Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite an emphasis on pain management in palliative care, pain continues to be a common problem for individuals with advanced cancer. Many of those affected are older due to the disproportionate incidence of cancer in this age group. There remains little understanding of how older patients and their family caregivers perceive patients’ cancer-related pain, despite its significance for pain management in the home setting.

OBJECTIVES:

To explore and describe the cancer pain perceptions and experiences of older adults with advanced cancer and their family caregivers.

METHODS:

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to describe and interpret data collected from semistructured interviews with 18 patients (≥65 years of age) with advanced cancer receiving palliative care at home and their family caregivers.

RESULTS:

The main category ‘Experiencing cancer pain’ incorporated three themes. The theme ‘Feeling cancer pain’ included the sensory aspects of the pain, its origin and meanings attributed to the pain. A second theme, ‘Reacting to cancer pain’, included patients’ and family caregivers’ behavioural, cognitive (ie, attitudes, beliefs and control) and emotional responses to the pain. A third theme, ‘Living with cancer pain’ incorporated individual and social-relational changes that resulted from living with cancer pain.

CONCLUSIONS:

The findings provide an awareness of cancer pain experienced by older patients and their family caregivers within the wider context of ongoing relationships, increased patient morbidity and other losses common in the aged.

Keywords: Aging, Cancer, Caregiver, Pain, Palliative, Relationship

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Même si on accorde beaucoup d’importance à la gestion de la douleur en soins palliatifs, celle-ci continue de représenter un problème courant chez les personnes ayant un cancer avancé. Nombre d’entre elles sont âgées en raison de l’incidence disproportionnée de cancers au sein de ce groupe. On ne sait pas grand-chose de la façon dont les patients âgés et leurs aidants familiaux perçoivent la douleur liée au cancer des patients, malgré son importance dans le cadre de la gestion de la douleur à domicile.

OBJECTIFS :

Explorer et décrire les perceptions et les expériences relatives aux douleurs attribuables au cancer des personnes âgées atteintes d’un cancer avancé et de leurs aidants familiaux.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont privilégié une approche descriptive qualitative pour décrire et interpréter les données colligées dans le cadre d’une entrevue semi-structurée auprès de 18 patients (de 65 ans ou plus), ayant un cancer avancé et recevant des soins palliatifs à domicile, et de leurs aidants familiaux.

RÉSULTATS :

La principale catégorie, « Éprouver la douleur liée au cancer », se déclinait en trois thèmes. Le thème « Ressentir la douleur liée au cancer » incluait les aspects sensoriels de la douleur, ses origines et les significations qu’on lui attribue. Un deuxième thème, « Réagir à la douleur liée au cancer », incluait les réactions comportementales, cognitives (les attitudes, les croyances et le contrôle) et affectives des patients et des aidants familiaux à la douleur. Un troisième thème, « Vivre avec la douleur liée au cancer », intégrait les changements individuels et sociaux qui découlaient d’une vie avec la douleur liée au cancer.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les observations permettent de faire connaître la douleur liée au cancer que vivent les patients âgés et leurs aidants familiaux dans le contexte plus vaste de relations suivies, de la morbidité accrue des patients et d’autres pertes courantes chez les personnes âgées.

Cancer has been referred to as a ‘disease of old age’ because of the high incidence of cancer in later life and the mortality rates due to the disease (1). Although advances in screening and treatments have led to increasing numbers of individuals surviving cancer, cancer remains one of the main causes of death in most Western countries (2). Older individuals are particularly affected because they are more likely to be diagnosed in the later stages of the disease, when treatment is less successful and symptoms are more prevalent (3). Although symptoms may vary depending on the type of cancer and its stage, pain is typically a symptom in the advanced stages (4). At this stage of the disease, the focus of care is usually palliative, with an emphasis on the prevention and relief of symptoms and support to maximize quality of life for patients and their families (5). However, pain continues to be a common and distressing symptom, despite pain management being a central focus of palliative care and guidelines for the management of cancer pain (5,6). Estimates suggest that as many as 60% to 80% of individuals with recurrent or metastatic cancer experience pain (7). Among older patients, cancer pain, similar to other types of pain, tends to go unrecognized and undertreated (7–9). A comprehensive understanding of pain and its management in older patients with advanced cancer is fundamental for directing efforts toward addressing this discrepancy.

Cancer pain in advanced disease is complex. Chronic cancer pain is generally the result of underlying damage caused by cancer, its progression and treatment. The characteristics of the pain vary depending on the type, categorized as nociceptive (visceral or somatic) and neuropathic (10). Acute episodes of severe pain referred to as ‘breakthrough’ or ‘episodic’ pain are also a regular occurrence (11). It is not unusual, therefore, for patients to experience multiple types of pain that may require different management interventions (12). In older individuals, the higher incidence of comorbidities, age-related declines in functioning and associated symptoms can further complicate cancer pain and its management (13–15). Adding to the complexity is the recognition that the experience of pain is not merely a sensory event, but is multifaceted, comprising sensory, affective and evaluative components (16). In the context of advanced disease, Cohen and Mount (17) make note of the bidirectional relationship between the individual’s cognitive, psychological, social and spiritual state and the experience of pain, and the effects of pain on all aspects of his/her life. Indeed, the belief that pain can emanate from both physical sources and nonphysical sources (psychological, spiritual and interpersonal) is central to the concept of total pain, put forth by Dame Cicely Saunders, founder of the modern hospice (18). This nonphysical source of pain derives from feelings of helplessness, being dependent on others and having difficulty in reshaping relationships, and has been described by terminally ill older patients as creating the worst suffering (19). Therefore, the experience of pain has to be understood within this broader framework.

