Abstract

To explore the role of axon guidance molecules during regeneration in the lamprey spinal cord, we examined the expression of mRNAs for semaphorin 3 (Sema3), semaphorin 4 (Sema4), and netrin during regeneration by in situ hybridization. Control lampreys contained netrin-expressing neurons along the length of the spinal cord. After spinal transection, netrin expression was downregulated in neurons close (500 μm to 10 mm) to the transection at 2 and 4 weeks. A high level of Sema4 expression was found in the neurons of the gray matter and occasionally in the dorsal and the edge cells. Fourteen days after spinal cord transection Sema4 mRNA expression was absent from dorsal and edge cells but was still present in neurons of the gray matter. At 30 days the expression had declined to some extent in neurons and was absent in dorsal and edge cells. In control animals, Sema3 was expressed in neurons of the gray matter and in dorsal and edge cells. Two weeks after transection, Sema3 expression was upregulated near the lesion, but absent in dorsal cells. By 4 weeks a few neurons expressed Sema3 at 20 mm caudal to the transection but no expression was detected 1 mm from the transection. Isolectin I-B4 labeling for microglia/macrophages showed that the number of Sema3-expressing microglia/macrophages increased dramatically at the injury site over time. The downregulation of netrin and upregulation of Sema3 near the transection suggests a possible role of netrin and semaphorins in restricting axonal regeneration in the injured spinal cord.

Indexing terms: axonal guidance, spinal cord regeneration, in situ hybridization, semaphorins, netrin

Axons in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) do not regenerate spontaneously following injury and consequently there is little functional recovery. This differs from the response of lampreys, which show regeneration of axons and functional recovery after complete spinal transection, despite Wallerian degeneration (Rovainen, 1976; Selzer, 1978; Wood and Cohen, 1979). The regeneration is directionally specific (Mackler et al., 1986; Yin et al., 1984), results in synapse formation selectively with normal types of target neurons distal to the lesion (Mackler and Selzer, 1987), and involves functional reconnection of central pattern generators on opposite sides of the lesion (Cohen et al., 1988). The specificity of axonal regeneration might suggest involvement of axonal guidance molecules, similar to their involvement in axonal growth during development. Research conducted during the last decade has identified several discrete classes of diffusible and transmembrane proteins that act as attractant and repellent cues in guiding axonal growth during development. Among them are the netrins, semaphorins, ephrins, and slits (reviewed in Moore and Kennedy, 2006).

The first diffusible attractants to be identified, the netrins, comprise a small family of laminin-related secreted proteins of ≈600 amino acids, with multifunctional roles in axon guidance (Kennedy et al., 1994; Serafini et al., 1994; Manitt and Kennedy, 2002). Roles for netrins and their receptors in axon guidance are conserved across species, ranging from Caenorhabditis elegans to Homo sapiens. Netrins can be either attractants or repellents, depending on the receptors with which they interact. Attractive effects are mediated by receptors that incorporate members of the Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) subfamily of the Ig superfamily (Keino-Masu et al., 1996). The repellent effects of netrins appear to be mediated by homologs of UNC-5, a receptor that mediates repulsive actions of the netrin UNC-6 in C. elegans (Hamelin et al., 1993). Homologs of UNC-5 have been found in mammals (Leonardo et al., 1997). In vivo, Netrin-1 and DCC play important roles in retinal ganglion cell axon pathfinding (Deiner et al., 1997) and the formation of corpus callosum, hippocampal commissures, and thalamocortical projections (Serafini et al., 1996; Fazeli et al., 1997; Braisted et al., 2000). In cultured Xenopus neurons, direct interactions between the intracellular domains of DCC and UNC-5 converted the chemoattractive effect of Netrin-1 to repulsion (Hong et al., 1999). It was concluded that the long-range chemorepulsive effects of netrin are mediated by a receptor complex combining DCC and UNC-5, while short-range repulsive effects are mediated by UNC-5 homodimers (or heterodimers with a still unknown co-receptor) (Keleman and Dickson, 2001; Brankatschk and Dickson, 2006). The response to a Netrin-1 gradient also depends on the activities of intracellular cyclic nucleotides. Xenopus neurons are attracted to a gradient of Netrin-1 and repulsed by the same gradient when intracellular cAMP activity is blocked with a competitive cAMP analog or by Protein Kinase A inhibitors (Ming et al., 1997).

With at least 30 members, the semaphorins make up the largest family of axon guidance cues yet described (Raper, 2000; Fiore and Puschel, 2003). Semaphorins are defined by a conserved ≈500-amino acid extracellular semaphorin domain (Kolodkin et al., 1993). Semaphorins are divided into eight classes, of which Classes 3–7 are found in vertebrates. Class 3 semaphorins are secreted, Classes 4–6 are transmembrane proteins, and Class 7 are membrane-associated via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage (Semaphorin Nomenclature Committee, 1999). They are classically described as collapsing factors and mediators of axon repulsion in vitro (Luo et al., 1993) and in vivo (Kolodkin et al., 1992) as factors that regulate fasciculation (Taniguchi et al., 1997) and exclude axons from inappropriate regions of the nervous system during development (Kitsukawa et al., 1997; Taniguchi et al., 1997). However, they may act as context-dependent chemoattractants as well (Wong et al., 1997, 1999; Bagnard et al., 1998; de Castro et al., 1999; Masuda et al., 2004; Schwamborn et al., 2004). Multiple receptors or receptor complexes mediate semaphorin signaling. Neuropilin (Npn)-1 and -2 are transmembrane proteins that bind the Class 3 semaphorins and are necessary for semaphorin signaling (Chen et al., 1997; Feiner et al., 1997; He and Tessier-Lavigne, 1997; Giger et al., 1998b). Npns comprise only part of a receptor complex (Nakamura et al., 1998), requiring co-receptors, including the Plexins and Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM)-L1. Plexins-A through -D bind certain semaphorin classes directly, and can act as co-receptors with Npns in mediating Class 3 semaphorin effects (Winberg et al., 1998; Tamagnone et al., 1999; Castellani and Rougon, 2002).

Involvement of netrins and semaphorins in attracting and repelling growth cones during embryonic development have been reviewed extensively (Culotti and Kolodkin, 1996; Goodman, 1996; Kolodkin, 1998; Raper, 2000) and recent experimental data suggested that semaphorins may be involved in restricting the ability of spinal cord axons to regenerate after injury (Pasterkamp et al., 1998a–c, 1999; Pasterkamp and Verhaagen, 2001; De Winter et al., 2002; Moreau-Fauvarque et al., 2003; Hashimoto et al., 2004).

To gain new insights into the function of axon guidance molecules in axonal regeneration, we studied the lamprey spinal cord. This can be studied by wholemount in situ hybridization (Swain et al., 1994), due in part to the flat shape of the cord and to the lack of myelin (Bullock et al., 1984), which makes the entire central nervous system (CNS) translucent.

As a first step in determining the molecular mechanisms involved in guiding and modulating axonal regeneration in the injured spinal cord, we cloned lamprey Sema3, Sema4, and netrin and determined their expression patterns in the spinal cord by in situ hybridization (Shifman and Selzer, 2000a,b, 2006).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Wildtype larval lampreys (Petromyzon marinus), 12–14 cm in length (4–5 years old) and in a stable stage of neurological development, were obtained from streams feeding lake Michigan and maintained in freshwater tanks at 16°C until the day of surgery.

Spinal cord transection

Animals were anesthetized by immersion in 0.1% tricaine methanesulfonate and the spinal cords exposed from the dorsal midline at the level of the fifth gill. Transection of the spinal cord was performed with Castroviejo scissors, after which the wound was allowed to air-dry over ice for 1 hour. Each transected animal was examined 24 hours after surgery to confirm that there was no movement caudal to the lesion site. A transection was tentatively considered complete if on stimulation of the head an animal could move only its head and body rostral to the lesion. Animals were allowed to recover in freshwater tanks at room temperature. At the specified recovery times, animals were reanesthetized and the spinal cords and brains were removed for in situ hybridization. Experiments were carried out on 65 large larval lampreys that were either untransected (n = 10) or permitted to recover 2 weeks (n = 20), 4 weeks (n = 20), or 5 months (n = 15). Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania.

Riboprobe synthesis

Previously cloned cDNAs for netrin (Shifman and Selzer, 2000a) and lamprey Sema3 and Sema4 (Shifman and Selzer, 2006) were used as templates for the generation of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled sense and antisense riboprobes for in situ hybridization on spinal cord paraffin sections and wholemount preparations of control and spinal-transected animals.

