Abstract

Background:

Periodontitis is a group of inflammatory diseases affecting the supporting tissues of the tooth. Both aggressive periodontitis (AP) and chronic periodontitis (CP) have a multifactorial etiology, with dental plaque as the initiating factor. However, the initiation and progression of periodontitis are influenced by other factors including microbiologic, social and behavioral and systemic and genetic factors. The prevalence of periodontal diseases varies in different regions of the world according to the definition of periodontitis and the study population, and there are indications that they may be more prevalent in developing than in developed countries.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among the adolescents of 15-18 years of age in Mangalore City. One thousand one hundred students aged 15-18 years were selected for the study from the schools and colleges in Mangalore City using a convenient sampling method. The prevalence of AP and CP were assessed in the study using a community periodontal index. Students who were diagnosed clinically and radiographically were subjected to microbiological examination to confirm AP.

Results:

A high prevalence of gingivitis and periodontitis was found in students belonging to the lower socioeconomic status group compared with the higher socioeconomic groups, which were associated with poor oral hygiene habits. The prevalence of AP was found to be 0.36% and that of CP was found to be 1.5%.

Conclusion:

Oral diseases have a significant impact on the social and psychological aspects of an individual's life. Exposure to risk factors, such as age, low socio-economic status, poor education, low dental care utilization, poor oral hygiene levels, smoking, psychosocial stress and genetic factors are significantly associated with an increased risk of periodontitis among adolescents. Although genetic factors play a major role in periodontitis, the treatment outcome will still be influenced by environmental and behavioral factors.

Keywords: Age, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, community periodontal index, gender, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal diseases are a group of lesions affecting the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth. Paleopathological studies have indicated that diseases of the gums and tooth loss are as old as humanity. Children and adolescents can have any form of periodontitis as described in the proceedings of the 1999[1] International Workshop of Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. Epidemiologic studies indicate that gingivitis of varying severity is nearly universal in children and adolescents. These studies also indicate that the prevalence of destructive forms of periodontal disease is lower in young individuals than in adults. Epidemiologic surveys in young individuals have been performed in many parts of the world and among individuals with a widely varied background. For the most part, these surveys indicated that loss of periodontal attachment and supporting bone is relatively uncommon in the young, but that the incidence increases in adolescents.

The frequency of periodontitis is measured in terms of prevalence, incidence and severity and the extent of the disease is measured by indices or scales that quantify levels of disease. The determinants of disease refer to factors that increase the risk of disease onset or that identify the population subgroup most likely to have the disease under consideration.[2] It is well known that microorganisms and immunological and genetic factors play a major role in the etiology of periodontal disease. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey affords the opportunity to investigate whether race/ethnicity, individual income, education and neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics are independently associated with periodontal diseases.[3] Currently, more emphasis has been directed toward the combined influence of lifestyle, education and levels of socioeconomic status instead of regular risk factors in dealing with chronic illness.

In the light of the above facts, the present study was designed to assess the prevalence of periodontitis among the adolescents aged 15-18 years in Mangalore city and to determine the possible association between periodontal disease and factors such as oral hygiene habits, gender and parent's socioeconomical status and educational background.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

According to the Mangalore City Corporation, the total number of urban population is 419,306. Sixteen percent of the total urban population belongs to the age group of 15-18 years. The total number of schools and colleges in the city are 94. The total number of registered students between the age group of 15 and 18 years in these schools and colleges are 27,163, of which 13,948 are male and 13,215 are female students. The sample size for the study was decided using the formula n=4pq/L2

Of the total number of 27,163 students, 1100 students were selected for the study using a convenient sampling method. The survey procedure was divided into two stages and the duration of the study was 8 months.

Stage 1: In the first stage of the survey, the required information of each student enrolled in the study was obtained via a questionnaire that included demographic characters such as age, gender and socioeconomic status using Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale[4] (2007).

Stage 2: In the second stage of the survey, the periodontal status was assessed using the community periodontal index (CPI).[5] Each student was examined on an ordinary chair under adequate natural light by a single examiner [Figures 1 and 2]. The gingival and periodontal status of each student was assessed using a CPI-C WHO periodontal probe [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Armamentarium used for the study

Figure 2.

Oral examination of the students during the survey

Figure 3.