A shift toward care in the community for individuals with advanced cancer, and a preference by patients to die at home (20), have meant that home care is an increasing reality. Cancer pain management is now an integral part of family caregiving (hereafter caregiver) (21). In this context, in which contact with health care professionals is more limited, there is reliance on both patients and their family members to assume various responsibilities with respect to pain management (22). Although patients and caregivers show a willingness to be involved in pain management, it is identified as one of the most challenging aspects of care and many believe that they do not have control over cancer pain (23–25). The adverse effects of cancer pain on patients’ quality of life have been well documented (17,26). For older patients with cancer, unrelieved pain can affect functioning, increase cognitive impairment and depression, which in turn can influence the severity of pain and make management more challenging (27). While less attention has been devoted to the effects of patients’ pain on caregivers, there is increasing evidence to indicate that witnessing a family member in pain can negatively affect the caregiver (23,28). Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of focusing attention on the context of care and how cancer pain is experienced and managed within the caregiver-patient dyad.

In the literature examining cancer-related pain and pain more generally in older individuals, numerous barriers to effective management of pain have been identified at the organizational, health care provider, and individual patient and caregiver levels (29–33). At the individual level, patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes toward pain and its treatment can influence management – for instance, the belief that pain must be endured, or that it is a natural part of aging (33). Specific to cancer are beliefs about cancer pain and its treatment, including concerns about side effects, drug tolerance and dependence on analgesics, such as opioids, which are identified as major reasons why there is a reluctance to use them (30,31). Pertinent to advanced cancer are beliefs about the inevitability of pain with cancer and the existential significance of pain as a sign of impending death in advanced cancer, which may give rise to denial of the existence or significance of the symptom (28,34,35). Furthermore, reticence to report pain for fear of distracting clinicians (31) and patients’ concerns about being a burden to family members (36) can limit pain communication and impede assessment.

In sum, the literature indicates that cancer pain in advanced disease is multifaceted and can adversely affect the lives of patients and their caregivers. Changes associated with aging have the potential to further impact this experience. Despite these findings and the high prevalence of cancer and cancer pain in older individuals, there is a dearth of literature aimed at gaining a comprehensive understanding of cancer pain from the perspectives of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. These perspectives are important for addressing the unique needs of these individuals and for identifying potential factors that contribute to poor cancer pain management. To date, researchers have explored patients’ or caregivers’ perspectives on cancer pain but in isolation of one another (19,21,37–40). Few have incorporated both perspectives (41,42), and these studies were not specific to older patients with advanced cancer. The aim of the present study, therefore, was to describe the cancer pain perceptions and experiences of older patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care and their caregivers. The research is part of a larger investigation examining pain assessment and management in older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.

METHODS

Design

A qualitative descriptive approach with thematic analysis was used to describe and interpret data collected from semistructured interviews with participants (43,44). Congruent with the naturalistic paradigm, an inductive latent approach was used whereby analysis of the text extends beyond the manifest content to interpretation of the content and context (44,45). This approach enabled the exploration of participants’ experiences, understandings, meanings and intentions with regard to cancer pain.

Participants and setting

Following ethics approval, participants were recruited through an organization that coordinates home care services across a large urban area. To gain a more complete understanding of the phenomenon of interest from varying perspectives, the sample was purposely chosen to include different types of patient-caregiver relationships (spouse, sibling and adult child), and patient and caregiver sex.

Eligibility criteria were: diagnosed with advanced cancer (stage III or IV); 65 years of age or older; experienced cancer pain for at least one month; determined as cognitively able to provide consent and reliable information, and well enough to participate (as determined by each patients’ nurse case manager); English or French speaking; known to palliative care services; and cared for at home. The inclusion criteria for caregivers were: providing the majority of care to the patient at home; and English or French speaking.

Participants comprised a purposeful convenience sample of 18 patients and 15 caregivers. In three cases, a caregiver was not interviewed. Of these, two caregivers were not available, and one patient did not want her caregivers contacted. The patient interview data were included in these instances because it provided a valuable perspective on how pain was managed under these circumstances.

