Abstract

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are neural crest cell tumors of the adrenal medulla and parasympathetic/sympathetic ganglia, respectively, that are often associated with catecholamine production. Genetic research over the years has led to our current understanding of the association 13 susceptibility genes with the development of these tumors. Most of the susceptibility genes are now associated with specific clinical presentations, biochemical makeup, tumor location, and associated neoplasms. Recent scientific advances have highlighted the role of somatic mutations in the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma as well as the usefulness of immunohistochemistry in triaging genetic testing. We can now approach genetic testing in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma patients in a very organized scientific way allowing for the reduction of both the financial and emotional burden on the patient. The discovery of genetic predispositions to the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma not only facilitates better understanding of these tumors but will also lead to improved diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

Key Terms: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, VHL, MEN2, NF1, SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2, TMEM127, MAX, HIF2A, HRAS

Introduction

Our understanding of the genetic basis of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas (tumors of neural crest origin typically associated with catecholamine secretion) is rapidly increasing. We have moved from the “10% tumor” to the “10 gene tumor” to our current understanding of 13 susceptibility genes: the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene; the RET gene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2); the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) gene associated with von Recklinghausen’s disease; mutations of the A, B, C, and D subunits of the mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDH); the SDHAF2 gene; TMEM127 gene mutations; MAX gene mutations; PHD2; and the recently described: H-RAS (Crona, Delgado Verdugo, Maharjan et al., 2013) and gain-of-function HIF2α mutations (Zhuang, Yang, Lorenzo et al., 2012). Approximately 35% of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are associated with an inherited mutation (Amar, Bertherat, Baudin et al., 2005, Gimenez-Roqueplo, Burnichon, Amar et al., 2008) and, as recently reported, approximately 14% of sporadic tumors demonstrate somatic mutations (Burnichon, Vescovo, Amar et al., 2011). As research has advanced, we have become more and more aware of the role that genetics play in the pathogenesis of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Greater understanding of the genetic background will allow for further advancements in diagnostic and treatment options for pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma patients as well as continue the move towards individualized patient care.

While knowledge of an individual patients’ mutation is extremely helpful in personalizing care, clustering of the different genetic mutations may help guide advances in diagnostic approaches and discoveries of new therapeutic opportuinties. Currently, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma predisposing genetic mutations are most commonly clustered based on transcriptomes: Cluster 1 = hypoxic transcriptional signature (SDH genes = 1A and VHL gene = 1B), HIF2α; Cluster 2 = kinase receptor signaling and protein translation (RET, NF1, TMEM127, MAX) (Eisenhofer, Huynh, Pacak et al., 2004, Dahia, Ross, Wright et al., 2005, Lopez-Jimenez, Gomez-Lopez, Leandro-Garcia et al., 2010). Several large clinical pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma studies have helped elucidate the clinical presentation of these tumors associated with different genetic mutations. Here we will discuss the 13 genes that are currently known to be associated with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma and the clinical presentation associated with these specific genetic defects. We will also provide a recommendation on how to approach genetic testing for pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma patients based on clinical presentations, gene-specific biochemical phenotypes, and specific tumor locations. Approaching genetic testing using an individual patients’ clinical presentation is considered cost-effective, timely and valuable for early and effective treatment of patients with hereditary pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma.

VHL

VHL encodes the von Hippel-Lindau protein, which functions as a regulator of hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIFα) – marking HIFα for degradation under normoxic conditions - and thereby controls blood vessel formation, energy metabolism, and apoptosis (Maxwell, Wiesener, Chang et al., 1999, Carmeliet, Dor, Herbert et al., 1998, Min, Yang, Ivan et al., 2002). Loss of function mutations in the VHL gene results in stabilization of HIFα leading to downstream transcription of cellular proliferation genes and to von Hippel-Lindau disease. von Hippel Lindau is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by development of various benign and malignant tumors including pheochromocytomas and, rarely, paragangliomas.

von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease was first described over 100 years ago and since that time the clinical features of this disease have been extensively studied. VHL is characterized by predisposition to a variety of tumors including hemangioblastomas, retinal angiomas, clear cell renal carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic tumors, epididymal cystadenomas, and cysts of the kidney and pancreas (Maher, Yates, Harries et al., 1990, Choyke, Glenn, Walther et al., 1995). VHL is clinically broken down into VHL type 1, which is not associated with pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas, and VHL type 2, which is associated with pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas (Chen, Kishida, Yao et al., 1995). VHL type 2 is further broken down into type 2A, which does not have a predisposition for clear cell renal carcinoma; type 2B, which is essentially type 1 (retinal angiomas, central nervous system hemangioblastomas, clear cell renal carcinoma, cysts of kidney and/or pancreas) with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma; and type 2C, which is pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma without other VHL associated lesions (Maher et al., 1990).

The adrenal medulla is the most common location of VHL-related pheochromocytoma though sympathetic and parasympathetic tumors have been described. VHL-related pheochromocytomas are often bilateral and can be multiple but metastatic disease rarely occurs thus, these tumors have an overall good prognosis. Patients typically present around 30 years of age, though presentation of other VHL-related lesions often occurs much earlier. The biochemical make up of VHL-related pheochromocytomas is primarily solitary secretion of norepinephrine, related to a low, or no, expression of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) (Maher et al., 1990, Delman, Shapiro, Jonasch et al., 2006, Maher, Neumann and Richard, 2011, Lonser, Glenn, Walther et al., 2003, Eisenhofer, Lenders, Timmers et al., 2011).

RET Proto-Oncogene

The RET proto-oncogene encodes a tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptor that functions in the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Activating mutations of this proto-oncogene lead to the autosomal dominant syndrome known as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2)(Santoro, Carlomagno, Romano et al., 1995, Frank-Raue, Kratt, Hoppner et al., 1996). MEN2 syndrome has been well characterized and can be divided into three subgroups: MEN2A, MEN2B, and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (not associated with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma). MEN2A mutations are associated with a disulfide bond disruption causing active homodimers to increase tyrosine kinase activity. MEN2B mutations are known to alter the substrate specificity of RET(Santoro et al., 1995).

Clinically, MEN2A is associated with development of medullary thyroid carcinoma in all patients, a 50% risk for pheochromocytoma, and a 10–30% risk for development of hyperparathyroidism (Howe, Norton and Wells, 1993). MEN2B is associated with a nearly 100% risk of developing medullary thyroid carcinoma (earlier onset as compared to MEN2A), a 50% risk for development of pheochromocytoma, mucosal ganglioneuromas, and a marphanoid habitus (Brauckhoff, Machens, Hess et al., 2008, Wohllk, Schweizer, Erlic et al., 2010).

MEN2 associated pheochromocytomas are typically adrenal, often bilateral, and very infrequently associated with metastatic disease, translating to excellent prognosis in the majority of patients. MEN2B associated pheochromocytoma presenting in childhood, however, is associated with an increased risk of metastatic disease as compared to MEN2A and sporadic tumors (Pacak, Eisenhofer and Ilias, 2009). MEN2 related pheochromocytomas tend to be diagnosed between 30 and 40 years of age (Amar et al., 2005, Pacak et al., 2009, Mannelli, Castellano, Schiavi et al., 2009, Bryant, Farmer, Kessler et al., 2003, Lenders, Eisenhofer, Mannelli et al., 2005) and are typically associated with hypersecretion of epinephrine (Eisenhofer et al., 2011). In contrast to medullary thyroid carcinoma, which is the part of the MEN syndrome, there is no known specific genotype-phenotype correlation related to pheochromocytoma.

