Abstract

Objective

To assess factors associated with concomitant anal and cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in HIV-infected and at-risk women.

Design

A study nested within the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a multi-center longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in women conducted in six centers within the United States.

Methods

Four hundred and seventy HIV-infected and 185 HIV-uninfected WIHS participants were interviewed and examined with anal and cervical cytology testing. Exfoliated cervical and anal specimens were assessed for HPV using PCR and type-specific HPV testing. Women with abnormal cytologic results had colposcopy or anoscopy-guided biopsy of visible lesions. Logistic regression analyses were performed and odds ratios (ORs) measured the association for concomitant anal and cervical HPV infection.

Results

One hundred and sixty-three (42%) HIV-infected women had detectable anal and cervical HPV infection compared with 12 (8%) of the HIV-uninfected women (P <0.001). HIV-infected women were more likely to have the same human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype in the anus and cervix than HIV-uninfected women (18 vs. 3%, P <0.001). This was true for both oncogenic (9 vs. 2%, P = 0.003) and nononcogenic (12 vs. 1%, P <0.001) HPV types. In multivariable analysis, the strongest factor associated with both oncogenic and nononcogenic concomitant HPV infection was being HIV-infected (OR = 4.6 and OR = 16.9, respectively). In multivariable analysis of HIV-infected women, CD4+ cell count of less than 200 was the strongest factor associated with concomitant oncogenic (OR = 4.2) and nononcogenic (OR = 16.5) HPV infection.

Conclusion

HIV-infected women, particularly those women with low CD4+ cell counts, may be good candidates for HPV screening and monitoring for both cervical and anal disease

Keywords: anal intraepithelial neoplasia, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HIV-infection, human papillomavirus, women

Introduction

Infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) types in the anus or cervix can lead to invasive squamous cell carcinoma [1,2], and coinfection with HIV increases the risk for cancer at either site [3,4]. The increased risk of these cancers in HIV-infected individuals may be due to factors relating to HIV, such as HIV-induced immune dysfunction, as well as factors relating to HPV, such as longer persistence and increased replication of HPV [4,5]. Anogenital HPV infections are often multicentric and thus cervical HPV infection may serve as a reservoir and source of anal HPV infection or vice versa. Consistent with this, the risk of anal cancer is increased among women with a history of cervical cancer [6]. Several studies have assessed the relationship between anal and cervical HPV infections and intraepithelial neoplasia [anal intraepithelial lesions (AIN) and cervical intraepithelial lesions (CIN)] in HIV-infected women but few have included an HIV-uninfected comparison group, and few have included simultaneous assessment at both sites.

One of the first studies to assess CIN and AIN in HIV-uninfected women found that 19% of women with high-grade CIN also had concomitant AIN [7]. A subsequent study of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women injection drug users reported that anal HPV infection was twice as frequent as cervical HPV infection, and that HPV-associated epithelial abnormalities were associated with lower peripheral blood CD4+ cell counts [8]. Clinically, it is important to understand the risk of anal HPV infection and AIN among women with CIN and/or cervical HPV infection to optimize screening strategies in this population.

We previously reported on the prevalence of, and factors associated with, low-grade and high-grade AIN in a cohort study of women with and at risk for HIV infection [9]. We found the prevalence of AIN to be significantly increased among HIV-infected women (16%) compared with HIV-uninfected women (4%), even in the era of HAART. We also found that, after controlling for potential confounders, low-grade AIN was associated with different factors than high-grade AIN. In this investigation, we aimed to compare anal HPV infection and epithelial abnormalities with those of the cervix, and to assess the factors associated with concomitant anal and cervical HPV infection in a multisite cohort study of women with and at risk for HIV infection.

Methods

The work reported in this paper is the result of a study nested within the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a multicenter longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in women conducted in six centers within the United States. The methods and baseline cohort characteristics of the WIHS have been previously described [10]. To summarize, between October 1994 and November 1995, 2056 HIV-infected and 569 uninfected women were enrolled. A second period of enrollment occurred between October 2001 and September 2002, with the addition of 737 HIV-infected and 406 HIV-uninfected women. The HIV-infected women in the WIHS cohort reflect the ethnicity, exposure status, and ages of US women with AIDS [11].

