Background: Aβ peptides are generated by stepwise cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein.

Results: Aβs longer than Aβ1–48 are efficiently cleaved by γ-secretase in cells with different response to inhibitors (GSIs) and modulators (GSMs).

Conclusion: The initial γ-secretase cleavage does not precisely define subsequent product lines.

Significance: Understanding how different species of Aβ are generated and modulated by small molecules has broad therapeutic implications.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid, Amyloid Precursor Protein, Intramembrane Proteolysis, Protease

Abstract

Understanding how different species of Aβ are generated by γ-secretase cleavage has broad therapeutic implications, because shifts in γ-secretase processing that increase the relative production of Aβx-42/43 can initiate a pathological cascade, resulting in Alzheimer disease. We have explored the sequential stepwise γ-secretase cleavage model in cells. Eighteen BRI2-Aβ fusion protein expression constructs designed to generate peptides from Aβ1–38 to Aβ1–55 and C99 (CTFβ) were transfected into cells, and Aβ production was assessed. Secreted and cell-associated Aβ were detected using ELISA and immunoprecipitation MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Aβ peptides from 1–38 to 1–55 were readily detected in the cells and as soluble full-length Aβ proteins in the media. Aβ peptides longer than Aβ1–48 were efficiently cleaved by γ-secretase and produced varying ratios of Aβ1–40:Aβ1–42. γ-Secretase cleavage of Aβ1–51 resulted in much higher levels of Aβ1–42 than any other long Aβ peptides, but the processing of Aβ1–51 was heterogeneous with significant amounts of shorter Aβs, including Aβ1–40, produced. Two PSEN1 variants altered Aβ1–42 production from Aβ1–51 but not Aβ1–49. Unexpectedly, long Aβ peptide substrates such as Aβ1–49 showed reduced sensitivity to inhibition by γ-secretase inhibitors. In contrast, long Aβ substrates showed little differential sensitivity to multiple γ-secretase modulators. Although these studies further support the sequential γ-secretase cleavage model, they confirm that in cells the initial γ-secretase cleavage does not precisely define subsequent product lines. These studies also raise interesting issues about the solubility and detection of long Aβ, as well as the use of truncated substrates for assessing relative potency of γ-secretase inhibitors.

Introduction

Although it has been modified and challenged, the amyloid cascade hypothesis remains the most accepted hypothesis regarding the etiology of Alzheimer disease (1). The core tenant of this hypothesis—that accumulation of the amyloid β (Aβ)3 peptide aggregates in the brain triggers a complex pathophysiological process leading to widespread brain organ failure—is strongly supported by genetic, pathological modeling, and more recently clinical studies in living humans (2–4). In most cases of Alzheimer disease, Aβx-42 and possibly other longer Aβ peptides (e.g., Aβx-43) have been implicated as key pathogenic species that are at least required for initiating Aβ aggregation and accumulation (5–10). Thus, understanding how different species of Aβ are generated remains a critically important issue in Alzheimer disease and has important implications for development of therapies designed to affect production of Aβ.

Three proteolytic activities are involved in the secretory processing of amyloid β precursor protein (APP) (11). In the periphery, APP is primarily processed by α-secretase (12). α-Secretase primarily cleaves APP after residue 16 of Aβ, which is considered a nonamyloidogenic pathway. ADAM10 and 17 have been identified as the major α-secretases (13–15), although other proteases may also cleave APP near this site (e.g., BACE2) (11, 16). Aβ1-x is the cleavage product of APP by two other membrane-bound proteases: β- and γ-secretase. β-Secretase (BACE1) primarily cleaves APP at the N terminus of the Aβ peptide and releases the sAPPβ ectodomain (17–19). Cleavage of the resulting C-terminal fragment (CTF) by γ-secretase results in the release of Aβ (20, 21). As opposed to processing in peripheral cells and organs, a much greater amount of APP is processed in the amyloidogenic β-secretase pathway in the brain, especially in neurons (19).

γ-Secretase cleavage of APP CTFs has been proposed to occur in three distinct steps: (i) an initial ϵ-cleavage near the cytoplasmic face of the transmembrane domain that liberates the cytoplasmic tail of the substrate (22, 23), (ii) stepwise tri- or tetra-peptide carboxyl-peptidase-like cleavages, and (iii) a final cleavage releasing the Aβ peptide (24). The most commonly observed final products are Aβ1–37, 1–38, 1–39, 1–40, and 1–42 (25). Aβ1–45 and Aβ1–46 that can be generated during the stepwise cleavage have typically only been detected in the presence of certain γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) or in in vitro assays (26–28), although some studies have provided limited evidence that these species may be present in human and APP transgenic mouse brain (27, 29). Aβ1–48 and Aβ1–49, the main Aβs produced from the initial ϵ-cleavage are typically not detectable in physiological models, but their generation is inferred from the identification of the corresponding APP intracellular domains, C51 and C50 (22, 23). These ϵ-sites are considered the main initial cleavage sites within the APP CTF. A third site generating Aβ1–51 and the APP intracellular domain C49 has also been identified in broken cell γ-secretase assays and in presenilin APP mutant cell lines (30). Shorter Aβ peptides such as Aβ1–17 through Aβ1–20 have also been reported, but whether they are produced by γ-secretase alone or the combined action of γ-secretase and other proteases has not been resolved (25, 31–33).

Because there is evidence that the initial cleavage of APP at Aβ1–51 or Aβ1–48 generates a higher ratio of Aβ1–42, whereas cleavage at Aβ1–49 generates higher levels of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 have been proposed to be generated from two different “product lines” in a stepwise cleavage model. Funamoto et al. (34) provided initial evidence for this model using truncated Aβ minigenes in which Aβ was expressed in mammalian cells as APP signal peptide:Aβ fusion proteins. Cells expressing Aβ1–49 generated predominantly Aβ1–40 and cells expressing Aβ1–48 generated much more Aβ1–42, although the absolute amount of Aβ generated was very low (∼0.2 pm compared with >200 pm from Aβ1–49). Takami et al. (24) subsequently provided direct evidence for stepwise cleavage using a very elegant strategy, which combined in vitro γ-secretase cleavage and LC-MS/MS to quantify the specific peptides that were postulated to be released during stepwise processing. They showed that Aβ1–40 can be preferentially derived from Aβ1–49 through sequential removing of ITL, VIV, and IAT peptides, whereas Aβ1–42 is preferentially derived from Aβ1–48 through sequential cleavage of VIT and TVI peptides. More recently, additional support for this stepwise cleavage model has come from several studies showing that FAD-linked mutations in APP and PSEN can not only shift the initial ϵ-cleavage site, but also can alter subsequent processivity, thus increasing the relative production of long Aβ peptides (35, 36). One of these studies also suggested that Aβ1–38 arises from an additional stepwise cleavage of Aβ1–42 (36), a finding directly supported by a recent study showing that Aβ1–42 could be further processed into Aβ1–38 in vitro, whereas Aβ1–43 is cleaved into both Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–38 (37).

