Abstract

Core/shell heterostructure composite has great potential applications in photocatalytic field because the introduction of core can remarkably improve charge transport and enhance the electron-hole separation. Herein, hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell structured microspheres were prepared via a simple one-pot hydrothermal process based on different growth rate of the two kinds of sulphides. The results showed that, the as-prepared hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell heterostructure exhibits significant visible light photocatalytic activity for degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol. The introduction of Bi2S3 core can not only improve charge transport and enhance the electron-hole separation, but also broaden the visible light response. The hierarchical porous folwer-like shell of In2S3 could increase the specific surface area and remarkably enhanced the chemical stability of Bi2S3 against oxidation.

Recently, the design and synthesis of core/shell materials from nanoscale to microscale size have attracted much attention due to their unique structure-induced properties1,2,3. The interactions between the core and shell can significantly improve the overall performance of the core/shell system and even produce beneficial synergistic effects, which may bring a series of opportunities for their potential applications such as photoelectric devices, sensors and chemical catalysis4,5,6. In particular, hierarchical core/shell heterostructure photocatalysts have displayed superior photocatalytic efficiency because proper junctions formed between core and shell can efficiently accelerate charge separation and the large surface area can increase the active sites and light utilization7,8,9, so develop a simple method to prepare hierarchical core/shell heterostructures deserve researching.

Metal sulfides have been extensively investigated and proven to be a group of highly efficient catalysts for photochemical reactions. Typically, In2S3 nanostructure, a III-VI group sulfide, is known to crystallize in three polymorphic forms: α-In2S3, β-In2S3, and γ- In2S3. Of these, β- In2S3 is a n-type semiconductor with a band gap of 2.0–2.3 eV and is a potential candidate for photocatalytic applications because of its proper band gap for solar energy conversion10,11. Bi2S3 with a narrow bandgap (~1.3 eV) can be a good candidate semiconductor12,13. It has been used as a sensitizer due to its ability to absorb a large part of visible light up to 800 nm14,15. However, both of them exhibit relatively low photocatalytic activity. To improve the photocatalytic activity, it is highly desirable to fabricate In2S3/Bi2S3 core/shell heterostructure composite, which can efficiently promote charge separation and lead to enhanced activity. So the combination of In2S3 and Bi2S3 in a single core/shell composite could hold possible applications in energy conversion for the photodegradation reaction, which has not been reported yet.

In all cases to date, general synthesis strategies used to fabricate core/shell structures involve two main steps. The core powders are first prepared, and then coated with other materials (shell) to form a core–shell structure. It is difficult to achieve uniform coating with well-defined morphologies due to compatibility issues between the core and desired shell materials. Therefore, how to construct hierarchical heterogeneous core/shell structures via a facile one-spot route is still a significant challenge to material scientists.

Herein, we reported a facile route for growth rate controlled synthesis of hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell microspheres via a hydrothermal process. In this process, consecutive reactions of the sole sulfur source of L-cysteine with Bi and In salts lead to the formation of Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell structures due to their significantly different reaction rate. The as-prepared core/shell hybrid has an interesting structure with uniform size consisting of a Bi2S3 sphere core and a nanosheet-based In2S3 shell. The special hierarchical structure, high light-harvesting capacity and the microscale core/shell heterostructure make it to be an excellent candidate for the degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol with enhanced photostability and photocatalytic efficiency.

