Abstract

Background:

Calendula officinalis (C. officinalis), commonly known as pot marigold, is a medicinal herb with excellent antimicrobial, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory activity.

Aim:

To evaluate the efficacy of C. officinalis in reducing dental plaque and gingival inflammation.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred and forty patients within the age group of 20-40 years were enrolled in this study with their informed consent. Patients having gingivitis (probing depth (PD) ≤3 mm), with a complaint of bleeding gums were included in this study. Patients with periodontitis PD ≥ 4 mm, desquamative gingivitis, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), smokers under antibiotic coverage, and any other history of systemic diseases or conditions, including pregnancy, were excluded from the study. The subjects were randomly assigned into two groups – test group (n = 120) and control group (n = 120). All the test group patients were advised to dilute 2 ml of tincture of calendula with 6 ml of distilled water and rinse their mouths once in the morning and once in the evening for six months. Similarly, the control group patients were advised to use 8 ml distilled water (placebo) as control mouthwash and rinse mouth twice daily for six months. Clinical parameters like the plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), sulcus bleeding index (SBI), and oral hygiene index-simplified (OHI-S) were recorded at baseline (first visit), third month (second visit), and sixth month (third visit) by the same operator, to rule out variable results. During the second visit, after recording the clinical parameters, each patient was subjected to undergo a thorough scaling procedure. Patients were instructed to carry out regular routine oral hygiene maintenance without any reinforcement in it.

Results:

In the absence of scaling (that is, between the first and second visit), the test group showed a statistically significant reduction in the scores of PI, GI, SBI (except OHI-S) (P < 0.05), whereas, the control group showed no reduction in scores when the baseline scores were compared with the third month scores. Also, when scaling was performed during the third month (second visit), there was statistically significant reduction in the scores of all parameters, when the third month scores were compared with the sixth month scores in both groups (P < 0.05), but the test group showed a significantly greater reduction in the PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S scores compared to those of the control group.

Conclusion:

Within the limits of this study, it can be concluded that calendula mouthwash is effective in reducing dental plaque and gingivitis adjunctive to scaling.

Keywords: Anti-gingivitis, anti-inflammatory, anti-plaque, Calendula officinalis

INTRODUCTION

Gingivitis is a chronic inflammatory process limited to the gingiva, without either attachment or alveolar bone loss. It is one of the most frequent oral diseases, affecting more than 90% of the population, regardless of age, sex or race. The earliest clinical sign is bleeding, which is a sequel of the vasodilator effect caused by an inflammatory response.[1] The prevention of gingivitis by daily and effective supragingival plaque control via brushing the teeth and dental floss is necessary to arrest a possible progression to periodontitis.[2,3]

Although mechanical plaque control methods have the potential to maintain adequate levels of oral hygiene, clinical experience and population-based studies have shown that such methods are not being employed accurately by a large number of people. Therefore, several chemotherapeutic agents such as triclosan, essential oils, and chlorhexidine have been developed to control bacterial plaque, aiming to improve the efficacy of daily oral hygiene control measures.[4]

The interest in plants with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity has increased as a consequence of the current problems associated with the wide-scale misuse of antibiotics that induce microbial drug resistance[5,6] and cytotoxic effects on the host cells.

Natural products such as Azadirachta indica, Aloe vera, Curcuma zedoaria, Punica granatum Linn., and other herbal products have been tested and are found to have effective medicinal properties. C. officinalis (family Asteraceae), mostly known as ‘pot marigold’, is a medicinal shrub native to the Mediterranean area, although, it is widely spread throughout the world. It produces yellow or orange flowers, which are used medicinally either in the form of infusion, tinctures, liquid extracts, creams or ointments. The plant contains polysaccharides, flavanoids, triterpene alcohols, phenol acids, tannins, glycosides, sterols, carotenoids, saponosides, and the like.[7]

Various researchers have shown C. officinalis to have antibacterial[8,9] and antifungal activity.[10] It also exhibits wound healing and re-epitheliazation,[11] anti-inflammatory,[12,13] antioxidant,[14] immunomodulatory[15,16] and anti-mutagenic[17,18] properties. It has reported no contraindications and no other drug interactions, but individuals with a known sensitivity to the Compositae family may be predisposed to allergic reactions.[19] Mouth rinsing with calendula will allow its anti-inflammatory properties to work against the swollen, irritated gums and its antibacterial properties deal with the periodontopathic microorganisms.[20] Calendula is also used for healing and soothing burns and sunburns, varicose ulcers, relieving sore throats, mouth ulcers, gastric upset, athlete's foot, ear infection, and so on.