In the present study, we further explored the sequential cleavage model initially proposed by Ihara and co-workers (24, 34) using BRI2-Aβ1-x fusion proteins that produced Aβ peptides ranging from 1–38 to 1–55. We have previously employed this strategy to efficiently express individual Aβ proteins in cells and in the brains of transgenic mice (38–40). Because many of the studies supporting a stepwise cleavage model for γ-secretase processing of APP have been performed in in vitro assays or in cells utilizing signal peptide Aβ peptide expression constructs that produce Aβ peptides that are inefficiently secreted, we hypothesized that the BRI2 fusion protein strategy, which results in efficient processing and secretion of Aβ from the fusion protein, might provide a more physiologic system to assess γ-secretase processivity. Although our studies further support the sequential γ-secretase cleavage model, they show that in cells the initial γ-secretase cleavage site does not absolutely define subsequent product lines. Unexpectedly, we also find (i) that under some circumstances long Aβ peptides generated in cells following processing of the BRI2 fusion protein are efficiently secreted as intact soluble peptides; (ii) that the long Aβ peptides dramatically decrease the relative potency of multiple GSIs compared with the potency of the same GSIs when APP or C99 is used as a substrate; and (iii) that two PSEN1 mutants selectively alter processing for Aβ1–51, but not Aβ1–49.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA and Cell Culture

Fusion constructs encoding the first 243 amino acids of BRI2 protein followed by Aβ peptides encompassing various Aβ species from Aβ38 to Aβ55 or C99 (99 amino acids on the C-terminal of APP) were generated as previously described (38). The fragments were ligated into the expression vector pAG3. Sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. The overexpression was performed by transiently transfecting human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) and CHO cells. Cells were grown in either DMEM (HEK) or Ham's F-12 (CHO) media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Briefly, 2.7 μg of DNA was applied to a 75% confluent 6-well plate (Corning) using the polycation polyethylenimine transfection method (41). When BRI2-Aβ constructs were co-transfected with either wild-type PSEN1 or the mutants M139V or Δexon9 into CHO cells, 1.35 μg of each DNA were used. In some experiments, 10-cm dishes were used with appropriately adjusted amounts of DNA. Cells were incubated with transfection reagent for 12–16 h, after which the growth medium was replaced with fresh medium. DMSO (Sigma), GSIs, or GSMs were added to the appropriate concentration. The GSIs L685,458 and MRK680 were purchased from Tocris; the GSMs sulindac sulfide and fenofibrate were purchased from Sigma. (Z-LL)2 ketone was from Calbiochem. LY411,575, GSM1, and compound 2 were synthesized by A. Fauq at the Mayo Clinic Chemical Core. 24 h later, the medium was collected for assay by ELISA and MS. Stable CHO cell lines were selected with 0.8 μg/ml hygromycin B. To evaluate any potential non-γ-secretase-mediated proteolytic cleavage of the long secreted Aβs, 1 μm synthetic Aβ1–49 was incubated with CHO cells overnight, and then Aβ in the media was analyzed by immunoprecipitation MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (IP/MS), as described below. A sample with 1 μm synthetic Aβ1–49 in fresh media was used as control.

Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry

50 μl of magnetic sheep anti-mouse IgG beads (Invitrogen) were incubated with 4.5 μg of Ab5 antibody for 30 min at room temperature with constant shaking. The beads were then washed with PBS and incubated with 1–10 ml of conditioned medium, to which 0.1% Triton X-100 was added for 1 h. For cell lysate IP, cells from a 10-cm dish were washed twice with PBS and then incubated with 1 ml of PBS with 1% Triton X-100 on ice for 20 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C with the resulting supernatants diluted with 9 ml PBS and incubated with Ab5-pretreated beads. Bound beads were washed sequentially with 0.1% and 0.05% octyl glucoside (Sigma) followed by water. Samples were eluted with 10 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) in water. 2 μl of elute was mixed with an equal volume of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Sigma) solution in 60% acetonitrile, 40% methanol. 1 μl of sample mixture was loaded to α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid pretreated MSP 96 target plates (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA). The samples were analyzed with a Bruker Microflex (Bruker Daltonics Inc.) mass spectrometer.

Aβ ELISA

Sandwich ELISAs used for Aβ detection was performed as described previously (42). Aβ40 and Aβ42 were captured with mAb 13.1.1 (human Aβ35–40 specific) and mAb 2.1.3 (human Aβ35–42 specific), respectively (43, 44). Both were detected with HRP-conjugated mAb Ab5 (human Aβ1–16 specific) (45). Total Aβ was captured with mAb Ab5 and detected by HRP-conjugated mAb 4G8 (Covance, Princeton, NJ). All ELISAs were developed with TMB substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD).

In Vitro Assay

Aβ1–48, Aβ1–49, and C99 (CTF99 plus a methionine at the N-terminal and FLAG tag at the C-terminal) were used for in vitro assay. Aβ48 and Aβ49 were purchased from AAPPTEC (Louisville, KY). The peptides were pretreated with 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol. After drying, the peptides were dissolved in 0.1% ammonia hydroxide. C99 was purified as described with modifications (46). Briefly, inclusion bodies were dissolved in Tris·HCl-urea buffer (25 mm Tris, 8 m urea, pH 8.0). After addition to a HiTrap Q column (GE Healthcare), the column was washed with 10× column volume of Tris·HCl-urea buffer and then Tris·HCl-CHAPSO buffer (25 mm Tris, 1% CHAPSO, pH 8.0). C99 was eluted using Tris·HCl-CHAPSO buffer with NaCl gradient. Gel filtration and anti-FLAG M2 affinity column can be used if further purification is necessary. CHAPSO-solubilized γ-secretase was prepared from CHO S-1 cells as previously described (47). Briefly, S-1 cells were washed once with cold PBS and then resuspended in PBS with Complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). After nitrogen cavitation at 750 p.s.i. on ice for 1 h, cell debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h to pellet the total membranes. The membrane pellet was resuspended and homogenized in cold sodium bicarbonate buffer (100 mm NaHCO3, pH 11.0). After centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h, the pellet was solubilized with CHAPSO buffer (150 mm sodium citrate, 1% CHAPSO, 5 mm EDTA) by slightly vortex and incubated on ice for 1 h. The insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. For in vitro assay, substrates (25 μm for MS, 1 μm for ELISA) were incubated with CHAPSO solubilized γ-secretase (100 μg/ml protein concentration) in sodium citrate buffer (150 mm, 1× complete protease inhibitor, pH 6.8) for 3 h at 37 °C in the presence or absence of γ-secretase inhibitors.

RESULTS

BRI2-Aβ1-x Fusion Proteins Efficiently Produce Aβ Peptides Ranging from 1–38 to 1–55

We had previously employed the BRI2-Aβ1-x fusion protein strategy to efficiently generate Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in the late secretory pathway; additionally we had also shown that a BRI2-C99 (CTFβ) fusion protein efficiently generated C99 that could be subsequently processed by γ-secretase to Aβ (38, 40, 48, 49). Here we evaluated whether the BRI2 fusion protein strategy could be used to generate Aβ peptides spanning from 1–38 to 1–55 to examine their subsequent proteolyic processing. Expression plasmids encoding the various BRI2-Aβ1-x proteins were transiently transfected into HEK-293 cells with Aβ assessed in the cells and in the media by both Aβ ELISAs and IP/MS. Each transfected BRI2 fusion construct resulted in overexpression and secretion of the full-length Aβ1-x peptides as assessed by IP/MS (Fig. 1A). The calculated molecular mass for each peptide and the average observed molecular mass of each peptide are listed in Table 1. Overall, mass accuracy was within 0.05%. To determine whether the secreted Aβ1-x peptides were present in exosomes or present as soluble secreted proteins, conditioned media were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. Aβ1-x peptides remained in the supernatants with no depletion, indicating that they are produced as soluble proteins. Full-length Aβ1-x peptides were also detectable in the cell lysate (data shown for a subset of the fusion proteins, Fig. 1B). Western blotting of the cell lysate with BRI2 protein antibody and an antibody recognizing the N terminus of Aβ (6E10) demonstrated that the constructs were efficiently overexpressed (Fig. 1C). In the HEK-293 cell studies, we were not able to detect shorter Aβ cleavage products in the media by IP/MS. However using Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 ELISAs coupled with GSI treatment, we could establish that both Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were being produced by γ-secretase processing from constructs longer than Aβ1–47 (Fig. 2A). Compared with other constructs, BRI2-Aβ1–51 showed a different production profile, which generated significant amount of Aβx-42. Aβx-42 was detected by ELISA from Aβ1–43, 44, 45, 46, and 47, but this likely represents detection of these species by mm2.1.3, the anti-Aβx-42 antibody used for capture. This antibody, like most anti-Aβ42 antibodies, shows cross-reactivity with longer Aβ peptides. Indeed, GSI treatment did not significantly lower levels of Aβx-42 detected by ELISA from these Aβ species (Fig. 2B).