Every 6 months, WIHS participants were interviewed using a structured questionnaire, had blood collected and received a physical examination. The physical examinations included a pelvic exam with cervical cytology testing using conventional smears and cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) fluid collection. Among HIV-infected women, blood collected at the study visit was tested for CD4+ lymphocytes and HIV RNA. With the aid of photo medication cards, interviewers collected data on self-reported antiretroviral therapy (ART) use during the period prior to the study visit.

Women were recruited for this WIHS anal sub-study during visits that occurred in years 2001–2003 at three of the WIHS sites: Brooklyn, Chicago, and San Francisco Bay Area [9]. Women were eligible if they had no history of high-grade AIN or anal cancer and all eligible women were asked to participate. In addition to the WIHS data and specimen collection, women enrolled in the anal sub-study were administered a short questionnaire containing questions specific to anal disease and received an external anal examination. Anal swab specimens were collected for centrally read anal cytology (ThinPrep) and anal HPV testing. After the results from the anal and cervical cytology testing were available, participants with abnormal results were contacted and asked to return for high resolution anoscopy (HRA) and/or colposcopy, as described previously [12]. Women enrolled in this sub-study were followed every 6 months, through April 2006. The data analyzed in this article are from the baseline visit of the anal sub-study. Consent materials were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at each of the collaborating institutions and informed written consent was obtained from the participants.

As previously described, exfoliated cells for HPV DNA testing were obtained using CVL and anal swabs [13,14]. HPV DNA was detected with L1 consensus primer MY09/MY11/HMB01 polymerase chain reaction assays. Details of these laboratory methods have been published previously [15], and the results were shown to have high reproducibility, sensitivity and specificity [14,16,17]. Amplification products were probed for the presence of any HPV DNA with a generic probe mixture and probed for HPV DNA with filters individually hybridized with type-specific biotinylated oligonucleotide probes [15,16].

Anal and cervical cytology results were categorized according to the Bethesda system: negative for squamous intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (negative); atypical squamous cells (ASC); low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL); and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) [18]. Women with unsatisfactory cervical or anal cytology, primarily due to insufficient cellularity, were excluded from cytology classification. Anal and cervical histological results were categorized as benign, atypia, condyloma, AIN 1/CIN1, and AIN 2+/CIN 2+. For this analysis, we defined the grade of the lesion as the more advanced diagnosis on cytology or histology when both were available. In the absence of histological data, grade was based on cytology alone. We hereafter refer to this combined categorization as ‘cytology/histology’.

HPV infection was categorized several different ways for our analyses, based on the HPV types and number of HPV types that were detected. HPV genotypes were probed for individually and then grouped into oncogenic HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) and nononcogenic types (6, 11, 26, 32, 40, 53, 54, 55, 61, 66, 70, 73, 82, 83, 84), a mixture of 10 additional but rare HPV types (probe mix), and ‘positive but unknown type’ (HPV types that hybridized only with the consensus probe) [19].

Contingency table analyses were performed to compare participant characteristics by anal and cervical HPV genotypes by HIV serostatus, CD4 cell count category, or history of anal intercourse; two-tailed P-values were based on chi-square or Fisher exact tests. The Pearson and weighted κ statistics were used to measure the correlation and agreement between anal and cervical cytology/histology. Logistic regression analyses were done to compute unadjusted odds ratios (OR, hereafter referred to as risk), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and P-values to estimate the relationship between each factor and the occurrence of concomitant anal and cervical oncogenic (defined as having one or more of the same oncogenic HPV type(s) in both the anus and cervix) and nononcogenic (defined as having one or more of the same nononcogenic HPV type(s) in both the anus and cervix) HPV infection. For the regression analyses, women without concomitant oncogenic or nononcogenic HPV infection were the reference groups. We then performed multivariable logistic regression analysis, including those characteristics that were associated (P <0.1) with either concomitant oncogenic or nononcogenic HPV infection in the unadjusted analyses. All multivariable models also included those variables that have been previously reported to be associated with HPV infection, regardless of their statistical significance in our data set. These included HIV status, age, and cigarette smoking status. For models restricted to HIV-infected women, we included HAART use, HIV RNA level, and CD4+ cell count. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Due to missing data for some study variables, the sample size varied for each analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 [20].

