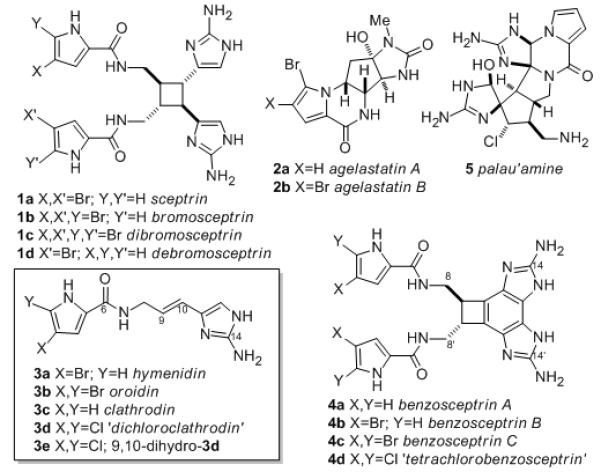

Pyrrole-aminoimidazole alkaloids (PAIs, Figure 1),[1] the characteristic class of compounds found in marine sponges of the genre Agelas, Stylissa, Phakellia, Axinella and Hymeniacedon, have drawn contemporary interest due to their complex structures and examples with potent biological activities.[2]

Figure 1.

Representative PAIs from sponges Agelas spp. and Stylissa, and unnatural chlorinated analogs (3d,e, 4d).

Sceptrin (1a),[3] an intriguing dimeric optically active C2-symmetric cyclobutane, exhibits a broad range of biological activities,[4] including antimicrobial[4a] and antimuscarinic[4b] properties, binding to MreB protein in E. coli,[4c] and inhibition of cell motility in a variety of cancer cell lines.[4d] It is widely accepted that the biosynthesis of complex PAIs begins with three simple building-block PAIs; hymenidin (3a),[5] oroidin (3b)[6] and clathrodin (3c),[7] which are produced naturally in certain sponges. Detailed field experiments support the contention that oroidin (3b) and related molecules, longamide and dispacamide, most likely serve as the primary chemical defenses of Stylissa and Agelas sponges.[8] Sceptrin (1a) is formally derived by [2+2] cycloaddition of 3a, and benzosceptrins A-C (4a-c)[9] are cyclized analogs of 1. The potent antitumor agents, agelastatins A (2a) and B (2b) can be envisioned as a product of enzyme-mediated cyclization-oxidation of 3a,b. The total synthesis of several PAIs, including 3b,[10] 1a[11] and 2,[12] have been reported, culminating in the elegant synthesis of palau’amine (5) by Baran.[13]

Various schemes have been advanced to explain the biosynthesis of 1a,[3] 5,[14] and related PAIs.[15] Most proposals rationalize carbon-carbon bond formation with mechanisms based on the electrophile-nucleophile duality inherent in enamine-imine tautomerism of conjugated 2-aminopyrroles, or concerted electrocyclic reactions that even claim to explain the order of appearance of intermediates.[11] While accounting for the general assembly of PAIs, to date, all two-electron ‘arrow pushing’ schemes fail to address a fundamental discrepancy: no biosynthetic experimental evidence has been advanced to support any of the proposed schemes.

Here, we report the first experimental evidence for the biosynthesis of PAIs by sponges with enzyme-catalyzed conversion of an oroidin analog 3d (dichloroclathrodin) to chlorinated versions of known benzosceptrins[13] and nagelamides. Further, we provide the first evidence of conversion of oroidin (3b) to two known PAIs, benzosceptrin C (4c) and nagelamide H (7a), strong evidence that oroidin is the precusor to these natural products. These successful ‘metabiosynthesis’[17] experiments employ cell-free enzyme extracts obtained from marine sponges, Stylissa caribica, Agelas conifera, and A. sceptrum, carry out C–C bond formation of PAIs through an oxidative mechanism likely involving single-electron transfer (SET) and radical couplings.

