Abstract

Background/Aims

We investigated the efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-based treatment in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who failed previous antiviral therapies.

Methods

Seventeen patients who failed to achieve virological responses during sequential antiviral treatments were included. The patients were treated with TDF monotherapy (four patients) or a combination of TDF and lamivudine (13 patients) for a median of 42 months. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) were measured, and renal function was also monitored.

Results

Prior to TDF therapy, 180 M, 204 I/V/S, 181 T/V, 236 T, and 184 L mutations were detected. After TDF therapy, the median HBV DNA level decreased from 4.6 log10 IU/mL to 2.0 log10 IU/mL and to 1.6 log10 IU/mL at 12 and 24 months, respectively. HBV DNA became undetectable (≤20 IU/mL) in 14.3%, 41.7%, and 100% of patients after 12, 24, and 48 months of treatment, respectively. HBeAg loss was observed in two patients. Viral breakthrough occurred in five patients who had skipped their medication. No significant changes in renal function were observed.

Conclusions

TDF-based rescue treatment is effective in reducing HBV DNA levels and is safe for patients with CHB who failed prior antiviral treatments. Patients' adherence to medication is related to viral rebound.

Keywords: Antiviral agents, Treatment outcome, Hepatitis B, Resistance, Tenofovir

INTRODUCTION

The aim of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) treatment is to improve quality of life and prevent progression to cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma.1,2 Long-term anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) nucleos(t)ide therapy is effective in prevention of progression of liver disease. Lamivudine (LAM) and adefovir (ADV) have been used for antiviral treatment of CHB patients and showed potent viral suppression and histologic improvement.3,4 However, long-term use of nucleos(t)ide analogue inevitably leads to the development of resistant HBV mutants and viral breakthrough.5 Genotypic resistance can be detected in 60% to 70% after 5 years of LAM treatment6 and in 20% to 29% after 5 years of ADV treatment.7 The treatment options for patients who fail LAM and ADV monotherapy have been limited. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), the oral prodrug of tenofovir, is a nucleotide analogue with potent activity against HBV DNA polymerase and shows potent antiviral activity in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative and HBeAg-positive CHB naïve patients.8 There are few studies about the virological response and safety of long-term use of TDF in nucleos(t)ide analogue experienced-patients with multidrug resistant HBV or suboptimal response. TDF safe and effective in patients with prior failure of LAM and in patients with suboptimal response to ADV or entecavir (ETV) therapy.9,10 The combination of ETV and TDF is highly efficient and safe in patients with partial responses to preceding therapies.11 However, long-term data of efficacy and safety of TDF in treatment-experienced patients is not sufficient.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the antiviral efficacy and safety of TDF-based antiviral treatment in CHB patients with suboptimal response to previous antiviral therapy or multidrug resistant patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

From May 2006 to July 2012, 17 CHB patients with partial virological response to previous antiviral therapy or multidrug resistance who were treated with TDF subsequently were included at three centers in Seoul and Incheon, Korea. All patients had taken sequential treatment with antiviral agents for LAM resistance and had been compliant with the regimen. None of the patients were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus. For the rescue therapy for suboptimal response of HBV resistance to the sequential treatment, four patients received TDF monotherapy (300 mg/day) and 13 patients received TDF (300 mg/day) and LAM (100 mg/day) combination therapy more than 6 months by clinicians' choice. TDF was not available in Korea through the study period. The patients were able to get the medicine for salvage therapy at Korea Orphan Drug Center.

Partial virological response was defined as a decrease in HBV DNA of more than 1 log10 copies/mL but dectable HBV DNA after 6 or 12 months of antiviral therapy in compliant patients.1 Virological breakthrough was defined as more than 1 log10 copies/mL increase in HBV DNA level from nadir.2

Serial sera were collected from each patient at the time of baseline and every 6 months during treatment, or at the time of viral breakthrough and stored frozen at -80℃ for test of antiviral resistant mutation of HBV. Written informed consent for the collection of serum samples was obtained from the patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Konkuk University Medical Center and was conducted in accord with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

2. Clinical and laboratory assessments

Laboratory data including serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, bilirubin, creatinine, creatinine clearance, and HBV DNA, HBeAg, anti-HBe were measured at baseline and every 3 months after the antiviral treatment. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was measured every 1 year of the treatment.

