Summary

Pneumonia is common among critically ill burn patients and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among them. Prediction of mortality in patients with severe burns remains unreliable. The aim of this research is to study the incidence, early diagnosis and management of nosocomial pneumonia, and to discuss the relationship between pneumonia and death in burn patients. This prospective study was carried out on 80 burn patients (35 males and 45 females) admitted to Menoufiya University Hospital Burn Center and Chest Department, Egypt, from September 2011 to March 2012. Our findings showed an overall burn patient mortality rate of 26.25 % (21/80), 15% (12/80) incidence of pneumonia, and a 50% (6/12) mortality rate among patients with pneumonia compared to 22 % (15/68) for those without pneumonia. The incidence of pneumonia was twice as high in the subset of patients with inhalation injury as among those without inhalation injury (P< 0.001). It was found that the presence of pneumonia, inhalation injury, increased burn size, and advanced age were all associated with increased mortality (P< 0.001). In the late onset pneumonia, other associated factors also contributed to mortality. Severity of disease, severity of illness (APACHE score), organ failure, underlying co-morbidities, and VAP PIRO score all have significant correlations with mortality rate. Pneumonia was an important factor for predicting burn patient mortality. Early detection and management of pneumonia are absolutely essential.

Keywords: pneumonia, inhalation injury, mortality, burn

Abstract

La pneumonie est fréquente chez les grands brûlés et elle est une cause majeure de morbidité et de mortalité parmi eux. Prédiction de la mortalité chez les patients souffrant de brûlures graves reste peu fiable. Le but de cette recherche est d’étudier l’incidence, le diagnostic et le traitement de la pneumonie nosocomiale précoce et de discuter de la relation entre la pneumonie et la mort chez les patients brûlés. Cette étude a été réalisée sur 80 patients souffrant de brûlures (35 hommes et 45 femmes) admis au Centre des Brûlés à Menoufiya University Hospital en Egypte entre Septembre 2011 et Mars 2012. Nos résultats ont montré un taux de mortalité de 26,25% (21/80), l’incidence de la pneumonie de 15% (12/80), et un taux de mortalité chez les patients atteints de pneumonie de 50% (6/12) contre 22% (15/68) pour les patients sans pneumonie. La pneumonie était deux fois plus élevée dans le groupe de patients ayant une lésion par inhalation que chez ceux sans lésion par inhalation (P <0,001). Il a été constaté que la présence d’une pneumonie, d’une blessure à l’inhalation, d’une brûlure extensive, et d’un patient de l’âge avancé conduit à une mortalité accrue (P <0,001). Il y avait des associations de mortalité attribuables à la pneumonie d’apparition tardive. La gravité de la maladie (APACHE), la présence de défaillance d’un organe ou des comorbidités et le score PIRO VAP ont une corrélation significative avec le taux de mortalité. La pneumonie a été un facteur important pour prédire la mortalité des patients brûlés. Détection précoce et la gestion de la pneumonie sont absolument essentielles.

Introduction

Advances in burn care have produced an increase in survival rate of severely burned patients.1 Prediction of mortality in these patients remains unreliable.1 A simple and accurate system for objectively estimating the probability of death would be useful in counseling patients and making medical decisions.2 The most commonly used predictors of mortality in burns patients are age, burn size, and inhalation injury, while the following are significant predictors of increased mortality: large burn size, inhalation injury, delayed intravenous access, lower admission hematocrit, higher base deficit (BD) on admission, higher serum osmolality on arrival in hospital, sepsis, need of inotropic support, platelet count <20.000, and ventilator dependency during hospital stay.3 Pneumonia is also a major cause of morbidity and mortality in burn patients.5 The expected increase in mortality owing to pneumonia has been estimated to be 25% in a retrospective cohort study.6 Clinical study of pneumonia (HAP and VAP) among burn patients, related in part to the patient and/or host factors, the causative pathogen, the severity of the pulmonary disease and other illnesses, as well as co-morbidities, will lead to wide variability in outcomes.7 A number of variables that have been identified as predictors of mortality in pneumonic burn patients must be considered, including severity of disease (necrotizing vs. non-necrotizing, number of lobes affected, presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome, bacteremia, severe sepsis, or septic shock), severity of illness (APACHE score), presence of organ dysfunction or failure, underlying diseases and co-morbidities, and specific causative organisms (MDR pathogen or not).8

Methods and materials

We conducted a prospective study of 80 patients admitted to the burn unit of Menoufia University Hospitals from September 2011 to March 2012. After obtaining ethical research approval from our hospital’s ethics committee and informed consent from the patients, the following patient data was gathered: name, age (those at the extreme end of the age range have bad prognosis), gender (females are more likely to suffer burn injuries), occupation, residence, marital status, special habits (cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug addiction), and past history of chest diseases (asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) predisposes patients to respiratory insufficiency). Chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and ischemic heart disease (IHD), can increase the mortality rate if associated with burns.

