Abstract

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) transgenic mice (Tg) were created using a rat HO-1 genomic transgene. Transgene expression was detected by RT-PCR and Western blots in the left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV) and septum (S) in mouse hearts, and its function was demonstrated by the elevated HO enzyme activity. Tg and non-transgenic (NTg) mouse hearts were isolated and subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. Significant post-ischemic recovery in coronary flow (CF), aortic flow (AF), aortic pressure (AOP) and first derivative of AOP (AOPdp/dt) were detected in the HO-1 Tg group compared to the NTg values. In HO-1 Tg hearts treated with 50 μmol/kg of tin protoporphyrin IX (SnPPIX), an HO enzyme inhibitor, abolished the post-ischemic cardiac recovery. HO-1 related carbon monoxide (CO) production was detected in NTg, HO-1 Tg and HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX treated groups, and a substantial increase in CO production was observed in the HO-1 Tg hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. Moreover, in ischemia/reperfusion-induced tissue Na+ and Ca2+ gains were reduced in HO-1 Tg group in comparison with the NTg and HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX treated groups; furthermore K+ loss was reduced in the HO-1 Tg group. The infarct size was markedly reduced from its NTg control value of 37 ± 4% to 20 ± 6% (P < 0.05) in the HO-1 Tg group, and was increased to 47 ± 5% (P < 0.05) in the HO-1 knockout (KO) hearts. Parallel to the infarct size reduction, the incidence of total and sustained ventricular fibrillation were also reduced from their NTg control values of 92% and 83% to 25% (P < 0.05) and 8% (P < 0.05) in the HO-1 Tg group, and were increased to 100% and 100% in HO-1 KO−/− hearts. Immunohistochemical staining of HO-1 was intensified in HO-1 Tg compared to the NTg myocardium. Thus, the HO-1 Tg mouse model suggests a valuable therapeutic approach in the treatment of ischemic myocardium.

Keywords: heme oxygenase-1, ischemia, reperfusion

Introduction

With respect to gene control and regulation, a great number of inducer-responsive elements have been identified and characterized within the 5′-flanking regions of the mouse, rat and human heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). In the past decades, substantial progress has been made in our understanding of the regulation and function of HO-1 and its isozymes. Thus, heat shock proteins including HO-1, known as 32 kD stress-inducible protein, provides significant protection against a variety of tissue injuries [1]. Different isozymes of HO have been identified, cloned and studies demonstrated that HO-1 is induced in response to various interventions causing oxidative stress including ultraviolet irradiation, hypoxia and ischemia [2–6]. By degrading oxidant heme and generating antioxidant bilirubin, and a gaseous molecule, endogen carbon monoxide (CO), and HO-1 induction protect tissues from death caused by various pathological processes [7–10]. Thus, in various diseases that are induced by different factors, the lack of HO-1 or its expression substantially modifies tissue and organ functions. Given the cytoprotective role of HO-1, there is a growing interest in the importance of HO-1 and its by-products, e.g. iron and endogenous CO, in the recovery of cardiac injury caused by ischemia [11, 12].

In our previous studies, we observed a reduction in HO-1 mRNA and protein expression causing decreased enzyme activity leading ultimately to poor recovery of the ischemic/reperfused fibrillated myocardium [13, 14]. To conclusively demonstrate whether HO-1 plays a critical role in the recovery of post-ischemic myocardium, we generated HO-1 transgenic mice (Tg). We suggested that the vulnerability of HO-1 Tg to reduce the incidence of ventricular fibrillation (VF), attenuation of infarct size and improved recovery of post-ischemic function during ischemia/reperfusion injury would be related to HO-1 protein expression and its by-products including the endogenous CO or iron. We also speculated that HO-1 signalling and protein expression would play an essential role in the improvement post-ischemic cardiac aortic flow (AF), coronary flow (CF), aortic pressure (AOP), the first derivative of AOP (AOPdp/dt), myocardial ion contents including Na+, K+ and Ca2+. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the post-ischemic recovery and the causes of arrhythmias, but relatively little attention has been paid, to our knowledge, in order to clarify the mechanism(s) of VF at a gene expression level in ischemic/reperfused hearts. For instance, the long QT syndrome and idiopathic VF, as known until now, are cardiac disorders based on genetic mutation of potassium channels and cause sudden cardiac death from ventricular arrhythmias [15–17]. The aim of our present study was to generate and use HO-1 Tg to directly analyse the impact and role of HO-1 on post-ischemic recovery in the myocardium. In some additional studies, we made attempt to estimate the incidence of reperfusion-induced VF and infarct size in HO-1 Tg mouse heart in comparison with HO-1 knockout (KO)−/− and wild-type mouse myocardium. We believe that the present study provides novel insights into the function of HO-1 and its contribution to the recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function and reduction of arrhythmias in the heart.