Serum HBV DNA levels were assessed using COBAS Amplicor polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (lower limit of detection of 20 IU/mL; Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA).

3. Efficacy and safety

Virological responses were evaluated by median change in HBV DNA load from baseline, the proportion of patients achieving a viral load <20 IU/mL (120 copies/mL), HBeAg and HBsAg loss and seroconversion. Changes of median serum ALT level were also evaluated.

Safety and tolerability were assessed from renal function and hepatic decompensation. Renal function abnormality was defined as an increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.5 mg/dL above the baseline value on two consecutive occasions.

4. Detection of antiviral-resistant mutations

When a viral breakthrough developed during the treatment period, we checked for compliance and tested a restriction fragment mass polymorphism (RFMP; Genematrix, Youngin, Korea) to identify LAM (rt204, rt180), ADV (rt181, rt236), and ETV (rt184, rt202, rt250) resistant mutations of HBV polymerase gene.5 The RFMP assay can detect 100 copies of HBV genome per milliliter.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics of the patients

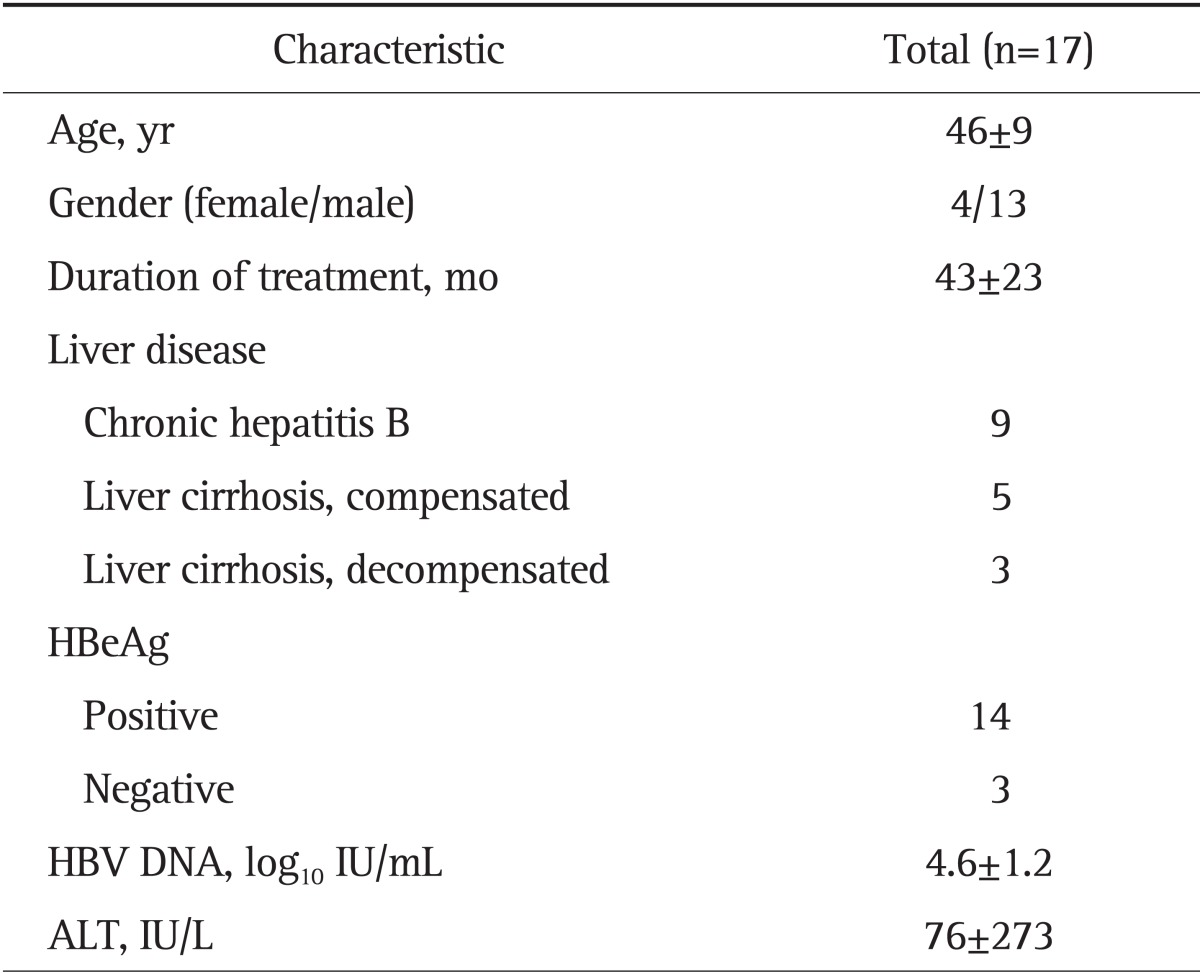