Following the gathering of patient history, a general examination was conducted to obtain: measurement of blood pressure, pulse, temperature and respiratory rate in order to identify the degree of hypovolemia and as a base line for progress of fluid intake. The level of consciousness was also examined to determine the degree of hypoxemia. First aid and early management began as soon as the burn patient arrived at the emergency room, and included the following: assessment of the patency of the air way, cervical immobilization in patients with distracted injuries, assessment of breathing by respiratory rate, chest wall motion, and auscultation, and assessment of blood circulation by level of consciousness, pulse rate, blood pressure, and capillary refill. Neurological evaluation, including determination of the Glasgow coma scale, pupil size and reactivity, was also performed. All clothing was removed to expose the burn and to prevent ongoing thermal injury. Patients with facial burns were carefully evaluated for smoke inhalation. As regards pre-hospital care, high oxygen by mask was delivered, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy was used for carbon monoxide (CO) toxicity. In the event of airway obstruction, this was administered intravenously. In the case of respiratory failure, patients had assisted ventilation or endotracheal intubation.

As well as the general examination, local examination was also conducted to assess: the type of burn (either physical (thermal, electrical or radiation) or chemical (acid, caustic or corrosives)), the extent of the burn (as a percentage), the depth of the burn (superficial or deep), the degree of sepsis if present, and any associated injuries if present. The respiratory system was also examined to assess any early symptoms of airway injury such as coughing, wheezing, hoarseness, change in voice, throat pain, and/or odynophagia, indicating severe upper airway injuries. This included assessment of any signs such as tachynpnea, paradoxical thoraco abdominal excursions, unstable breathing patterns or apnea, and asymmetrical movement of chest and crackles. Carbonaceous sputum is also regarded as a marker of exposure and should lead to transportation to a burn center for early endotracheal security. Use of accessory respiratory muscles should also be noted.

Laboratory studies were also conducted on patients to establish CBC (total leucocytic and differential cell count, hemoglobin and packed cell volume, red cell count and platelet count) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, chemistry profile, including liver function tests (albumen, bilirubin, prothrompine time and concentration). Laboratory tests also included random blood sugar, BUN and creatinine levels for baseline renal function in patients in shock or rhabdomyolysis, serum creatine kinase (CK) levels and, if appropriate, urine myoglobin in patients with large cutaneous burns, or prolonged immobilization. Electrolyte testing was conducted to identify anion gap acidosi. There was also routine analysis of blood gas, examination of sputum (gram stain, culture and sensitivity for aerobic and anaerobic organism, ZN stain for acid fast bacilli), and serological testing for atypical pneumonia when necessary. Bronchoscope can be diagnostic as well as therapeutic. Protected specimen brush and bronchalveolar lavage and c/s for detection of aerobic and an-aerobic organism were also performed as required. Evaluation was necessary to exclude extra-pulmonary sources of infection: blood cultures from two different sites, urine analysis and culture, and multiple swabs should be taken from the burns and sent for culture and sensitivity for aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Imaging studies included obtaining chest x-ray films (CXRs) in patients with a history of significant exposure or pulmonary symptoms.

Assessment of the severity of pneumonia to predict mortality was conducted via the CURB-65 criteria (confusion, urea>7 mmol/l, respiratory rate>30/min, blood pressure systolic<90mmHg, diastolic<60mmHg, and age 65>65 years). The risk of death increases as the score increases.2 The presence of 4 factors gives a mortality rate of 83%, 3 factors give 33%, 2 factors give 23%, while 1 factor gives 8%, and a mortality rate of 2.4% is obtained in the presence of no core factors. The pneumonia severity index score (PSI) is an alternative which is more sensitive, but complicated, and includes information on: age over 65 years and comorbid diseases (COPD, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, previous hospitalization within 1 year, suspicion of aspiration, altered mental state, post splenectomy state and chronic alcohol abuse or malnutrition). The physical findings are as follows: respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, DBP 60 mmHg or a SBP 90 mmHg, temperature >38.3º C (101º F), extrapulmonary sites of disease (presence of septic arthritis or meningitis), confusion and/or decreased level of consciousness. The laboratory findings are as follows: WBC <4,000/mcL or >30,000/mcL or Pao2 <60 mmHg or Paco2 of >50 mmHg on room air. Findings include the need for mechanical ventilation, serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dl or BUN >20 mg/dl (>7 mmol/L). Unfavorable chest radiographic findings are as follows: involvement of more than one lobe, presence of a cavity rapid radiographic spread and pleural effusion, hematocrit levels of <30% or hemoglobin <9 g/dl, evidence of sepsis or organ dysfunction as manifested by a metabolic acidosis, an increased PT, an increased PTT, decreased platelets, fibrin split products > 1:40, Na <130 mEq/L, and blood sugar >250 mg/dL. Patients are then ranked according to 5 categories of risk. From 1-5, these are 0.1%, 0.6%, 2.8%, 8.2% and 29.2% respectively.

