SUMMARY

Regeneration capacity declines with age, but why juvenile organisms show enhanced tissue repair remains unexplained. Lin28a, a highly-conserved RNA binding protein expressed during embryogenesis, plays roles in development, pluripotency and metabolism. To determine if Lin28a might influence tissue repair in adults, we engineered the reactivation of Lin28a expression in several models of tissue injury. Lin28a reactivation improved hair regrowth by promoting anagen in hair follicles, and accelerated regrowth of cartilage, bone and mesenchyme after ear and digit injuries. Lin28a inhibits let-7 microRNA biogenesis; however let-7 repression was necessary but insufficient to enhance repair. Lin28a bound to and enhanced the translation of mRNAs for several metabolic enzymes, thereby increasing glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos). Lin28a-mediated enhancement of tissue repair was negated by OxPhos inhibition, whereas a pharmacologically-induced increase in OxPhos enhanced repair. Thus, Lin28a enhances tissue repair in some adult tissues by reprogramming cellular bioenergetics.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout the evolutionary spectrum of organisms, the juvenile state is associated with superior tissue repair (defined as the partial or complete restoration of cellular content and tissue integrity after injury). Drosophila and Tribolium larvae repair robustly, but the adult insects do not (Smith-Bolton et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2011). Tadpoles, but not adult frogs, can repair multiple tissues (Sánchez Alvarado and Tsonis, 2006), and in Ambystoma salamanders, regenerative capacity declines with age (Young et al., 1983). Young fish repair their caudal fins better than older ones (Anchelin et al., 2011), and it is well-known that during gestation, fetal mammals repair their tissues more robustly than older mammals (Deuchar, 1976; Conboy et al., 2005; Nishino et al., 2008; Porrello et al., 2011). In contrast, insects like the Apterygota, which do not undergo complete metamorphosis, retain remarkable larval capacities for appendage repair throughout life (Pearson, 1984), and some hyper-regenerative urodeles such as the neotenic Axolotl fail to undergo metamorphosis and exhibit larval regenerative potential throughout their lifespan. These exceptions notwithstanding, the correlation between juvenility and tissue repair has long been discussed by Charles Darwin and others (Darwin, 1887; Pearson, 1984; Poss, 2010), but the causal mechanisms remain obscure.

Lin28 is an RNA-binding protein first described in a C. elegans screen for heterochronic genes that regulate developmental timing. Loss of lin-28 causes precocious larval progression to adulthood, whereas gain of lin-28 delays larval progression and reiterates larval cell stages by promoting progenitor self-renewal (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Moss et al., 1997). Mammalian Lin28 exists as two highly-conserved paralogs, Lin28a and Lin28b, both of which repress let-7 microRNAs (Viswanathan et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2008; Heo et al., 2008; Rybak et al., 2008). In mammals, Lin28a is highly expressed in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and during embryogenesis, whereas mature let-7 rises as Lin28a levels wane during ESC differentiation, fetal development and aging (Shyh-Chang and Daley, 2013). Lin28a has also been used to reprogram human somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells (Yu et al., 2007) and in mice, Lin28a overexpression delays puberty and promotes growth (Zhu et al., 2010, 2011). Lin28b is also expressed in ESCs and extinguished in most tissues after birth, but it is not yet known if there are different physiologic roles or molecular targets for Lin28a and Lin28b. Conditional reactivation of Lin28a and LIN28B in adult mice prevents obesity and type 2 diabetes during aging, whereas conditional loss of Lin28a/b in fetuses causes dwarfism and promotes a diabetic state (Zhu et al., 2011; Shinoda et al., 2013). The human LIN28B gene shows polymorphisms strongly associated with puberty and height, indicating that the influence of Lin28 on development is evolutionarily conserved from worms to humans (Lettre et al., 2008; Widén et al., 2010; Ong et al., 2009; Sulem et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2011; Leinonen et al., 2012).

Prior studies linking Lin28 to juvenile programs of growth, development and metabolism led us to ask if reprogramming the developmental age of tissues with Lin28 could influence their post-natal repair capacities. Here we report that engineering the re-expression of Lin28a can enhance tissue repair in several contexts. Surprisingly, let-7 repression is necessary but alone insufficient to account for Lin28a’s enhancement of tissue repair. Lin28a also binds and increases the translation of the mRNAs for several metabolic enzymes including Pfkp, Pdha1, Idh3b, Sdha, Ndufb3 and Ndufb8 which, as established through metabolomic profiling, enhance oxidative metabolism to promote an embryonic bioenergetic state. Pharmacologic studies with inhibitors show that Lin28a-mediated tissue repair is more sensitive to OxPhos inhibition than is normal tissue repair. These data suggest that Lin28a promotes repair capacities in post-natal tissues by enhancing oxidative metabolism, both glycolysis and OxPhos, and promoting a bioenergetic state characteristic of embryonic cells.

RESULTS

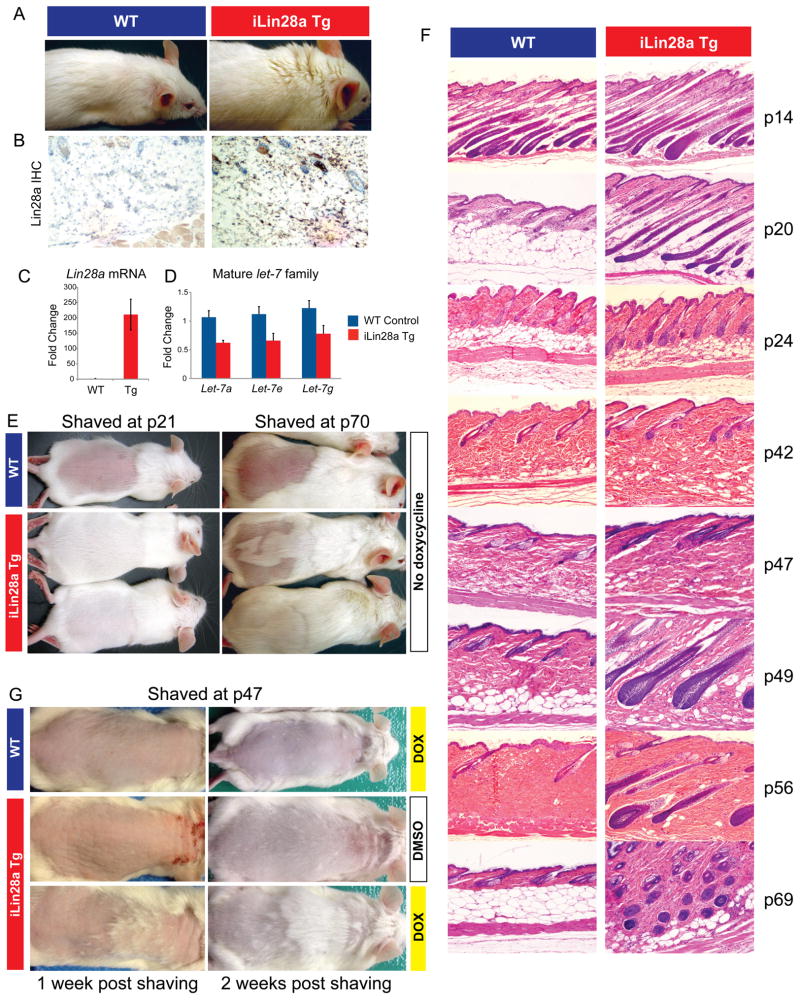

Lin28a promotes epidermal hair regrowth

Lin28a is expressed in the embryonic epidermis, but disappears by birth (Yang and Moss, 2003). We previously described a doxycycline (dox)-inducible Lin28a transgenic mouse (“iLin28a Tg”) with constitutive low levels of leaky Lin28a expression in the absence of induction (Zhu et al., 2010). Relative to non-transgenic wild type littermates (WT), iLin28a Tg mice displayed thicker hair coats and increased skin thickness (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A), correlating with Lin28a overexpression and let-7 repression in the epidermis (Fig. 1B–D). The hair appearance was not explained by greater hair follicle density or follicle bulb diameter (Fig. S1B,C). Given these observations, we asked if Lin28a overexpression might influence hair growth.