The baseline characteristics of the 17 patients are summarized in Table 1. The median follow-up during TDF or TDF and LAM combination treatment was 42 months (range, 12 to 72 months). Eight patients had liver cirrhosis, and three of them had decompensated liver cirrhosis. Fourteen patients were HBeAg positive, and median HBV DNA level prior to TDF based treatment was 4.6 log10 IU/mL. Median ALT level was 76 IU/L (range, 23 to 1,068 IU/L).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Demographics and Characteristics

Data are presented as mean±SD or number.

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

2. Previous antiviral treatment and resistance mutations

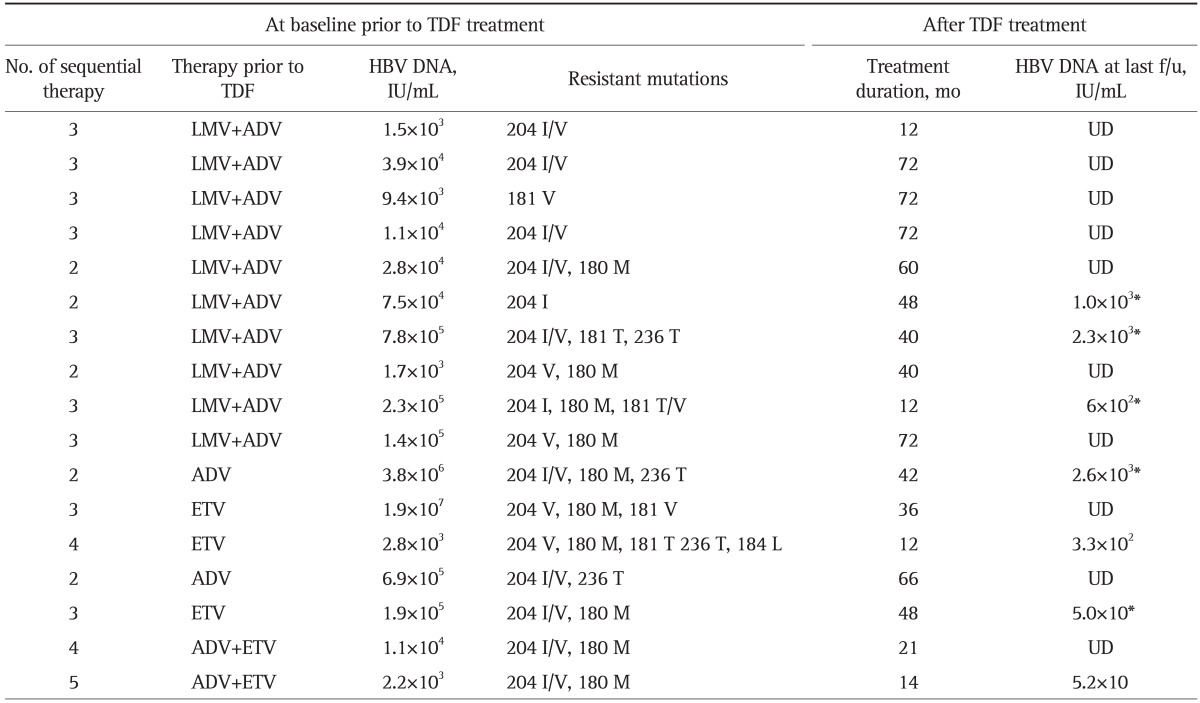

All patients had been treated with LAM as a first line oral antiviral agent and second line antiviral treatments for LAM resistance subsequently. Prior to TDF base treatment, 10 patients were treated with LAM and ADV combination therapy and the other seven patients were treated with ADV or ETV monotherapy or ADV and ETV combination therapy. The patterns of baseline polymerase sequence mutations conferring antiviral resistance in the patients are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Previous Antiviral Agents and Genotypic Mutations

TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; HBV, hepatitis B virus; f/u, follow-up; LMV, lamivudine; ADV, adefovir; UD, undetectable; ETV, entecavir.