Photograph showing a periodontal pocket depth of 9 mm in relation to the distal aspect of 46

The students who presented with clinical signs of aggressive periodontitis (AP) with deep periodontal pockets, loss of attachment and tooth loss in the central incisor and first molar region were subjected to radiographic and microbiological examinations at the A.J. Institute of Dental Sciences. An orthopentamogram was taken for students who were clinically diagnosed with AP to assess the pattern of bone loss. In each study subject (patient with clinically diagnosed AP case), the tooth with the deepest pocket was sampled. The site chosen for the plaque sampling was the first molar and the central incisors. The area was isolated and dried with a cotton roll. Supragingival plaque was removed with a sterile instrument and the pocket was then sampled for subgingival microflora with a sterile curette. The plaque samples were transferred to brain heart infusion agar media. A primary inoculum was made and streaked in four quadrants to facilitate rough quantification according to the Wadsworth Anaerobic Laboratory Manual.[6] The incubation of the plates was performed in a candle jar at 37°C. After 48 h of incubation, the plates were observed under low-power (×10) and high-power (×40) objectives of the binocular compound microscope. Translucent colonies with central star-shaped configuration were presumptively identified as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A. actinomycetemcomitans) [Figure 4]. The data obtained were entered into a Microsoft excel sheet. A statistical package SPSS version 11.5 was used to perform the analysis. Test of significance was performed using the Chi-square test for qualitative data and ANOVA (Fisher's test) and Student's unpaired “t” test was used for quantitative data.

Figure 4.

Colony of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans under a microscope (×10) showing translucent colonies with central star-shaped configuration

RESULTS

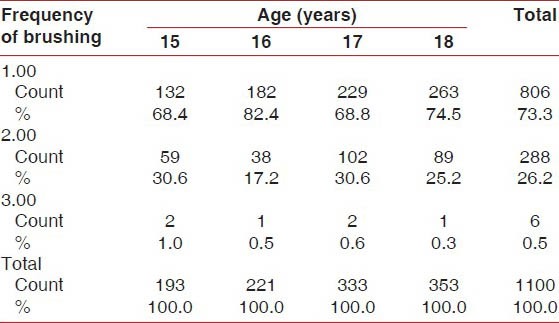

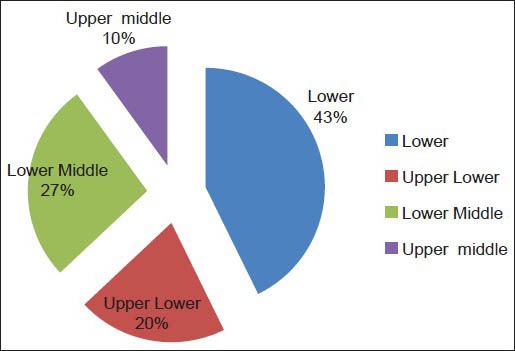

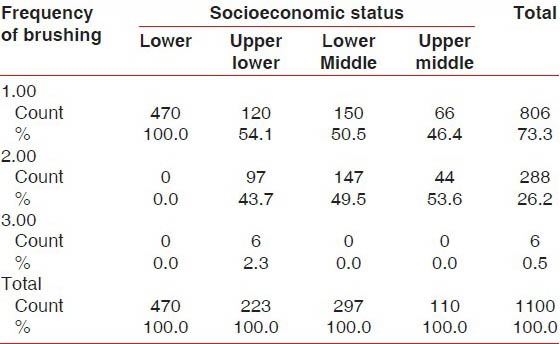

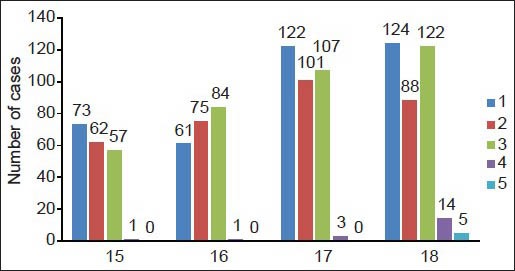

One thousand one hundred students were examined for the prevalence of gingivitis and periodontitis. Presence of gingivitis increased in the age group of 16 years, and these students brushed their teeth only once a day compared with students of the other age groups [Table 1]. Of the total 1100 students, 42.7% were from the low socioeconomic group [Graph 1]. This group of students brushed only once a day compared with the other socioeconomic groups [Table 2], which was one of factors for the development of gingivitis apart from increased levels of hormones at the time of puberty.