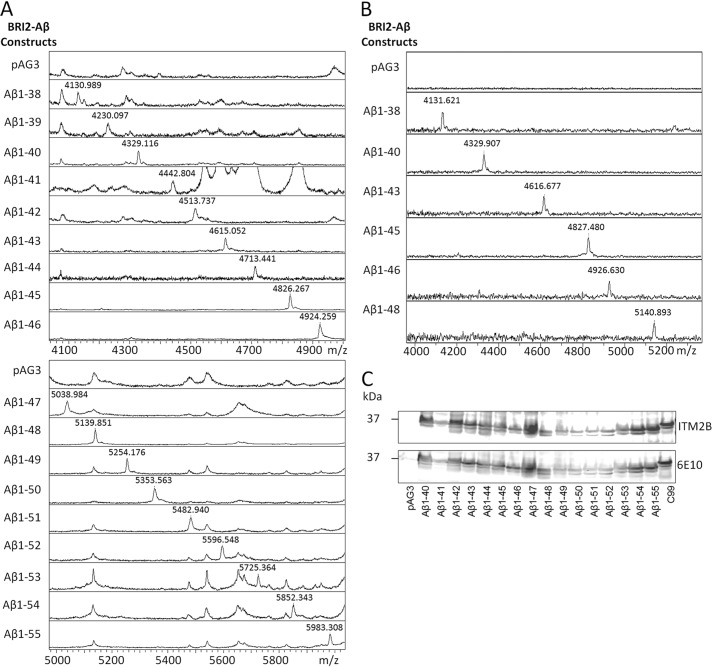

FIGURE 1.

BRI2-Aβ1-x overexpression and production profile in transiently transfected HEK 293T cells. A, IP/MS spectra from 1 ml of conditioned media from transiently transfected HEK 293T cells expressing the various BRI2-Aβ1-x vectors. The m/z value of peaks representing Aβ1-x peptides are labeled (also see Table 1). B, selected subset of IP/MS spectra from Triton X-100 cell lysates from the transiently transfected cells expressing the various BRI2-Aβ1-x vectors. C, overexpression of the BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs as detected by Western blotting of the cell lysates using an anti-BRI2 antibody ITM2b and the anti-Aβ1–16 antibody 6E10.

TABLE 1.

Molecular mass of Aβ peptide detected in the conditioned medium

| Construct | Molecular mass |

|

|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Observed | |

| Da | ||

| BRI2-Aβ1–36 | 4017.48 | 4018.04 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–37 | 4074.53 | 4074.13 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–38 | 4131.58 | 4130.99 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–39 | 4230.72 | 4230.10 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–40 | 4329.85 | 4329.12 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–41 | 4443.01 | 4442.80 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–42 | 4514.09 | 4513.74 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–43 | 4615.19 | 4615.05 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–44 | 4714.32 | 4713.41 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–45 | 4827.48 | 4826.27 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–46 | 4926.62 | 4924.26 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–47 | 5039.78 | 5038.99 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–48 | 5140.88 | 5139.85 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–49 | 5254.04 | 5254.18 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–50 | 5353.17 | 5353.56 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–51 | 5484.37 | 5482.94 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–52 | 5597.53 | 5596.55 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–53 | 5725.70 | 5725.36 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–54 | 5853.87 | 5852.34 |

| BRI2-Aβ1–55 | 5982.05 | 5983.31 |

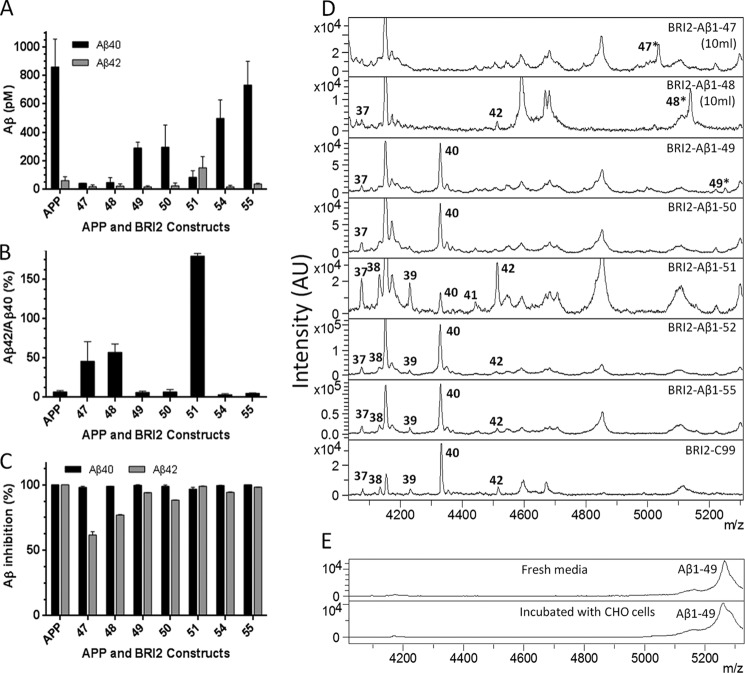

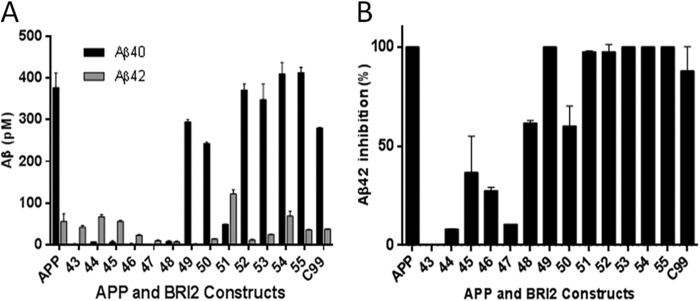

FIGURE 2.

Processing of BRI2-Aβ1-x in transiently transfected HEK 293T cells is detectable by Aβ ELISA. A, Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 ELISA of conditioned media from transiently transfected HEK 293T cells expressing the various BRI2-Aβ1-x vectors. B, percentage of inhibition of Aβx-42 determined by ELISA production for each construct in the presence of 1 μm LY411,575 compared with DMSO control. The numbers below each bar indicate the length of the corresponding BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs.