AIM

Few studies have documented the effect of C. officinalis on gingival inflammation and gingival bleeding, but none of the studies has used a comparative control group. Hence, the present study was performed with the following aims:

To evaluate the efficacy of C. officinalis in reducing plaque and gingivitis

To compare C. officinalis with the control formulation, with or without adjunctive scaling to reduce gingivitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a randomized controlled trial study with a test group using the calendula mouthwash and a placebo control group. The study was carried out in the Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences University, India, between May 2009 and December 2010, under the approval of the Ethical Committee of the University.

Subjects

Two hundred and forty patients (20 - 40 years) who visited the Department of Periodontics at the Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences University with chief complaints of bleeding gums were enrolled in this study. All the subjects had at least 28 teeth other than the third molars. All participants were informed about the nature of the study and those who were willing to participate, signed an informed consent form in compliance with the guidelines of the Health Council of the University.

Inclusion criteria

Gingivitis with bleeding on probing (PD ≤ 3 mm)

Habits of cleaning teeth once in morning with a flat-end, medium bristles toothbrush, and a dentifrice

Patients complying to continue with the prescribed mouthwash as per the study protocol.

Exclusion criteria

Periodontitis (PD ≥ 4 mm)

Systemic medical disorder

Under antibiotic coverage

Habit of smoking and chewing smokeless tobacco

Pregnant women.

Clinical design

Two hundred and forty patients were randomly assigned into two groups: Test group n = 120 and control group n = 120. The randomization was done randomly by a non-operator.

Mother tinctures of C. officinalis were obtained from the Alpha Home Pharmacy, Nasik. Each patient in the test group was supplied with seven to eight bottles of calendula mother tincture and a measuring cylinder. The test group patients were advised to dilute 2 ml of calendula tincture († Dr. Willmar Schwabe Germany Home Pharmacy Pvt. Ltd [Manufacturer])with 6 ml of water. This diluted (1: 3)[21] formulation was prescribed for mouth rinsing twice daily for six months.

The control group patients were given distilled water as a control mouthwash (placebo) and were advised to rinse their mouth with 8 ml of it twice daily for six months. They were also supplied a measuring cylinder. All participants were strictly instructed not to bring any additional reinforcement into their oral hygiene practice during the given study period. All patients were re-called to the clinics at the third month (second visit) and at the sixth month (third visit). Patients with spontaneous severe bleeding gums, requiring immediate treatment were not considered, and thus, excluded from the study.

Clinical assessment

Clinical parameters like Turesky-Gilmore modification of the Quigley-Hein plaque Index (PI),[22] gingival index (GI),[23] sulcus bleeding index (SBI),[24] and oral hygiene index – simplified (OHIS) were recorded at the baseline, third month, and sixth month by the same operator, to rule out individual variations in results. Also, after recording the clinical parameters at the third month (during second visit), every patient was subjected to undergo a thorough scaling procedure by a skillful operator.

The Turesky-Gilmore modification of the Quigley-Hein plaque index (PI) measures the levels of dental plaque harboring the tooth surface in the fluid-filled oral cavity. The gingival index (GI) was used to assess the severity of gingivitis, the sulcus bleeding index (SBI) was helpful in evaluating the bleeding tendency in gingivitis patients, and lastly the oral hygiene index-simplified (OHI-S) assessed the personal oral hygiene status of an individual.

The PI score was assessed on the labial/buccal and lingual/palatal surfaces of all the teeth other than the third molars after applying a two-tone disclosing agent. The GI and SBI scores were recorded on the mesiobuccal, buccal, distobuccal, and lingual aspects of all the teeth, except the third molars. The gingival tissues were inspected for the presence of bleeding, recorded 10 seconds after running the tip of a William probe along the gingival margin (0.5-mm penetration into the sulci). The OHI-S score was evaluated on six selected experimental teeth, to determine the oral hygiene status of each participant. The mean values of PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S were calculated for the test and control groups.