Fluid resuscitation at the Menouyfia University Hospitals’ burn unit was conducted using the Evan Formula. The first 24 hours required 2 ml/kg/% of burn (Lactated Ringer’s solution) plus daily requirement of 5% glucose, and the following 24 hours required half the calculated volume used for the first 24 hours (Lactated Ringer’s solution) plus daily requirement of glucose (5%). All fluid was warm to avoid hypothermia. Open wound dressings were applied twice daily with micronized silver sulfadiazine in a hydrophilic base (dermazine) after hydrotherapy. Burn patients suspected of having pneumonia were placed on empiric antibiotic therapy, which is broad, covering gram positive, negative and anaerobes.

All data collected were tabulated and analyzed by Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) version 11 (using an IBM personal computer). Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviations (X±SD), and analyzed by applying a Student’s t-test. Qualitative data were expressed as numbers and percentages, and analyzed applying Chi-square and Z tests.

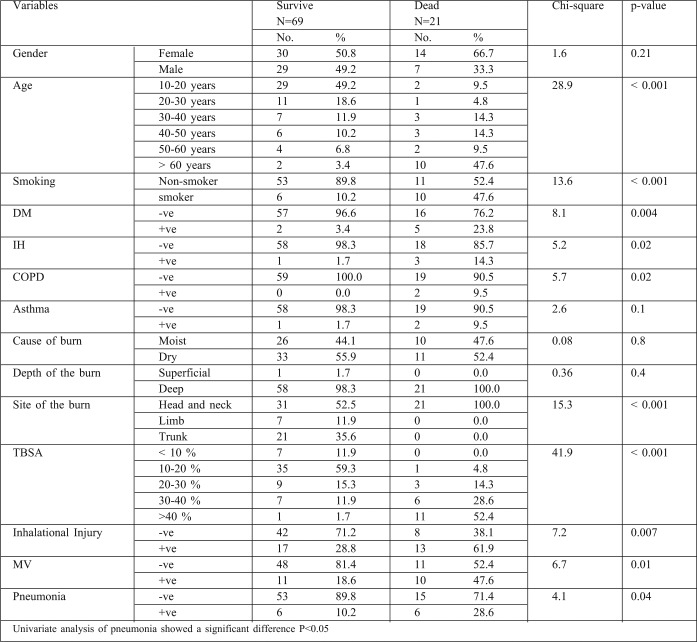

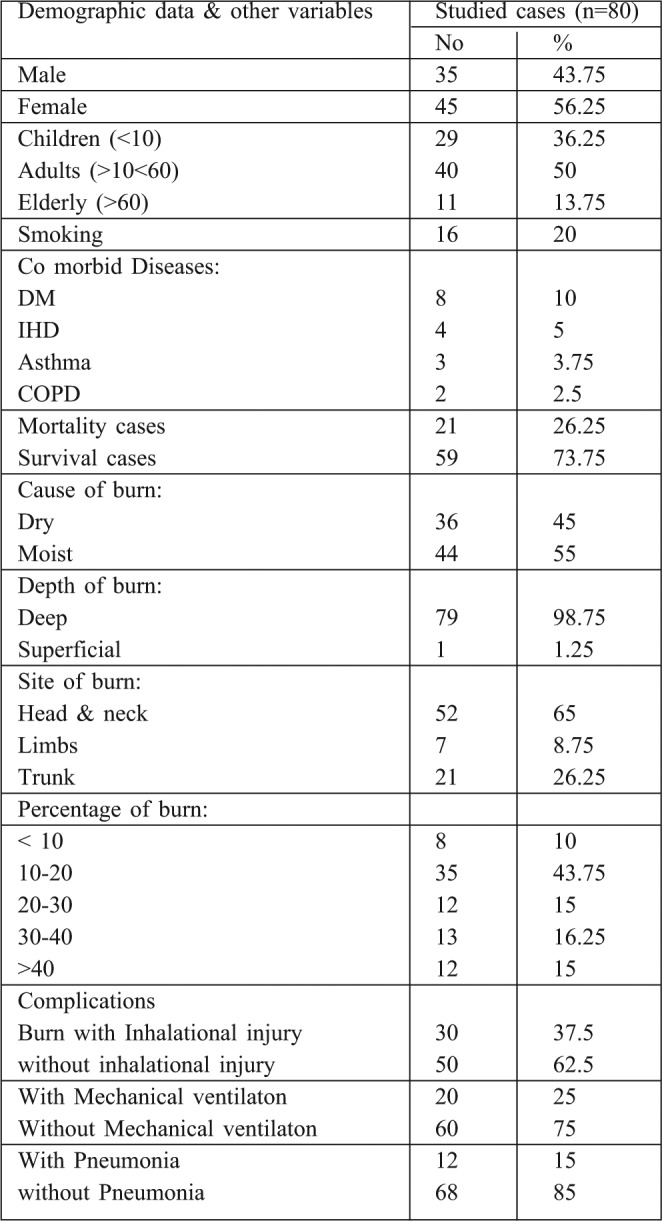

Table I. Demographic data and other variables of studied group.

Table II. Mortality rate of all burn patients.