*Patients with poor compliance.

3. Efficacy

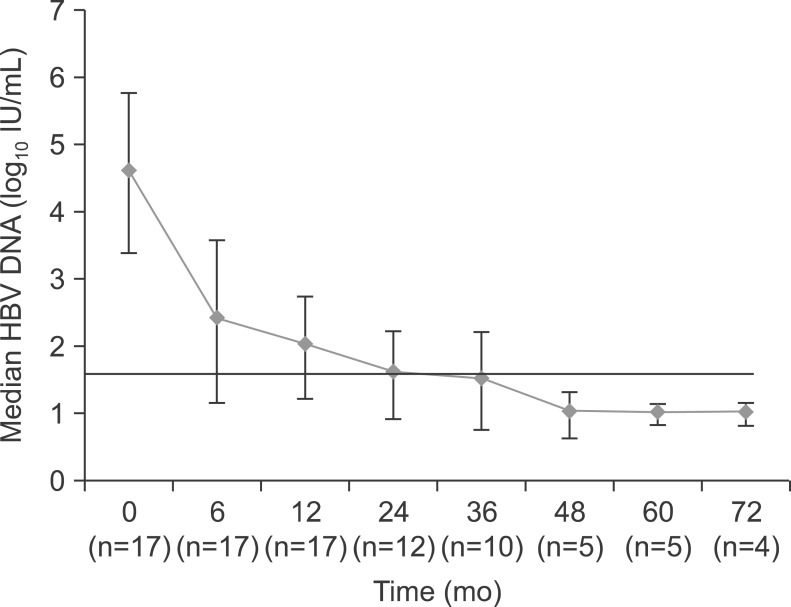

The change in median level of HBV DNA of the patients is shown in Fig. 1. The median decrease in the HBV DNA level from baseline to 12 month was 2.6 log10 IU/mL. The decrease in viral load continued to 3.0 log10 IU/mL at 24 months. At 6 months of starting the TDF based treatment, HBV DNA levels became undetectable in two patients. Two of 14 (14.3%) and five of 12 patients (41.7%) achieved an undetectable viral load at 12 and 24 months of the therapy, respectively. HBV DNA was undetectable in five patients at 48 months of follow-up and in four patients at 72 months of follow-up (Table 2). One of the 17 patients showed primary nonresponse to the TDF treatment, but HBV DNA was undetectable after 24 months after start of TDF in the patient. During the follow-up period, viral breakthrough occurred in five patients with skipping of their medication; however, it was not observed in patients with good compliance. Genotypic analysis was available in two of them. No significant resistant mutations were detected. HBV DNA decreased after restart of the treatment. Elevation in serum bilirubin and ALT level accompanied with the viral rebound was observed in a patient within 1 month of discontinuation. However, no patients with virological breakthrough showed hepatic decompensation.

Fig. 1.

Median changes in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-DNA during the tenofovir-based rescue therapy.

HBeAg loss was observed in two out of 14 HBeAg positive patients (14.2%) after a treatment duration of 42 and 60 months, respectively. HBeAg seroconversion or HBsAg loss did not occurred.