Results

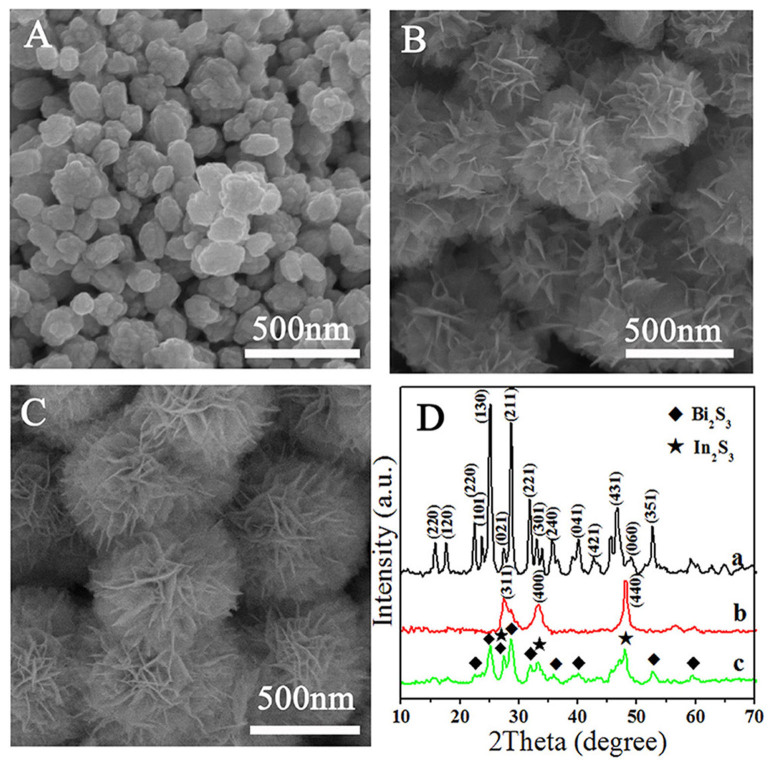

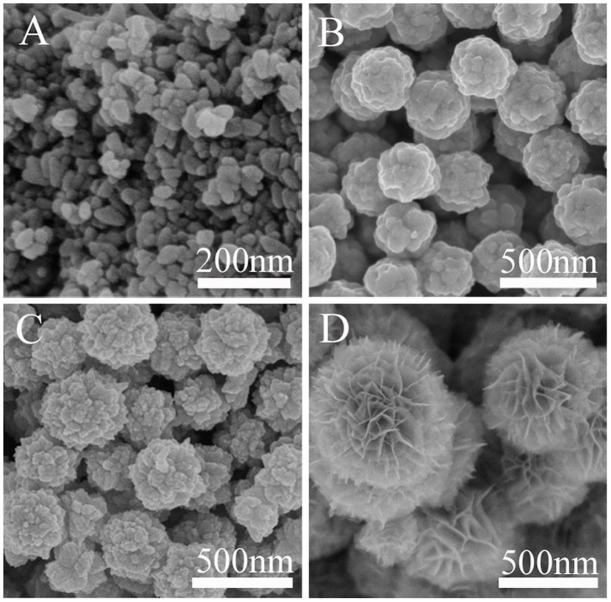

The morphology and the crystal phase information of the final products were investigated by SEM and XRD analysis, as shown in Figure 1. From the comparison of the SEM images we could clearly see that bare Bi2S3 is composed of nanospheres with an average diameter of 100–200 nm (Figure 1A). As for pure In2S3, flower-like structure with an average size of 400 nm could be easily obtained, and its surface is made up by thin nanosheets (Figure 1B). Interestingly, Figure 1C clearly indicates that Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite is a uniform flower-like spherical superstructure composed of numerous intercrossed ultrathin nanosheets. The average diameter of these superstructures is about 500 nm, which is a little bit larger than the size of pure In2S3. This change infers that In2S3 nanosheets may grow along the core of Bi2S3 nanoparticles in the Bi2S3/In2S3 composites. The phase and purity of these samples were determined by XRD measurements (Figure 1D). The X-ray diffraction spectra of a and b shown in Figure 1D reveal the presence of Bi2S3 and In2S3, respectively. Correspondingly, all the peaks can be indexed to a pure orthorhombic phase Bi2S3 (JCPDS card No. 17-0320) and cubic β-In2S3 (JCPDS Card No. 32-0456). For hierarchical core/shell spherical superstructure (Line c in Figure 1D), diffraction peaks of In2S3 match with the reflections from the cubic β-In2S3 lattice planes of (311), (400) and (440), making it easy to reveal the presence of In2S3 phase. In contrast, other diffraction peaks can be attributed to orthorhombic phase Bi2S3. All the above results suggest that the intercrossed In2S3 nanosheet shell could in situ grow on the surface of Bi2S3 core.

Figure 1. SEM images of Bi2S3 (A), In2S3 (B), hierarchical In2S3/Bi2S3 core/shell hybrid (In-Bi-30) (C), and XRD pattern (D) of the three samples: Bi2S3 (a), In2S3 (b), hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell hybrid (In-Bi-30) (c).

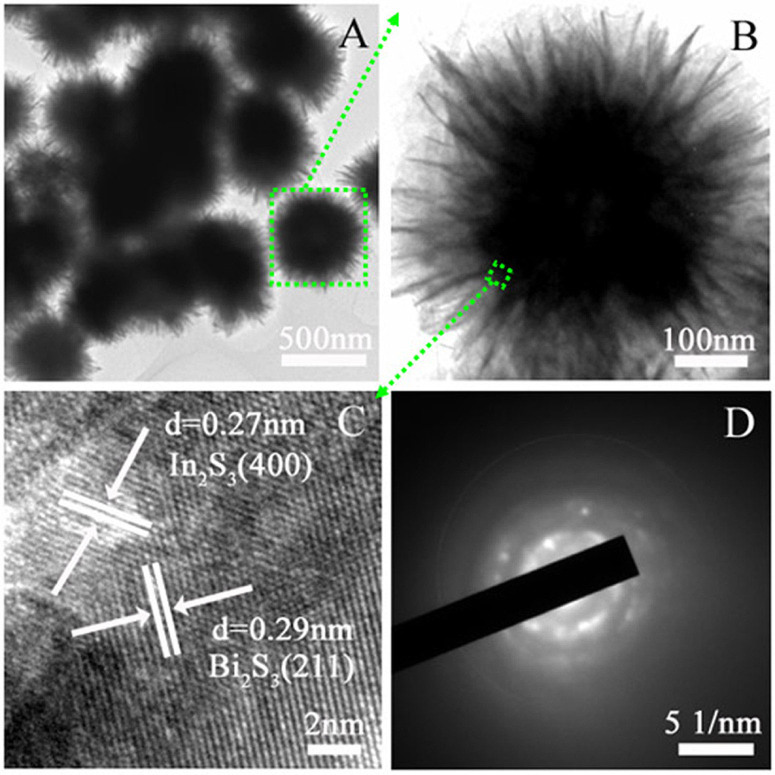

Additionally, the more detailed structural information of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 composite was revealed using TEM and HRTEM. As shown in Figure 2A, ultrathin nanosheets grow uniformly on the surface of solid sphere core and the thickness of the nanosheets is estimated to be 3–5 nm measured from the edges (Figure 2B). The HRTEM image of the core-shell structure (Figure 2C) reveals that the interplanar spacing of 0.29 nm corresponds to the (211) plane of Bi2S3, while 0.27 nm corresponds to the (400) plane of cubic β-In2S3, which implying the formation of Bi2S3/In2S3 heterostructure. The selected area electron diffraction pattern (SAED) image in Figure 2D further proves its polycrystalline mixed-phase nature. It should be noted that our as-synthesized Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres have a small diameter and the constituent nanosheets are very thin, which would contribute to the light-harvesting in the photocatalytic reaction.

Figure 2. TEM (A, B), HRTEM (C) and the selected area electron diffraction pattern (D) images of the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres (In-Bi-30).

