Abstract

Background:

Pathologic migration is defined as change in tooth position resulting from disruption of the forces that maintain teeth in normal position in relation to their arch. The disruption of equilibrium in tooth position may be caused by several etiologic factors. So, the aim of the study was to evaluate the pathologic tooth migration (PTM) in the upper anterior sextant and its relationship with predisposing and external factors such as bone loss, tooth loss, gingival inflammation, age, parafunctions, lingual interposition in the tongue thrust, and oral habits.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the PTM in the upper anterior sextant and its relationship with predisposing and external factors such as bone loss, tooth loss, gingival inflammation, age, parafunctions, lingual interposition in the tongue thrust, and oral habits.

Materials and Methods:

The study sample consisted of 100 subjects of both sexes, with age ranging from 19 to 72 years. The probing pocket depth and gingival index were recorded for each patient. Competency of lips was also evaluated as competent or incompetent. Habits such as tongue thrusting, nail biting, and lip sucking were evaluated in relation to pathological migration of the tooth.

Results:

The results showed that no single factor by itself is clearly associated with PTM. As bone loss increases, the association of PTM with additional factors such as tooth loss and gingival inflammation increases.

Conclusion:

Further studies would be of great help to identify under which circumstances PTM is reversible according to the influence of gingival inflammation, malocclusion, and other factors. This information would contribute to a better understanding of some biological implications of the so-called minor tooth movement.

Keywords: Bone loss, inflammation, migration

INTRODUCTION

There is an ever increasing concern for dentofacial esthetics in adult population. Pathologic migration of anterior teeth is a common cause of esthetic concern among adults.[1]

Pathologic migration is defined as change in tooth position resulting from disruption of the forces that maintain teeth in normal position in relation to their arch.

The disruption of equilibrium in tooth position may be caused by several etiologic factors. These include periodontal attachment loss, pressure from inflamed tissues, occlusal factors, oral habits such as tongue thrusting and bruxism, loss of teeth without replacement, gingival enlargement, and iatrogenic factors.

However, according to the literature, destruction of tooth-supporting structures is the most relevant factor associated with pathologic migration. Periodontal disease in the upper anterior region can be in isolation or may affect more teeth. The periodontal disease and its sequel such as diastema, pathological migration, labial tipping, or missing teeth often lead to functional and esthetic problems, either alone or with restorative problems.[2] Advanced periodontal disease is characterized by severe attachment loss, reduced alveolar bone support, tooth mobility, and gingival recession.

Periodontal disease destruction of the attachment apparatus plays a major role in the etiology of pathological migration, producing esthetic and functional problems for the patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study sample consisted of 100 subjects of both sexes, with age ranging from 19 to 72 years, who were randomly selected from the patients attending the clinics of Department of Periodontics and Implantology. All the participants were informed about the study and they signed an informed consent form for participation in the study. The probing pocket depth (PPD) and gingival index (GI) were recorded for each patient. Competency of lips was also evaluated as competent or incompetent. Habits such as tongue thrusting, nail biting, and lip sucking were evaluated in relation to pathological migration of the tooth.

Clinical assessment

The clinical parameters evaluated were as follows:

PPD was measured with William's graduated periodontal probe

Gingival inflammation was determined according to a mean GI (Loe and Silness 1963)

Parafunctions such as bruxism and clenching were identified upon an interview and occlusal examination

The lingual interposition characteristic of tongue thrust was determined through examination of the swallow pattern

The presence of oral habits such as biting and holding objects between the teeth was determined upon an interview.

Radiographic assessment

Radiographic assessment of the teeth affected with pathologic migration was done by taking an Intraoral Periapical Radiograph (IOPA) with grid.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and Pearson correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

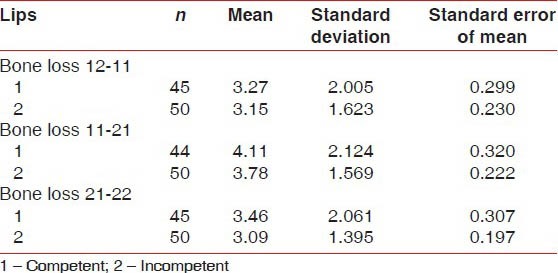

Table 1 shows the correlation of bone loss in PTM in the upper anterior sextant and the mean value for the age. No significant relation was found between bone loss and age, except for the region of 11-21, which was statistically significant (0.039). Group statistics and comparisons of bone loss between and within group has been discussed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Correlation between age and bone loss

Table 2.

Group statistics

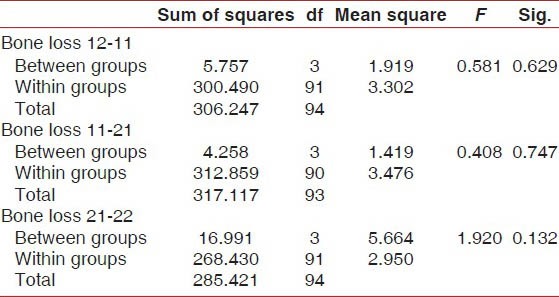

Table 3.

Comparison of bone loss between and within groups ANOVA

The prevalence of PTM increased with the severity of periodontal disease, as expressed by bone loss. No association was found between competency of lips and pathological migration.