Statistical analysis

The student paired ‘t’ test was used to evaluate the comparison of mean values of the differences in all parameters from the baseline to the third month, from baseline to the sixth month, and from the third month to the sixth month, in the test and control groups.

RESULTS

All the patients had a complete follow-up of six months. The calendula mouthwash showed good patient compliance, with greater taste acceptance and with an experience of freshness and willingness to continue, without any noticeable adverse effect like abscess, ulcerations, allergic reactions or the like.

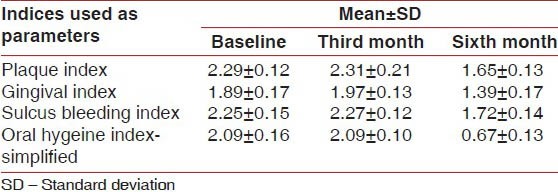

The mean values of all clinical parameters, with standard deviation, for the test and control groups at the baseline, third month, and sixth month are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of mean±SD values of various parameters at the baseline, third month, and sixth month in the calendula mouthwash test group (n=120)

Table 2.

Distribution of mean±SD values of all parameters at the baseline, third month, and sixth month in the control group (n=120)

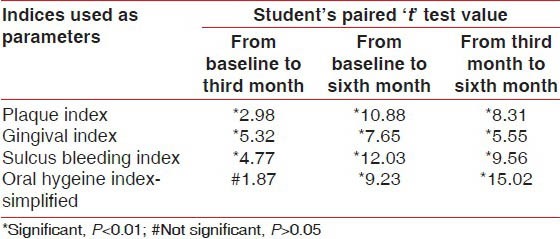

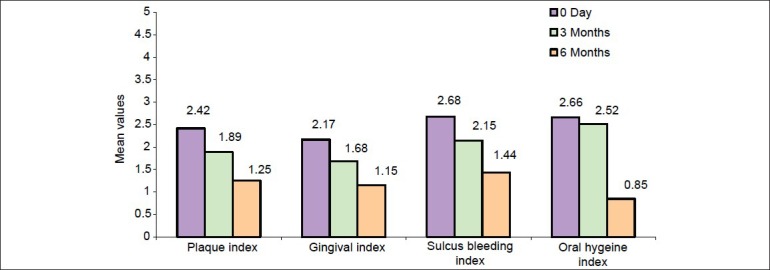

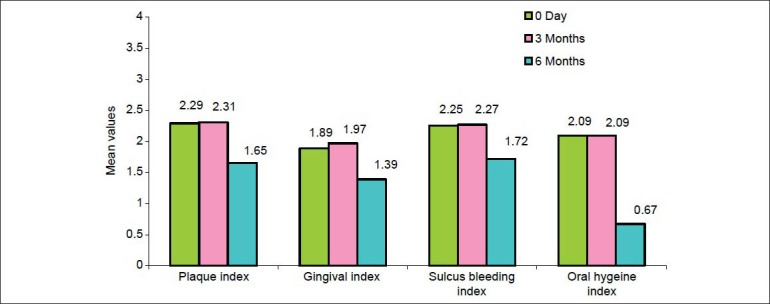

After applying Student's Paired ‘t’ test there was a highly significant difference in the mean values of PI, GI, and SBI, (except OHI-S, P < 0.01) when the baseline scores were compared with the third month scores. However, when the baseline scores were compared with the sixth month scores and similarly when the third month scores were compared with the sixth month scores, the result showed a statistically significant difference in PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S in the calendula test group. (i.e., P < 0.01) [Table 3]. The student paired ‘t’ test value showed that in the calendula test group there is a highly significant reduction in the mean values of PI, GI, and SBI scores from the baseline to the third month, from the third month to the sixth month, and from the baseline to the sixth month (P < 0.05), whereas, the OHIS score showed no significant reduction when the baseline score was compared with the third month score (P > 0.05), but showed a significant reduction when the third month score was compared with the sixth month score and when the baseline score was compared with the sixth month score (P < 0.05) [Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 3]. This significant reduction in the scores of PI, GI, and SBI from the baseline to the third month reflects the direct effect of calendula in reducing plaque and gingival bleeding in the absence of scaling; as also the reduction in score of all parameters from the third month to the sixth month reflects its effect as an adjunct to scaling. The significant reduction in the OHIS score from the third month to the sixth month is truly attributed to a thorough scaling done at the third month, after recording the clinical parameters [Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 3].

