Abstract

Background

Frailty, a multidimensional syndrome entailing loss of energy, physical ability, cognition, and health, plays a significant role in elderly morbidity and mortality. No study has examined frailty in relation to mortality after femoral neck fractures in elderly patients.

Questions/purposes

We examined the association of a modified frailty index abbreviated from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Frailty Index to 1- and 2-year mortality rates after a femoral neck fracture. Specifically we examined: (1) Is there an association of a modified frailty index with 1- and 2-year mortality rates in patients aged 60 years and older who sustain a low-energy femoral neck fracture? (2) Do the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves indicate that the modified frailty index can be a potential tool predictive of mortality and does a specific modified frailty index value demonstrate increased odds ratio for mortality? (3) Do any of the individual clinical deficits comprising the modified frailty index independently associate with mortality?

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 697 low-energy femoral neck fractures in patients aged 60 years and older at our Level I trauma center from 2005 to 2009. A total of 218 (31%) patients with high-energy or pathologic fracture, postoperative complication including infection or revision surgery, fracture of the contralateral hip, or missing documented mobility status were excluded. The remaining 481 patients, with a mean age of 81.2 years, were included. Mortality data were obtained from a state vital statistics department using date of birth and Social Security numbers. Statistical analysis included unequal variance t-test, Pearson correlation of age and frailty, ROC curves and area under the curve, Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics, and logistic regression models.

Results

One-year mortality analysis found the mean modified frailty index was higher in patients who died (4.6 ± 1.8) than in those who lived (3.0 ± 2; p < 0.001), which was maintained in a 2-year mortality analysis (4.4 ± 1.8 versus 3.0 ± 2; p < 0.001). In ROC analysis, the area under the curve was 0.74 and 0.72 for 1- and 2-year mortality, respectively. Patients with a modified frailty index of 4 or greater had an odds ratio of 4.97 for 1-year mortality and an odds ratio of 4.01 for 2-year mortality as compared with patients with less than 4. Logistic regression models demonstrated that the clinical deficits of mobility, respiratory, renal, malignancy, thyroid, and impaired cognition were independently associated with 1- and 2-year mortality.

Conclusions

Patients aged 60 years and older sustaining a femoral neck fracture, with a higher modified frailty index, had increased 1- and 2-year mortality rates, and the ROC analysis suggests that this tool may be predictive of mortality. Patients with a modified frailty index of 4 or greater have increased risk for mortality at 1 and 2 years. Clinical deficits of mobility, respiratory, renal, malignancy, thyroid, and impaired cognition also may be independently associated with mortality. The modified frailty index may be a useful tool in predicting mortality, guiding patient and family expectations and elucidating implant/surgery choices. Further prospective studies are necessary to strengthen the predictive power of the index.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, prognostic study. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Every year, the number of elderly, defined by the United Nations as people aged 60 years and older, is rising in the United States [24, 25] and is projected to be more than 50 million by 2015 [24]. Despite this increase in the elderly population, several studies have illustrated that overall incidence and age-adjusted rates of geriatric hip fractures in the United States for both men and women have declined in recent years [2, 9, 10, 23] secondary to improved functional ability, osteoporosis diagnosis and management, and improvements of the overall health in US populations [10, 23]. Increased awareness of healthier lifestyles and medical advancements have created a generation of more active and physiologically fit elderly [3, 6, 7]. Freedman et al. [7] demonstrated in a systematic review that prevalence of disability and functional limitations is declining among the US population, and Manton [14] concluded that chronic disability declined by 2.2% per year from 1999 to 2004. Consequently, an 80-year-old physically active patient may have more physiologic reserve to withstand the stresses of a femoral neck fracture than a deconditioned 80-year-old individual. With diverse disability and functional reserve among the US elderly, the idea of physiologic age and well-being may play an increasing role in mortality after a femoral neck fracture. Currently reported mortality rates may not account for diversity in physiologic function.

In this context, the term “frailty” refers to a multidimensional syndrome that includes a loss of reserves (energy, physical ability, cognition, health). Frail patients are more vulnerable to adverse outcomes, and a number of investigations have explored how frailty might account for some of the variability in health status as well as some of the differences in risk for adverse outcomes in similarly aged patients [3, 10, 23]. Frailty has been associated with morbidity and mortality in multiple settings. Frailty has been associated with short- and long-term all-cause mortality in hospitalized patients older than 64 years [17] and is an accessible tool for estimating individual risks of mortality [16]. In the surgical setting, frailty increases postoperative complications, institutional discharge, in-hospital mortality, and length of stay [14, 17, 23]. The idea of frailty has yet to be applied to mortality after elderly femoral neck fracture.