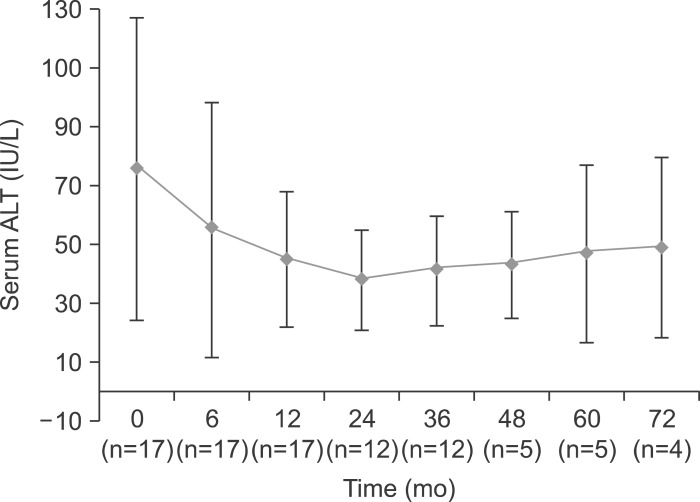

Median ALT level decreased during the course of the study from 76 IU/L at baseline to 38 IU/L at 24 months of the treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Median changes in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) during the tenofovir-based rescue therapy.

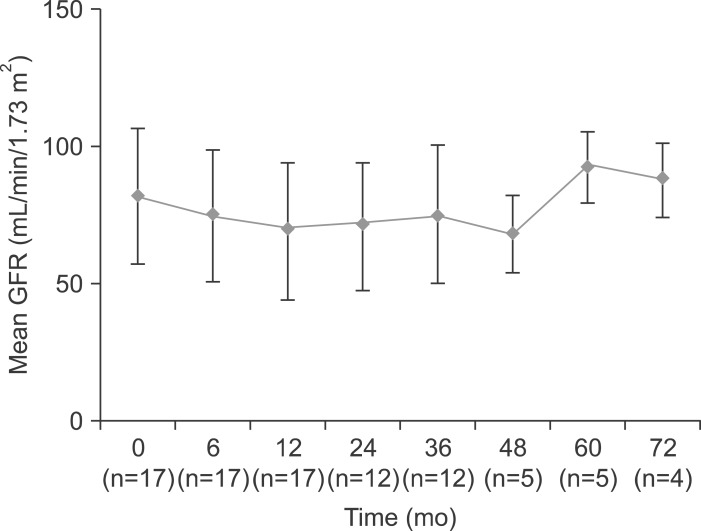

4. Safety

There were no significant clinical adverse events during the TDF based treatment. Mean creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate revealed no significant change during the treatment period (Fig. 3). No patient developed treatment induced renal impairment (rise of more than 0.5 mg/dL in serum creatinine level from baseline). Renal function was maintained well in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. In two patients, serum creatinine values were already elevated at baseline (1.4 mg/dL) and remained stable during the treatment period. One patient with pre-existing severe renal impairment (serum creatinine, 4.6 mg/dL) was treated with a reduced dose of TDF and showed no increase in creatinine level.

Fig. 3.

Change in the mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) during the tenofovir-based rescue therapy.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that TDF based rescue treatment potently suppresses HBV replication in CHB patients with suboptimal response to previous antiviral therapy or multidrug-resistant mutations.

Sequential nucleos(t)ide monotherapy or combination treatment has been used for treatment of CHB patients with antiviral resistance. The sequential treatments promote the selection of multidrug-resistant mutations. ADV was used for second line treatment of LAM resistant patient, however, ADV resistance and viral breakthrough occurred frequently.12,13 ADV and LAM combination therapy reduces the development of ADV resistance and has been a practical option for treatment of LAM resistance.14 However, the antiviral efficacy of ADV and LAM combination was not satisfactory.

All patients studied in this study were treated with LAM for the first line oral antiviral agent, a popularly used nucleoside analogue in Korea. LAM has potent antiviral effects, but long-term use of this drug induces a genotypic resistance of HBV and viral breakthrough.6 The patients developed viral breakthrough and genotypic resistance after the LAM treatment and were treated with ADV monotherapy or ADV and LAM combination. However, the second line therapies were not effective in viral suppression and ADV resistance occurred in six patients. ETV or ADV and ETV combination treatment were used sequentially in some cases. TDF monotherapy or TDF and LAM combination was used for rescue therapy in these patients.9,10 The TDF based therapy was effective in suppressing HBV replication regardless of genotypic resistance pattern and previously used antiviral agents.