NF1

The neurofibromatosis type 1 tumor suppressor gene encodes a protein that inhibits the RAS signaling cascade and the mTOR kinase pathway, and therefore controls cellular growth and differentiation (Johannessen, Reczek, James et al., 2005). Inactivating mutations of NF1 lead to the autosomal dominant disorder von Recklinghausen’s disease or neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Genetic testing for NF1 mutations is not commonly performed because of the large size of the gene, resulting in a high cost for testing, and because diagnosis can be made clinically. Clinical diagnosis is made when a patient has two or more of the following: six or more caf -au-lait spots; two or more cutaneous neurofibromas or a plexiform neurofibroma; inguinal or axillary freckles; one or more optic nerve gliomas; dysplasia of sphenoid bone or pseudoarthrosis; two or more benign iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules); first degree relative with NF1 (1988). Patients with NF1 are at risk for the development of various tumors including neurofibromas, medullary thyroid carcinoma, carcinoid tumors, parathyroid tumors, peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and pheochromocytomas (1988, Zoller, Rembeck, Oden et al., 1997).

Pheochromocytomas are rare in patients with NF1 with the literature reporting only approximately 1% of patients develop pheochromocytomas (Riccardi, 1991). When pheochromocytoma does occur in patients with NF1 it tends to be an adrenal tumor that preferentially secretes epinephrine similarly to those found in MEN syndrome. These tumors typically present in the patients 40s (in comparison to the dermal neurofibromas and other findings that can arise in childhood). Metastatic disease, although rare (similar to MEN syndrome), has been documented in patients with NF1 and pheochromocytoma (Eisenhofer et al., 2011, Mannelli et al., 2009, Bausch, Koschker, Fassnacht et al., 2006, Walther, Herring, Enquist et al., 1999).

SDHx: SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD

The succinate dehydrogenase complex is a mitochondrial enzyme complex made up of four subunits encoded by four genes: SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD. The SDHx complex participates in both the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain and plays a key role in regulation of hypoxia inducible factor alpha (HIFα). HIFα activates a variety of target genes resulting in the regulation of apoptosis, angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, energy metabolism, and cellular migration (Favier and Gimenez-Roqueplo, 2010). Inactivating mutations of SDHx genes results in an accumulation of succinate and reactive oxygen free radicals, which can stabilize HIFα and thus activate the hypoxia dependent pathways.

The link between oxidative stress and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma reaches back to the early 1970s. In 1973, Arias-Stella et al. described an association between high altitude and the presence of carotid body tumors (Arias-Stella and Valcarcel, 1973), which was also later correlated with SDHB-related head and neck paragangliomas by Cerecer-Gil et al. in 2010 (Cerecer-Gil, Figuera, Llamas et al., 2010). Another important discovery demonstrating the link between oxidative stress and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma was the demonstration of multiple giant mitochondria and elevation of lactate dehydrogenase activity in an extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Cornog, Wilkinson, Arvan et al., 1970). Giant mitochondria were also later found in SDHB-related renal cell carcinoma (Housley, Lindsay, Young et al., 2010). In 1976 Watanabe et al. demonstrated decreased SDH activity and giant mitochondria in patients with adrenal pheochromocytoma (Watanabe, Burnstock, Jarrott et al., 1976), Heutinik et al. later mapped the gene for hereditary head and neck paraganglioma to 11q (Heutink, van der Mey, Sandkuijl et al., 1992), and finally, in 2000, Baysal et al. discovered the first paraganglioma associated SDHx complex gene: SDHD (11q23) (Baysal, Ferrell, Willett-Brozick et al., 2000). All of these discoveries led to the hypothesis that HIF links mitochondrial dysfunction to development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (King, Selak and Gottlieb, 2006). Mutations in all four genes of the SDHx complex are now known to be associated with the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma though the clinical presentation varies significantly depending on which gene is mutated.

The link between SDHA mutations and pheochromocytoma/paragangliomas was long hypothesized but not proven until 2011. There is still very little data on the clinical features of SDHA-related pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma and it appears that SDHA mutations are not very common. From the data currently available, it appears that these tumors can present in a variety of ways throughout the lifespan. Burnichon et al. reported a case of a 32-year-old female with an extra-adrenal paraganglioma that secreted norepinephrine and normetanephrine (Burnichon, Briere, Libe et al., 2010). Korpershoek et al. later described 6 patients with SDHA mutations whose ages at presentation ranged from 27–77 years and who presented with an adrenal pheochromocytoma (1 patient), extra adrenal paragangliomas (3 patients), or head and neck paragangliomas (2 patients) (Korpershoek, Favier, Gaal et al., 2011). A recent study by Dwight et al. described a 30-year-old male patient with a SDHA mutation who presented with a non-secretory pituitary adenoma that demonstrated loss of SDHA protein expression, similar to that of the patients’ mother who presented with an SDHA-related paraganglioma. This study suggests a potential role of SDHA mutations in the development of other tumors (Dwight, Mann, Benn et al., 2013). More studies are needed to elucidate the specific clinical presentation of SDHA-related pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma.

The clinical presentation of SDHB-related tumors has been much more widely studied and described. Primary tumors most commonly develop in extra-adrenal locations, though adrenal and head and neck primary tumors do occur. The mean age of diagnosis of SDHB-related pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is 30 years of age though it ranges widely from 6 years to 77 years of age. Patients with SDHB-related pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas do not always present with the classic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma symptoms (headache, palpitations, diaphoresis, hypertension) and instead present with symptoms related to mass effect, resulting in a delay in diagnosis that could affect prognostic outcome (Neumann, Pawlu, Peczkowska et al., 2004, Timmers, Kozupa, Eisenhofer et al., 2007, Timmers, Gimenez-Roqueplo, Mannelli et al., 2009, Ricketts, Forman, Rattenberry et al., 2010). When the tumor is secretory, SDHB-related pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are likely to secrete dopamine and/or norepinephrine (Eisenhofer et al., 2011). Increased levels of methoxytyramine has also been associated with SDHB-related disease (Eisenhofer et al., 2011). SDHB-related pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is associated with a high rate of malignancy (reported >30%) with some factors, such as primary tumor development in childhood, being associated with an increased risk for metastatic disease (Neumann et al., 2004, Timmers et al., 2007, Ricketts et al., 2010, King, Prodanov, Kantorovich et al., 2011, Brouwers, Eisenhofer, Tao et al., 2006). SDHB mutations are also known to be associated with an increased risk for development of other tumors such as renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, breast cancer, and papillary thyroid cancer (Ricketts, Woodward, Killick et al., 2008, Pasini, McWhinney, Bei et al., 2008, Lee, Wang, Torbenson et al., 2010). With the associations of these tumors, SDHx related mutations may eventually be considered a metabolic syndrome of sorts. Other syndromes, such as Carney’s triad and Carney-Stratakis dyad, have been described that include the presence of paragangliomas and cases have been associated with SDHB, C and D mutations (Stratakis and Carney, 2009). New syndromes, such as that recently described by Zhuang et al. (Zhuang et al., 2012) (discussed below) may demonstrate a greater link to oxidative stress, including mitochondrial dysfunction, to the development of several tumor types.

SDHC gene mutations are associated with head and neck paragangliomas. The typical age of presentation appears to be around 40–45 years of age. SDHC-related head and neck tumors are not associated with metastatic spread but can be multifocal. These tumors are not classically associated with catecholamine secretion. SDHC-related head and neck tumors are not associated with paternal transmission, unlike SDHD-related head and neck tumors (Schiavi, Boedeker, Bausch et al., 2005, Muller, Troidl and Niemann, 2005, Burnichon, Rohmer, Amar et al., 2009).