As shown in Table 1, patients’ ages ranged from 65 to 93 years. There were roughly equal numbers of male (n=8) and female patients (n=10) but more female (n=11) than male (n=4) caregivers. Self-identified ethnic/cultural background indicated that the majority were Canadians of European descendancy, although the sample also included first-generation Italian, English, Dutch and Haitian participants. Most interviews were conducted in English. Only three patient and caregiver interviews were conducted in French. Patients had various types of advanced cancers (Table 1), although the primary cancer location tended to be breast for women. In fully describing the sample, an assessment of patients’ functional status and current pain rating was included. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) was used by the interviewers to provide a measure of patients’ physical functioning based on discussion with the patient (46). The PPS includes factors that reflect physical decline in terminal illness: ambulation; activity and evidence of disease; self-care, intake and level of consciousness. Categories on the PPS range from fully ambulatory and healthy (100%) to death (0%) in 10% increments of decline. The median PPS score of 60% indicated that most patients required some level of assistance with daily activities. Pain ratings were obtained at the time of the interview using the pain item from the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) (47). The ESAS is a tool routinely used by the organization from which recruitment occurred. The ESAS comprises a 10-point scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10. Pain ratings taken at the time of the interview ranged from 0 to 10, with a median rating of 4.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Patient (n=18) | Caregiver (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 78 | 70 |

| Range | 65–93 | 34–86 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8 | 4 |

| Female | 10 | 11 |

| Cultural/ethnic background (self-identified) | ||

| Canadian | 11 | 9 |

| French Canadian | 3 | 3 |

| European | 3 | 2 |

| Haitian | 1 | 1 |

| Relationship between patient and caregiver | ||

| Partner | 11 | |

| Parent/adult child | 3 | |

| Sibling | 1 | |

| Residing with the patient | 13 | |

| Primary cancer site | ||

| Breast | 5 | |

| Genitourinary | 4 | |

| Digestive/gastrointestinal | 4 | |

| Respiratory/thoracic | 3 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| PPS, %, range (median) | 90–40 (60) | |

| ESAS pain score, range (median) | 0–10 (4) |

Data presented as n unless otherwise indicated. ESAS Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale; PPS Palliative Performance Scale

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with patients and caregivers separately in all but one case, in which they requested to be interviewed together. The semistructured interview format was used with broad open-ended questions for flexibility and to enable participants to discuss their experiences; for instance, “Tell me about your pain?”. Probing was used to elicit a more detailed response or information, eg, “How do you typically respond when you are in pain?”. An additional question concerning how pain had affected the relationship was included because this was identified as an issue in earlier interviews. The present article reports on the experience of pain, but the following lines of inquiry were explored as part of the larger study: perceptions of pain, pain management and challenges to pain management in the home environment. On average, the interviews took slightly longer than 1 h and were audio-recorded to facilitate analysis. The first (CM) and fourth (KK) authors conducted the majority of the interviews. A French-speaking graduate nurse conducted the French-language interviews. All interviewers were experienced registered nurses with experience in palliative care practice and research. Field notes were made by interviewers after each interview to capture their initial reactions and interpretations.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interview data were transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo 8 qualitative analysis software program (QSR International, USA) to assist with the organization of the data. To ensure the transcription was accurate, the audio-recordings were compared with the transcribed data. Data collection and analysis were iterative.

Data analysis was conducted by the first author (CM). Consistent with thematic analysis using a latent inductive approach (43,44), each transcript was read and reread in its entirety to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences. The transcripts were also read within the context of the dyadic patient-caregiver relationship. Preliminary observations and interpretations in the form of notes, patterns and associations were made during this process. Codes representing meaningful units related to the focus of the research were identified to capture the latent content of the data. Analysis of earlier transcripts was used to guide analysis of successive transcripts, during which new codes were added, and existing codes modified, developed and combined. Once all of the transcripts had been coded, a second researcher/interviewer (KK) also analyzed and coded the data independently. The codes were discussed between the researchers (CM and KK) and general consensus was reached. Discrepancies were resolved by re-examining the transcripts and considering the context and transcript in its entirety. Preliminary themes were developed at this stage. An audit trail of decisions was maintained throughout the analysis process. To ensure that the codes and themes represented participants’ experiences, they were reviewed by a research team (CM, TH, ML, KK) comprising individuals with varied experience, academic and clinical backgrounds (nursing, psychology, gerontology and oncology).

RESULTS

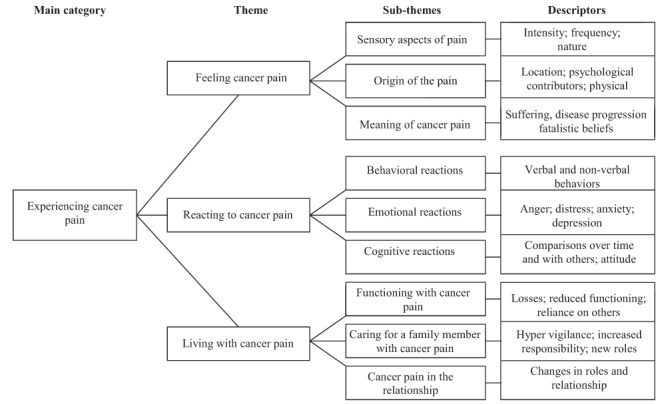

Experiencing cancer pain represented the totality of the pain as experienced by the patient and their caregiver. Within the major overriding category of ‘Experiencing cancer pain’, there were three main themes: ‘Feeling cancer pain’, ‘Reacting to cancer pain’ and ‘Living with cancer pain’ and, within each theme, a number of subthemes (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Themes, subthemes and descriptors representing the main category ‘Experiencing the pain’

Feeling cancer pain

The theme ‘Feeling cancer pain’ incorporated the sensory aspects of pain (characteristics, intensity, temporality and frequency), its origin (location, cause and nature) and the meaning attributed to cancer pain.

