Abstract

Background

Mitochondrial alterations occur in skeletal muscle fibers throughout the normal aging process, resulting from increased accumulation of reactive oxide species (ROS). These result in respiratory chain abnormalities which decrease the oxidative capacity of muscle fibers, leading to decreased contractile force, sarcopenia, or fiber necrosis. Intrinsic laryngeal muscles are a cranial muscle group which possess some distinctive genotypic, phenotypic and physiologic properties. Their susceptibility to mitochondrial alterations resulting from biological processes that increase levels of oxidative stress may be one of these distinctive characteristics.

Objectives

The incidence of COX deficiency (COX−) was determined in human posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA) muscle, in comparison to the human thyrohyoid (TH) muscle, an extrinsic laryngeal muscle that served as “control” muscle. Ten PCA and 10 TH muscles were harvested post laryngectomy from 10 subjects ranging in age from 55–86 years. Differences in COX− were compared within and between muscle types using tissue section staining and standard morphometric analysis.

Results and Conclusions

COX− fibers were identified in both the PCA and TH muscle. The PCA muscle had ten times as may affected fibers as the TH muscle, with significant differences in COX− found between muscle type and fiber type (p = .003). Almost all of this effect was the result of elevated levels of COX deficiency in type I fibers from the PCA muscle (p = .002) that showed a strong positive correlation with increased age. These results suggest that increased mitochondrial alterations may occur in the PCA muscle during normal aging.

Keywords: Laryngeal muscles, Cytochrome-c oxidase, aging, posterior cricoarytenoid muscle

INTRODUCTION

Normal aging produces vocal changes most commonly demonstrated as a steady decline in mean fundamental frequency of the speaking voice in females, an increase in fundamental frequency in males, presbyphonia (loss of muscle mass) and dysphonia.1 These changes are brought about by a number of general factors, including lowering of laryngeal position,2 lengthening of the vocal tract,3 and stiffening of vocal folds.4, 5 One key aspect of aging is the gradual loss of neuromuscular function, seen functionally as weaker, slower and less fatigue resistant muscles6 which result in compromised voice production and airway protection.7 Most investigations on muscle aging in the larynx have been conducted on the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle given its key role as a vocal fold adductor and tensor.6–11 Limited research exists, however, on the posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA) muscle, the sole vocal fold abductor. Age-related metabolic changes of the PCA muscle may affect the functioning of the vocal folds during speech and respiration due to a reduction in the ability to abduct the vocal folds, producing a smaller functional glottal space in the elderly.

The loss of muscle mass that occurs during aging is termed sarcopenia,12 and is driven by systemic age-related changes in hormones, nutrition, metabolism, and immunology.13,14 The size of type II (fast contracting) muscle fibers may be reduced by up to 50% in old age, while type I (slow contracting) fiber areas appear to be only modestly affected.15 The most significant reductions in muscle mass, however, come from the loss of total fiber number, estimated in human vastus lateralis to approximate 50% by the ninth decade. The largest contribution to age-related muscle fiber decrease is motor neuron necrosis and, consequently motor unit loss,16,17 especially in the type II units. Laryngeal muscles normally have higher innervation ratios (increased motor neurons and smaller motor units) than larger skeletal muscles and, perhaps respond to neuron necrosis in a somewhat different fashion than larger muscles. Laryngeal synkinesis18,19 is a process, somewhat specific to laryngeal muscles, by which motor neuron axonal sprouting remodels motor unit size and recruitment during nerve necrosis, resulting in inappropriate muscle contraction. A further complication, at least in human TA muscle, is that type I motor units may be preferentially damaged with age, as evidenced by increased rates of regeneration, necrosis and muscle fiber loss relative to type II motor units9–11 For PCA muscle some reports demonstrate no age-related changes in type I fiber type morphology,20 while others find significant decreases in type I fiber diameters.21 With age in laryngeal muscles, therefore, fiber number and size change but the nerve and muscle interactions through which sarcopenia develops are somewhat different than in limb muscles.

Another factor involved in age-related muscle changes is oxidative stress. Most biochemical and morphological energy deficits in aging muscle are related to reactive oxygen species (ROS) (i.e., oxygen free radicals),22 which make the mitochondrial genome susceptible to gene deletions and mutations.23 The circular mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) lacks histone protection and has limited repair systems, making the error rate 10 times greater than nuclear DNA.24 Damage to mtDNA comes in the form of point and/or deletion mutations or reduced mt mRNA levels. Of the respiratory chain enzyme subunits coded by the mitochondrial genome, cytochrome-c oxidase (COX) or respiratory enzyme complex IV demonstrates by far the highest mutation rate. COX is vital to cell respiration since it is primarily responsible for the transfer of the electrons from the respiratory chain enzyme complex to molecular oxygen. Over time ROS accumulation exceeds a critical cellular threshold which may be demonstrated as a histochemical deficiency of the protein (COX−).25,26 Further, mtDNA have no true mechanism to recover from oxidative stress when mutations occur.27 Respiratory chain abnormalities decrease the oxidative capacity of muscle fibers, reducing overall muscle contractile force and fatigue resistance. These abnormalities also play a role in sarcopenia by diminishing the size and vitality of affected fibers.28