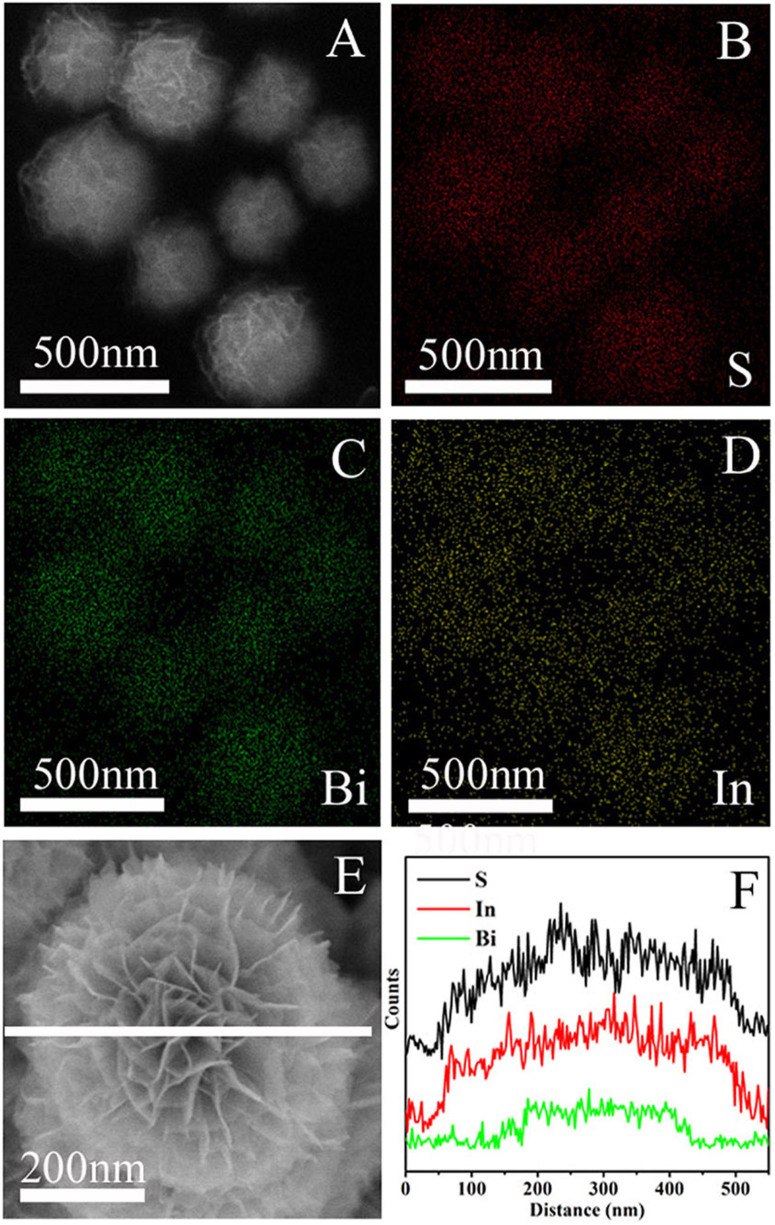

To further accurately investigate the elemental composition as well as the spatial uniformity of the elemental distribution, X-ray energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) was carried out on Bi2S3/In2S3 spheres (Figure 3). The EDS mapping images indicate the coexistence of S, Bi and In elements in the submicrosphere (Figure 3B–D). The S element mapping (Figure 3B) confirms the homogeneous distribution among the whole architecture, but for the other two elements, the diameter of Bi element mapping distribution is smaller (Figure 3C) than that of In element mapping distribution (Figure 3D), which confirms that the In2S3 nanosheets are densely and uniformly decorated on the surface of the Bi2S3 cores. Besides, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) line scans on single submicrosphere (Figure 3F) show that the synthesized flower-like Bi2S3/In2S3 spheres are indeed unique structures with the Bi2S3 cores buried inside the In2S3 shells.

Figure 3. SEM image (A) of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres (In-Bi-30) and the corresponding EDS mapping of S (B, red), Bi (C, green) and In (D, yellow); single Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell sphere SEM image (E) and corresponding EDS line scan profiles (F) of S (K edge), In (L edge) and Bi (L edge) across the sphere displayed in the (E).