Table 1.

Percentage of frequencies of brushing versus age

Graph 1.

Pie diagram of various socioeconomic groups

Table 2.

Percentage of frequencies of brushing versus socioeconomic status

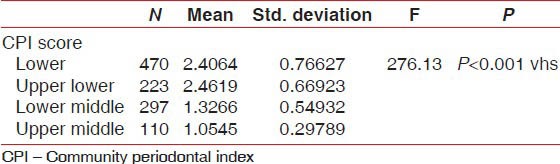

The highest CPI score was found in the lower socioeconomic status group compared with the other socioeconomic groups. A very high statistically significant association (P < 0.001) was observed between CPI score and socioeconomic status groups [Table 3].

Table 3.

Percentage of CPI scores versus socioeconomic status

Chronic periodontitis (CP) was diagnosed in 1.5% students of the subjects. Subjects with CP were significantly higher among the low socioeconomic group, with larger amounts of calculus. Subjects with CP had significantly higher percentages of sites with dental plaque, gingival bleeding and supragingival calculus than subjects without periodontitis. A periodontal pocket of 4-5 mm was seen in the 17 years age group (0.9%), followed by the 18 years age group (0.8%), 15 years age group (0.5%) and 16 years age group (0.5%). A periodontal pocket of 6 mm or more was seen only in the age group of 18 years (1.1%) [Graph 2]. These differences remained statistically significant after adjusting for the effects of age, race, gender, socioeconomic status, smoking and dental visits.

Graph 2.

Bar diagram of the percentage of CPI scores v/s age

Central incisors and molars were the most affected teeth with periodontal pockets. The percentage of subjects with AP was 0.36% [Graph 3]. Because both males and females were equally affected, there was no significance in gender and there was no significant difference of AP with the socioeconomic status of the students.

Graph 3.

Pie diagram of the percentage of aggressive periodontitis

DISCUSSION

This is the second study reporting the prevalence and risk indicators of AP in Mangalore city. An earlier study conducted in 1998[7] found a prevalence of 0.2% AP among the same study group, with a male to female ratio of 1:5.5. Our study showed a prevalence of 0.36% AP with a 1:1 male to female ratio. Studies regarding AP on Caucasians and Hispanics showed a greater female preponderance[8] whereas studies involving Blacks demonstrated a greater prevalence in males. Albandar et al.[9] reported a higher prevalence of AP among females than males in Saudi Arabia, with a male to female ratio of 1.9:1. In a study in southern Brazil, AP was distributed equally between males and females.[10] The reasons for these gender differences may be genetic factors, attitude toward oral health and dental-visit behavior.[11]

The school students represent adolescents who are likely a more periodontal-susceptible population. It has been demonstrated that gingivitis may develop into periodontitis with permanent destruction of the periodontal tissues from the age of about 15 years.[12] When these adolescents show levels of periodontitis as seen in Ramfjord et al.'s[13] surveys, it reflects poor dental service utilization by the population.

In our study, low level of education, income and occupation were significantly associated with the prevalence of gingivitis, and the odds of having periodontitis increased in subjects with a low socioeconomic background. A higher prevalence of periodontitis among subjects with low education has been reported in Thailand.[14] In the USA, Borrell et al. (2006)[15] reported that subjects with less than high school education were three-times more likely to have periodontitis than subjects with a higher level of education. Other studies in Nellore, India (2010),[16] and Dakshina Kannada, Karnataka, India (2010),[17] found a strong association of lifestyle, education and socioeconomic status on periodontal health.

The lowest prevalence of gingivitis was observed among subjects reporting regular tooth brushing and dental visits, whereas subjects reporting no tooth brushing had a higher odds of having periodontitis. The effect of maintaining good oral hygiene on the periodontium has been well documented.[18,19] Studies conducted in Wardha District, India (1989),[20] and among the Norwegian population (1990)[21] indicated the relationship between brushing behavior and oral health status. In accordance with these studies, our study demonstrated that students from the low socioeconomic group had a higher prevalence of gingivitis compared with the other groups.