One study of respiratory chain defects in human laryngeal muscle by Kersing & Jennekens29 estimated that oxidative damage affects approximately 20% of all fibers in the TA muscle by the 6th decade of life. Data from another group, however, has indicated that approximately 3% of fibers are damaged in human skeletal muscle during this decade,30 so that further investigation is needed to confirm findings in TA muscle. One possibility is that some of the subjects from whom muscle was taken in Kersing & Jennekens’s study were smokers. ROS can be generated from various sources within the cell such as the mitochondrial electron transport system (ETS), phagocytic cells, and oxidant enzymes.31 Included in the exogenous sources of ROS are drug oxidations, ionizing radiation, redox-cycling substances and cigarette smoke.32 The presence of the free radicals in cigarette smoke have been implicated in cancer,33 and also might have some specific cellular affects on the muscle tissue lying just beneath the lining the glottis. The present study investigated oxidative damage in human PCA muscle since it does not approximate the glottal lining, but rather is located external to the cartilaginous and fibrous portions of the larynx. In addition an extrinsic laryngeal muscle, the thyrohyoid (TH), was analyzed along with PCA to serve as an internal control. The TH lies external to the larynx and is very likely to have similar exposure to ROS from cigarette smoke as PCA. Choosing the thyrohyoid muscle also allowed us to detect differences in oxidative damage between intrinsic and extrinsic laryngeal muscles. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to determine the extent of age-related oxidative damage in human PCA muscle. Given the unusual aging demonstrated previously in TA type I fibers,29 a second aim of this study was to determine if the same pattern of differences exist between type I and type II muscle fibers for both PCA and extrinsic laryngeal muscles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and Biopsies

Whole posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA) and thyrohyoid (TH) muscles were harvested from ten patients undergoing total laryngectomy due to laryngeal carcninoma (Approval #991280). Subjects ranged in age from 55–86 years with a mean age of 68 years. Vocal fold function was diagnosed as normal by videolaryngoscopic inspection prior to surgery. Immediately after removal of the larynx, the PCA muscle was exposed by resection of the postcricoid mucosa and the fibrous tissue that divides the horizontal and vertical compartments. The muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage (insertion point for PCA) was marked with a suture which was then used to bisect the horizontal and vertical compartments. Each compartment was dissected from origin to insertion and positioned in its native in vivo orientation on gauze moistened with cold phosphate-buffered saline. Only two of the ten muscle samples were from the vertical compartment so that direct comparison between the muscle compartments was not examined in this study. A portion of the TH muscle was harvested along with the PCA samples and used as a control. The PCA and TH samples were orientated in cross-section, mounted in Tissue-Tech™ medium and snap frozen in isopentane cooled by dry ice to −70°C to produce one composite tissue block for each subject. Series of 10μm cryosections were taken in differing regions of the muscle composite blocks in areas of good morphology that provided sufficient numbers of fibers (i.e., 1200–4500 in PCA and 850–4000 in TH) for analysis. At least three serial section series were collected from each composite block with at least 200μm of separation between the end of one series and the start of another to extensively assess phenotype and COX activity along entire individual fibers.

Although muscle biopsies were harvested from individuals who had undergone a course of radiation for laryngeal carcinoma, none of the tissue samples showed signs of malignancy or severe dysplasia.

Staining Procedures

Fiber-type immunohistochemistry

Muscle fibers were classified as type I (slow) and type II (fast) by antibody staining of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms in serial sections using an indirect immunoperoxidase method.34 Primary antibody reactivity was detected by either a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody or a biotin-labeled secondary antibody visualized by an avidin-conjugated peroxidase. MyHC-specific antibodies included anti-Type I monoclonal (slow skeletal MyHC – Sigma Aldrich clone NOQ7) and an anti-fast monoclonal (fast skeletal IIA, IIB & IIX MyHC – Sigma Aldrich clone MY-32).

Histochemical identification of mitochondrial abnormalities

COX activity was analyzed in sections serial to the antibody staining to identify COX deficiency among the fiber types. Sections were incubated for 1 hour in 0.5mg/ml 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, 1mg/ml cytochrome c, 75mg/ml sucrose and approximately 20μg/ml of catalase in 50mM phosphate buffer, pH7.4 followed by a quick water rinse and dehydration in increasing concentrations of ethanol (50%–100%). Fibers containing COX activity stain brown whereas pale or no staining indicate a deficiency of complex IV of the electron transport system.35 Type I slow oxidative (SO) fibers stain darkest for COX whereas type II fast oxidative glycolytic (FOG) and fast glycolytic (FG) fibers stain medium to pale by these methods. Histochemical staining for succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)36 was used complementary to serial sections of COX staining to further identify the fibers with mitochondrial deficiency. SDH expression is nuclear encoded and up-regulation of its activity indicates a compensatory cellular response to disruption of the electron transport system (ETS) in mitochondria. Briefly, sections were incubated in 27 mg/ml sodium succinate, 1mg/ml nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 0.2M phosphate buffer, pH 7.6 for 1hr at 37°C followed by washes in increasing and decreasing concentrations of 30% to 90% acetone to remove unbound NBT. Resultant purple staining at sites of mitochondria is darker in type I than in type II fibers. Very dark staining indicates hyperactivity of SDH that sometimes occurs in COX− fibers.