Probes were made from the same templates used to make cDNA for sequences and phylogenetics analysis (Shifman and Selzer, 2006). The netrin cRNA probe was transcribed from a 221-bp fragment spanning LamNT (Laminin N-terminal domain VI) domain of netrin (nucleotides 1–221; GenBank access. no. DQ888320; Shifman and Selzer, 2000b). The Sema3 probe was transcribed from a 718-bp sequence spanning semaphorin domain (nucleotides 1–718; GenBank access. no. AY744920; Shifman and Selzer, 2006) and Sema4 probe was transcribed from a 906-bp sequence spanning semaphorin and PSI domains (nucleotides 1–906; GenBank access. no. AY744921; Shifman and Selzer, 2006). Lamprey netrin, Sema3, and Sema4 cDNAs cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) were linearized with restriction enzymes and gel-purified. The DIG incorporation into probes was controlled by dot blots. The length and integrity of the probes was examined by gel electrophoresis. Sense RNA probes were used as controls. We should emphasize that only one gene for each of the lamprey semaphorins was found (Shifman and Selzer, 2006) and lamprey Sema3 and Sema4 represent precursor genes existing prior to the origin of Sema3A–G and Sema4A–G subfamilies.

Wholemount in situ hybridization

Wholemount preparations increase the amount of information gathered per experiment and preserve 3D information, which allows for the rapid and accurate identification of labeled cells. Hybridization of DIG-labeled riboprobes to wholemounted lamprey spinal cord was performed using a method developed by us and optimized for the lamprey (Shifman and Selzer, 2000b). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibody was diluted 1:1,000 in maleic buffer and applied to the tissue for 48 hours at 4°C. The tissue was washed in fresh changes of maleic buffer followed by fresh changes of SMT (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 0.1% Tween 20, 5 mM Levamisole) and reacted with nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP) chromogen substrate (Roche, Nutley, NJ) for 30–60 minutes until a blue reaction product was clearly visible. The spinal cord was washed in PBS, cleared in cedarwood oil, and mounted in Permount for microscopy. DIG-labeled sense RNA probes were used as internal controls and did not produce hybridization signals (Fig. 1L,M). Images were captured digitally using an AxioCam CCD Video Camera (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) attached to a Zeiss Axioskop microscope with AxioVision software and scale bars were added. Images were imported into Adobe Photoshop 7 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The images were cropped and adjusted for brightness and contrast and labels were added.

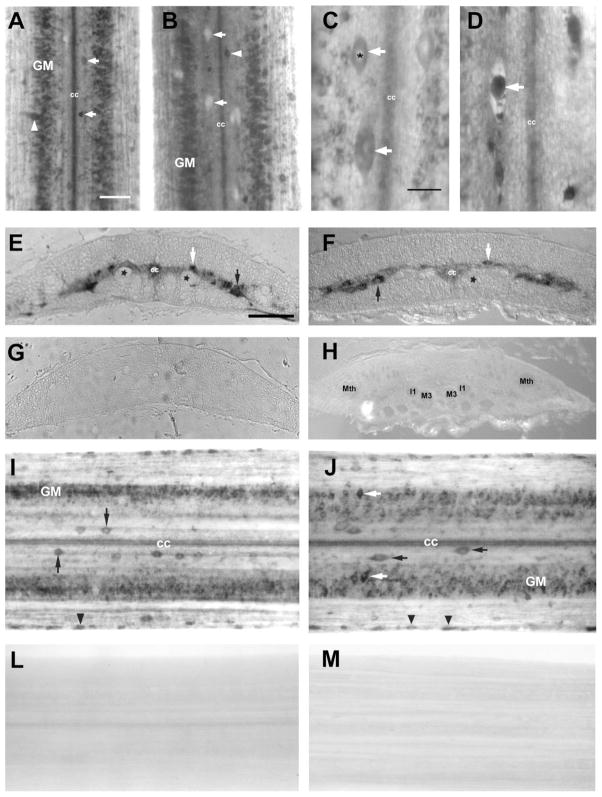

Fig. 1.

The gross cytoarchitecture of the lamprey spinal cord after transection. Photomicrographs obtained at 30 days postinjury showing the spinal cord: control (A) and transected (B). The gross cytoarchitecture of the spinal cord caudal to the lesion site remained largely intact and spinal “gray matter” could be discerned clearly in whole-mounts that were stained with Toluidine blue. Most neuronal and glial cell bodies are located in the central “gray matter” (GM) with axon tracts surrounding them (A,B). Dorsal cells are identified with white arrows and lateral cells with white arrowhead (A). Note lack of Nissl staining in dorsal cells (B, white arrows) after spinal cord transection. C,D: Dorsal cells exhibited pronounced morphological changes after spinal cord injury. Note the degenerative morphological features of a dorsal cell perikaryon in the transected spinal cord, exhibiting condensed cytoplasm (white arrow in D), compared with a normal dorsal cell in the uninjured spinal cord (C). C: asterisks, nucleus of dorsal cell; white arrow, dorsal cells; cc, central canal. D: white arrow, condensed dorsal cells; cc, central canal. Toluidine blue O stain. E–M: Adequacy of probe penetration and sense probe control. E: Sema3 mRNA in situ hybridization on paraffin sections of the spinal cord showed intense labeling of neurons in gray matter, dorsal cells (white arrow), and probably lateral interneurons (black arrow). A similar distribution was observed for netrin mRNA in situ signal (F). Dorsal cells (white arrow) and probably lateral interneurons (black arrow). Asterisks, axons; cc, central canal. Control DIG-labeled sense Sema3 RNA (G) and netrin RNA (H) probes did not produce a hybridization signal; Mth, Mauthner axon; I1 and M3, axons of reticulospinal neurons I1 and M3. The spinal cord wholemount in situ hybridization showed abundant Sema3 (I) and netrin (J) mRNA expression with distribution of labeled neurons very similar to signal distribution after in situ hybridization on paraffin sections. I: GM, gray matter; cc, central canal; black arrows point to dorsal cells and black arrowhead: edge cells. J: GM, gray matter; cc, central canal; black arrows point to dorsal cells; white arrow: lateral interneurons and black arrowhead: edge cells. Wholemounted spinal cords were hybridized with control DIG-labeled sense Sema3 (L) and netrin (M) RNA probes and had no labeling. Scale bars = 100 μm in A,E (applies to E–M); 20 μm in C.

In situ hybridization on paraffin sections

Lampreys were anesthetized in 0.1% tricaine methane-sulfonate and 1.5-cm lengths of animal were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3.5 hours with rocking. After fixation, tissues were rinsed overnight in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C, dehydrated in serial ethanols, and embedded in paraffin. Sections 8 μm thick were mounted on “Superfrost/Plus” slides (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA). The mounted sections were deparaffinized and processed for in situ hybridization overnight in hybridization buffer containing 0.5 μg/μL digoxigenin-labeled antisense or sense RNA probe at 50°C. After hybridization, sections were washed in 2× SSC, treated with 20 μg/mL RNase A for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed in 0.2× SSC at 50°C. Detection and signal development were performed as discussed above for wholemount preparations. A DIG-labeled sense RNA probe was used as an internal control and did not produce a hybridization signal (Fig. 1G,H). In order to avoid artifactual differences in labeling strength among spinal cords from different times after transection, the times that animals were lesioned were staggered and positive controls included for all timepoints, so that all the spinal cords were processed at the same time and under the same conditions.

Procedure for Nissl staining of spinal cord

Nissl staining was performed with Toluidine blue O according to our previously published protocol (Selzer, 1979). Briefly, the spinal cord was removed from anesthetized animals by a dorsal approach and treated with 0.1% collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 3 hours, washed three times in lamprey Ringer solution, and stained in 1% Toluidine blue O (1 g Toluidine blue O, 6 g borax [NaB4O7], 1 g boric acid, and distilled water to 100 mL) at 37°C for 20 minutes. Excess stain was removed by rinsing in distilled water and the stain was differentiated in Bodian #2 fixative (5 mL formalin, 90 mL 80% ethanol, 5 mL glacial acetic acid) for 7 minutes. The tissue was dehydrated in 95% and 100% ethanol, cleared in cedarwood oil for 1–4 hours, and mounted in Pro-Texx Mounting Medium.

Lectin histochemistry

To identify microglial cells, wholemounts were labeled with GSA isolectin I-B4 after semaphorin- or netrin-labeled cells were revealed colorimetrically by in situ hybridization. The spinal cord wholemounts were washed in PBS and incubated with Fluorescein-labeled GSL I-isolectin B4 (5 μg/mL Griffonia (Bandeiraea) simplicifolia lectin I GSL I-B4; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), which is a specific marker for microglia and labels D-galactose residues that are expressed by both resting and activated microglial cells (Streit and Kreutzberg, 1987; Streit, 1990; Boya et al., 1991). Each step was followed by washing three times for 10 minutes with PBS. Wholemounts were coverslipped in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories) and observed under a Carl Zeiss fluorescence microscope. Control for lectin staining consisted of 1) treating tissue prior to staining with α-galactosidase from coffee beans (Sigma) at 1 U/mL in phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.1) for 2 hours at 37°C; and 2) incubating with GSA I-B4 in the presence of 0.1 M melibiose (6-0-α-D-galactopyranosyl-D-glucose) to saturate lectin binding sites and prevent interaction with sugars of tissue components.

