Abstract

Background

Pseudotumors and immunologic alterations are reported in patients with elevated metal ion levels after resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. A direct association of increased cobalt and chromium concentrations with the development of pseudotumors has not been established.

Questions/purposes

We hypothesized that (1) patients with higher blood cobalt and chromium concentrations are more likely to have pseudotumors develop, (2) elevated cobalt and chromium concentrations correlate with increased activation of defined T cell populations, and (3) elevated metal ion levels, small implant size, cup inclination angle, and patient age are risk factors for the development of pseudotumors.

Methods

A single-surgeon cohort of 78 patients with 84 Articular Surface Replacement® implants was retrospectively investigated. Between 2006 and 2010, we performed 84 THAs using the Articular Surface Replacement® implant; this represented 2% (84/4950) of all primary hip replacements performed during that period. Of the procedures performed using this implant, we screened 77 patients (99%) at a mean of 43 months after surgery (range, 24–60 months). Seventy-one patients were investigated using ultrasound scanning, and cobalt and chromium concentrations in whole blood were determined by high-resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Differential analysis of lymphocyte subsets was performed by flow cytometry in 53 patients. Results of immunologic analyses were investigated separately for patients with and without pseudotumors. Pseudotumors were found in 25 hips (35%) and were more common in women than in men (p = 0.02). Multivariable regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors for the development of pseudotumors.

Results

Cobalt and chromium concentrations were greater in patients with pseudotumors than in those without (cobalt, median 8.3 versus median 1.0 μg/L, p < 0.001; chromium, median 5.9 versus median 1.3 μg/L, p < 0.001). The percentage of HLA-DR+CD4+ T cells was greater in patients with pseudotumors than in those without (p = 0.03), and the proportion of this lymphocyte subtype was positively correlated with cobalt concentrations (r = 0.3, p = 0.02). Multivariable regression analysis indicated that increasing cobalt levels were associated with the development of pseudotumors (p < 0.001), and that patients with larger implants were less likely to have them develop (p = 0.04); age and cup inclination were not risk factors.

Conclusions

We found a distinct association of elevated metal ion concentrations with the presence of pseudotumors and a correlation of increased cobalt concentrations with the proportion of activated T helper/regulator cells. Thus, the development of soft tissue masses after metal-on-metal arthroplasty could be accompanied by activation of T cells, indicating that this complication may be partly immunologically mediated. Further investigations of immunologic parameters in larger cohorts of patients with metal-on-metal arthroplasties are warranted.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The Articular Surface Replacement® (ASR™) Hip Resurfacing System (DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA) was withdrawn from the market owing to unacceptably high failure rates [10, 19, 28]. The ASR™ acetabular component, although stable [25], is subject to a greater amount of wear than other resurfacing devices [31], and high concentrations of cobalt and chromium ions in patients’ blood and urine have been reported after use of the ASR™ and other resurfacing devices [8, 20, 21]. The occurrence of pseudotumors is associated with increased wear of the femoral and acetabular resurfacing components, although pseudotumors also can be observed in the absence of excessive wear and in asymptomatic patients [2, 7, 12, 18, 24, 30]. The incidence of pseudotumors after metal-on-metal arthroplasties is reported to be as much as 39% to 59% [6, 16].

Increased metal ion concentrations seem to affect the immune system. A decrease in the number of circulating T helper cells in patients with elevated blood cobalt and chromium concentrations has been described after resurfacing arthroplasty [15]. Cobalt ions also exert a general depressive effect on T cells after insertion of the ASR™ device [26]. These findings that suggest a suppressive effect of metal ions on T cells are contrasted by reports of an increased activation of defined subsets of T cells and elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with elevated cobalt or chromium concentrations after metal-on-metal arthroplasties [13, 14].

An association between cobalt or chromium concentrations and the development of pseudotumors has been suggested [6, 20], although to our knowledge, the evidence that patients with pseudotumors have significantly greater metal ion levels is not strong. Moreover, the described immunologic alterations have not been correlated with the occurrence of pseudotumors, although an immunologic pathogenesis of these periarticular masses that are dominated by lymphocytic infiltrates seems highly probable [33].

We therefore hypothesized that (1) patients with pseudotumors have higher blood cobalt and chromium concentrations, (2) elevated cobalt and chromium concentrations correlate with increased activation of defined T cell populations, and (3) apart from metal ion concentrations the potential confounders of patient age, high cup inclination, and small implant size are risk factors for development of pseudotumors.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

Between 2006 and 2010, 84 resurfacing arthroplasties or large metal-bearing stemmed THAs using the ASR™ hip resurfacing system were performed by one surgeon (JM) in our department. Owing to a Medical Devices Alert (MDA/2010/069) issued in September 2010 by the British Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency [22], the use of this implant was abandoned by our department. Swedish guidelines for followup of patients who had received metal-on-metal implants of any kind were formulated in parallel with British recommendations [29]. Between 2006 and 2010, we performed 84 THAs using the ASR™; this represented 2% (84/4950) of all primary hip replacements performed during that period. For patients who had received the ASR™ implant, a specific followup program was designed on national and local levels. Briefly, all patients who had received this implant were invited for a clinical examination, analysis of blood cobalt and chromium ion levels, cross-sectional imaging including MRI or ultrasound, and analysis of leukocyte subsets. Approval by the local ethics committee was not required since the followup was performed in compliance with national recommendations for this group of patients identified as having a higher-than-average risk for implant failure.

