Abstract

Background:

Gender role attitudes toward sexual matters may define suitable and appropriate roles for men and women during a sexual relationship. This study aimed to explore and assess gender-based sexual roles in Iranian families.

Materials and Methods:

This was an exploratory mixed methods study in which perceptions and experiences of 21 adult Iranian participants about gender-based sexual roles have been explored in three provinces of Iran in 2010-2011, to generate items for developing a culture-oriented instrument to assess gender role attitudes. The developed and validated instrument, then, was applied to 390 individuals of general population of Tehran, Iran in 2012.

Results:

In content analysis of the qualitative phase data, four categories emerged as the main gender-based sexual roles: Decision making, relationships, care, and supervision and control. After passing the stages of item reduction, seven items remained for the instrument. In the quantitative phase, results showed that most of the participants (78.9%) believed in shared sexual roles for both genders. Consideration of a sexual role as “entirely masculine” or “preferably masculine” was the second prevalent attitude in 71.43% of gender-based sexual roles, whereas “entirely” or “preferably feminine role” was the second next most dominant attitude (14.28%).

Conclusions:

The results of the present study have revealed some new gender-based sexual roles within Iranian families; which may be applicable to show the capacity for achieving some domains of reproductive rights in Iran.

Keywords: Attitude, gender role, Iran, sexuality

INTRODUCTION

Reproductive rights are one of the sub-domains of reproductive health[1] and act as the foundation for the development in a society.[2] In a paragraph of these rights, which is associated with the domain of marriage and familial relationship, men are asked to accept responsibilities and to have commitments in provision of reproductive health equal to women and to cooperate with their spouses in different stages of their marital life.[1]

Based on this issue, socially approved and accepted behaviors of women and men in their family life through which they acquire their gender-based roles can be suggested as an indicator to manifest this dimension of reproductive rights. Gender roles are normative behaviors and attitudes that are expected from individuals based on their biological sex.[3] These roles have a vast concept based on which numerous responsibilities and assignments in the family are defined, as the meaning of gender role is the definition of manhood and womanhood in a society.[4] Gender role attitudes reflect individuals’ attitudes concerning appropriate role activities for men and women and contain the general concept from gender-based roles such as gender-related duties in the family.[5] Numerous researchers have investigated the importance of gender role attitudes and their effect on various dimensions of human behaviors such as domestic violence and health promotion behaviors.[6] Research showed that having egalitarian attitudes in gender roles can lead to some outcomes like increased feeling of self-efficacy in women and men,[7] more adaptation in marital life,[8] decreased number of requests by men for divorce,[9] increased participation of spouses in taking care of children,[10] increased employment and income of women,[11,12] decreased suicidal thoughts,[13] and decreased inter-generational gaps.[14] Meanwhile, some of the gender role attitudes in the family are associated with couples’ sexual affairs.

Sexual affairs are considered as one of the most important domains of reproductive health and quality of life in the family.[15] In Islam, sexual relationship has been considered as a part of human's identity, so achieving mutual satisfaction among the couples has been emphasized.[16]

Achievement of sexual satisfaction is of great importance for the couples, and increased sexual satisfaction is accompanied with increased satisfaction among the couples in their marital life globally.[17] Ability to have an informed pleasant and safe sexual life is based on positive expression of sex specifications and reciprocal respect of men and women in their sexual relationship.[18] Non-sexual interactions between sexual partners[19] and inappropriate attitudes and beliefs toward sexual issues have notable effect on the incidence of sexual dysfunctions.[20]

Gender role attitudes in the domain of sexual affairs represent appropriate role activities for men and women during their sexual relationship. Research showed that having egalitarian gender role attitudes can lead to improvement of sexual function, increase of satisfaction in marital life among men and women,[21,22,23] promotion of mental health, and a better relationship with the sexual partner.[5] Existing international instruments that are used to measure gender role attitudes often pay less attention to sexual affairs domain.[24,25,26,27] Attitudes toward Women Scale[28] and Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale,[29] which have considered these roles in some items, indicate the sexual relationship out of the marriage, which is not acceptable in Iranian Islamic culture.