Results

Four hundred and seventy (72%) HIV-infected and 185 (28%) HIV-uninfected women were enrolled in the anal sub-study. Approximately one-third of the sample was recruited from each of the three WIHS sites and among the 655 anal sub-study participants, 67% of the women were 31–50 years of age, 69% were non-Hispanic Black, 34% had a greater than high school education, 29% were married or living with a partner, 53% had a household income of $12,000 or less, 55% were current cigarette smokers, 52% were abstainers from alcohol, 32% had ever injected drugs, and 47% reported ever having anal intercourse.

A total of 163 HIV-infected women (42%) had detectable anal and cervical HPV infection compared with 12 HIV-uninfected women (8%, P <0.001). HIV-infected women with both anal and cervical HPV infection had a higher mean number of years smoking cigarettes (mean = 15.7 years) than those without detectable anal and cervical HPV infection (mean = 12.8 years, P = 0.02). There was no difference in the mean number of lifetime anal sex partners; mean = 2.1 partners for women with both anal and cervical HPV infection and mean = 2.2 partners for women without detectable anal and cervical HPV infection (P = 0.66). Among HIV-uninfected women, those with both anal and cervical HPV infection had a nonsignificantly lower mean number of years smoking cigarettes (mean = 7.9 years) and mean number of lifetime anal sex partners (mean = 1.5 partners) than those without detectable anal and cervical HPV infection (mean = 10.7 years smoking, P = 0.41 and mean 2.5 partners, P = 0.09, respectively).

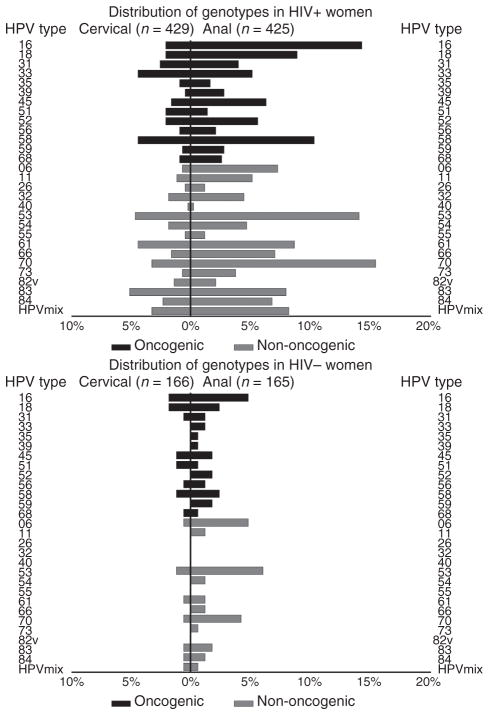

Overall, the detection rates of both cervical and anal HPV genotypes were more frequent in HIV-infected women than HIV-uninfected women (Fig. 1). Compared with HIV-uninfected women, HIV-infected women were significantly more likely to have cervical infection with HPV types 33, 53, 58, 61, 70, 83 and the HPV mix. HIV-infected women were also more likely than HIV-uninfected women to have anal infection with HPV types 11, 16, 18, 31, 32, 33, 45, 52, 53, 54, 58, 61, 66, 70, 73, 83, 84, and HPV mix. When the analyses of the HPV genotypes were restricted to women without a reported history of anal sex, the overall HPV DNA detection remained more frequent in the anus than the cervix.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of cervical and anal human papilloma-virus (HPV) genotypes (percentage detected) among the women from the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, and Brooklyn Women’s Interagency HIV Study, stratified by HIV serostatus.