Minimum followup was 2 years (mean, 3.6 years; range, 2–5 years). Eighty-four resurfacing arthroplasties or large metal-bearing THAs using the ASR™ implant were performed in 78 patients, consisting of 22 women and 56 men. Sixty-eight patients had an ASR™ resurfacing, and 10 had an ASR™ large metal-bearing combined with an uncemented stem. Ten patients had received bilateral resurfacing implants: six had an additional ASR™ implant, two had an Adept® (DePuy), one had a Durom® (Zimmer, Inc, Warsaw, IN, USA), and one had a Birmingham Hip™ Resurfacing System (BHR™; Smith & Nephew, Inc, Memphis, TN, USA) implanted on the contralateral side. Clinical followup and metal ion analysis were performed in 77 patients; only one patient was lost to followup. Ultrasound investigations were available for 71 patients; six patients declined further investigations because they were asymptomatic. Freshly drawn blood samples and immediate analysis at a specialized laboratory were required for lymphocyte subtyping and only a subset of 53 patients was available for this investigation.

Surgery

All surgeries were performed by one surgeon (JM) using the instruments and implants provided by DePuy. Patients were in a lateral decubitus position and a transgluteal approach was used. After incision of the joint capsule the femoral head was dislocated and exposed. After inserting the central guide pin in neutral or 10° valgus, debulking of the femoral head was performed using different reamers, after which a sheltering provisional femoral component was applied over the femoral head, which then was retracted posteriorly. Acetabular preparation and implantation of the uncemented ASR™ cup followed standard procedures. The definitive femoral prosthesis was fixed using high-viscosity cement (SmartSet® HV Cement; DePuy) that was injected into the cavity of the prosthesis. The implant then was positioned on the femoral head. Patients were allowed to mobilize using crutches, with partial weightbearing for 3 weeks, followed by full weightbearing as tolerated.

Ultrasound Scanning

The area surrounding the device (hip and acetabular regions via the lower abdomen) was scanned by an expert musculoskeletal radiologist (CL), specialized in ultrasound examinations with a Siemens-Acuson S2000™ ultrasound scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using either a 4C1 curved array transducer or a 9L4 linear array transducer depending on the body constitution of the subjects. Pseudotumors were identified as low or nonechogenic, well-defined lesions in the proximity of the implants. In compliance with a previous study [6], we defined a pseudotumor of the hip as a semisolid or cystic periprosthetic soft tissue mass that could not be attributed to an infection, malignancy, bursa, or scar tissue, regardless of its size. A thickened capsule was not considered a pseudotumour. The maximal size of the pseudotumors was measured in millimeters in two dimensions. MRI was not a part of the followup protocol and therefore was not systematically used.

Analysis of Ion Concentrations in Serum

Samples of whole blood were collected from patients in a standardized manner by a registered nurse. The containers used were 10-mL polypropylene tubes with sodium heparin (Teklab Ltd, Durham, UK). One batch of cannulas and tubes was used throughout the study. All materials used to collect and store samples were chosen for their lack of metals investigated in this study. Whole-blood samples subsequently were sent to an accredited external laboratory specializing in trace-metal analyses (ALS Scandinavica AB, Luleå, Sweden) and analyzed for concentrations of cobalt and chromium by high-resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry using a commercially available device (Element; Finnigan-MAT, Bremen, Germany). It was operated in medium-resolution mode, at m/μm 4200. The detection limits were 0.2 μg/L for chromium and 0.05 μg/L for cobalt. To facilitate comparison with a previous study [13], ion concentrations are presented as median concentrations in micrograms per liter.