In this study, HBV DNA level decreased rapidly during 6 months of TDF treatment and remained at an undetectable level by real-time PCR assay (<20 IU/mL) at the last follow-up in the patients. TDF is a nucleotide analogue related to ADV and has an antiviral activity against wild type HBV and also LAM resistant HBV in vitro.15,16 Recent studies on efficacy of TDF or TDF combination therapy demonstrated that TDF treatment is highly effective in viral suppression in both naïve patients and patients with multidrug resistant HBV or suboptimal response to antiviral therapy.9-11 van Bommel et al.17 have reported that TDF rescue therapy strongly suppressed HBV DNA level in CHB patients who failed to achieve virological response to sequential ADV treatment for LAM resistance. The antiviral response was independent to the presence of LAM resistant mutation at baseline. TDF treatment also showed potent viral suppression in patients with suboptimal response to ETV treatment.10

In this study, five patients developed viral breakthrough during the TDF therapy, and all of them skipped TDF before the development of viral breakthrough. Pattern of the virological relapse was variable, although HBV DNA decreased after restart of the TDF treatment. Genotypic analysis was available in only two patients, and they showed no significant resistant mutations. Rapid increase of HBV DNA within one month of discontinuation was observed in a patient who also showed elevated level of bilirubin and transaminases. However, most patients with viral rebound did not show ALT flare. TDF has a potent antiviral activity, and the relapse after discontinuation could be abrupt and induce hepatic dysfunction. Drug adherence has been reported an important factor of viral breakthrough and virological response.18 Therefore, patient education and close monitoring of adherence to medication should be performed to improve the virological response and prevent the relapse.

An in vitro study showed that HBV clones harboring rtN236T or rtA181V decreased susceptibility to TDF about four times.19 This finding suggests TDF has a partial cross-resistance to ADV resistant HBV clones. We used TDF or TDF and LAM combination by clinicians' choice. All patients had excellent virological response irrespective of treatment regimen or the presence of ADV resistant mutation. In this study, five patients with virological relapse showed rapid decrease in HBV DNA after restoration of TDF treatment. However, some patients had detectable HBV DNA at last follow-up. It might be due to short duration TDF retreatment or possibly pre-exsisting rt181 or rt236 mutations. Difference in virological response could not be evaluated because of small number of the patients in our study. Berg et al.20 reported that TDF monotherapy and combination of TDF and emtricitabine had similar efficacy in patients with incomplete virological response after ADV therapy. The virological response was independent of pre-existing ADV or LAM resistant mutation. Tan et al.21 reported that TDF monotherapy or combination with emtricitabine had a potent antiviral activity in patients who showed ADV resistance or suboptimal response, and no novel mutation was detected during the TDF therapy. The persistent or emerging ADV resistant mutation reduces the antiviral response during the TDF monotherapy, and emtricitabine combined with TDF resulted in undetectable level of HBV DNA. Thus, they suggested that combination treatment might be more effective in ADV resistant cases.21 However, the role of combination of nucleoside with TDF is still under investigation. A randomized controlled trial is needed to evaluate the efficacy and resistance incidence of TDF based combination therapy in LAM or ADV resistant HBV patients.

TDF was well tolerated during the treatment period, and no patient showed TDF treatment induced renal impairment even in the patient with pretreatment elevation in creatinine level. Renal impairment has been observed in HIV infected patients with TDF therapy, particularly in patients with preexisting renal disease.22 However, long-term data up to 3 years of TDF treatment in CHB patients demonstrated less than 1% of the patients had a confirmed 0.5 mg/dL increase in creatinine.23 Long-term use of oral antiviral agents is indispensable for the complete suppression of HBV, therefore, identification and prevention of adverse events are important for the maintenance of the medication. Renal function should be monitored closely during long-term use of TDF.