There is consensus on the fact that gender role attitudes are absolutely culture based and different in each society;[30] therefore, the instrument to measure them should be designed accordingly. A measurement tool in research should coincide with the mental realities of its respondents, so as to be perceived the same way the researcher intends.[31] Considering the fact that gender role attitudes are culture oriented and due to the importance of these attitudes in couples’ sexual affairs domain and lack of a questionnaire adapting to Iranian culture, the researchers decided to primarily explore various aspects of partners’ gender-based roles in sexual affairs in Iranian families in a qualitative study, and then generate the items to measure gender role attitudes in this domain and assess these attitudes in the study population quantitatively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study is a part of a greater exploratory mixed methods study which aimed to explore and assess gender role attitudes in all domains of Iranian family life. The present article reports gender role attitudes in the domain of Iranian couples’ sexual affairs. In an exploratory mixed methods study, the goal is that the primary results, obtained by the first method (qualitative), can develop and form the second method (quantitative). This design is especially helpful when the researcher needs to develop an instrument, or needs to detect important variables of a domain due to unavailability of an appropriate instrument or the unknown variables effective on an outcome. In this type of research, the quantitative phase is consequently conducted after ending the qualitative phase and based on its findings.[32]

With regard to ethical considerations of the project, this study firstly received the approval of the related university ethical committee (No. 89.D.130/676), and based on their recommendations, qualitative interviews and quantitative sampling were administered by interviewers of the same gender as that of the participants.

In the first qualitative phase of the present study, researchers explored participants’ perceptions and experiences about gender-based roles in the domain of couples’ sexual affairs through the content analysis method. In this phase, purposeful sampling with maximum variations was conducted on Iranian women and men ≥ 20 years who were married at the time of the study.

In order to achieve maximum variations among the participants, they were selected so as to have the highest variations concerning their age, education level, job categories, duration of marital life, and the number of children. Men and women were selected in every other gender, in order to have a balance in the number of male and female participants and to have various perceptions and experiences of both genders. Participants were firstly selected among the individuals accessible to the researchers; then, snowball method was adopted to select the rest of participants. Sampling continued until data saturation. In a qualitative research, data collection goes on until the participants yield either little new data or repeat their previous ideas.[33] In this phase, semi-structured individual interviews and focus group discussions were conducted for the participants to collect the data. The interviewers of the same gender as that of the participants (two principal researchers) conducted the interviews and group discussions. Focus group discussions were held in five-member groups with an identical gender, and the participants, as mentioned before, were selected with maximum variations. At the beginning of the present study, individual interviews were conducted, and then, in order to be sure that the existing interaction in group discussions could lead to collection of new data, focus group discussions were adopted. The interviews were held in the participants’ houses, researchers’ offices in the faculty, health care centers, or a research center, based on participants’ agreement and preference.

After getting a written informed consent from the participants, all interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Conventional content analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data.[34] In this type of analysis, the researcher inductively and just based on research data begins coding process of the interviews’ transcriptions.

In the qualitative phase of the present study, data analysis was conducted concurrently with data collection. In order to verify the rigor of data in this phase of study, criteria of credibility and dependability of the data were used. For credibility of the findings, we used member checking; and for dependability, two principal researchers (a female and a male) conducted the interviews with the women and men, respectively. They independently coded all of the transcriptions, and the cases concerning the lack of consensus were modified through consultation. A part of the transcriptions was independently recoded by an external evaluator out of research team, and the cases concerning the lack of consensus were modified through face-to-face discussions.

After the qualitative phase ended, the findings of this phase were used to generate some items to assess the research subject quantitatively. These items underwent stages of face validity (through a pretest on female and male individuals selected from general population of Tehran), content validity (with approval of 10 experts in courses of reproductive health, maternal and child health, psychology, psychiatry, and health education and promotion) and structure validity (through testing in general population of Tehran). For testing the reliability of items, the test–retest method was adopted. As the stages of scientific validity and reliability of the instrument have been conducted for our broader study to explore and assess gender role attitudes in all domains of family life, and the details related to instrument developing are out of the objectives of the present article, they are not mentioned in this paper.

In the quantitative phase of the study, which was conducted on the general population of Tehran, (Iranian women and men ≥ 20 years), the sample size was calculated to be 385 subjects based on the following formula and significance level of 0.05 (Z = 1.96, δ =66, d = 6.6), and thus, a total of 400 subjects were considered to avoid non-sampling errors.