Figure 1. Lin28a reactivation promotes hair regrowth.

A. Uninduced iLin28a Tg mice possess a thicker fur coat than WT mice.

B. Lin28a expression in the skin of WT or iLin28a Tg mice as determined by immunohistochemistry.

C. Lin28a mRNA levels as determined by qRT-PCR.

D. Mature let-7 expression as determined by qRT-PCR in tail epidermis of WT and uninduced iLin28a Tg mice.

E. Hair regrowth in mice shaved at p21 was observed 1 week post-shaving in 0/6 WT vs. 6/6 Lin28a Tg littermates (Left image). Hair regrowth in mice shaved at p70 was observed 3 weeks post-shaving in 0/6 WT vs. 5/5 iLin28a Tg littermates (Right image).

F. Histologic hair cycle analysis over 10 weeks. All sections are 10x and H+E stained.

G. Hair regrowth on dorsal skin in topical dox-treated p47 WT and iLin28a Tg littermates, 1 and 2 weeks after shaving. Ectopic hair regrowth was observed in 0/4 WT dox treated vs. 0/3 DMSO treated Tg vs. 3/4 dox induced Tg mice. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01. See also Figure S1.

In mice, the hair follicle cycle is normally synchronized for the rst 10 weeks of life (Muller-Rover et al., 2001). The rst post-natal growth phase (anagen) ends at approximately post-natal day 16 (p16), followed by the rst resting phase (telogen). The second anagen begins at p28 and is followed by a second protracted telogen phase between p42 and p70 (Muller-Rover et al., 2001). We shaved the hair of mice expected to be in the first and second telogen phases (p21 and p70), and found that iLin28a Tg mice displayed enhanced dorsal hair regrowth at both of these time points (Fig. 1E). To explore the mechanism of this growth difference, we performed a full 10-week hair cycle survey and found that while WT mice conform to the expected timing of the anagen-telogen phases, iLin28a Tg mice have extended periods of anagen and shortened telogen (Fig. 1F). Specifically, WT mice were in telogen at p20, 24, 42, 47, 49, 56 and 69, while iLin28a Tg mice manifested only a brief resting phase at p42 and p47. We then asked if hair regrowth occurs differently in WT and iLin28a Tg mice when both are in anagen. We synchronized hair cycling using wax depilation, which removes the entire hair follicle and thus induces anagen in both genotypes, and found no differential in hair regrowth during anagen (Fig. S1D), which was corroborated by equivalent cell proliferation in anagen hair follicles (Fig. S1E). Additionally, we inquired if Lin28a induction could induce anagen during a telogen phase. We induced Lin28a by topical application of dox at p47, when both WT and iLin28a Tg mice were in telogen. Dox treated WT or DMSO treated iLin28a Tg mice showed no hair regrowth, whereas iLin28a Tg mice with topical dox showed patchy hair regrowth after 7 and 14 days, indicating that Lin28a overexpression during telogen is sufficient to induce anagen in hair follicles (Fig. 1G). Thus, Lin28a overexpression promotes hair regrowth by promoting anagen. Findings from this tissue context suggested that ectopic reactivation of Lin28a might be capable of promoting repair in other post-natal tissues as well.

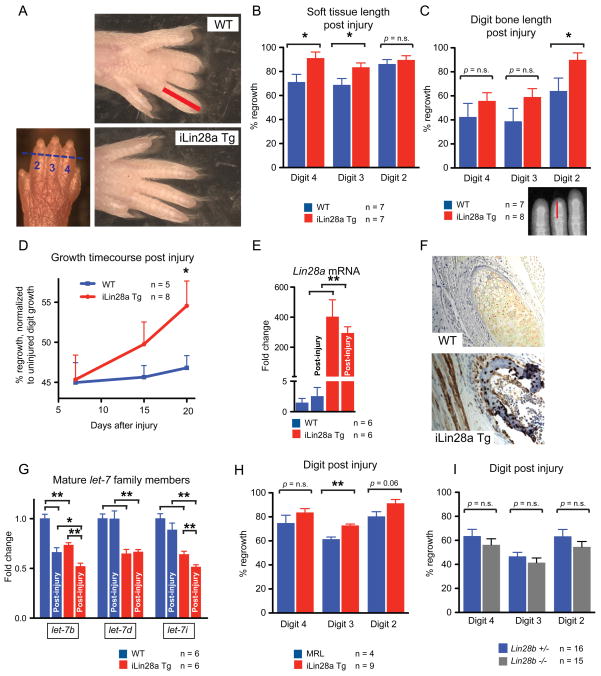

Lin28a promotes digit repair

Lin28a mRNA is expressed in the embryonic limb buds of E9.5 – E11.5 embryos, but declines sharply by birth (Yokoyama et al., 2008). Limb digits consist of multiple tissue types and show limited repair capacity after amputation in neonatal mammals. To assess their repair, mouse digits were amputated at the distal interphalangeal joint on day 2 after birth, and digit length was measured at 3 weeks of age. Relative to WT neonates, iLin28a Tg neonates displayed significantly enhanced connective tissue and bone regrowth in amputated digit tips (Fig. 2A–C). Even after normalizing for the greater body growth in iLin28a Tg mice, Lin28a accelerated the regrowth of injured digits over time (Fig. 2D). Whereas Lin28a showed no significant increase in expression in WT digits following amputation, Lin28a expression was elevated in iLin28a Tg digits before and after amputation (Fig. 2E–F). Consistent with this pattern, only let-7b dropped after digit amputation in WT mice, whereas several let-7 species were repressed both before and after injury in iLin28a Tg mice (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2. Lin28a reactivation promotes regrowth of digits after neonatal amputation.

For all digit measurements, % regrowth is quantified by dividing the length of the regrowing digit in the injured limb with the length of the normal digit on the opposite uninjured limb.

A. Left image shows p1 digits and the amputation site (blue hash mark). Right images show digits 21 days after neonatal digit amputation. Red bar depicts the soft tissue dimension measured between the digit tip and the proximal interphalangeal joint.

B. Quantification of soft tissue regrowth 21 days after neonatal digit amputation.

C. Quantification of bone regrowth 21 days after neonatal digit amputation. X-ray film with red bar showing that bone length was measured from the proximal interphalangeal joint.

D. Post-injury growth kinetics (as % of uninjured digit length) over 21 days.

E. Lin28a mRNA expression in WT, injured WT, iLin28a Tg, and injured iLin28a Tg digits, as determined by qRT-PCR.

F. Immunohistochemistry indicating Lin28a protein expression in Tg and WT bone from the neonatal skeleton.

G. Mature let-7 expression in WT, injured WT, iLin28a Tg, and injured iLin28a Tg digits, as determined by qRT-PCR.

H. Digit tip regrowth in iLin28a Tg mice backcrossed onto the hyper-regenerative MRL strain background. Control mice are WT MRL littermates. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01. See also Figure S2.