This study has limitations because it is a small scale retrospective observational study with rather heterogeneous baseline characteristics (17 patients; 10 with LAM+ADV, two with ETV+ADV, two switch to ADV monotherapy, and three switch to ETV monotherapy). In genotypic analysis, 11 patients showed LAM resistance, six patients showed multidrug resistance and different treatment strategies (four with TDF monotherapy, 13 with TDF and LAM combination therapy). During virological relapse, sequencing of HBV DNA polymerase gene was performed in two patients, and there was no remarkable resistant mutation. However, we did not test rt194T mutation known as resistant mutation to TDF in the other patients. Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al.,24 the rtA194T polymerase mutation has been found in HBV/HIV coinfected patients during TDF treatment and may be associated with TDF resistance. The rtA194T polymerase mutation is associated with partial TDF drug resistance. But Delaney et al.,25 rtA194T did not cause a significant change in TDF susceptibility either alone or when expressed in combinated with LAM resistance mutations (1.5- to 2.5-fold). Whether the rtA194T mutation truly confers resistance against TDF has remained controversial. As for safety, renal function showed no significant changes, but we could not evaluate proximal tubular dysfunction which may occur during the long-term therapy with TDF or ADV. Despite these shortcomings, our results may be valuable to demonstrate the virological response and safety in the patients with multidrug resistant HBV treated with long-term use of TDF in Korea. Most studies on TDF treatment for patients with antiviral resistant HBV are clinical observations in a small number of CHB patients. A systemically designed trial in a large number of patients is needed to evaluate antiviral treatment strategy in CHB patients with multidrug resistance.

In conclusion, these results suggest that TDF based treatment has potent antiviral activity and safety during the long-term administration in CHB patients who had suboptimal response or multidrug resistance of previous antiviral therapy. Adherence is important to maintain the viral suppression during the therapy. Close monitoring of patients' adherence and HBV DNA level should be necessary to prevent virological relapse.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808–816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yotsuyanagi H, Koike K. Drug resistance in antiviral treatment for infections with hepatitis B and C viruses. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:329–335. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714–1722. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2008;48:750–758. doi: 10.1002/hep.22414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson SJ, George J, Strasser SI, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate rescue therapy following failure of both lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2011;60:247–254. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan CQ, Hu KQ, Yu AS, Chen W, Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Response to tenofovir monotherapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with prior suboptimal response to entecavir. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen J, Ratziu V, Buti M, et al. Entecavir plus tenofovir combination as rescue therapy in pre-treated chronic hepatitis B patients: an international multicenter cohort study. J Hepatol. 2012;56:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YS, Suh DJ, Lim YS, et al. Increased risk of adefovir resistance in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B after 48 weeks of adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/hep.21189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung SK, Chae HB, Fontana RJ, et al. Virologic response and resistance to adefovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2006;44:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, et al. Rescue therapy for lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B: comparison between entecavir 1.0 mg monotherapy, adefovir monotherapy and adefovir add-on lamivudine combination therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1374–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ying C, De Clercq E, Neyts J. Lamivudine, adefovir and tenofovir exhibit long-lasting anti-hepatitis B virus activity in cell culture. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:79–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying C, De Clercq E, Nicholson W, Furman P, Neyts J. Inhibition of the replication of the DNA polymerase M550V mutation variant of human hepatitis B virus by adefovir, tenofovir, L-FMAU, DAPD, penciclovir and lobucavir. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:161–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2000.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Bommel F, Zollner B, Sarrazin C, et al. Tenofovir for patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and high HBV DNA level during adefovir therapy. Hepatology. 2006;44:318–325. doi: 10.1002/hep.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hongthanakorn C, Chotiyaputta W, Oberhelman K, et al. Virological breakthrough and resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving nucleos(t)ide analogues in clinical practice. Hepatology. 2011;53:1854–1863. doi: 10.1002/hep.24318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi X, Xiong S, Yang H, Miller M, Delaney WE., 4th In vitro susceptibility of adefovir-associated hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations to other antiviral agents. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg T, Marcellin P, Zoulim F, et al. Tenofovir is effective alone or with emtricitabine in adefovir-treated patients with chronic-hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1207–1217. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan J, Degertekin B, Wong SN, Husain M, Oberhelman K, Lok AS. Tenofovir monotherapy is effective in hepatitis B patients with antiviral treatment failure to adefovir in the absence of adefovir-resistant mutations. J Hepatol. 2008;48:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch D, Connolly JO. Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:773–780. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132–143. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Herbers U, Sheldon J, Luedde T, Trautwein C, Tacke F. The rtA194T polymerase mutation impacts viral replication and susceptibility to tenofovir in hepatitis B e antigen-positive and hepatitis B e antigen-negative hepatitis B virus strains. Hepatology. 2009;49:1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney WE, 4th, Ray AS, Yang H, et al. Intracellular metabolism and in vitro activity of tenofovir against hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2471–2477. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00138-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]