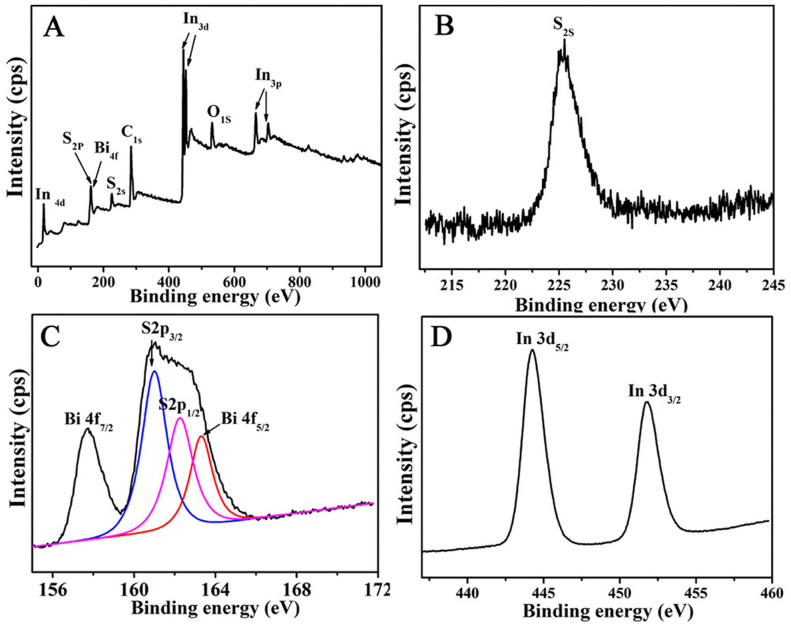

The surface valence state and the chemical composition of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite were further characterized by XPS. Figure 4A clearly indicates that the product is mainly composed of S, Bi and In elements (C and O signals come from the reference sample and absorbed oxygen). High-resolution scans of the three elements reveal several prominent peaks centered at around 225.2 (Figure 4B), 160.5, 157.75 (Figure 4C), and 444.8 eV (Figure 4D), which can be accordingly assigned to binding energies of S2s, S2p3/2, Bi4f7/2, and In3d5/216,17. Moreover, phenomena of spin orbit separation between Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2 peaks (5.30 eV), S2p3/2 and S2p1/2 peaks (1.25 eV) (Figure 4C), and In 3d5/2 and In 3d3/2 peaks (7.5 eV) (Figure 4D) suggest the existence of S2+, Bi3+ and In3+ in the final product, which is in agreement with previous reports18,19.

Figure 4. The survey XPS spectrum (A) of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite (In-Bi-30) and the high-resolution scan of S2s (B), Bi4f and S2p (C) and In 3d peaks (D) of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite (In-Bi-30).

For highly efficient photocatalyst, light absorption range and intensity are important. The optical absorption properties of Bi2S3, In2S3 and the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite are displayed in the Figure S1. According to the UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra, both Bi2S3 and In2S3 present the photoresponse property from UV light region to visible light region. Compared with bare Bi2S3, the light absorption ability of the core/shell material is enhanced after In2S3 was introduced, which has strong absorption in nearly the whole range of visible light. This can be attributed to the small band gap and synergistic affect of the two compositions. Taking into account the efficient use of visible light in a large part of the solar spectrum, we believe that this photocatalyst, with its long wavelength absorption band, is an attractive photocatalyst for pollutant degradation.

To investigate the formation process of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres, samples prepared at different reaction times were collected and investigated by SEM. As shown in Figure 5A, at the early reaction stage (20 min), the product was composed of nanoparticles (15–25 nm). The corresponding EDS spectrum (Figure S2A a) inferred that these nanoparticles were composed of Bi and S elements, indicating the fast nucleation of Bi2S3 under hydrothermal condition. By prolonging the reaction time to 1 h, small nanoparticles congregated into compact submicrospheres (200–300 nm, Figure 5B) rapidly, and there were numerous small protuberances on the surface of the submicrospheres, which would provide many high energy sites for further growth20. The EDS analysis (Figure S2A b) inferred the submicrosphere was also the phase of Bi2S3. As the reaction proceeded (Figure 5C), In3+ and S2− could get enough energy to crystallize into In2S3 nanoparticles on the surface of Bi2S3 core. Meanwhile, the presence of In element (Figure S2A c) also proved the appearance of In2S3 in the composite. As the mass diffusion and Ostwald ripening process progressed, In2S3 nanosheets shell formed (Figure 5D), accompanied by their self-organization onto the Bi2S3 core to form hierarchical structure through a nucleation-aggregation-deposition pathway after the reaction was carried out for 9 h (Figure S2A d), and the average size of these spheres was about 500 nm. Furthermore, for the samples prepared from different reaction time, the content of In element increased along with prolonging the reaction time according to the EDS results (Figure S2A and Table S1).

Figure 5. SEM images of the products obtained at 20 min (A), 1 h (B), 3 h (C) and 9 h (D) in one-pot reaction.

Corresponding X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Figure S2B) show the presence of crystalline Bi2S3 as the reaction time ranging from 20 min to 9 h. The diffraction peaks of In2S3 can hardly be found when reaction time was short (Figure S2B a and b), but the diffraction peaks of In2S3 started to emerge as the experiment was conducted for 3 h (Figure S2B c), and the diffraction peak intensity increased with the extension of reaction time (Figure S2B d). Furthermore, the peak intensity of Bi2S3 decreased to some extent as time prolonged, which further inferred that Bi2S3 was wrapped by the In2S3 shell and matched with the SEM (Figure 5) and EDS (Figure S2A) observations.