We next asked if Lin28a overexpression could further improve tissue repair in MRL mice, a well-known hyper-regenerative strain (Clark et al., 1998; Chadwick et al., 2007; Gourevitch et al., 2009). After backcrossing iLin28a Tg mice onto the MRL strain for 5 generations, Lin28a overexpression further enhanced digit tip repair relative to WT MRL controls, suggesting non-overlapping, additive mechanisms of enhanced repair. This supports the idea that even the repair capacity of the MRL strain could be augmented by genetic reactivation of Lin28a (Fig. 2H).

Because Lin28a improved neonatal digit repair, we hypothesized that Lin28a overexpression might also improve adult digit tip repair. In 5-week old mice, we amputated hindlimb digit tips, but found that reactivation of Lin28a expression conferred no significant enhancement of repair (Fig. S2), suggesting that Lin28a alone is insufficient to enhance adult repair in this context.

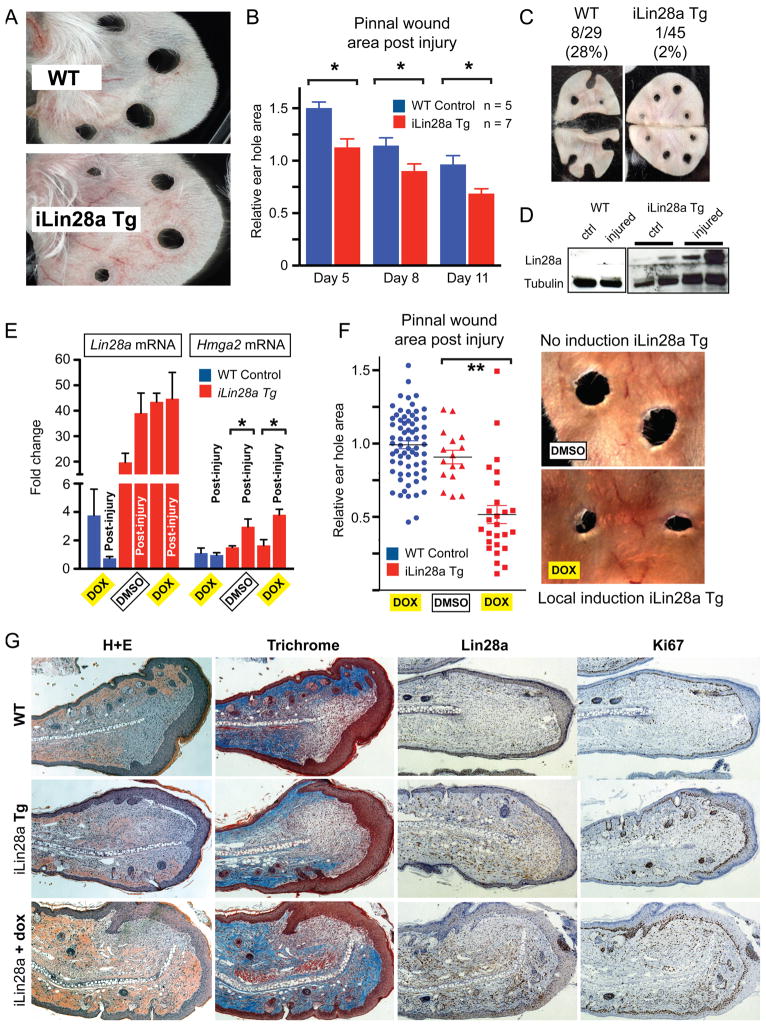

Lin28a promotes pinnal tissue repair

We assayed repair in the adult pinnal tissues of the outer ear, another complex tissue consisting of epidermis, cartilage and mesenchyme that fails to regenerate completely upon injury (Goss and Grimes, 1975; McBrearty et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2011). Low-level leaky Lin28a overexpression in the iLin28a Tg mice enhanced wound healing after 2mm full-thickness punch biopsy (Fig. 3A), as indicated by smaller wound sizes detected at 5, 8, and 11 days (Fig. 3B). In WT mice, 28% of the wounds could not be evaluated quantitatively because of poor healing and severe tearing of the wounds, whereas only 2% of wounds in iLin28a Tg mice displayed such severe damage (Fig. 3C). Similar to the digits, we observed a transient drop in let-7b following injury (Fig. 4A), but did not observe an increase in Lin28a during WT tissue repair (Fig. 3D, E). To determine if direct activation of Lin28a at the site of injury would promote pinnal repair, we applied dox topically onto wounds after punch biopsy. We detected local induction of Lin28a protein (Fig. 3D) and mRNA (Fig. 3E), and measured 50% greater wound closure after 11 days relative to uninduced iLin28a Tg ears (Fig. 3F). Hmga2, a prominent let-7 target, was also induced in iLin28a Tg but not in WT ears (Fig. 3E). Histologically, there was an increase in mesenchymal connective tissue after local Lin28a induction, and an increase in proliferation according to Ki67 staining (Fig. 3G), indicating that Lin28a induction promotes mesenchymal cell proliferation and tissue repair in pinnae. Interestingly, local dox induction of LIN28B in iLIN28B Tg mice (Zhu et al. 2011) was not sufficient to promote ear wound healing, suggesting a Lin28a-specific mechanism for this process (Fig. S3).

Figure 3. Lin28a reactivation promotes pinnal tissue repair.

A. WT and iLin28a Tg wound healing 8 days after 2mm-diameter ear hole punches.

B. Wound area size at day 5, 8, and 11, during the course of wound healing.

C. Proportion of WT and iLin28a Tg ear holes torn by mice after ear hole punching.

D. Western blot indicating Lin28a protein levels in topical dox-treated iLin28a Tg ears, before (n=2) and 3 days after (n=2) injury, compared to WT ears.

E. mRNA levels of Lin28a and the let-7 target Hmga2 in topical dox-treated iLin28a Tg ears, as determined by qRT-PCR.

F. Wound area size after 10 days of local topical treatment with dox.

G. H+E, trichrome, Lin28a, and Ki-67 staining in WT, iLin28a Tg and induced iLin28a Tg mice. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01. See also Figure S3.

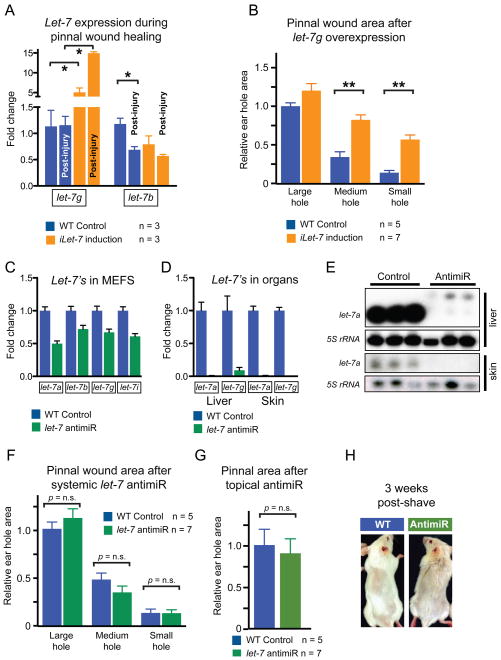

Figure 4. Let-7 repression is necessary but insufficient for tissue repair.