Sensory aspects of pain:

For patients, pain was described in terms of its physical sensation and presence, using descriptors such as ‘stabbing’, ‘burning’, ‘throbbing’ and ‘sharp’ to signify the acuteness of the sensation. Adjectives such as ‘excruciating’ and ‘intolerable’ conveyed the intensity of the pain, endured by almost all patients at some point during their cancer experience. For the majority of patients, this was infrequent or brief in duration because of intervention. However, two patients were still experiencing severe levels of pain indicated by a rating of 7 and 10 on the ESAS. Other descriptors such as ‘sore’, ‘ache’, ‘niggle’ and ‘cramp’ were used to characterize less acute types of pain that were constant or more frequent in nature. Although three patients indicated that their pain level was 0 at the time of the interview, most stated that they were living with pain on a daily basis, as the following comment illustrates:

I will say, I always have pain here [points to the area], I would say that it’s 4 [ESAS rating], but at some point, it’s as if I was stabbed on the side. That hurting is awful.

(P19)

Patients and caregivers described the pain in terms of its frequency (ie, ‘constant’, ‘frequent’ and ‘now and again’) and temporal characteristics. They often made note of when the pain occurred (ie, ‘at night’, ‘in the morning’) and the pattern of change in pain during episodes (ie, ‘increasing’, ‘intermittent’).

Origin of the pain:

Patients and caregivers referred to the location of the patient’s pain in terms of the sensation being localized to the primary cancer site or areas of metastases, although few made reference to pain in only one area; usually two or three different sites were identified. Both caregivers and patients had difficulty differentiating between the origin of the pain as being cancer- or treatment-related. Furthermore, comorbidities with other types of pain (ie, arthritis, diabetic neuropathy, hernia and lupus) and symptoms (ie, constipation, swelling, muscular pains and stomach problems) made it difficult sometimes to distinguish between the type and origin of the pain, as the following patient response illustrates:

I have a lot of arthritis too so you know some of it may be arthritis related who knows…I don’t think you can separate them out one from the other.

(P5)

Several patients indicated that they had delayed seeking treatment or receiving a diagnosis of cancer because the pain was attributed to another cause rather than cancer.

The origin of the pain was not purely at a physical sensory level, as the following response from a caregiver describing her husband’s pain shows:

I don’t really know if he suffers from cancer pain yet. Besides suffering more from the pain of .. from the psychic pain. Knowing he has .. cancer. Serious cancer.

(FCG15)

Apart from the pain of cancer, several patients talked of the pain associated with losses:

And there is another pain that no one really talks about. It is the mental pain……The anguish of not being able to, of not being able to do something. Finding out that you can’t do it. And that raises a certain...pain whether it is pain or psychological. It makes a big difference.

(P15)

The pain for caregivers originated from witnessing and sharing in the experience. Some caregivers’ responses to patients’ pain indicated that they perceived themselves as experiencing more distress from the pain experience than did patients. Commenting on his wife’s pain, one caregiver stated:

I think that very frequently, it is as hard or harder for me than for her because I know that she is usually very tough on her body then when she says that she has pain, I know that she has a lot of pain.

(FCG20)

Patients also commented on the shared experience. Talking about her daughter, one patient said:

She will take that in heart [repeats three times]…The force of staying with me. We can see that she participates in my pain.

(P3)

Meaning of cancer pain:

Pain had different meanings for participants and attempts were made to understand both the origin and the meaning:

I try to identify where is the pain to see if it’s in the same spot, if so, well I’m not too worried but if it’s a new pain, then there is something else to think about, that may be there is another thing which is developing.

(P16)

Pain became a constant reminder of the presence of cancer for participants. Consequently, increasing levels of pain attributed to cancer often signified that the disease was progressing. There was also a sense of fatality that pain was a part of dying. Commenting on the meaning of cancer pain, one caregiver stated:

I don’t like to see her in pain …but.. you have to accept that. That is part of dying.

(FCG16)

Because of this association there was an expectation of increased levels of pain as the end of life neared, as another patient conveyed:

I am in my final stage. I cannot say but when you have this illness we cannot expect better. It is all that I can say.

(P18)

Participants’ comments suggested that unbearable and intense levels of pain were analogous to suffering. As one patient expressed:

I suffered a lot at the beginning. I had a lot of pain.

(P20)

Reacting to cancer pain

The theme ‘reacting to cancer pain’ encompassed participants’ reactions in response to patient’s pain. Included were three subthemes that captured behaviours, cognitions and emotions related to expressions of pain and coping.

Behavioural reactions:

When the pain was intense, responses included both verbal (ie, shouting, asking for help and groaning) and non-verbal behaviours (ie, holding or massaging the painful area, grimacing). Behaviours mentioned most often were aimed at alleviating the pain, and included taking medications, restricting movement and lying down. Caregivers tended to respond by trying to assist the patient to relieve the pain, including in many instances encouraging or administering medications.

Cognitive reactions:

Cognitive reactions comprised beliefs important in evaluating and coping with the pain. Evaluations of the pain were made in terms of comparisons over the cancer trajectory, in relation to others with cancer, and within the context of other types of pain from comorbidities. These evaluative comparisons helped in rationalizing the level of pain and were important for coping. One patient whose wife also had advanced cancer compared his pain with hers:

I can’t say that I am in terrific pain at all…any time. I have been very fortunate regarding that. Not, not the pain that the wife gets

(P14).