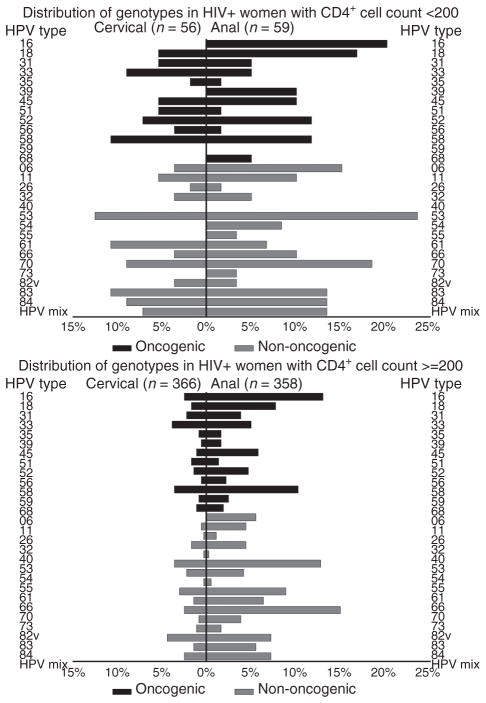

When the distribution of HPV genotypes for HIV-infected women were stratified on current CD4+ cell counts, compared with women with CD4+ cell count of at least 200, women with CD4+ cell counts of less than 200 were significantly more likely to have cervical infection with HPV types 6,11, 52, 53, 58, 61, 70, 83, and 84 (Fig. 2). HIV-infected women with CD4+ cell counts of less than 200 were also significantly more likely than women with CD4+ cell counts of at least 200 to have an anal infection with HPV types 6, 18, 39, 52, 53, 84, and HPV mix.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of cervical and anal human papilloma-virus (HPV) genotypes (percentage detected) among the HIV-infected women from the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, and Brooklyn Women’s Interagency HIV Study, stratified by CD4+ cell count group (<200 vs. ≥200).

HIV-infected women were more likely to have the same HPV genotype in the anus and cervix (concomitant HPV infection) than HIV-uninfected women, 68 (18%) vs. four (3%); P <0.001. This was true for both oncogenic, 33 (9%) vs. three (2%) P = 0.003, and nononcogenic, 47 (12%) vs. one (1%); P <0.001, HPV types. HIV-infected women were also more likely to have concomitant HPV infection with more than one HPV type (19 women) compared with HIV-uninfected women (0 women).

Analyses for risk of concomitant anal and cervical oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV infection among all women are shown in Table 1. In analysis adjusted for age and cigarette smoking, women with HIV infection (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.4–15.5) were more likely to have concomitant anal and cervical oncogenic HPV infection than HIV-uninfected women. In analysis adjusted for age, employment and cigarette smoking, women with HIV infection (OR 16.9, 95% CI 2.3–125), a history of anal sex (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.0), and nondrinkers of alcohol (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1–4.3) were more likely to have concomitant nononcogenic HPV infection than HIV-uninfected women, those with no history of anal sex, and consumers of alcohol, respectively.

Table 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for key study variables and their association with concomitant anal and cervical human papillomavirusa infection among the 536 women from the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, and Brooklyn Women’s Interagency HIV Study.b

| Variable | Concomitant oncogenic HPV (n = 36)

|

Concomitant nononcogenic HPV (n = 48)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted

|

Adjustedc

|

Unadjusted

|

Adjustedd

|

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| HIV status | ||||||||

| HIV-uninfected | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| HIV-infected | 4.6 | 1.4–15.2 | 4.6 | 1.4–15.5 | 20.6 | 2.8–151 | 16.9 | 2.3–125 |

| Age, 10-year groups | 1.1 | 0.79–1.6 | 0.96 | 0.66–1.4 | 1.2 | 0.87–1.6 | 1.0 | 0.71–1.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.5 | 0.62–3.6 | 0.71 | 0.27–1.9 | ||||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.74 | 0.10–5.7 | 1.1 | 0.24–4.8 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | 0.35–3.1 | 1.3 | 0.55–3.1 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||

| Unemployed | 1.6 | 0.74–3.5 | 2.8 | 1.3–6.2 | 2.1 | 0.93–4.8 | ||

| History of receptive anal intercourse | ||||||||

| Never had receptive anal intercourse | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||

| Ever had receptive anal intercourse | 1.4 | 0.71–2.7 | 1.8 | 0.98–3.3 | 2.1 | 1.1–4.0 | ||

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||

| Never or former smoker | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| Current smoker | 1.6 | 0.79–3.2 | 1.5 | 0.76–3.1 | 1.4 | 0.75–2.5 | 1.2 | 0.65–2.4 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||

| Currently drinks alcohol | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||

| No current alcohol use | 1.3 | 0.68–2.7 | 2.2 | 1.2–4.2 | 2.2 | 1.1–4.3 | ||

| History of injection drug use | ||||||||

| Never injected drugs | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Ever injected drugs | 1.1 | 0.54–2.3 | 1.5 | 0.81–2.7 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; OR, odds ratio.

Having one or more of the same HPV type(s) in both the anus and the cervix.

Women without concomitant anal and cervical HPV infection are the reference group. Only women with complete data on all study variables were included in the multivariate analyses.