Methods

Transgenic mice

Tg were generated as described by Araujo et al. [9]. In brief, CFY mouse eggs were injected with 52 kb rat HO-1 construct containing 27.7 kb of the 5′ upstream region, 8.3 kb of HO-1 gene and 16 kb of the 3′ downstream region. Cloning was carried out by PCR of rat genomic P1 library with two sets of PCR primers corresponding to the first exon (5′-GCT-TCG-GTG-GGT-TAT-CTG-CCG-TTA-T-3′ and 5′-CAG-TCT-TAC-AGG-CGG-GGA-ATG-TGA-G-3′), and the fifth exon of rat HO-1 gene (5′-GAG-ACG-CCC-CGA-GGA-AAA-TCC-CAG-AT-3′ and 5′-CCC-AAG-AAA-AGA-GAG-CCA-GGC-AAG-AT-3′). Two clones were identified as positives, and restriction mapping showed that both of them included the same insert. The 52 kb band was equivalent to the HO-1 gene and flanking regions. This 52 kb fragment, including the native HO-1 gene and its promoter, was excised and digested with β-agarase, and then microinjected. Mice were genotyped by PCR using the set of primers specific for rat HO-1 exon 5.

Animals and heart preparation

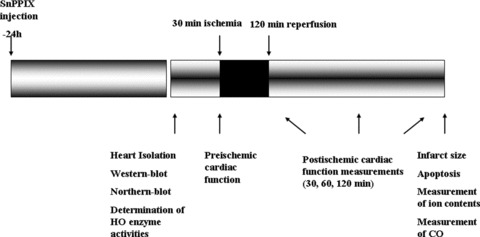

Male wild-type (non-transgenic, NTg), HO-1 Tg and HO-1 KO−/− mice (25–35 g) (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany), were used for all studies. Animals received humane care in compliance with the ‘Principles of Laboratory Animal Care’, formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institute of Health (NIH Publication No. 86–23, revised 1996). Mice were anaesthetized with 60 mg/kg of pentobarbital sodium. After i.p. administration of heparin (1000 IU/kg) the chest was opened, the heart was rapidly excised and mounted to a ‘working’ perfusion apparatus described by Hewett et al. [18]. The perfusion was established with a modified oxygenated Krebs–Henseleit buffer with the following concentrations (in mM): 118.4 NaCl, 4.1 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 1.17 KH2PO4, 1.46 MgCl2 and 11.1 glucose. The perfusion buffer was previously saturated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.4 at 37°C. To prevent the myocardium from drying out, the heart chamber, in which hearts were suspended, was covered and the humidity was kept at a constant level (90–95%). In all experiments global ischemia was induced for 20 min. followed by 2 hrs of reperfusion. In additional experiments, mice were i.p. injected with 50 μmol/kg of tin protoporphyrin IX (SnPPIX), an HO enzyme inhibitor, 1 day prior to the isolation of the heart and induction of ischemia and reperfusion. HO enzyme activities and recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function were measured in hearts obtained from NTg, HO-1 Tg and HO-1 Tg-SnPPIX treated mice. The schematic presentation of the experimental time course and parameters measured are shown in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Schematic presentation of the experimental time course.

Registration of VF and measurement of cardiac function

Epicardial electrocardiograms (ECGs) were recorded throughout the experimental period by two silver electrodes attached directly to the heart and connected to a data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Powerlab, Castle Hill, Australia). ECGs were analysed to determine the presence or absence of VF. Hearts were considered to be in VF if an irregular undulating baseline was apparent on ECGs. If the duration of VF was longer than 2 min., the VF was defined as sustained VF, otherwise, the VF was non-sustained. If VF developed and the sinus rhythm did not spontaneously return within the first 2 min. of reperfusion, hearts were electrically defibrillated by a defibrillator using two silver electrodes and 15 V square-wave pulse of 1 msec. duration and reperfused. AF and CF rates were measured by a timed collection of the aortic and coronary effluents that dripped from the heart. Before ischemia and during reperfusion, heart rate (HR), CF and AF were registered. AOP and AOPdp/dt were measured by a computer acquisition system (ADInstruments).