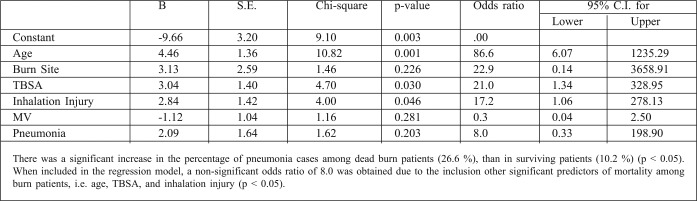

Table III. Regression model for the risk factors of mortality among burn patients.

Results

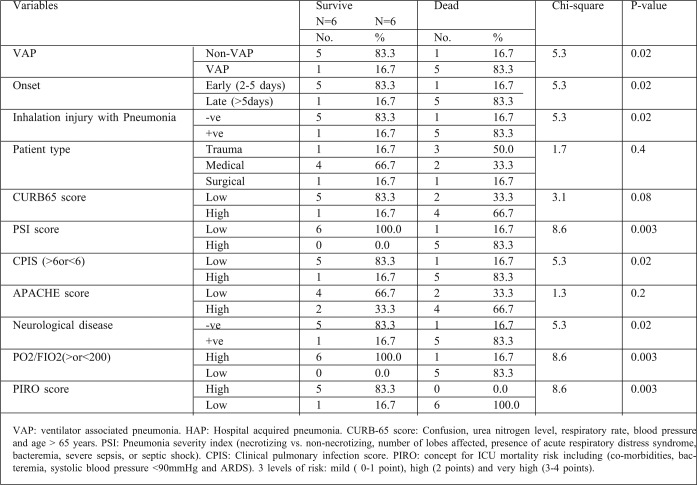

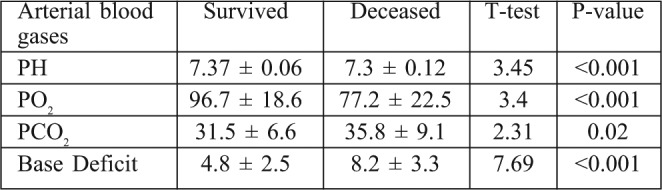

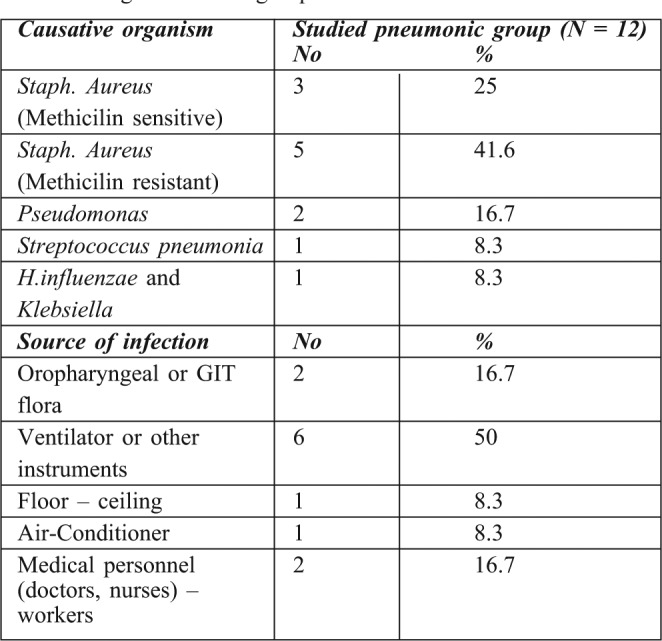

80 patients who fulfilled the criteria of the study were admitted to the Menoufiya University Burn Center from September 2011 to March 2012. Of these patients, 35 were male (43.75%) and 45 were female (54.25%), there were 44 children, 16 adults and 20 elderly patients. 36 (45%) patients were burnt by direct flame and 44 (55 %) suffered scald burns. 8 patients (10%) had burns of <10% of total body surface area (TBSA), 35 (43.75%) had burns of 10-20% TBSA, 13 (16.25%) had 30-40%, while 12 (15%) patients had >40% TBSA burns. Inhalation injury was identified in 30 patients (37.5%). 20 patients (25%) required mechanical ventilation. 12 patients (15%) experienced episodes of pneumonia. Comorbid diseases were also identified in several patients: 8 (10%) patients were diabetic, 4 (5%) had IHD, 3 (3.75%) were asthmatic, and 2 (2.5%) were COPD. The overall mortality rate was 26.25% (21 out of 80). The mortality rate among patients with pneumonia was 50% (6/12) compared with 23.3% (15/65) among non-pneumonic patients. Incidence of pneumonia was twice as high in the subset of patients with inhalation injury compared to those without inhalation injury (P< 0.001). All patients with pneumonia over the age of 50 died. The mortality rate of pneumonic burn patients in relation to the TBSA revealed that all patients with over 60% TBSA burns died. BD showed statistical difference between the survivors and non survivors group. Hypoxemia, hypercapnia and acidosis were also significant predictors of mortality among burn patients with pneumonia, and significant differences were noted in mortality for this specific type of pneumonia (VAP or HAP). Associated factors with significant correlation to the mortality rate of late onset pneumonia were severity of disease (APACHE score), presence of organ failure, co-morbidities, and VAP PIRO scores. Our data revealed that the incidence of microorganisms involved in pneumonic burn patients were Staph. aureus sensitive and resistant strains (25%, 41.6%) respectively, Pseudomonas (16.7%), Streptococcus pneumonia (8.3%) and H. influenzae and klebsiella (8.3%). The commonest sources of infection were mechanical ventilation and other respiratory equipment (approximately 50%).