Studies have demonstrated this variability in physiologic reserve with a frailty index. Of particular interest is the frailty index developed by the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging is a prospective cohort study covering 5 years, initially developed to demonstrate the epidemiology of dementia and other important health issues in elderly Canadians. Through this initial analysis, the study group developed a frailty index measured by 70 prospectively assessed clinical deficits [1, 20]. Rockwood et al. [18, 19] demonstrated that patients with a higher frailty index had greater likelihood for death and institutionalization.

Few studies have examined predictive models for mortality after elderly femoral neck fracture. None have taken frailty into account. Our objective was to develop a modified frailty index, adapted and truncated from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, and demonstrate a relationship to femoral neck fracture mortality. Specifically we examined: (1) Is there an association of a modified frailty index with 1- and 2-year mortality rates in patients aged 60 years and older who sustain a low-energy femoral neck fracture? (2) Do the receiver operating curve (ROC) characteristics indicate that the modified frailty index can be a potential tool predictive of mortality and does a specific modified frailty index value demonstrate increased odds ratio for mortality? (3) Do any of the individual clinical deficits comprising the modified frailty index independently associate with mortality? We hypothesized that patients aged 60 years and older with a higher modified frailty index will have increased rates of mortality at both 1 and 2 years after low-energy femoral neck fracture.

Patients and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained before start of the study. All patients were treated at an American College of Surgeons-verified Level I trauma center. Medical records were queried for diagnosis and treatment codes associated with femoral neck fracture between the years 2005 and 2009. The codes used were International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision 820 and Current Procedural Terminology 27235, 27236, and 27132, resulting in 699 patients whom we considered for inclusion. The exclusion criteria included age younger than 60 years, fractures secondary to high-energy trauma or neoplasia, extracapsular hip fractures, previous proximal femur surgery on the side of injury, need for open reduction, or treatment other than closed reduction multiple cannulated screws, hemiarthroplasty, or THA. Fracture secondary to high-energy trauma was defined as a fracture from a motor vehicle accident, motorcycle accident, fall from a height, automobile versus pedestrian, or farm-related accident. Patients, who required revision surgery, had postoperative infection, or sustained a subsequent contralateral femoral neck fracture were further excluded. These patients were excluded secondary to concerns of bias from a possible increase in mortality from additional surgery for implant failure and infection or secondary injury from a contralateral femoral neck fracture. Patients without documented mobility status or use of assistive devices were excluded from the study because mobility, or ambulatory status, was part of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging frailty index; a total of 218 patients met one or more of the exclusion criteria, leaving 481 patients who were included in the study. The mean (± SD) age was 81.05 years (± 8.45 years) (range, 60–105 years; median, 82 years).

We reviewed the charts of the 481 patients who met our criteria. For each patient, date of surgery and age were recorded. From electronic medical records, the orthopaedic and/or medical history and physical notes at the time of fracture admission were used to obtain clinical deficits and calculate the modified frailty index. The modified frailty index was based on 19 of the potential 70 Canadian Study of Health and Aging clinical deficits (Table 1). Strong consensus among the authors was reached for the19 clinical deficits chosen. Deficits were stratified based on similarities in domain. The particular 19 deficits were chosen for two reasons. First, deficits were chosen based on the likelihood of being recorded in the admission notes. Second, keeping in mind the practical future application of the clinical deficits in an acute setting, the clinical deficits chosen could be assessed on admission or in the emergency department. Each deficit, except mobility status, was dichotomized. Zero points were given for the absence of a deficit and 1 point for its presence. Mobility status was trichotomized. Patients who were ambulatory without assistive devices received 0 points; patients who were ambulatory with a walker or cane received 1 point; and patients who were nonambulatory or wheelchair/scooter-dependent received 2 points. Therefore, there were a total of 19 clinical deficits with the potential for a maximum and minimum modified frailty index of 20 and 0, respectively. For example, a patient who has Parkinson’s disease and congestive heart failure and is functionally ambulatory with a walker would receive a modified frailty index of 3, the sum of clinical deficits. Mortality for each patient was obtained from the State Vital Statistics Department. Patients’ full names, Social Security numbers, and dates of birth were provided to obtain accurate death information. Patient death inquiries were provided for 2 years after fracture.