This patient felt lucky despite experiencing pain at a moderate level from various areas of the body.

The belief that pain was to be expected with cancer meant that there was some resignation, and an expectation that pain, to some degree, was to be tolerated:

I tell myself well yes it hurts you. But still, it seems to me that it can be tolerated.

(FCG15)

For some, enduring pain from comorbidities or a long cancer trajectory meant that pain had become the norm; resulting in increased tolerance and a familiarity at dealing with pain. As one patient remarked:

I can live with a 4 [ESAS rating] yes. I have lived with a 4 predominantly a lot of my life. Yes from back pains. I have had many back pains for years and problems and a 4 has been pretty steady for me.

(P8)

Several caregivers described their family member as having a high pain threshold because of the pain that they had endured over the illness trajectory. Still, participants also spoke of the pain “wearing them down” due, in part, to increasing pain, cancer and noncancer-related symptoms, and functional changes attributed to aging. Age was also mentioned in terms of advanced age decreasing patients’ mental and physical resources to cope with the pain. Cognitive strategies previously successful in dealing with pain, such as distraction, ignoring the pain or an attitude of “grin and bear it” (P15), became limited in effectiveness as a result,

My mind had the ability to block off pain. In other words, I could reduce the pain ... to where it was manageable. But as I got... older and older …I started to realize that my mind could no longer block the pain…It has lost its ability to shut out the pain.

(P15)

Important in dealing with more intense pain was a sense of control. Despite confidence in being able to tolerate or manage less intense levels of pain, the majority of participants, at some point in time, had experienced a sense of helplessness when dealing with episodes of uncontrollable pain. A daughter caregiver, put into words her feelings at watching her mother in pain:

Although she takes her drugs we don’t know to what point she feels relieved… That affects us in the sense that we feel really impotent to help her even with the drugs, to see her suffering.

(FCG3)

Another caregiver described her reaction to her husband’s pain:

I’m so much accustomed to hearing ouch, ouch, ouch and to see him hold himself that… I find it’s a shame but I can’t do much.

(FCG20)

Still, the changing nature of the pain meant that even when pain control was achieved, there was concern about how the pain might change in the future. As a consequence, a common response was to take it “day-by-day”.

Emotional reactions:

Living with pain became tiresome and distressing for participants, especially over long periods and at intense levels. Caregivers noticed changes in patients’ moods as a result of the pain. Anger and irritability were frequently expressed by patients toward the pain, themselves and others (health care professionals, God, family members). One patient commented:

I can say that when you feel pain, over a long period, for a long time, it affects your mood, you become irritable, you say why me, why do I have so much now.

(P20)

These emotional reactions were sometimes in relation to the consequences of pain, in terms of reductions in functioning.

Caregivers described the distress they experienced witnessing what they viewed as suffering. Recalling her reactions to seeing her mother in pain, one caregiver stated:

It [the pain] kind of brings me down yes definitely I have noticed that it’s hard because there is no improvement it is constant … it is personal yah it’s your mother and you know you feel bad and everything and I don’t want it to get me depressed either. Get me down all the time.

(FCG12)

The sense of helplessness described by caregivers in trying to manage uncontrollable pain was upsetting, as the following response conveys:

I’m a man who likes to see things settled, to find a solution ... if I don’t have a solution, I’m despondent.

(FCG20)

For some caregivers, there was also frustration and anger directed toward the patient and health care professionals for not managing the pain. Several caregivers mentioned that the patient was reluctant to take analgesics prophylactically or would forget to take them, which resulted in episodes of severe pain.

Living with cancer pain

The theme ‘living with the pain’ incorporated individual and social-relational changes that resulted from living with cancer pain. Three subthemes represented the effects of the pain on the lives of patients (‘functioning with cancer pain’), caregivers (‘caring for a family member with cancer pain’) and the relationship between the two (‘cancer pain in the relationship’). A feature of this theme was that the pain experience was perceived within the context of patients’ and care-givers’ current functioning and ongoing relationship.

Functioning with cancer pain:

Most patients spoke of a loss of functioning and dependence on others when they talked about pain. However, these losses were also discussed in relation to cancer, its treatment (chemotherapy) and cancer-related symptoms such as weakness and fatigue. An added issue was the presence of comorbidities that contributed to a loss of functioning. Several patients had sensory deficits and a reduction in functioning, which participants viewed as a result of aging and disease. The presence of pain added to the losses that many were already experiencing. One patient who had lived most of his life with pain described how life had changed since he had cancer:

It changed my whole life.. since then ... All of a sudden. I was a guy with pain … but I could get around. Now, I am in pain plus I can’t get around.

(P15)

In general, patients tried to maintain some semblance of normalcy by tolerating some degree of pain. However, at intense levels, pain severely disrupted functioning. This meant usual daily activities were difficult to accomplish. For patients, disruption to their functioning was significant and was often used to illustrate the strength of their pain.