Adjusted for HIV infection, age, and smoking status.

Adjusted for HIV infection, age, employment, history of anal sex, smoking status, and alcohol use.

Among the HIV-infected women in analysis adjusted for age, cigarette smoking, HAART use, and viral load, only lower CD4+ cell count (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.4–12.3 for CD4+ <200; OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.49–3.0 for CD4+ 200–500; referent CD4+ >500) was significantly associated with concomitant oncogenic HPV infection (Table 2). In analysis of concomitant nononcogenic HPV infection and adjusting for age, cigarette smoking, alcohol and HAARTuse, and HIV RNA, only CD4+cell count (OR 16.5, 95% CI 4.8–56.4 for CD4+<200; OR 5.1, 95% CI 1.7–15.6 for CD4+ 200–500; referent CD4+ >500) remained significant.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for key study variables and their association with concomitant anal and cervical HPVa infection among the 386 HIV-infected women from the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, and Brooklyn Women’s Interagency HIV Study.b

| Variable | Concomitant oncogenic HPV (n = 33)

|

Concomitant nononcogenic HPV (n = 44)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted

|

Adjustedc

|

Unadjusted

|

Adjustedc

|

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age, 10-year groups | 0.90 | 0.61–1.3 | 0.78 | 0.51–1.2 | 1.0 | 0.74–1.4 | 0.99 | 0.66–1.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.9 | 0.77–4.7 | 0.63 | 0.21–1.9 | ||||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.97 | 0.12–7.8 | 1.3 | 0.28–6.2 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.86 | 0.25–3.0 | 1.4 | 0.56–3.3 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.9 | 0.74–4.6 | 2.1 | 0.93–4.6 | ||||

| History of receptive anal intercourse | ||||||||

| Never had receptive anal intercourse | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Ever had receptive anal intercourse | 1.3 | 0.64–2.7 | 1.7 | 0.94–3.2 | ||||

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||

| Never or former smoker | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| Current smoker | 1.7 | 0.81–3.6 | 1.8 | 0.81–3.9 | 1.4 | 0.74–2.6 | 1.2 | 0.56–2.4 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||

| Currently drinks alcohol | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||

| No current alcohol use | 1.3 | 0.62–2.7 | 2.1 | 1.1–4.1 | 1.9 | 0.92–4.0 | ||

| History of injection drug use | ||||||||

| Never injected drugs | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | ||||

| Ever injected drugs | 1.1 | 0.52–2.3 | 1.3 | 0.72–2.5 | ||||

| Current HAART use | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| Yes | 2.3 | 1.1–5.1 | 2.3 | 0.99–5.5 | 1.8 | 0.96–3.4 | 1.7 | 0.80–3.8 |

| CD4+ cell count μl | ||||||||

| >500 | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| 200–500 | 1.3 | 0.53–3.1 | 1.2 | 0.49–3.0 | 5.3 | 1.8–15.8 | 5.1 | 1.7–15.6 |

| <200 | 4.0 | 1.6–10.4 | 4.2 | 1.4–12.3 | 18.4 | 5.9–57.6 | 16.5 | 4.8–56.4 |

| HIV RNA, copies | ||||||||

| <500 | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 | Referent |

| 500–10 000 | 1.3 | 0.56–2.9 | 1.4 | 0.55–3.5 | 1.1 | 0.52–2.5 | 0.93 | 0.37–2.3 |

| >10 000 | 0.90 | 0.36–2.2 | 0.70 | 0.24–2.1 | 1.8 | 0.89–3.7 | 1.1 | 0.43–2.7 |

CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus; OR, odds ratio.

Having one or more of the same HPV type(s) in both the anus and the cervix.

Women without concomitant anal and cervical HPV infection are the reference group. Only women with complete data on all study variables were included in the multivariate analyses.

Adjusted for age, employment, smoking status, HAART use, CD4+ cell count, and HIV RNA.

Among the 394 HIV-infected and 160 HIV uninfected women with adequate anal and cervical cytologic/histologic samples, there was little correlation between severity of anal and cervical disease (Table 3). When including only those women with no disease and those with low-or high-grade disease (excluding women with ASCUS/atypia), the Pearson correlation between anal and cervical disease was 0.21 (95% CI 0.09–0.34) for the 307 HIV-infected women and 0.26 (95% CI–0.06–0.58) for the 139 HIV-uninfected women. When restricted to only HIV-infected women with concomitant oncogenic or nononcogenic HPV types (the sample size was not sufficient for separate analyses of the HIV-uninfected women), the Pearson correlation between anal and cervical disease remained low and was 0.21 (95% CI–0.13–0.54) for concomitant oncogenic types and 0.11 (95% CI–0.18–0.40) for concomitant nononcogenic types.