Immunologic Analysis

Percentages and absolute counts of T, B, and natural killer (NK) lymphocyte populations, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, were analyzed on freshly drawn EDTA blood samples. Cells were stained with the BD Multitest™ 6-color TBNK reagent in BD Trucount™ tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). CD45-PerCP-Cy5.5 was used for gating on the lymphocyte population. CD3-FITC was used for identification of T cells, CD16 and CD56 PE for NK cells, CD4-PE-CY7 for T helper/inducer cells, CD8-APC-Cy7 for suppressor/cytotoxic T cells, and CD19-APC monoclonal antibody for B cells. Expression of the activation marker HLA-DR on CD4 and CD8 T cells was studied using a mixture of CD3-PE, CD4-FITC, CD8-APC, and HLA-DR-PE-CY7 (all from BD Biosciences). T cells were identified by gating on CD3+ and side scatter, and then CD4+ or CD8+ were gated and the percentage of HLA-DR expression on CD4+ and CD8+ cells was determined. The samples were analyzed on a BD FACSCanto™ with the BD FACSCanto™ and FACSDiva™ software (BD Biosciences). The mean total numbers or mean percentages of leukocytes and lymphocyte subsets (± two SDs) of 60 healthy blood donors served as references.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics used frequencies, means, 95% CIs, median values, ranges, Q-Q-plots, and the Shapiro-Wilks test of normality. Differences between categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test with Yates’ continuity correction where appropriate. The distributions of metal ion concentrations and some lymphocytic parameters (CD3+CD4+CD8+, DR+CD4+, DR+CD8+) were severely positively skewed, ie, most subjects were found at the lower ends of concentration ranges, contrasted by outliers with very high concentrations. These numerical variables therefore were investigated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction. Differences between normal distributed numerical variables were analyzed by the Welch two-sample t-test. By calculating the natural logarithms of nonnormal distributed variables, they were transformed to near-normal distributions, which was a prerequisite for performing parametric correlation and regression analyses. Correlation analyses of numerical variables were performed by calculating Pearson’s product momentum correlation coefficient r. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed after dichotomizing the patient population into patients who had pseudotumors develop and those who had not, and the independent covariates age, natural logarithm (Ln) of chromium concentration, implant size (treated as a numerical variable), and cup inclination angle were entered into the final model that was chosen on the basis of its high explanatory value. Exploratory models included additional covariates, but some regression coefficients were strongly correlated with each other and had to be omitted from the final model (such as a strong correlation of female sex and smaller implant size and the almost linear correlation of Ln cobalt with Ln chromium). Regression coefficients translating into risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs, Wald’s z scores, and p values were calculated. A ratio greater than 10 hips per covariate entered into the final regression model was ascertained. Akaike’s information criterion [27] and the adjusted R2 of the model according to Nagelkerke’s modification [27] were used to decide on the model with the best explanatory value. Model diagnostics included Cook’s distances and DfBetas, and there were no influential cases in the final model according to these criteria. Furthermore, standardized and studentized model residuals were calculated and less than 5% of all cases had residuals with absolute values larger than 2.

Two-tailed p values of 0.05 or less were considered significant. Based on previous data [13], we expected higher metal ion levels and higher percentages or numbers of certain lymphocyte subsets (DR+CD4+CD3+, DR+CD8+CD3+) in patients with pseudotumors, so in these analyses, one-tailed p values of 0.05 or less were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software package (Version 2.15.1; The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Clinical and Radiographic Characteristics of the Study Population

The mean age of the patients at surgery was 50.2 years (range, 22.6–68.3 years). Primary osteoarthritis was the underlying diagnosis in 62 (80%) hips, posttraumatic arthritis in four, dysplasia in three, rheumatoid arthritis in three, and osteochondritis in one.

The Harris hip score (HHS) was determined preoperatively and at followups by one physician (JM). For patients who had revision surgery, the HHS before the revision surgery was used in the statistical analyses. Followup included AP and lateral radiographs of the hip in all patients. The cup inclination angle in the frontal plane was measured against a horizontal reference line drawn along Köhler’s teardrop figures.

Preoperatively, the mean HHS of the entire cohort was 49 (range, 30–80). Postoperatively, the HHS had increased to a mean of 93 (range, 9–100). Patients with pseudotumors had a mean postoperative HHS of 90, which was lower when compared with the mean HHS of 99 in patients without pseudotumors (p = 0.01). Women and men did not differ in postoperative HHS (p = 0.98). Nine patients (nine hips) underwent revision surgery because of pain, symptomatic pseudotumors, loosening, or femoral neck fracture, and two additional patients (two hips) are scheduled for revision for the same reasons. Patients who had revision surgery had a mean HHS of 53 before revision compared with a mean of 100 in the group of patients who did not undergo revision surgery (p < 0.001). No dislocations or deep infections occurred.

Radiographic analyses showed a mean cup inclination angle of 48° (range, 38°–59°). Seventeen (22%) hips had a cup inclination angle greater than 50°. In 25 patients (35%), ultrasound scanning revealed the presence of pseudotumors near the implant. These lesions were found adjacent to the femoral neck, along the greater trochanter, or inside the pelvis. The extension of the lesions varied from 1 to 100 mm (median, 10 mm). Women were more likely to present with pseudotumors than men (Table 1) (p = 0.02), and pseudotumors were more frequent among patients who had revision surgery than among patients who did not have revision surgery (p = 0.02). Patients with pseudotumors had smaller implant sizes than those without (median 46/52 versus 51/58; p = 0.003). Patients with pseudotumors were slightly younger than those without (47.8 versus 51.6 years), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.2). There was no significant difference in cup inclination angle between patients with and without pseudotumors (mean 48° in both groups; p = 0.8).

Table 1.

