Abstract

Diffuse intrapulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia is a rare, potential precursor lesion to typical pulmonary carcinoid tumours. Fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature. Their pathogenesis, clinical significance and management is controversial. A patient who presented with diffuse intrapulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia associated with a primary typical carcinoid tumour of the lung is reported.

Keywords: Carcinoid tumour, Lung cancer, Neuroendocrine tumours

Abstract

L’hyperplasie neuroendocrine pulmonaire diffuse est une lésion rare au potentiel précurseur de tumeurs carcinoïdes pulmonaires classiques. Moins de 50 cas ont été signalés dans les publications. Leur pathogenèse, leur signification clinique et leur prise en charge sont controversées. Les auteurs présentent le cas d’un patient qui a consulté en raison d’une hyperplasie neuroendocrine pulmonaire diffuse associée à une tumeur carcinoïde primaire classique du poumon.

Learning Objectives

Ability to recognize the presentation and clinical associations of diffuse intrapulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH).

Understand the limited available evidence for optimal management of DIPNECH.

CanMEDS competency: Medical Expert

Pretest

What is DIPNECH?

What is the optimal management of DIPNECH?

CASE PRESENTATION

A 68-year-old woman presented with progressive exertional dyspnea, cough and limited exercise tolerance. Her medical history was notable for obstructive lung disease, hypertension and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-opherectomy for ovarian carcinoma at 34 years of age without adjuvant therapy. She had no history of smoking, or of occupational or other infectious exposure.

Examination at rest revealed an obese Caucasian female without cyanosis or clubbing. There was no palpable lymphadeopathy and no hepatosplenomegaly. Auscultation revealed clear breath sounds bilaterally with regular heart sounds. Clinically, she exhibited wheezing but no other signs of carcinoid syndrome.

Pulmonary function assessment revealed an obstructive pattern with a forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 1.80 L (69% predicted). Stage I exercise testing revealed maximum oxygen consumption of 13.7 mL/kg/min (60% predicted). Additional work-up with thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a round 10 mm × 14 mm dominant nodule in the right middle lobe and at least 20 tiny bilateral indeterminate pulmonary nodules (Figures 1 and 2). Subsequent needle biopsy of the right middle lobe confirmed typical carcinoid tumour. Staging with positron emission CT scan revealed weak metabolic activity in the nodule with a maximum standardized uptake value of 1.80 and no metastatic disease.

Figure 1).

Bilateral lower lobe nodules with air trapping

Figure 2).

Right middle lobe typical carcinoid tumour

The patient underwent a right middle lobectomy and wedge resection for diagnosis of the tiny nodules deep within the parenchyma of the lower and upper lobes. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated.

Histopathological examination revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm 1.2 cm in size in the right middle lobe classified as pT1a, pN0 typical carcinoid (TNM staging). Ovoid to spindle cells arranged in nests and trabeculae had very low cellular proliferation (<1 mitosis/10 high-power fields) and no necrosis (Figure 3). There were multiple peribronchiolar and subpleural foci of neuroendocrine cell proliferation exhibiting linear subepithelial proliferation limited by the basement membrane (DIPNECH), as well as tumourlets (0.1 cm to 0.4 cm in greatest dimension) penetrating the basement membrane (Figure 4). The right lower wedge resections also revealed DIPNECH separate from carcinoid tumourlet foci (0.2 cm to 0.4 cm).

Figure 3).

A Typical carcinoid tumour. B Histopathological features of typical carcinoid tumour at high power (original magnification ×200); uniform round to polygonal cells with small nuclei and abundant cytoplasm, no evidence of necrosis or mitosis. C Special stains for typical carcinoid include synaptophysin. D Ki-67 staining showing <2% nuclear labelling index

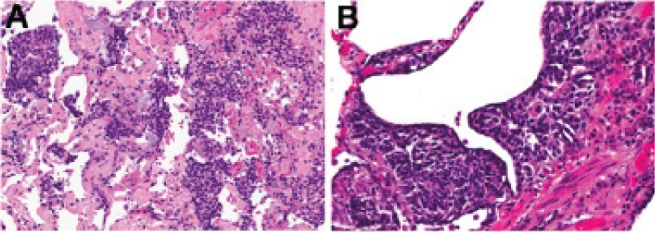

Figure 4).

A Representative section showing diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. B High-power photomicrograph showing subepithelial cell proliferation

Her case was reviewed in thoracic oncology multidisciplinary rounds. The consensus was no adjuvant therapy but continued surveillance with clinical assessment and thoracic CT every four months.

DISCUSSION

The existence of precursor lesions for pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours remain controversial (1). DIPNECH is a proposed precursor lesion to a typical carcinoid tumour (1,2). It is a rare clinical entity of diffuse airway neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia, with <50 reported cases. Symptomatic patients exhibit a syndrome with clinical and pathological components: small airway obstruction or interstitial lung disease (wheeze, dyspnea and cough) with histological findings of neuroendocrine cell proliferation and bronchiolar fibrosis (3,4).

The WHO incorporated DIPNECH into its classification system for neuroendocrine tumours as a precursor to typical carcinoid tumours (5). The 2004 WHO classification defines DIPNECH as a proliferation of scattered single pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, nodules or linear proliferations of these cells confined to bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. If proliferation extends beyond the basement membrane, it is termed a ‘carcinoid tumourlet’ (1), defined as carcinoid tumours ≤5 mm in size. Mitotic activity is very low and necrosis is absent (6). Size is the only feature distinguishing a carcinoid tumourlet from typical carcinoid tumours, which are >5 mm in diameter.