Firstly, 80 blocks were selected through quota sampling from the city, which were assigned to women (n = 40 blocks) and men (n = 40 blocks). In each of the blocks, using systematic sampling, five families residing in the block were selected and the respondent in each family was selected through quota sampling, so that age distribution of the subjects matched the general population. Findings of this phase were analyzed by SPSS version 16.

RESULTS

In the qualitative phase of the present study, 21 participants (11 women and 10 men) residing in three provinces of Iran who were accessible to the research team due to either the researchers’ location of study or their working in these provinces (Tehran, Semnan, or Khorasan Razavi) were selected during 2010-2011 and sampling ended by data saturation.

Participants’ age ranged 21-66 years. Their levels of education varied from high school diploma to PhD. The participants were from different job categories (workers, employees, managers, homemakers, retired, self-employed, students, etc.). Their marital life duration ranged 1-36 years, and their number of children ranged 0-3. After categorizing the codes obtained by content analysis of the qualitative data of the present study, based on their similarities and dissimilarities, four categories emerged for couples’ roles in the domain of sexual affairs, i.e. decision making, relationships, care, and supervision and control. For instance, one of the participants whose narrations led to emergence of the category of “decision making” stated:

“Their decision making about when to have sexual intercourse and when not to have is very important. You see, there are some books recommending when (a certain time) to be conceived and when not to be. The man should notice this. He should consider his spouse's physical and psychological status, and then … does that; of course if his spouse desires.” (21-year-old female student with no children)

Another participant whose narrations were placed in the category of “relationships” said:

“The husband and wife should not be in disguise in their sexual affairs. They should absolutely express the things, which bother them or can better their relationship …. they can express that before … or at the time when it occurs … they should not leave it unmentioned…” (39-year-old female employee with one child)

Another participant whose narrations led to emergence of the category of “care” stated thus:

“It is not right that one partner emotionally cares about his/her spouse and the other one not. For example, one says I do this as I like my husband … to be satisfied or to enjoy more. If so, one can upmost tolerate something against her desire for one year, two years or six months but not longer. Our personality has been formed and we cannot ignore our expectations…. It leads to problems in long term … we (the spouses) should be careful about each other.” (48-year-old male employee with two children)

The emerged codes from another participant's narrations were categorized in “supervision and control” category. She said thus:

“I like they honestly declare anything about genital infections to each other, the husband to his wife or the wife to her husband. After being honest to each other and understanding their sexual problems, they should check it whether they followed treatment correctly or not, or check whether the partner follows up the physician's order or not. If they should not have an intercourse or consume any medication … they should be careful about each other and indicate that.” (49-year-old female homemaker with two children)

After ending the qualitative phase of the study, the emerged codes were written in the form of items of a questionnaire. Out of 21 items that emerged from the qualitative phase of the study, 7 items remained after item reduction stages, which were used in the quantitative questionnaire.