Many reported PAI structures share the same carbon-nitrogen framework, but differ only in the number of Br atoms in the pyrrole ring (e.g., 3a,[3] b,c[18] and 2a,b[5]). This suggests that the late-stage enzymatic steps in the biosynthesis of PAIs from 3a-c may be indifferent to halogenation in the pyrrole ring. We exploited this feature to clearly differentiate biosynthesis of PAIs under cell-free conditions using a non-natural chlorinated precursor, dichloroclathrodin (3d), prepared from the known 4,5-dichloropyrrol-2-yl trichloromethyl ketone[19] using a strategy we previously developed for 15N-oroidin.[10c]

Live sponges, Stylissa caribica, Agelas conifera, and A. sceptrum were freshly collected by hand using scuba (−80 ft, Bahamas) and immediately converted to cell-free acetone powders (sc-, ac-, and as-CFP respectively) that contained active enzymes. An aqueous-organic suspension of sc-CFP (0.2 mg/mL protein, Bradford assay) in 1:9 CH3CN–0.1M Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7-9) rapidly consumed 3d (~90% within 30 min, Table 1) and generated several new chlorinated compounds including two with molecular masses about twice that of 3d, and an unstable compound 6. The two major products (Figure 1 and Scheme 1; 4d, [M–H]− m/z 593.13; 7d [M–H]− m/z 718.21) displayed pseudo-molecular ions with isotopic compositions corresponding to Cl4. Improved conversion of 3d was realized by quenching the reaction mixture with bisulfite (100 mM, NaHSO3 aq), conditions that produced a different major product 8 along with 7d. Scaled-up enzyme-catalyzed preparative reactions with 3d provided sufficient quantities of products (~1.0–1.5 mg) to allow complete structure elucidation of 7d and 8 by NMR and MS.

Table 1.

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions of 3d with cell-free preparations from A. conifera (ac), A. sceptrum (as), and S. caribica (sc).[a]

| Entry | Substrate/ enzyme[a] |

% Conversion[b] | Rate, R μMs−1[c] |

pH, conditions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4d | 7d | 8 | |||||

| 1 | 3d | sc | 0 | 0 | – | – | 5 |

| 2 | 3d | sc | 0 | 0 | – | – | 6 |

| 3 | 3d | sc | 52 | 21 | – | 10.3 | 7 |

| 4 | 3d | ac | 19 | 13 | – | 10.2 | 7 |

| 5 | 3d | as | 21 | 10 | – | 10.2 | 7 |

| 6 | 3d | sc | 37 | 60 | – | 10.9 | 8 |

| 7 | 3d | sc | 30 | 55 | – | 10.9 | 9 |

| 8 | 3d | sc | 0 | 13 | 50 | 10.3 | 7[d] |

| 9 | 3d | ac | 5 | 15 | 19 | 5.22 | 7[d] |

| 10 | 3d | sc | 13 | 2 | – | 6.88 | 7, CO[e] |

| 11 | 3d | ac | 0.4 | 0.1 | – | 0.88 | 7, CO[e] |

| 12 | 3d | sc | 7 | 1 | – | 3.00 | 7, F−[f] |

| 13 | 3d | ac | 1.2 | 1.7 | – | 6.56 | 7, F−[f] |

| 14 | 3d | sc | 0 | 0 | – | – | 7, heat[g] |

| 15 | 3d | sc | 3 | 5 | – | 2.44 | 8, Ar[h] |

| 16 | 1a | sc | 0 | 0 | – | – | 7 |

| 17 | 3b | as | 72[i] | 60[i] | – | 11.0 | 7 |

| 18 | 3e | sc | 0 | 0 | – | – | 7 |

[3d]=20 mM in 1:4 CH3CN–0.1M sodium phosphate buffer, 0.2 mg/mL total protein (Bradford assay) of cell-free enzyme preparation (CFP) from either S. caribica (sc), A. conifera (ac), or A. sceptrum (as) (for preparation, see Supporting Information).

Determined by LCMS (UV).

R is an estimated initial rate of consumption of 3d, assuming substrate-saturated conditions.

NaHSO3 aq added during workup (final [HSO3−]=0.1 M).

1 atm, 15 min pre-saturation.