A. Expression of mature let-7g and let-7b in WT and iLet-7 ears, before and after injury, as determined by qRT-PCR.

B. Ear hole wound area size after whole animal let-7g induction in iLet-7 mice.

C. Mature let-7 miRNA expression in MEFs after let-7 antimiR treatment, as determined by qRT-PCR.

D. Mature let-7 miRNA expression in vivo after 2 subcutaneous injections of let-7 antimiR.

E. Northern blot indicating let-7a levels in the liver and skin of control and let-7 antimiR-treated WT mice.

F. Ear hole wound size after subcutaneous let-7 antimiR treatment of WT mice.

G. Ear hole wound size after local topical let-7 antimiR treatment of WT mice.

H. Hair regrowth after let-7 antimiR treatment of WT mice. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01.

Repression of let-7 is necessary but insufficient for promoting tissue repair

A major downstream effect of Lin28 is the repression of let-7 microRNAs. Because a subset of let-7 miRNAs decreased after digit and pinnal injury in WT animals (Fig. 2G, 4A), we hypothesized that repression of let-7 might be essential to tissue repair, and that enforced expression of let-7 would antagonize wound healing. We therefore assessed tissue repair in a transgenic mouse that expresses a dox-inducible form of the let-7 miRNA (“iLet-7 mice”; Zhu et al. 2011). Indeed, enforced overexpression of let-7 after ear punch biopsy inhibited wound closure and pinnal repair relative to uninduced mice, suggesting that let-7 repression is necessary for tissue repair (Fig. 4B). To test if let-7 repression would be sufficient to phenocopy the enhanced tissue repair observed with overexpression of Lin28a, we used a locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified antimiR to antagonize let-7 function. Previously, let-7 antimiRs successfully reduced mature let-7 levels and promoted an anti-diabetic phenotype in mice, thus phenocopying Lin28a overexpression (Frost and Olson 2011; Zhu et al. 2011). In our experiments, the let-7 antimiR repressed a wide range of mature let-7’s in MEFs and in vivo (Fig. 4C–E), to a greater extent than achieved by Lin28a overexpression. However, despite an efficient knockdown of let-7, neither systemic nor topical delivery of let-7 antimiR enhanced pinnal tissue repair (Fig. 4F,G) nor hair regrowth (Fig. 4H). These data indicate that let-7 antagonizes normal tissue repair, but also suggest that let-7 repression is necessary but not alone sufficient to explain the mechanism of enhanced tissue repair by Lin28a.

Lin28a alters the bioenergetic state during tissue repair

Lin28a/b and let-7 are known to regulate glucose metabolism, and transcripts encoding mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and glycolysis enzymes are among the top mRNAs bound by Lin28a (Peng et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011). To test the metabolic role of Lin28a in its most physiologically relevant context, we profiled metabolism in whole Lin28a−/− Lin28b−/− embryos vs. Lin28a+/+ Lin28b−/− embryos at E10.5 using Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry metabolomics (Shyh-Chang et al., 2013a). Lin28a deficiency led to lower levels of some glycolytic intermediates (Fig. S5A), lower ATP/AMP and NADH/NAD ratios, and higher levels of reduced glutathione (higher GSH/GSSG ratio, which indicates lower levels of reactive oxygen species or ROS; Fig. S5B). These data demonstrate that Lin28a is physiologically required for normal embryonic bioenergetics, and are consistent with our previous study that compared Lin28a+/− to Lin28a−/− embryos and likewise concluded that Lin28a is essential for normal embryonic metabolism (Shinoda et al., 2013).

These precedents prompted us to profile the metabolomic effects of Lin28a reactivation during tissue repair. We found that Lin28a induction led to an increase in several glycolytic intermediates in pinnal tissues after injury, suggesting a general increase in glucose oxidation, whereas WT ears exhibited few changes (Fig. 5A). Lin28a induction also enhanced the bioenergetic state during tissue repair in vivo, as indicated by the increase in acetyl-CoA, and the increased ATP/AMP and GTP/GMP bioenergetic ratios (Fig. 5B).

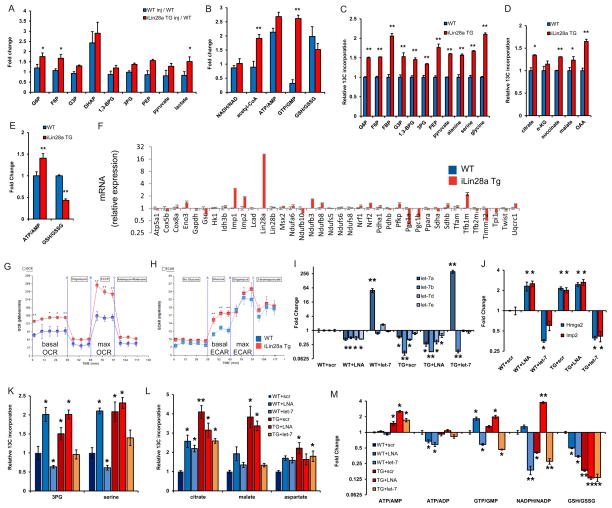

Figure 5. Lin28a alters the bioenergetic state during tissue repair.

A. LC-MS/MS selected reaction monitoring (SRM) analysis of abundance in glycolysis intermediates in WT and iLin28a Tg pinnal tissue after injury (inj), relative to WT uninjured pinnae. G3P, D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. DHAP, dihydroxyacetone-phosphate. BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate. 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate. PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

B. SRM analysis of several metabolic indicators in WT and iLin28a Tg pinnal tissue after injury (inj), relative to WT uninjured pinnae. ATP, adenosine-5′-triphosphate. AMP, adenosine-5′-monophosphate. GTP, guanosine-5′-triphosphate. GMP, guanosine-5′-monophosphate. GSH/GSSG, glutathione/glutathione disulfide.

C. Fraction of glycolytic intermediates labeled by 13C, derived from [U-13C]glucose in MEFs over 30 minutes, as measured by SRM analysis (n=3).

D. Fraction of Krebs cycle intermediates labeled at 2 carbons by 13C, derived from [U- 13 C]glucose in MEFs over 8 hours, as measured by SRM analysis (n=3).

E. SRM analysis of the ATP/AMP and GSH/GSSG ratios in WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs (n=3).

F. Mitochondrial biogenesis, glycolytic enzyme, and let-7 target mRNAs, analyzed by qRT-PCR. Lin28a, and the let-7 targets Imp1 and Imp2 served as positive controls. Relative expression levels were normalized to WT MEFs.

G. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, as measured by the Seahorse Analyzer (n=4 each). Oligomycin treatment inhibits ATP synthase-dependent OCR, the proton gradient uncoupler FCCP then induces maximal OCR, and antimycin/rotenone finally inhibits all OxPhos-dependent OCR.

H. Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, as measured by the Seahorse Analyzer (n=4 each). Addition of glucose induces glycolysis-dependent lactic acid production and ECAR, oligomycin then induces maximal ECAR, and 3BP partially inhibits glycolysis-dependent ECAR.

I. Mature let-7 expression in WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, after transfection with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex, as determined by qRT-PCR.

J. Expression of the let-7 targets Hmga2 and Imp2 in WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, after transfection with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex, as determined by qRT-PCR.

K. Fraction of the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) and the glycolytic side-product serine, labeled by 13C derived from [U-13C]glucose over 30 minutes, in MEFs after transfection with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex (n=3).

L. Fraction of the Krebs cycle intermediates citrate, malate and oxaloacetate-derived aspartate, labeled at 2 carbons by 13C derived from [U-13C]glucose over 8 hours, in MEFs after transfection with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex (n=3).

M. SRM analysis of several metabolic indicators in WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs after transfection with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex (n=3). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01. See also Figure S5.