Table 3.

Value of student's paired ‘t’ test under comparison of mean values of all parameters from baseline to third month, from baseline to sixth month, and from third month to sixth month in the calendula test group (n=120)

Figure 1.

Bar diagram showing mean values of PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S at baseline, third month, and sixth month in test group

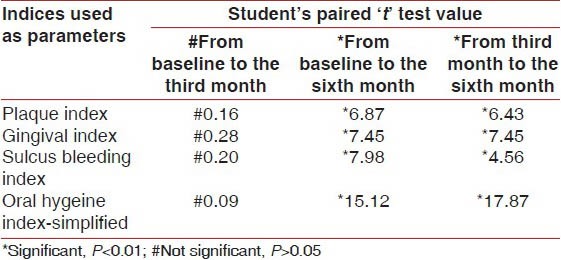

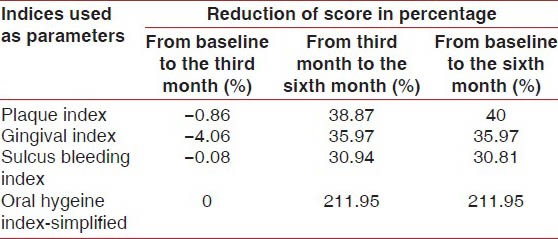

The student's paired test value showed that in the control group there was no significant decrease in the mean values of PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S when the baseline scores were compared with the third month scores (i.e., P > 0.05), however, there was a significant reduction in the mean values of all the parameters when the baseline scores were compared with the sixth month scores in the control group. Similarly, there was a significant reduction in the mean values of all the parameters when the third month scores were compared to the sixth month scores in the control group [Table 4]. The statistical result showed that in the control group there was no significant reduction in the mean value of the differences in the PI, GI, SBI, and OHIS scores from the baseline to the third month (P > 0.05), however, the mean values of PI, GI, SBI and OHIS showed significant reduction when the third month scores were compared with the sixth month scores (P < 0.05) and the baseline scores were compared with the sixth month scores (P < 0.05) [Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 4]. No significant reduction in the mean value of the scores of all parameters from the baseline to the third month signifies that placebo has no direct effect on the reduction of plaque and gingival inflammation in the absence of scaling. However, the significant reduction in mean values of all parameters from the third month to the sixth month was truly contributed to the thorough scaling performed on the third month visit [Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 4].

Table 4.

Values of student's paired ‘t’ test under comparison of differences of all parameters from baseline to the third month, from baseline to the sixth month, and from the third month to the sixth month in the placebo control group (n=120)

Figure 2.

Bar diagram showing mean values of PI, GI, SBI, and OHI-S at baseline, third month, and sixth month in control group

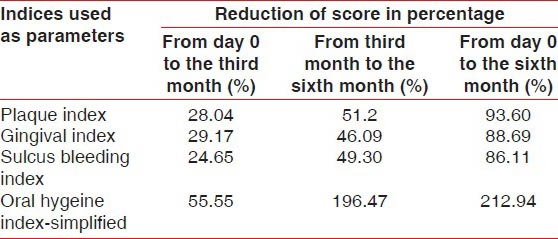

Also, when the percentage of reduction of scores from the third month to the sixth month of the calendula test group and control group were compared, the test group showed significantly greater reduction in scores than the control group, (Test group vs. control group from the third month to the sixth month), PI (51.2% vs. 38.87%), GI (46.09% vs. 35.97%), SBI (49.30% vs. 30.94%) [Tables 5 and 6].

Table 5.

Values showing reduction in the percentage of scores of all parameters from day 0 to the third month, from the third month to the sixth month and day 0 to the sixth month in the calendula test group (n=120)

Table 6.