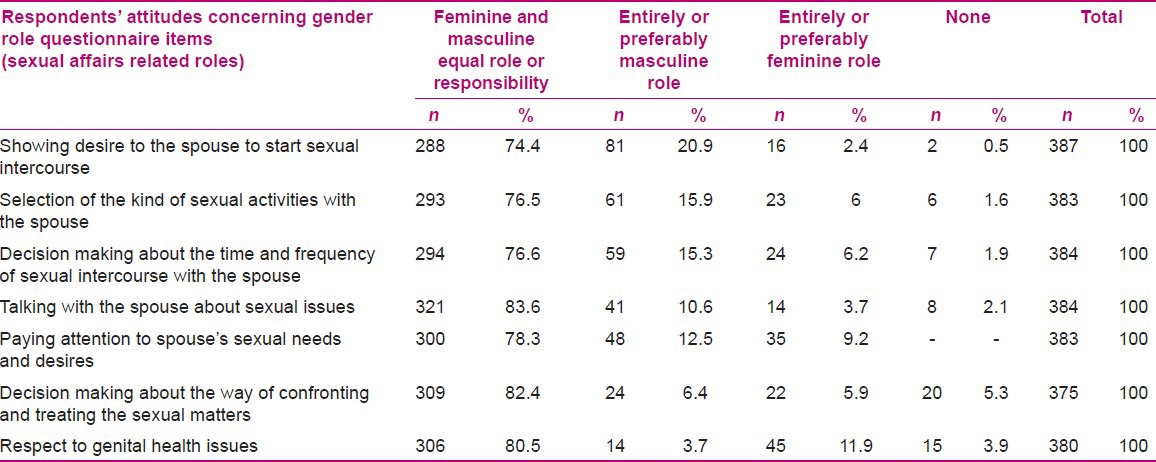

Individuals’ attitudes concerning the gender-based division of these roles with a six-option spectrum of responses [entirely feminine, preferably feminine, masculine and feminine with equal role and responsibility, preferably masculine, entirely masculine, and neither feminine nor masculine: (no one should do it as it is not a correct action)] were investigated [Table 1].

Table 1.

Items related to couples’ gender-based sexual roles

After administration of the questionnaire to the general population residing in 22 urban districts of Tehran in 2012, 390 questionnaires were collected to enter data analysis stage.

The subjects comprised 195 women and 195 men. Their age ranged 20-76 years (mean age 38 years and SD = 13.25) and their education level varied from illiteracy to a university degree. A total of 270 subjects (69.2%) were married and their number of children ranged 0-7.

The findings of the quantitative phase of the present study showed that most of the subjects (78.9%) believed that the spouses should mutually play all the sexual role in their marital life. In five cases of these roles, the subjects’ second most dominant attitude was superiority or monopoly of masculine role (71.43%), while in one case of these roles, the item of “respect to genital health issues,” the attitude of being entirely feminine ranked second among the respondents’ attitudes (14.28%). The detailed results of subjects’ attitudes have been presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of gender role attitudes in the domain of couples’ sexual affairs

With regard to investigation of the association between respondents’ demographic characteristics and their type of gender role attitude in sexual affairs, the analysis of the data through Chi-square test (in significance level of 0.05) showed that subjects’ attitudes concerning the roles of “talking with the spouse about sexual issues” were associated with the subjects’ gender (P = 0.01) and level of education (P = 0.02). Subjects’ attitude about the role of “paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires” was associated with their level of education (P = 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The research on gender differences in sexual affairs domain approved four issues related to the difference between women and men in their sexual affairs, i.e., higher sexual desire among men compared to women, more emphasis by women on having sexual relationship based on commitment to the sexual partner, more sexual aggression and invasion of men, and higher flexibility of women's sexual affairs in response to various cultural, social, and situational factors.[35]

Another research showed more sexual activities and more qualified sexual life among men compared to women, and such differences increase by age.[36]

The present study is in line with the previous studies in the detection of gender-based differences among women and men in their sexual affairs, exploring gender-based roles related to such affairs in Iranian families, and through this exploration, suggesting and validating some items to be added to the existing instruments for measuring gender role attitudes.

The existing international instruments used to measure gender role attitudes have often paid little attention to the division of gender-based roles associated with the domain of sexual affairs.[24,25,26,27] Attitudes toward Women Scale[28] and Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale,[29] which have considered these roles in some items, pointed to the sexual relationship out of marital range, which is not acceptable in Iranian Islamic culture.

In the qualitative phase of the present study, seven items emerged to measure gender role attitudes in sexual affairs domain, i.e., showing desire to the spouse to start sexual intercourse, selection of the kind of sexual activities with the spouse, decision making about the time and frequency of sexual intercourse with the spouse, talking with the spouse about sexual issues, paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires, decision making about the way of confronting and treating the sexual matters, and respect to genital health issues.

In the study of Refaie Shirpak et al. conducted in Tehran (2007),[37] based on the findings of the qualitative phase, a questionnaire was developed for need assessment among women in the domain of sexual health education. The third part of their questionnaire, which contained questions on attitudes toward sexual health, consisted of six attitude domains. We believe that three of these six domains were comparable and consistent with the items emerged in our study. Their three obtained domains included:

Talking and discussing with the spouse about sexual issues

The possibility of suggesting a sexual intercourse from the side of women

Shared sexual satisfaction and pleasure between spouses.

The latter domain seemed to be similar to our “paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires” item.