Incidence of pseudotumors in women and men

| Sex | Pseudotumor | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Women | 7 | 11 |

| Men | 39 | 14 |

| p value (chi-square test) | 0.02 | |

Results

Metal Ion Levels and Development of Pseudotumors

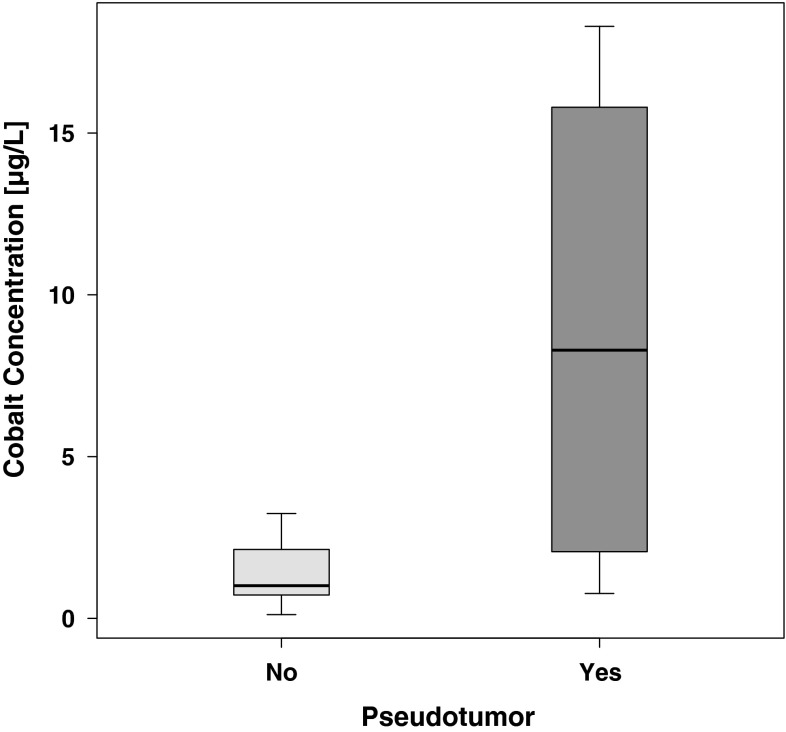

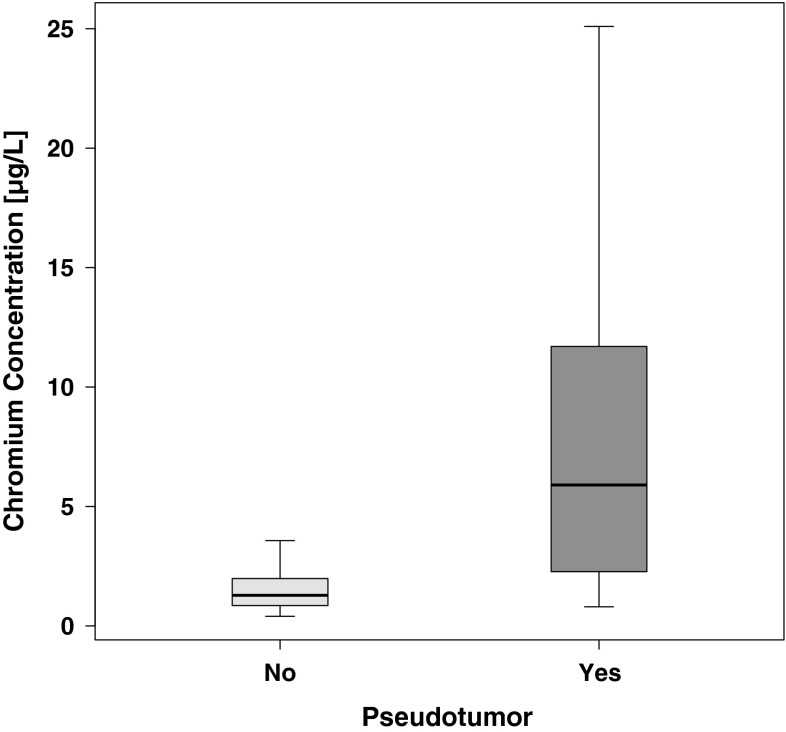

Blood cobalt and chromium concentrations were greater in patients with pseudotumors than in those without pseudotumors. The median whole-blood cobalt concentration in all subjects was 1.7 μg/L (range, 0.1–177.0 μg/L). The median whole-blood chromium concentration was 1.8 μg/L (range, 0.4–116.0 μg/L). Women had greater cobalt (2.7 versus 1.2 μg/L; p = 0.01) and chromium (3.3 versus 1.4 μg/L; p = 0.02) concentrations than men. Patients with pseudotumors had greater cobalt (8.3 versus 1.0 μg/L; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1) and chromium (5.9 versus 1.3 μg/L; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2) concentrations than patients without pseudotumors. Patients who had revision surgery had greater cobalt (35.7 versus 1.3 μg/L; p < 0.001) and chromium (15.2 versus 1.4 μg/L; p < 0.001) concentrations than patients who did not have revision surgery. A trend toward greater cobalt and chromium concentrations with increasing cup inclination angle was observed, but this observation failed to reach statistical significance (Pearson’s r = 0.15 for Ln cobalt, p = 0.2; Pearson’s r = 0.1 for Ln chromium, p = 0.4). There was no trend toward cobalt and chromium concentrations decreasing with time of exposure (Pearson’s r = −0.02 for Ln cobalt, p = 0.9; Pearson’s r = −0.04 for Ln chromium, p = 0.8).