SDHD gene mutations predispose patients to development of head and neck paragangliomas. The tumors are often multifocal, bilateral, and recurrent but show a low rate of malignancy. Patients typically present with the tumor in their 30s (Neumann et al., 2004, Ricketts et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2009). Head and neck paragangliomas in general are typically thought to be non-secretory (silent) and while many SDHD-related head and neck paragangliomas are silent, when the tumor does secrete catecholamines it typically secretes dopamine or norepinephrine (Eisenhofer et al., 2011). Interestingly, SDHD mutations exhibit maternal imprinting resulting in disease only with paternal transmission (Ricketts et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2009).

SDHAF2

SDHAF2 encodes the SDHAF2 protein, which is responsible for flavination of SDHA and thus proper functioning of the SDHA subunit (part of the mitochondrial SDHx complex) (Hao, Khalimonchuk, Schraders et al., 2009). Mutations in the SDHAF2 gene result in the rare autosomal dominant syndrome know as familial paraganglioma syndrome 2. These mutations are very rare but when they do occur they predispose individuals to the development of head and neck paragangliomas. These tumors are often multiple and patients tend to present in their 30s. There currently is no indication that SDHAF2 mutations predispose metastatic disease (Hao et al., 2009, Hensen, Siemers, Jansen et al., 2011, Bayley, Kunst, Cascon et al., 2010, van Baars, Cremers, van den Broek et al., 1982, Kunst, Rutten, de Monnink et al., 2011). Based on the current data, it appears that these mutations are paternally transmitted and have high penetrance (Bayley et al., 2010, Kunst et al., 2011).

TMEM127

TMEM127 is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes the TMEM-127 protein. The TMEM-127 protein has been highly conserved throughout evolution and is expressed in various normal tissues and cancer cell lines. Studies suggest TMEM127 is associated with cellular organelles such as the golgi, endosomes, and lysosomes and may play a role in protein trafficking. It has also been suggested that TMEM-127 acts to limit mTORC1 activation (Qin, Yao, King et al., 2010).

Given the recent discovery of TMEM127 mutations predisposing to the development of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas (Qin et al., 2010) more large studies are needed to elucidate the clinical presentation of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma associated TMEM127 mutations. The current literature suggests TMEM127 mutations predispose to metanephrine producing adrenal pheochromocytomas in middle-aged individuals (around 40 years of life). In 2010, Qin et al. reported mutations in the TMEM-127 gene in seven families, 16 patients, with pheochromocytoma (Qin et al., 2010). All 16 patients presented with adrenal pheochromocytomas, approximately 50% of which were bilateral. Following the discovery of a link between TMEM127 mutations and pheochromocytoma several other investigators reported the presence TMEM127 mutations in pheochromocytoma patients (Burnichon, Lepoutre-Lussey, Laffaire et al., 2011, Yao, Schiavi, Cascon et al., 2010, Neumann, Sullivan, Winter et al., 2011). Two studies (Burnichon et al., 2011, Yao et al., 2010) supported the findings of Qin et al., reporting patients presenting around age 40 with adrenal pheochromocytomas that most frequently produced and secreted metanephrine. A study by Neumann et al., however, reported the presence of TMEM127 mutations in a patient with head and neck paragangliomas and another patient with an adrenal pheochromocytoma and an extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Neumann et al., 2011). Very little malignancy with TMEM127 mutations has been reported (Qin et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2011, Yao et al., 2010, Neumann et al., 2011).

MAX

The MAX gene is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes for the MAX protein. MAX is involved in the MYC/MAX/MXD1 complex that is known to be involved in regulating cellular proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Mutation of MAX results in increased cellular proliferation and has been associated with development of pheochromocytomas (Comino-Mendez, Gracia-Aznarez, Schiavi et al., 2011, Peczkowska, Kowalska, Sygut et al., 2013). The current belief is that MAX plays a pivotal role in repressing MYC expression and that in the absence of MAX MYC retains function (Cascon and Robledo, 2012).

Clinically, MAX mutations appear to be most commonly associated with adrenal pheochromocytomas and paternal transmission of MAX mutations has been suggested (Comino-Mendez et al., 2011). The 2011 Comio-Menedez et al. study, that presented the link between MAX mutations and pheochromocytoma for the first time, reported the presence of MAX mutations in 12 patients with adrenal pheochromocytomas (8 bilateral) (Comino-Mendez et al., 2011). Burnichon et al. presented clinical data for 19 patients found to have MAX mutations and reported all presented with adrenal pheochromocytomas at a mean age of 34 years; 13 had bilateral or multiple adrenal tumors, 3 patients had an additional extra-adrenal sympathetic paraganglioma, and 2 patients eventually developed metastatic disease. Overall these tumors may be more frequently metastatic than other hereditary pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas, except those with SDHB/SDHD mutations. Burnichon et al. also reported these tumors were associated mainly with normetanephrine secretion, though some metanephrine secretion was demonstrated, and the tumors had increased expression of PNMT (Burnichon, Cascon, Schiavi et al., 2012). Peczokowska et al. also described a patient who presented with a metanephrine and normetanephrine secreting adrenal pheochromocytoma at 36 years of age and who later developed a recurrence (Peczkowska et al., 2013). Based on these studies, MAX mutations appear to predispose to development of adrenal pheochromocytomas between 30 and 40 years of age with a mixed noradrenergic and adrenergic biochemical phenotype.

PHD2 and H-RAS

The association between PHD2 and HRAS mutations with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma have only been described in a limited number of patients thus far.

The product of the PHD2 gene is a prolyl hydroxylase that is known to function in hydroxylation of HIFα and thus function in the cells response to hypoxia (Ivan, Haberberger, Gervasi et al., 2002). In 2008 Ladroue et al. described a patient with erythrocytosis and abdominal paragangliomas who was found to harbor a mutation in the PHD2 gene (Ladroue, Carcenac, Leporrier et al., 2008). More studies are needed to further characterize the clinical presentation of PHD2-related pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas.

Constitutive RAS signaling is known to increase cell proliferation and induce tumor formation (Adari, Lowy, Willumsen et al., 1988) in several cancers but had not previously been related to the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. Genetic mutations of NF1 and RET are known to affect RAS signaling and are associated with the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma but a mutation to RAS itself predisposing to the development of these tumors was only recently described.

Crona et al. very recently described the presence of H-RAS mutations in a series of 4 male patients, 3 presenting with pheochromocytoma and 1 with an abdominal paraganglioma. The age of diagnosis of disease ranged from 31–76 and biochemical analysis demonstrated a noradrenergic plus adrenergic phenotype in the 3 patients with pheochromocytomas and no measured catecholamine secretion in the patient with an abdominal paraganglioma (patient reportedly presented with hypertensive crisis and died) (Crona et al., 2013). The discovery of this mutation presents a further link between RAS proteins and the development of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. This discovery also highlights the fact that there are still genetic mutations related to pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma yet to be discovered.

HIF2α

Hypoxia-inducible factor is a protein composed of 2 subunits: the constitutively expressed HIFβ subunit and the hypoxia dependent HIFα subunit (Wang, Jiang, Rue et al., 1995). In the presence of oxygen HIFα will be hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylated domain protein 2. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein will then recruit an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that targets HIFα for degradation. Under hypoxic conditions HIFα hydroxylation is suppressed allowing it to heterodimerize with HIFβ and induce various cellular activities including glycolysis, erythropoiesis, and angiogenesis (Kaelin and Ratcliffe, 2008, Hu, Wang, Chodosh et al., 2003, Iyer, Kotch, Agani et al., 1998). Carmeliet et al. demonstrated that HIF1α deficiency stimulates cellular proliferation as opposed to hypoxic growth arrest (Carmeliet et al., 1998). Recently, gain-of-function HIF2α mutations were discovered in several patients with paraganglioma and associated polycythemia (Zhuang et al., 2012) and in vivo and in vitro studies have been performed to support the oncogenic role HIF2α in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (Toledo, Qin, Srikantan et al., 2013).