KF (aq, 10 mM), 15 min pre-incubation.

CFP was boiled (100 °C) for 30 min prior to addition of substrate.

1 atm, anaerobic conditions were achieved by purging substrate solution and CFP with Ar for 15 min prior to addition;

Observed products were tetrabrominated natural products 4c and 7a, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Structures of nagelamide H (7a) and chlorinated products 6, 7d, 8 obtained from cell-free metabiosynthesis of 3d and base promoted elimination of 8 to 4d.

Compound 8, C22H20Cl4N10O5S (HR-APCI-TOFMS m/z 675.0015, [M–H]−) showed a new red-shifted chromophore in its UV-vis spectrum (MeOH, λmax 366 nm, ε 4000), in addition to the expected band from dichloropyrrol-2-carboxamide (λmax 274 nm, ε 13600), and strong fluorescence (λex 366 nm; λem 450). The 1H NMR spectrum of 8 (600 MHz, 1.7 mm microcryoprobe, DMSO-d6) showed two relatively unchanged pyrrole NH signals (δ 12.60, s; 12.62, s) suggesting two intact 2,3-dichloropyrrole-2-carboxamide groups. The vinyl protons from the 1,2-disubstituted alkene of 3d were absent and replaced by four contiguously coupled CH signals (COSY) assigned to a 1,2,3,4-tetrasubstituted cyclobutane ring, reminiscent of 1a but lacking symmetry. Interpretation of one-bond sp3 heteronuclear coupling constants, 1JCH, which reflect ring strain,[20] confirmed the four-membered ring (coupled HSQC of 8: 1JCH 136 Hz (C9), 134 (C9′), 148 (C10), 138 (C10′)); c.f. 1a, 1JCH 135 Hz (C9/9′), 136 (C10/10′)). Interpretation of COSY and HMBC data allowed connection of the partial structures (see Supporting Information), including key HMBC correlations from both H9′ (δ 1.78) and H10′ (δ 3.35) to C11′ (δ 86.4) and from H10 (δ 3.58) to C12 (δ 116.0). NOESY data were used to assign the relative configuration of the cyclobutane ring. NOEs observed between H9 (δ 2.54), H10, and H10′ supported a cis ring fusion, while correlations between both H2-8 protons (δ 2.78, 3.00) and H9′ and between both H2-8′ protons (δ 3.17, 3.25) and H9 supported a trans orientation for the dichloropyrrol-2-carboxamide side chains, consistent with known cyclobutane-containing PAI natural products.[3]

Comparing the formulas of 6 and 8, it is apparent that the latter is the bisulfite addition product of the former captured from a reactive intermediate in the reaction pathway (Table 1, entries 3 vs. 8). Treatment of 8 with alkali (NaOH, aq. 23 °C) resulted in elimination of H2SO3 to give the postulated intermediate i (Scheme 1), with loss of both the red-shifted chromophore and its associated fluorescence, and transformation into 4d, the Cl4-derivative of benzosceptrin A (4a).[9] The 1H NMR spectrum of 4d is almost identical to that of the natural product benzosceptrin B (4b). We observed that sceptrin (1a), itself, is not a viable substrate for the enzyme-catalyzed oxidation; exposure of 1a to sc-CFP produced no 4b or 7a and returned only starting material which suggests that sceptrin is not an intermediate in the biosynthesis of benzosceptrins, nor is it isomerized under these conditions to ageliferin.

The second, more hydrophobic product 7d has a formula C24H24Cl4N11O5S (HR-APCI-TOFMS m/z 718.0439, [M–H]−) corresponding to four-electron oxidative dimerization of dichloroclathrodin (3d) and addition of the elements of taurine, NH2(CH2)2)SO3H.21 Analysis of NMR data (800 MHz, d6-DMSO; 1H NMR, COSY, HSQC, HMBC) revealed the structure of 7d as the chlorinated analog of nagelamide H (7a).[22]