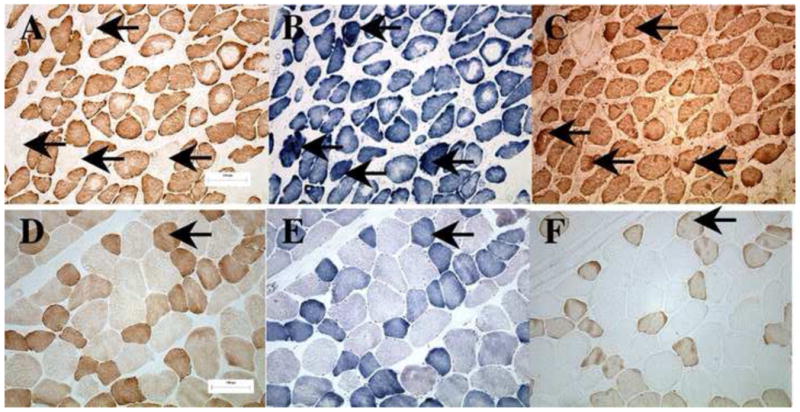

Data Collection

Stained sections of the PCA and strap muscles were viewed by light microscopy (Leica DMR™ microscope) and images were analyzed using Image ProPlus 4.5.1™ software. Total numbers of fibers were counted in the same area of each section for COX and SDH activity and for type I and type II immunoreactivity. Type I fibers that stained dark for COX and SDH, and type II fibers that stained light to moderately for COX and moderately to dark for SDH were considered normal. Only type I fibers that were pale or did not stain for COX and displayed hyperactive staining for SDH, and type II fibers that displayed little or no staining for COX but were moderate to darkly stained for SDH were considered COX−. Fiber typing of serial sections was always done after the identification of COX− to control for experimental bias. Staining and fiber classification are demonstrated in Figure 1 and reliability of fiber classification was analyzed statistically. Type IIA (Fast Oxidative Glycolytic) and type IIX (Fast Glycolytic) subtypes could be differentiated by COX and SDH histochemistry but were counted together as type II fibers for comparison with type I. The distribution of all COX− fibers was calculated as percent of the total number of fibers counted in each biopsy for comparisons between PCA and TH muscle of the individual patients. Data were also calculated as the percent of COX− fibers within the type I and type II classes in muscles of each patient. The data were analyzed to test for mean COX fiber percent differences between muscle type and fiber type using a 2 × 2 within-cases analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Figure 1.

Staining for serial sections from PCA (panels A–C) and TH (panels D–F) of a 69 year old male. Stained for cytochrome c oxidase (COX) (panels A and D), succinate dehydrogenase (SHD) (panels B and E), and type I myosin antibody (panels C and F). Arrows in the top (panels A–C) mark COX-fibers which are pale for COX stain, hyperactive for SDH stain, and classified as type I fibers by myosin antibody reactivity. The bottom panels show a characteristic representation of TH muscle fibers without COX-fibers. Arrows in bottom (panels D–F) identify a normal type I fiber with positive COX and SDH activity.

Reliability

Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability measures were conducted to determine the within and between investigator consistency in identifying cytochrome c oxidase deficient type I and type II fibers. Reliability coefficients were estimated using a Pearson product-moment correlation analysis and confirmed with a test for bias. The intra-rater reliability coefficient was r = 1 for the PCA muscle at time one and time two indicating a perfect correlation. Lack of rater bias over time was supported by a low mean difference (.00046, p = .069). The intra-rater reliability coefficient for thryohyoid muscle at time one and time two showed a low correlation (r = 0.354). The mean difference for thyrohyoid muscle at time one and time two was extremely low (−.00048, p = .374) and a paired t-test showed no significant difference (t = −1.0, p = .374). These results indicate that the intra-rater reliability for the thyrohyoid muscle was reliable and the measures unbiased. Inter-rater reliability coefficients for the PCA muscle at time one and time two showed a high correlation (r = 0.995) and a low mean difference (−.00027, p = 347) indicating no bias.

RESULTS

Both normal and COX− type I and type II fibers were detected in the PCA and TH muscles by the combination of myosin antibody and histochemical staining (Fig. 1). Although the PCA muscle had more connective tissue and smaller and more heterogeneously shaped fibers than the TH, fiber type and COX deficiency were routinely identified with the COX− fibers staining pale for cytochrome c oxidase and almost always dark blue for SDH (Fig. 1, bold arrows). COX deficiency did not affect the myosin antibody staining so that type I and type II fiber phenotypes appeared normal. Because COX deficiency usually occurs in a focal segment rather than along the entire length of a skeletal muscle fiber where the COX− segment seldom exceeds 200μm in length and more than one nonadjacent segment in a single muscle fiber may be affected37, serial sections were collected and analyzed from at least three areas that were more than 200 μm apart in each composite block.

Approximately 2500 individual fibers were analyzed from each PCA muscle sample and 1800 muscle fibers from each TH sample (Table 1). Differences in sampling resulted from the smaller fiber diameter in PCA samples which produced greater fiber density per given area of tissue section. As a percentage of total fibers counted, COX− fibers were almost ten times more prevalent in the PCA muscle compared to the TH (Table 1). In the PCA samples, the total mean percentage of type I fibers was approximately 60% and type II fibers was 40% (Table 2). There was however variation in fiber type distribution between individual PCA muscles, ranging from almost 90% type I fibers and 10% type II fibers for subjects 1 and 2, to 40% type I fibers and 60% type II fibers for subjects 6 and 10 (Table 2). In contrast, the total mean percentages were consistently 58% for type I fibers and 42% for type II fibers in the TH control muscle (Table 2). Overall, biopsies from both PCA and TH muscle displayed normal human skeletal muscle fiber type variability, yet quite similar fiber-type percent distributions.

Table 1.