Several studies have recently been published describing the clinical presentation of paragangliomas developed in the setting of gain-of-function HIF2α mutations. Pacak and Zhaung introduced a new syndrome involving four female patients with polycythemia, multiple duodenal somatostatinomas and multiple extra-adrenal paragangliomas. The women presented with extra-adrenal paragangliomas associated with elevated serum norepinephrine and normetanephrine at relatively young ages: 17 years of age, 18 years of age, 23 years of age, and 25 years of age (Zhuang et al., 2012, Pacak, Jochmanova, Prodanov et al., 2013). Favier et al. described a case of a 24-year-old female who presented with an adrenal pheochromocytoma and was found to have a somatic HIF2α mutation (Favier, Buffet and Gimenez-Roqueplo, 2012). Taieb et al. recently described a case of a 25-year-old female with polycythemia who presented with adrenal and extra-adrenal paragangliomas and was found to have a gain-of-function HIF2α mutation (Taieb, Yang, Delenne et al., 2013). Lorenzo et al. recently described a case of a 35-year-old male with polycythemia who presented with an extra-adrenal paraganglioma progressing to metastatic disease with an associated HIF2α mutation (Lorenzo, Yang, Ng Tang Fui et al., 2013). Comino-Mendez et al. recently described 7 patients with HIF2α mutations, 3 of whom presented with multiple paragangliomas and polycythemia, 1 of whom presented with multiple paragangliomas, 2 of whom presented with solitary pheochromocytomas, and 1 of whom presented with a solitary paraganglioma (Comino-Mendez, de Cubas, Bernal et al., 2013). These findings indicate that HIF2α mutations may be present in the absence of polycythemia. Based on the current findings presented in the literature HIF2α gain-of-function mutations appear to predispose to development of multiple extra-adrenal paragangliomas (multiple pheochromocytomas are much less common) and multiple duodenal somatostatinomas in females with polycythemia development either at birth or in early childhood.

The link between (pseudo) hypoxia and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma has been long hypothesized but it was not until the discovery of the VHL mutation that a true association was made. Over the course of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma research, several hereditary links to the hypoxic pathway and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma have been made: VHL, SDHx, and now, HIF2α. RET and NF1 related tumors are also related to HIF dysfunction in a downstream fashion. While the importance of hypoxia in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma development has long since been hypothesized we may just now be noticing its true impact. As research continues we could see a strong link between HIF and hereditary pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma and this link and knowledge of these pathways has a great potential to impact diagnosis, care, and, possibly, cure of patients.

Current Recommended Cost-Effective Genetic Screening

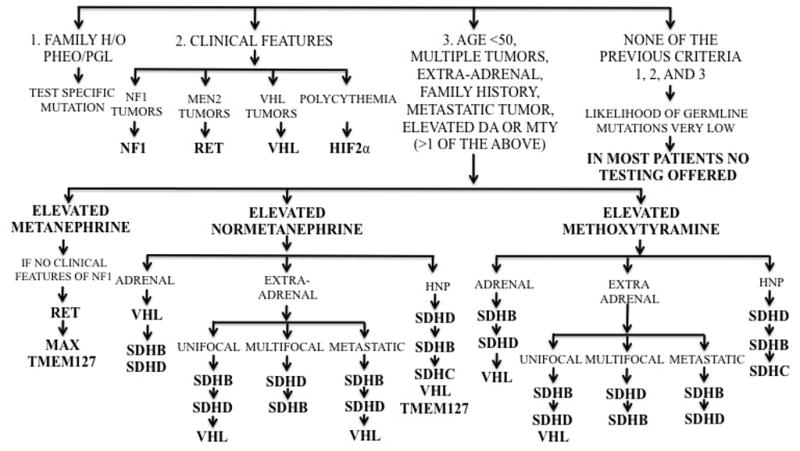

Triaging of genetic screening is extremely important both for guidance of patient care and to avoid excessive cost to any patient. With the advances in genetic screening, determining a patient’s entire genome sequence may one day be cost effective but as of now we must rely on clinical presentation to determine which genetic test to perform first. In absence of a family history of a known mutation, determination of what genetic test to preform depends largely on the patient’s clinical presentation (tumor location and biochemical phenotype) (Figure 1) and immunohistochemical evaluation for the presence of SDHB/A proteins.

Figure 1. Algorithm for gene mutation testing in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma based on clinical presentation and biochemical phenotype.

As indicated by the algorithm, in any patient with a positive family history of a pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma predisposing mutation, that mutation should be tested first. In patients with clinical features indicative of a specific syndrome, the syndromic mutation should be tested first; except in the case of NF1 where the diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation alone. In patients with no family history and without a classic syndromic presentation, determination of which genetic test to preform first depends upon the biochemistry and tumor location. In cases where both normetanephrine and methoxytyramine or metanephrine are elevated use the testing guidance of the latter (methoxytyramine or metanephrine). The biochemical phenotype and most common tumor location for SDHA-related pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma has not yet been elucidated. Patients with head and neck tumor development at a young age with a strong family history of disease should be considered for SDHAF2 genetic testing. Abbreviations: HNP = head and neck paraganglioma. Adapted from Karasek et al.(Karasek, Shah, Frysak et al., 2013)

Tumor Location

Adrenal pheochromocytomas are more commonly associated with VHL (Maher et al., 1990, Delman et al., 2006, Maher et al., 2011, Lonser et al., 2003), RET (Amar et al., 2005, Pacak et al., 2009, Bryant et al., 2003, Lenders et al., 2005), NF1 (Bausch et al., 2006, Walther et al., 1999), TMEM127 (Qin et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2011, Yao et al., 2010, Neumann et al., 2011), or MAX (Comino-Mendez et al., 2011, Peczkowska et al., 2013, Burnichon et al., 2012) gene mutations than with SDHx or HIF2α gene mutations (Mannelli et al., 2009). Extra-adrenal sympathetic paragangliomas are most commonly associated with SDHB mutations (Mannelli et al., 2009, Neumann et al., 2004, Timmers et al., 2007, Timmers et al., 2009, Ricketts et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2009). Head and neck paragangliomas are associated with SDHD (Neumann et al., 2004, Ricketts et al., 2010, Burnichon et al., 2009) (often multiple), SDHC (Schiavi et al., 2005, Muller et al., 2005, Burnichon et al., 2009), SDHAF2, and SDHB (Timmers et al., 2007, Timmers et al., 2009, Ricketts et al., 2010) gene mutations (Mannelli et al., 2009). SDHAF2 mutations should be considered in patients with head and neck paragangliomas, who have a strong family history of head and neck tumors or present at a young age and are negative for other SDHx mutations (Hao et al., 2009, Hensen et al., 2011, Bayley et al., 2010, Kunst et al., 2011).

Biochemical Phenotype

A 2011 study by Eisenhofer et al. expertly helped elucidate the biochemical phenotype of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas related to different genetic mutations. Eisenhofer et al. demonstrated a pattern of metanephrine secretion in RET and NF1-related pheochromocytomas, mainly normetanephrine secretion (some may have also elevated methoxytyramine) in VHL-related tumors, and methoxytyramine secretion (in about 70% of cases), with or without normetanephrine, has been associated with SDHB- and SDHD-related paragangliomas (Eisenhofer et al., 2011). To date, there is no large-scale study on biochemical phenotypes that includes TMEM127, MAX, and HIF2α mutations or SDHB-related adrenal pheochromocytomas. Nevertheless, current evidence from the literature suggests TMEM127-related pheochromocytomas are most commonly associated with metanephrine secretion (Burnichon et al., 2011, Yao et al., 2010), MAX-related pheochromocytomas are more commonly associated with mixed metanephrines and normetanephrine secretion (Burnichon et al., 2012), and HIF2α-related paragangliomas are associated with normetanephrine secretion (Zhuang et al., 2012, Pacak et al., 2013). More studies are needed to properly determine the biochemical phenotype, if any, associated with these genetic mutations but we expect that future studies will confirm the preliminary, but very well carried out, currently available studies.