Finally, natural oroidin (3b) was also converted to known PAI natural products under similar conditions. Cell-free enzyme preparations of A. sceptrum, which contains 1a but lacks 3b at detectable concentrations (LCMS), rapidly oxidized 3b to give the known natural products benzosceptrin C (4c) and nagelamide H (7a) (Table 1, entry 17 and Supporting Information). This is the first experimental evidence of formation of complex PAIs from the widely-presumed precursor oroidin.[23]

As dimerization of hymenidin (3a) to benzosceptrin B (4b) is a net four-electron oxidation (formal loss of 2H2), we propose that all conversions of 3 to 1,2,5-8, involve discrete enzyme-catalyzed reactions, possibly involving one or more oxido-reductases,[24] as supported by the following lines of evidence. Optimal conversion was found at pH ≥ 7 (Table 1, entries 1-7). Boiled sc-CFP (100 °C) resulted in loss of activity and no conversion of 3d (Table 1, entry 14). Similarly, activity was greatly attenuated when incubation of 3d was carried out under an atmosphere of CO (1 atm, Table 1, entries 10,11) or in the presence of fluoride ion (10 mM, KF aq, Table 1, entries 12,13), conditions known to inhibit cytochrome oxidases. Addition of H2O2 (50 μM) to the enzyme incubation made no change, however incubation of 3d with sc-CFP under anaerobic conditions also led to significantly reduced yields of 4d and 7d (Table 1, entry 15). Collectively, these data suggest that O2 is the terminal oxidant. Ultracentrifugation of the crude enzyme preparation (10 kDa MWCO) resulted in retention of all activity (conversion of 3d into 4d/7d) in the fraction >10 kDa, (see Figure S3); results that support enzyme-mediated conversion of 3d.

The observed conversions of dichloroclathrodin (3d) appear to be paired to oxido-reductases associated with Stylissa and Agelas sponges. Replacement of sponge-CFPs with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) gave no 4d or 7d and only produced complex mixtures of unidentifiable products. Furthermore, 9,10-dihydrodichloroclathrodin (3e, Table 1, entry 18), prepared in a similar manner to 3d, does not undergo oxidation under the reaction conditions, consistent with requirements for a π-electron-rich donor-substrate and stabilization of radical-cation intermediates through delocalization.

The enzyme-catalyzed dimerization of dichloroclathrodin (3d) is specifically linked to PAI-producing sponges. Cell-free enzyme preparations of several PAI-producing Agelas sponges all converted 3d to 4d/7d, while incubation of 3d similarly prepared extracts of five co-occurring sponges that do not produce PAIs failed to generate 4d/7d or oxidize 3d at all (Table S1).

We detected appreciable concentrations of 3b in both A. conifera and S. caribica, but not in A. sceptrum (Figure S1). Neither S. caribica or A. conifera from the Caribbean appear to contain natural benzosceptrins (4a-c); these natural products were described only from sponges collected in the Mediterranean Sea and Pacific Ocean. Yet, remarkably, the chlorinated analogs of the latter natural products are rapidly formed when 3d is exposed to cell-free preparations of the sponges A. conifera and S. caribica from the Caribbean Sea, revealing the permissive nature of the sponge oxido-reductases. Cell-free enzyme preparations of both sponges unleash competent enzymes that catalyze oxidative couplings and give rise to the same products 4d and 7d-8 found in sponge of the same genus from different geographic locations. Disruption of the living sponge tissue and cellular structure, apparently, liberates enzymes that retain their oxidative capacity to carry out oxidative biosynthesis of PAIs, albeit without the level of control that presumably operates within intact sponge cells.