COX Deficiency: PCA and IH Compared

| Total Fiber n | COX n | COX % | Total Fiber n | COX n | COX % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA-age | TH | ||||||

| 1 – 55 | 2875 | 14 | 0.5 | 1 | 2054 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 – 63 | 1204 | 17 | 1.4 | 2 | 1570 | 9 | 0.57 |

| 3 – 63 | 2357 | 10 | 0.4 | 3 | 853 | 3 | 0.35 |

| 4 – 66 | 2443 | 87 | 3.6 | 4 | 1012 | 5 | 0.49 |

| 5 – 67 | 4043 | 68 | 1.7 | 5 | 838 | 1 | 0.12 |

| 6 – 68 | 4535 | 38 | 0.8 | 6 | 1363 | 2 | 0.15 |

| 7 – 69 | 3334 | 96 | 2.9 | 7 | 2248 | 2 | 0.08 |

| 8 – 73 | 2986 | 37 | 1.2 | 8 | 1183 | 2 | 0.17 |

| 9 – 78 | 2286 | 85 | 3.7 | 9 | 2716 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 10 – 86 | 1578 | 39 | 2.5 | 10 | 4182 | 24 | 0.57 |

| mean | 2515 | 49 | 1.72 ± 0.12 | 1802 | 5 | 0.25 ± 0.23 | |

Table 2.

COX Deficiency & Fiber Type Distribution

| Fibers | Fibers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Type II | Type I | Type II | ||||||

| n | % COX | n | % COX | n | % COX | n | % COX | ||

| PCA-age | TH | ||||||||

| 1 – 55 | 2438 | 0.5 | 437 | 0.23 | 1 | 1152 | 0 | 902 | 0 |

| 2 – 63 | 1044 | 1.5 | 160 | 0 | 2 | 1046 | 0.67 | 524 | 0.38 |

| 3 – 63 | 1404 | 0.61 | 953 | 0.11 | 3 | 393 | 0 | 460 | 0.65 |

| 4 – 66 | 2076 | 4.0 | 367 | 1.09 | 4 | 512 | 0.39 | 500 | 0.6 |

| 5 – 67 | 2000 | 2.35 | 2043 | 1.03 | 5 | 313 | 0.32 | 525 | 0 |

| 6 – 68 | 1788 | 1.1 | 2747 | 0.55 | 6 | 1152 | 0 | 782 | 0.13 |

| 7 – 69 | 2292 | 3.4 | 1042 | 1.64 | 7 | 1317 | 0.15 | 931 | 0 |

| 8 – 73 | 1111 | 3.1 | 1875 | 0.11 | 8 | 889 | 0.11 | 294 | 0.34 |

| 9 – 78 | 1193 | 6.0 | 1093 | 1.28 | 9 | 1541 | 0 | 1175 | 0.09 |

| 10 – 86 | 605 | 4.62 | 973 | 1.13 | 10 | 2540 | 0.43 | 1642 | 0.79 |

| Mean | 1475 | 2.72 ± 1.83 | 996 | 0.72 ± 0.59 | 1086 | 0.20 ± 0.23 | 774 | 0.29 ± 0.30 | |