Presentation

If these tumors are found without any syndromic or familial presentation we recommend that: metastatic tumors to be tested for SDHB mutations; multiple abdominal paragangliomas should be first tested for the presence of SDHD mutations; multiple/bilateral adrenal pheochromocytomas should be tested for TMEM127 mutations; and multiple paragangliomas associated with other neuroendocrine tumors, currently with somatostatinoma, should first be tested for HIF2α mutations.

Histology

Immunohistochemical (IHC) testing with SDHB can also help guide genetic testing. RET, NF1, and VHL-related pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are associated with positive SDHB IHC while SDHx-related pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas are associated with negative SDHB staining (SDHD-related tumors can be weakly positive) (van Nederveen, Gaal, Favier et al., 2009, Gill, Benn, Chou et al., 2010). Negative IHC for SDHA has been correlated with the presence of an SDHA mutation (Korpershoek et al., 2011).

Implications

Knowledge of a patients’ mutation status can be very important in guiding treatment and follow up care. As previously mentioned, many of the genetic mutations discussed are associated with tumors and findings other than pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma that need to be followed. Prophylactic thyroidectomy, for example, is recommended for patients with specific RET mutations (Moore, Appfelstaedt and Zaahl, 2007, Kloos, Eng, Evans et al., 2009). Certain genetic mutations are more likely to predispose to metastatic disease than others and must be followed accordingly. Patients with SDHB mutations should be followed closely by both biochemistry and serial imaging for development of metastatic disease, especially those who presented with their primary tumor at a young age. Multiple studies have shown that certain imaging modalities work better in certain subsets of patients, for example 18F-FDG PET imaging is recommended for follow up and screening of all SHDB-related metastatic tumors (Timmers, Kozupa, Chen et al., 2007) while 18F-FDOPA PET imaging may be most accurate for imaging of head and neck tumor regardless of their genetic status (King, Whatley, Alexopoulos et al., 2010, Gabriel, Blanchet, Sebag et al., 2012). Additionally, knowledge of the genetics of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma has led to developments that have improved our understanding of the disease process as a whole. For example, the development of the mouse pheochromocytoma cell line (MPC) from NF1 (Powers, Evinger, Tsokas et al., 2000), and the more aggressive mouse tumor tissue (Martiniova, Lai, Elkahloun et al., 2009), have greatly improved and eased our ability to study pheochromocytoma signaling pathways as well as test new imaging modalities (Martiniova, Perera, Brouwers et al., 2011, Martiniova, Ohta, Guion et al., 2006, Martiniova, Cleary, Lai et al., 2012).

Recent advances in genetics have caused a shift from a tumor defined by the “rule of 10s” to a “10-gene tumor” and now to a tumor defined by a multitude of genetic mutations with various clinical presentations. The links between signaling pathways are becoming more apparent and, perhaps one day may lead to a discovery that all hereditary pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas associate with a common signaling pathway or molecule. Knowledge of these genetic mutations and associated clinical presentations greatly assists in patient care. Despite our current knowledge, there is still much to learn about this disease. There are likely more pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma related genes yet to be discovered, such as a gene associated with the large percentage of metastatic pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas that are currently considered sporadic. As more research is done and more associations are made our understanding of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas may eventually evolve to the point of finding a cure or, at the very least, advancement of more efficacious and specific therapeutic options in the future.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical presentations of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma associated with various genetic mutations.

| Gene | Age at Primary Diagnosis | Primary Tumor Location | Biochemical Phenotype | Metastatic Potential | Some Other Tumors and Important Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHL | 30s | Adrenal (bilateral) | NE or NE & DA | Low | Retinal hemangiomas, CNS hemangioblastomas, clear cell renal carcinoma |

| RET | 30s | Adrenal (bilateral) | EPI or EPI & NE | Low | Medullary thyroid cancer, hyperparathyroidism, marphanoid habitus, mucosal ganglioneuromas |

| NF1 | 40s | Adrenal | EPI or EPI & NE | Low | Caf -au-lait spots, neurofibromas, medullary thyroid cancer, carcinoid tumors, peripheral nerve sheath tumors |

| SDHA | 27–77 | Head and neck, adrenal, extra-adrenal | ? | ? | Clear cell renal carcinoma, GIST, pituitary adenoma |

| SDHB | 30s | Extra-adrenal | NE or DA or NE & DA or nonsecretory | High | Clear cell renal carcinoma, GIST, pituitary adenoma, breast and thyroid cancer (?), neuroblastoma pulmonary chondroma |

| SDHC | 40s | Head and neck | NE or nonsecretory | Low | Clear cell renal carcinoma |

| SDHD | 30s | Head and neck (bilateral, multifocal) or extra-adrenal | NE or DA or NE & DA or nonsecretory | Low | Clear cell renal carcinoma, GIST, pituitary adenoma, pulmonary chondroma |

| SDHAF2 | 30s | Head and neck (multiple) | ? | Low | None Known |

| TMEM127 | 40s | Adrenal (bilateral) | EPI? | Low | None Known |

| MAX | 30s | Adrenal (bilateral) | NE & EPI | Moderate | None Known |

| HRAS | 31–76 | Adrenal | NE or EPI | Low | None Known |

| HIF2α | 17–35 | Extra-adrenal | NE | Low | Polycythemia, somatostatinoma |

Abbreviations: DA = dopamine, CNS = central nervous system, EPI = epinephrine, GIST = Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, NE = norepinephrine.

Highlights.

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are now known to be associated with 13 susceptibility genes

Genetic testing can be triaged based on the individual patients clinical presentation

Knowledge of genetic mutations allows for individualized care

Research on the molecular actions of these genes will lead to greater understanding of this disease