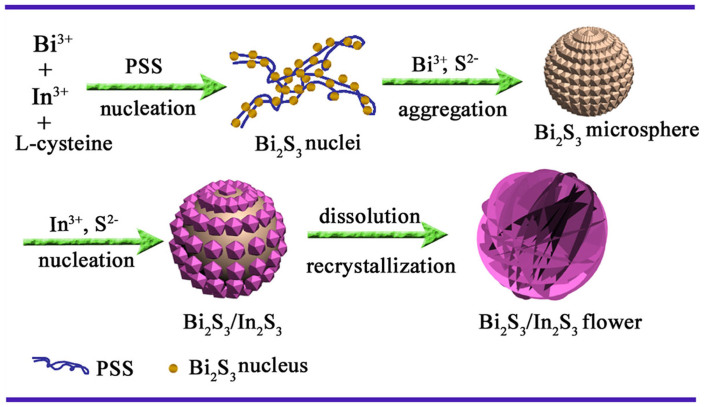

Based on the above experimental results and analysis, the probable morphology evolution process of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres is illustrated in Figure 6. Compared with the general S sources (such as S powder, thiourea, Na2S and thioacetamide) used in the synthesis of semiconductor metal sulfides21, L-cysteine is an ordinary acidic amino acid biomolecule, which may avoid the cations hydrolyzing intensively, and the thiol groups can slowly supply S2− in solution during the hydrothermal process. In the L-cysteine molecule, there are many functional groups, such as -NH2, -COOH, and -SH, which have a strong tendency to coordinate with inorganic cations and metals22. Besides, it has been reported that poly (sodium-p-styrenesul-fonate) (PSS) is an anionic surfactant with a long chain structure, which can provide many coordination sites for cations and other groups23, this has also been proved by our previous report24. In our experiment, the presence of an appropriate amount of surfactant PSS was crucial for the formation of this unique hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres structure with small size. Our contrast experiment (Figure S3) result showed that without PSS, the size of the product was not uniformly and much larger than Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spheres (In-Bi-30). Notably, there were different morphologies in the final product, which indicated that In2S3 and Bi2S3 can't grow intimately to form core/shell structure. Therefore, under the help of mutual coordination between PSS and L-cysteine, Bi3+ and In3+ can coordinate with L-cysteine to form initial precursor complexes on the long chain structure of PSS25,26. At elevated reaction temperature, L-cysteine hydrolyzed to release H2S with the assistance of water. Because the Ksp of Bi2S3 (1.0 × 10−97) is much smaller than that of In2S3 (5.7 × 10−73)27, it is expected that Bi2S3 will preferentially deposit and form crystal seeds along the PSS chain before In2S3 (Figure 5A). Since PSS long chains were flexible enough to interweave, the Bi2S3 nuclei tended to aggregate into larger spheres along with the continuous crystallization of Bi2S3 (Figure 5B). As the reaction proceeded, nucleation process of In2S3 was initialized when Bi3+ was depleted (Figure 5C). The as-produced In2S3 nanoparticles preferentially deposited on the surfaces of the preformed Bi2S3 spheres via epitaxial growth process to reduce their surface energy18. Further extending the reaction time, the outward In2S3 nanoparticles could get enough energy to dissolve into the solution and spontaneously nucleated onto these protuberances. As the mass diffusion and Ostwald ripening process progressed, the nanosheets formed accompanied with their self-organization into the flower-like structure28. Finally, the submicrospheres were constructed into hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spherical structures (Figure 5 D).

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of the morphological evolution process of the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell spherical structure.

Discussion

Compared to the conventional synthetic methods, this one-spot synthetic route is simple and easy to achieve uniform coating with hierarchical nanosheets due to compatibility issues between the Bi2S3 core and In2S3 shell. Moreover, the In2S3 shell thickness and morphology can be easily controlled by altering the ratio of In2S3 in the Bi2S3/In2S3 architecture and reaction time. In order to obtain a higher efficient photocatalytic catalyst, we adjusted the ratio of In2S3 in the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell architectures, the morphologies were shown in Figure S4. When the content of In2S3 was low, the nanosheets on the surface of the microspheres were not obviously and the size was smaller (Figure S4A) than the In-Bi-30 sample (Figure S4B), indicating the formation of nanosheets needed sufficient amount of In2S3. Obviously, without fluffy nanosheets on the surface, the multiple light reflection would be reduced in the composite, which will reduce light-harvesting and thus decrease the quantity of photogenerated electrons and holes29. However, excess In2S3 (In-Bi-50) could make the nanosheets much thicker and radius much larger (Figure S4C), which would lead to the decrease of BET surface area, just as shown in Figure S5, Table S2. The corresponding BET surface areas and porous structures of different samples were investigated using nitrogen adsorption–desorption experiments (Figure S5). The pore-size distributions (the inset in Figure S5) of the samples indicate a pore-size distribution from 2 to 4 nm, confirming the presence of a large number of mesopores. Compared with Bi2S3 nanospheres, the BET surface areas of core/shell Bi2S3/In2S3 samples were improved (Table S2), especially the value of In-Bi-30, which was close to the BET surface area of In2S3 (76 m2/g). This can be attributed to its smaller particle size, ultrathin nanosheets and the presence of large quantity of mesoporous. The large surface area for heterogeneous photocatalysis can provide more surface active sites for the adsorption of reactant molecules, which will make the photocatalytic process more efficient30. But too thick a shell of the composite (In-Bi-50) caused the size of microspheres to become larger and the BET surface area smaller, meanwhile extended the diffusion length of charge-carrier transport in the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell hybrid to increase bulk combination in In2S3 or Bi2S3, which are not beneficial for the photocatalytic reaction. So we predicted that the hierarchical flower-like core/shell Bi2S3/In2S3 (In-Bi-30) with heterostructure and ultrathin nanosheets will have higher photocatalytic ability than other samples.