Chronic gingivitis is the most common periodontal infection among children and adolescents. These may include plaque-induced chronic gingivitis (the most prevalent form), steroid hormone-related gingivitis, drug-influenced gingival overgrowth and others.[22,23,24] The initial clinical findings in gingivitis include redness and swelling of the marginal gingiva and bleeding upon probing. As the condition persists, tissues that were initially edematous may become more fibrotic. Probing depths may increase if significant hypertrophy or hyperplasia of the gingiva occurs. Although the microbiology of this disease has not been completely characterized, increased subgingival levels of Actinomyces species, Capnocytophaga species, Leptotrichia species and Selenomonas species have been found in experimental gingivitis in children when compared with gingivitis in adults. These species may therefore be important in its etiology and pathogenesis.[25,26]

In 1978,[27] a 21-day experimental gingivitis study found that children developed gingivitis less readily than adults. Also, children may have a different vascular response than adults. Studies conducted in 1996[28] found that older individuals formed similar amounts of plaque as the young subjects, but developed more gingivitis than young subjects. In our study, a higher prevalence of gingivitis was noticed among students of 15 years of age compared with the other age groups. An increase in the prevalence of gingivitis may be attributed to the increased levels of estrogen and progesterone during puberty, which resulted in increased gingival vascularity and inflammation.[29]

CP is the most prevalent in adults, but can occur in children and adolescents. Children and young adults with this form of disease were previously studied along with patients having localized aggressive periodontitis and generalized aggressive periodontitis. A study conducted in Brazil (2011)[30] found that adolescents and young adults had a high prevalence of CP and that its presence was associated with age, socioeconomic status and calculus. Our study showed a 1.5% prevalence of CP, and this may be associated with the socioeconomic status of the students.

It is well known that the etiology of periodontal diseases is bacterial plaque. However, patients affected by AP often present with impaired immune function, mainly neutrophil dysfunction. Therefore, it is important that when managing periodontal diseases in young individuals, the dentist should rule out systemic diseases that can affect host defense mechanisms. It is believed that the best approach to manage periodontal diseases is prevention, followed by early detection and treatment. To achieve this, profound knowledge about periodontics is essential.

It is important to reach out to the age group of students with preventive services, including oral hygiene education targeted toward parents and teachers. It is necessary to impart knowledge about daily oral hygiene practice and balanced nutrition supplements. This study only provides an insight of oral hygiene and periodontal status of a relatively small representation of the population and lacks to provide information on a larger population. It is, therefore, suggested to conduct studies on a larger scale to determine the prevalence of AP and CP among adolescents.

Although genetic factors play a major role in susceptibility to periodontitis, the search for the “Master Gene” responsible for periodontitis in an otherwise healthy individual has not been realized. Therefore, interpretation of the genotype status is not solely useful to alter the treatment regimen and the maintenance schedule.[30] Therefore, treatment outcome will still be heavily influenced by environmental and behavioral factors and whether an individual is genetically susceptible to disease or not.

To summarize, our study showed gingivitis and periodontitis among students of the low socioeconomic status. Lack of school-based preventive dental health programmes is a crucial health problem among this class of society. The high prevalence of gingival and periodontal disease and the lack of dental health services in schools are worrisome because, as a rapidly developing city, Mangalore has better health facilities compared with the other cities and rural areas in our country. Hence, an emphasis on further implementation of school-based oral health promotions and also an instigation of the preventive strategies is urgently needed in Mangalore city.

CONCLUSION

Oral diseases have been associated with mankind from time immemorial, but as they are rarely life-threatening, their prevention or treatment is often accorded a low priority by health policy makers. However, oral diseases can have a significant impact on both the social and the psychological aspects of an individual's life. Exposure to risk factors, such as age, low socio-economic status, poor education, low dental care utilization, poor oral hygiene level, smoking and psychosocial stress tend to concentrate in certain populations. Oral health problems are highly prevalent in the adolescents. Hence, attention should be focused on improving the oral health status of adolescents. Some suggestions and recommendations are as follows:

Educate and motivate students and their parents regarding the practice of good oral hygiene habits

Conduct oral health education and health promotion programmes, giving emphasis to personal counseling for those who belong to the lower socioeconomic group

To conduct more school dental health programmes

Conduct screening programmes regularly with the help of dental educational institutions, organizations like IDA and corporate sponsors