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Crona J, Delgado Verdugo A, Maharjan R, Stalberg P, Granberg D, Hellman P, Bjorklund P. Somatic Mutations in H-RAS in Sporadic Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Identified by Exome Sequencing. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z, Yang C, Lorenzo F, Merino M, Fojo T, Kebebew E, Popovic V, Stratakis CA, Prchal JT, Pacak K. Somatic HIF2A gain-of-function mutations in paraganglioma with polycythemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:922–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar L, Bertherat J, Baudin E, Ajzenberg C, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Chabre O, Chamontin B, Delemer B, Giraud S, Murat A, Niccoli-Sire P, Richard S, Rohmer V, Sadoul JL, Strompf L, Schlumberger M, Bertagna X, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Genetic testing in pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8812–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Burnichon N, Amar L, Favier J, Jeunemaitre X, Plouin PF. Recent advances in the genetics of phaeochromocytoma and functional paraganglioma. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:376–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Vescovo L, Amar L, Libe R, de Reynies A, Venisse A, Jouanno E, Laurendeau I, Parfait B, Bertherat J, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Integrative genomic analysis reveals somatic mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20:3974–85. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Huynh TT, Pacak K, Brouwers FM, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Munson PJ, Mannelli M, Goldstein DS, Elkahloun AG. Distinct gene expression profiles in norepinephrine- and epinephrine-producing hereditary and sporadic pheochromocytomas: activation of hypoxia-driven angiogenic pathways in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:897–911. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia PL, Ross KN, Wright ME, Hayashida CY, Santagata S, Barontini M, Kung AL, Sanso G, Powers JF, Tischler AS, Hodin R, Heitritter S, Moore F, Dluhy R, Sosa JA, Ocal IT, Benn DE, Marsh DJ, Robinson BG, Schneider K, Garber J, Arum SM, Korbonits M, Grossman A, Pigny P, Toledo SP, Nose V, Li C, Stiles CD. A HIF1alpha regulatory loop links hypoxia and mitochondrial signals in pheochromocytomas. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:72–80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Jimenez E, Gomez-Lopez G, Leandro-Garcia LJ, Munoz I, Schiavi F, Montero-Conde C, de Cubas AA, Ramires R, Landa I, Leskela S, Maliszewska A, Inglada-Perez L, de la Vega L, Rodriguez-Antona C, Leton R, Bernal C, de Campos JM, Diez-Tascon C, Fraga MF, Boullosa C, Pisano DG, Opocher G, Robledo M, Cascon A. Research resource: Transcriptional profiling reveals different pseudohypoxic signatures in SDHB and VHL-related pheochromocytomas. Molecular Endocrinology. 2010;24:2382–91. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–5. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, Koch CJ, Ratcliffe P, Moons L, Jain RK, Collen D, Keshert E. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394:485–90. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JH, Yang H, Ivan M, Gertler F, Kaelin WG, Jr, Pavletich NP. Structure of an HIF-1alpha -pVHL complex: hydroxyproline recognition in signaling. Science. 2002;296:1886–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1073440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, Benjamin C, Harris R, Moore AT, Ferguson-Smith MA. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77:1151–63. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, Patronas NJ, Linehan WM, Zbar B. von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology. 1995;194:629–42. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Kishida T, Yao M, Hustad T, Glavac D, Dean M, Gnarra J, Orcutt M, Duh F, Glenn G, Green J, Hsia Y, Lamiell J, Li H, Wei M, Schmidt L, Tory K, Kuzmin I, Stackhouse T, Latif F, Linehan W, Lerman M, Zbar B. Germline mutations in the von hippel-lindau disease tumor suppressor gene: correlation with phenotype. Human Mutation. 1995;5:66–75. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delman KA, Shapiro SE, Jonasch EW, Lee JE, Curley SA, Evans DB, Perrier ND. Abdominal visceral lesions in von Hippel-Lindau disease: incidence and clinical behavior of pancreatic and adrenal lesions at a single center. World Journal of Surgery. 2006;30:665–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher ER, Neumann HP, Richard S. von Hippel-Lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;19:617–23. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Lenders JW, Timmers H, Mannelli M, Grebe SK, Hofbauer LC, Bornstein SR, Tiebel O, Adams K, Bratslavsky G, Linehan WM, Pacak K. Measurements of plasma methoxytyramine, normetanephrine, and metanephrine as discriminators of different hereditary forms of pheochromocytoma. Clinical Chemistry. 2011;57:411–20. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.153320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M, Carlomagno F, Romano A, Bottaro DP, Dathan NA, Grieco M, Fusco A, Vecchio G, Matoskova B, Kraus MH, et al. Activation of RET as a dominant transforming gene by germline mutations of MEN2A and MEN2B. Science. 1995;267:381–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7824936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Raue K, Kratt T, Hoppner W, Buhr H, Ziegler R, Raue F. Diagnosis and management of pheochromocytomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2-relevance of specific mutations in the RET proto-oncogene. Eur J Endocrinol. 1996;135:222–5. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe JR, Norton JA, Wells SA., Jr Prevalence of pheochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A: results of long-term follow-up. Surgery. 1993;114:1070–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauckhoff M, Machens A, Hess S, Lorenz K, Gimm O, Brauckhoff K, Sekulla C, Dralle H. Premonitory symptoms preceding metastatic medullary thyroid cancer in MEN 2B: An exploratory analysis. Surgery. 2008;144:1044–50. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.028. discussion 1050–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohllk N, Schweizer H, Erlic Z, Schmid KW, Walz MK, Raue F, Neumann HP. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:371–87. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Ilias I. Diagnosis of pheochromocytoma with special emphasis on MEN2 syndrome. Hormones (Athens) 2009;8:111–6. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannelli M, Castellano M, Schiavi F, Filetti S, Giacche M, Mori L, Pignataro V, Bernini G, Giache V, Bacca A, Biondi B, Corona G, Di Trapani G, Grossrubatscher E, Reimondo G, Arnaldi G, Giacchetti G, Veglio F, Loli P, Colao A, Ambrosio MR, Terzolo M, Letizia C, Ercolino T, Opocher G. Clinically guided genetic screening in a large cohort of italian patients with pheochromocytomas and/or functional or nonfunctional paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1541–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J, Farmer J, Kessler LJ, Townsend RR, Nathanson KL. Pheochromocytoma: the expanding genetic differential diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1196–204. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen CM, Reczek EE, James MF, Brems H, Legius E, Cichowski K. The NF1 tumor suppressor critically regulates TSC2 and mTOR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:8573–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503224102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Neurofibromatosis; Consensus Development Conference Statement: neurofibromatosis; Bethesda, Md., USA. July 13–15, 1987; pp. 172–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoller ME, Rembeck B, Oden A, Samuelsson M, Angervall L. Malignant and benign tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a defined Swedish population. Cancer. 1997;79:2125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: past, present, and future. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1283–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105023241812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausch B, Koschker AC, Fassnacht M, Stoevesandt J, Hoffmann MM, Eng C, Allolio B, Neumann HP. Comprehensive mutation scanning of NF1 in apparently sporadic cases of pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3478–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther MM, Herring J, Enquist E, Keiser HR, Linehan WM. von Recklinghausen’s disease and pheochromocytomas. J Urol. 1999;162:1582–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Pheochromocytomas: The (pseudo)-hypoxia hypothesis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:957–68. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Stella J, Valcarcel J. The human carotid body at high altitudes. Pathologia et Microbiologia. 1973;39:292–7. doi: 10.1159/000162666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerecer-Gil NY, Figuera LE, Llamas FJ, Lara M, Escamilla JG, Ramos R, Estrada G, Hussain AK, Gaal J, Korpershoek E, de Krijger RR, Dinjens WN, Devilee P, Bayley JP. Mutation of SDHB is a cause of hypoxia-related high-altitude paraganglioma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:4148–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornog JL, Wilkinson JH, Arvan DA, Freed RM, Sellers AM, Barker C. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. Some electron microscopic and biochemical studies. American Journal of Medicine. 