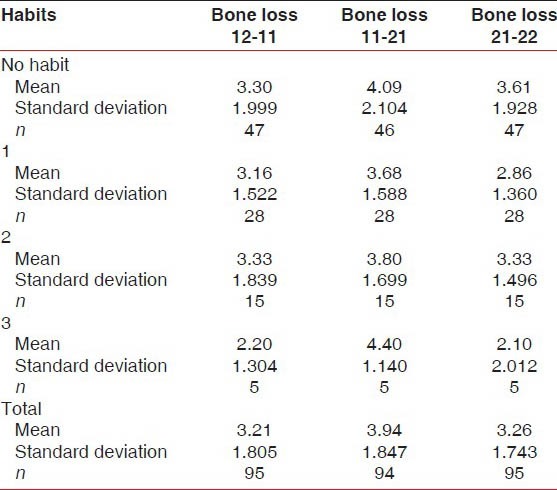

Habits

Weak association was found between oral habits and bone loss. Tongue thrusting, lip sucking, and nail biting habits showed no significant relation with bone loss in 11-12, 11-21, and 21-22 [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison between habits and bone loss

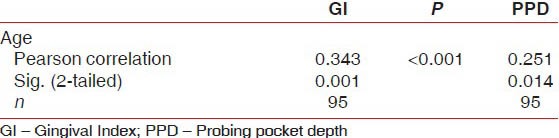

Gingival index

Table 5 shows the correlation between GI, PPD, and age. Statistically significant differences were found between GI and age (0.001).

Table 5.

Correlation between age with GI and PPD

Probing pocket depth

Table 3 shows the correlation between GI, PPD, and age. Statistically significant differences were found between PPD and age (0.014).

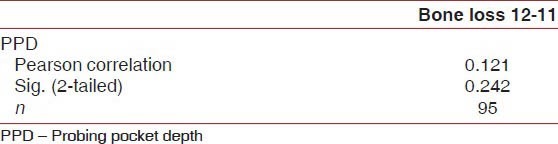

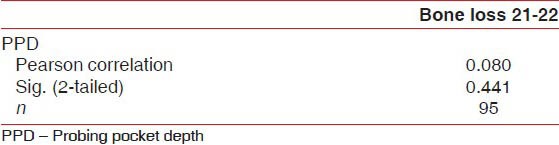

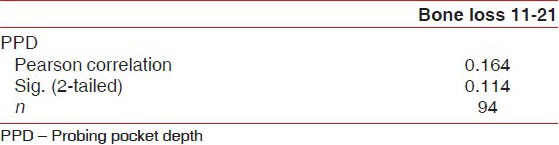

Combined effect of bone loss and probing pocket depth

Significant relation was found between bone loss in 11-21 and PPD (0.114). Bone loss in 21-22 with PPD (0.441) showed a positive correlation. Also, significant relation was found between bone loss in 12-11 and PPD (0.242) [Tables 6–8].

Table 6.

Comparison of bone loss with PPD

Table 8.

Comparison of bone loss with PPD

Table 7.

Comparison of bone loss with PPD

DISCUSSION

Within the limits of this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

No single factor by itself is clearly associated with PTM

The factor mainly related with PTM is bone loss, followed by PPD and gingival inflammation

As bone loss increases, the association of PTM with additional factors such as tooth loss and gingival inflammation increases.

Despite the fact that parafunctions such as bruxism and clenching have been related to PTM[3,4] and to occlusal attrition,[5] no association with PTM was found. However, while bruxism was easily detected by both the interview with the patient and the attrition pattern, clenching was more difficult to identify, so the results regarding this last association should be interpreted with caution. The presence of oral habits such as nail biting or holding objects between the teeth did not show a strong association with PTM. However, we could identify several cases in which the PTM was clearly related to such habits. Our findings on the relevance of bone loss and gingival inflammation are consistent with the literature, which points out two basic mechanisms involved in PTM. The first one is the occlusal changes associated with non-replaced missing teeth.[3,4,5,6,7] In the second one, PTM results from the pressure exerted upon the teeth by the granulomatous tissue of the periodontal pocket.[3,5,8] Both mechanisms take place simultaneously in many instances and their effect may be potentiated as loss of periodontal support increases.

CONCLUSION

Further studies would be of great help to identify under which circumstances PTM is reversible according to the influence of gingival inflammation, malocclusion, and other factors. This information would contribute to a better understanding of some biological implications of the so-called minor tooth movement.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ngom PI, Diagne F, Benoist HM, Thiam F. Intraarch and interarch relationships of the anterior teeth and periodontal conditions. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:236–42. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0236:IAIROT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helm S, Petersen PE. Causal relation between malocclusion and periodontal health. Acta Odontol Scand. 1989;47:223–8. doi: 10.3109/00016358909007705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschfeld L, Geiger A. Etiologic factors of tooth malposition. In: Hirschfeld L, Geiger A, editors. Minor tooth movement in general practice. St. Louis, MO: The CV. Mosby Co; 1974. pp. 78–139. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks MH, Levitt HL. Etiology of adult tooth malposition. In: Marks MH, Corn H, editors. Atlas of adult orthodontics. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1989. pp. 57–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carranza FA., Jr . Occlusal Trauma. In: Carranza FA Jr, editor. Giickman's Clinical Periodontology. Philadelphia: WB. Saunders Co; 1990. pp. 284–306. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heckert L. Prerestorative therapy using a modified Hawley split. J Prosthetic Dent. 1980;43:26–30. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dersot JM, Giovanoli JL. Posterior bite collapse (1), Etiology and diagnosis. J Periodontol. 1989;8:187–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschfeid L. The dynamic relationship between pathologically migrating teeth and inflammatory tissue in periodontal pockets: A clinical study. J Periodontol. 1933;4:35–47. [Google Scholar]