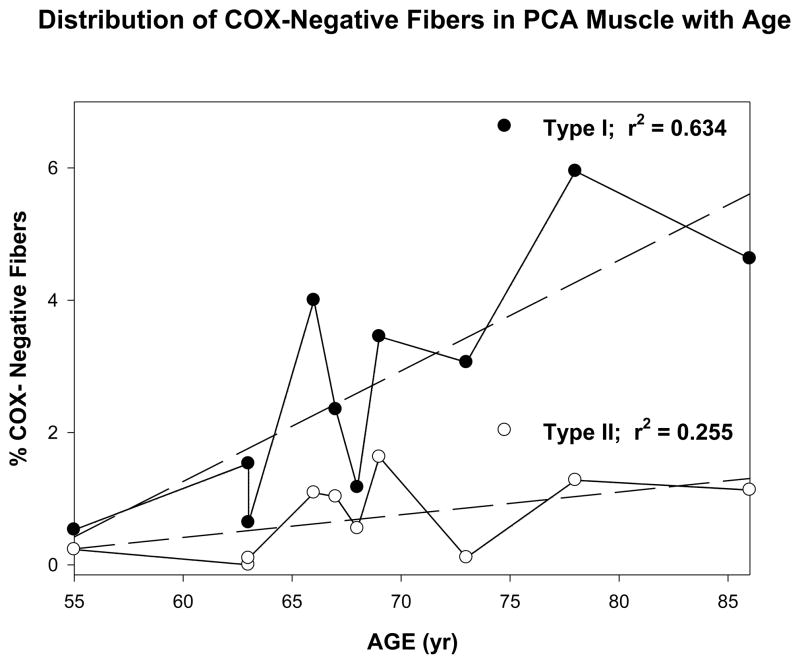

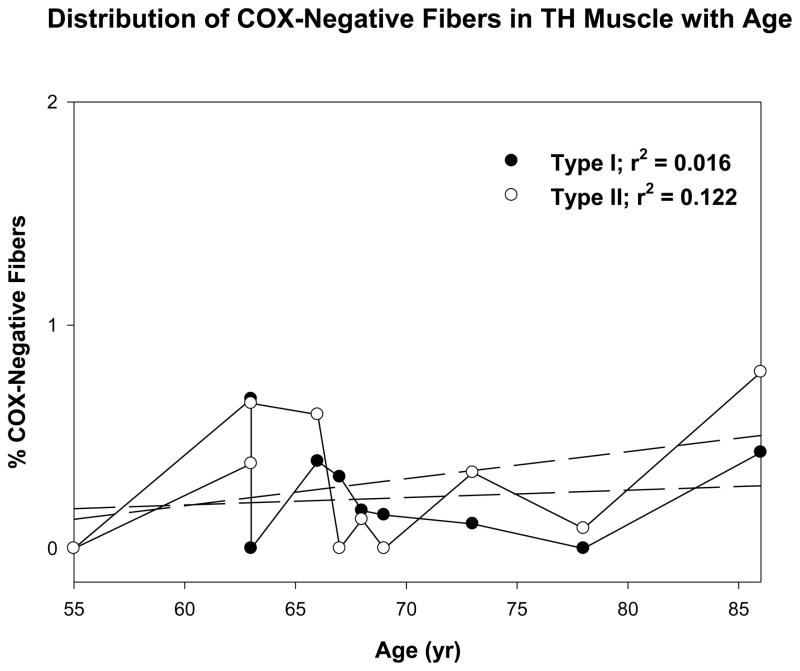

The percent COX− type-I and type-II fibers were plotted relative to the age of the subjects for PCA muscle (Fig. 2) and TH muscle (Fig. 3) and the mean COX− fiber percentages were analyzed to test for statistical differences between muscle type and fiber type using a 2 × 2 within-cases analysis of variance (ANOVA). Both the main effects for muscle type and fiber type differences were statistically significant (p = .003) and (p = .003), respectively. The muscle by fiber type interaction effect was also significant (p = .002). Post hoc tests for simple main effects demonstrated significantly different COX deficiency, but this difference was not observed between type I and II fibers in the TH muscle (p = .360). As shown in Figure 3, however, significant differences between the PCA and TH muscles were found in type I fibers (p = .002), but not in type II fibers (p = .093) where no significant differences were observed between the two muscles.

Figure 2.

Figure shows the distribution of COX-negative fibers in the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle with age. Dark circles represent type I fibers. White circles represent type II fibers.

Figure 3.

Figure shows the distribution of COX-negative fibers in the thyrohyoid muscle with age. Dark circles represent type I fibers. White circles represent type II fibers.

Of particular interest is the question of how age affects the development of COX deficiency in laryngeal muscles, since this process is considered to be a normal occurrence in the aging of human skeletal muscle fibers. The association between age and COX deficiency for the fiber types in both muscles, therefore, was compared using Pearson correlations. Age was not associated as statistically significant with COX deficiency in type II fibers from the PCA muscle (p = .069) or both type I and II fibers from the TH muscle (p = .362 and .161, respectively). Type I fibers from the PCA muscle, however, demonstrated significant increases in COX deficiency with age (p = .003). Although preliminary, this result demonstrates that Type I fibers in the laryngeal muscle are predisposed to oxidative damage and metabolic deficits with age. The scatter plots with regression lines and the r2 values for these analyses are given in Figures 2 and 3.

A nonparametric approach was completed to confirm the results of the parametric statistics used to assess the data. The nonparametric set of procedures does not contain anything as rich as ANOVA/MANOVA in the types of designs that can be analyzed. Anything as simple as a 2 × 2 must be done as a series of pairwise tests. These were done with the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test which is used for paired (within cases) data. The nonparametric tests are in accord with the ANOVA results in terms of the statistical conclusions, confirming the results of the initial parametric statistics.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in the PCA muscle compared to TH muscle was investigated to determine if differences exist between human intrinsic and extrinsic laryngeal muscles. By sampling these muscles from the same subjects at the time of laryngectomy, variances were controlled which might occur from age or environmental radical oxide exposure. Subjects were from the 6th to 9th decade of life, with ages of the majority (n = 6) distributed evenly throughout the 7th decade. The fiber type distribution between samples was equitable, with the PCA containing 60 percent type I fibers and 40 percent type II fibers compared to 58 percent and 42 percent in the TH muscles. The fibers sampled from PCA muscle were ten times more likely to be affected by disrupted oxidative metabolism than TH muscle fibers. The severity of this effect in the PCA was unevenly distributed between fiber types with type I fibers being three times as likely to be affected as type II fibers. Type II fibers in the TH muscle displayed greater defects than type I fibers, but these differences were very modest. Overall, oxidative defects were much more pronounced in the intrinsic laryngeal muscle type I fiber population, and this distinction increased with age.

The COX histochemical stain can identify an area in which a mtDNA mutation has disrupted normal production of cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) in the oxidative enzyme chain. COX staining readily identifies the metabolic deficiency when the total number of mitochondria affected by mutation increase into the 60–90% range.38 The deficiency is typically limited to a solitary and circumscribed area along the fiber length, usually not greater than 200μm as measured through extensive serial sections in rat limb muscle.28 When first considered, the percentage of COX− fibers sampled appear relatively low, within approximately 0.2 to 2.0% of total fibers. The method used in this study estimates the average number of affected fibers from the mid sectional area of the muscle, and does not take into account affected segments in other fibers at different anatomic levels in the muscle. If the muscles were sampled along their entire length the overall percentage of affected fibers would likely be increased. Three dimensional volumetric studies of rat limb muscle have achieved this objective,40 with an estimate of approximately 15% of the total fiber population affected by COX deficiency in old age.

The percentages reported in the present study are in general agreement with studies of other human40–42 and monkey43 muscles over similar age ranges, which demonstrated an association to significant biologic effects, including loss of fiber number and overall muscle mass, at a similar rate of incidence. Failure of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes may lead to fiber necrosis or apoptosis,42 and removal of the cell from the tissue pool over a period of approximately two years. Any temporal cross sectional estimate of COX deficiency then, can only take into account affected cells at that time point, not those already lost or those that would be lost at a future time point. If 2% of PCA muscle fibers are affected in the subjects at times in the 7th decade of life, a cumulative loss of approximately 10% of total fiber number can be estimated over this entire decade. In the 5th decade there are only modest affects in both intrinsic and extrinsic laryngeal muscles, but from the 6th decade onward the intrinsic muscles show significant cumulative rates of COX deficiency.