Aβ1-x Peptides Longer than Aβ1–48 Are Processed by γ-Secretase in CHO Cells

In parallel studies using select constructs transfected into CHO cells, we were able to detect processing of the secreted Aβ peptides produced from BRI2-Aβ fusion proteins longer than Aβ1–48 by both IP/MS and Aβ ELISA. Aβ ELISA results from CHO cells (both transiently and stably transfected) were similar to those from HEK-293 cells (Fig. 3, A and B). All constructs longer than Aβ1–48 appeared to be efficiently processed by γ-secretase to produce Aβx-40 and x-42 because 1 μm of the GSI LY-411,575 almost completely inhibited production of these Aβ peptides (Fig. 3C). Although the small amount of Aβ1–40 produced by Aβ1–47 or Aβ1–48 was also completely inhibited by the GSI, Aβ1–42 was not. The lack of complete inhibition of Aβ1–42 likely represents some detection of the full-length peptide by the ELISA. By IP/MS from 1 ml of media, intact Aβ1–47 from BRI2-Aβ1–47 cells and Aβ1–48 BRI2-Aβ1–48 could be detected. Although BRI2-Aβ1–48 was not efficiently processed by γ-secretase, it appeared to be processed preferentially to Aβ1–42, but not other processed Aβ species, and could be detected by IP/MS from 10 ml of conditioned media from BRI2-Aβ1–48 cells (Fig. 3D). Although small amounts of full-length Aβ1–49 could also be detected from cells expressing the BRI2-Aβ1–49 fusion protein, full-length species could not be detected from fusion proteins expressing longer Aβs (Aβ1–50 to 1–55). Consistent with the concept of a preferential product line for Aβ1–40, Aβ1–49 was cleaved predominately to Aβ1–40 and a small amount of Aβ1–37. Aβ1–50 showed a similar profile to Aβ1–49, although by ELISA a small amount of Aβ1–42 could be detected. In contrast, BRI2-Aβ1–51 showed a distinct profile producing a larger proportion of Aβ1–42 as assessed by both IP/MS and ELISA. Moreover, minor amounts of Aβ1–37, 38, 39, 40, and 41 were produced from the BRI2-Aβ1–51 construct. IP/MS profiles and ELISA data from BRI2-Aβ1–52, Aβ1–55, and C99 were similar, with each producing a typical spectrum of Aβ peptides with Aβ1–40 as the major species and minor amounts of Aβ1–37, 38, 39, and 42 detected. To evaluate the potential non-γ-secretase-mediated proteolytic cleavage of the long secreted Aβs, synthetic Aβ1–49 was incubated with CHO cells overnight, and then Aβ in the media was analyzed by IP/MS. These data revealed that Aβ1–49 is quite stable in the media and not cleaved to smaller Aβ species (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Constructs longer than Aβ1–48 are efficiently processed by γ-secretase in stable CHO cells. A, Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 ELISA of conditioned media from stable cell line transfected with various BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs. B, the ratio of Aβx-42 to Aβx-40 production of each BRI2-Aβ1-x construct is shown. C, percentage of inhibition of Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 determined by ELISA for each construct in the presence of 1 μm LY411,575 compared with DMSO control. D, IP/MS spectra of select BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs. 10 ml of conditioned media was used for the BRI2-Aβ1–47 and BRI2-Aβ1–48 constructs, with 1 ml used for the remaining constructs. Labels in the spectra indicate the corresponding Aβ peptide, e.g., 37 for Aβ1–37. Intact Aβ1–47, 48, and 49 are labeled with asterisks. Peaks without labeling are nonspecific. E, IP/MS spectra of fresh Ham's F-12 medium with 1 μm synthetic Aβ1–49 (top panel) and media from CHO cells that was incubated with 1 μm Aβ1–49 overnight (bottom panel).

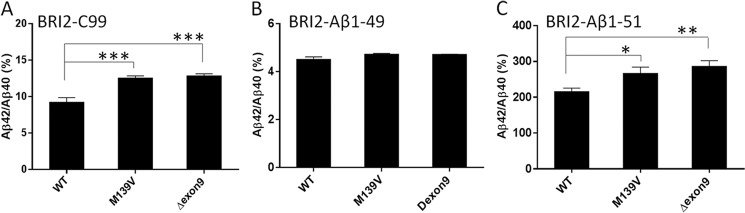

To determine whether FAD PSEN1 variants change the production of long Aβ substrates, PSEN1 wt, M139V and Δexon9 expression plasmids were transiently co-transfected into CHO cells along with expression plasmids for BRI2-C99, BRI2-Aβ1–49, or BRI2-Aβ1–51. When Aβ levels were assessed in the conditioned media using Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISAs, we found that both M139V and Δexon9 significantly increased the Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio from BRI2-C99 and BRI2-Aβ1–51 but not from BRI2-Aβ1–49 transfected cells (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

PSEN1 mutants increase Aβ42:Aβ40 from CHO cells expressing BRI2-C99 and BRI2-Aβ1–51 but not from cells expressing BRI2-Aβ1–49. PSEN1 WT, variant M139V, or Δexon9 was transiently co-transfected with BRI2-C99 (A), BRI2-Aβ1–49 (B), or BRI2-Aβ1–51 (C), and then Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 were measured by ELISA. The data represent the results from four to seven independent experiments, with two or three replicates in each experiment per condition. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

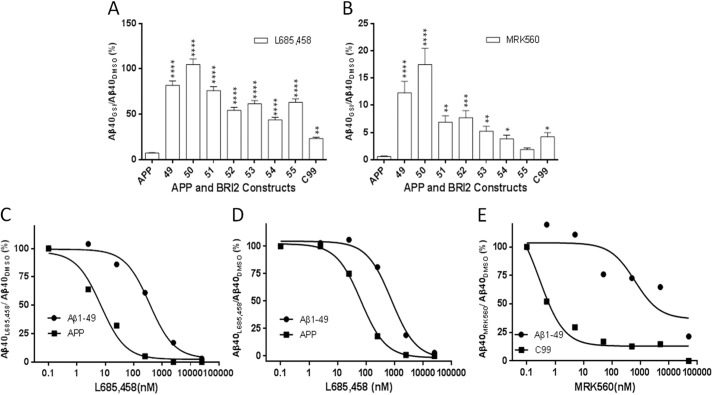

Truncated Substrates Alter IC50 values of Several GSIs but Do Not Alter Effect of GSMs

The effects of two GSIs (1 μm of L685,458 and 100 nm MRK560 (50, 51)) on production of secreted Aβ1–40 from cells transfected with BRI2-Aβ49 to BRI2-Aβ55, BRI2-C99, and APP was assessed by ELISA (Fig. 5, A and B). At these concentrations both GSIs showed much less ability to inhibit Aβ1–40 production from the BRI2-Aβ constructs compared with GSI effects on full-length APP and for L685,458; the BRI2-Aβ constructs also were less responsive to the GSI than BRI2-C99. To more fully explore this phenomena, we conducted dose-response studies comparing the effects of L685,458 on total Aβ and Aβ1–40 production from transiently transfected HEK 293 cells expressing BRI2-Aβ1–49 and APP (Fig. 5C). In these studies, the IC50 of L685,458 for inhibition of Aβ1–40 shifted from 6.9 nm for APP to 362 nm for BRI2-Aβ49 and for total Aβ shifted from 4.8 nm for APP to 14 μm for BRI2-Aβ49. Tests of L685,458 with stably transfected CHO cells show similar effects (Fig. 5D), with the IC50 for inhibition of Aβ1–40 shifted from 65.6 nm for APP to 771.3 nm for BRI2-Aβ49. Additional dose-response studies using the GSIs MRK560 and LY-411,575 (52) also show that the IC50 for inhibition of Aβ1–40 production from BRI2-Aβ1–49 is greatly increased as compared with APP (Table 2). We also assessed whether similar effects could be observed with in vitro γ-secretase assays using recombinant C99 and synthetic Aβ1–49 as substrate. As shown in Fig. 5E and Table 2, inhibition of Aβ1–40 production from Aβ1–49 (IC50 637 nm) was markedly less sensitive to inhibition by MRK560 than inhibition of C99 cleavage (0.3 nm).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of GSI on γ-secretase cleavage of long BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs. A and B, Aβx-40 production in the presence of 1 μm γ-secretase inhibitors L685,458 (A) or 0.1 μm MRK560 (B) using transiently transfected HEK cells. The ratio of Aβx-40 in the presence of inhibitors to Aβx-40 in the absence of inhibitors (DMSO) were used to evaluate the extent of inhibition. The data are expressed and graphed as means ± S.E. with statistical analysis performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc testing for group differences. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. C and D, dose response of L685,458 on Aβx-40 production in APP wild type and BRI2-Aβ1–49 from transiently transfected HEK-293 cells (C) or stable CHO cells (D), respectively. E, effect of MRK560 on Aβx-40 production in an in vitro γ-secretase assay using recombinant C99 and synthetic Aβ1–49.

TABLE 2.