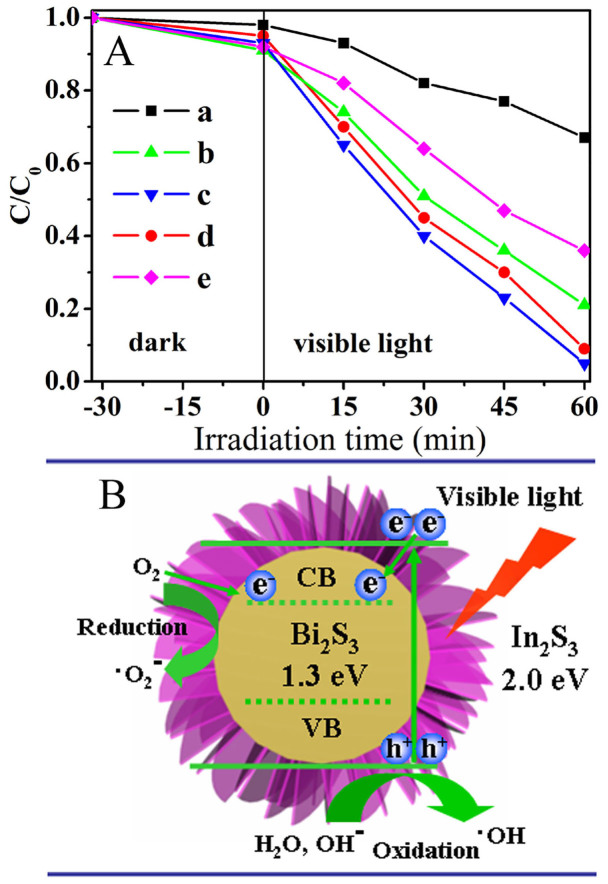

Considering the core/shell architectures with special hierarchical nanocomposites are advantageous to photocatalytic application, we investigate the photocatalytic properties of as-prepared hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell nanostructures by the degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol under visible light irradiation in an aqueous solution, together with that of Bi2S3 and In2S3 for the purpose of comparison. Before the photocatalytic reaction, the dark adsorption experiments were performed. As shown in Figure 7A, the dark adsorption amounts of pure In2S3 and In-Bi-30 were high, which associate with their high BET surface areas. After irradiation, the plots for the concentration changes of 2, 4-dichlorophenol determined from its characteristic absorption peak over different catalysts are altered. It can be seen that all the In2S3/Bi2S3 core/shell composites show higher photocatalytic activities than individual Bi2S3 and In2S3 under identical experimental conditions. As discussed above, the hierarchical core/shell structure of the In2S3/Bi2S3 composites improves the light absorption and facilitates the efficient separation of photogenerated carriers, which can be considered as main reasons for the enhancement of photocatalytic activities. The photocatalytic mechanism was shown in Figure 7B. Under visible-light illumination, photogenerated electrons are excited from the value band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) of In2S3. Because the CB of In2S3 is slightly higher than that of Bi2S3, the photoexcited electrons in the CB of In2S3 can be transferred to Bi2S3 in the core/shell hybrid nanostructure easily, creating positive holes in the VB of In2S3. Importantly, the In2S3 shell is made up of ultrathin nanosheets with intersection, there exist lots of porous channels, the oxygen could permeate through the shell to the core of Bi2S3. Since the ECB potential of Bi2S3 (−0.76 eV vs NHE) is more negative than E0 (O2/·O2-) (−0.046 eV vs NHE), the electrons left on the ECB of Bi2S3 could reduce O2 to ·O2- through one-electron reducing reaction31. Meanwhile, due to the high oxidizing potential, the formed holes may react with H2O or OH− in the solution, generating hydroxyl (·OH) radicals adsorbed at the surface32,33. All the radicals can react with organic chemicals in the solution and improve the photoactivity. It should be pointed out that the amount of In2S3 has obvious influence on the photocatalytic ability in the present material system (Figure 7A b–d). When the amount of In2S3 is relatively low (In-Bi-10), the small surface area of Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell nanostructure provides relatively low surface active sites for the adsorption of reactant molecules. Increase the amount of In2S3, hierarchical core–shell structure was formed (In-Bi-30), the degradation rates of 2, 4-dichlorophenol reached the maximum value (95%, Figure 7A c). Further adding the In2S3 content also reduced the catalytic efficiency of the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell nanostructures, suggesting that a too thick In2S3 shell was unfavorable to the degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol owing to the increased recombination of excited holes and electrons. These systematic changes further demonstrate the favorable role of the core/shell-structured Bi2S3/In2S3 catalyst in the preferential degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol by the photogenerated holes and electrons. In addition, the inter-meshed nanosheets of hierarchical superstructure (In-Bi-30) can allow multiple reflections of visible light, which enhances light-harvesting and thus increases the quantity of photogenerated electrons and holes available to participate in the photocatalytic degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol34.

Figure 7.

(A) Photocatalytic degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol by different photocatalysts under visible light irradiation: Bi2S3 (a), In-Bi-10 (b), In-Bi-30 (c), In-Bi-50 (d) In2S3 (e). C and C0 are the initial concentration after the equilibrium adsorption and the reaction concentration of 2, 4-dichlorophenol, respectively. (B) Schematic illustration showing the reaction mechanism for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants over the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite.

To further prove the mechanism of the photocatalysis, the formation of OH on the surface of photocatalysts was detected by the fluorescence technique using terephthalic acid (TA) as a probe molecule. It is well known that •OH reacts with terephthalic acid (TA) in basic solution to generate 2-hydroxy-terephthalic acid (TAOH), which emits a unique fluorescence signal with the peak centered at 426 nm35. The fluorescence intensity of TAOH is proportional to the amount of·OH produced on the surface of photocatalysts. The maximum emission intensity in fluorescence spectra was recorded at 425 nm by the excitation at 315 nm, and the results are shown in Figure S6. It clearly demonstrates that the photoexcited holes are powerful enough to oxidize surface-adsorbed hydroxy groups and water molecules to generate •OH radicals. Obviously, the maximum number of •OH radicals is formed by using the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell photocatalyst (In-Bi-30) in the photoreaction process, this result is in good agreement with the result of photodegradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol. Hence, the photocatalytic activity has a positive correlation with the formation rate of •OH radicals36. Besides, the trapping experiments of active species during the photocatalytic reaction were performed. Isopropanol (IPA) and benzoquinone (BQ) acted as the scavengers for ·OH and ·O2-, respectively37. Figure S7 displays the results of different scavengers on the photodegradation rate over the sample of Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell nanostructure (In-Bi-30) with 30 min irradiation. It can be seen that the addition of IPA and BQ in the reaction solution both have apparent effect on the photocatalytic activity, suggesting that •OH and ·O2- are the main oxygen active species involved in the 2, 4-dichlorophenol photocatalytic process under visible light irradiation. All of the above results could well support the proposed photocatalytic mechanism in Figure 7B.