Provide quality dental care, free of cost, through primary health centers to the lower socioeconomic group

For the general welfare of the community, the government should take steps to fight the issues of poverty, unemployment and ill health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Academy report on Periodontal Diseases of Children and Adolescents. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1696–704. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.11.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locker D, Salde D. Epidemiology of Periodontal disease among older adults. A review. Periodontol 2000. 1998;16:16–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrell LN, Burt BA, Warren RC, Neighborsi HW. The role of individual and neighborhood social factors on periodontitis: The third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Periodontol. 2006;77:444–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar N, Shekhar C, Kumar P, Kundu AS. Kuppuswamy's Socioeconomic Status Scale updating for 2007. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:1131–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soben P. 2nd ed. Chapter 4 Essentials of Preventive and Community Dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutter VL, Citron DM, Edelstein MAC, Finegold SM. Wadsworth Anaerobic Bacteriology Manual. 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Star Publishing; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy PM, Jariwala U, Somayaji BV. Prevalence of juvenile periodontitis in Mangalore (India) J Indian Soc Periodontol. 1998;1:83–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baer PN. The case for periodontosis as a clinical entity. J Periodontol. 1971;42:516–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.8.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albandar JM. Periodontal disease in North America. Periodontology 2000. 2002;29:31–69. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Susin C, Albandar JM. Aggressive periodontitis in an urban population in southern Brazil. J Periodontol. 2005;76:468–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunn M. Understanding the etiology of periodontitis: An overview of periodontal risk factors. Periodontol 2000. 2003;32:11–23. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.03202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramfjord SP. Periodontal status of boys 11 to 17 years old in Bombay, India. J Periodontol. 1961;32:237–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramfjord SP, Emslie RD, Greene JC, Held AJ, Waerhaug J. Epidemiological studies of periodontal diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1968;58:1713–22. doi: 10.2105/ajph.58.9.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torrungruang K, Tamsailom S, Rojanasomsith K, Sutdhibhisal S, Nisapakultorn K, Vanichjakvong O, et al. Risk indicators of periodontal disease in older Thai adults. J Periodontol. 2005;76:558–65. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrell LN, Burt BA, Warren RC, Neighbors HW. The role of individual and neighborhood social factors on periodontitis: The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2006;77:444–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gundala R, Chava VK. Effect of lifestyle, education and socioeconomic status on periodontal health. Comtemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:23–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.62516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamath DG, Varma BR, Kamath SG, Kudpi RS. Comparision of periodontal status of urban and rural population in Dakshina Kannada District, Karnataka State. Oral Health Community Dent. 2010;4:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khader YS, Rice JC, Lefante JJ. Factors associated with periodontal diseases in a dental teaching clinic population in northern Jordan. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1610–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.11.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axelsson P, Nystrom B, Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 30 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:749–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao SP, Bharambe MS. Dental caries and periodontal diseases among urban, rural and tribal school children. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:759–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traeen B, Joostein R. Dental health behaviours in a Norwegian population. Community Dent Health. 1990;7:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell AL. The prevalence of periodontal disease in different populations during the circumpubertal period. J Periodontol. 1971;42:508–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.8.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blankenstein R, Murray JJ, Lind OP. Prevalence of chronic periodontitis in 13-15-year-old children. A radiographic study. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:285–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe MD, Carlos JP. Periodontal disease in adolescents: Epidemiologic findings in Navajo Indians. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore WE, Holdeman LV, Smibert RM, Cato EP, Burmeister JA, Palcanis KG, et al. Bacteriology of experimental gingivitis in children. Infect Immun. 1984;46:1–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.1-6.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slots J, Möenbo D, Langebaek J, Frandsen A. Microbiota of gingivitis in man. Scand J Dent. 1978;86:174–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1978.tb01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsson L. Development of gingivitis in preschool children and young adults. A comparative experimental study. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fransson C, Berglundh T, Lindhe J. The effect of age on the development of gingivitis. Clinical, microbiological and histological findings. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:379–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalkwarf KL. Effect of oral contraceptive therapy on gingival inflammation in humans. J Periodontol. 1978;49:560–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.11.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenstein G, Hart PC. Critical assessment of IL-1 genotypying when used in a genetic susceptibility test for severe chronic Periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2002;73:231–47. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]