We hypothesize benzosceptrins, nagelamides, and 6–8, arise from sequential SET that result in four-electron oxidation of 3a-c. By association, it is also likely, that biosynthesis of many other PAIs are mediated by orchestrated enzymatic SET (Scheme 2) that initiate formation resonance-stabilized radical-cation intermediates and subsequent reactions.[25] We propose that the biosynthesis of PAIs proceeds through intermediates that partition between at least two discrete, enzyme-mediated pathways (Scheme 2) leading to oxidized products 4d, 6 and 8 or redox-neutral products (e.g., sceptrin 1a) with respect to the starting materials. In the case of 1a, SET from the π-rich conjugated vinyl-2-amino-imidazole of 3a to the metal center of the oxido-reductase generates a radical-cation (i) that adds to a neutral molecule of 3a, with loss of H+ to form the first C–C bond of the pre-cyclobutane radical intermediate (ii) followed by cyclization to iii (Scheme 2, path a). Subsequent SET reduction by an electron carrier provides 1a with net-zero electron transfer. Thus, 1a is formed through a ‘cryptic’ oxidative mechanism. Compounds 4d, 6 and 8 arise from a different path b, possibly through cationic intermediate iv, and nucleophilic capture (H2O or HSO3−) with net 4-electron oxidation. Elimination of HX gives 4d after tautomerism (see Scheme 1).[26] The nagelamide H analog 7d may emerge from further oxidation at the imidazole ring of ii (hydroxylationtautomerism, not shown) and nucleophilic capture of an incipient 2-iminoimidazolidinone by taurine.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanisms for enzyme-catalyed SET of 3d and cyclization to 1a (path a) or 6/8 (path b).

Even numbers of SET oxidation steps could, conceivably, give rise to the even-electron cationic species, including acyliminium ions that have been implicated in the biosynthesis of agelastatins,[12b] phakellins, palaua’mine and other PAIs.[15] High-energy radicalcation intermediates would better explain the formation of the ring-strained PAI alkaloids; e.g., cyclobutanes (1,4,6 and 8) and trans-bicyclo[3.3.0]octane (5) as the enthalpic cost is paid by reduction of the terminal oxidant, O2. An important feature of the SET hypothesis is its compatibility with many late-stage two-electron C–C bond-forming reactions currently favored in PAI biosynthetic proposals. An additional attractive feature of odd-electron pathways from 3 is accessibility to reactive intermediates (radical) with sufficiently high free energy, to bypass the kinetic barriers that disfavor ionic or concerted mechanisms, (e.g., thermal [2+2] cycloaddition or cycloreversion[27]), without the need to invoke unlikely excited states or violations of orbital symmetry rules.[26]

The evidence we present (Table 1, entries 10-13) strongly argues for a metalloenzyme catalyzed C–C bond formation in PAI biosynthesis. The modular nature of PAI biosynthesis is now succinctly explained by single-electron processes, not unlike the modular biosynthesis of lignans that also proceed through radical phenolic couplings catalyzed by metalloenzymes. Fe-porphyrin oxidoreductases are known to carry out lignan biosynthesis,[28] for example conversion of coniferyl alcohol to pineol, with dioxygen (O2) as terminal oxidant. We favor the latter in PAI biosynthesis, although we cannot rule out the possibility that other metalloenzymes, for example laccases, are involved.

Several details of the enzyme-mediated formation of PAIs remain to be elucidated; for example, the mechanism by which optical activity is induced. Compounds 4d, 7d, and 8 appear to have lower optical activity than the natural products,[29] however, as in lignan biosynthesis, asymmetry may be induced by the action of dirigent proteins[30] that are coupled with oxidases to control stereochemistry, a property that may be disrupted in cell-free preparations. The sub-cellular location, structural-ordering and compartmentalization of the biosynthetic enzymes, and additional oxidative steps required to generate higher order PAIs including palau’amine and ‘tetrameric’ members – and purification of these oxidoreductase(s) – and other aspects of SET oxidation in the biosynthesis of PAIs are the subjects of ongoing investigations in our laboratories.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated cell-free enzymatic conversion of oroidin (3b) and an oroidin-like precursor 3d to natural products benzosceptrin C (4c), nagelamide H (7a), and their tetrachloro-analogs (4d) and (7d), respectively. The results implicate oxidoreductase-like activity in the biosynthesis of PAIs in marine sponges through single-electron transfer, and we suggest an SET pathway that may explain the origin of sceptrin (1a) and related oroidin-derived dimeric PAIs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding for this work from NIH (GM052964) and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NIH/NCI T32 CA009523) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank J.J. LaClair and M. Burkart for help with fluorescence spectra, B. Morinaka and Y. Su (UCSD) for NMR and HRMS measurements, respectively. We are grateful to J. Pawlik (UNC Wilmington), and the captain and crew of the RV Cape Hatteras for logistical support during collecting expeditions and in-field assays.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. E. Paige Stout, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science, University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA)

Dr. Yong-Gang Wang, Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University P.O. Box 30012, College Station, TX 77842 (USA)

Dr. Daniel Romo, Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University P.O. Box 30012, College Station, TX 77842 (USA)

Dr. Tadeusz F. Molinski, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science, University of California, San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA).