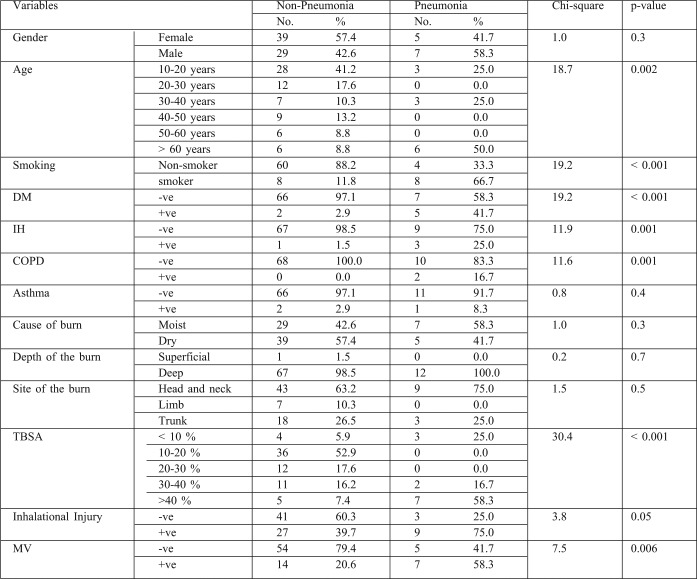

Table IV. Comparisons between pneumonic and non pneumonic groups as regard different variables.

Discussion

Nosocomial pneumonia affects 5-15% of hospitalized patients and can lead to complications in 25-33% of those admitted to burn units.9 Early detection and management of RTI is a good measure for lowering mortality in burn patients. During the period of our study, the overall burn patient mortality was 26.25% (21 out of 80). In another study of all patients admitted to Menoufiya University Hospitals’ Burn Center, Egypt, from January 2008 to January 2010, the mortality rate was 23.13% (65 out of 281).10 In a further study at the Alexandria Main University Hospital, Egypt, over a one year period (1999), the mortality rate was 33%.11 A retrospective analysis of 435 consecutive admissions to a regional burn unit in Saudi Arabia, over an 8 year period, found a case fatality rate of 7.4%.12 An analysis of mortality rates and related factors in a Spanish burn center, based on 710 patients treated between 1985 and 1988, found an overall mortality rate of 6.6%.13

The marked difference in mortality rates between our burn center and this latter one is due to the fact that the average burn size was <14% TBSA in almost all cases in the Spanish burn center. In another study, carried out from 1987 to 1990, 844 patients were admitted to the Grady Memorial Hospital Burn Unit, with a mortality rate was 8.5%.14 Half of all burns involved less than 10% TBSA, which explains the low mortality compared to that of our center. However, any measurement of outcomes in burn patients is useless and misleading unless the severity of injury is standardized. For many years it was accepted that the extent of the burn and the age of the patients were the two most important determinants of the probability of mortality in burn patients.15 It is now recognized, however, that smoke inhalation and pneumonia are important risk factors that must be included in the computation of mortality probability.16 In our study, the mortality rate among elderly patients in the >40 years age category, with variable burns, was 71.4% (15/21). Davis and his colleagues17 reported in their study that patients who succumbed to their injuries were older (P=0.005), had larger % TBSA burns (P<001) and required greater 24 hour resuscitative fluid (P=.002). In another study at the Menoufiya University Hospitals’ Burn Center from 2002 to 2004, involving 20 patients in the >45 years age category with variable burns, 9 patients died (45%).18 The difference in result compared to our study is related to the multiple predictors of mortality used in our studied elderly group, including inhalation lung injury, pneumonia, and multiple comorbid diseases (such as IHD, DM, asthma and COPD). This study found that the presence of pneumonia, MV, inhalation injury, increased bum size (>40%) and advanced age (>60 years) were all associated with increased mortality (P<0.01). This was in agreement with another study conducted at the Menoufiya University Hospital Burn Center from 2004 to 2008 (involving 61 males and 69 females). Inhalation injury, increased burn size and advancing age were all associated with increased mortality (p<0.01).19 The incidence of pneumonia in this study was 15% (12 out of 80). Overall mortality in patients with pneumonia was 50% (6 out of 12) compared with 22% (15 out of 68) for those without pneumonia. These statistical data clearly indicate that pneumonia is an important factor in burn patient mortality prediction.