Data from the present study however, can only estimate the biological importance of the condition since the actual fate of COX fibers in human laryngeal muscles is not certain at this point. The glycolytic pathway for energy metabolism remains functional in the affected muscle fibers, and produces sufficient energy to maintain the structural integrity of the cell.44 In addition, the mitochondrial organelle membranes also remain intact.45 With COX deficiency, a localized fiber area becomes disrupted, but this may not necessarily lead to cell death. As an example, in contraction induced injury a focal internal mechanical disruption occurs to individual sarcomeres during lengthening contractions, most commonly in elderly individuals with frail muscles.46 The damaged area is sealed off and complete healing may take several weeks, or incomplete healing may persist leading to loss of fiber size and force.47 It remains plausible that similar processes occur in COX− regions such that individual fibers may recover, atrophies and is lost, or persists with chronic decreases in size and force. This latter process has been described for COX− fibers,28 and most certainly contributes to sarcopenia in aging muscle. If the disrupted region does not completely heal, the fiber would effectively be removed from force generation since the functional segments would stretch the disrupted region rather than shortening the entire fiber during contraction.

Muscle fiber responses to oxidative stress, contraction induced injury, denervation and age-related changes in size ultimately rely upon their regenerative capacity.48 After incorporation into the myofilament, myonuclei lose their ability to divide. Skeletal muscle, at equilibrium in the adult state, maintains a constant ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic mass. A loss of myonuclei without replacement results in a concomitant decreased in fiber size to maintain the equilibrium. Normally, satellite cells, located on the external surface of the sarcolemma, retain mitotic potential and are routinely recruited into the myonuclear pool to replace necrotic nuclei and maintain cell size, but aging diminishes the remodeling capacity of muscle fibers.49 Some cranial muscle groups, however, have greater intrinsic remodeling capacity, as evidenced by the ability of extraocular muscles to resist myonecrosis during the course of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.50 Even under normal healthy conditions these muscles maintain continuous myofiber remodeling.51 Similar robust remodeling capacities have been demonstrated in laryngeal myofibers52 which also possess a characteristic ability to withstand long periods of denervation with favorable recovery rates.53 A heightened regenerative capacity of the fibers in human intrinsic laryngeal muscles may possibility buffer the myonecrotic effects of oxidative damage as compared with extrinsic laryngeal and limb muscles. Findings from the present study might suggest that the rate of COX deficiency in type I and type II fibers of human PCA may be similar, but the regenerative capacity of type I fibers may be enhanced in comparison to type II fibers.

Alternatively, the increase in oxidative deficiencies identified in the type I fibers of human PCA muscle may simply indicate a higher incidence of damage and necrosis. Using sterological confocal laser scanning microscopy, Malmgren and colleagues have demonstrated higher age-related levels of loss,9 myonuclear and satellite cell apoptosis,10 and fiber regeneration11 in the type I fiber population of human thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle. The data from the present study could imply that the mechanism for these processes, at least in part, comes from the tendency for type I fibers in intrinsic laryngeal muscles to incur significantly elevated levels of mt DNA mutations. Since the decrease of skeletal muscle mass with age has been observed primarily from losses in the type II fiber populations54, the preferential age-related changes in type-I fibers reported should be considered preliminary. Nevertheless, the etiology for fiber loss in aging is produced by loss of type II motor units,55, 56 and accompanied by the reorganization of the remaining motor units.57 Through axonal sprouting, healthy motor neurons incorporate some denervated fibers into their unit,58 producing type I units with greater numbers of fibers.56 A portion of the apoptosis identified in human TA muscle may, therefore, have come from reorganization of type I motor units since the proportion of apoptotic nuclei increase with denervation.59–60 Likewise the continuous myofiber remodeling found in extraocular muscle persists into old age,61 necessitating elevated levels of apoptosis to maintain cell size during this period.50

Results of this type could lead to increased fatigue rates in the PCA muscle with increased age. Clinically there is evidence that as some people age, their ability to abduct the vocal folds completely and simultaneously decreases. A reduction in the metabolic capacity of the PCA with age may be a contributing factor to this phenomenon, and would have implications to coordinating phonation with breathing and maintaining an open airway during exertion. Future research should evaluate these findings to determine if there is a correlation to the results found within this study. Difficulty during extended phonation in speaking and singing also may be affected due to increased fatigue rates in the PCA in the aging population. Although the results of this study are preliminary, further research will help to design voice therapy for endurance and increased range of motion in the intrinsic laryngeal muscles as individuals age.

LIMITATIONS

Some limitations exist in the present study. One limitation was that the vertical belly of the PCA was not differentiated from the horizontal belly in this study. Continued research differentiating these bellies may provide more information on age-related affects of the PCA to voice because of the vertical belly’s role in extended phonation. The subjects also were post-laryngectomy and all had a smoking history. Although the PCA was chosen because of its location away from the glottal space and direct contact with the carcinogens in the smoke, smoke is a ROS and may have caused changes to the muscle fibers. Although PCA muscle was compared to a muscle not contacted by cigarette smoke, future research should include individuals without a smoking history. Another consideration for future research is that the individuals that were tested all had a course of radiation before their surgery. Although there were no signs of dysplasia in any of the muscle fibers that were tested, one of the reasons the control muscle was taken from each participant to compare to the muscle that was tested was because both would have been exposed to the radiation. If no difference had been found between the two muscles, then the exposure to radiation may have been a factor. Future research should also include more participants and a wider age rage to compare.