Fig. 1.

A graph shows cobalt concentrations in patients with or without pseudotumors. Cobalt concentrations were significantly higher in patients with pseudotumors (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction). Outliers were removed from the graphic representation but not from statistical analysis.

Fig. 2.

A graph shows chromium concentrations in patients with or without pseudotumors. Chromium concentrations were significantly higher in patients with pseudotumors (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction). Outliers were removed from the graphic representation but not from statistical analysis.

Metal Ion Levels and T-cell Activation

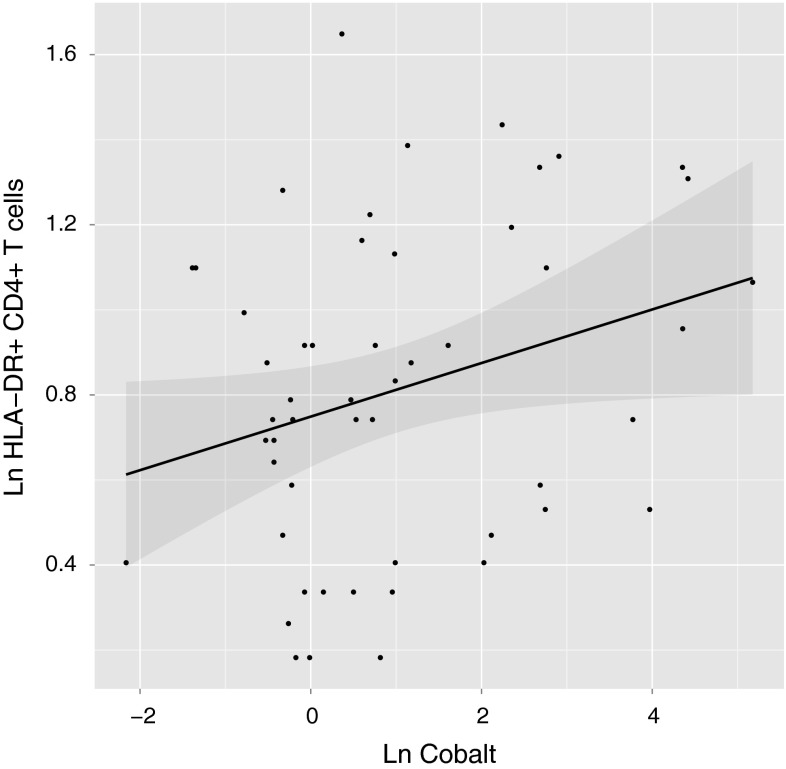

Patients with increased cobalt concentrations had a greater proportion of activated T cells. Comparison of lymphocyte subsets in patients with and without pseudotumors revealed that the percentage of DR+CD4+ T cells was greater in patients with pseudotumors than in those without, indicative of more pronounced activation of this specific subset of T cells in patients with pseudotumors (2.7% versus 2.3%; p = 0.03) (Table 2). Correlation analysis of white blood cell subsets showed that the proportion of DR+CD4+ T cells was positively correlated with cobalt concentrations (r = 0.3, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3). No other lymphocyte subset showed a statistically significant correlation with either metal ion, although there was a statistically nonsignificant trend toward a decreased total number of T cells with increasing cobalt and chromium concentrations (Table 3). The investigated cohort showed no gross abnormalities in their total number of white blood cells or in the absolute numbers and percentages of lymphocyte subsets. Most parameters were located in the normal range that was calculated based on a healthy reference population.

Table 2.

White blood cells and lymphocyte subsets in patients with or without pseudotumors

| Cell | Type | No Pseudotumor | Pseudotumor | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |||

| White blood cells | 6.35 | 5.82–6.89 | 6.67 | 5.82–7.53 | 0.5 | |

| T cells | CD3 | 72.2 | 69.5–74.9 | 71.4 | 67.8–75.0 | 0.7 |

| T helper cells | CD3CD4 | 42.8 | 40.0–45.6 | 46.8 | 42.1–51.4 | 0.1 |

| DR+ T helper cells | DRCD4 | 2.26 | 1.95–2.57 | 2.7 | 2.26–3.14 | 0.03 |

| T suppressor cells | CD3CD8 | 27.9 | 24.5–31.3 | 23.9 | 19.8–28.0 | 0.2 |

| DR+ T suppressor cells | DRCD8 | 2.34 | 1.62–3.05 | 2.39 | 1.61–3.18 | 0.4 |

| Ratio of helper/suppressor cells | CD4/CD8 ratio | 1.8 | 1.49–2.11 | 2.28 | 1.76–2.79 | 0.1 |

| B cells | CD19 | 11.3 | 9.21–13.47 | 11.4 | 9.52–13.3 | 0.96 |

| Natural killer cells | CD16CD56 | 15.3 | 13.0–17.6 | 16.2 | 12.2–20.3 | 0.7 |

* p values derived from Welch’s two-sample t-test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction for nonnormally distributed data.