DIPNECH is believed by some to be an under-recognized entity, now becoming apparent due to advances in CT scan technology and increased general awareness (7). Reported clinical presentations are variable. Asymptomatic patients are identified incidentally after imaging studies including mistaking DIPNECH for metastatic disease or for work-up of trauma (7). In symptomatic individuals, dyspnea or cough usually develop slowly, often initially misdiagnosed as asthma (1). Pulmonary function tests typically reveal an obstructive pattern (1,7,8).

With regard to demographics, DIPNECH is reported four times more frequently in women than in men, usually nonsmokers in the fifth or sixth decade of life (1,7). The most frequent radiographic features include mosaic air trapping and multiple small nodules (1). Bronchial wall thickening or larger carcinoid nodules may also be apparent (Figures 1 and 2).

In case series, DIPNECH is found in association with typical carcinoid tumours, especially peripherally located spindle cell typical carcinoids (7,9–11). It is not reported in association with high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours such as small-cell lung carcinoma or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (1). One series reported DIPNECH with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (7), and another with adenocarcinoma of mixed subtype and partial neuroendocrine differentiation (12). Very rarely, it is reported with ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone production (13) and elevated serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels in the absence of pulmonary or primary gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma (14). DIPNECH has also been found on surgical lung biopsy of patients with respiratory failure of unclear etiology requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation (15).

The gold standard for definitive diagnosis of DIPNECH is surgical lung biopsy (15). A diagnosis cannot be reliably achieved with a transbronchial or transthoracic biopsy. Surgical biopsy with sizable tissue is desired because, by definition, DIPNECH is a multifocal process (neuroendocrine hyperplasia in the peribronchial areas as well as often in the distal parenchyma confined to the epithelium).

Although fibrosis may be evident between the smooth muscle layer and epithelium of the small airways (1), some hypothesize fibrosis is due to neuroendocrine proliferation with peptides (bombesin) produced by neuroendocrine cells and not vice versa (9,11). To date, no characteristic molecular alterations associated with DIPNECH have been identified. In addition to fibrosis, DIPNECH has been recognized as a reactive process in the setting of chronic inflammatory disease processes including bronchietasis and obliterative bronchiolitis (1,6).

The natural history of DIPNECH appears to be favourable; most patients experience stable or very slowly progressive disease (3). A small number of cases report progressive DIPNECH leading to severe diffuse small airway obstruction and respiratory failure from endobronchial lesions and fibrosis requiring intubation (9,10,15).

Owing to its rarity, the optimal management of DIPNECH remains poorly defined. Long-term surveillance is generally accepted to monitor for progression to typical carcinoid tumour (8). However, optimal time intervals for surveillance and the preferred imaging modality is as yet unclear. With respect to the symptoms of obstructive airway disease, inhaled bronchodilators or steroids may prove to be beneficial. The role of surgery in the management of DIPNECH is controversial and, in existing case series, has been limited to patients who develop an associated carcinoid tumour (3,16).

Post-test

-

What is DIPNECH?

DIPNECH is a rare disease of diffuse airway neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. The WHO defines DIPNECH as a proliferation of scattered single pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, nodules or linear proliferations of these cells confined to bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. DIPNECH may be associated with a clinical-pathological syndrome of airway obstruction or interstitial lung disease (wheeze, dyspnea, cough) due to the histological findings of neuroendocrine cell proliferation and bronchiolar fibrosis.

-

What is the optimal management of DIPNECH?

The optimal management of DIPNECH is poorly defined owing to its rarity. Long-term surveillance is advocated to monitor for progression to typical carcinoid tumour. The role of pulmonary resection is currently limited to patients with an associated carcinoid tumour. Inhaled bronchodilators or steroids may aid in symptom management of obstructive airway disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beasley MB. Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumours and proliferations: A review and update. Diagnost Histopathol. 2008;14:465–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink K, Harris C. Pathology and Genetics Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkenstern-Ge RF, Kimmich M, Friedel G, Tannapfel A, Neumann V, Kohlhaeufl M. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: 7-year follow-up of a rare clinicopathologic syndrome. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1495–8. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis WD. Lung tumours with neuroendocrine differentiation. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(Suppl 1):251–66. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(09)70040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermlink HK, Harris CC, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitwell F. Tumourlets of the lung. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1955;70:529–41. doi: 10.1002/path.1700700231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies SJ, Gosney JR, Hansell DM, et al. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: An under-recognised spectrum of disease. Thorax. 2007;62:248–52. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.063065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge Y, Eltorky MA, Ernst RD, Castro CY. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RR, Muller NL. Neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and obliterative bronchiolitis in patients with peripheral carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:653–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199506000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aubry MC, Thomas CF, Jr, Jett JR, Swensen SJ, Myers JL. Significance of multiple carcinoid tumors and tumorlets in surgical lung specimens: Analysis of 28 patients. Chest. 2007;131:1635–43. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguayo SM, Miller YE, Waldron JA, Jr, et al. Brief report: Idiopathic diffuse hyperplasia of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and airways disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1285–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210293271806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warth A, Herpel E, Schmahl A, Storz K, Schnabel PA. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia in association with an adenocarcinoma: A case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron CM, Roberts F, Connell J, Sproule MW. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: An unusual cause of cyclical ectopic adrenocorticotrophic syndrome. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e14–e17. doi: 10.1259/bjr/91375895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitiyanant P, Pitiguagool V, Suchato C, Varatorn R. Diffuse pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia with tumorlets and elevated serum CEA. Bangkok Med J. 2011:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nassar AA, Jaroszewki DE, Helmers RA, Colby TV, Patel BM, Mookadam F. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia A systematic overview. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:8–16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1685PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swigris J, Ghamande S, Rice T, Farver C. Diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia: An interstitial lung disease with airway obstruction. J Bronchol. 2005;12:62–5. [Google Scholar]