Simbar et al. (2004) conducted a study on female and male university students in Ghazvin, Iran, and reported some gender differences in the domain of sexual behaviors. They reported gender to be the most independent factor effective on teenage university students’ sexual behavior. Also, in their study, a gender difference was observed in subjects’ perception of intensity and outcomes of venereal diseases and AIDS, and its effect on their life, work, and social communication.[38] These findings seems to be comparable with “respect to genital health issues” obtained in the present study. No items similar to the remaining items obtained in the present study were found in the available research.

With regard to the findings of the quantitative phase of the present study, although in the investigation of all questionnaire items, most of the subjects believed in mutual responsibility of the women and men to play various gender-based roles, in five items out of seven, related to sexual affairs, the second dominant attitude among the respondents was the belief in entirely or preferably masculine role in couples’ sexual affairs [Table 2].

With regard to the role of “showing desire to the spouse to start a sexual intercourse,” Peplau (2003) reported that men typically pioneer to express the sexual desire to women.[35] In the study of Hashemi et al. (2013) conducted on married women referring to Taleghani Health Care Center in Tehran, it was declared that in 66% of the subjects, men either “always” or “often” started the sexual activity.[39] In the study of Ziaee and Khoury (2006) on working married women who had at least one child residing in Gorgan, Iran, it was reported that only 0.6% of women “always” started sexual activity, while 38% of them only “sometimes” suggest having sex.[40] The findings of the quantitative part in the study of Refaie Shirpak et al. (2007) in Tehran reported that women had a positive attitude about the reciprocality of sexual affairs. They revealed the fact that women can initiate a sexual relationship,[37] but the result of their qualitative phase of research (2010) showed that the studied women did not believe that their initiation of sexual activities was applicable and claimed that their spouses might have an unexpected reaction to this issue.[41] As our study investigated the women's and men's attitude concurrently and revealed that most of the subjects from both genders believed in equality of women's and men's responsibility and role to manifest their desire to start a sexual activity, it seems that efficient steps should be taken to modify unrealistic concerns of some women in relation with their spouses’ inappropriate reaction toward their sexual desire expression.

With regard to “talking with the spouse about sexual issues,” although in our study, most of the subjects believed in an equal role for women and men, a significant association was observed between subjects’ gender and their attitudes; so that men believed this role to be more “masculine” compared to women. In this regard, Impett and Paplau (2003) reported that sexual interactions need both sexual partners to coordinate their preferences and functions with each other.[42] In the qualitative study of Refaie Shirpak et al. in Tehran (2010), all participants (both reproductive health providers and clients) emphasized on the inadequacy of couples’ communication concerning sexual issues.[41] Moshiri et al. (2004) also reported that unfortunately in Iranian culture, sexual issues are a taboo and it is a rare occurrence that the couples talk about them.[16] Ziaee and Khoury in a study in Gorgan (2006) on married working women showed that 14% of the subjects never talked about sexual issues with their spouses.[40] Lack of communication among the couples can lead to misunderstandings and dissatisfaction with their relationships. This issue can prevent talking about and reaching an agreement on the manner and quality of sexual relationship among the couples,[41] which is consistent with the finding of the present study (“selection of the kind of sexual activity with the spouse” and “decision making about the time and frequency of sexual intercourse with the spouse”). On the other hand, this issue is important, as one of the characteristics of healthy sexual behavior is mutual agreement on sexual activity. Talking with the spouse concerning sexual issues can help her to express her reason for not doing the activities she does not like or desire to do.[37] It seems that the struggle to change the attitudes of some men related to talking about sex and empowerment of women to negotiate with their spouses on sexual affairs is one of the important interventions for which the present study can create an appropriate background.

With regard to the role of “paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires,” our findings revealed that most of the subjects believed in women and men having equal responsibility in this role. In this regard, Refaie Shirpak et al., in a qualitative study in Tehran (2010), revealed that in some women's viewpoint, sexual pleasure is just for men and women have no rights in this issue.[41] As the findings of a qualitative study cannot be generalized, there is no inconsistency between the present study and their study. In addition, in our study, 9.2% of the subjects also believed in dominancy or monopoly of women's role concerning paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires, which reflects the priority to provide the men with satisfaction in sexual affairs from their viewpoint. However, it seems that this problem exists in Iranian society more or less and appropriate educational interventions are needed to modify these attitudes.