RESULTS

The lampreys and hagfishes are the most primitive living vertebrates and their spinal cords exhibit primitive features. Most notably, myelin is absent in the nervous system of these animals (Bullock et al., 1984) and blood vessels do not enter the spinal cord parenchyma. However, the organization of the lamprey spinal cord follows the basic vertebrate plan and is well suited for histological analysis because it is flat and transparent, allowing visualization of nerve cell bodies and axons. Most neuronal and glial cell bodies are located in the central “gray matter” with axon tracts surrounding them (Fig. 1A,E,F). The spinal cord of the lamprey consists of ≈100 segments, and cell counts indicate that each segment contains ≈1,000 neurons (Rovainen, 1979). Several classes of neurons can be recognized in the spinal cord on the basis of morphological and physiological features such as axonal projection, perikaryon size/location, and other visual cues (Fig. 1A) (Rovainen, 1974; Selzer, 1979). Dorsal cells are identified as large (up to 60 μm in diameter), round cells dorsolateral to the central canal. They number about seven to nine per hemisegment of spinal cord. Most dorsal cells are bipolar, with axons extending rostrally and caudally in the dorsal axon tracts, and they lack the prominent dendrites of other spinal neurons. The ascending axon of dorsal cells is the longest and can be stimulated electrically from the rostra1 spinal cord. A large fraction of dorsal cells in the larval spinal cord could be stimulated from the rostral medulla and isthmus on the same side (Rovainen, 1967, 1979). Lateral cells are the largest interneurons in the rostral half of the lamprey spinal cord. They can be recognized by the following morphological characteristics: a large perikaryon (typically 60 by 100 μm) at the border of the gray matter and the lateral tract of the cord, transverse orientation of cell body and dendrites, lack of contralateral processes, one or a few stout dendrites extending to the ventrolateral corner of the cord, and a medium-sized axon extending ipsilaterally toward the tail. About 50–100 lateral cells per animal can be recognized in the gill and trunk regions of the spinal cord (Selzer, 1979), although smaller cells of the same type may also be present (Rovainen, 1979; Buchanan, 2001). “Edge cells” identified as neurons are situated in the lateral fiber tracts, often against the ventrolateral edge of the spinal cord. These cells are rather numerous, about 20 per hemisegment, and are heterogeneous in shape, in size (sometimes more than 50 μm in diameter), and in projections of their axons (Rovainen, 1979; Selzer, 1979). Many of the medium-sized nerve cells are propriospinal interneurons and although a few identified motoneurons are large, most are medium-sized (Rovainen, 1979; Buchanan, 2001).

Gross cytoarchitecture of the spinal cord after transections

Previous experimental data suggested some morphological changes in the transected lamprey spinal cord (Yin et al., 1981, 1987). Therefore, we analyzed the cytoarchitecture of the spinal cord in unlesioned animals and caudal to a spinal transection site at comparable spinal levels (5th–7th gill region, 1–3 mm caudal to the lesion site). The gross cytoarchitecture of the spinal cord caudal to the lesion site remained largely intact and spinal “gray matter” could be discerned clearly in wholemounts that were stained with Toluidine blue (Fig. 1A,B). However, dorsal cells exhibited pronounced morphological changes after spinal cord injury, characterized by shrinkage and loss of Nissl substance. As shown in Figure 1C,D, many pyknotic cells appeared in the spinal cord 1 month after transection. We found dorsal neuron perikarya with dense, shrunken cytoplasm (Fig. 1D). In contrast, in control animals pyknotic cells never appeared. Some degenerated cells with a pyknotic nucleus were first observed close to the lesion site in Nissl-stained spinal cord on day 14 after axotomy (data not shown). Almost all of the degenerating dorsal cells were identifiable as such in spinal cord at 30 days postlesion. Additionally, these changes were inversely related to the distance of the dorsal cells from the transection site.

Adequacy of probe penetration

In order to determine whether the RNA probe was reaching neurons deep within the parenchyma, the spinal cord wholemount preparation (Fig. 1I,J) was compared with preparations in which in situ hybridization was performed on paraffin sections (Fig. 1E,F). No differences in the distribution of labeled neurons were observed. For example, dorsal cells are located ≈150 μm below the dorsal surface of the cord, close to the midline, and nearly midway between the dorsal and ventral surfaces. Yet dorsal cells were equally well-labeled by in situ hybridization in wholemounts and paraffin sections.

Cellular localization of netrin message

The optimized wholemount in situ hybridization protocol was used to examine expression patterns of netrin mRNA, which was expressed throughout the spinal cord. Label was found most prominently in dorsal cells and in medium-sized neurons in the lateral gray matter (Figs. 1F,J, 2A). Label was also found in the glial/ependymal cells surrounding the central canal and in many small (presumably glial) cells throughout the gray matter. We also found labeling in most edge cells and some lateral interneurons—all identified cell types with previously described patterns of axonal projection (Rovainen, 1967; Rovainen, 1974; Tang and Selzer, 1979; Grillner et al., 1984).

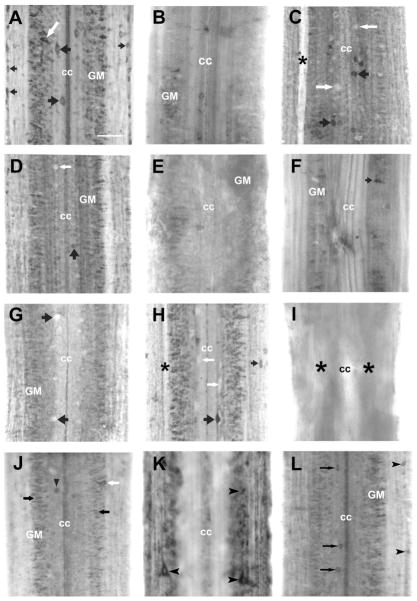

Fig. 2.

Expression of netrin mRNA in the spinal cord after transection. Rostral is top in all micrographs. The entire width of the cord is seen. A: In situ hybridization in wholemounted control spinal cord shows labeling for lamprey netrin very prominently in dorsal cells (black arrows), in neurons of the spinal gray matter (GM) (white arrow), and in the edge cells (small black arrows). The ependymal cells lining the central canal (cc) also express netrin. B–D: Netrin mRNA expression 2 weeks after spinal cord transection. B,C: Netrin mRNA expression was strongly downregulated 500 μm caudal and rostral to transection in the neurons of the spinal gray matter (GM). Only a few dorsal cells (black arrows) expressed netrin mRNA, while most dorsal cells stopped expressing netrin mRNA (the clear silhouettes of dorsal cells are indicated by white arrows); asterisk: a swollen, degenerating Mauthner axon. D: Typical, though much less intensely labeled, netrin-expressing neurons remained in the spinal gray matter (GM) far (1 cm) from the transection site; a few dorsal cells continued to express netrin mRNA (black arrow), while most dorsal cells stopped expressing netrin mRNA; a clear DC silhouette is indicated by white arrow. E–H: By 4 weeks posttransection, no netrin-expressing neurons were found 500 μm caudal (E) or rostral (F) to the transection site; 1 mm caudal to transection site (G) a few neurons in the spinal cord gray matter (GM) express netrin mRNA but dorsal cells do not; the clear silhouettes of dorsal cells are indicated by black arrows. H: Netrin expression in neurons of the spinal gray matter 10 mm caudal to the transection was almost at pretransection levels; however, most dorsal cells still did not express netrin (white arrow). A netrin-expressing dorsal cell is indicated by the large black arrow and an edge cell indicated by the small black arrow; asterisk: swollen degenerating Mauthner axon. I–L: Netrin mRNA expression 5 months after spinal cord transection. I: Absence of in situ hybridization signal for netrin in spinal cord around transection site; cc, central canal; asterisks, transection site. J–L: Netrin mRNA expression gradually returned to prelesion levels. J: Netrin expression in neurons of the spinal gray matter (black arrows), a dorsal cell (black arrowhead), and a lateral cell (white arrow) located ≈500 μm caudal to the transection site. K: 500 μm rostral to the transection site several neurons expressing netrin mRNA (black arrowheads). Further caudal from the transection, 10 mm (L) netrin in situ hybridization patterns were similar to those in control animals; label was seen in dorsal cells (black arrows), edge cells (black arrowheads), and neurons of the spinal gray matter (GM) and in the ependymal cells lining the central canal (cc). Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to all).

Netrin mRNA expression after spinal cord transection

At 14 days after spinal cord transection, netrin mRNA expression was strongly downregulated 500 μm caudal (and rostral) to the transection (Fig. 2B,C) in neurons of the spinal gray matter. Only a few dorsal cells continued to express netrin mRNA. With increasing distance from the transection, expression of netrin mRNA appeared in the usual distribution, although at 10 mm it remained less than control, with only a few dorsal cells labeled (Fig. 2D). Four weeks after spinal cord transection, no neurons expressed netrin mRNA at 500 μm caudal and rostral to the transection site (Fig. 2E,F). More caudally (1 mm), a few neurons in the spinal cord gray matter expressed netrin mRNA but dorsal cells remained unlabeled (Fig. 2G). At 10 mm caudal to the transection, netrin expression was almost at pretransection levels in neurons of the spinal gray matter. However, most dorsal cells remained unlabeled (Fig. 2H).