IC50 values of select γ-secretase inhibitors on APP constructs

Each assay was repeated at least two times. The values in the table are the means ± standard errors.

| GSI | Cellsa | Total Aβ |

Aβ40 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP | BRI2-Aβ1–49 | APP | BRI2-Aβ1–49 | C99b | Aβ1–49c | ||

| nm | nm | ||||||

| L685,458 | HEK | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 1400.0 ± 90.0 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 362.4 ± 40.0 | ||

| L685,458 | CHO | 12.7 ± 9.1 | 279.4 ± 13.2 | 65.5 ± 2.1 | 771.3 ± 5.5 | ||

| MRK560 | HEK | 6.9 ± 1.5 | >500 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 53.3 ± 4.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 637.0 ± 15.0 |

| LY411,575 | HEK | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 4.30 ± 0.50 | ||||

| LY411,575 | CHO | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 3.26 ± 0.61 | ||||

a HEK 293 T cells were transient transfections; CHO cells are stable lines.

b Recombinant C99 (data generated from an in vitro assay).

c Synthetic Aβ1–49 (data generated from an in vitro assay).

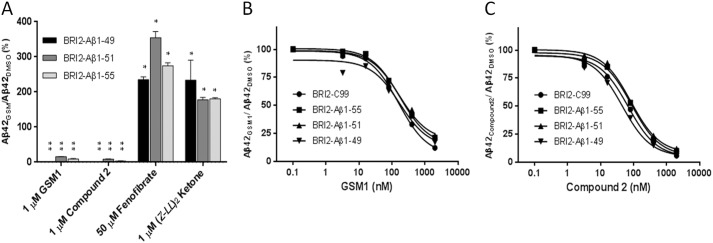

In contrast to the loss in potency for multiple GSIs, we found no evidence for differential effects of two potent GSMs (GSM1 and compound 2) and two inverse GSMs (fenofibrate and (Z-LL)2 ketone) on modulation of Aβ1–42 generation from cells expressing BRI2-Aβ1–49, 51, and 55 (Fig. 6A). Even though the yield of Aβx-42 from BRI2-Aβ49 was very low (5–10 pm, which is close to the detection limit of the ELISAs 1–2 pm), we were still be able to evaluate the modulation. At the concentrations used, all modulatory compounds showed a similar effect on Aβx-42 production as we had previously observed for APP or BRI-C99. The lack of differential modulation was further established by directly comparing the effect of varying concentrations of GSM1 (Fig. 6B) and compound 2 (Fig. 6C) on Aβx-42 production in CHO stable lines expressing BRI2-Aβ1–49, -Aβ1–51, and -Aβ1–55 and C99. No significant difference in dose response to these GSMs was observed.

FIGURE 6.

γ-Secretase cleavage of BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs can be modulated by GSMs. A, Aβx-42 levels from CHO stable line cells expressing the indicated BRI2-Aβ1-x vectors as measured by ELISA after treatment with 1 μm GSM1, 1 μm compound 2, 50 μm fenofibrate, or 1 μm (Z-LL)2 ketone were compared with the DMSO group. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. B and C, dose response of GSM1 (B) and compound 2 (C) on BRI2-C99 and BRI2-Aβ1-x constructs in CHO stable line cells is shown.

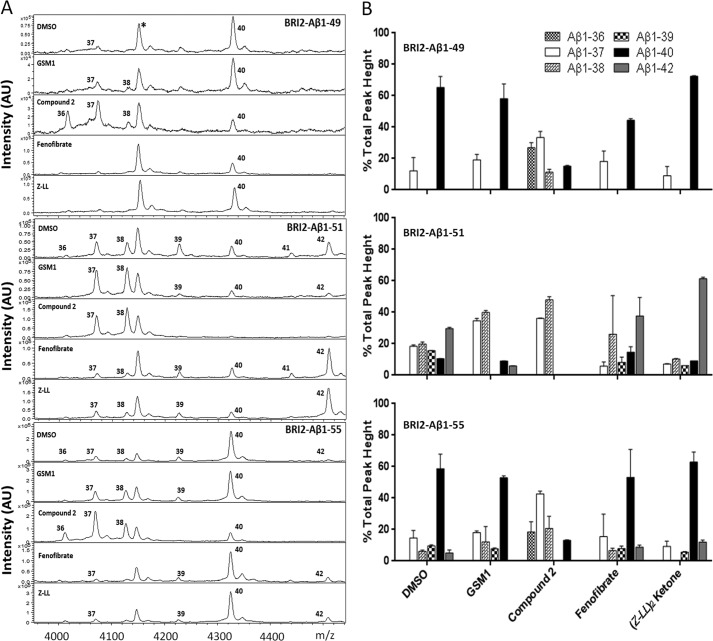

Because these BRI2-Aβ constructs were still sensitive to modulation, we used IP/MS to explore the changes in secreted Aβ profiles induced by GSM1, compound 2, fenofibrate, and (Z-LL)2 ketone from cells expressing BRI2-Aβ1–49, 1–51, and 1–55. Representative spectra from these studies are depicted in Fig. 7A, and the data are summarized in Fig. 7B. Studies of modulatory effects on BRI2-Aβ1–49 showed that GSM1 slightly increased relative levels Aβ1–37 and enabled the detection of Aβ1–38. Compound 2 dramatically shifted the spectra with large increases in Aβ1–36 and 1–37 noted and also a decrease in 1–40. In contrast, both iGSMs appeared to decrease the detection of shorter Aβ peptides but did not increase Aβ1–42. The effects of the compounds on the spectra from BRI2-Aβ1–51 were more dramatic; both GSM1 and compound 2 decreased Aβ1–39, 40, and 42 and increased Aβ1–37 and 38, although the effects of compound 2 were more dramatic in terms of reduction of Aβ1–39, 40, and 42. iGSMs decreased shorter Aβ levels and increased Aβ1–42. For BRI2-Aβ1–55, the results were similar to BRI2-Aβ1–51, but less dramatic for most compounds. GSM1 lowered Aβ1–42 and increased Aβ1–37 and 1–38. Compound 2 increased Aβ1–36, 37, and 38 and lowered Aβ1–39, 40, and 42. Both iGSMs increased the level of Aβ1–42.

FIGURE 7.

Mass spectra of Aβ from BRI2-Aβ1–49, 1–51, and 1–55 constructs in response to select GSMs. A, IP/MS spectra of conditioned media (1 ml) from CHO stable line cells expressing the indicated BRI2-Aβ1-x 49, 1–51, and 1–55 vectors treated with 1 μm GSM1, compound 2, μm (Z-LL)2 ketone, or 50 μm fenofibrate, respectively. *, peak at m/z 4150 is nonspecific. B, Aβ1-x production in the presence of GSMs. The sum of Aβ1–36 through Aβ1–42 peak intensities is assigned as 100%. Peaks with intensity of <5% or signal:noise ratio of <5 are not shown.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the precise mechanism by which γ-secretase generates different Aβ peptide species has both pathologic and therapeutic relevance. Our data, which use both ELISA and IP/MS methods to evaluate γ-secretase processing of Aβ1-x peptides ranging in length from 38 to 55 amino acids in cells, support and extend a number of recent studies demonstrating that stepwise cleavage by γ-secretase results in the generation of different Aβ1-x peptides (24, 27, 34–36). Although our data in general are consistent with the stepwise model of γ-secretase cleavage of APP along different product lines that preferentially produce Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42(34), they demonstrate a number of novel observations regarding the solubility of these long Aβ peptides and their processing by γ-secretase. First, we find that following transient transfection in HEK cells, all of the Aβ peptides are efficiently secreted as intact proteins that are soluble and easily detectable by IP/MS. Notably, both the long peptides derived from the BRI constructs and synthetic Aβ1–49 are quite stable in the media. This result is unexpected given that Aβs longer than Aβ1–42 have been reported to be difficult to detect by mass spectrometry and might be expected to be membrane-associated because they contain a portion of or the entire transmembrane domain of APP. Although we do detect full-length Aβ1–47 and Aβ1–48 secretion from the stable CHO cell lines, we do not detect longer full-length Aβ peptides. The reasons for this difference between the two different experimental paradigms is not clear at this time but perhaps might reflect subtle differences in membrane lipid composition influencing both γ-secretase processing and membrane binding; it has been shown that lipid composition can influence γ-secretase processivity (53). Because these long Aβ peptides are challenging to produce synthetically, the ability to produce soluble long Aβ peptides in HEK cells could be exploited as a source of standards for other biological studies. Second, although shorter Aβ peptides can be shown to be processed in vitro by detergent-solubilized γ-secretase, we find that in cells, peptides shorter than Aβ1–49 are not efficiently processed by γ-secretase; presumably they do not efficiently insert into intact non-detergent-solubilized membranes. In stable CHO cell lines, Aβ1–47 and 1–48 undergo very limited γ-secretase processing, most of the secreted peptides detected in these cells are the full-length peptides and not shorter Aβs. However, based on GSI inhibition studies, it does appear that the small amount of Aβ1–40 and 1–42 produced is generated by γ-secretase cleavage. In contrast, Aβ1–49 is efficiently cleaved in the stable CHO line to Aβ1–40 and 1–37. Third, although our data support the concept of product lines with the initial ϵ-cleavage generating Aβ1–49 cleavage primarily leading to Aβ1–40 and initial ϵ-cleavages at Aβ1–48 or 1–51 generating primarily Aβ1–42, it is clear that these product lines are not completely distinct. Aβ1–49 generates small amounts of Aβ1–42, detectable by ELISA; Aβ1–48 generates Aβ1–37 and small amounts of Aβ1–40 and 1–42; and Aβ1–51 generates Aβ peptides 1–37 to 1–42. Notably, the diversity of species generated from Aβ1–51 would suggest that when produced in cells, the stepwise cleavage is more heterogeneous than what is observed for Aβ1–49.