Table 1.

Modified frailty index clinical deficits

| Cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack |

| Impaired cognition (dementia, Alzheimer’s dementia) |

| History of recurrent falls |

| Diabetes mellitus (except diet-controlled) |

| History of syncope or blackouts |

| Ambulatory with no assistive devices or Ambulatory with walker or cane or Nonambulatory or use of scooter/wheelchair |

| Psychotic disorder (posttraumatic stress syndrome, bipolar disease, paranoia, schizophrenia) |

| Thyroid disease |

| History of seizures |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Depression |

| History of malignancy |

| Decubitus ulcers |

| Cardiac disease (coronary artery disease, arrhythmia mitral valve prolapse, aortic stenosis) |

| Urinary incontinence |

| Parkinson’s disease |

| Renal disease (acute or chronic) |

| Respiratory problems (COPD, emphysema, OSA, chronic bronchitis) |

| History of myocardial infarction |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

The following statistical analyses were performed.

Basic Analysis

The mean modified frailty index of those who died or lived within 1 and 2 years was compared using an unequal variance t-test. Percent mortality for each modified frailty index was calculated. The Pearson correlation of age and frailty index was computed. ROC curves were constructed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the frailty index in predicting 1- and 2-year mortality. Specifically, area under the curve (AUC) was computed. The point closest to perfect sensitivity and specificity was chosen as the cutoff value to compare mortality at 1 and 2 years. To further explore the calibration of the frailty index as a predictor for mortality, a logistic regression of mortality on the modified frailty index and computation of the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic were performed. Survival analysis comparing those with a modified frailty index above and below the cutoff value was performed.

Analysis of Validity and Robustness

We explored each clinical deficit as a dichotomous predictor of mortality at 1 and 2 years and computed a variety of metrics assessing accuracy. Next a logistic regression including all clinical deficits as predictors was analyzed with ROC analysis and Hosmer-Lemeshow. Our intention was to compare the roles of various clinical deficits with the results of the bivariate analyses directly. The coefficients derived for each regression allowed consideration of linear combinations of the clinical deficits. Because the ROC modified frailty index cutoff value chosen in the first step of our analysis is quite possibly overfitted, a 10-fold crossvalidation was performed while setting aside a separate validation set. In the crossvalidation we averaged the AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and concordance across the 10 folds. Finally, using all data but the test set, we built the modified frailty index, the associated ROC curve, computed the AUC, and picked that point on the ROC curve closest to perfect sensitivity and specificity. Using that value of the index, we examined the test set, computing sensitivity and specificity of the predictor on that set.

We assessed the impact of age on the discriminatory capability of the predictor by adding it to the logistic model containing all clinical deficits and comparing the Akaike information criteria of the models. We repeated these using a logistic model with age and modified frailty index only. Finally, to determine whether there was more than just one potential cutoff point impacting mortality, we carried out MARS regression with one, two, and three cut points on the index and mortality data. Data were jittered in order because not all frailty indices are round integers.

R software by the R Foundation for Statistical Computing (http://www.R-project.org) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