Previous studies of spinal-transected lampreys showed a gradual increase in the numbers of restored descending projections with increasing recovery times (Davis and Mc-Clelland, 1994). In order to elucidate the long-term effect of spinal cord transection on message levels for axon guidance molecules, we examined the mRNA expression patterns of netrin in the spinal cord of larval lampreys 5 months after injury. The transection site was easily identified in wholemount spinal cord preparations by a narrowing of the spinal cord and widening of the central canal (Fig. 2I). The transection zone was ≈500 μm long (our observation and Yin and Selzer, 1983). Netrin mRNA expression was not detected at the lesion site (Fig. 2I) but was present at reduced levels (compared to control) in longitudinally arrayed medium-sized neurons in the spinal gray matter, and in dorsal cells and lateral interneurons at 500 μm from transection site (Fig. 2J,K). Expression increased with distance from the transection, but the intensity of netrin-specific in situ hybridization signal and the number of netrin-producing neurons were still noticeably reduced at 10 mm (Fig. 2, compare L with A), gradually returning to prelesion levels at greater distances from the lesion. This labeling was found primarily in dorsal cells, edge cells, neurons of the spinal gray matter, and in the ependymal cells lining the central canal.

Cellular localization of Sema4 mRNA

Expression of Sema4 mRNAs in spinal cord was determined by wholemount in situ hybridization. A high level of Sema4 mRNA expression was found along the length of the intact spinal cord. Label was found primarily in the neurons of the lateral gray matter and occasionally in the dorsal cells and in the edge cells (Fig. 3A).

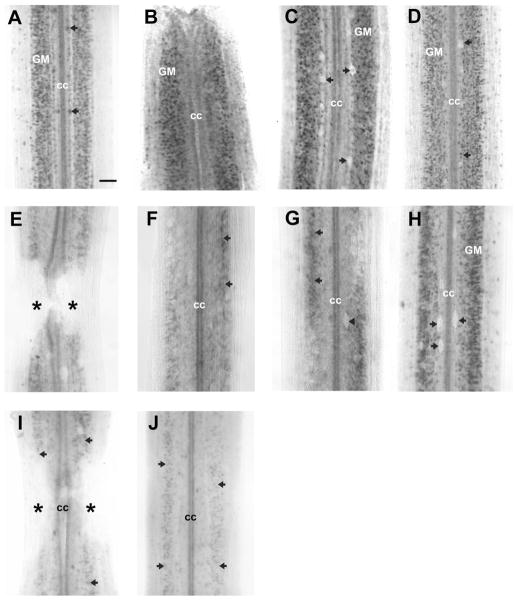

Fig. 3.

Effect of transection on expression of Sema4 mRNA. In situ hybridization was performed in spinal cord wholemounts. Rostral is top in all micrographs. The entire width of the cord is seen. A: In control animals, labeling for Sema4 was seen prominently in dorsal cells (black arrows), neurons of the gray matter (GM), and in the ependymal cells lining the central canal (cc). B–D: At 2 weeks post-transection, Sema4 mRNA expression was not changed at the transection site (B) and 500 μm caudal to transection (C) and 10 mm caudal to the lesion (D), except for disappearance of Sema4 mRNA expression in dorsal cells. The unlabeled silhouettes of dorsal cells are indicated by black arrows. E: At 30 days, semaphorin-positive cells surrounded the lesion site but never were found in the scar region; asterisks: transection site. F,G: By 4 weeks posttransection, fewer neurons (black arrows) expressed Sema4 mRNA 500 μm rostral (F) and caudal (G) to transection. The silhouette of an unlabeled dorsal cell is indicated by the black arrowhead. H: With increasing distance from the transection, expression of Sema4 mRNA appeared in the usual distribution, although at 10 mm it remained less than control, and expression was absent in dorsal cells. I,J: At 5 months after spinal cord transection, Sema4 mRNA expression was downregulated in neurons of the spinal gray matter (black arrows) around transection site (I) and at 2 mm caudal to the lesion (J), and expression was absent in dorsal cells and edge cells (J); cc, central canal; asterisks, transection site. Scale bar = 100 μm in A (applies to all).

Sema4 mRNA expression after spinal cord transection (Fig. 3B–J)

The spatiotemporal expression of Class 4 semaphorin mRNA in spinal cord was analyzed at 14 days, 30 days, and 5 months after injury, using wholemount in situ hybridization. At 14 days after spinal cord transection, Class 4 semaphorin mRNA was expressed abundantly in the longitudinally arrayed Sema4-expressing neurons of the spinal cord gray matter (Fig. 3B), although expression was absent in dorsal and edge cells (Fig. 3C,D). At 30 days the expression had declined somewhat but semaphorin-positive cells were still present along of the length of the spinal cord. Semaphorin-positive cells were found in the spinal cord just rostral and caudal to the scar but not within the scar itself (Fig. 3E). Sema4 mRNA expression was downregulated 500 μm rostral and caudal to transection (Fig. 3F,G) in the neurons of the spinal gray matter. With increasing distance from the transection, expression of Sema4 mRNA appeared in the usual distribution, although at 10 mm it remained less than control, and expression was absent in dorsal cells (Fig. 3H). Five months after spinal cord transection, Sema4 mRNA expression was downregulated in neurons of the spinal gray matter near the transection site (Fig. 3I) and at 2 mm caudal to the lesion, although expression was absent in dorsal and edge cells (Fig. 3J) compared to expression patterns in control animals (Fig. 3A).

Cellular localization of Sema3 mRNA

Expression of Sema3 mRNA in spinal cord was determined by wholemount in situ hybridization. Wholemounts hybridized with control sense probes exhibited no hybridization signal (Fig. 1L). In the intact spinal cord, Sema3 mRNA in situ hybridization showed labeled dorsal cells and medium-sized neurons in the lateral gray matter (Figs. 1I, 4A). Label was also found in the glial/ependymal cells surrounding the central canal and in most edge cells (Fig. 4A).

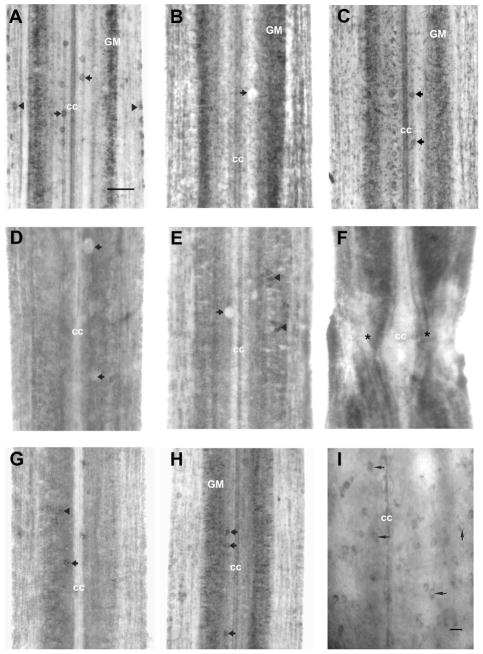

Fig. 4.

Effect of transection on expression of Sema3 mRNA. Rostral is top in all micrographs. The entire width of the cord is seen. A: In situ hybridization in control spinal cord wholemount shows labeled dorsal cells (black arrows) and medium-sized neurons in the lateral gray matter (GM). Label was also found in the glial/ependymal cells surrounding the central canal (cc) and in most edge cells (black arrowhead). B,C: Two weeks after spinal cord transection. B: Sema3 mRNA expression was upregulated near the lesion site (1 mm) compared to control animals, although expression was absent in dorsal cells (black arrow); cc, central canal. C: The intensity of labeling decreased with distance from the transection but it was above control levels 20 mm caudal to the transection; dorsal cells (black arrow); cc, central canal. D–F: One month after transection. D: No neurons expressed Sema3 mRNA at 1 mm caudal to the transection site; the clear silhouettes of dorsal cells are indicated by white arrows; cc, central canal. High background is seen on this frame due to nonspecific binding of label to cellular debris and blood cells entering the transection site. E: More caudally (20 mm), a few neurons in the spinal cord gray matter expressed Sema3 mRNA (black arrowheads) but dorsal cells remained unlabeled (black arrows point to the silhouettes of dorsal cells); cc, central canal. F: Five months after spinal cord transection Sema3 mRNA expression was not detected at the lesion site (asterisks: transection site). G: Reduced level of Sema3 mRNA expression was detected 1 mm caudal from the transection site in neurons (black arrowhead) of the spinal gray matter and in some dorsal cells (black arrow). H: expression increased with distance from the transection, but the intensity of Sema3-specific in situ hybridization signal and the number of Sema3-producing neurons were still noticeably reduced at 20 mm. Labeling was found primarily in medium-sized neurons in the spinal gray matter (GM) and in dorsal cells (black arrows); cc, central canal. I: Microglial cells that expressed Sema3 were located on the surface of the spinal cord (black arrows). Scale bars = 100 μm in A; 20 μm in I.