When BRI2-Aβ1–49 was co-transfected with either the M139V or Δexon9 PSEN1 mutants, neither altered the ratio of Aβ42:40 from BRI2-Aβ1–49. In the present study, M139V only increased Aβ42 from BRI2-C99 and BRI2-Aβ1–51 but not from BRI2-Aβ1–49. Although these data do not evaluate the effects on ϵ-cleavage, our data suggest that M139V and Δexon9 mutants alter Aβ42 by specifically inhibiting processivity by one cycle along the Aβ1–48/51 but not the Aβ1–49 production line. We would note that previous studies on M139V have led to different conclusions; a cell-free assay had shown that M139V does not alter ϵ-cleavage efficiency but does impair the fourth stepwise cleavage along both product lines when C99 was used as an in vitro substrate (36). In a separate report using a cell model, M139V increased Aβ42 but also reduced ϵ-cleavage efficiency (54). However, our present results are consistent with a previous study from our group where we found that the M139V mutant selectively raised Aβ42 but did not alter levels of other peptides in CHO cells stably overexpressing this mutant (55). Discrepancies between these results might be explained by the variable methodology, especially in cell culture systems where there are admixtures of wild-type and mutant PSEN1.

Another unexpected result from our study was the finding that the long Aβ peptides that are efficiently processed by γ-secretase in cells (e.g., Aβ1–49 to 1–55) are much less sensitive to inhibition by various GSIs. This loss of sensitivity to GSIs was observed in cells and in vitro using recombinant substrates. The basis for the differential sensitivity of these long Aβ peptides to GSI inhibition is not clear. However, given the rather dramatic effects observed, in some cases as much as a 300-fold differential sensitivity between Aβ1–49 and C99 in vitro, these data suggest that IC50 measures established for a GSI with any truncated substrate for γ-secretase could be misleading. This could be of importance when investigating effects of GSIs on other substrates; if one does not establish an IC50 for cleavage using a full-length substrate, such data could prove to be misleading. Indeed, some GSIs that have been reported to be “Notch-sparing” appear to have no substrate selectivity when evaluated using identical assay conditions in vitro (36, 56, 57).

In contrast to the differential sensitivity to GSIs, long Aβ peptides appear to remain sensitive to modulation of cleavage by both GSMs and iGSMs. Previous findings have shown that acidic (e.g., GSM1) and nonacidic GSMs (e.g., compound 2) have different modulatory effects. For the most part, acidic GSMs selectively lower Aβ1–42 and increase Aβ1–38, whereas nonacidic GSMs lower both Aβ1–40 and 1–42 and raise both Aβ1–37 and 1–38 (44, 58). Our current data provide some insight into the differences between these two GSM classes that are consistent with previous reports showing that GSMs enhance processivity by favoring an additional stepwise cleavage without altering the initial ϵ-cleavage event (49, 59, 60). Although both GSM1 and compound 2 reduce the small amount of Aβ1–42 that can be detected by ELISA, IP/MS studies demonstrate that compound 2 has a much larger effect on Aβ1–49 processivity, reducing Aβ1–40 and increasing Aβ1–36, 1–37, and 1–38. In contrast, both GSMs dramatically alter processivity from BRI2-Aβ1–51, increasing Aβ1–37 and 1–38 and lowering Aβ1–42. Although subtle, there does appear to be a stronger effect of compound 2 on reducing Aβ1–40. Although the effects of iGSMs on Aβ1–42 derived from Aβ1–49 were only detectable by ELISA, iGSMs showed a consistent effect on the three longer Aβ substrates decreasing the shorter Aβ peptides and increasing Aβ1–42. Overall these data suggest a model whereby the acidic GSMs preferentially enhance processivity along the Aβ1–42 product line, whereas nonacidic GSMs promote processivity along both Aβ1–40 and 1–42 product lines, with iGSMs decreasing processivity in both product lines.

Building on the pioneering work of Ihara and co-workers (24), multiple groups have now explored the mechanisms through which γ-secretase generates Aβ peptides with differing C termini. Using multiple different systems, ranging from homogenous purified reconstituted γ-secretase assays to cell culture studies, these studies provide detailed insights into how γ-secretase cleavage of APP generates Aβ peptides with differing C termini and how various factors such as mutations in APP, PSEN1/2, small molecules, or other factors can alter the profile of Aβ produced (35–37, 61). Although the data generated from the different systems is not identical, the differences for the most part are quantitative in nature and not qualitative. Through both heterogeneous ϵ-cleavage and differential stepwise processing, there can subtle to quite dramatic effects on the final profile of Aβ peptides produced. For example, several studies now show that FAD-linked mutations in APP and PSEN1 and PSEN2 alter γ-secretase by altering ϵ-cleavage site utilization, processivity, or some combination of these two mechanisms (35, 36). In contrast, the action of GSMs and iGSMs seems to be restricted to effects on processivity, with GSMs promoting additional stepwise cleavages and iGSMs partially inhibiting the stepwise cleavage (36). Further study of γ-secretase cleavage of other substrates and the effect of GSMs and iGSMs using methods such as those established here should provide additional data regarding whether the cleavage mechanism observed for APP is utilized for other substrates.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 AG 020206 and P01 AG025531 (to T. G.).