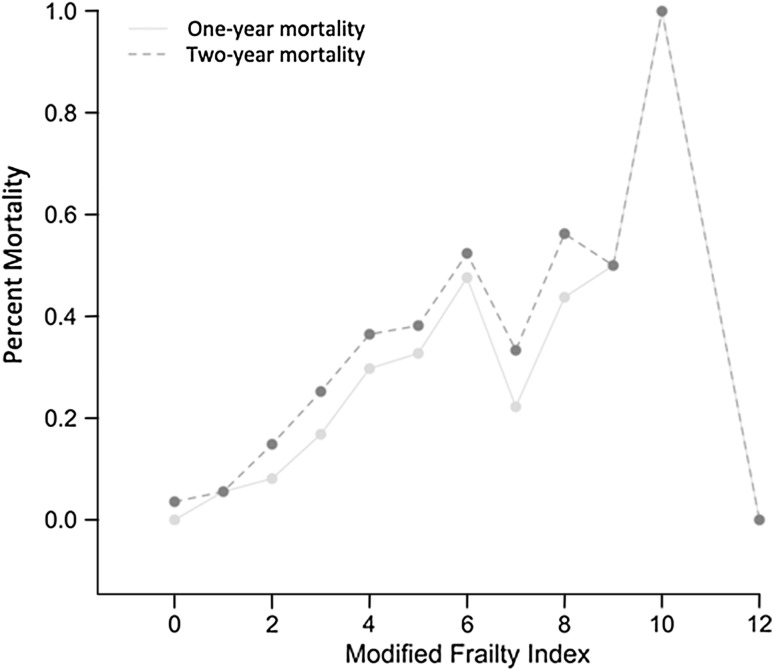

The modified frailty index was associated with 1- and 2-year mortality after a low-energy elderly femoral neck fracture. The 1-year mortality rate was 20.58% (99 of 481). The mean [SD] modified frailty index in those who died was higher (4.62 [1.83]) than in those who lived (2.98 [1.95]; p < 0.001). The 2-year mortality rate was 26.40% (127 of 481). The mean (SD) modified frailty index was 4.44 (1.87) and 2.91 (1.94) for patients who died and lived, respectively (p < 0.001). The distribution of frailty index was weighted toward the low end with 452 patients having a modified frailty index below and 29 patients having a modified frailty index equal to or greater than 7 (Table 2). Percent 1- and 2-year mortality increased for each rise in modified frailty index value up to 6 (Fig. 1). There was a weak but significant correlation between age and frailty (Pearson correlation 0.203, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Modified frailty index value table

| Modified frailty index value | Total number of patients |

|---|---|

| 0 | 28 |

| 1 | 72 |

| 2 | 74 |

| 3 | 107 |

| 4 | 74 |

| 5 | 55 |

| 6 | 42 |

| 7 | 9 |

| 8 | 16 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 12 | 1 |

Fig. 1.

The percent mortality for each modified frailty index. There is a direct relation between percent mortality and modified frailty index value initially. The variability after the modified frailty index > 6 is likely attributed to the fact that only 29 patients had a modified frailty index of ≥ 7.