Values showing reduction in percentage of scores of all parameters from baseline to the third month, from the third month to the sixth month, from baseline to the sixth month in the control group

DISCUSSION

Dental plaque is the main etiological agent of most forms of periodontal disease. To this day, mechanical methods of dental plaque removal are widely regarded as being effective means of helping to control progression of dental caries and periodontal diseases, which rank as one of the most common diseases in humans.[25]

However, for a variety of reasons, a mechanical routine does not appear to be sufficient for a majority of patients. Several chemotherapeutic agents are available commercially in the form of mouth rinses, which are known to have marked antiplaque and antigingivitis activity. Among them, the most commonly used mouth rinses are Chlorhexidine, Listerine, Povidone–Iodine, and Cetylpyridinium chloride. The antibacterial activity of these agents has been extensively studied and their efficacy proved. Unfortunately, the toxic qualities of these agents do not seem to be reserved only for bacteria, but also for fibroblasts,[26,27,28,29] macrophages,[30] PMNs,[31] epithelial cells, and erythrocytes.[32] However, Preethi et al.,[12] has demonstrated that calendula extract has no direct adverse effect on fibroblasts, but in fact, it can inhibit the cytotoxic effect on L929 fibroblast cells induced by LPS-stimulated macrophages. Also, Saini et al.,[33] has shown that calendula significantly inhibits human gingival fibroblast-mediated collagen degradation and MMP-2 activity. Lagarto et al., have demonstrated very low acute and subchronic oral toxicities of C. officinalis extract in Wistar rats.[34]

The result of our trial demonstrated that use of the C. officinalis mouthwash resulted in significantly greater reduction in plaque and gingivitis in comparison to the control placebo mouthwash. There is scarcity of material on the application of calendula as an anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis agent; the only study found was the one done by Yusoff et al., which reported that a calendula-containing mouthwash (plandula) was effective in reducing the PI score by 23.9% and the GI score by 62.3% during a 14-day study period.[35] Yusoff used plandula mouthwash, which contained Plantago, Fragaria, and Chamomilla, in addition to Calendula. However, in the present study, during the period of six months, pure Calendula diluted mother tincture was used as a mouthwash. PI was found to be reduced by 93.60%, GI by 88.69%, and SBI by 86.11%, in six months. The variation in results between the present study and that of Yusoff et al. may be due to the nature of the test mouthwash used, as also the study time period.

The calendula mouthwash group showed significant reduction in scores of PI (28.04%), GI (29.17%), and SBI (24.65%) from the baseline to the third month, that is, in the absence of scaling, whereas, the control group scores of PI, GI, and SBI were the same or slightly increased from the baseline to the third month [Tables 3 and 6]. This result reflected that calendula had some direct effect on reducing plaque and gingivitis, even in absence of scaling.

However, after scaling, from the third month to the sixth month, the calendula test group and the control group, both showed significant reduction in PI, GI, and SBI. However, the percentages in reduction of the score of PI, GI, and SBI were greater in the test group compared to the control group. This again signifies that calendula had a certain effect in reducing plaque and gingivitis when used as an adjunct to scaling.

Apart from its effect on plaque and gingivitis, the calendula extract also had an antimicrobial effect on periodontopathic microorganisms and an antifungal effect on many fungal infections. Iauk et al.,[22] demonstrated that the calendula flower extract possesses a high degree of anti-microbial activity against 18 different strains of anaerobic and facultative aerobic periodontal bacteria in vitro, suggesting that it may have an inhibitory effect on the bacteria causing pathogenesis of the supporting structures of the tooth. Zilda Cristaine et al.'s (2008), in vitro study, showed calendula to possess antifungal activity comparable to nystatin against different species of Candida including those causing oral candidiasis.[10]

Like chlorhexidine, calendula also has the property of substantivity as demonstrated by Schmidgall et al. in ex vivo laboratory model. Calendula has strong bio-adhesion to porcine buccal membrane, property is been attributed to polysaccharides and mucilage content in the herb.[36] Such effects suggest that it can be used for the therapeutic application in treatment of canker sore, apthous ulcer, sore throat, gingivitis, etc., However, comparative study of substantivity for chlorhexidine and calendula needs to be analyzed in future.