Metal sulfides are usually not stable during the photocatalytic reaction and subjected to photocorrosion38,39. In our experiment, the stability of the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell structure (In-Bi-30) and pure Bi2S3 and In2S3 were evaluated by performing the cycling experiments under the same conditions (Figure S8). After four recycles, the photocatalytic degradation rate of sample Bi2S3 and In2S3 decreases gradually, however the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell structure (In-Bi-30) does not exhibit evident loss of activity, indicating the better stability of this Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell composite. The high stability of the Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell structure is attributed to the close interaction between Bi2S3 and In2S3 solid solution, which favors the transfer of the photogenerated electrons from the conduction band (CB) of In2S3 to Bi2S3 conduction band (CB), as shown in Figure 7B. This space separation of the photogenerated electrons and holes is beneficial for preventing the reduction of In3+ and Bi3+.

In summary, we demonstrated a facile one-pot hydrothermal method to synthesize hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell microspheres according to the different growth rate of the two kinds of sulphides. Moreover, their performance studies indicated the hierarchical Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell microspheres exhibit higher photocatalytic activity than the pure Bi2S3 and In2S3 for the degradation of 2, 4-dichlorophenol due to the efficient synergistic effect resulted from the interaction between Bi2S3 core and hierarchical In2S3 shell. The synergistic activity was also investigated through the measurement of •OH and ·O2- radicals produced by Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell microspheres. It is considered that this facile and promising synthetic strategy can be extended to prepare a wide variety of functional nanohybrids for potential applications in waste water treatment, solar cells and so on.

Methods

Preparation of Bi2S3/In2S3 core/shell microspheres

In a typical experiment, 0.3 g Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, 0.15 g poly (sodium-p-styrenesul-fonate) (PSS), a specified quality of In(NO3)3·4.5H2O and L-cysteine were added into 25 mL distilled water and stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the obtained yellow solution was transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, which was heated to 150°C and maintained for 9 h. After cooling, the as-synthesized brown products were rinsed with distilled water, absolute ethanol, respectively, and dried at 60°C overnight. The molar ratios of In3+ to Bi3+ were 10%, 30%, and 50%, and the resulting samples were labeled as In-Bi-10, In-Bi-30 and In-Bi-50, respectively. For comparison, bare In2S3 and Bi2S3 were obtained under the same experimental conditions in the absence of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and In(NO3)3·4.5H2O, respectively.

Materials characterization

Structure and morphology of the product was investigated by Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan), SEM-EDS analyses were carried out with a Hitachi S-4800 SEM equipped with an EDAX energy dispersive X-ray analyzer. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL 2100, Japan), and powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance using CuKa radiation). The UV-visible diffuse reflectance spectra of films were obtained using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2550). The electronic states of elements in the sample were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Kratos-AXIS UL TRA DLD, Al Ka X- ray source). The specific surface areas of the materials were calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method.

Photocatalytic properties study

The photodegradation experiments were performed in a slurry reactor containing 100 mL of 50 mg/L 2, 4-dichlorophenol and 0.05 g of catalyst. An 150 W xenon lamp (Institute of Electric Light Source, Beijing) was used as the solar-simulated light source, and visible light was achieved by utilizing a UV cut filter (λ ≥ 420 nm). Prior to light irradiation, the suspension was kept in the dark under stirring for 30 min to ensure the establishing of an adsorption/desorption equilibrium. Oxygen flow was employed in all experiments as oxidant. Adequate aliquots (5 mL) of the sample were withdrawn after periodic interval of irradiation, and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 5 min, then filtered through a Milipore filter (pore size 0.22 μm) to remove the residual catalyst particulates for analysis. The filtrates were analyzed using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2550).

In order to detect the active species during the photocatalytic reaction, hydroxyl (•OH) radicals produced by the photocatalysts under visible light irradiation were measured by the fluorescence method on a Fluoromax-4 Spectrophotometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon) using terephthalic acid (TA) as a probe molecule. The •OH radical trapping experiments were carried out using the following procedure: A 5 mg portion of the sample was dispersed in 30 mL of a 5 × 10−4 M TA aqueous solution in a diluted NaOH aqueous solution (2 × 10−3 M). The resulting suspension was then exposed to visible light irradiation for 15 min. 2 mL of the suspension was collected and centrifuged to measure the maximum fluorescence emission intensity with an excitation wavelength of 315 nm. Besides, isopropanol (IPA, 10 mM), and benzoquinone (BQ, 6 mM) were added into the 2, 4-dichlorophenol solution to capture hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and the superoxide radicals (·O2-), respectively, followed by the photocatalytic activity test.

Author Contributions

J.Z. performed synthesis experiments, G.H.T. and H.G.F. designed the experiment. Y.J.C. and Y.H.S. contributed in material characterization and discussion. C.G.T. and K.P. carried out photocatalytic evaluation and discussion. J.Z. and G.H.T. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

dataset 1

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of this research by the Key Program Projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 21031001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51272070, 91122018, 20971040), the Cultivation Fund of the Key Scientific and Technical Innovation Project, Ministry of Education of China (No 708029), Program for Innovative Research Team in University (IRT-1237).