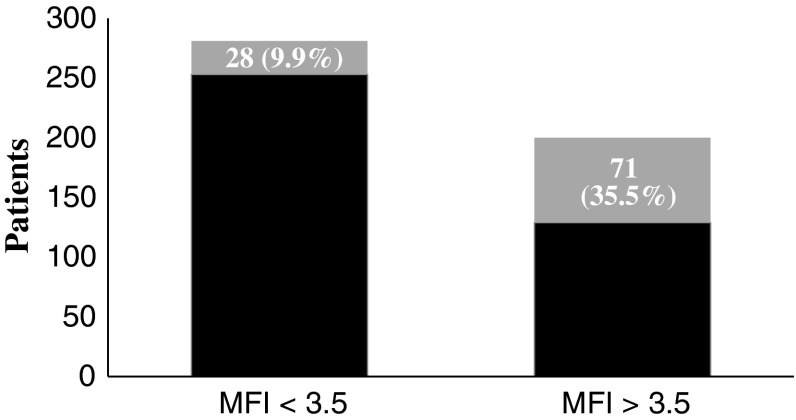

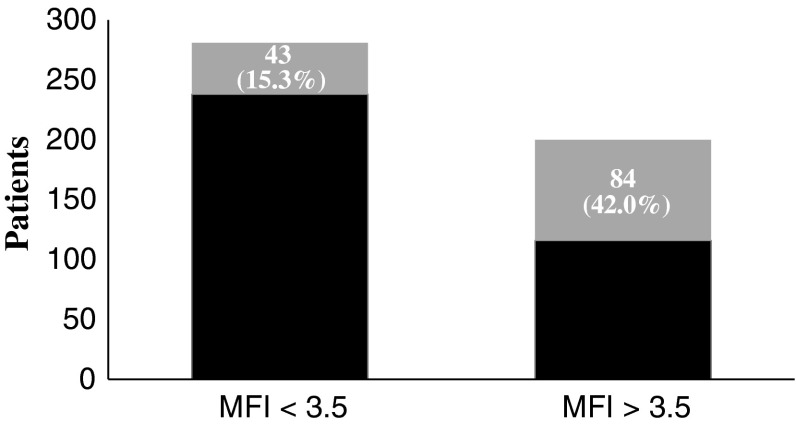

The modified frailty index predicts mortality both at 1 and 2 years after femoral neck fracture. The AUC was 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69–0.79) (0.72 [95% CI, 0.68–0.77]) for 1-year mortality [2-year mortality]. The point in the ROC curve with optimal sensitivity (0.72 [0.66]) and specificity (0.66 [0.67]) corresponded to a cutoff value of 3.5 (3.5). Applying this cutoff value, 9.96% (28 of 281) (43 of 281 [15.30%]) of patients below and 35.50% (71 of 200) (84 of 200 [42.00%]) of patients above the cutoff died (Figs. 2, 3). The odds ratio for death for patients above and below the cutoff value of 3.5 was 4.97 (3.06–8.09) (4.01 [2.61–6.16]) (Table 3). A chi-square test was significant (p < 0.001; p < 0.001) at both timeframes. The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was marginally significant (p = 0.046; p = 0.042), indicating the model may not be an optimal fit. Repeat analysis excluding all patients with frailty index above 7 demonstrated that the statistic was no longer significant with a p value of 0.74 (p = 0.58). Survival in those with frailty index less than 3.5 was estimated at 90.04% and 84.7% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. Survival in those with frailty index greater than 3.5 was estimated at 64.5% and 58% at 1 and 2 years, respectively.

Fig. 2.

One-year mortality for modified frailty index (MFI) stratified for < 3.5 and > 3.5. At 1 year, only 28 of 281 (9.96%) patients who had a MFI < 3.5 died as compared with 71 of 200 (35.5%) patients with a MFI > 3.5. Number of patients who died is represented by gray shading.

Fig. 3.

Two-year mortality for modified frailty index (MFI) stratified for < 3.5 and > 3.5. At 1 year, only 43 of 281 (15.3%) patients who had a MFI < 3.5 died as compared with 84 of 200 (42.0%) patients with a MFI > 3.5. Number of patients who died is represented by gray shading.

Table 3.

Odds ratio for death at 1 and 2 years with a modified frailty index ≥ 3.5

| Statistical measures | Modified frailty index ≥ 3.5 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | |

| Odds ratio for death | 4.97 (3.06–8.09) | 4.01 (2.61–6.16) |

| Sensitivity | 71.72% | 66.14% |

| Specificity | 66.23% | 67.23% |

| Overall concordance | 67.36% | 66.94% |

| Positive predictive value | 35.5% | 42% |

| Negative predictive value | 90.04% | 84.70% |

| Likelihood ratio (+) | 2.12 | 2.02 |

| Likelihood ratio (−) | 0.43 | 0.50 |

Patients with a modified frailty index ≥ 3.5 had an odds ratio of approximately 5 and 4 at 1 and 2 years, respectively.

Six deficits (mobility, respiratory, renal, malignancy, thyroid, and impaired cognition) were independently associated with mortality (Table 4) based on our logistic regression models. For 1-year mortality (2-year mortality), the ROC, based on the prediction of the regression, had an AUC of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.74–0.84) (0.77; 95% CI, 0.72–0.81). The point closest to the perfect sensitivity and specificity in the ROC curve had a sensitivity of 0.39 and specificity of 0.92 (sensitivity, 0.47; specificity, 0.86). With this cutoff value, there were 22 of 281 (7.83%) (42 of 301 [13.95%]) patients below and 77 of 200 (38.50%) (85 of 180 [47.22%]) patients above the cutoff who died. The odds ratio for death above and below the cutoff was 7.37 (5.52). A chi-square test was significant (p < 0.001; p < 0.001). The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was not significant (p = 0.096; p = 0.096), indicating relatively good model fit. No one clinical deficit, analyzed separately, was particularly sensitive (range, 5%–60%). However, the predictors are rather specific, and the rate of concordance was always above 50% and often greater than 70%. The positive predictive value was always below 50%, and the negative predictive value hovered around 80%. The largest likelihood ratio (+) was approximately 2.8, and the smallest likelihood ratio (−) was approximately 0.7 with some actually being greater than 1 (Table 2). Using a Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic on a logistic model for mortality with the sole predictor being mobility, we obtained a p value of 0.42 and 0.76 for 1- and 2-year mortality, respectively, indicating a relatively good model fit. Adding age to the full logistic regression model slightly improved the Akaike information criterion. The AUC in each case was changed by < 0.01. The Hosmer-Lemeshow fit improved for both 1- and 2-year mortality. Furthermore, the Net Reclassification Improvement was 0.20 and 0.25 for 1- and 2-year mortality, respectively, indicating that patient age is a potentially important prognostic factor. MARS regression was not particularly revelatory, showing patterns not reflective of the trends seen in the data. This was perhaps the result of the sudden drop in mortality at a frailty index of 7 or the precipitous drop at 12.