Table 3.

Anal and cervical cytology/histology among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women from the San Francisco Bay Area, Chicago, and Brooklyn WIHS.

| Anal cytology/histologya | Cervical cytology/histologya

|

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative/benign | ASC/Atypia | LSIL/condyloma/CIN1 | HSIL+/CIN2+ | ||

| HIV-infected women | |||||

| Negative/benign | 196 | 35 | 29 | 14 | 274 |

| ASC/Atypia | 25 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 40 |

| LSIL/Condyloma/AIN1 | 23 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 50 |

| HSIL/AIN2+ | 16 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 30 |

| Total | 260 | 48 | 63 | 23 | 394 |

| Pearson correlation 0.191, 95% CI 0.080–0.302 Weighted κ 0.160, 95% CI 0.074–0.247 |

|||||

| HIV-uninfected women | |||||

| Negative/Benign | 120 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 146 |

| ASC/Atypia | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| LSIL/Condyloma/AIN1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| HSIL/AIN2+ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 129 | 17 | 11 | 3 | 160 |

| Pearson correlation 0.242, 95% CI 30.048 to 0.531 Weighted κ 0.180, 95% CI 30.033 to 0.393 |

|||||

AIN, anal intraepithelial lesions; ASC, atypical squamous cells; CIN, cervical intraepithelial lesions; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Tests for equal κ coefficients, controlling for HIV status, weighted κ chi-square = 0.163 P-value = 0.87.

The grade of the lesion was defined as the more advanced diagnosis on cytology or histology when both were available. In the absence of histological data, grade was based on cytology alone.

Discussion

Our findings show that HIV-infected women were more likely than HIV-uninfected women to have concomitant anal and cervical HPV infection. Although other smaller studies have found rates of concomitant infection and neoplasia to be higher in HIV-infected women than HIV-uninfected women [8,12,21,22], to our knowledge this is one of the largest studies to report results from both anatomical sites combined and to include an HIV-uninfected comparison group.

Both oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV types were more prevalent in the anus than in the cervix. In particular, the prevalence of HPV 16 in the anus was fourfold greater than HPV 16 in the cervix and HPV 18 was three-fold greater in the anus than in the cervix. This has important implications regarding the risk of anal cancer, potential for spread to the cervix, and the potential benefit of vaccination against HPV types 16 and 18 before sexual debut [23–28].

Among HIV-infected women, those with lower CD4+ cell counts were more likely to have detectable oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV types in both the cervix and anus than women with CD4+ counts of at least 200 cells/μl. This may be because of higher levels of HPV replication in women with compromised immune systems and consequently an increased risk of spread between the two anatomic sites. In this subset of WIHS women we again noted that in the cervix, there was an inverse relationship between lower CD4 levels and higher prevalence of most HPV types but not HPV 16 [29]. This observation has led to the suggestion that HPV 16 is not subject to the same level of immune control as other HPV types, perhaps contributing to its greater oncogenicity than other HPV types. Notably, we did not observe this in the anal canal, wherein the relationship between HPV 16 prevalence and lower CD4 level appeared to be the same as for other HPV types. These data suggest that HPV 16 may be subjected to different immune control in the anus and the cervix.

Among all the women in the study, we found that HIV-infected women had a greater than four-fold increased risk for having concomitant oncogenic HPV infection and a greater than 16-fold increased risk for having concomitant nononcogenic HPV infection than uninfected women. Among the HIV-infected women, lower CD4+ cell count was associated with a greater risk of concomitant oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV infection, similar to what has been reported among women in the WIHS when looking separately at the risk of cervical and anal HPV [30,31]. Due to the size of the study and the relatively high prevalence of HPV infection, this is one of the first studies to analyze risk factors for concomitant oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV infection separately.