Measurement of infarct size

Infarct size was measured, at the end of each experiment, with 10 ml of 1% triphenyl tetrazolium solution in phosphate buffer (Na2HPO4 88 mM, NaH2PO4 1.8 mM) injected via the side arm of the aortic cannula then stored at −70°C for later analysis. Frozen hearts were sliced transversely [19] in a plane perpendicular to the apico-basal axis into 1–2-mm-thick sections, weighted, blotted dry, placed in between microscope slides and scanned on a Hewlett-Packard Scanjet 5p single pass flat bed scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Using the NIH Image 1.61 image processing software, each digitized image was subjected to equivalent degrees of background subtraction, brightness and contrast enhancement for improved clarity and distinctness. Infarct zones of each slice were traced and the respective areas were calculated in terms of pixels [20]. The areas were measured by computerized planimetry software and these areas were multiplied by the weight of each slice, then the results summed up to obtain the weight of the risk zone (total weight of the left ventricle [LV], mg) and the infarct zone (mg). Infarct size was expressed as the ratio, in percent, of the infarct zone to the risk zone.

Northern blots and RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from the LVs and right ventricles (RVs), and septum (S; about 50 mg) by guanidine isothiocyanate acid/phenol method [21], and 5 μg total RNA was used to synthesize first strand cDNA by the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). The product of cDNA was amplified by PCR with specific primers for rat HO-1 exon 5 (CCC-TTC-CTG-TGT-CTT-CCT-TTG and ACA-GCC-GCC-TCT-ACC-GAC-CAC-A). The product of RT-PCR was separated using 1.5% agarose gel, and visualized by ethidium bromide.

Western blots

Myocardial samples from LV, RV and S were homogenized in Tris-HCl (13.2 mM/l), glycerol (5.5%), SDS (0.44%) and β-mercaptoethanol. The same amount of soluble protein (50 μg) was fractionated by Tris-glycine-SDS-PAGE (12%) electrophoresis, and Western blot was carried out as described by Pellacani et al. [22] with the use of an antibody for recombinant rat HO-1 protein.

Measurement of HO activity

Fifty milligrams of tissue were homogenized in 10 ml of 200 mM phosphate buffer, and then centrifuged at 19,000 × g 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and recentrifuged at 100,000 × g 4°C for 60 min., and precipitated fractions were suspended in 2 ml of 100 mM K-phosphate buffer. Biliverdin reductase was crudely purified as described by Tenhunen et al. [23], and HO activity was assayed as described by Yoshida et al. [24]. Reaction mixtures consisted of (final volume 2 ml) 100 μM K-phosphate (pH 7.4), 15 nM hemin, 300 μM bovine serum albumin, 1 mg biliverdin reductase and 1 mg microsomal fraction of cardiac tissue. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 hr at 37°C in dark in a shaking water bath and was stopped by placing the test on ice. Incubation mixtures were then scanned using a scanning spectrophotometer, and the amount of bilirubin was calculated as the difference between absorbance at 464 and 530 nm [25]. Proteins were determined by the method of Lowry et al. [26], in microsomal fractions.