Fig. 3.

A graph shows the relationship of DR+CD4+ T cells with cobalt concentrations. The dots designate individual measurements. The regression line is shown in black, with the surrounding 95% CI shaded. The logarithmically transformed proportion of HLA-DR+CD4+ T cells was positively correlated with logarithmically transformed cobalt concentrations (Pearson’s r = 0.3, p = 0.03). Ln = natural logarithm.

Table 3.

Correlation analyses of cobalt and chromium concentrations with lymphocyte subsets

| Variable | Type | Ln cobalt | Ln chromium | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r value* | p value | r value* | p value | ||

| Ln cobalt | 1.00 | NA | 0.92 | < 0.001 | |

| Ln chromium | 0.92 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | NA | |

| White blood cells | 0.22 | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.2 | |

| T cells | CD3 | −0.12 | 0.4 | −0.12 | 0.4 |

| T helper cells | CD3CD4 | 0.19 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.3 |

| DR+ T helper cells | Ln DRCD4 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| T suppressor cells | CD3CD8 | −0.23 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.1 |

| DR+ T suppressor cells | Ln DRCD8 | 0.01 | 1 | −0.02 | 1 |

| Ratio of helper/suppressor cells | CD4CD8 ratio | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| B cells | CD19 | 0.02 | 0.9 | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| Natural killer cells | CD16CD56 | 0.12 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.4 |

* Designates Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient; nonnormally distributed data were transformed to normality by calculating natural logarithms (designated “Ln”); NA = not applicable.

Risk Factors for the Development of Pseudotumors

Multivariable analysis was used to identify the adjusted risk of development of pseudotumors that was associated with cobalt levels, cup inclination angle, implant size, and patient age. Increasing cobalt concentrations were a risk factor of development of pseudotumors (p < 0.001). The risk of pseudotumors developing decreased with increasing implant sizes (p = 0.04). In this adjusted model, age and cup inclination angle exerted no statistically significant influence on the risk of development of pseudotumors (p > 0.05 for both covariates).

Discussion

Pseudotumors and immunologic alterations have been reported in patients with elevated metal ion levels after resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip [13, 15, 20, 21], but, to our knowledge, direct proof that patients with pseudotumors have greater metal ion concentrations in blood or urine than those without has not been presented. We therefore determined whether (1) patients with higher blood cobalt and chromium concentrations were more likely to have pseudotumors develop, (2) elevated cobalt and chromium concentrations correlated with increased activation of defined T cell populations, and (3) implant size, patient age, and cup inclination angle together with metal ion levels influenced the risk of development of pseudotumors. We found an association between increased blood cobalt and chromium concentrations and the occurrence of pseudotumors in patients with ASR™ implants. Furthermore, we found a correlation between cobalt concentrations and the proportion of activated T helper cells, and we identified elevated cobalt concentrations and small implant sizes as risk factors for the development of pseudotumors.

Weaknesses of our study include the retrospective design that precludes collection of relevant preoperative data such as metal ion concentrations or lymphocyte subsets before surgery and the loss of 24 patients to immunologic analysis. However, we believe the results from this exploratory study to be relevant, and future prospective studies using directed hypotheses can be based on the results described here. The hips in our cohort were investigated by ultrasound. The literature on the subject of pseudotumors after metal-on-metal arthroplasties is dominated by MRI investigations, but the use of ultrasound for detection of soft tissue masses after metal-on-metal arthroplasties is well established [34]. A recently proposed classification system of MRI findings resulted in moderate to good interobserver reliability [4], and it is suggested that MRI can predict the severity of tissue destruction around metal-on-metal arthroplasties [23]. However, MRI after hip arthroplasty often is hampered by imaging artifacts produced by adjacent metal implants, and these limitations do not apply to ultrasound. In addition, the use of ultrasound is explicitly proposed as an alternative to MRI in a national guideline on the structured followup of patients with metal-on-metal implants [29].We have no information regarding intraobserver or interobserver reliability of the ultrasound investigation used in our study, but there is no reason to believe that this should present a serious limitation, since an expert musculoskeletal radiologist with ultrasound scanning as a subspecialty performed all investigations in our study. The loss of six patients from the ultrasound protocol could introduce selection bias, but because this loss to followup is limited to less than 10% of all cases, we believe this effect to be negligible.

There is much literature describing elevated metal ion concentrations and the development of pseudotumors after hip resurfacing [20]. However, we believe our report is the first to describe that cobalt and chromium concentrations in patients with pseudotumors are significantly greater than in patients without pseudotumors. A previous study of patients who underwent metal-on-metal arthroplasties indicated that serum metal ion levels seemed to be greater in patients with pseudotumors than in those without, but the difference was small and not statistically significant [34]. In addition, some articles [20, 32] described elevated metal ion levels in patients with pseudotumors, but to our knowledge, without directly comparing this finding with metal ion concentrations in patients without pseudotumors.