In analyses of all women, we found an association between a history of receptive anal intercourse and a greater than two-fold risk of concomitant nononcogenic HPV infection. Perhaps due to smaller numbers, the relationship between anal intercourse and concomitant oncogenic HPV infection did not reach statistical significance: this was also true when the analyses were restricted to only the HIV-infected women. However, we also found the prevalence of HPV genotypes was higher in the anus than in the cervix even among women with no reported history of anal sex. The association between history of anal sex and anal HPV infection in women has not been consistently reported [22,32,33]. This may be because receptive anal intercourse is not necessary to acquire anal HPV infection and in women HPV transmission may occur from the cervicovaginal compartment to the anal mucosa [34].

Unexpectedly, our result showed that nondrinkers of alcohol had an increased risk of concomitant nononcogenic HPV infection. This observation may be the result of unmeasured confounding rather than a causal association between alcohol consumption and a reduced risk of concomitant HPV infection.

When measured at a single time point and using both cytology and histology, there was little correlation between grade of anal and cervical intraepithelial abnormalities in the HIV-infected and uninfected women. This confirms what others have reported using cytology only [32,33] and is to be expected given the heterogeneity of HPV types at the two anatomic sites. This may reflect the HPV types that are present or persist in the two anatomical sites and differences in biological behavior and host immune response at the two sites.

This study had several limitations. The analysis was cross-sectional, and likely underestimated the true prevalence of cervical and anal disease by only performing colposcopy or HRA on women with abnormal cervical or anal cytology, respectively. Although our study comprises one of the largest groups of HIV-infected women to be analyzed for concomitant anal and cervical HPV-related disease and infection, some of the subgroup analyses were limited by small sample sizes.

Unquestionably, the use of HAART to treat HIV infection and AIDS has led to a dramatic reduction in HIV-related morbidity and mortality resulting in HIV-infected individuals reaching ages in which cancer incidence rapidly increases. The combination of older age, extended duration of immunosuppression, and a longer latency period for oncogenic viruses such as HPV may put women with HIV/AIDS at an increased risk of malignancies, including anal and cervical cancers. In our study, HAART use was not associated with a decreased risk of concomitant oncogenic or nononcogenic HPV infection. We found that HIV-infected women were more likely than HIV-uninfected women to have concomitant oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV infection. Lower CD4+ cell count was associated with a greater prevalence of HPV genotypes and risk of concomitant oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV infection. To prevent the development of HPV-related neoplasia, HIV-infected women, especially those women with low CD4+ cell counts, may be good candidates for HPV screening and monitoring for both HPV-related cervical and anal disease.

Acknowledgments

The National Cancer Institute provided primary funding for this study–R01 CA 88739, Principal Investigator Joel Palefsky, and R01 CA 85178, Principal Investigator Howard Strickler. Additional data in this article were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Cytyc Corporation provided the ThinPrep anal cytology materials to the study.

We are deeply grateful to the women who consented to be part of this study. We also would like to acknowledge Ginger Carey and Helen Carey for their help with data cleaning and Niloufar Ameli for her help producing the figures.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 88739 and R01 CA 85178), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632), the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS funded by the NIH (AI-51519) and the Einstein Cancer Research Center (P30CA013330) from the National Cancer Institute. Funding also is provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131).

Footnotes

N.A.H. contributed to the design of the project, led the statistical analyses and interpretation of results, and writing of the article. E.A.H. helped to conceive of the study design and contributed to the data analyses and writing of the article. J.T.E. contributed to the data management and statistical analyses, and writing of the article. H.M. contributed to the design and execution of the project and writing of the article. K.W. contributed to the execution of the project and writing of the article. T.M.D. contributed to the design of the project, read all the anal cytology and histology specimens, and contributed to the writing of the article. R. D.B. contributed to the design of the project, the HPV genotyping, and writing of the article. H.D.S. contributed to the design of the project, HPV genotyping, interpretation of results, and writing of the article. R.M.G. contributed to the design and execution of the project and writing of the article. J.M.P. was the lead investigator of this project, conceived of the study design, and contributed to the HPV genotyping, analyses, interpretation of results, and writing of the article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

An earlier version of this study was presented at the 24th International Papillomavirus Conference and Clinical Workshop, Beijing, China, 3–9 November, 2007.