Caring for a family member with cancer pain:

Caregivers were critical in meeting the care needs of patients, especially in relationships in which they resided together. For some caregivers, this was a supportive role, assisting the patient with self-management (ie, coordinating services to the home, acquiring prescribed medicines and attending medical appointments), while, for others, it was more extensive, consisting of pain assessment and the selection and implementation of pain treatment strategies, as well as the management of side effects. Aside from the cancer and its consequences, caregivers were often dealing with ongoing issues and declines in patients’ functioning due to comorbidities (ie, diabetes, arthritis, heart disease) and symptoms such as urinary frequency, dizziness, falls, memory loss, shortness of breath and fatigue. Although cancer added to patients’ functional decline and increased caregivers’ roles and responsibilities, it was viewed as a gradual process whereby the caregiver gradually took on more responsibility, as one caregiver stated:

This experience I think, it didn’t throw me for a loop because he really has not been all that great in the last 10 to 15 years so I think you work your way into it.

(FCG11)

Caregivers living with patients spoke of habitual vigilance for signs of pain, and regular monitoring and/or administration of analgesic regimens. This meant that they needed to be around the patient, which prevented them from engaging in their normal activities. Because episodes of severe pain often occurred at night, waking the patient, caregivers routinely had their sleep disrupted.

Cancer pain in the relationship:

Pain took precedence in the lives of many participants and became a constant reminder of the illness. This diverted attention away from other aspects of life and relationships with others. Describing how pain had become a defining feature and the primary focus of interaction with others, one patient commented:

For my children, their first question is “How do you feel today?” …and you know it’s… It has changed the whole relationship in the sense that they are concerned about my pain.

(P15)

Other patients spoke of “being strong” for certain family members who did not want to see them in pain.

When patients described their relationships, they spoke of the effect on those around them. Talking about his wife one patient responded:

She’s [wife]…persevered but I don’t know for how long. How much longer she can! And I am worried about that. I am not worried about myself.

(P15)

Caregivers were themselves worried about the effects on their own health and also how they would cope if the patient’s condition deteriorated, especially in partner relationships in which the caregiver was older.

There were inevitable changes in roles, responsibilities and functioning for participants. This was less apparent in relationships in which the caregiver was not living with the patient and in nonpart-ner relationships. In these circumstances, there was a strong sense from patients of wanting to remain independent and reluctance to seek help from caregivers. In couples, changes in roles and responsibilities were more apparent because there was an assumed reliance on the partner regardless of the quality of the relationship. In relationships characterized as mutual and close, caregivers talked of no major changes in the relationship; pain and sickness became an accepted part of the relationship. Indeed, some caregivers talked of increasing closeness having shared this experience. Managing the patient’s pain and care, although challenging, brought with it some satisfaction in being able to assist in times of need. However, at the same time, greater dependence meant more changes as the patient relinquished roles, which sometimes brought friction into the relationship as patients tried to maintain control. In two partner relationships that were not strong, the losses associated with having to provide care lead to resentment toward the patient and a loss of freedom, as one caregiver stated:

Well our whole life is just around him now you know it’s just pretty much every day it’s all about him. I guess he’s a victim.

(FCG2)

As the relationship had broken down, the sense of responsibility for the other person had diminished. Out of necessity, the partner had become the caregiver, and there was anger and bitterness.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, cancer pain was explored from the perspectives of older patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers living at home. Three main themes were identified, which encompassed the multidimensional and dynamic experience of cancer pain within the context of palliative care, the caregiving relationship and aging. Consistent with others, we found that cancer pain affects patients’ physical, social, existential and psychological well-being (17,26). Caregivers’ reactions to patients’ pain, its meaning and the resultant challenges highlight the shared nature of the experience, a finding that has been identified by others (25,48). The presentation of the findings from both patients and caregivers within the same thematic framework gives emphasis to the dynamic between these experiences in relation to cancer pain.

Participants’ narratives highlighted some of the unique challenges faced by these older patients and their caregivers. Participants identified various pains and other symptoms associated with cancer, comorbidities and age-related declines in functioning. This finding is not unexpected given the higher incidence of comorbidities in this population (14) and greater likelihood of noncancer pain (15). Although we did not seek to examine the effects of comorbidities on pain intensity, this finding is noteworthy because the incidence of comorbid conditions has been shown to increase pain (49). Our study did, however, reveal that noncancer pain made identifying the origin of the pain more difficult for patients and caregivers, given the various sources, locations and types. The inability to distinguish between several types of pain is significant because different interventions may be required. Mehta et al (40) found that caregivers unable to discriminate between different types of pain selected pain strategies that were not appropriate. Health care professionals can support patients and caregivers by helping them to assess the various cancer and noncancer pains (ie, location, frequency and type of pain) and to identify the most appropriate pain management interventions.

Beyond the identification of pain were daily challenges as a result of pain, exemplified in the categories ‘reacting to cancer pain’ and ‘living with cancer pain’. Patients’ and, to a lesser extent, caregivers’ responses revealed acceptance and tolerance of pain at low to moderate levels of intensity. Certainly, there was an attitude of ‘getting on with life’ regardless of the pain. This attitude may reflect knowledge deficits, attitudes toward medications and expectations of pain with aging, cancer and death (30–33). At the same time, the desire to continue to function in spite of pain could signify greater resilience and an ability to adapt based on experience dealing with age-related changes and other health issues. Gagliese et al (50) found that older patients with cancer pain were more likely than their younger counterparts to modify activities and goals to accommodate pain, rather than wait to be pain free. Because there is an emphasis on maximizing functioning, they suggest that acceptance of pain be considered a management goal (50). Health care professionals, therefore, need to be mindful that some older patients and caregivers may bring their experience, knowledge and preferences from dealing with other health issues and non-cancer pain to bear on the current situation of cancer pain. Thus, the effectiveness of coping strategies should be assessed in terms of the goals of treatment, while ensuring that any misconceptions, concerns and knowledge deficits are addressed.