Another study included an analysis of burn patients admitted to a burn care unit in Turkey, to identify the incidence of nosocomial infection in these patients. The study showed that among 182 burn cases, 169 of them met the inclusion criteria, of whom 75.1% acquired nosocomial infection and 15.7% acquired pneumonia.20 Our finding that pneumonia complication is associated with death in burn patients corroborates with that of McGowan et al.,21 who recently developed a mortality prediction model using NBR data. The overall mortality rate in pneumonic burn patients was 32%. The incidence of inhalation injury in this study was 37.5% (30 out of 80 patients were identified as having inhalation injury). Overall mortality in patients with inhalation injury was 46% (14 out of 30) compared with 14% (7 out of 50) for those without inhalation injury. A recent study at Menoufiya University Hospitals (Burn Unit and Chest Department) was carried out from 2008 to 2010; it included 130 burn patients with inhalation injury. The incidence of inhalation injury was 46.3% (130 out of 281). Overall mortality in patients with inhalation injury was 41.5% (54 out of 130), compared with 7.2% (1 out of 151) for those without inhalation injury.10 In Tokyo, Japan, a study performed to evaluate the impact of inhalation injury on burn patient mortality showed that between 1984 and 2002, of the 5560 patients admitted to 13 burns facilities of the Tokyo Burn Unit Association, 1690 patients (30.4%) had experienced inhalation injury. 21,22 The overall in-hospital mortality rate of patients with inhalation injury was higher than that of those without inhalation injury (33.6% vs 8.1%), which is close to the ratio of 2:3 found in our study. In another study of 710 burn patients in a Spanish burns center, it was found that the mortality rate among burn patients with inhalation injury was 66%.13 Although the contribution of inhalation injury and old age in the development of pneumonia in burn patients has been clearly outlined in two prior studies, as single center data were used, generalizations are less valid. Swenson et al.9 documented that the greatest concentration of death in both the sample and elderly aged pneumonic groups occurred within 72 hours of injury and decreased subsequently with no latter peak in mortality. This was in accordance with our findings, which showed the incidence of mortality to increase significantly where there is an early onset of pneumonia.

PrevalencePrevalence of DM, smoking, IHD, and COPD were significantly higher among pneumonic than non-pneumonic patients (p<0.001). Thombs et al.5 previously documented the effect of preexisting medical co-morbidities on burn-related mortality and length of hospital stay, but their study does not focus on other complications. However, El Gazzar et al.23 reported that diabetic burn patients are more likely to develop pneumonia. This can be explained by increased risk through aspiration, hyperglycemia, decreased immunity, impaired lung function, pulmonary microangiopathy and coexisting morbidities. Another study carried out on 498 burn patients in Germany, found smoking, cardiac diseases, and TBSA to be the strongest prognostic variables in pneumonic burn patients.24

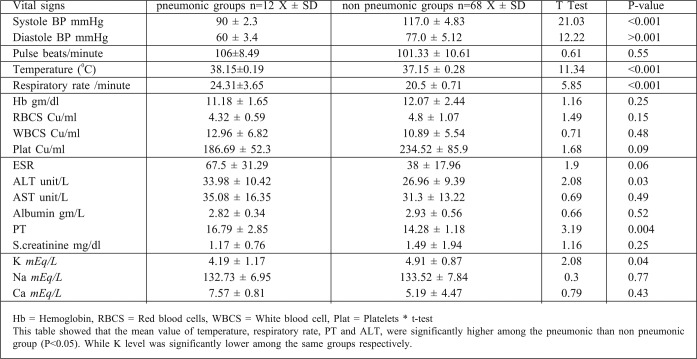

An American study found that COPD was one of the risk and prognostic factors of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated burn patients (P> 0.04).25 In another American study, IHD was found to increase the risk of pneumonia and pneumoniarelated death26 and BD showed statistical difference between survivors and non survivors. Hypoxemia, hypercapnia and acidosis were also significant predictors of mortality among burn patients with pneumonia. BD provides useful early parameters to predict the prognosis of burn patients with nosocomial pneumonia and, together with its change due to fluid resuscitation, provides additional information. From January to December 2008, a study was performed on 151 patients suspected of having hospital acquired pneumonia, admitted to a burn intensive care unit in Korea, which showed statistical differences between survivors and non survivors.27