Sema3 mRNA expression after spinal cord transection (Fig. 4B–H)

Two weeks after spinal cord transection, compared to control animals (Fig. 4A), Sema3 mRNA signal was increased near the lesion site (Fig. 4B). Some of the signal was in cells of the gray matter that were large enough to be neurons and some was in very small cells of the gray and white matter, presumably glial cells, although expression was absent in dorsal cells (Fig. 4B). The intensity of labeling decreased with distance from the transection but it was above control levels 20 mm caudal to the transection (Fig. 4C). By 4 weeks, no neurons expressed Sema3 mRNA at 1 mm caudal to the transection site (Fig. 4D). More caudally (20 mm), a few neurons in the spinal cord gray matter expressed Sema3 mRNA but dorsal cells remained unlabeled (Fig. 4E). Sema3 expression by nonneuronal (presumably glial) cells was apparently increased in the spinal cord (Fig. 4D,E). Five months after spinal cord transection, Sema3 mRNA expression was not detected at the lesion site (Fig. 4F). Greatly reduced levels (compared to control) of Sema3 mRNA expression was detected in neurons 1 mm caudal to the transection site (Fig. 4G). Expression increased with distance from the transection, but the intensity of Sema3-specific in situ hybridization signal and the number of Sema3-producing neurons were still noticeably reduced at 20 mm (Fig. 4, compare H with A). This labeling was found primarily in longitudinally arrayed medium-sized neurons in the spinal gray matter, in dorsal cells, and in the ependymal cells lining the central canal.

Identification of the nonneuronal Sema3-expressing cell types in lamprey spinal cord after injury

During our examination of netrin, Sema4, and Sema3 expression in the transected spinal cord we detected populations of small, seemingly nonneuronal cells that expressed Sema3 (Fig. 4B,C) but not netrin or Sema4 (data not shown). By their sizes and shapes, they may be microglial cells (Streit and Kreutzberg, 1987; Streit, 1990; Boya et al., 1991). They were located on the surface of the spinal cord (Fig. 4I), although some of them were located just under the cord surface.

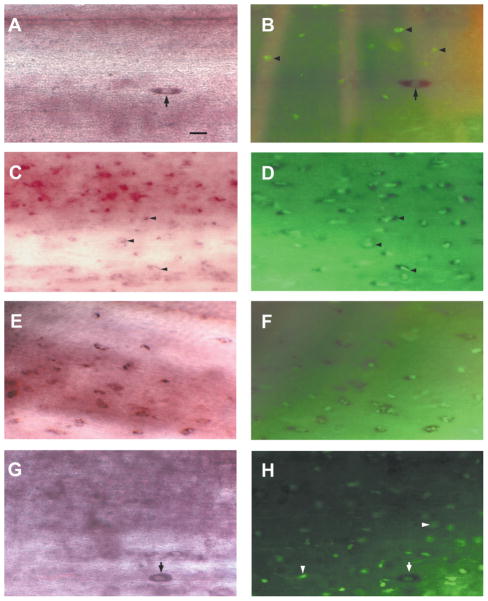

Microglial cell activation after spinal cord transection

Fluorescein-labeled GSL I-isolectin B4, which has been used previously to reveal macrophages/microglial cells in spinal cord and brain (Streit and Kreutzberg, 1987; Streit, 1990; Boya et al., 1991), was used here to analyze the macrophage/microglial response in the spinal cord 0.5–10 mm caudal to the lesion site at 14 days, 30 days, and 5 months after transection. To determine whether the Sema3-labeled cells in the spinal cord are microglial cells, lectin histochemistry was performed after Sema3 in situ hybridization (Fig. 5A–H). In normal cord, small subsets of slender, elongated Sema3-expressing cells were detected on the surface of control spinal cords (Fig. 5A). Although these cells displayed morphological hallmarks of resting microglia—their cell bodies were spindle-shaped and contained an elongated nucleus—none of these Sema3-expressing cells were also labeled with IB4 lectin, which labeled resting and activated macrophages/microglial cells. However, several lectin-positive cells were seen in control spinal cord (Fig. 5B). Therefore, positive identification of these Sema3-expressing cells was not resolved, leaving the possibility that some of them might be small neurons or astrocytes. The specificity of the lectin histochemical staining was confirmed by the complete elimination of staining if the Fluorescein-labeled GSL I-isolectin B4 was preincubated in the presence of 0.1 M melibiose, or if the tissue was treated with α-galactosidase from coffee beans (Sigma) prior to staining (data not shown). Following injury, cellular elements of noticeably different shape were labeled in the spinal cord. These cells were rounded, reminiscent of activated microglia/macrophages (Fig. 5C). Moreover, no cells larger than 5 μm or possessing obvious neuronal morphology were labeled with Sema3. At 14 days postlesion, the number of Sema3-expressing cells increased dramatically 0.5–10 mm caudal to the injury site (Fig. 5C). In the first 2 weeks following axotomy, a dramatic and rapid accumulation of reactive macrophages/microglial cells was observed throughout the spinal cord, as evidenced by increasing IB4-lectin reactivity (Fig. 5D). Most of the lectin-labeled cells coexpressed Sema3 (Fig. 5D). Microglial Sema3-expression was also examined 30 days after spinal cord transection. The localization and shapes of Sema3-expressing microglia/macrophages resembled those at 14 days (Fig. 5E,F). Sema3-positive macrophages/microglial cells were largely absent from the spinal cord 5 months after injury. A few cells that expressed Sema3 mRNA resembled the small spindle-shaped cells in control spinal cord (Fig. 5G). However, none of these cells were labeled by IB4-lectin and thus they were not likely to be macrophages/microglial cells (Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

Microglial activation after spinal cord transection. Rostral is top in all micrographs. The entire width of the cord is seen. A: In situ hybridization in control spinal cord wholemount shows slender, elongated Sema3-expressing cells (black arrow) on the surface of the spinal cord. B: Fluorescein-labeled GSL I-isolectin B4 histochemistry reveals several lectin-labeled cells in control spinal cord (black arrowheads) but Sema3-expressing cells were not labeled (black arrow). C,D: Two weeks after spinal cord transection. C: At 14 days following injury increased numbers of small, rounded cells (black arrowheads), reminiscent of activated microglia/macrophages, were labeled with Sema3. D: A dense accumulation of reactive macrophages/microglial cells, as evidenced by increasing IB4-lectin reactivity, was seen in the spinal cord 2 weeks after transection. Most of the lectin-labeled cells coexpressed Sema3 mRNA (black arrowheads). E,F: One month after transection. E: Localization and shape of Sema3-expressing microglia/macrophages resembled that at 14 days. F: Intense lectin reactivity was seen in the spinal cord 4 weeks after transection. G,H: Microglial expression of Sema3 5 months after spinal cord transection. G: Only a few Sema3-positive cells were detected in the spinal cord 5 months after injury. Some slender, elongated Sema3-expressing cells (black arrowheads) resembled macrophages/microglial cells in control spinal cord (black arrow). H: Numerous macrophages/microglial cells (white arrowheads) could be detected by labeling with IB4 lectin in the spinal cord 5 months after injury. However, these never labeled with the Sema3 RNA probes. On the other hand, there were many elongated Sema3-expressing cells, but these were not reactive macrophages/microglial cells, as evidenced by lack of IB4-lectin reactivity (white arrow). Scale bar = 20 μm in A (applies to all).

DISCUSSION

Our present and previous work (Shifman and Selzer, 2000b, 2006) indicated that the spinal cord of the large larval (4–5 years old) lamprey contains many cells that produce netrin and semaphorins. The roles of these guidance molecules in embryonic development have been well described (Culotti and Kolodkin, 1996; Goodman, 1996; Kolodkin, 1998; Raper, 2000; Dickson and Keleman, 2002; Fiore and Puschel, 2003), but their functions in the post-natal CNS are less clear. Lamprey spinal neurons differentiate early in development (Whiting, 1957) and by the end of embryogenesis the large reticulospinal axons extend almost the entire length of the spinal cord. Therefore, these neurons are already past the axonal guidance and navigation stage. In mammals, several members of the semaphorin, ephrin, slit, and netrin families display sustained expression in adulthood (Giger et al., 1998a; Itoh et al., 1998; Encinas et al., 1999; Hirsch et al., 1999; Ellezam et al., 2001; Knoll et al., 2001; Manitt et al., 2001; Marillat et al., 2002; Himanen and Nikolov, 2003; Wehrle et al., 2005), where they might function in the maintenance of established connections by restricting spontaneous or aberrant axon sprouting.

The present study explored the effect of spinal cord transection on the expression of netrin and Class 3 and 4 semaphorins during the period of most intense regeneration. Netrin expression was decreased in neurons close to the transection at 2 and 4 weeks posttransection, and was still not back to normal after 5 months. There was little effect on expression remote (1.5 cm) from the transection site. The expression of the secreted semaphorin Sema3 was upregulated close to the lesion site at 2 weeks after transection. The intensity of labeling decreased with distance from the transection but it was above control levels 10 mm caudal to the transection. By 4 weeks, no neurons expressed Sema3 mRNA at 1 mm caudal to the transection site. The expression of the transmembrane semaphorin Sema4 declined from high to moderate levels.