Table 4.

Results of statistical analysis evaluating logistic regression model for individual clinical deficits at 1- and 2-year mortality

| Year | Clinical deficits | Sensitivity | Specificity | Co-ncordance | PPV | NPV | Odds ratio | LR(+) | LR(−) | Full logistic OR | Full logistic p value |

Stepwise logistic OR | Stepwise logistic p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Respiratory: COPD, OSA, chronic bronchitis | 0.333 | 0.819 | 0.719 | 0.324 | 0.826 | 2.268 | 1.845 | 0.814 | 2.30E+00 | 0.00425 | 2.4 | 0.00166 |

| 2 | Respiratory: COPD, OSA, chronic bronchitis | 0.291 | 0.816 | 0.678 | 0.363 | 0.763 | 1.828 | 1.587 | 0.868 | 1.75 | 0.0419 | 1.97 | 0.00977 |

| 1 | Renal disease, acute or chronic | 0.232 | 0.887 | 0.753 | 0.348 | 0.817 | 2.386 | 2.064 | 0.865 | 1.9 | 0.0733 | 2.03 | 0.0321 |

| 2 | Renal disease, acute or chronic | 0.236 | 0.898 | 0.723 | 0.455 | 0.766 | 2.732 | 2.323 | 0.850 | 2.22 | 0.0159 | 2.37 | 0.00499 |

| 1 | Malignancy | 0.273 | 0.817 | 0.705 | 0.278 | 0.813 | 1.671 | 1.488 | 0.890 | 2.21 | 0.00813 | 2.03 | 0.0157 |

| 2 | Malignancy | 0.220 | 0.805 | 0.651 | 0.289 | 0.742 | 1.168 | 1.131 | 0.968 | 1.4 | 0.24 | ||

| 1 | Thyroid disease | 0.121 | 0.772 | 0.638 | 0.121 | 0.772 | 0.468 | 0.532 | 1.138 | 0.466 | 0.0377 | 0.46 | 0.0302 |

| 2 | Thyroid disease | 0.150 | 0.774 | 0.609 | 0.192 | 0.717 | 0.603 | 0.662 | 1.099 | 0.585 | 0.0856 | 0.607 | 0.0941 |

| 1 | Impaired cognition, dementia, delirium | 0.404 | 0.806 | 0.723 | 0.351 | 0.839 | 2.822 | 2.086 | 0.739 | 2.52 | 0.0012 | 2.55 | 0.000627 |

| 2 | Impaired cognition, dementia, delirium | 0.386 | 0.816 | 0.703 | 0.430 | 0.787 | 2.793 | 2.101 | 0.752 | 2.4 | 0.000942 | 2.51 | 0.000254 |

| 1 | Mobility > 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.96 | 0.000691 | 1.96 | 0.000265 |

| 2 | Mobility > 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.82 | .000936 | 1.92 | 0.000113 |

PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; LR = likelihood ratio; OR = odds ratio; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Discussion

As the growing elderly population continues to be more active and health-conscious, similarly aged patients may have significantly different physiologic reserves (frailty) to overcome the morbidity and mortality associated with a femoral neck fracture. As a result, frailty may play an important role in assessing patients with femoral neck fractures. Unfortunately, no study has examined the association of frailty with mortality after femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older. Our study demonstrates an association between a modified frailty index and 1- and 2-year mortality after femoral neck fracture, suggesting the potential to predict mortality. Patients with a modified frailty index of 4.0 or greater had higher odds ratio for mortality. Furthermore, independently, the clinical deficits of mobility, respiratory, renal, malignant, thyroid, and impaired cognition may be associated with mortality at 1 and 2 years.