CONCLUSION

Although this study provides only a preliminary investigation of metabolic changes in type I and type II fibers in the PCA muscle during aging, the findings imply a significant impact on PCA muscle function with age. Type I muscles fibers are slow-twitch and nonfatigable while type II fibers are fast-twitch and fatigable. With a greater portion of type I muscle fibers affected during aging in the PCA, as shown in this study, the fatigue rate of PCA may increase especially during extended phonation tasks like speaking and singing. The ability of the vocal folds to abduct completely during these phonation tasks may become compromised and the individual may begin to have difficulty regulating respiration (inhaling) with an extended speech task because of the reduction in the airway at the level of the glottis. Future research should address the functional implication of oxidative deficiencies on the intrinsic laryngeal muscles.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sataloff RT, Rosen DC, Hawkshaw M, Spiegel JR. The aging adult voice. J Voice. 1997;11:156–160. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(97)80072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilder C. Vocal aging. In: Weinberg B, Lawrence V, editors. Transcripts of the Seventh Symposium Care of the Professional Voice. Part II. Life-span Changes in the Human Voice. New York: The Voice Foundation; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linville SE, Rens J. Vocal tract resonance analysis of aging voice using long-term average spectra. J Voice. 2001;15:323–330. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(01)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahane JC. A survey of age-related changes in the connective tissue of the human adult larynx. In: bless DM, Abbs JH, editors. Vocal cord physiology. San Diego: College Hill Press; 1983. pp. 44–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond TH, Gray SD, Butler JE. Age- and gender-related collagen distribution in human vocal folds. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:913–920. doi: 10.1177/000348940010901004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMullen CA, Andrade FH. Contractile dysfunction and altered metabolic profiles of the aging rat thyroartenoid muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:602–608. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01066.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward PH, Colton R, McConnell F. Aging of the voice and swallowing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100:283–286. doi: 10.1177/019459988910000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner NP, Suzuki T, Lee K, Sewall GK, Heisey DM. Neuromuscular junction changes in aged rat thyroarytenoid muscle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:579–586. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malmgren LT, Fischer PJ, Bookman LM, Uno T. Age-related changes in muscle fiber types in the human thyroarytenoid muscle: an immunohistochemical and sterological study using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:441–451. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malmagren LT, Jones CE, Bookman LM. Muscle fiber and satellite cell aptosis in the aging human thyroarytenoid muscle: A sterological study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:34–9. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.116449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malmgren LT, Lovice DB, Kaufman MR. Age-related changes in muscle fiber regeneration in the human thyroarytenoid muscle. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:851–856. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg IH. Summary comments. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1231–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roubenoff R, Hughes VA. Sarcopenia:current concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M20–M26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welle S. Cellular and molecular basis of are-related sarcopenia. Can J Appl Physiol. 2002;27:19–41. doi: 10.1139/h02-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doherty TJ. Invited Review:Aging and sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1717–1727. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown WF. A method for estimating the number of motor units in thenar muscles and the changes in motor unit count with ageing. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;35:845–852. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.35.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansved T, Larsson L. Effects of ageing on enzyme-histochemical, morphometrical and contractile properties of the soleus muscle in the rat. J Neurol Sci. 1989;93:105–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crumley RL. Laryngeal synkinesis revisited. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:365–371. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maronian NC, Robinson L, Waugh P, Hillel AD. A new electromyographic definition of laryngeal synkinesis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:877–886. doi: 10.1177/000348940411301106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T, Connor NP, Lee K, Bless DM, Ford CN, Inagi K. Age-related alterations in myosin heavy chain isoforms in rat intrinsic laryngeal muscles. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:962–967. doi: 10.1177/000348940211101102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodeno MT, Sanchez-Fernandez JM, Rivera-Pomar JM. Histochemical and morphometrical ageing changes in human vocal cord muscles. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113:445–449. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sastre J, Pallardo FV, Garcia de la Asuncion J, Vina J. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and aging. Free Radical Res. 2000;32:189–198. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalra J, Chaudhary AK, Prasad K. Increased production of oxygen free radicals in cigarette smoke. Inter J Experiment Patho. 1991;72:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown WM, George MJ, Wilson AC. Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1971;76:1969–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chinnery PF, Howel D, Trunbull DM, Johnson MA. Clinical progression of mitochondrial myopathy is associated with the randon accumulation of cytochrome c oxidase negative skeletal muscle fibres. J Neurol Sci. 2003;211:63–66. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fayet G, Jansson M, Sternberg D, Moslemi A-R, Blondy P, Lombes A. Ageing muscle: clonoal expansions of mitochondrial DNA point mutations and deletions cause focal impairment of mitochondrial function. Neuromusc Disord. 2005;12:484–493. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copeland WC, Ponamarev MV, Nguyen D, Kunkel TA, Longley MJ. Mutations in DNA polymerase gamma cause error prone DNA synthesis in human mitochondrial disorders. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2003;50:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wanagat J, Cao A, Pranali P, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations colocalize with segmental electron transport system abnormalities, muscle fiber atrophy, fiber splitting, and oxidative damage in sarcopenia. FASEB J. 2001;15:322–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0320com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kersing W, Jennekens FGI. Age-related changes in human thyroarytenoid muscles: a histological and histochemical study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryn. 2004;261:386–392. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0702-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne E, Dennett X. Respiratory chain failure in adult muscle fibres: relationship with ageing and possible implications for the neuronal pool. Mutation Res. 1992;275:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90017-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Z, Wanagat J, McKiernan SH, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations are concomitant with ragged red regions of individual, aged muscle fibers: analysis by laser-capture microdissection. Nucleic Acid Res. 2001;29:4502–4508. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cross CE, Halliwell B, Borish E, Pryor WA, Ames BM, Sal RL. Oxygen radicals and human disease. Annal Internal Med. 1987;107:526–545. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-4-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Church DF, Pryor WA. Free-radical chemistry of cigarette smoke and its toxicological implications. Environment Health Perspect. 1985;64:111–126. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8564111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandon CA, Rosen C, Georgelis G, Horton MJ, Sciote JJ. Muscle Fiber Type Composition and Effects of Vocal Fold Immobilization on the Two Compartments of the Human Posterior Cricoarytenoid: A case study of four patients. J Voice. 2003;17:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(03)00027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pesce V, Cormio A, Fracasso F, Vecchiet J, Felzani G, Lezza AMS. Age-related mitochondrial genotypic and phenotypic alterations in human skeletal muscle. Free Radical Biol Med. 2001;30:1223–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nachlas M, Tsou MK, deSouza E, Cheng C, Seligman AM. Cytochemical demonstration of succinic acid dehydrogenase by use of a new p-nitrophenyl substituted ditetriazole. J Histochem Cytochem. 1957;5:420–436. doi: 10.1177/5.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto M, Nonaka I. Skeletal muscle pathology in chronic progressive external opthalmoplegia with ragged-red fibers. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988;76:558–563. doi: 10.1007/BF00689593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chomyn A, Meola G, Bresolin N, Lai ST. In vitro genetic transfer of protein synthesis and respiration defects to mitochondrial DNA-less cells with myopathy-patient mitochondria. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2236–2244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linville SE, Rens J. Vocal tract resonance analysis of aging voice using long-term average spectra. J Voice. 2001;15:323–330. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(01)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller-Hoecker J. Cytochrome c oxidase deficient fibers in the limb and diaphragm of man without muscular disease: an age-related alteration. J Neruol Sci. 1990;100:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barron MJ, Chinnery PF, Howel D, Blakely EL, Schaefer AM, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Cytochrome c oxidase deficient muscle fibres: substantial variation in their proportions within skeletal muscles from patients with mitochondrial myopathy. Neuromusc Disord. 2005;15:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byrne E, Dennett X. Respiratory chain failure in adult muscle fibres: relationship with ageing and possible implications for the neuronal pool. Mutation Res. 1992;275:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90017-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muller-Hocker J, Schafer S, Link TA, Possekel S, Hammer C. Defects of the respiratory chain in various tissues of old monkeys: a cytochemical-immunochemical study. J Neurol Sci. 1996;86:197–213. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(95)01692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King MP, Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science. 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skowronek P, Harerkamp O, Rodel G. A florescence-microscope and flow-cytometric study of HeLa cells with an experimentally induced respiratory deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:991–998. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCully KK, Kaulkner JA. Injury to skeletal muscle fibers of mice following lengthening contractions. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59:119–26. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rader EP, Faulkner JA. Effect of aging on the recovery following contraction-induced injury in muscles of female mice. J Appl Physiol. 1996;101:887–92. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00380.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2004:209–38. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlson BM. Factors influencing the repair and adaptation of muscles in aged individuals: satellite cells and innervation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:96–100. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.special_issue.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrade FH, Proter JD, Kaminski HJ. Eye muscles sparing by the muscular dystrophies: lessons to be learned? Microsc Res Technol. 2000;8:192–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000201/15)48:3/4<192::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLoon LK, Rowe J, Wirtschafter J, McCormick KM. Continuous myofiber remodeling in uninjured extraocular myofibers; myonuclear turnover and evidence for aptosis. Muscle Nerve. 2005;29:707–715. doi: 10.1002/mus.20012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goding GS, Al-Sharif KI, McLoon L. Myonuclear addition to uninjured laryngeal myofibers in adult rats. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:552–557. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tucker HM. Human laryngeal reinnervation: long-term experience with the nerve-muscle pedicle technique. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:598–604. doi: 10.1002/lary.1978.88.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lexell J, Taylor CC, Sjostrom M. What is the cause of ageing atrophy? Total number, size and proportion of different fiber types studied in whole vastus lateralis muscle from 15- to 83- year old men. J Neurol Sci. 1988;84:275–94. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McComas AJ, Fawcett PR, Campbell MJ, Sica RE. Electrophysiological estimation of the number of motor units within human muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:121–31. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell MJ, McComas AJ, Petito F. Physiological changes in ageing muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36:174–82. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kadhiresan VA, Hassett CA, Faulkner JA. Properties of single motor units in medial gastrocnemius muscles of adult and old rats. J Physiol. 1996;93:543–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown MC, Holland RL, Hopkins WG. Motor nerve sprouting. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1981;4:17–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.04.030181.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodrigues AD, Schmalbruch H. Satellite cells and myonuclei in long-term denervated rat muscles. Anat Rec. 1995;243:430–437. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092430405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borisov AB, Carlson BM. Cell death in denervated skeletal muscle is distinct from classical apoptosis. Anat Rec. 2000;258:305–318. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000301)258:3<305::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McLoon KL, Wirtschafter JD. Activated satellite cells in extraocular muscles of normal adult monkeys and humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1927–1932. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]