With regard to the role of “respect to genital health issues,” as the second dominant attitude among the subjects in our study, the priority or monopoly was for women (11.9%). This finding is a notable point of the present study as it seems that the mutual nature of sexually transmitted infections is sometimes forgotten, and due to more overt disease manifestations among women, the prevention or treatment of the disease may be considered more as a feminine responsibility. Education of organized principles of sexual health seems to solve this problem.

With regard to the association between subjects’ gender role attitudes in the domain of sexual affairs and their level of education, our findings revealed a significant association between these two variables, so that individuals’ higher level of education was accompanied with the increase of their belief in women's and men's shared responsibility in roles such as “paying attention to spouse's sexual needs and desires” and “talking with the spouse about sexual issues.” This finding is consistent with the general characteristics expected from gender role attitudes. Arends-Toth et al. (2007),[5] Hoffman and Kloska (1995),[24] and Kiani et al. (2009)[4] approved the association between higher level of education and subjects’ more egalitarian gender role attitudes.

CONCLUSION

This study extended previous research on gender role attitudes by exploring gender-based roles in the domain of sexual affairs in Iranian families, and through this exploration, suggesting and validating some items to be added to the existing instruments for measuring gender role attitudes.

Finally, the researchers of the present study hoped to define the existing capacities to achieve some dimensions of reproductive rights in Iranian families. In addition, they tried to make a background for further research related to gender roles in Iranian and other similar cultures.

With regard to the limitations of the study, firstly, this study explored gender-based roles in sexual affairs domain just among healthy couples, while if one or both spouses suffer from a chronic physical or mental disease, their accepted and expected roles are likely to change and new role domains can be explored. Secondly, in the present study, the age difference between couples was not considered in the exploration of gender-based sexual roles, but the range of age difference among the couples may be effective on these roles. It is suggested to include these points in future studies to be able to reveal other possibly existing gender-based sexual role domains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financially supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences. We would like to thank Dr. Zahra Behboodi Moghaddam for the meticulous external evaluation of the study codes, categories, and themes. We are grateful to the questioners of Iranian Students Polling Agency (ISPA), who collected the data for the quantitative phase of our study. Finally, we are indebted to the study's participants for sharing their valuable attitudes, perceptions, and experiences with us.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was financially supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soltani PR, Parsay S. Tehran: Sanjesh Takmili Publications; 2009. Maternal child health. Book in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNFPA. 2009. Reproductive Rights: Advancing Human Rights. [Last retrieved 2009 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/rights/rights.htm .

- 3.Ben-David S, Schneider O. Rape perceptions, gender role attitudes, and victim-perpetrator acquaintance. Sex Roles. 2005;53:385–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiani Q, Bahrami H, Taremian F. Study of the attitude toward gender role on submit gender egalitarianism among university students and employees in Zanjan. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2008;17:71–8. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arends-Toth J, Fons JR, Vijer VD. Cultural and gender differences in gender role beliefs, sharing household task and child care responsibilities, and well-being among immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands. Sex Roles. 2007;57:813–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katenbrink J. Translation and standardization of the Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale (SRES-B) on a German sample. Sex Roles. 2006;54:485–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan T, Selmon N. Race and gender differences in self-efficacy: Assessing the role of gender role attitudes and family background. Sex Roles. 2008;58:822–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X, Lai SC. Gender ideologies, marital roles, and marital quality in Taiwan. J Fam Issues. 2004;25:318–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufman G. Do gender role attitudes matter? Family formation and dissolution among traditional and egalitarian men and women. J Fam Issues. 2000;21:128–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman CD, Moon M. Women's characteristics and gender role attitudes: Support for father involvement with children. J Genet Psychol. 1999;150:411–8. doi: 10.1080/00221329909595554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigall EA, Konrad AM. Gender role attitudes and careers: A longitudinal study. Sex Roles. 2007;56:847–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stickney LT, Konrad AM. Gender role attitudes and earnings: A multinational study of married women and men. Sex Roles. 2007;57:801–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt K, Sweeting H, Keoghan M, Platt S. Sex, gender role orientation, gender role attitudes and suicidal thoughts in three generations-A general population study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:641–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks JL, Lam CB, Mchale SM. Family patterns of gender role attitudes. Sex Roles. 2009;61:221–34. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization: Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health. [Last retrieved on 2002 Jan 31]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/defining_sexual_health/en/index.html .