This study had several limitations. First, the study was retrospective and therefore failure to properly document a clinical deficit in medical records is a concern; the patient’s medical history and physical notes may have been incomplete. It is possible that one or more deficits were missed that would have influenced the frailty index and affect the study results. To try to offset this, patients whose functional status was not documented were excluded from the study. Second, the 19 clinical deficits used to compute the modified frailty index have not been previously validated. However, they were obtained from a study clinically demonstrating the deficits associated with mortality. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging, from which these deficits were derived, was a highly powered prospective study with 10,263 patients. For each deficit examined in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, there were no more than 5% missing data [14]. Despite questions regarding validity, the ability to apply an abbreviated form of a high-powered index strongly correlated with mortality is necessary for clinical application and our study can be considered a pilot for future studies. Third, there is concern that the modified frailty index can potentially be overfitted and the predictive value may not be representative of other populations. However, the crossvalidation performed to further clarify this concern demonstrated an AUC for the test set of 0.74 and 0.72 for 1- and 2-year mortality, respectively. The application of the modified frailty index to other cohorts needs to be studied further.

Our findings demonstrate that the modified frailty index is associated with mortality at both 1 and 2 years after sustaining a femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older. Furthermore, there was an association for increasing risk of mortality with an increasing modified frailty index value (Fig. 1). This was demonstrated up to the modified frailty index of 7. The variability in mortality rate > 7 on the modified frailty index lacks a definitive conclusion as a result of the relatively low number of patients. There was a rather weak correlation (0.2) between age and frailty in our study, demonstrating that frailty is not solely determined by age. Several models of frailty index have been developed and have most commonly been used in a prospective, outpatient setting. Limited studies have evaluated patient frailty in the acute care setting. Farhat et al. [5] illustrated the association between frailty and mortality in patients older than 60 years who underwent emergency general surgical procedures. They demonstrated an odds ratio of 11 for mortality in patients with increased frailty. Elderly patients who died at 1 or 2 years after femoral neck fracture had a higher modified frailty index when compared with those who lived. Our results support the association of mortality and frailty demonstrated by other studies in multiple settings [12, 13, 21].

The modified frailty index appears to be a useful tool to predict mortality at 1 and 2 years status postfemoral neck fracture. The accuracy as demonstrated by the AUC was 0.74 and 0.72 for 1- and 2-year mortality, respectively. The association of both Charlson Comorbidity Index and American Society of Anesthesiologists score with mortality after femoral neck fractures has been studied [1, 4, 8, 11, 15, 18, 20, 22]. Unfortunately, these models do not take into account mobility status, a deficit that may independently be associated with mortality. Furthermore, frailty, by providing a detailed patient picture with 19 clinical deficits, may be more applicable to the physiologically varying elderly population. The ROC curve demonstrated a modified frailty index of 3.5 at 1 and 2 years with the best sensitivity and specificity. The odds ratio showed a fourfold likelihood for mortality in patients above a modified frailty index of 3.5 compared with those with a value below 3.5. Clinically, because we are unable to have half a clinical deficit, this value translates to having four or more clinical deficits. The sensitivity and specificity of 3.5 for predicting mortality was at best modest. However, the negative predictive value at 1 year was 90% and at 2 years was 84.7%. Patients with a modified frailty index below 3.5 have a significantly lower percent mortality at 1 and 2 years. This may ultimately impact implant choice. Patients with an index below 3.5 with survival of 90.0% and 84.7% at 1 and 2 years, respectively, may benefit more from a THA rather than hemiarthroplasty or percutaneous pinning. Consequently, the modified frailty index may not only be clinically relevant, but also impact the economics of health care. Patients with a higher modified frailty index would potentially benefit from admission to a medical service rather than to an orthopaedic service, improved nonopioid pain management, more aggressive physiotherapy, and/or more frequent postoperative visits with a primary care physician. The potential impact of the modified frailty index in clinical decision-making can be relevant to not only orthopaedics, but other specialties as well. Furthermore, the modified frailty index demonstrated signs of potential that can be applied in the acute setting as a relatively quick and easy predictive tool for mortality in patients with femoral neck fracture for not only orthopaedic surgeons, but for all treating physicians. Given the paucity of available mortality risk tools, the modified frailty index may help fill this void and initiate further advancement on the subject.

We found that the clinical deficits of mobility, respiratory, renal, malignancy, thyroid, and impaired cognition potentially are independently associated with mortality at 1 and 2 years (Table 4). The presence of any of these six clinical deficits may entail a poorer prognosis after a low-energy femoral neck fracture. The clinical deficits of mobility, respiratory (ie, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema), renal, malignancy, including any history of, and impaired cognition intuitively make sense in their potential to affect mortality; however, the correlation of thyroid disease to mortality is not as evident. Furthermore, although the association of age to frailty was weak, when age was added to the logistic regression model, there was improvement in the predictability of the modified frailty index slightly. Therefore, clinically, when comparing two patients with the same clinical deficits, increased age may be associated with greater likelihood for mortality. Furthermore, prospective studies are necessary to evaluate the influence of these six clinical deficits and the influence of age in the modified frailty index and mortality.