The aqueous extract of calendula facilitates wound healing by increasing neovascularization and rate of deposition of hyaluronic acid (GAGs). Also, the flavonoids in calendula are known to inhibit lysosomal hydrolase, which degrades the hyaluronic acid.[37] Hyaluronic acid is capable of accelerating new bone formation through mesenchymal cell differentiation in bone wounds.[38] Randomized controlled trials have shown reduction in radiation-induced oropharyngeal mucositis in patients with head and neck cancers.[39] Similar healing after oral application of gel containing calendula extract over oral mucositis, induced by chemical compound 5-fluorouracil, has been documented in Wistar rats.[40]

It has also been suggested that calendula accelerates wound healing through re-epitheliazation and collagen maturation.[11]

Calendula exerts anti-inflammatory activity through reducing the level of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL- 6, TNF- α, and INF-α in LPS-induced animals and also inhibits the expression of the Cox-2 gene.[12] Flavonoids and carotenoids are potent antioxidant components of calendula, which have free radical-scavenging activity against the OH-, NO-, DPPH+, and ABTS + radicals in a dose-dependent manner. Treatment with the extract of calendula enhanced the level of endogenous antioxidant catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione in animals.[14] The polysaccharide fraction of calendula has an immunomodulatory effect by stimulating the phagocytic activity of human granulocytes in vivo[10] and the phagocytic activity in mice.[11]

These anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties of calendula will be beneficial in the treatment of severe periodontitis by modulating the cytokines levels, reducing oxidative stress, and stimulating the phagocytic activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). More research, with the host modulatory effect of C. officinalis is warranted.

CONCLUSION

Within the limits of the study, it can be concluded that calendula mouthwash is effective in reducing dental plaque and gingivitis as an adjunct to oral prophylaxis. Various researches have documented that calendula possesses antimicrobial, wound healing, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-mutagenic activities. However, research data on the application of calendula to the treatment of moderate-to-severe periodontitis is limited. Hence, further multi-centered, long-term clinical trials are needed for further evaluation of C. officinalis – to prove its use as an anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis agent and also for its use in the treatment of severe periodontitis.