A number of features related to the severity of pneumonia have been documented to impact on the outcome of HAP and/or VAP. Logistic regression analysis of 2 large clinical trials involving patients with suspected gram-positive nosocomial pneumonia determined the effect of treatment and other baseline variables on outcomes. Significant predictors of clinical cure in all patients with nosocomial pneumonia were an APACHE II score (p<0.01) single lobe pneumonia (p<0.01), absence of VAP (p<0.01), absence of oncology (p<0.01) and renal comorbidities (p<0.01) (110). In our study, APACHE II score, single lobar pneumonia, absence of VAP, absence of oncology and comorbidities, or low CPIS (clinical pulmonary infection score) were significant (p<0.02) statistical variables for prediction of cure in nosocomial pneumonia. Additional studies have shown the futility of the use of CPIS in burn patients. A study involving 158 burn patients revealed that the mean CPIS was 6.9 in patients with VAP, compared with a mean CPIS of 6.8 in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. 28 The poor performance of the CPIS in burn patients is problematic because VAP rates are currently highest in burn victims.29 Specific dependent predictors of increased mortality have been identified. It is well known that the presence of bacteremia in patients with VAP is associated with increased mortality.30 The PIRO concept for ICU mortality risk stratification in patients with VAP includes (1) comorbidities (COPD, immunocompromised state, heart failure, cirrhosis, or chronic renal failure), (2) bacteremia, (3) systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg, and (4) acute respiratory distress syndrome. On the basis of observed mortality for each VAP PIRO score, patients were classified into 3 levels of risk (1) mild (0-1 point), (2) high (2 points) and (3) very high (3-4 points).31 In the present work, mortality rate varied significantly according to VAP PIRO score, the severity of illness (measured as the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen),32 PSI, CURB-65 score, and organ dysfunction (p<0.001). For our study, we used 2 scoring systems of risk stratification for pneumonia: the CURB-65 score variables and the PSI. PSI score has been correlated with need for hospital admission, treatment and mortality risk.33 In this study, PT was significantly higher among adults and children (P<0.005) and the serum alanine amino transferase (ALT) was significantly higher among adults in comparisons between pneumonic and non pneumonic patients (P<0.05).

Another study carried out on pneumonic patients in an American burn care unit, 33 (38%) had prolonged PT and there were elevated ALT levels in 12 patients (36.4%).34 Our data revealed that microorganisms involved in pneumonia in burn patients were Staph. Aureus sensitive and resistant strains (25%, 41.6%) respectively, Pseudomonas (16.7%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (8.3%), H. influenza and Klebsiella (8.3%). The most common source of infection was mechanical ventilation (approximately 50%). Queenan and his colleagues reported that Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella species were the most prevalent organisms in pathogenesis accounted for approximately half of all organisms while Staphylococcus aureus was the most prevalent gram-positive organism. 35 Another study by Andrews et al. showed that ventilators are the most common exogenous source of infection in medical and surgical patients.36 The study was conducted at Erciyes University Burn Center during 2000 and 2009, based on the records of 1190 patients. Overall, 131 (11%) patients had 206 nosocomial infections with an incidence density of 14.7 infection /1000 patient days, and with Pseudomonas aeruginosa being the most frequent microorganism. 37 By contrast, Yasemin et al.20 reported that a total of 250 bacterial isolates were obtained from 179 burn patients, with the most predominant bacterial isolates being Actinobacter baumanni (23.6%) followed by coagulase negative Staphylococci (13.6%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12%), Staph aureus (11.2%) and E. coli (10%).

Table V. Comparison between pneumonic and non pneumonic groups regarding different clinical and laboratory variables.

Table VI. Blood gases of burn patients with pneumonia.

Table VII. Pneumonia indices among burn patients.

Table VIII. Microorganisms and sources of bacteria causing pneumonia among the studied group.

Study limitations

In reviewing this study, it is important to take into account its limitations. In particular, our regression model produced results which were not statistically significant due to the presence of other predictors of mortality among burn patients, such as TBSA and inhalation injury. The study would also have benefitted from an increased sample size and an extended duration of the study period.

Conclusions

Pneumonia is a common complication in adults hospitalized with burn injuries. 12 patients (15%) experienced episodes of pneumonia. Inhalation injury was identified in 30 patients (37.5%). 20 patients (25%) required mechanical ventilation. Co-morbid diseases were identified in 17 burn patients: 8 patients (10%) were diabetic, 4 (5%) had IHD, 3 (3.75%) were asthmatic, and 2 (2.5%) were COPD. The overall mortality rate was 26.25% (21 out of 80). Mortality rate among patients with pneumonia was 50% (6/12) compared with 23.3 % (15/65) among non pneumonic patients. The pneumonia was >two times higher in the subset of patients with inhalation injury than in the group of patients without inhalation injury (P< 0.001). BD showed significant difference between survivors and non survivors. Also hypoxemia, hypercapnia and acidosis were a significant predictor of mortality among the pneumonic group. There were attributed mortality associations with: late onset pneumonia, severity of disease and of illness (APACHE score) presence of organ failure, and comorbidity. The most common microorganisms involved in pneumonia in burn patients were: MSSA, MRSA, and Pseudomonas. The commonest sources of infection were mechanical ventilation and other respiratory equipment.