We found that considerable physiologic variability is present among elderly patients with femoral neck fracture. Awareness of this variability and studies examining predictive models for mortality accounting for this variability are necessary. A tool to measure frailty and potential prognostic implications for mortality in the acute setting would be beneficial, especially with the varying physiologic reserves encountered. We found the modified frailty index to be associated with mortality in patients aged 60 years and older with a femoral neck fracture at 1 and 2 years and may be a quick, easily applicable predictive model in the acute setting. We further found that patients with a value of 4 or more are at greater risk for mortality. Our data indicate that patients who have a modified frailty index with clinical deficits including mobility, respiratory, renal, malignancy, thyroid, and impaired cognition have a higher risk of death after femoral neck fracture. This modified frailty index warrants further exploration in a larger prospective study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adam Shar MD, Timothy Randell MD, and Zach Hubert BS, for their help with data collection.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group Canadian study of health and aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ. 1994;150:899–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chevalley T, Guilley E, Herrmann FR, Hoffmeyer P, Rapin CH, Rizzoli R. Incidence of hip fracture over a 10-year period (1991–2000): reversal of a secular trend. Bone. 2007;40:1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo Y, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA, Koval KJ. Gender differences in patients with hip fracture: a greater risk of morbidity and mortality in men. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:29–35. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, Horst HM, Swartz A, Patton JH, Jr, Rubinfeld IS. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as a predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1526–1530. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182542fab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: key indicators of well-being. 2010. Available at: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/main_site/default.aspx. Accessed July 24, 2013.

- 7.Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288:3137–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.24.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43:676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaglal SB, Weller I, Mamdani M, Hawker G, Kreder H, Jaakkimainen L, Adachi JD. Population trends in BMD testing, treatment, and hip and wrist fracture rates: are the hip fracture projections wrong? J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:898–905. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Vuori I, Järvinen M. Nationwide decline in incidence of hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1836–1838. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkland LL, Kashiwagi DT, Burton MC, Cha S, Varkey P. The Charlson Comorbidity Index Score as a predictor of 30-day mortality after hip fracture surgery. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:461–467. doi: 10.1177/1062860611402188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, Yip AM, Hirsch GM. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2010;121:973–978. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, Takenaga R, Devgan L, Holzmueller CG, Tian J, Fried LP. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manton KG. Recent declines in chronic disability in the elderly U.S. population: risk factors and future dynamics. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:91–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller CW. Survival and ambulation following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:930–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, MacKnight C, Rockwood K. The mortality rate as a function of accumulated deficits in a frailty index. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(02)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilotto A, Rengo F, Marchionni N, Sancarlo D, Fontana A, Panza F, Ferrucci L, FIRISIGG Study Group Comparing the prognostic accuracy for all-cause mortality of frailty instruments: a multicentre 1-year follow-up in hospitalized older patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockwood K, Song X, Mitnitski A. Changes in relative fitness and frailty across the adult lifespan: evidence from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. CMAJ. 2011;183:E487–E494. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C, McDowell I, Hébert R, Hogan DB. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353:205–206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04402-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Söderqvist A, Ekström W, Ponzer S, Pettersson H, Cederholm T, Dalén N, Hedström M, Tidermark J, Stockholm Hip Fracture Group Prediction of mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a two-year prospective study of 1,944 patients. Gerontology. 2009;55:496–504. doi: 10.1159/000230587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souza RC, Pinheiro RS, Coeli CM, Camargo KR., Jr The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) for adjustment of hip fracture mortality in the elderly: analysis of the importance of recording secondary diagnoses. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:315–322. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens JA. Anne Rudd R. Declining hip fracture rates in the United States. Age Ageing. 2010;39:500–503. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services. Administration on Aging. A profile of older Americans 2010: key indicators of well-being. Available at: http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/profile/2010/docs/2010profile.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2012.

- 25.World Population Ageing 2009. Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Population Division. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-population-ageing-2009.html. Accessed July 24, 2013.