References

- [1].For clarity, each PAI is drawn as the free base and a discrete tautomer, although most are isolated as salts, and counterions and tautomer equilibria may vary with structure.

- [2].Aiello A, Fattorusso E, Menna M, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Fattorusso E. Modern Alkaloids. In: Taglialatela-Scafati O, editor. Structure, Isolation, Synthesis, and Biology. WILEY-VCH; Darmstadt: 2008. The possibility that PAIs are the products of bacterial consortia has not been excluded.

- [3].Walker RP, Faulkner DJ, Van Engen D, Clardy J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:6772–6773. [Google Scholar]

- [4] a).Bernan VS, Roll DM, Ireland CM, Greenstein M, Maiese WM, Steinberg DA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1993;32:539–550. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rosa R, Silva W, de Motta GE, Rodríguez AD, Morales JJ, Ortiz M. doi: 10.1007/BF02118426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Rodríguez AD, Lear MJ, Clair J.J. La. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7256–7258. doi: 10.1021/ja7114019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cipres A, O’Malley DP, Li K, Finlay D, Baran PS, Vuori K. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:195–202. doi: 10.1021/cb900240k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kobayashi J, Ohizumi Y, Nakamura H, Hirata Y. Experientia. 1986;42:1176–1177. doi: 10.1007/BF01941300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6] a).Forenza S, Minale L, Riccio R, Fattorusso E. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1971;18:1129–1130. [Google Scholar]; b) Garcia EE, Benjamin LE, Fryer RI. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1973:78–79. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Morales JJ, Rodriguez AD. J. Nat. Prod. 1991;54:629–631. doi: 10.1021/np50077a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lindel T, Hoffmann J, Hochgürtel M, Pawlik JR. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000;26:1477–1496. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Appenzeller J, Tilvi S, Martin MT, Gallard JF, Elbitar H, Dau ETH, Debitus C, Laurent D, Moriou C, Al-Mourabit A. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4874–4877. doi: 10.1021/ol901946h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10] a).Lindel T, Hochgürtel M. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2806–2809. doi: 10.1021/jo991395b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bhandari MR, Sivappa R, Lovely CJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1535–1538. doi: 10.1021/ol9001762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang Y, Morinaka BI, Reyes JCP, Wolff JH, Molinski TF, Romo D. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:428–434. doi: 10.1021/np900638e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11] a).Baran PS, O’Malley D, Zografos A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2674–2677. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004;116:2728–2731. [Google Scholar]; b) Baran PS, Zografos L, O’Malley D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3726–3727. doi: 10.1021/ja049648s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Birman VB, Jiang XT. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2369–2371. doi: 10.1021/ol049283g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12] a).Stein D, Anderson GT, Chase CE, Koh YH, Weinreb SM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9574–9579. Movassaghi M, Siegel DS, Han S. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:561–566. doi: 10.1039/c0sc00351d. For a comprehensive review of other agelastatin A syntheses, see Weinreb SM. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:931–948. doi: 10.1039/b700206h.