Measurement of CO

Tissue CO content using gas chromatography was detected as described by Cook et al. [27]. Briefly, hearts were homogenized in 4 volumes of 0.1 M phosphate-buffer (pH: 7.4) using an ×520 homogenizer (Ingenieurburo CAT, M. Zipperer GmbH, Staufen, Germany). The homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min. at 12,800 × g and the supernatant fractions were used for the determination of tissue CO content. The reaction mixtures contain: 150 μl of supernatant, 60 μl of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) (4.5 mM) and 50 μl of 3.5/0.35 mM methemalbumin, and for blank samples 60 μl phosphate buffer was used instead of NADPH. Samples were pre-incubated at 37°C for 5 min., then the headspace was purged and the incubation was continued for 1 hr in dark at 37°C. The reaction stopped by placing the samples on ice and the headspace gas was analysed. One thousand microlitres of the headspace gas from each vial was injected into the gas chromatograph using a gastight syringe (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV, USA) in hydrogen gas flow with a speed of 30 ml/min.. Analysis took place during the next 150 sec. on a 200 cm stainless-steel column with a 0.3 cm inner diameter. The detector was a thermal conductivity detector with an AC current of 80 mA. The individual value was expressed in millivolts. The column was packed with Molselect 5 Å and maintained at 30°C. The temperature of the injector and detector was controlled and kept at 50°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (7 μm) of tissue were incubated in the presence of polyclonal antibody and purified liver HO-1 obtained from rats (Stress Gen Biotech., Victoria, BC, Canada). Reactions were visualized by immunoperoxidase colour reaction in NTg, HO-1 Tg and HO-1 KO ischemic/reperfused mouse myocardium. Formalin fixed tissues were paraffin embedded and 7 μm sections were placed on poly-l-lysine coated glass slides (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following deparaffinization and rehydration, samples were used for quenching endogenous peroxidases and blocking non-specific binding sites by 3% H2O2 in normal goat serum. Sections were incubated for another 2 hrs with HO-1 antibody at a dilution of 1:750 as described in the manufacturer’s manual. After 10 min. of phosphate-buffered solution washing, slides were incubated for additional 30 min. in the presence of purified biotinylated anti/rabbit IgG (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:200. Slides were rewashed in phosphate-buffered solution and incubated with peroxidase conjugated streptavidin (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) for 30 min. followed by red colour development using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole in 0.1 M of acetate buffer (pH 5.2). Sections were counter-stained with Gill’s haematoxylin for 15–20 sec., rinsed with deionized water and dipped in 1% of lithium carbonate. After draining off water, slides were placed in oven for 30 min. at 80°C, and then covered with permount cover slips. Sections were photographed using a Zeiss (Göttingen, Germany) light microscope.

Measurement of cellular Na+, K+ and Ca2+

Cellular cations were measured as previously described [28]. In brief, hearts were rapidly cooled to 0–5°C by submersion in, and then perfused for 5 min. with an ice-cold ion-free buffer solution containing 100 mmol/l of trishydroxy-methyl-amino-methane and 220 mmol/l of sucrose to wash out ions from the extracellular space and to stop enzyme activities responsible for membrane ion transport processes. Five minutes of cold washing of the heart washed out >90% of the ions from the extracellular space [29]. Following the wash out period, left ventricular tissues were dried for 48 hrs at 100°C, and made ash at 550°C for 20 hrs. The ash was dissolved in 5 ml of 3 M nitric acid and diluted 10-fold with ion-free deionized water. Cellular Na+ was measured at a wavelength of 330.3 nm, K+ was measured at 404.4 nm, and Ca2+ at 422.7 nm in air-acetylene flame using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer 1100-B, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). This method for the measurement of cellular ion contents has been previously described in the myocardium [29, 30] and central nervous system [31].

Statistics

The data for HR, CF, AF, AOP, AOPdp/dt, cellular Na+, K+, Ca 2+ and infarct size were expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. ANOVA was first carried out to test for any differences between the mean values of groups. If differences were established the values of NTg group were compared to those of HO-1 Tg, and HO-1 KO−/− groups by multiple t-test followed by Bonferroni test. Because of the non-parametric distribution of the incidence of VF (sustained and non-sustained), the chi-square test was used to compare individual groups. A change of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

For the confirmation of rat HO-1 expression at mRNA level, RT-PCR was used and total RNA was isolated from the non-ischemic LVs and RVs, and S of Tg and NTg littermates. The PCR product was rat HO-1 specific and was detected selectively in Tg mouse samples by RT-PCR (Fig. 2A) and Western blot (Fig. 2B). Under our experimental conditions, two clones were identified, and the fragment, the promoter and HO-1 gene were excised by SfiI. Primers were amplified using 166 bp product originated from rat HO-1 exon 5. To avoid genomic DNA-based amplification, before the first stand cDNA synthesis, all biopsies were treated with DNase. The specific band was amplified in tissues obtained from LV, RV and S, respectively, by PCR from RNA samples of Tg mouse from different lines (Fig. 2A, Tg1: upper part, Tg2: middle part), but was absent in RNA samples of NTg (Fig. 2A, lower part). Tg1 and Tg2 proteins were also detected by Western blots in the LV, RV and S of mouse hearts (Fig. 2B, upper and middle parts), but the expression of rat HO-1 proteins were absent in the NTg mouse myocardium (Fig. 2B, lower part).

Fig 2.