1970;48:654–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(70)90018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley SL, Lindsay RS, Young B, McConachie M, Mechan D, Baty D, Christie L, Rahilly M, Qureshi K, Fleming S. Renal carcinoma with giant mitochondria associated with germ-line mutation and somatic loss of the succinate dehydrogenase B gene. Histopathology. 2010;56:405–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Burnstock G, Jarrott B, Louis WJ. Mitochondrial abnormalities in human phaeochromocytoma. Cell and Tissue Research. 1976;172:281–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00226032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heutink P, van der Mey AG, Sandkuijl LA, van Gils AP, Bardoel A, Breedveld GJ, van Vliet M, van Ommen GJ, Cornelisse CJ, Oostra BA, et al. A gene subject to genomic imprinting and responsible for hereditary paragangliomas maps to chromosome 11q23-qter. Human Molecular Genetics. 1992;1:7–10. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Myssiorek D, Bosch A, van der Mey A, Taschner PE, Rubinstein WS, Myers EN, Richard CW, 3rd, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P, Devlin B. Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science. 2000;287:848–51. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, Selak MA, Gottlieb E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:4675–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Briere JJ, Libe R, Vescovo L, Riviere J, Tissier F, Jouanno E, Jeunemaitre X, Benit P, Tzagoloff A, Rustin P, Bertherat J, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. SDHA is a tumor suppressor gene causing paraganglioma. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19:3011–20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek E, Favier J, Gaal J, Burnichon N, van Gessel B, Oudijk L, Badoual C, Gadessaud N, Venisse A, Bayley JP, van Dooren MF, de Herder WW, Tissier F, Plouin PF, van Nederveen FH, Dinjens WN, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, de Krijger RR. SDHA immunohistochemistry detects germline SDHA gene mutations in apparently sporadic paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:E1472–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight T, Mann K, Benn DE, Robinson BG, McKelvie P, Gill AJ, Winship I, Clifton-Bligh RJ. Familial SDHA Mutation Associated With Pituitary Adenoma and Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, Bausch B, McWhinney SR, Muresan M, Buchta M, Franke G, Klisch J, Bley TA, Hoegerle S, Boedeker CC, Opocher G, Schipper J, Januszewicz A, Eng C. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292:943–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Kozupa A, Eisenhofer G, Raygada M, Adams KT, Solis D, Lenders JW, Pacak K. Clinical presentations, biochemical phenotypes, and genotype-phenotype correlations in patients with succinate dehydrogenase subunit B-associated pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:779–86. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Clinical aspects of SDHx-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:391–400. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts CJ, Forman JR, Rattenberry E, Bradshaw N, Lalloo F, Izatt L, Cole TR, Armstrong R, Kumar VK, Morrison PJ, Atkinson AB, Douglas F, Ball SG, Cook J, Srirangalingam U, Killick P, Kirby G, Aylwin S, Woodward ER, Evans DG, Hodgson SV, Murday V, Chew SL, Connell JM, Blundell TL, Macdonald F, Maher ER. Tumor risks and genotype-phenotype-proteotype analysis in 358 patients with germline mutations in SDHB and SDHD. Human Mutation. 2010;31:41–51. doi: 10.1002/humu.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KS, Prodanov T, Kantorovich V, Fojo T, Hewitt JK, Zacharin M, Wesley R, Lodish M, Raygada M, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, McCormack S, Eisenhofer G, Milosevic D, Kebebew E, Stratakis CA, Pacak K. Metastatic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma related to primary tumor development in childhood or adolescence: significant link to SDHB mutations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4137–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers FM, Eisenhofer G, Tao JJ, Kant JA, Adams KT, Linehan WM, Pacak K. High Frequency of SDHB Germline Mutations in Patients with Malignant Catecholamine-Producing Paragangliomas: Implications for Genetic Testing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4505–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P, Morris MR, Astuti D, Latif F, Maher ER. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1260–2. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, Matyakhina L, Stergiopoulos S, Muchow M, Boikos SA, Ferrando B, Pacak K, Assie G, Baudin E, Chompret A, Ellison JW, Briere JJ, Rustin P, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Eng C, Carney JA, Stratakis CA. Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:79–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Wang J, Torbenson M, Lu Y, Liu QZ, Li S. Loss of SDHB and NF1 genes in a malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast as detected by oligo-array comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2010;196:179–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis CA, Carney JA. The triad of paragangliomas, gastric stromal tumours and pulmonary chondromas (Carney triad), and the dyad of paragangliomas and gastric stromal sarcomas (Carney-Stratakis syndrome): molecular genetics and clinical implications. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2009;266:43–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavi F, Boedeker CC, Bausch B, Peczkowska M, Gomez CF, Strassburg T, Pawlu C, Buchta M, Salzmann M, Hoffmann MM, Berlis A, Brink I, Cybulla M, Muresan M, Walter MA, Forrer F, Valimaki M, Kawecki A, Szutkowski Z, Schipper J, Walz MK, Pigny P, Bauters C, Willet-Brozick JE, Baysal BE, Januszewicz A, Eng C, Opocher G, Neumann HP. Predictors and prevalence of paraganglioma syndrome associated with mutations of the SDHC gene. Jama. 2005;294:2057–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Troidl C, Niemann S. SDHC mutations in hereditary paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:9–12. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-0621-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Rohmer V, Amar L, Herman P, Leboulleux S, Darrouzet V, Niccoli P, Gaillard D, Chabrier G, Chabolle F, Coupier I, Thieblot P, Lecomte P, Bertherat J, Wion-Barbot N, Murat A, Venisse A, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. The succinate dehydrogenase genetic testing in a large prospective series of patients with paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2817–27. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao HX, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, Dephoure N, Bayley JP, Kunst H, Devilee P, Cremers CW, Schiffman JD, Bentz BG, Gygi SP, Winge DR, Kremer H, Rutter J. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science. 2009;325:1139–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1175689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensen EF, Siemers MD, Jansen JC, Corssmit EP, Romijn JA, Tops CM, van der Mey AG, Devilee P, Cornelisse CJ, Bayley JP, Vriends AH. Mutations in SDHD are the major determinants of the clinical characteristics of Dutch head and neck paraganglioma patients. Clinical Endocrinology. 2011;75:650–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley JP, Kunst HP, Cascon A, Sampietro ML, Gaal J, Korpershoek E, Hinojar-Gutierrez A, Timmers HJ, Hoefsloot LH, Hermsen MA, Suarez C, Hussain AK, Vriends AH, Hes FJ, Jansen JC, Tops CM, Corssmit EP, de Knijff P, Lenders JW, Cremers CW, Devilee P, Dinjens WN, de Krijger RR, Robledo M. SDHAF2 mutations in familial and sporadic paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:366–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baars F, Cremers C, van den Broek P, Geerts S, Veldman J. Genetic aspects of nonchromaffin paraganglioma. Hum Genet. 1982;60:305–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00569208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst HP, Rutten MH, de Monnink JP, Hoefsloot LH, Timmers HJ, Marres HA, Jansen JC, Kremer H, Bayley JP, Cremers CW. SDHAF2 (PGL2-SDH5) and hereditary head and neck paraganglioma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:247–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Yao L, King EE, Buddavarapu K, Lenci RE, Chocron ES, Lechleiter JD, Sass M, Aronin N, Schiavi F, Boaretto F, Opocher G, Toledo RA, Toledo SP, Stiles C, Aguiar RC, Dahia PL. Germline mutations in TMEM127 confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:229–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Lepoutre-Lussey C, Laffaire J, Gadessaud N, Molinie V, Hernigou A, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. A novel TMEM127 mutation in a patient with familial bilateral pheochromocytoma. European Journal of Endocrinology/European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2011;164:141–5. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Schiavi F, Cascon A, Qin Y, Inglada-Perez L, King EE, Toledo RA, Ercolino T, Rapizzi E, Ricketts CJ, Mori L, Giacche M, Mendola A, Taschin E, Boaretto F, Loli P, Iacobone M, Rossi GP, Biondi B, Lima-Junior JV, Kater CE, Bex M, Vikkula M, Grossman AB, Gruber SB, Barontini M, Persu A, Castellano M, Toledo SP, Maher ER, Mannelli M, Opocher G, Robledo M, Dahia PL. Spectrum and prevalence of FP/TMEM127 gene mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. JAMA. 2010;304:2611–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Sullivan M, Winter A, Malinoc A, Hoffmann MM, Boedeker CC, Bertz H, Walz MK, Moeller LC, Schmid KW, Eng C. Germline mutations of the TMEM127 gene in patients with paraganglioma of head and neck and extraadrenal abdominal sites. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:E1279–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comino-Mendez I, Gracia-Aznarez FJ, Schiavi F, Landa I, Leandro-Garcia LJ, Leton R, Honrado E, Ramos-Medina R, Caronia D, Pita G, Gomez-Grana A, de Cubas AA, Inglada-Perez L, Maliszewska A, Taschin E, Bobisse S, Pica G, Loli P, Hernandez-Lavado R, Diaz JA, Gomez-Morales M, Gonzalez-Neira A, Roncador G, Rodriguez-Antona C, Benitez J, Mannelli M, Opocher G, Robledo M, Cascon A. Exome sequencing identifies MAX mutations as a cause of hereditary pheochromocytoma. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:663–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peczkowska M, Kowalska A, Sygut J, Waligorski D, Malinoc A, Janaszek-Sitkowska H, Prejbisz A, Januszewicz A, Neumann HP. Testing new susceptibility genes in the cohort of apparently sporadic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma patients with clinical characteristics of hereditary syndromes. Clinical Endocrinology. 2013 doi: 10.1111/cen.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascon A, Robledo M. MAX and MYC: a heritable breakup. Cancer Research. 2012;72:3119–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Cascon A, Schiavi F, Morales NP, Comino-Mendez I, Abermil N, Inglada-Perez L, de Cubas AA, Amar L, Barontini M, de Quiros SB, Bertherat J, Bignon YJ, Blok MJ, Bobisse S, Borrego S, Castellano M, Chanson P, Chiara MD, Corssmit EP, Giacche M, de Krijger RR, Ercolino T, Girerd X, Gomez-Garcia EB, Gomez-Grana A, Guilhem I, Hes FJ, Honrado E, Korpershoek E, Lenders JW, Leton R, Mensenkamp AR, Merlo A, Mori L, Murat A, Pierre P, Plouin PF, Prodanov T, Quesada-Charneco M, Qin N, Rapizzi E, Raymond V, Reisch N, Roncador G, Ruiz-Ferrer M, Schillo F, Stegmann AP, Suarez C, Taschin E, Timmers HJ, Tops CM, Urioste M, Beuschlein F, Pacak K, Mannelli M, Dahia PL, Opocher G, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Robledo M. MAX mutations cause hereditary and sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18:2828–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M, Haberberger T, Gervasi DC, Michelson KS, Gunzler V, Kondo K, Yang H, Sorokina I, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Kaelin WG., Jr Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:13459–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192342099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladroue C, Carcenac R, Leporrier M, Gad S, Le Hello C, Galateau-Salle F, Feunteun J, Pouyssegur J, Richard S, Gardie B. PHD2 mutation and congenital erythrocytosis with paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2685–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adari H, Lowy DR, Willumsen BM, Der CJ, McCormick F. Guanosine triphosphatase activating protein (GAP) interacts with the p21 ras effector binding domain. Science. 1988;240:518–21. doi: 10.1126/science.2833817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:5510–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Molecular Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23:9361–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, Semenza GL. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes and Development. 1998;12:149–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo RA, Qin Y, Srikantan S, Morales NP, Li Q, Deng Y, Kim S, Pereira MA, Toledo SP, Su X, Aguiar RC, Dahia P. In vivo and in vitro oncogenic effects of HIF2A mutations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak K, Jochmanova I, Prodanov T, Yang C, Merino MJ, Fojo T, Prchal JT, Tischler AS, Lechan RM, Zhuang Z. New Syndrome of Paraganglioma and Somatostatinoma Associated With Polycythemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier J, Buffet A, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. HIF2A mutations in paraganglioma with polycythemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:2161. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1211953. author reply 2161–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taieb D, Yang C, Delenne B, Zhuang Z, Barlier A, Sebag F, Pacak K. First Report of Bilateral Pheochromocytoma in the Clinical Spectrum of HIF2A-Related Polycythemia-Paraganglioma Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo FR, Yang C, Ng Tang Fui M, Vankayalapati H, Zhuang Z, Huynh T, Grossmann M, Pacak K, Prchal JT. A novel EPAS1/HIF2A germline mutation in a congenital polycythemia with paraganglioma. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:507–12. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0967-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comino-Mendez I, de Cubas AA, Bernal C, Alvarez-Escola C, Sanchez-Malo C, Ramirez-Tortosa CL, Pedrinaci S, Rapizzi E, Ercolino T, Bernini G, Bacca A, Leton R, Pita G, Alonso MR, Leandro-Garcia LJ, Gomez-Grana A, Inglada-Perez L, Mancikova V, Rodriguez-Antona C, Mannelli M, Robledo M, Cascon A. Tumoral EPAS1 (HIF2A) mutations explain sporadic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in the absence of erythrocytosis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013;22:2169–76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nederveen FH, Gaal J, Favier J, Korpershoek E, Oldenburg RA, de Bruyn EM, Sleddens HF, Derkx P, Riviere J, Dannenberg H, Petri BJ, Komminoth P, Pacak K, Hop WC, Pollard PJ, Mannelli M, Bayley JP, Perren A, Niemann S, Verhofstad AA, de Bruine AP, Maher ER, Tissier F, Meatchi T, Badoual C, Bertherat J, Amar L, Alataki D, Van Marck E, Ferrau F, Francois J, de Herder WW, Peeters MP, van Linge A, Lenders JW, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, de Krijger RR, Dinjens WN. An immunohistochemical procedure to detect patients with paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma with germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:764–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, Clarkson A, Muljono A, Meyer-Rochow GY, Richardson AL, Sidhu SB, Robinson BG, Clifton-Bligh RJ. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD in paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Human Pathology. 2010;41:805–14. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SW, Appfelstaedt J, Zaahl MG. Familial medullary carcinoma prevention, risk evaluation, and RET in children of families with MEN2. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, Francis GL, Gagel RF, Gharib H, Moley JF, Pacini F, Ringel MD, Schlumberger M, Wells SA., Jr Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2009;19:565–612. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HJ, Kozupa A, Chen CC, Carrasquillo JA, Ling A, Eisenhofer G, Adams KT, Solis D, Lenders JW, Pacak K. Superiority of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to other functional imaging techniques in the evaluation of metastatic SDHB-associated pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2262–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KS, Whatley MA, Alexopoulos DK, Reynolds JC, Chen CC, Mattox DE, Jacobs S, Pacak K. The use of functional imaging in a patient with head and neck paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:481–2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Blanchet EM, Sebag F, Chen CC, Fakhry N, Deveze A, Barlier A, Morange I, Pacak K, Taieb D. Functional characterization of nonmetastatic paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma by F-FDOPA PET: focus on missed lesions. Clinical Endocrinology. 2012 doi: 10.1111/cen.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JF, Evinger MJ, Tsokas P, Bedri S, Alroy J, Shahsavari M, Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma cell lines from heterozygous neurofibromatosis knockout mice. Cell and Tissue Research. 2000;302:309–20. doi: 10.1007/s004410000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniova L, Lai EW, Elkahloun AG, Abu-Asab M, Wickremasinghe A, Solis DC, Perera SM, Huynh TT, Lubensky IA, Tischler AS, Kvetnansky R, Alesci S, Morris JC, Pacak K. Characterization of an animal model of aggressive metastatic pheochromocytoma linked to a specific gene signature. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 2009;26:239–50. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9236-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniova L, Perera SM, Brouwers FM, Alesci S, Abu-Asab M, Marvelle AF, Kiesewetter DO, Thomasson D, Morris JC, Kvetnansky R, Tischler AS, Reynolds JC, Fojo AT, Pacak K. Increased uptake of [(1)(2)(3)I]meta-iodobenzylguanidine, [(1)F]fluorodopamine, and [(3)H]norepinephrine in mouse pheochromocytoma cells and tumors after treatment with the histone deacetylase inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:143–57. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniova L, Ohta S, Guion P, Schimel D, Lai EW, Klaunberg B, Jagoda E, Pacak K. Anatomical and functional imaging of tumors in animal models: focus on pheochromocytoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:392–404. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniova L, Cleary S, Lai EW, Kiesewetter DO, Seidel J, Dawson LF, Phillips JK, Thomasson D, Chen X, Eisenhofer G, Powers JF, Kvetnansky R, Pacak K. Usefulness of [18F]-DA and [18F]-DOPA for PET imaging in a mouse model of pheochromocytoma. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2012;39:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek D, Shah U, Frysak Z, Stratakis C, Pacak K. An update on the genetics of pheochromocytoma. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2013;27:141–7. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]