Tissue reactions around loose orthopaedic implants are characterized by HLA DR+ macrophages and T cells at the bone-implant interface [3]. The neocapsule surrounding metal-on-metal implants contains CD3+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, and macrophages [9, 33, 37]. Intraosseous lymphocytic infiltrates also are found in the remnants of the femoral neck after failed resurfacing [37]. Taken together, available evidence indicates a massive involvement of the cellular immune response adjacent to failed resurfacing implants, with a predominance of HLA-DR+ macrophages and T cells. Conspicuously, we found a correlation between increasing cobalt concentrations and the proportion of HLA-DR+ T helper cells in our cohort which is partly in line with previously described findings [13]. At first glance, this finding of increased subpopulations of T cells in patients with elevated metal ion concentrations is in opposition to reports on decreasing numbers of T cells in general or T helper cells in patients with elevated metal ion concentrations [15, 26]. However, we report on a subtype of activated T cells that was not analyzed separately in the articles cited above. In fact, in accordance with Penny et al. [26], our material indicates that the total number of all T cells decreases with increasing cobalt concentrations. Cobalt and chromium are cytotoxic to primary human lymphocytes in vitro which may at least in part explain the depressive effects of metal ions on total T cell numbers [1]. The occurrence of HLA-DR antigens on T cells in our cohort may indicate an increased state of activation, but these T cells also could be anergic or regulatory [5, 11, 36]. It is tempting to speculate that sensitized and activated T cells are key players in the recruitment of lymphocytes to sites where metal debris is abundant, thus participating in the formation of pseudotumors, but further in vitro research is needed to elucidate the exact pathomechanisms.

We characterized risk factors for pseudotumor formation; apart form cobalt levels, which were discussed earlier, we found an inverse relationship between implant size and the formation of pseudotumors. Women have smaller implant sizes, in our cohort and in others, which may explain the higher incidence of pseudotumors and the increased risk of failure in women [20]. We found no association between age or cup inclination angle and pseudotumor formation which is in partial disagreement with the literature on this subject: steep acetabular component inclination angles have been described to be associated with greater amount of wear and greater metal ion levels in patient blood [17]. A multivariable regression analysis does not entirely rule out that certain parameters exert an influence on outcome, it merely describes that other parameters are of greater explanatory value when modeling the end point development of pseudotumors.

