use of morphological and molecular data both under laboratory and field conditions, particularly on morphologically similar species of lymnaeid snails which act as potential intermediate hosts for Fasciola spp., should allow clarification of some key elements on the epidemiology of human and animal fascioliasis in Vietnam.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC) Mixed PhD program, Belgium. We would like to thank our collaborators and staff in Laboratory of Parasitology and Parasitic Diseases, Department of Infectious and Parasitic diseases, University of Liège, Belgium, and Department of Parasitology, Department of Molecular Systematic and Conservation Genetic, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Vietnam for technical help.

References

- 1.Mas-Coma MS, Esteban JG, Bargues MD. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis: a review and proposed new classification. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:340–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trung TN, Chuong NV. Raising number of human fascioliasis cases in 2011 and demand for disease prevention at the community. Quy Nhon: Annual Rep Instit Malariol Parasitol Entomol; 2012. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton JP. Fasciolosis. Wallingford Oxon OX10 8DE, UK: CABI Publishing, CAB International; 1998. pp. 1–544. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa AC, Escobar JS, Noya O, Velásquez LE, Gonzáles-Ramírez C, Hurtrez-Boussès S, Poitier JP. Morphological and molecular characterization of neotropic Lymnaeidae (Gastropoda: Lymnaeoidea), vectors of fasciolosis. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1978–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubendick B. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar. 17th ed. Stockkholm Almqvist and Wiksells Boktryckeri AB; 1951. Recent Lymnaeidae, their variation, morphology, taxonomy, nomenclature and distribution; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfenninger M, Cordellier M, Streit B. Comparing the efficacy of morphologic and DNA-based taxonomy in the freshwater gastropod genus Radix (Basommatophora, Pulmonata) BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thanh DN, Bai TT, Mien PV. Identification of invertebrate in northern Vietnam. Ha Noi, Vietnam: Science and Technology Publishing House; 1980. pp. 230–250. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correa AC, Escobar JS, Durand P, Renaud F, David P, Jarne P, Poitier JP, Hurtrez-Bousses S. Bridging gaps in the molecular phylogeny of the Lymnaeidae (Gastropoda: Pulmonata), vectors of Fascioliasis. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:381. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doanh PN, Hien HV, Duc NV, Thach DTC. New data on intermediate host of Fasciola in Vietnam. J Biol. 2012;34:139–144. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen ST, Nguyen DT, Nguyen TV, Huyen VV, Le DQ, Fukuda Y, Nakai Y. Prevalence of Fasciola in cattle and of its intermediate host Lymnaea snails in central Vietnam. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:1847–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim NT, Vinh PT. Investigation on the prevalence of fasciolosis in cattle and snails in Ha Bac midland and prevention method. Ha Noi, Vietnam: Annual Rep Instit Agricult Sci; 1997. pp. 407–411. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngai DD, Luc PV, Duc NV, Doanh PN, Ha NV, Minh NT. Animal raising practice and liver fluke prevalence in cattle in Daklak province. J Biol. 2006;8:68–72. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itagaki T, Fujiwara S, Mashima K, Itagaki H. Experimental infection of Japanese Lymnaea snails with Australian Fasciola hepatica. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. 1988;50:1085–1091. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.50.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Xu L, Li L, Jiang L, Yang S, Yang G, Lang C. The experiment on artificial hatching and Radix swinhoei infection from Fasciola hepatica's eggs. Yunnan Agricultural University. 2004;19:360–364. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaset C, Eursithichai V, Vichasri-Grams S, Viyanant V, Grams R. Rapid identification of lymnaeid snails and their infection with Fasciola gigantica in Thailand. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samadi S, David P, Jarne P. Variation of shell shape in the clonal snail Melanoides tuberculata and its consequences for the interpretation of fossil series. Evolution. 2000;54:492–502. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burch JB. A guide to the freshwater snails of the Philippines. Malacol Rev. 1980;13:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shell SC. How to know the trematodes. Dubuque, Iwoa, USA: WM C Brown Company Publisher; 1970. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caron Y, Righi S, Lempereur L, Saegerman C, Losson B. An optimized DNA extraction and multiplex PCR for the detection of Fasciola sp. in lymnaeid snails. Vet Parasitol. 2011;178:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artigas P, Bargues MD, Sierra RLM, Agramunt VH, Mas-Coma S. Characterisation of fascioliasis lymnaeid intermediate hosts from Chile by DNA sequencing, with emphasis on Lymnaea viator and Galba truncatula. Acta Trop. 2011;120:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. Mega molecular evolotionary genetics analysis. copyright 1993-2013. Available from: http://www.megasoftware.net/

- 23.Puslednik L, Ponder WF, Dowton M, Davis AR. Examining the phylogeny of the Australasian Lymnaeidae (Heterobranchia: Pulmonata: Gastropoda) using mitochondrial, nuclear and morphological markers. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;52:643–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cipriani P, Mattiucci S, Paoletti M, Scialana F, Nascetti G. Molecular evidence of Trichobilharzia franki Muller and Kimmig, 1994 (Digenea: Schistosomatidae) in Radix auricularia from Central Italy. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferté H, Depaquit J, Carré S, Villena I, Léger N. Presence of Trichobilharzia szidati in Lymnaea stagnalis and T. franki in Radix auricularia in northeastern France: molecular evidence. Parasitol Res. 2005;95:150–154. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huňová K, Kašný M, Hampl V, Leontovyč R, Kuběna A, Mikeš L, Horák P. Radix spp.: identification of trematode intermediate hosts in the Czech Republic. Acta Parasitol. 2012;57:273–284. doi: 10.2478/s11686-012-0040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durand P, Poitier JP, Escoubeyrou K, Arenas JA, Yong M, Amarista M, Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S, Renaud F. Occurrence of a sibling species complex within neotropical lymnaeids, snail intermediate hosts of fascioliasis. Acta Trop. 2002;83:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bargues MD, Mas-Coma S. Reviewing lymnaeid vectors of fascioliasis by ribosomal DNA sequence analyses. J Helminthol. 2005;79:257–267. doi: 10.1079/joh2005297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan PD. Biological characteristic of Fasciola gigantica and fasciolosis in buffalo in northern Vietnam. J Sci Technol. 1983;12:675–678. (in Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]