Using 13C-glucose, we measured the flux of glucose through glycolysis and the Krebs cycle in MEFs, and found that Lin28a increased 13C-glucose flux into glycolysis (Fig. 5C), as well as the Krebs cycle (Fig. 5D), consistent with our observations in vivo. Furthermore, we found that the ATP/AMP ratio increased whereas the GSH/GSSG ratio decreased significantly with Lin28a overexpression (Fig. 5E), confirming that Lin28a enhances glucose oxidation to produce more ATP and ROS during tissue repair.

To determine if Lin28a was promoting the bioenergetic state by simply increasing mitochondrial biogenesis, we measured mitochondrial markers. We failed to detect increases in the mRNA levels of mitochondrial biogenesis markers and enzymes (Fig. 5F); there was no change in mitochondrial DNA (Fig. S5C); and CMXRos staining revealed no significant changes in the mitochondrial density and distribution (Fig. S5D). These data indicate that Lin28a enhances mitochondrial OxPhos activity rather than mass. We confirmed this using the Seahorse analyzer to measure the O2 consumption rates of primary MEFs from iLin28a Tg mice. Relative to WT control MEFs, Lin28a increased both the basal and maximal OxPhos capacity, as indicated by the increases in O2 consumption (Fig. 5G). Lin28a also increased the basal glycolytic capacity (Fig. 5H), consistent with findings from 13C-glucose flux studies.

To assess if Lin28a was causing metabolic changes in a let-7-dependent manner, we transfected a let-7 mimic and/or the let-7 antimiR into WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs. As expected, the let-7 LNA antimiR led to let-7 repression (Fig. 5I) and increased expression of the canonical let-7 targets Hmga2 and Imp2 (Fig. 5J), whereas the let-7 mimic led to the converse (Fig. 5I–J). 13C-glucose flux metabolomic profiling of these transfected MEFs then revealed that let-7 repression phenocopied Lin28a’s enhancement of glycolytic flux (into 3-phosphoglycerate and serine biosynthesis), whereas enforced let-7 overexpression suppressed WT glycolysis and partially abrogated Lin28a’s enhancement of glycolysis (Fig. 5K). However, let-7 repression failed to fully phenocopy Lin28a’s enhancement of Krebs cycle flux, and enforced let-7 overexpression failed to reduce WT Krebs cycle flux, although it did partially abrogate Lin28a’s enhancement of Krebs cycle flux (Fig. 5L). Most importantly, let-7 repression failed to phenocopy Lin28a’s enhancement of OxPhos, and enforced let-7 overexpression failed to block Lin28a’s enhancement of OxPhos (Fig. 5M). These results show that let-7 perturbation only partially phenocopies the metabolic effects of Lin28a, and support our conclusion that let-7 perturbation alone is necessary but insufficient to phenocopy Lin28a’s effects on tissue repair.

Lin28a promotes the expression of oxidative enzymes

Although Lin28a is well-known as a repressor of let-7 microRNA biogenesis, Lin28a also regulates mRNA translation independently of let-7 (Polesskaya et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2011; Wilbert et al., 2012; Cho et al., 2012). To show that Lin28a directly binds metabolic enzyme mRNAs in primary MEFs and pinnal tissues, we used RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) to show that FLAG-tagged Lin28a binds to mRNAs for Pfkp, Pdha1, Idh3b, Sdha, Ndufb3 and Ndufb8 (Fig. 6A,B). Furthermore, Lin28a overexpression resulted in increased protein levels of these metabolic genes, to varying degrees, in these settings (Fig. 6C), consistent with previous studies showing that Lin28a can directly enhance mRNA translation (Polesskaya et al., 2007). Interestingly, phosphofructokinase (Pfkp) and pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pdha1) are the rate-limiting enzymes that fuel glycolysis and the Krebs cycle respectively (Fig. S6A). Isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh3b) is the mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the first oxidative decarboxylation step in the Krebs cycle to produce α-ketoglutarate, NADH and CO2, whereas succinate dehydrogenase (Sdha) oxidizes succinate to produce fumarate and FADH2, and also serves as Complex II in the electron transport chain. NADH dehydrogenases (Ndufb3/8) constitute the rate-limiting Complex I in the electron transport chain that oxidizes NADH for ATP synthesis during OxPhos. Hence, Lin28a directly binds and increases translation of multiple rate-limiting enzyme components in both glycolysis and OxPhos (Fig. 6A–C).

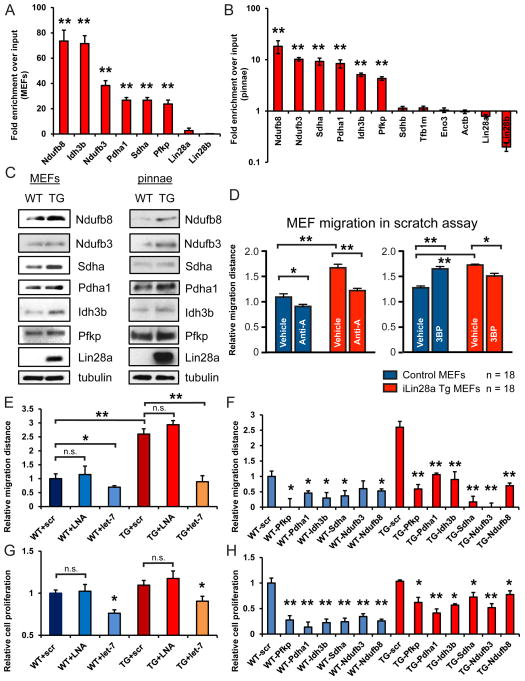

Figure 6. Lin28 promotes wound healing in vitro by enhancing bioenergetic metabolism.

A. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) using FLAG-tagged Lin28a and subsequent RT-PCR shows the metabolic enzyme mRNAs bound by Lin28a in MEFs in vitro.

B. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) using FLAG-tagged Lin28a and subsequent RT-PCR shows the metabolic enzyme mRNAs bound by Lin28a in pinnal tissues in vivo.

C. Western blots for Lin28a mRNA targets in primary MEFs and pinnal tissues in vivo,

D. Distance traveled by WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, 18 hours after a defined scratch was made on equal-numbered monolayers (n=18). MEFs were treated with 50nM Anti-A, 100uM 3BP, or DMSO vehicle control immediately after the scratch.

E. Distance traveled by WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs treated with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex.

F. Distance traveled by WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs treated with siRNAs against metabolic enzymes.

G. Cell proliferation of WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs treated with a scrambled (scr) control, let-7 LNA antimiR, or let-7a duplex.

H. Cell proliferation of WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs treated with siRNAs against metabolic enzymes. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01. See also Figure S6.

To determine if Lin28a-mediated metabolic enhancements might influence cell migration or proliferation, two processes that are critical for tissue repair (Guo and DiPietro, 2010), we subjected MEFs to in vitro migration and proliferation assays. Indeed, iLin28a Tg MEFs migrated more than WT MEFs (Fig. 6D). We then tested if pharmacological inhibition of glycolysis or OxPhos could influence MEF migration (see Fig. S6A for summary of inhibitor targets). OxPhos inhibition by antimycin-A, a specific electron transport chain Complex III inhibitor, reduced iLin28a Tg MEF migration more than WT MEFs (Fig. 6D). The glycolysis inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate (3BP) also reduced iLin28a Tg MEF migration more than WT MEFs (Fig. 6D), together suggesting that the enhanced cell migration associated with Lin28a expression is dependent upon enhanced glycolysis and OxPhos.