References

- 1.Celeste C, Hyunsu J, Herdi S, Sunder V. Proteomics improve the prediction of burns mortality: Results from regression split modelling. Clinical and translation science. 2012;5:243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2012.00412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shusterman DJ. Clinical smoke inhalation injury: Systemic effect. Occup Med. 1993;8:4679–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahn M, Sing W, Nazario S, et al. Increase blood lead level in sever smoke inhalation. Am J emerge Med. 2003;21:458–60. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam N, Kramer CB, Klein MB. Risk factors for the development of pneumonia in older adults with burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2011;31:105–10. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181cb8c5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Milner SM. Children under 4 years are at greater risk of mortality following acute burn injury: Evidence from national sample of 12,902 paediatric admission. Shock. 2006;26:348. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000228170.94468.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice HE, O’Keefe GE, Helton WS. Morbid prognostic Features in burned patients. Archives of surgery in university Affiliated Hospital, Chicago. 1997;132:880–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430320082013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rue LW, Cioffi WG, Mason AD, et al. Improved survival in burned patients with inhalation injury. Arch Surg. 1999;128:772–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420190066009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todd F, James M. Ventilator associated pneumonia in burn patient: A cause or consequence of critical illness. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2011;5:663–73. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson JW, Otto A, Gibran NS, et al. Trajectories to death in patients with burn injury. J of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2013;74:282–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182788a1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Helbawy RH, Ghareeb FM. Inhalation injury as prognostic factor for mortality in burn patients. Ann. Burns and Fire Disasters. 2011;24:82–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attia AF, Reda AA, Mandil AM, et al. Predictive model for mortality and length of hospital stay in an Egyptian burns center. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:1055–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Shalash S, Warnasuriya ND, Al-Shareef Z. Eight years’ experience of a regional burns unit in Saudi Arabia: Clinical and epidemiological aspects. Burns. 1996;22:376–80. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benito-Ruiz J, Navarro-Monzonis A, Beana-Monatilla P, et al. An analysis of burn mortality: A report from a Spanish regional burn centre. Burns. 1991;17:201–4. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(91)90104-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renz BM, Sherman R. The burn unit experience at Grady Memorial Hospital: 844 cases. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1992;13:426–36. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heimbach DM, Waeckerle JF. Inhalation injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1316–20. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomellini V, Fauce DE, Gomez CR, Kovacs EJ. An age associated increase in pulmonary inflammation after burn injury is abrogated by CXCR2 inhibition. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1403–1501. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis CS, Albright JM, Carter SR, et al. Early pulmonary immune hypo responsiveness is associated with mortality after burn and smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care and Research. 2012;33:26–35. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318234d903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fergany Ahmed. Prediction and Risk factors of mortality in burn patients in Menoufia University Burn Center. 2005. p. 113. Thesis of MSc degree in General Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmoneam Abd. Inhalation injury as a prognostic factor for mortality in burned patient. 2005. p. 105. Thesis of MSc degree in General Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayram Y, Parlak M, Aypak C, Bayram I. Three year review of bacteriological profile and anti biogram of burn wound isolation in Van, Turkey. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:19–23. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGowan G, George RL, Cross JM, Rue LW. Improving the ability to predict mortality among burn patients. Burns. 2008;34:320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki M, Aikawa N, Kobayashi K, et al. Prognostic implications of inhalation injury in burn patients in Tokyo. Burns. 2005;31:331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Gazzar H, et al. Value of tracheal aspiration in the diagnosis of bacterial infection in mechanically ventilated patients. Menoufia University; 2006. p. 89. MSC thesis chest department Menoufia University. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Germann G, Barthold U, Lefering R, et al. The impact of risk factors and pre-existing conditions on the mortality of burn patients. Burns. 1997;23:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres A, Aznar R, Maria J, et al. Incidence, risk, and prognostic factors of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients. The American Thoracic Society. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1990;142:523–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiovula I, Sten M, Pirjo H, et al. Risk factors for pneumonia in the burned elderly patients. The American Journal of Medicine. 1994;96:313–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho YS, Yang HT, Yim H, et al. Serum lactate and Base Deficit: Early predictors of morbidity and mortality in burn patients with inhalation injury. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80:84–9. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System: National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004. Am J Infect control. 2004;32:470–85. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Andrus ML. National health care safety network report. Am J Infect Control. 2009;36:609–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Fabian TC. EPO Critical Care Trials Group: Efficacy and safety of epoetin alfa in crirically ill patients. N EngL J Med. 2007;375:965–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lisboa T, Diaz E, Sa-Bonges M, et al. The ventilator-associated pneumonia PIRO Score: A tool for predicting ICU mortality and health care resource use in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2008;134:1208–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Combes A, Luyt CE, Fagon Y. Early predictors of infection recurrence and death in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:146–154. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000249826.81273.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. AM J Med. 2005;118:384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daxboeck F, Gattringer R, Mustafa S, et al. Elevated serum Alanine aminotransferees’ levels in patients with pneumonia. Clin Microbiol. 2005;11:507–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Queenan AM, Foleno B, Gownley C, et al. Effects of inoculum and 13- lactamase activity in Amp and extended-spectrum 6- lactamase (ESBL)- producing Escherichia coli and klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolated tested by using NCCLS ESBL methodology. Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:269–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.269-275.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johanson WG, Seidenfeld JJ, Gomez P. Bacteriologic diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia following prolonged mechanical ventilation. AM Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:259–64. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alp, Emine, Coruh, Atilla, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia infection and mortality in burn patients 10 years of the experience at University Hospital. J of Burn Care & Research. 2012;3:379–85. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318234966c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]