Some effects of spinal cord transection on expression of guidance molecules could be explained as direct consequences of axotomy, e.g., the complete loss of netrin, Sema3, and Sema4 mRNA expression from the dorsal cells close to the transection site, which strongly expressed netrin, Sema3, and Sema4 in control animals. Dorsal cells are primary sensory neurons arrayed in two distinct rows on either side of the midline (Rovainen, 1967, 1979). Most project to the rostral spinal cord (Tang and Selzer, 1979) and are thus axotomized by the high-level spinal cord transection in the present study. Corresponding morphological and electrophysiological changes described previously in axotomized dorsal cells were maximal at 3 weeks and, like the loss of Sema3 and Sema4 expression, the intensities of those changes were also inversely related to the distance of the cell from the transection (Yin et al., 1981). The intensity of the morphological changes and loss of mRNA expression for netrin and semaphorins in dorsal cells after spinal cord transection might contribute to the relative inability of dorsal cells to regenerate their axons compared to other types of spinal neurons (Yin and Selzer, 1983; Armstrong et al., 2003).

Netrin

Although netrin expression has been studied extensively in mammals during embryonic spinal cord development (Serafini et al., 1994; Kennedy et al., 1994; Colamarino and Tessier-Lavigne, 1995; Serafini et al., 1996), it has not been studied much in the adult spinal cord. In situ hybridization demonstrated that cells in both white and gray matter of the adult spinal cord express netrin-1 at levels similar to those in embryonic CNS (Manitt et al., 2001). Netrin-1 was expressed by multiple classes of spinal interneurons and motoneurons and by most, if not all, oligodendrocytes, but not by astrocytes (Manitt et al., 2001; Wehrle et al., 2005). These data are very similar to our own, which showed widespread expression of netrin in the lamprey spinal cord, although lampreys lack myelin and thus have no oligodendrocytes (Bullock et al., 1984). On the other hand, the effect of spinal cord injury on netrin expression in lampreys is very different from that in rodents. In lamprey, netrin mRNA expression was significantly decreased within the lesion and in nearby neurons at 2 and 4 weeks posttransection. By contrast, in the mouse netrin expression remained unchanged post-transection in neurons, and was upregulated 8 days after injury within the lesion site, probably in macrophages/activated microglial cells or meningeal fibroblastic cells (Wehrle et al., 2005).

Several recent articles have attempted to correlate expression of netrin with axonal regeneration in the other parts of the CNS. In adult rat, netrin-1 was not detected immunohistochemically in the optic nerve, either normally or after optic nerve crush, although it appeared transiently after a piece of peripheral nerve was grafted onto the proximal cut end of the optic nerve (Petrausch et al., 2000). On the other hand, netrin was present in the optic nerves of fish, and netrin-1-Fc fusion protein bound to regenerating optic nerve axons, suggesting that netrin signaling may be active during regeneration of optic nerve in the fish but not in the rat. Nerve grafting experiments in adult rat retina showed that netrin-1 mRNA was constitutively expressed by retinal ganglion cells regenerating an axon into a peripheral nerve graft (Ellezam et al., 2001) and that the netrin message was present in glial cells associated with regenerating axons.

Semaphorins

Semaphorin Class 3 expression in uninjured lamprey spinal cord had a pattern similar to that in mature mammalian spinal cord, where several Class 3 semaphorins were expressed in spinal motoneurons and in several other neuronal subtypes in the gray matter (De Winter et al., 2002; Hashimoto et al., 2004; see however Pasterkamp et al., 1999). By contrast, while in the present and a previous (Shifman and Selzer, 2006) study, Sema4 showed strong expression in the lamprey spinal cord, in the adult mammalian spinal cord it showed a lack of neuronal expression (Moreau-Fauvarque et al., 2003). Semaphorin expression has also been studied in fish, but only during embryonic development (Halloran et al., 1998, 1999; Shoji et al., 1998; Yee et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2004).

Sema4

Sema4 mRNA expression was strong in neurons of uninjured lamprey spinal cord (see also Shifman and Selzer, 2006), but by 4 weeks posttransection expression had declined from high to moderate levels. Conversely, neurons of the uninjured mammalian spinal cord showed no Sema4 mRNA expression (Moreau-Fauvarque et al., 2003), but Sema4D expression was strongly upregulated in oligodendrocytes at the periphery of an injury, returning to normal levels 1 month postlesion (Moreau-Fauvarque et al., 2003). Sema4F mRNA was also upregulated in rat motoneurons 3 weeks after a lumbar spinal cord lesion (Lindholm et al., 2004).

Sema3

Following unilateral transection of the lateral olfactory tract in adult rats, transient upregulation of Sema3A mRNA occurred in cells of the leptomeningeal scar (Pasterkamp et al., 1999; De Winter et al., 2002) but not in neurons (Pasterkamp et al., 1997). Unilateral bulbectomy in rats led to increased mRNA expression for Sema3A and Sema3B in olfactory receptor neurons (Pasterkamp et al., 1998b; Williams-Hogarth et al., 2000). Several recent reports have described modulation of semaphorin expression by injury. Sema3A was upregulated in the fibroblast-like cells of the scar tissue but not in the neurons or glial cells, after penetrating injuries to the lateral olfactory tract, cortex, perforant pathway, and spinal cord (Pasterkamp et al., 1999). Those authors later showed that following transection of the adult rat spinal cord the genes encoding Sema3A, 3B, 3C, 3E, and 3F are expressed by fibroblasts in the core of the scar and in the meningeal sheath surrounding the lesion (De Winter et al., 2002). These data are very similar to our observations of upregulation of Sema3 in the lamprey spinal cord close to lesion site 2 weeks after transection. However, in our experiments Sema3-expressing cells were microglia and not fibroblast-like cells of the scar. Distribution of mRNA and protein for the axon guidance molecules Sema3A, 3F, and the semaphorin receptors neuropilin-1 and -2 was also examined after injury of rat lumbar spinal cord (Lindholm et al., 2004). In that study, Sema3A mRNA and protein were upregulated in the scar and in motoneurons from 3 days to 3 weeks after injury. Neuropilin-1 mRNA showed no change in axotomized motoneurons. However, in another study in the rat, Sema3A expression rapidly decreased in the spinal cord after complete transection, reaching its lowest level 1 day after injury. Thereafter, Sema3A expression levels recovered and were four-fifths of normal at 28 days. Double staining by in situ hybridization and fluorescence immunohistochemistry showed that Sema3A was expressed in spinal cord neurons, but not in glia (Hashimoto et al., 2004).

Possible roles of netrin and semaphorins in regeneration

Axon regeneration in the lamprey spinal cord is incomplete (Selzer, 1978; Yin and Selzer, 1983; Lurie and Selzer, 1991a; Davis and McClelland, 1993, 1994). Fewer than 50% of severed axons grow into the distal stump within 10–12 weeks posttransection, and most of those grow less than 1 cm beyond the transection site (Rovainen, 1976; Yin and Selzer, 1983; Lurie and Selzer, 1991a,c). The robust expression of Sema3, which is generally chemorepulsive, and the downregulation of netrin, which can sometimes be a chemoattractant, could contribute to the regenerative failure of some lamprey axons after spinal cord transection. Some studies of spinal-transected lampreys showed a gradual increase in the numbers of restored descending projections with long recovery times. For example, several reticulospinal neurons could regenerate their axons to more than 50 mm caudal to the transection by 32 weeks (Davis and McClelland, 1994). This would be consistent with our data showing long-term modified expression of semaphorins and netrin 5 months after injury. At 5 months posttransection Sema3 mRNA expression was not detected at the lesion site and it seriously reduced level (compared to control) was detected in neurons up to 20 mm caudal to the transection site. Sema4 mRNA expression was downregulated in neurons of the spinal gray matter within 500 μm caudal to the lesion as compared to control and 4 weeks posttransection animals. Because netrin may be both chemoattractive and chemorepulsive, the downregulation of netrin near the transection, and its partial return to normal levels at longer recovery times, is not easily interpreted, but would be consistent with continued regeneration.

Role of the scar

The lamprey differs from mammals in the composition of the transection “scar.” In the lamprey, this consists of a broadened central canal lined with ependymal cells and glial processes but no neuronal perikarya and relatively few glial cells (Lurie and Selzer, 1991b,c). Unlike the scar in lesioned mammalian spinal cord, which contains Sema3- and/or netrin-expressing cells (Pasterkamp et al., 1997, 1999; Wehrle et al., 2005), the transection scar in the lamprey spinal cord contained no semaphorin- or netrin-positive cells. This may partially explain observations that lamprey spinal axons grow preferentially through a hemisection scar rather than around it (Lurie and Selzer, 1991c).