- [13].Seiple IB, Su S, Young IS, Lewis CA, Yamaguchi J, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:1095–1098. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010;122:1113–1116. [Google Scholar]

- [14] a).Kinnel RB, Gehrken HP, Swali R, Skoropowski G, Scheuer PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3281–3286. [Google Scholar]; b) Feldman KS, Nuriye AY. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4532–4535. doi: 10.1021/ol1018322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ma Z. Zhiqiang, Lu J, Wang X, Chen C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:427–429. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02214d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15] a).Hoffmann H, Lindel T. Synthesis. 2003;12:1753–1783. [Google Scholar]; b) Al-Mourabit A, Potier P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:237–243. [Google Scholar]; c) Köck M, Grube A, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6586–6594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Al-Mourabit A, Zancanella M, Tilvi S, Romo D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:1229–1260. doi: 10.1039/c0np00013b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].For a bio-inspired strategy to phakellin, see Foley LH, Büechi G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:1776–1777. For a recent bioinspired approach to palau’amine see Li Q, Hurley P, Ding H, Roberts AG, Akella R, Harran PG. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5909–5919. doi: 10.1021/jo900755r.

- [17].The term ‘meta-biosynthesis’ is coined here to define cell-free, enzymatic reactions conducted on non-natural substrates to give natural product analogs.

- [18] a).Köck M, Assmann MZ. Naturforsch. 2002;57c:157–160. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-1-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keifer PA, Schwartz RE, Koker MES, Hughes RG, Jr., Rittschof D, Rinehart KL. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:2965–2975. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bélanger P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:2505–2508. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dalisay DS, Morinaka BI, Skepper CK, Molinski TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7552–7553. doi: 10.1021/ja9024929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Taurine is an osmolyte commonly found in sponges high concentrations and, evidently, entrained in our CFP preparations.

- [22].Endo T, Tsuda M, Okada T, Mitsuhashi S, Shima H, Kikuchi K, Mikami Y, Fromont J, Kobayashi J. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1262–1267. doi: 10.1021/np034077n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Redox-neutral conversion of 3b to dibromosceptrin (1c) was not detected in this experiment, a result possibly due to dysregulation of electron-donor/acceptors in disrupted cell-free enzyme preparations. High conversions of 3b/d into benzosceptrins (4c/d) and nagelamides H (7a/d) were also achieved with CFPs from other PAI-producing Caribbean sponges (Table S1).

- [24].Peroxidase-promoted radical pairings generate C–C bonds without incorporation of oxygen; Kutchan TM, Chou WM. Plant J. 1998;15:289–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00220.x. Nielsen KA, Lindberg-Møller BL. In: Cytochrome P450. Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. Kluwer; 2005. pp. 553–574.

- [25].There is no a priori reason to assume the involvement radical-cation intermediates over radical anions except for abundant precedence of peroxidases in C–C coupling reactions, relatively low oxidation potential of vinyl-2-aminoimidazoles, and the experimental evidence presented herein. Efficient in vitro catalytic redox-neutral synthesis of cyclobutanes by radical anion coupling has been demonstrated. Du J, Yoon TP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14604–14605. doi: 10.1021/ja903732v.

- [26].For example, photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition of 3b, which requires an S1 excited state and intersystem crossing to T1, is unlikely in Stylissa caribica, a sponge that biosynthesizes 1b but lives in subdued light conditions, at depths no less than −25 m. In any case, failure of photochemical dimerization of 3b to 1a under laboratory conditions is likely due to other factors.

- [27].Baran proposes that 1a is biosynthetically transformed to the isomeric ageliferin via thermal cyclobutane ring opening of 1a to a diradical which re-closes to the cyclohexene (See Ref. 15b). Al-Mourabit and coworkers favor an alternative even-electron pathway from 3b to 4b. See Ref. 9.

- [28].Bao W, O’Malley DM, Sederoff RR. Science. 1993;260:672–674. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5108.672. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this analogy.

- [29].Enantio-heterogeneity of PAIs is not unexpected. For example, both optical antipodes of the natural product, phakellin, have been reported, see: Burkholder PR, Sharma GM. Lloydia. 1969;32:466–483. Pettit GR, McNulty J, Herald DL, Doubek DL, Chapuis J-C, Schmidt JM, Tackett LP, Boyd MR. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:180–183. doi: 10.1021/np9606106.

- [30].Davin LB, Wang H-B, Crowell AL, Bedgar DL, Martin DM, Sarkanen S, Lewis NG. Science. 1997;275:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.