To determine if Lin28a influences cell migration in a let-7-dependent manner, we transfected the let-7 LNA antimiR and let-7 mimic into Tg and WT MEFs. Let-7 repression had no significant effects on WT or iLin28a Tg MEF migration, whereas enforced let-7 overexpression significantly inhibited both WT and iLin28a Tg MEF migration (Fig. 6E). These data are consistent with our observations that let-7 repression alone is necessary but insufficient to recapitulate Lin28a’s effects, suggesting that the mRNA targets of Lin28a play critical roles. Indeed, siRNA knockdown of individual enzyme subunits like Pfkp, Pdha1, Idh3b, Sdha, Ndufb3 or Ndufb8 (Fig. S6A–E) all impaired cell migration for WT and Tg MEFs (Fig. 6F), indicating that the stoichiometries of these enzyme complexes are critical to cell migration.

Cell proliferation is critical for tissue repair as well, but the importance of OxPhos for this process is unclear. OxPhos inhibition by antimycin-A impaired the proliferation of both WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs (Fig. S6F) with no changes in apoptosis, suggesting that normal OxPhos is essential for cell proliferation. Overexpression of let-7 inhibited cell proliferation in both WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs, whereas let-7 repression did not significantly affect proliferation in either (Fig. 6G). These data are consistent with our observations that let-7 repression is necessary but insufficient to recapitulate Lin28a’s effects, suggesting that the mRNA targets of Lin28a are critical. Depletion of Pfkp, Pdha1, Idh3b, Sdha, Ndufb3 or Ndufb8 (Fig. S6A–E), led to a defect in cell proliferation for both WT and iLin28a Tg MEFs (Fig. 6H), showing that the stoichiometries of these enzyme complexes – regulated by Lin28a – are important for cell proliferation.

Over the course of long-term passaging, Lin28a suppressed MEF proliferation in vitro (Fig. S6F) while in vivo, Lin28a promoted cell proliferation in hair follicles (Fig. 1) and pinnal tissues (Fig. 3G). Lin28a is therefore likely to be inducing senescence in vitro after passaging, through oxidative stress (Miyauchi et al., 2004; Nogueira et al., 2008; Kaplon et al., 2013). This counterintuitive effect is also observed when other oncogenes like Kras, Braf and PI3K are over-expressed in cells cultured in vitro, even when these oncogenes are known to promote cell proliferation in vivo.

To assess the importance of Lin28a-mediated metabolic changes in vivo, we applied specific pharmacologic inhibitors of glycolysis and OxPhos in the setting of hair regrowth (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 1, topical induction of Lin28a in the epidermis improves hair regrowth during telogen. OxPhos inhibition with topical antimycin-A (+dox) suppressed hair regrowth specifically in iLin28a Tg mice, with no effect on WT mice, indicating the effect was not due to overt tissue toxicity (Fig. 7A). Glycolysis inhibition with topical 3BP (+dox) also suppressed hair growth specifically in iLin28a Tg mice, without influencing WT mice. When the drugs were discontinued for 10 days, WT mice showed partial hair regrowth whereas iLin28a Tg mice showed complete regrowth, indicating that hair follicle cycling was only transiently, and not irreversibly inhibited by this dosing regimen (Fig. 7A). These results suggest that Lin28a promotes hair regrowth by enhancing glucose oxidation through both glycolysis and OxPhos.

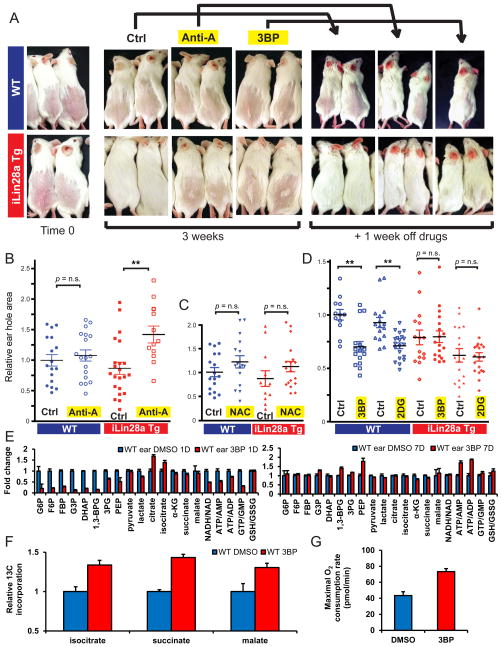

Figure 7. Lin28 promotes tissue repair in vivo by enhancing bioenergetic metabolism.

A. Hair regrowth of dorsal skin in p42 iLin28a Tg mice and WT littermates, at the time of shaving, and 3 weeks after local topical treatment with 3BP, or Anti-A, dissolved in 1g/L dox in DMSO (Ctrl). Mice were then taken off all treatment for 1 week.

B. Pinnal wound size after 10 days of local topical treatment with Anti-A, dissolved in 1g/L dox in DMSO (Ctrl), on both iLin28a Tg and WT littermate ear holes.

C. Pinnal wound size after 10 days of local topical treatment with the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) dissolved in 1g/L dox in DMSO (Ctrl), on both iLin28a Tg and WT littermate ear holes.

D. Pinnal wound size after 10 days of local topical treatment with the glycolysis inhibitors 3BP or 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) dissolved in 1g/L dox in DMSO (Ctrl), on both iLin28a Tg and WT littermate ear holes.

E. Metabolomic profiling on WT ears 1 and 7 days after daily 3BP treatment. Shown are glycolytic intermediates and the bioenergetics ratios NADH/NAD, ATP/AMP, ATP/ADP, and GTP/GMP (n=4).

F. Fraction of the Krebs cycle intermediates isocitrate, succinate, and malate, labeled at 2 carbons by 13C derived from [U-13C]glucose over 8 hours, in WT MEFs after continuous incubation in 3BP for 3 days (n=3).

G. Maximal O2 consumption rate in WT MEFs after continuous incubation in 3BP for 3 days (n=6). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM, * P<0.05, ** P< 0.01.

We sought to confirm this mechanism in another tissue context. Hence, we blocked OxPhos by topically applying antimycin-A daily on ears following pinnal injury. Consistent with the results in hair regrowth, antimycin-A abrogated Lin28a’s enhancement of pinnal repair, with no significant effects on WT pinnae (Fig. 7B). This suggests that iLin28a Tg tissue repair is more sensitive to OxPhos inhibition than WT tissue repair. In contrast, the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine had only a small effect on pinnal repair in both WT and iLin28a Tg mice (Fig. 7C), thus excluding a role for ROS or ROS-induced macrophage recruitment in the Lin28a mechanism.

Surprisingly, daily topical application of glycolysis inhibitors (3BP or 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2DG)), induced a substantial enhancement in WT tissue repair, comparable to the Lin28a-mediated enhancement (Fig. 7D). 3BP also enhanced migration in WT MEFs (Fig. 6D). One possible result of glycolysis inhibition is a compensatory increase in OxPhos activity, a phenomenon observed in cancer cells (Wu et al. 2007). To test if a compensatory increase in OxPhos explains why glycolysis inhibition in WT ears enhances tissue repair similarly to Lin28a overexpression (Fig. 7D), we performed metabolomic profiling on WT ears 1 and 7 days after daily 3BP treatment. 1 day after topical treatment, we found that 3BP drastically reduced glycolytic intermediates and decreased the NADH/NAD, ATP/AMP, ATP/ADP, and GTP/GMP bioenergetic ratios, as expected with glycolysis inhibition (Fig. 7E). After 7 days of daily 3BP treatment, however, the levels of glycolytic intermediates and the NADH/NAD ratio returned to normal, and there was a significant increase in the ATP/AMP and ATP/ADP ratios, indicating a compensatory increase in OxPhos activity in vivo (Fig. 7E). In WT MEFs, 3BP also led to an increase in 13C-glucose flux through the Krebs cycle (Fig. 7F), and an increase in the maximal O2 consumption rate (Fig. 7G), further confirming that chronic glycolysis inhibition by 3BP induces a compensatory increase in OxPhos to enhance tissue repair. Together with our results showing Lin28a’s enhancement of OxPhos (Fig. 5A–M), and the necessity for increased OxPhos in Lin28a’s enhancement of tissue repair in vivo (Fig. 7A–G), these results suggest that an enhancement of oxidative metabolism by Lin28a can confer the higher bioenergetic capacities needed to activate adult cells out of quiescence to enhance tissue repair.