Our findings suggest that in lamprey spinal cord, microglia/macrophages were activated and increased in numbers after injury, and this response continued for several weeks. In the normal adult CNS, microglia are distributed throughout the neural parenchyma and constitute a cell population that shows a slow turnover from either proliferation of the resident microglia or recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells through an intact blood–brain barrier (Lawson et al., 1992). Microglia react swiftly to pathological events. Activated microglia are involved in acute CNS injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases (Streit, 1994, 1996, 2002a,b), and microglial activation has been documented in the spinal cord after spinal cord injury (Popovich et al., 1997; Sroga et al., 2003). A highly characteristic feature of microglial activation and reactive microgliosis induced by acute neural injury is the massive, but usually transient, expansion of the microglial cell population. Microglial activation is characterized by a number of features, including a morphological transformation of individual microglia, induction of a wide range of myeloid markers, trophic factors, cytokines, free radicals, and nitric oxide and the acquisition of a phagocytic phenotype (Streit, 1994, 1996, 2002a,b; Xu et al., 1998; Dougherty et al., 2000; Hashimoto et al., 2005; Ladeby et al., 2005; Mueller et al., 2006). Macrophages/microglial cells may have important functions for axonal regrowth by secreting axonal growth inhibiting and/or promoting molecules (Streit, 1994, 1996, 2002a,b; Rabchevsky and Streit, 1997; Dougherty et al., 2000; Batchelor et al., 2002; Sandvig et al., 2004).

In the present study, a marked elevation and expansion of isolectin-B4 microglial labeling was detected 14 days after a lesion. The microglial reaction appeared to reach maximum intensity at 4 weeks, when reactive microglia are prominent throughout the spinal cord. Concurrent expression of Sema3 mRNA in reactive microglial cells in lamprey spinal cord following transection may contribute to the observed elevation in the level of Sema3 mRNA expression at 14 and 30 days after injury. We can only speculate about the functions of Sema3 expressed by microglia after spinal cord transection. Intense Sema3 expression may create an area around the transection site that will repel regenerating axons that express semaphorin receptors, and this could reduce the numbers of regenerating axons crossing the transection site.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Guixin Zhang and Cindy Laramore for excellent technical assistance