- 16.Moshiri Z, Mohaddesi H, Terme Yosefi O, Vazife Asl M, Moshiri SH. Survey of education effects on sexual health in couples referred to marriage consultation centers in west Azarbayjan. J Urmia Nurs Midwifery Fac. 2004;2:135–42. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakmar E. The predictive role of communication on the relationship satisfaction in married individuals with and without children and in cohabiting individuals: The moderating role of sexual satisfaction. [Last retrieved on 2013 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.metu.edu.tr .

- 18.Hasanzadeh BM. Effective factors on women's sexuality. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertility. 2006;9:86–92. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowe M. Couple therapy and sexual dysfunction. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1995;7:195–204. doi: 10.3109/09540269509028322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehrabi F, Dadfar M. The role of psychological factors in sexual functional disorders. Iran Psychiatry Clin Psychol. 2003;9:4–11. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefer AK, Sanchez DT. Scripting sexual passivity: A gender role perspective. Pers Relatsh. 2007;14:269–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patrick S, Sells JN, Giordano FG, Tollerud TR. Intimacy, differentiation, and personality variables as predictors of marital satisfaction. Family J. 2007;15:359–67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarzwald J, Koslowsky M, Izhak-Nir EB. Gender role ideology as a moderator of the relationship between social power tactics and marital satisfaction. Sex Roles. 2008;59:657–69. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman LW, Kloska DD. Parents gender-based attitudes toward marital roles and child rearing. Sex Roles. 1995;32:273–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apparala ML, Reifman A, Munsch J. Cross-national comparison of attitudes toward father's and mother's participation in household tasks and childcare. Sex Roles. 2003;48:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang L. Gender role egalitarian attitudes in Beijing, Hong Kong, Florida and Michigan. J Cross Cul Psychol. 1999;30:722–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swim JK, Aikin KJ, Hall WS, Hunter BA. Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spence JT, Helmreich R, Stapp J. A short version of the Attitudes toward Women Scale (AWS) Bull Psychometr Soc. 1973;2:219–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beer CA, King DW, Beer DB, King LA. The Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale: A measure of attitudes toward equality between the sexes. Sex Roles. 1984;10:563–76. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu L, Xie D. The relationship between desirable and undesirable gender role traits, and their implications for psychological well-being in Chinese culture. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44:1517–27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun M. Using egalitarian items to measure men's and women's family roles. Sex Roles. 2008;59:644–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. 2nd ed. California, London, New Delhi: Sage Publication; 2007. Designing and conducting Mixed Methods Research. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Firmin MW. New York: Sage Publications; 2008. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 24]. Themes. The Sage Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Available from: http://www.sage-ereference.com/view/research/n452.xml> . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peplau LA. Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindau ST, Garvilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US populations based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ. 2010;340:c810. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Refaie Shirpak KH, Eftekhar H, Mohammad K, Chinichian M, Ramezankhani A, Fotuhi A, Seraji M. Integration of sexual health education in health center services in Tehran. Payesh. 2007;6:243–56. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simbar M, Ramezani Tehrani F, Hashemi Z. Sexual-reproductive health belief model of college students. Iran South Med J. 2004;7:70–8. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashemi S, Seddigh S, Ramezani Tehrani F, Hasanzadeh Khansari SM, Khodakarami N. Sexual behavior of married Iranian women, attending Taleghani public health center. J Reprod Infertil. 2013;14:34–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziaee T, Khoury E. The point of view of employed married women about facilitating factors of sexual initiation. J Gorgan Bouyeh Faculty Nurs Midwifery. 2006;9:32–5. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Refaie Shirpak KH, Chinichian M, Eftekhar H, Pourreza A, Ramezankhani A. Need assessment: Sexual health education in family planning centers, Tehran, Iran. Payesh. 2010;9:251–60. Article in Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Impett EA, Peplau LA. Sexual compliance: Gender, motivational, and relationship perspectives. J Sex Res. 2003;40:87–100. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]