References

- 1.Melbye M, Sprogel P. Aetiological parallel between anal cancer and cervical cancer. Lancet. 1991;338:657–659. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91233-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zbar AP, Fenger C, Efron J, Beer-Gabel M, Wexner SD. The pathology and molecular biology of anal intraepithelial neoplasia: comparisons with cervical and vulvar intraepithelial carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00384-001-0369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagensee ME, Cameron JE, Leigh JE, Clark RA. Human papillomavirus infection and disease in HIV-infected individuals. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:57–63. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madkan VK, Cook-Norris RH, Steadman MC, Arora A, Mendoza N, Tyring SK. The oncogenic potential of human papillomaviruses: a review on the role of host genetics and environmental cofactors. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:228–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin F, Bower M. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV positive people. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:327–331. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.5.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemminki K, Dong C, Vaittinen P. Second primary cancer after in situ and invasive cervical cancer. Epidemiology. 2000;11:457–461. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholefield JH, Hickson WG, Smith JH, Rogers K, Sharp F. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: part of a multifocal disease process. Lancet. 1992;340:1271–1273. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92961-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams AB, Darragh TM, Vranizan K, Ochia C, Moss AR, Palefsky JM. Anal and cervical human papillomavirus infection and risk of anal and cervical epithelial abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessol NA, Holly EA, Efird JT, Minkoff H, Schowalter K, Darragh TM, et al. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in a multisite study of HIV-infected and high-risk HIV-uninfected women. AIDS. 2009;23:59–70. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831cc101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holly EA, Ralston ML, Darragh TM, Greenblatt RM, Jay N, Palefsky JM. Prevalence and risk factors for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:843–849. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Jay N. Prevalence and risk factors for human papillomavirus infection of the anal canal in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:361–367. doi: 10.1086/514194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palefsky JM, Minkoff H, Kalish LA, Levine A, Sacks HS, Garcia P, et al. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:226– 236. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burk RD, Ho GY, Beardsley L, Lempa M, Peters M, Bierman R. Sexual behavior and partner characteristics are the predominant risk factors for genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:679–689. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu W, Jiang G, Cruz Y, Chang CJ, Ho GY, Klein RS, et al. PCR detection of human papillomavirus: comparison between MY09/MY11 and GP5+/GP6+primer systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1304–1310. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1304-1310.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang G, Qu W, Ruan H, Burk RD. Elimination of false-positive signals in enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection of amplified HPV DNA from clinical samples. Biotechniques. 1995;19:566–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. A review of human carcinogens: Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–322. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT user’s guide. Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc; 2010. Version 9.3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melbye M, Smith E, Wohlfahrt J, Osterlind A, Orholm M, Bergmann OJ, et al. Anal and cervical abnormality in women: prediction by human papillomavirus tests. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:559–564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961127)68:5<559::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Da Costa M, Greenblatt RM. Prevalence and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:383–391. doi: 10.1086/318071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villa LL. Overview of the clinical development and results of a quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) vaccine. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11 (Suppl 2):S17–S25. doi: 10.1016/S1201-9712(07)60017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez G, Lazcano-Ponce E, Hernandez-Avila M, Garcia PJ, Munoz N, Villa LL, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine in Latin American women. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1311–1318. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa L, Nolan T, Marchant C, Radley D, et al. Impact of baseline covariates on the immunogenicity of a quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) human papillomavirus virus-like-particle vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1153–1162. doi: 10.1086/521679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson SE, Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Malm C, et al. Induction of immune memory following administration of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine. Vaccine. 2007;25:4931–4939. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, Iversen OE, et al. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1459–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villa LL, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, et al. Immunologic responses following administration of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus Types 6, 11, 16, and 18. Vaccine. 2006;24:5571–5583. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strickler HD, Palefsky JM, Shah KV, Anastos K, Klein RS, Minkoff H, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and immune status in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1062–1071. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palefsky J. Human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected persons. Top HIV Med. 2007;15:130–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Massad LS, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park IU, Ogilvie JW, Jr, Anderson KE, Li ZZ, Darrah L, Madoff R, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and abnormal anal cytology in women with genital neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kojic EM, Cu-Uvin S, Conley L, Bush T, Onyekwuluje J, Swan DC, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cytologic abnormalities of the anus and cervix among HIV-infected women in the study to understand the natural history of HIV/AIDS in the era of effective therapy (the SUN study) Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:253–259. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f70253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgren G, Sparen P. Risk of anogenital cancer after diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a prospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:311–316. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]