- Aβ

- amyloid β peptide

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- PSEN1

- presenilin 1

- BRI2

- integral membrane protein 2B

- IP/MS

- immunoprecipitation MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

- CHAPSO

- 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate

- GSI

- γ-secretase inhibitor

- GSM

- γ-secretase modulator

- iGSM

- inverse GSM

- CTF

- C-terminal fragment.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Golde T. E., Schneider L. S., Koo E. H. (2011) Anti-Aβ therapeutics in Alzheimer's disease. The need for a paradigm shift. Neuron 69, 203–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jack C. R., Jr., Knopman D. S., Jagust W. J., Shaw L. M., Aisen P. S., Weiner M. W., Petersen R. C., Trojanowski J. Q. (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 9, 119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holtzman D. M., Morris J. C., Goate A. M. (2011) Alzheimer's disease. The challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 77sr71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zou K., Liu J., Watanabe A., Hiraga S., Liu S., Tanabe C., Maeda T., Terayama Y., Takahashi S., Michikawa M., Komano H. (2013) Aβ43 is the earliest-depositing Aβ species in APP transgenic mouse brain and is converted to Aβ41 by two active domains of ACE. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 2322–2331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borchelt D. R., Thinakaran G., Eckman C. B., Lee M. K., Davenport F., Ratovitsky T., Prada C. M., Kim G., Seekins S., Yager D., Slunt H. H., Wang R., Seeger M., Levey A. I., Gandy S. E., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Price D. L., Younkin S. G., Sisodia S. S. (1996) Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Aβ1–42/1–40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 17, 1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scheuner D., Eckman C., Jensen M., Song X., Citron M., Suzuki N., Bird T. D., Hardy J., Hutton M., Kukull W., Larson E., Levy-Lahad E., Viitanen M., Peskind E., Poorkaj P., Schellenberg G., Tanzi R., Wasco W., Lannfelt L., Selkoe D., Younkin S. (1996) Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease [see comments]. Nat. Med. 2, 864–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suzuki N., Cheung T. T., Cai X.-D., Odaka A., Otvos L., Jr., Eckman C., Golde T. E., Younkin S. G. (1994) An increased percentage of long amyloid β protein is secreted by familial amyloid β protein precursor (βAPP717) mutants. Science 264, 1336–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jarrett J. T., Berger E. P., Lansbury P. T., Jr. (1993) The carboxy terminus of β amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation. Implications for pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry 32, 4693–4697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iwatsubo T., Odaka A., Suzuki N., Mizusawa H., Nukina N., Ihara Y. (1994) Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with and-specific Aβ monoclonals. Evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron 13, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Strooper B., Vassar R., Golde T. (2010) The secretases. Enzymes with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weidemann A., Paliga K., Dürrwang U., Reinhard F. B., Schuckert O., Evin G., Masters C. L. (1999) Proteolytic processing of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid precursor protein within its cytoplasmic domain by caspase-like proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5823–5829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lammich S., Kojro E., Postina R., Gilbert S., Pfeiffer R., Jasionowski M., Haass C., Fahrenholz F. (1999) Constitutive and regulated α-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3922–3927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Postina R., Schroeder A., Dewachter I., Bohl J., Schmitt U., Kojro E., Prinzen C., Endres K., Hiemke C., Blessing M., Flamez P., Dequenne A., Godaux E., van Leuven F., Fahrenholz F. (2004) A disintegrin-metalloproteinase prevents amyloid plaque formation and hippocampal defects in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1456–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asai M., Hattori C., Szabó B., Sasagawa N., Maruyama K., Tanuma S., Ishiura S. (2003) Putative function of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 as APP α-secretase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301, 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farzan M., Schnitzler C. E., Vasilieva N., Leung D., Choe H. (2000) BACE2, a β -secretase homolog, cleaves at the β site and within the amyloid-β region of the amyloid-β precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9712–9717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hussain I., Powell D., Howlett D. R., Tew D. G., Meek T. D., Chapman C., Gloger I. S., Murphy K. E., Southan C. D., Ryan D. M., Smith T. S., Simmons D. L., Walsh F. S., Dingwall C., Christie G. (1999) Identification of a Novel Aspartic Protease (Asp 2) as β-Secretase. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 14, 419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vassar R., Bennett B. D., Babu-Khan S., Kahn S., Mendiaz E. A., Denis P., Teplow D. B., Ross S., Amarante P., Loeloff R., Luo Y., Fisher S., Fuller J., Edenson S., Lile J., Jarosinski M. A., Biere A. L., Curran E., Burgess T., Louis J. C., Collins F., Treanor J., Rogers G., Citron M. (1999) β-Secretase celavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science 286, 735–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cai H., Wang Y., McCarthy D., Wen H., Borchelt D. R., Price D. L., Wong P. C. (2001) BACE1 is the major β-secretase for generation of Aβ peptides by neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 233–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolfe M. S., Kopan R. (2004) Intramembrane proteolysis. Theme and variations. Science 305, 1119–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Strooper B. (2003) Aph-1, Pen-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active γ-secretase complex. Neuron 38, 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu Y., Misonou H., Sato T., Dohmae N., Takio K., Ihara Y. (2001) Distinct intramembrane cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein family resembling γ-secretase-like cleavage of Notch. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35235–35238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sastre M., Steiner H., Fuchs K., Capell A., Multhaup G., Condron M. M., Teplow D. B., Haass C. (2001) Presenilin-dependent γ-secretase processing of β-amyloid precursor protein at a site corresponding to the S3 cleavage of Notch. EMBO Reports 2, 835–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takami M., Nagashima Y., Sano Y., Ishihara S., Morishima-Kawashima M., Funamoto S., Ihara Y. (2009) γ-Secretase. Successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of β-carboxyl terminal fragment. J. Neurosci. 29, 13042–13052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang R., Sweeney D., Gandy S. E., Sisodia S. S. (1996) The profile of soluble amyloid β protein in cultured cell media. Detection and quantification of amyloid β protein and variants by immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31894–31902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao G., Mao G., Tan J., Dong Y., Cui M. Z., Kim S. H., Xu X. (2004) Identification of a new presenilin-dependent zeta-cleavage site within the transmembrane domain of amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50647–50650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qi-Takahara Y., Morishima-Kawashima M., Tanimura Y., Dolios G., Hirotani N., Horikoshi Y., Kametani F., Maeda M., Saido T. C., Wang R., Ihara Y. (2005) Longer forms of amyloid β protein. Implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase. J. Neurosci. 25, 436–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yagishita S., Morishima-Kawashima M., Tanimura Y., Ishiura S., Ihara Y. (2006) DAPT-induced intracellular accumulations of longer amyloid β-proteins. Further implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase. Biochemistry 45, 3952–3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esh C., Patton L., Kalback W., Kokjohn T. A., Lopez J., Brune D., Newell A. J., Beach T., Schenk D., Games D., Paul S., Bales K., Ghetti B., Castaño E. M., Roher A. E. (2005) Altered APP processing in PDAPP (Val717 → Phe) transgenic mice yields extended-length Aβ peptides. Biochemistry 44, 13807–13819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukumori A., Okochi M., Tagami S., Jiang J., Itoh N., Nakayama T., Yanagida K., Ishizuka-Katsura Y., Morihara T., Kamino K., Tanaka T., Kudo T., Tanii H., Ikuta A., Haass C., Takeda M. (2006) Presenilin-dependent γ-secretase on plasma membrane and endosomes is functionally distinct. Biochemistry 45, 4907–4914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maddalena A. S., Papassotiropoulos A., Gonzalez-Agosti C., Signorell A., Hegi T., Pasch T., Nitsch R. M., Hock C. (2004) Cerebrospinal fluid profile of amyloid β peptides in patients with Alzheimer's disease determined by protein biochip technology. Neurodegener. Dis. 1, 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Portelius E., Dean R. A., Gustavsson M. K., Andreasson U., Zetterberg H., Siemers E., Blennow K. (2010) A novel Aβ isoform pattern in CSF reflects γ-secretase inhibition in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Portelius E., Van Broeck B., Andreasson U., Gustavsson M. K., Mercken M., Zetterberg H., Borghys H., Blennow K. (2010) Acute effect on the Aβ isoform pattern in CSF in response to γ-secretase modulator and inhibitor treatment in dogs. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21, 1005–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Funamoto S., Morishima-Kawashima M., Tanimura Y., Hirotani N., Saido T. C., Ihara Y. (2004) Truncated carboxyl-terminal fragments of β-amyloid precursor protein are processed to amyloid β-proteins 40 and 42. Biochemistry 43, 13532–13540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quintero-Monzon O., Martin M. M., Fernandez M. A., Cappello C. A., Krzysiak A. J., Osenkowski P., Wolfe M. S. (2011) Dissociation between the processivity and total activity of γ-secretase. Implications for the mechanism of Alzheimer's disease-causing presenilin mutations. Biochemistry 50, 9023–9035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chávez-Gutiérrez L., Bammens L., Benilova I., Vandersteen A., Benurwar M., Borgers M., Lismont S., Zhou L., Van Cleynenbreugel S., Esselmann H., Wiltfang J., Serneels L., Karran E., Gijsen H., Schymkowitz J., Rousseau F., Broersen K., De Strooper B. (2012) The mechanism of γ-secretase dysfunction in familial Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 31, 2261–2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okochi M., Tagami S., Yanagida K., Takami M., Kodama T. S., Mori K., Nakayama T., Ihara Y., Takeda M. (2013) γ-Secretase modulators and presenilin 1 mutants act differently on presenilin/γ-secretase function to cleave Aβ42 and Aβ43. Cell Reports 3, 42–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lewis P. A., Piper S., Baker M., Onstead L., Murphy M. P., Hardy J., Wang R., McGowan E., Golde T. E. (2001) Expression of BRI-amyloid β peptide fusion proteins. A novel method for specific high-level expression of amyloid β peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1537, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McGowan E., Pickford F., Kim J., Onstead L., Eriksen J., Yu C., Skipper L., Murphy M. P., Beard J., Das P., Jansen K., Delucia M., Lin W. L., Dolios G., Wang R., Eckman C. B., Dickson D. W., Hutton M., Hardy J., Golde T. (2005) Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 47, 191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim J., Onstead L., Randle S., Price R., Smithson L., Zwizinski C., Dickson D. W., Golde T., McGowan E. (2007) Aβ40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 627–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raymond C., Tom R., Perret S., Moussouami P., L'Abbé D., St-Laurent G., Durocher Y. (2011) A simplified polyethylenimine-mediated transfection process for large-scale and high-throughput applications. Methods 55, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murphy M. P., Hickman L. J., Eckman C. B., Uljon S. N., Wang R., Golde T. E. (1999) γ-Secretase, evidence for multiple proteolytic activities and influence of membrane positioning of substrate on generation of amyloid β peptides of varying length. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11914–11923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moore B. D., Chakrabarty P., Levites Y., Kukar T. L., Baine A. M., Moroni T., Ladd T. B., Das P., Dickson D. W., Golde T. E. (2012) Overlapping profiles of Aβ peptides in the Alzheimer's disease and pathological aging brains. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 4, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jung J. I., Ladd T. B., Kukar T., Price A. R., Moore B. D., Koo E. H., Golde T. E., Felsenstein K. M. (2013) Steroids as γ-secretase modulators. FASEB J. 27, 3775–3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Levites Y., Das P., Price R. W., Rochette M. J., Kostura L. A., McGowan E. M., Murphy M. P., Golde T. E. (2006) Anti-Aβ42- and anti-Aβ40-specific mAbs attenuate amyloid deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kimberly W. T., Esler W. P., Ye W., Ostaszewski B. L., Gao J., Diehl T., Selkoe D. J., Wolfe M. S. (2003) Notch and the amyloid precursor protein are cleaved by similar γ-secretase(s). Biochemistry 42, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fraering P. C., LaVoie M. J., Ye W., Ostaszewski B. L., Kimberly W. T., Selkoe D. J., Wolfe M. S. (2004) Detergent-dependent dissociation of active γ-secretase reveals an interaction between Pen-2 and PS1-NTF and offers a model for subunit organization within the complex. Biochemistry 43, 323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McGowan E., Pickford F., Kim J., Onstead L., Eriksen J., Yu C., Skipper L., Murphy M. P., Beard J., Das P., Jansen K., Delucia M., Lin W. L., Dolios G., Wang R., Eckman C. B., Dickson D. W., Hutton M., Hardy J., Golde T. (2005) Aβ42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 47, 191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kukar T. L., Ladd T. B., Robertson P., Pintchovski S. A., Moore B., Bann M. A., Ren Z., Jansen-West K., Malphrus K., Eggert S., Maruyama H., Cottrell B. A., Das P., Basi G. S., Koo E. H., Golde T. E. (2011) Lysine 624 of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a critical determinant of amyloid β peptide length. Support for a sequential model of γ-secretase intramembrane proteolysis and regulation by the amyloid β precursor protein (APP) juxtamembrane region. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39804–39812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tian G., Sobotka-Briner C. D., Zysk J., Liu X., Birr C., Sylvester M. A., Edwards P. D., Scott C. D., Greenberg B. D. (2002) Linear non-competitive inhibition of solubilized human γ-secretase by pepstatin A methylester, L685458, sulfonamides, and benzodiazepines. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31499–31505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Best J. D., Smith D. W., Reilly M. A., O'Donnell R., Lewis H. D., Ellis S., Wilkie N., Rosahl T. W., Laroque P. A., Boussiquet-Leroux C., Churcher I., Atack J. R., Harrison T., Shearman M. S. (2007) The novel γ secretase inhibitor N-[cis-4-[(4-chlorophenyl)sulfonyl]-4-(2,5-difluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]-1,1,1-trifl uoromethanesulfonamide (MRK-560) reduces amyloid plaque deposition without evidence of notch-related pathology in the Tg2576 mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320, 552–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fauq A. H., Simpson K., Maharvi G. M., Golde T., Das P. (2007) A multigram chemical synthesis of the γ-secretase inhibitor LY411575 and its diastereoisomers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17, 6392–6395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holmes O., Paturi S., Ye W., Wolfe M. S., Selkoe D. J. (2012) Effects of membrane lipids on the activity and processivity of purified γ-secretase. Biochemistry 51, 3565–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pinnix I., Ghiso J. A., Pappolla M. A., Sambamurti K. (2013) Major carboxyl terminal fragments generated by γ-secretase processing of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor are 50 and 51 amino acids long. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 21, 474–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Murphy M. P., Uljon S. N., Golde T. E., Wang R. (2002) FAD-linked mutations in presenilin 1 alter the length of Aβ peptides derived from βAPP transmembrane domain mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1586, 199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mayer S. C., Kreft A. F., Harrison B., Abou-Gharbia M., Antane M., Aschmies S., Atchison K., Chlenov M., Cole D. C., Comery T., Diamantidis G., Ellingboe J., Fan K., Galante R., Gonzales C., Ho D. M., Hoke M. E., Hu Y., Huryn D., Jain U., Jin M., Kremer K., Kubrak D., Lin M., Lu P., Magolda R., Martone R., Moore W., Oganesian A., Pangalos M. N., Porte A., Reinhart P., Resnick L., Riddell D. R., Sonnenberg-Reines J., Stock J. R., Sun S. C., Wagner E., Wang T., Woller K., Xu Z., Zaleska M. M., Zeldis J., Zhang M., Zhou H., Jacobsen J. S. (2008) Discovery of begacestat, a Notch-1-sparing γ-secretase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J. Med. Chem. 51, 7348–7351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crump C. J., Castro S. V., Wang F., Pozdnyakov N., Ballard T. E., Sisodia S. S., Bales K. R., Johnson D. S., Li Y. M. (2012) BMS-708,163 targets presenilin and lacks notch-sparing activity. Biochemistry 51, 7209–7211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Golde T. E., Koo E. H., Felsenstein K. M., Osborne B. A., Miele L. (2013) γ-Secretase inhibitors and modulators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 2898–2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weggen S., Eriksen J. L., Sagi S. A., Pietrzik C. U., Ozols V., Fauq A., Golde T. E., Koo E. H. (2003) Evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease amyloid β42 production by direct modulation of γ-secretase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31831–31837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sagi S. A., Lessard C. B., Winden K. D., Maruyama H., Koo J. C., Weggen S., Kukar T. L., Golde T. E., Koo E. H. (2011) Substrate sequence influences γ-secretase modulator activity, role of the transmembrane domain of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39794–39803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takami M., Funamoto S. (2012) γ-Secretase-dependent proteolysis of transmembrane domain of amyloid precursor protein. Successive tri- and tetrapeptide release in amyloid β-protein production. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 591392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]