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant number: R01 NS38537 (to M.E.S.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Armstrong J, Zhang L, McClellan AD. Axonal regeneration of descending and ascending spinal projection neurons in spinal cord-transected larval lamprey. Exp Neurol. 2003;180:156–166. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(02)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnard D, Lohrum M, Uziel D, Puschel AW, Bolz J. Semaphorins act as attractive and repulsive guidance signals during the development of cortical projections. Development. 1998;125:5043–5053. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor PE, Porritt MJ, Martinello P, Parish CL, Liberatore GT, Donnan GA, Howells DW. Macrophages and microglia produce local trophic gradients that stimulate axonal sprouting toward but not beyond the wound edge. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:436–453. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya J, Carbonell AL, Calvo JL, Borregon A. Microglial cells in the central nervous system of the rabbit and rat: cytochemical identification using two different lectins. Acta Anat (Basel) 1991;140:250–253. doi: 10.1159/000147064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braisted JE, Catalano SM, Stimac R, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Shatz CJ, O’Leary DD. Netrin-1 promotes thalamic axon growth and is required for proper development of the thalamocortical projection. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5792–5801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brankatschk M, Dickson BJ. Netrins guide Drosophila commissural axons at short range. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:188–194. doi: 10.1038/nn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JT. Contributions of identifiable neurons and neuron classes to lamprey vertebrate neurobiology. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:441–466. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock TH, Moore JK, Fields RD. Evolution of myelin sheaths: both lamprey and hagfish lack myelin. Neurosci Lett. 1984;48:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani V, Rougon G. Control of semaphorin signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:532–541. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chedotal A, He Z, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III. Neuron. 1997;19:547–559. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80371-2. Erratum, Neuron, 1997;19:559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AH, Mackler SA, Selzer ME. Behavioral recovery following spinal transection: functional regeneration in the lamprey CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colamarino SA, Tessier-Lavigne M. The axonal chemoattractant netrin-1 is also a chemorepellent for trochlear motor axons. Cell. 1995;81:621–629. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culotti JG, Kolodkin AL. Functions of netrins and semaphorins in axon guidance. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GRJ, McClellan AD. Time course of anatomical regeneration of descending brainstem neurons and behavioral recovery in spinal-transected lamprey. Brain Res. 1993;602:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90252-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GR, McClelland AD. Extent and time course of restoration of descending brainstem projections in spinal cord-transected lamprey. J Comp Neurol. 1994;344:65–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro F, Hu L, Drabkin H, Sotelo C, Chedotal A. Chemoattraction and chemorepulsion of olfactory bulb axons by different secreted semaphorins. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4428–4436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04428.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Winter F, Oudega M, Lankhorst AJ, Hamers FP, Blits B, Ruitenberg MJ, Pasterkamp RJ, Gispen WH, Verhaagen J. Injury-induced class 3 semaphorin expression in the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:61–75. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiner MS, Kennedy TE, Fazeli A, Serafini T, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sretavan DW. Netrin-1 and DCC mediate axon guidance locally at the optic disc: loss of function leads to optic nerve hypoplasia. Neuron. 1997;19:575–589. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ, Keleman K. Netrins. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R154–155. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty KD, Dreyfus CF, Black IB. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia/macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:574–585. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellezam B, Selles-Navarro I, Manitt C, Kennedy TE, McKerracher L. Expression of netrin-1 and its receptors DCC and UNC-5H2 after axotomy and during regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cells. Exp Neurol. 2001;168:105–115. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JA, Kikuchi K, Chedotal A, de Castro F, Goodman CS, Kimura T. Cloning, expression, and genetic mapping of Sema W, a member of the semaphorin family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2491–2496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Hermiston ML, Tighe RV, Steen RG, Small CG, Stoeckli ET, Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Rayburn H, Simons J, Bronson RT, Gordon JI, Tessier-Lavigne M, Weinberg RA. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc) gene. Nature. 1997;386:796–804. doi: 10.1038/386796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner L, Koppel AM, Kobayashi H, Raper JA. Secreted chick semaphorins bind recombinant neuropilin with similar affinities but bind different subsets of neurons in situ. Neuron. 1997;19:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Puschel AW. The function of semaphorins during nervous system development. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s484–499. doi: 10.2741/1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger RJ, Pasterkamp RJ, Heijnen S, Holtmaat AJ, Verhaagen J. Anatomical distribution of the chemorepellent semaphorin III/collapsin-1 in the adult rat and human brain: predominant expression in structures of the olfactory-hippocampal pathway and the motor system. J Neurosci Res. 1998a;52:27–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980401)52:1<27::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger RJ, Urquhart ER, Gillespie SK, Levengood DV, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL. Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity [see Comments] Neuron. 1998b;21:1079–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CS. Mechanisms and molecules that control growth cone guidance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:341–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Williams T, Lagerback PA. The edge cell, a possible intraspinal mechanoreceptor. Science. 1984;223:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6691161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran MC, Severance SM, Yee CS, Gemza DL, Kuwada JY. Molecular cloning and expression of two novel zebrafish semaphorins. Mech Dev. 1998;76:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran MC, Severance SM, Yee CS, Gemza DL, Raper JA, Kuwada JY. Analysis of a zebrafish semaphorin reveals potential functions in vivo. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:13–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199901)214:1<13::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin M, Zhou Y, Su MW, Scott IM, Culotti JG. Expression of the UNC-5 guidance receptor in the touch neurons of C. elegans steers their axons dorsally. Nature. 1993;364:327–330. doi: 10.1038/364327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Ino H, Koda M, Murakami M, Yoshinaga K, Yamazaki M, Moriya H. Regulation of semaphorin 3A expression in neurons of the rat spinal cord and cerebral cortex after transection injury. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2004;107:250–256. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0805-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Nitta A, Fukumitsu H, Nomoto H, Shen L, Furukawa S. Inflammation-induced GDNF improves locomotor function after spinal cord injury. Neuroreport. 2005;16:99–102. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuropilin is a receptor for the axonal chemorepellent semaphorin III. Cell. 1997;90:739–751. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen JP, Nikolov DB. Eph receptors and ephrins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:130–134. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Hu LJ, Prigent A, Constantin B, Agid Y, Drabkin H, Roche J. Distribution of semaphorin IV in adult human brain. Brain Res. 1999;823:67–79. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K, Hinck L, Nishiyama M, Poo MM, Tessier-Lavigne M, Stein E. A ligand-gated association between cytoplasmic domains of UNC5 and DCC family receptors converts netrin-induced growth cone attraction to repulsion. Cell. 1999;97:927–941. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh A, Miyabayashi T, Ohno M, Sakano S. Cloning and expressions of three mammalian homologues of Drosophila slit suggest possible roles for slit in the formation and maintenance of the nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;62:175–186. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Hinck L, Leonardo ED, Chan SS, Culotti JG, Tessier-Lavigne M. Deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) encodes a netrin receptor. Cell. 1996;87:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleman K, Dickson BJ. Short- and long-range repulsion by the Drosophila Unc5 netrin receptor. Neuron. 2001;32:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TE, Serafini T, de la Torre JR, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrins are diffusible chemotropic factors for commissural axons in the embryonic spinal cord. Cell. 1994;78:425–435. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsukawa T, Shimizu M, Sanbo M, Hirata T, Taniguchi M, Bekku Y, Yagi T, Fujisawa H. Neuropilin-semaphorin III/D-mediated chemorepulsive signals play a crucial role in peripheral nerve projection in mice. Neuron. 1997;19:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B, Isenmann S, Kilic E, Walkenhorst J, Engel S, Wehinger J, Bahr M, Drescher U. Graded expression patterns of ephrin-As in the superior colliculus after lesion of the adult mouse optic nerve. Mech Dev. 2001;106:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin AL. Semaphorin-mediated neuronal growth cone guidance. Prog Brain Res. 1998;117:115–132. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin AL, Matthes DJ, O’Connor TP, Patel NH, Admon A, Bentley D, Goodman CS. Fasciclin IV: sequence, expression, and function during growth cone guidance in the grasshopper embryo. Neuron. 1992;9:831–845. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin AL, Matthes DJ, Goodman CS. The semaphorin genes encode a family of transmembrane and secreted growth cone guidance molecules. Cell. 1993;75:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladeby R, Wirenfeldt M, Garcia-Ovejero D, Fenger C, Dissing-Olesen L, Dalmau I, Finsen B. Microglial cell population dynamics in the injured adult central nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Gordon S. Turnover of resident microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1992;48:405–415. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Ackerman SL, Tessier-Lavigne M. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature. 1997;386:833–838. doi: 10.1038/386833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm T, Skold MK, Suneson A, Carlstedt T, Cullheim S, Risling M. Semaphorin and neuropilin expression in motoneurons after intraspinal motoneuron axotomy. Neuroreport. 2004;15:649–654. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200403220-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo YL, Raible D, Raper JA. Collapsin: a protein in brain that induces the collapse and paralysis of neuronal growth cones. Cell. 1993;75:217–227. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80064-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie DI, Selzer ME. Axonal regeneration in the adult lamprey spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1991a;306:409–416. doi: 10.1002/cne.903060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie DI, Selzer ME. The need for cellular elements during axonal regeneration in the sea lamprey spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1991b;112:64–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90114-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie DI, Selzer ME. Preferential regeneration of spinal axons through the scar in hemisected lamprey spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1991c;313:669–679. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackler SA, Selzer ME. Specificity of synaptic regeneration in the spinal cord of the larval sea lamprey. J Physiol (Lond) 1987;388:183–198. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackler SA, Yin HS, Selzer ME. Determinants of directional specificity in the regeneration of lamprey spinal axons. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1814–1821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-06-01814.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitt C, Kennedy TE. Where the rubber meets the road: netrin expression and function in developing and adult nervous systems. Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:425–442. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitt C, Colicos MA, Thompson KM, Rousselle E, Peterson AC, Kennedy TE. Widespread expression of netrin-1 by neurons and oligodendrocytes in the adult mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3911–3922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03911.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marillat V, Cases O, Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sotelo C, Chedotal A. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of slit and robo genes in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442:130–155. doi: 10.1002/cne.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K, Furuyama T, Takahara M, Fujioka S, Kurinami H, Inagaki S. Sema4D stimulates axonal outgrowth of embryonic DRG sensory neurones. Genes Cells. 2004;9:821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song HJ, Berninger B, Holt CE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM. cAMP-dependent growth cone guidance by netrin-1. Neuron. 1997;19:1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Kennedy T. Axon guidance during development and regeneration. In: Selzer ME, Cohen LG, Duncan PW, Gage FH, editors. Textbook of neural repair and rehabilitation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 326–345. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Fauvarque C, Kumanogoh A, Camand E, Jaillard C, Barbin G, Boquet I, Love C, Jones EY, Kikutani H, Lubetzki C, Dusart I, Chedotal A. The transmembrane semaphorin Sema4D/CD100, an inhibitor of axonal growth, is expressed on oligodendrocytes and up-regulated after CNS lesion. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9229–9239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09229.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CA, Schluesener HJ, Conrad S, Pietsch T, Schwab JM. Spinal cord injury-induced expression of the immune-regulatory chemokine interleukin-16 caused by activated microglia/macrophages and CD8+ cells. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:233–240. doi: 10.3171/spi.2006.4.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura F, Tanaka M, Takahashi T, Kalb RG, Strittmatter SM. Neuropilin-1 extracellular domains mediate semaphorin D/III-induced growth cone collapse. Neuron. 1998;21:1093–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Verhaagen J. Emerging roles for semaphorins in neural regeneration. Brain Res Rev. 2001;35:36–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Giger RJ, Verhaagen J. Induction of semaphorin(D)III/collapsin-1 mRNA expression in leptomeningeal cells during scar formation. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:614. [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, De Winter F, Giger RJ, Verhaagen J. Role for semaphorin III and its receptor neuropilin-1 in neuronal regeneration and scar formation? Prog Brain Res. 1998a;117:151–170. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, De Winter F, Holtmaat AJ, Verhaagen J. Evidence for a role of the chemorepellent semaphorin III and its receptor neuropilin-1 in the regeneration of primary olfactory axons. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:9962–9976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09962.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Giger RJ, Verhaagen J. Regulation of semaphorin III/collapsin-1 gene expression during peripheral nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 1998c;153:313–327. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Giger RJ, Ruitenberg MJ, Holtmaat AJ, De Wit J, De Winter F, Verhaagen J. Expression of the gene encoding the chemorepellent semaphorin III is induced in the fibroblast component of neural scar tissue formed following injuries of adult but not neonatal CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:143–166. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrausch B, Jung M, Leppert CA, Stuermer CA. Lesion-induced regulation of netrin receptors and modification of netrin-1 expression in the retina of fish and grafted rats. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:350–364. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG, Wei P, Stokes BT. Cellular inflammatory response after spinal cord injury in Sprague-Dawley and Lewis rats. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:443–464. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970120)377:3<443::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabchevsky AG, Streit WJ. Grafting of cultured microglial cells into the lesioned spinal cord of adult rats enhances neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:34–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper J. Semaphorins and their receptors in vertebrates and invertebrates. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovainen CM. Physiological and anatomical studies on large neurons of central nervous system of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). II. Dorsal cells and giant interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1967;30:1024–1042. doi: 10.1152/jn.1967.30.5.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovainen CM. Synaptic interactions of identified nerve cells in the spinal cord of the sea lamprey. J Comp Neurol. 1974;154:189–206. doi: 10.1002/cne.901540206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovainen CM. Regeneration of Müller and Mauthner axons after spinal transection in larval lampreys. J Comp Neurol. 1976;168:545–554. doi: 10.1002/cne.901680407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovainen CM. Neurobiology of lampreys. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:1007–1077. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvig A, Berry M, Barrett LB, Butt A, Logan A. Myelin-, reactive glia-, and scar-derived CNS axon growth inhibitors: expression, receptor signaling, and correlation with axon regeneration. Glia. 2004;46:225–251. doi: 10.1002/glia.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamborn JC, Fiore R, Bagnard D, Kappler J, Kaltschmidt C, Puschel AW. Semaphorin 3A stimulates neurite extension and regulates gene expression in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30923–30926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ME. Mechanisms of functional recovery and regeneration after spinal cord transection in larval sea lamprey. J Physiol (Lond) 1978;277:395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ME. Variability in maps of identified neurons in the sea lamprey spinal cord examined by a wholemount technique. Brain Res. 1979;163:181–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaphorin Nomenclature Committee. Unified nomenclature for the semaphorins/collapsins. Semaphorin Nomenclature Committee [Letter] Cell. 1999;97:551–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Galko MJ, Mirzayan C, Jessell TM, Tessier-Lavigne M. The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell. 1994;78:409–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman MI, Selzer ME. Expression of netrin receptor UNC-5 in lamprey brain; modulation by spinal cord transection. Neurorehab Neural Repair. 2000a;14:49–58. doi: 10.1177/154596830001400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman MI, Selzer ME. In situ hybridization in wholemounted lamprey spinal cord: localization of netrin mRNA expression. J Neurosci Methods. 2000b;104:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman MI, Selzer ME. Semaphorins and their receptors in lamprey CNS: cloning, phylogenetic analysis and developmental changes during metamorphosis. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:115–132. doi: 10.1002/cne.20990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji W, Yee CS, Kuwada JY. Zebrafish semaphorin Z1a collapses specific growth cones and alters their pathway in vivo. Development. 1998;125:1275–1283. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.7.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroga JM, Jones TB, Kigerl KA, McGaughy VM, Popovich PG. Rats and mice exhibit distinct inflammatory reactions after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:223–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.10736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit W. An improved staining method for rat microglial cells using the lectin from Griffonia simplicifolia (GSA I-B4) J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1683–1686. doi: 10.1177/38.11.2212623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ. The role of microglia in regeneration. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1994:S69–70. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85090-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]