DISCUSSION

Why some animals can fully regenerate organs when others cannot is a longstanding mystery of biology. Recent reports have shown that neonatal mice and select mouse strains have underappreciated regenerative capabilities, suggesting that some of the evolutionary ability to regenerate is retained in mammals but lost with development and age (Porrello et al., 2011; Clark et al., 1998). Most in vivo experiments have focused on loss of function screens in highly regenerative organisms like zebrafish and planaria. We have taken an alternative approach to this question by engineering improved tissue repair in mice, then discerning the underlying mechanisms.

Our work demonstrates that the highly conserved heterochronic gene and juvenility regulator Lin28a, first described in a genetic screen for C. elegans mutants with altered developmental timing (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984), promotes mammalian tissue repair by altering cellular metabolism. Lin28a is highly expressed in the early mammalian embryo, declines during mid-gestation, and silenced in most tissues after birth (Shyh-Chang and Daley, 2013). We have shown that engineering Lin28a reactivation in post-natal tissues reactivates an embryonic metabolic state that confers a reparative potential reminiscent of embryonic tissues. More generally, our studies support the concept that mammalian tissue repair can be substantially improved by engineering the reactivation of genes that regulate juvenile developmental stages. Importantly however, some tissues such as adult digits and the adult heart do not show improved tissue repair (Fig. S2, S7), illustrating that Lin28a’s influence is context dependent. In the zebrafish, lin-28 reactivation has also been found to promote retinal regeneration (Ramachandran et al., 2010).

It is surprising that Lin28a can promote tissue repair through mechanisms independent of let-7. Although overexpression of let-7 could inhibit tissue repair, let-7 repression alone failed to promote it. Though let-7 repression is necessary but insufficient to promote tissue repair, it is possible that let-7-dependent and independent functions of Lin28 synergize during tissue repair. There is ample evidence that Lin28a, like other RNA-binding proteins, regulates the translation of thousands of mRNAs and thus operates at the systems level (Peng et al., 2011; Wilbert et al., 2012; Cho et al., 2012). Future mechanistic and therapeutic investigation will focus on identifying additional targets of Lin28a that might also play a role in tissue repair.

Lin28a is emerging as a progenitor and stem cell factor that regulates metabolism to promote self-renewal (Shyh-Chang et al., 2013b), and here we demonstrate its effects in vivo. Since specific inhibition of OxPhos can negate Lin28a’s beneficial effects on tissue repair without detriment to WT tissue repair, Lin28a is promoting tissue repair at least in part by enhancing oxidative metabolism and bioenergetics. Mechanistically, enhanced ATP/AMP and GTP/GMP ratios could supply the higher energetic needs of anabolic biosynthesis, mitosis, and migration during tissue repair, or promote growth signaling pathways like mTOR, all of which are enhanced by Lin28a. It is interesting to note that prior studies have linked the PPARs (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors), master regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism, to tissue repair in the mammalian skin, liver, muscles, and cornea (Michalik et al., 2001; Anderson et al., 2002; Angione et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2012). ATP-powered ion gradients and ROS have also been found to be critical in other regenerative animal models, such as Xenopus tail and planarian regeneration (Adams et al., 2007; Beane et al., 2011; Love et al., 2013). Clinically, the utility of topical oxygen for chronic wound therapy (Schreml et al., 2010), might also be partially related to the metabolic mechanisms that we have identified for Lin28a. Our findings support the novel use for Lin28a and the enhancement of oxidative metabolism for treating injuries and diseases resulting from tissue damage and degeneration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

All animal procedures were based on animal care guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Digit amputation

Neonatal mice were cryoanesthetized before the forelimb and hindlimb central digits 2, 3, and 4 were amputated at the distal interphalangeal joint using a #11 scalpel under a dissection microscope. In all animals, right limb digits were left un-amputated as controls. Digit regrowth was measured as % of the uninjured digit length. In adults, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine before 400μm of hindlimb digits 2 and 4 were amputated using a #11 scalpel. Digit 3 was left unamputated as a control. X-ray imaging was performed using the MX-20 Specimen Radiograph System (Faxitron, Tucson, AZ).

Ear hole punch assay

A 2-mm-diameter hole (large) was punched in the center of each outer ear (pinna) by using a clinical biopsy punch (Roboz, Gaithersburg, MD). For profiling experiments, the entire pinna was punched throughout with 1-mm-diameter holes (small) to maximize the amount of pinnal tissue undergoing tissue repair.

Quantitative RT-PCR, Western blot and Immunohistochemistry

All assessments of mRNA levels were performed by qRT-PCR using commercial primers (OriGene), and all assessments of protein levels were performed by Western immunoblotting with anti-Lin28a, anti-tubulin (Cell Signaling), anti-Ndufb8, anti-Pdha1, anti-Pfkp, anti-Sdha, (Abcam), anti-Idh3b, or anti-Ndufb3 (Santa Cruz). For immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated with anti-Lin28a (Cell Signaling), anti-Lin28b (Cell Signaling), anti-Ki-67 (Dako), anti-phospho-H3 (Ser10) or anti-BrdU (Cell Signaling), and visualized using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC System (Vector Labs).

RNA immunoprecipitation

Cells and tissues were lysed in M2 buffer with RNAse inhibitor, then incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel beads (Sigma Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, to pull-down FLAG-tagged Lin28a. After 4 washes with M2 buffer, RNA bound to the M2 affinity gel beads was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen).

Metabolomics, and Seahorse Analyzer

Metabolomics analysis was performed as previously described (Shyh-Chang et al., 2013a). Seahorse data analysis was performed as previously described (Wu et al., 2007).

Drug treatments

For the pinnal repair experiments, 25uL of 5mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose, 100uM 3-bromopyruvate, 500nM antimycin-A, or 10mM N-acetyl-cysteine, was applied topically on each ear 3 times a week, with 1 g/L dox dissolved in DMSO as the vehicle control. LNA antimiRs (Exiqon, Denmark) were injected subcutaneously once weekly as previously described (Frost and Olson 2011), or applied topically with 25ug LNA per ear using jetPEI according to manufacturer instructions (Polyplus, France).

Histology

Tissue samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin or Bouin’s solution and embedded in paraffin.

Statistical analysis

Data is presented as mean ± SEM, and Student’s t-test (two-tailed distribution, two-sample unequal variance) was used to calculate p values. Statistical significance is displayed as p < 0.05 (one asterisk) or p < 0.01 (two asterisks) unless specified otherwise. The tests were performed using Microsoft Excel.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Lin28a reactivation promotes hair regrowth, as well as ear and digit tissue repair.

Excess let-7 inhibits tissue repair, but anti-let-7 therapy fails to promote tissue repair.

Lin28a promotes tissue repair by enhancing the translation of some oxidative enzymes.