Although there was some tolerance for mild and moderate pain, there was little acceptance of pain at more intense levels of pain. In this situation, pain became synonymous with suffering. For patients, pain management approaches that had been effective no longer alleviated the pain. Severe pain also added to health- and age-related functional limitations, and in combination with cancer-related symptoms, especially fatigue and weakness, this was compounded. Although pain and fatigue frequently occur in patients with cancer, in older patients these symptoms are predictive of impaired physical functioning and the presence of others symptoms (ie, depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance) (51). Consideration, therefore, has to be given to the likely effects of related symptoms and comorbidities on cancer pain in older patients. Future research efforts should be directed toward understanding the impact of aging and comorbidities on the cancer symptom experience (51).

Greater patient functional limitations meant a corresponding increase in caregiving responsibilities, workload and restrictions. Most caregivers appreciated the opportunity to care for their family member, although, similar to the results of other studies (23–25), pain management was especially challenging at intense levels. In view of the difficulties that caregiving can impose and the potential effects of uncontrollable pain on the health and well-being on caregivers and patients, care assessment and planning should be directed toward the patient and caregiver. Here, the palliative care philosophy of the patient and family as the unit of care takes precedence. This is especially important for older patients, whose partner caregivers are likely to be older and have their own health issues. Furthermore, the assumption that family members will wholeheartedly take on the role of caregiver should be challenged because not all caregivers are willing or able to take on this role. Health care professionals could facilitate an honest and open dialogue with family about the caregiver role and the extent of their involvement over the course of the disease trajectory. Future research should aim to improve understanding of the issues of caregiving choice and obligation given the potential implications for family members and patient care (52).

Exploring the experience of pain, we found, similar to others, that cancer pain had meaning (34,35). The existential significance of pain as advancing illness was an ever-present reminder of the cancer. Fatalistic beliefs about the increasing presence of pain and inevitability of death were expressed, albeit mainly by patients. Of particular significance for these older patients was that intense pain came to signify a loss of independence and dependence on others. Pain had existential significance, became a defining feature of the individual and compounded psychological suffering (ie, dependency and losses, the sense of being a burden to others). These descriptions of pain in terms of losses and dependence, relinquished social roles and impending death resonate with Dame Cicely Saunders’ concept of ‘total pain’ (18). Because old age brings with it many adjustments in roles and functioning, it is probable that older patients are dealing with other issues that could augment pain and psychological suffering (ie, dependency, isolation). Failure by health care professionals to recognize and address both pain and associated psychological suffering will lead to inadequate pain control and caregiver suffering.

It is important to acknowledge some key points and limitations to the study. First, our focus was on patients and caregivers, but home care does not occur in a vacuum. Barriers to pain management are identified at the system and health care professional level (29,32). By not attending to these issues, it is unlikely that patients’ pain will be appropriately managed. Second, we sought to sample various types of relationships, but our sample was limited to mainly longstanding partner relationships with female caregivers. Future research would benefit from examining the perceptions of individuals in other types of relationships and also multiple caregivers caring for one family member. Third, we used several strategies to ensure rigour in our study including analysis of the transcripts by researchers who knew the data intimately and were involved in the interviews, collaboration on the main themes and subthemes by the research team with various backgrounds, and the use of an audit trail of decisions. Ideally, member checking by contacting the participants to verify the main themes and subthemes would have increased credibility. However, due to the circumstances, this was not possible because most patients had already died and family members were bereaved.

CONCLUSION

Although aging can bring with it distinct issues that can affect how cancer pain is experienced and managed, pain should not be viewed as an inevitable part of aging, dying or cancer. Age can bring with it life experiences that can help patients and caregivers cope with the difficulties they encounter. Furthermore, heterogeneity in the older population points to the need for an individualized approach to pain management based on patients’ subjective experience of cancer pain and situated within the context of the patient’s current health and functioning including the physical (ie, physiological age-related changes, symptoms and comorbidities), social (ie, relationships, culture and care setting), psychological (ie, distress, coping and cognition) and spiritual (ie, meanings and loss). The challenges that aging, advanced disease and cancer pain present highlight the need for skilled and knowledgeable health care professionals with understanding of cancer pain assessment and management in older individuals. Furthermore, the findings make it difficult to separate the caregiver from the patient in the experience of advanced cancer pain in the home setting. Their interdependence points to the need to include the caregiver and focus care on improving patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life.