Footnotes

03/12/2014

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

- Xi G. C., Yue B. J., Cao Y. J. & Ye H. Fe3O4/WO3 Hierarchical Core–Shell Structure: High-Performance and Recyclable Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 5145–5154 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. D. et al. Formation of Hollow Nanocrystals Through the Nanoscale Kirkendall Effect. Science 304, 711–714 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ji S., Gao Y., Luo H. & Kanehira M. Core-shell VO2 @TiO2 nanorods that combine thermochromic and photocatalytic properties for application as energy-saving smart coatings. Sci. Rep., 10.1038/srep01370 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. J. et al. Supported Core@Shell Electrocatalysts for Fuel Cells: Close Encounter with Reality. Sci. Rep., 10.1038/srep01309 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H. C. Synthetic Architecture of Interior Space for Inorganic Nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. 16, 649–662 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Luo S. R. et al. Facile and fast synthesis of urchin-shaped Fe3O4@Bi2S3 core-shell hierarchical structures and their magnetically recyclable photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 4832–4836 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Self-Assembled 3D Flowerlike Hierarchical Fe3O4@Bi2O3 Core–Shell Architectures and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity under Visible Light. Chem Eur. J. 17, 4802–4808 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. H. & Tu J. P. High-Quality Metal Oxide Core/Shell Nanowire Arrays on Conductive Substrates for Electrochemical Energy Storage. ACS Nano 6, 5531–5538 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chueh Y. L. et al. RuO2 Nanowires and RuO2/TiO2 Core/Shell Nanowires: From Synthesis to Mechanical, Optical, Electrical, and Photoconductive Properties. Adv. Mater. 19, 143–149 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Asikainen T., Ritala M. & Leskela M. Growth of In2S3 thin films by atomic layer epitaxy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 82/83, 122–125 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Rengaraj S. et al. Self-Assembled Mesoporous Hierarchical-like In2S3 Hollow Microspheres Composed of Nanofibers and Nanosheets and Their Photocatalytic Activity. Langmuir 27, 5534–5541 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Zhou X. G., Zhang H. & Zhong X. H. Bi2S3 Nanostructures: A New Photocatalyst. Nano. Res. 3, 379–386 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bessekhouad Y., Mohammedi M. & Trari M. Hydrogen photoproduction from hydrogen sulfide on Bi2S3 catalyst. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 73, 339–350 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Robert D. et al. Photosensitization of TiO2 by MxOy and MxSy nanoparticles for heterogeneous photocatalysis applications. Catal. Today 122, 20–26 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bessekhouad Y., Robert D. & Weber J. V. Bi2S3/TiO2 and CdS/TiO2 heterojunctionsas an available configuration for photocatalytic degradation of organicpollutant. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 163, 569–580 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. et al. Morphology Control of β-In2S3 from Chrysanthemum-Like Microspheres to Hollow Microspheres: Synthesis and Electrochemical Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 113–117 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Grigas J., Talik E. & Lazauskas V. X-ray photoelectron spectra and electron structure of Bi2S3 crystals. Phys. Status Solidi. 232, 220–230 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z. et al. Epitaxial Growth of CdS Nanoparticle on Bi2S3 Nanowire and Photocatalytic Application of the Heterostructure. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 13968–13976 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. H. et al. Organothermal Synthesis and Characterization of Nanocrystalline β-Indium Sulfide. J. Am. J. Optoelectron. 82, 457–460 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Lezau A. et al. Mesostructured Fe Oxide Synthesized by Ligand-Assisted Templating with a Chelating Triol Surfactant. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 5211–5216 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. L. et al. Nanometer-Sized Copper Sulfide Hollow Spheres with Strong Optical-Limiting Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 1397–1401 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Hernández P. et al. Self-Assembled Monolayer of L-Cysteine on a Gold Electrode as a Support for Fatty Acid. Application to the Electroanalytical Determination of Unsaturated Fatty Acid. Electroanalysis 15, 1625–1631 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. Y., Rusling J. F. & Hu N. F. Electroactive Core–Shell Nanocluster Films of Heme Proteins, Polyelectrolytes, and Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 20, 10700–10705 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. et al. Synthesis of hierarchical TiO2 nanoflower with anatase–rutile heterojunction as Ag support for effcient visible-light photocatalytic activity. Dalton Trans. 42, 11242–11251 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. et al. Biomolecule-Assisted Synthesis and Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage of Bi2S3 Flowerlike Patterns with Well-Aligned Nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 8978–8985 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Y. Zhang Z. D. & Wang W. Z. Self-Assembled Porous 3D Flowerlike β-In2S3 Structures: Synthesis, Characterization, and Optical Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 4117–4123 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Knoxville T. N. & John A. D. Lange's Handbook of Chemistry (McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Luo S. R. et al. Facile and fast synthesis of urchin-shaped Fe3O4@Bi2S3 core-shell hierarchical structures and their magnetically recyclable photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 4832–4836 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Li H. X. et al. Mesoporous Titania Spheres with Tunable Chamber Stucture and Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 8406–8407 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. G. et al. Hydrothermal Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Hierarchically Sponge-like Macro/Mesoporous Titania. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 10582–10589 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. J. et al. In Situ Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Porous N-TiO2/g-C3N4 Heterojunctions with Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 17140–17150 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- He Y. H. et al. A New Application of Nanocrystal In2S3 in Efficient Degradation of Organic Pollutants under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 5254–5262 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z. et al. Nitrogen-doped mesoporous nanohybrids of TiO2 nanoparticles and HTiNbO5 nanosheets with a high visible-light photocatalytic activity and a good biocompatibility. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 19122–19131 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. & Yu J. C. A sonochemical approach to hierarchical porous titania spheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 2078–2079 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanchandani S. et al. Band Gap Tuning of ZnO/In2S3 Core/Shell Nanorod Arrays for Enhanced Visible Light-Driven Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 5558–5567 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. J. et al. An Exceptional Artifi cial Photocatalyst, Nih-CdSe/CdS Core/Shell Hybrid, Made In Situ from CdSe Quantum Dots and Nickel Salts for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 25, 6613–6618 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. h. et al. High-Effciency Visible-Light-Driven Ag3PO4/AgI Photocatalysts: Z- Scheme Photocatalytic Mechanism for Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 19346–19352 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. & Honda J. K. Visible-Light-Induced Water Cleavage and Stabilization of n-Type CdS to Photocorrosion with Surface-Attached Polypyrrole-Catalyst Coating. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 1933–1935 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Bao N. Z. et al. Facile Cd–Thiourea Complex Thermolysis Synthesis of Phase-Controlled CdS Nanocrystals for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production under Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 17527–17534 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

dataset 1