Lin28a’s enhancement of tissue repair was negated by OxPhos inhibition.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Powers, Costas Lyssiotis, Charles Kaufman, Jessica Lehoczky, and Clifford Tabin for invaluable feedback and discussions, Jin Zhang and the lab of Marcia Haigis for help with the Seahorse Analyzer, Min Yuan and Susanne Breitkopf for help with metabolomics, Samar Shah and Akiko Yabuuchi for help with the mouse work, Asher Bomer for help with the scratch assays, James Thornton for help with Northern blots, Roderick Bronson and the Harvard Medical School Rodent Histopathology Core for mouse tissue pathology. This work was supported by an A*STAR National Science Scholarship to N.S.C., a Graduate Training in Cancer Research Grant, a American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, an NIH K08 grant and a CPRIT award to H.Z., a Herchel Smith Graduate Fellowship to K.M.T., and a grant from the Ellison Medical Foundation to G.Q.D. G.Q.D. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.S.C. and H.Z. designed and performed the experiments. N.S.C., H.Z., and G.Q.D. wrote the manuscript. G.S., T.Y.D., M.T.S., L.N., K.M.T. helped with various experiments and mouse husbandry. J.M.A. helped with metabolomics and L.C.C. supervised all metabolism experiments. G.Q.D. designed and supervised experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams DS, et al. H+ pump-dependent changes in membrane voltage are an early mechanism necessary and sufficient to induce Xenopus tail regeneration. Development. 2007;1335:1323–1335. doi: 10.1242/dev.02812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V, Horvitz H. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–416. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anchelin M, et al. Behaviour of telomere and telomerase during aging and regeneration in zebrafish. PloS One. 2011;6:e16955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SP, et al. Delayed liver regeneration in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α-null mice. Hepatology. 2002;36:544–54. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angione AR, et al. PPARδ regulates satellite cell proliferation and skeletal muscle regeneration. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:1–33. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beane WS, et al. A Chemical Genetics Approach Reveals H, K-ATPase-Mediated Membrane Voltage Is Required for Planarian Head Regeneration. Chem Biol. 2011;18:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick RB, et al. Digit tip regrowth and differential gene expression in MRL/Mpj, DBA/2, and C57BL/6 mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:275–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, et al. LIN28A Is a Suppressor of ER-Associated Translation in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2012;151:765–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LD, et al. A new murine model for mammalian wound repair and regeneration. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:35–45. doi: 10.1006/clin.1998.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, et al. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433:760–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. (Forgotten Books Classic Reprint Series) 1887 [Google Scholar]

- Deuchar BEM. Regeneration of amputated limb-buds in early rat embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1976;35:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RJA, Olson EN. Control of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by the Let-7 family of miRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss RJ, Grimes LN. Epidermal downgrowths in regenerating rabbit ear holes. J Morphol. 1975;146:533–42. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051460408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourevitch DL, et al. Dynamic changes after murine digit amputation: the MRL mouse digit shows waves of tissue remodeling, growth, and apoptosis. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:447–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, DiPietro LA. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo I, et al. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MiRNA. Mol Cell. 2008;32:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon J, et al. A key role for mitochondrial gatekeeper pyruvate dehydrogenase in oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2013;498:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen JT, et al. Association of LIN28B with Adult Adiposity-Related Traits in Females. PloS One. 2012;7:e48785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettre G, et al. Identification of ten loci associated with height highlights new biological pathways in human growth. Nat Genet. 2008;40:584–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, et al. Regenerative phenotype in mice with a point mutation in transforming growth factor β type I receptor (TGFBR1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14560–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111056108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love NR, et al. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:222–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalik L, et al. Impaired skin wound healing in peroxisome proliferator receptor (PPAR)α and PPARβ mutant mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:799–814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi H, et al. Akt negatively regulates the in vitro lifespan of human endothelial cells via a p53/p21-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 2004;23:212–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrearty BA, et al. Genetic analysis of a mammalian wound-healing trait. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11792–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EG, et al. The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell. 1997;88:637–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, et al. A Comprehensive Guide for the Accurate Classification of Murine Hair Follicles in Distinct Hair Cycle Stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, et al. Functional role of PPARδ in corneal epithelial wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:583–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M, et al. Lin-28 interaction with the Let-7 precursor loop mediates regulated miRNA processing. RNA. 2008;14:1539–49. doi: 10.1261/rna.1155108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino J, et al. Hmga2 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in young but not old mice by reducing p16Ink4a and p19Arf Expression. Cell. 2008;135:227–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira V, et al. Akt determines replicative senescence and oxidative or oncogenic premature senescence and sensitizes cells to oxidative apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:458–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KK, et al. Genetic variation in LIN28B is associated with the timing of puberty. Nat Genet. 2009;41:729–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KK, et al. Associations between the pubertal timing-related variant in LIN28B and BMI vary across the life course. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E125–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RD. Neotenic blastemal morphogenesis. Acta Biotheoretica. 1984;33:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, et al. Genome-wide Studies Reveal that Lin28 Enhances the Translation of Genes Important for Growth and Survival of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:496–504. doi: 10.1002/stem.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JRB, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies two loci influencing age at menarche. Nat Genet. 2009;41:648–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polesskaya A, et al. Lin-28 binds IGF-2 mRNA and participates in skeletal myogenesis by increasing translation efficiency. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1125–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.415007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrello ER, et al. Transient Regenerative Potential of the Neonatal Mouse Heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss KD. Advances in understanding tissue regenerative capacity and mechanisms in animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:710–721. doi: 10.1038/nrg2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, et al. Ascl1a regulates Muller glia dedifferentiation and retinal regeneration through a Lin-28-dependent, let-7 microRNA signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1101–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak A, et al. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Alvarado A, Tsonis PA. Bridging the regeneration gap: genetic insights from diverse animal models. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:873–84. doi: 10.1038/nrg1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreml S, et al. Oxygen in acute and chronic wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:257–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MV, et al. The role of canonical Wnt signaling in leg regeneration and metamorphosis in the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. Mech Dev. 2011;128:342–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda G, et al. Fetal deficiency of Lin28 programs life-long aberrations in growth and glucose metabolism. Stem Cells. 2013 doi: 10.1002/stem.1423. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyh-Chang N, et al. Influence of threonine metabolism on S-adenosylmethionine and histone methylation. Science. 2013a;339:222–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1226603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyh-Chang N, et al. Stem cell metabolism in tissue development and aging. Development. 2013b;140:2535–47. doi: 10.1242/dev.091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyh-Chang N, Daley GQ. Lin28: primal regulator of growth and metabolism in stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bolton RK, et al. Regenerative Growth in Drosophila Imaginal Discs Is Regulated by Wingless and Myc. Dev Cell. 2009;16:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulem P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies sequence variants on 6q21 associated with age at menarche. Nat Genet. 2009;41:734–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan SR, et al. Selective blockade of miRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widén E, et al. Distinct variants at LIN28B influence growth in height from birth to adulthood. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:773–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert ML, et al. LIN28 Binds Messenger RNAs at GGAGA Motifs and Regulates Splicing Factor Abundance. Mol Cell. 2012;48:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, et al. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Moss E. Temporally regulated expression of Lin-28 in diverse tissues of the developing mouse. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:719–726. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S, et al. Dynamic gene expression of Lin-28 during embryonic development in mouse and chicken. Gene Expr Patterns. 2008;8:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HE, et al. Gross morphological analysis of limb regeneration in postmetamorphic adult Ambystoma. Anat Rec. 1983;206:295–306. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092060308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, et al. Lin28a transgenic mice manifest size and puberty phenotypes identified in human genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2010;42:9–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, et al. The Lin28/let-7 axis regulates glucose metabolism. Cell. 2011;147:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.