Pseudotumors are a common complication of metal-on-metal arthroplasties, and elevated metal ion concentrations in patient blood likewise are a common finding after such procedures [6, 13, 15, 20, 24]. An immunologic pathogenesis has been suspected since lymphocytic infiltrates characterize the histologic appearance of such pseudotumors, but the mechanisms underlying the development of the soft tissue masses are not well understood. This study on a cohort of 77 patients with the ASR™ device presents evidence of significantly elevated metal ion concentrations in the presence of pseudotumors, and our findings also suggest that an activation of certain T cell subtypes may be involved in this disorder. We believe that investigations of lymphocyte subsets in larger cohorts of patients with metal-on-metal arthroplasties could be of significant value to help us understand the pathophysiology of a relatively common consequence of this procedure, and immunohistochemical investigations of specimens retrieved at revision surgery should be performed. It remains to be seen whether screening for activated T-cells would help identify patients needing revision surgery, but in conjunction with the analysis of metal ion levels such tests could be of value. Since the cellular mechanisms underlying the phenomena observed in this study remain to be elucidated further, in vitro experiments need to be performed.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Akbar M, Brewer JM, Grant MH. Effect of chromium and cobalt ions on primary human lymphocytes in vitro. J Immunotoxicol. 2011;8:140–149. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2011.553845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almousa SA, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 March 28 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.al Saffar N, Revell PA. Interleukin-1 production by activated macrophages surrounding loosened orthopaedic implants: a potential role in osteolysis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Anderson H, Toms AP, Cahir JG, Goodwin RW, Wimhurst J, Nolan JF. Grading the severity of soft tissue changes associated with metal-on-metal hip replacements: reliability of an MR grading system. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:303–307. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baecher-Allan C, Wolf E, Hafler DA. MHC class II expression identifies functionally distinct human regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:4622–4631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosker BH, Ettema HB, Boomsma MF, Kollen BJ, Maas M, Verheyen CC. High incidence of pseudotumour formation after large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip replacement: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:755–761. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B6.28373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang EY, McAnally JL, Van Horne JR, Statum S, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Chung CB. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology. 2012;265:848–857. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniel J, Ziaee H, Pradhan C, McMinn DJ. Six-year results of a prospective study of metal ion levels in young patients with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:176–179. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies AP, Willert HG, Campbell PA, Learmonth ID, Case CP. An unusual lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in tissues around contemporary metal-on-metal joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:18–27. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:2287–2293. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans RL, Faldetta TJ, Humphreys RE, Pratt DM, Yunis EJ, Schlossman SF. Peripheral human T cells sensitized in mixed leukocyte culture synthesize and express Ia-like antigens. J Exp Med. 1978;148:1440–1445. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.5.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glyn-Jones S, Roques A, Taylor A, Kwon YM, McLardy-Smith P, Gill HS, Walter W, Tuke M, Murray D. The in vivo linear and volumetric wear of hip resurfacing implants revised for pseudotumor. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:2180–2188. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hailer NP, Blaheta RA, Dahlstrand H, Stark A. Elevation of circulating HLA DR(+) CD8(+) T-cells and correlation with chromium and cobalt concentrations 6 years after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:6–12. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.548028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallab NJ, Caicedo M, McAllister K, Skipor A, Amstutz H, Jacobs JJ. Asymptomatic prospective and retrospective cohorts with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty indicate acquired lymphocyte reactivity varies with metal ion levels on a group basis. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:173–182. doi: 10.1002/jor.22214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart AJ, Hester T, Sinclair K, Powell JJ, Goodship AE, Pele L, Fersht NL, Skinner J. The association between metal ions from hip resurfacing and reduced T-cell counts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:449–454. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD, Sabah SA, McRobbie D, Henckel J, Cobb JP, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:317–325. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart AJ, Skinner JA, Henckel J, Sampson B, Gordon F. Insufficient acetabular version increases blood metal ion levels after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2590–2597. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1930-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon YM, Glyn-Jones S, Simpson DJ, Kamali A, McLardy-Smith P, Gill HS, Murray DW. Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on-metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:356–361. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langton DJ, Joyce TJ, Jameson SS, Lord J, Van Orsouw M, Holland JP, Nargol AV, De Smet KA. Adverse reaction to metal debris following hip resurfacing: the influence of component type, orientation and volumetric wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:164–171. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B2.25099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langton DJ, Sidaginamale RP, Joyce TJ, Natu S, Blain P, Jefferson RD, Rushton S, Nargol AV. The clinical implications of elevated blood metal ion concentrations in asymptomatic patients with MoM hip resurfacings: a cohort study. BMJ open. 2013;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Langton DJ, Sprowson AP, Joyce TJ, Reed M, Carluke I, Partington P, Nargol AV. Blood metal ion concentrations after hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a comparative study of articular surface replacement and Birmingham Hip Resurfacing arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1287–1295. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B10.22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Medical Device Alert: ASR™ hip replacement implants manufactured by DePuy International Ltd (MDA/2010/069). Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Safetywarnings/MedicalDeviceAlerts/CON093789. Accessed September 16, 2013.

- 23.Nawabi DH, Gold S, Lyman S, Fields K, Padgett DE, Potter HG. MRI predicts ALVAL and tissue damage in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 January 26 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:847–851. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penny JO, Ding M, Varmarken JE, Ovesen O, Overgaard S. Early micromovement of the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) femoral component: two-year radiostereometry results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1344–1350. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B10.29030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penny JO, Varmarken JE, Ovesen O, Nielsen C, Overgaard S. Metal ion levels and lymphocyte counts: ASR hip resurfacing prosthesis vs. standard THA. Acta Orthop. 2013;84:130–137. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.784657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed September 17, 2013 (ISBN 3-900051-07-0).

- 28.Seppanen M, Makela K, Virolainen P, Remes V, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: short-term survivorship of 4,401 hips from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:207–213. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.693016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swedish Hip and Knee Society. [Monitoring of metal-on-metal prostheses in Sweden][in Swedish]. Available at: http://www.ortopedi.se/pics/6/59/Ytis_riktlinjer_120516001.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2013.

- 30.Toms AP, Marshall TJ, Cahir J, Darrah C, Nolan J, Donell ST, Barker T, Tucker JK. MRI of early symptomatic metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective review of radiological findings in 20 hips. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Underwood R, Matthies A, Cann P, Skinner JA, Hart AJ. A comparison of explanted Articular Surface Replacement and Birmingham Hip Resurfacing components. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:1169–1177. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Weegen W, Smolders JM, Sijbesma T, Hoekstra HJ, Brakel K, van Susante JL. High incidence of pseudotumours after hip resurfacing even in low risk patients; results from an intensified MRI screening protocol. Hip Int. 2013;23:243–249. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Koster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints: a clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:28–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.A.02039pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DH, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. Prevalence of pseudotumor in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:2164–2171. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witzleb WC, Hanisch U, Kolar N, Krummenauer F, Guenther KP. Neo-capsule tissue reactions in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:211–220. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu P, Fu YX. Tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes: friends or foes? Lab Invest. 2006;86:231–245. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zustin J, Amling M, Krause M, Breer S, Hahn M, Morlock MM, Ruther W, Sauter G. Intraosseous lymphocytic infiltrates after hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a histopathological study on 181 retrieved femoral remnants. Virchows Archiv. 2009;454:581–588. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0745-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]