SUMMARY

Pain in older individuals with advanced cancer is common and its management is complex. Compared with health care settings, in the home, there is greater reliance on self and family caregivers. An understanding of cancer pain from the perspectives of older patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers is essential for addressing the needs of these individuals and for identifying factors that contribute to inadequate management. In the present qualitative study, these perspectives and experiences are described. The findings emphasize the need to assess cancer pain within the individual’s current circumstances in the context of life-limiting illness, caregiving and aging.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded through a New Emerging Team Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yancik R, Ries LA. Cancer in older persons: An international issue in an aging world. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:128–36. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delgado-Guay MO, Bruera E. Management of pain in the older person with cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: A systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437–49. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . National Cancer Control Programmes: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Cancer Pain Relief: With a Guide to Opioid Availability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:592–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann MT, Farnon CU, Javed A, Posner JD. Pain in the elderly hospice patient. Am J Hospice Palliat Care. 1998;15:259–65. doi: 10.1177/104990919801500506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Payne R. Anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63:2266–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2266::aid-cncr2820631135>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: Definition, prevalence and characteristics. Pain. 1990;41:273–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90004-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twycross R, Harcourt J, Bergl S. A survey of pain in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;12:273–82. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balducci L. Management of cancer pain in geriatric patients. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:175–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yancik R, Ganz PA, Varricchio CG, Conley B. Perspectives on comorbidity and cancer in older patients: Approaches to expand the knowledge base. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1147–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:205–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.50.6s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melzack R, Wall PD. The Challenge of Pain. 2nd edn. London: Penguin Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SR, Mount BM. Pain with life-threatening illness: Its perception and control are inextricably linked with quality of life. Pain Res Manag. 2000;5:271–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders C. The Management of Terminal Malignant Disease. 1st edn. London: Edward Arnold; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duggleby W. Elderly hospice cancer patients’ descriptions of their pain experiences. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2000;17:111–7. doi: 10.1177/104990910001700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsend J, Frank A, Fermont D, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients’ preference for place of death: A prospective study. BMJ. 1990;301:415–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrell BR, Cohen MZ, Rhiner M, Rozek A. Pain as a metaphor for illness. Part II: Family caregivers’ management of pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:1315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yates P, Aranda S, Edwards H, Nash R, Skerman H, McCarthy A. Family caregivers’ experiences and involvement with cancer pain management. J Palliat Care. 2004;20:287–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones S, Hadjistavropoulos H, Janzen J, Hadjistavropoulos T. The relation of pain and caregiver burden in informal adult caregivers. Pain Med. 2011;12:51–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallerand AH, Saunders MM, Anthony M. Perceptions of control over pain by patients with cancer and their caregivers. Pain Manag Nurs. 2007;8:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrell BR, Taylor EJ, Grant M, Fowler M, Corbisiero RM. Pain management at home: Struggle, comfort, and mission. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63:2321–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caltagirone C, Spoletini I, Gianni W, Spalletta G. Inadequate pain relief and consequences in oncological elderly patients. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrell BR, Rhiner M, Cohen MZ, Grant M. Pain as a metaphor for illness. Part I: Impact of cancer pain on family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:1303–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gee RE, Fins JJ. Barriers to pain and symptom management, opioids, health policy, and drug benefits. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:101–3. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–24. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward S, Gatwood J. Concerns about reporting pain and using analgesics: A comparison of persons with and without cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: A review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:358–6. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig KD, Hadjistavropoulos T. Psychological perspectives on pain: Controversies. In: Hadjistavropoulos T, Craig KD, editors. Pain: Psychological Perspectives. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 303–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrell BR, Dean G. The meaning of cancer pain. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1995;11:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aranda S, Yates P, Edwards H, Nash R, Skerman H, McCarthy A. Barriers to effective cancer pain management: A survey of Australian family caregivers. Eur J Cancer Care. 2004;13:336–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2004.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dar R, Beach CM, Barden PL, Cleeland CS. Cancer pain in the marital system: A study of patients and their spouses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(92)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duggleby W. Enduring suffering: A grounded theory analysis of the pain experience of elderly hospice patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:825–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrell BR, Ferrell BA, Rhiner M, Grant M. Family factors influencing cancer pain management. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:64–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta A, Cohen SR, Carnevale FA, Ezer H, Ducharme F. Strategizing a game plan: Family caregivers of palliative patients engaged in the process of pain management. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:461–9. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181de72cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta A, Cohen SR, Ezer H, Carnevale FA, Ducharme F. Striving to respond to palliative care patients’ pain at home: A puzzle for family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:E37–45. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E37-E45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor EJ, Ferrell BR, Grant M, Cheyney L. Managing cancer pain at home: The decisions and ethical conflicts of patients, family caregivers, and homecare nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1993;20:919–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta A, Ezer H. My love is hurting: The meaning spouses attribute to their loved ones’ pain during palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. London: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tesch R. Qualitative Research: Analysis Types and Software Tools. London: RoutledgeFalmer Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): A new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Borneman T, Juarez G, ter Veer A. Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:185–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Given CW, Given B, Azzouz F, Kozachik S, Stommel M. Predictors of pain and fatigue in the year following diagnosis among elderly cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:456–66. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gagliese L, Jovellanos M, Zimmermann C, Shobbrook C, Warr D, Rodin G. Age-related patterns in adaptation to cancer pain: A mixed-method study. Pain Med. 2009;10:1050–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiner A, Lacasse C. Symptom correlates in the gero-oncology population. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2006;22:20–3. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Funk L, Kobayashi K. “Choice” in filial care work: Moving beyond a dichotomy. Can Rev Sociol. 2009;46:235–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-618x.2009.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]