Limitation of study

The effect of using only distilled water as a placebo cannot be ruled out in reducing plaque and gingivitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Hemant Pawar for his kind support in the statistical analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amato R, Caton J, Polson A, Espeland M. Interproximal gingival inflammation related to conversion of bleeding to non–bleeding state. J Periodontal. 1986;57:63–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.2.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakdash B. Current patterns of oral hygiene product use and practices. Periodontal 2000. 1995;8:11–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SE. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Paola LG. Chemotherapeutic inhibition of supragingival dental plaque and gingivitis development. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:428–42. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pannuti CS, Grinbaum RS. An overview of nosocomial infection control in Brazil. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:170–4. doi: 10.1086/647080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.E.S.C.O.P. (Ed) Monographs (Monographs on Medicinal Uses Of Plants Drug) Exeter (Uk) 1997 V 01-12/06. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborthy GS. Antimicrobial activity of leaf extract of Calendula officinalis Linn. J Herb Med Toxicol. 2008;2:65–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumenil G, Chemli R, Balasaurd G. Evaluation of antibacterial properties of Calendula officinalis flowers and mother homeopathic tincture of calendula. Ann Pharm Fran. 1980;38:493–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zilda CG, Claudia MR, Sandra RF. Antifungal activity of the essential oil from Calendula officinalis L growing in Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2008;39:61–3. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220080001000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SG, Udupa AL, Udupa SL. Calendula and hypericum: Two homeopathic drug promoting wound healing in rats. Fitoteraperia. 1991;62:508–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preethi CG, Kuttan G, Kuttan R. Anti-inflammatory activity of flower extract of Calendula officinalis. Linn and its possible mechanism of action. Indian J Exp Biol. 2009;47:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Della Loggia R, Tubaro A, Sosa S, Becker H, Saar S, Isaac O. The role of titerpenoids in topical anti-inflammatory activity of Calendula officinalis flowers. Planta Med. 1994;60:516–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preethi KC, Utta GK. Antioxidant potential of an extract of Calendula officinalis in vitro and in vivo. Pharm Biol. 2006;44:691–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varljen J, Liptak A, Wagner H. Structural analysis of Rhamno-arabinogalactan and Arabinogalactans with immunostimulating activity from Calendula officinalis. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2379–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner H, Proksch A, Riess-Maurer I, Vollmar A, Odenthal S, Stuppner H, et al. Immunostimulating action of polysaccharides (heteroglycans) from higher plants. Arzneimittel for chung. 1985;7:1069–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elias R, De Méo M, Vidal-Ollivier E, Laget M, Balansard G, Dumenil G. Antimutgenic activity of some saponins isolated from Calendula officinalis L, arvensis L, hedera helix L. Mutagenesis. 1990;5:327–31. doi: 10.1093/mutage/5.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boucaud-Maitre Y, Algernon O, Raynaud J. Cytotoxic and anti tumoural activity of Calendula officinalis extracts. Pharmazie. 1988;43:220–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harkness R, Bratman S. 1st ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003. Mosby, s Handbook of drug-herb and drug-supplement interaction; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iauk L, Lo Bue AM, Millazoa I, Rapisarda A, BLandino G. Antibacterial activity of medicinal extracts against periodontopathic bacteria. Phytother Res. 2003;17:599–604. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krazhan IA, Garazha NN. Treatment of chronic catarrhal gingivitis with polysorb- immobilized calendula. Stomatologiia (Mosk) 2001;80:11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by chloromethyl analogue of vitamin C. J Periodontal. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy-prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival bleeding - a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Effect of controlled oral hygiene procedure on caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 6 years. J Clin Periodontal. 1981;8:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1981.tb02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flemingson, E mmadi P, Ambalavanan N, Ramakrishnan T, Vijayalakshmi R. Effect of three co mmercial mouth rinses on cultured human gingival fibroblast: An in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:26–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariotti AJ, Rump DA. Chlorhexidine-induced changes to human gingival fibroblast collagen and non-collagen protein production. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1443–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.12.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alleyn CD, O’Ne al RB, Strong SL, Scheidt MJ, Van Dyke TE, McPherson JC. The effect of chlorhexidine treatment of root surfaces on the attachment of human gingival fibroblast in vitro. J Periodontol. 1991;62:434–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.7.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cline NV, Layman DL. The effects of chlorhexidine on the attachment and growth of cultured human periodontal cells. J Periodontol. 1992;63:598–602. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.7.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knuutttila M, Soederling E. Effect of Chlorhexidine on the release of lysosomal enzymes from cultured macrophages. Acta Odontol Scand. 1981;39:285–9. doi: 10.3109/00016358109162291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenny EB, Saxe SR, Bowles RD. Effect of chlorhexidine on human polymorphonucear leucocytes. Arch Oral Biol. 1972;17:1633–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(72)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helgeland K, Heydan G, Rolla G. Effect of chlorhexidine on animal cell in vitro. Scand J Dent Res. 1971;79:209–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saini P, Al-Shibani N, Sun J, Zhang W, Song F, Gregson KS, et al. Effects of Calendula officinalis on human gingival fibroblasts. Homeopathy. 2012;101:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagarto A, Bueno V, Guerra I, Valdés O, Vega Y, Torres L. Acute and subchronic oral toxicities of Calendula officinalis extract in Wistar rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2011;63:387–91. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yusoff S, Kamin S. The effect of a mouthwash containing extract of Calendula officinalis on plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontal. 2006;33:118. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidgall J, Schnetz E, Hensel A. Evidence for bioadhesive effects of polysaccharides and polysaccharide-containing herbs in an ex vivo bioadhesion assay on buccal membranes. Planta Med. 2000;66:48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-11118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patrick K, Kumar S, Edwardson P, Hutchinnson J. Induction of vascularisation by aqueous extract of Calendula officinalis Linn. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:11–8. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki T, Watanabe C. Osteoinductive effect of hyaluronan. Bone. 1995;16:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(94)00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babaee N, Moslemi D, Khalilpour M, Vejdani F, Moghadamnia Y, Bijani A, et al. Antioxidant capacity of Calendula officinalis flowers extract and prevention of radiation induced oropharyngeal mucositis in patients with head and neck cancers: A randomized controlled clinical study. Daru. 2013;21:18–24. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanideh N, Tavakoli P, Saghiri MA, Garcia-Godoy F, Amanat D, Tadbir AA, et al. Healing acceleration in hamsters of oral mucositis induced by 5-fluorouracil with topical Calendula officinalis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.08.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]