The detection of rat HO-1 transgene by PCR (A) and Western blot (B) and HO enzyme activities (C) in mouse hearts. Total RNA obtained from mouse LV, RV and S, respectively, was used to synthesize first strand cDNA. HO-1 originated from rat was amplified by PCR exon 5-specific primer and visualized with ethidium bromide as a 166-bp band by agarose gel electrophoresis. In two clones, the specific band was amplified from RNA samples of RV, LV and S, respectively, in transgene (transgene 1 and transgene 2) mice (A, upper and middle parts), but it was absent in the RNA sample of NTg littermate (A, lower part). Western blots (B) also depict the expression of rat transgene 1, transgene 2 and NTg in the LV, RV and S of mouse hearts. HO enzyme activities are also shown in the LV, RV and S in NTg and Tg myocardium (C). n = 6 in each group, mean ± S.E.M., *P < 0.05, comparisons were made to the NTg values in each group.

HO enzyme activities were also measured in the LV, RV and S obtained from NTg and Tg mice (Fig. 2C). The results show that HO activities were significantly increased in samples obtained from the LV, RV and S of Tg mouse hearts in comparison with NTg values (Fig. 2C) indicating the function of Tg1 and Tg2 genes in the mouse myocardium. It is important to note that HO-1 mRNA and protein were not detected in NTg mouse myocardium either by PCR (Fig. 2A, lower part) or Western blot (Fig. 2B, lower part), but HO enzyme activities were present in the samples of NTg mouse myocardium including LV, RV and S, respectively, indicating that measured HO enzyme activity involves all isoforms such as HO-1, HO-2, HO-3 and HO-4 (Fig. 2C). Thus, the differences in HO enzyme activities (Fig. 2C) between NTg and Tg in the LV, RV and S were clearly related to the rat HO-1 transgene in the mouse myocardium.

Table 1 shows the recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function in NTg and HO-1 Tg hearts subjected to 20 min. of normothermic global ischemia followed by 2 hrs of reperfusion. Before the induction of ischemia significant changes were not detected between NTg and HO-1 Tg groups in HR, CF, AF, AOP and AOPdp/dt. Upon reperfusion, the post-ischemic recovery of CF, AF, AOP and AOPdp/dt were observed in the HO-1 Tg group in comparison with the NTg values without any significant differences in HR. Thus, for instance, after 30 and 120 min. of reperfusion, AF was significantly increased from its NTg control values of 0.9 ± 0.1 ml/min. and 0.8 ± 0.1 ml/min. to 2.3 ± 0.2 ml/min. (P < 0.05) and 2.2 ± 0.2 ml/min. (P < 0.05) in the Tg group, respectively (Table 1). The same pattern was observed in the post-ischemic recovery in CF, AOP and AOPdp/dt (Table 1). The results also show (Table 1) that 50 μmol/kg of SnPPIX, an HO enzyme inhibitor, abolished the post-ischemic recovery of cardiac function in comparison with the observed protection in the HO-1 Tg group. Thus, the values obtained in the HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX group were not statistically significant in comparison with the NTg values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of 20 min. of ischemia followed by 30 and 120 min. of reperfusion on the recovery of cardiac function in NTg and HO-1 Tg, and the effect of SnPPIX

| Before ischemia | After reperfusion (RE) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min. | 120 min. | ||||||||||||||

| HR | CF | AF | AOP | AOPdp/dt | HR | CF | AF | AOP | AOPdp/dt | HR | CF | AF | AOP | AOPdp/dt | |

| NTg | 288 ± 9 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 157 ± 7 | 3794 ± 73 | 255 ± 9 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 72 ± 6 | 945 ± 44 | 262 ± 9 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 67 ± 4 | 930 ± 51 |

| HO-1 Tg | 292 ± 8 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 149 ± 6 | 3834 ± 85 | 261 ± 7 | 2.8 ± 0.1* | 2.3 ± 0.2* | 95 ± 7* | 2000 ± 63* | 269 ± 8 | 2.9 ± 0.2* | 2.2 ± 0.2* | 91 ± 6* | 1880 ± 80* |

| HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX | 294 ± 9 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 152 ± 9 | 3815 ± 94 | 265 ± 8 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 78 ± 7 | 1018 ± 80 | 270 ± 9 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 72 ± 8 | 1000 ± 77 |

n = 6 in each group, mean ± S.E.M.; HR: heart rate, beats/min.; CF: coronary flow, ml/min.; AF: aortic flow, ml/min.; AOP: aortic pressure, mmHg; AOPdp/dt: first derivative of aortic pressure, mmHg/sec.; SnPPIX: tin protoporphyrin IX. *P < 0.05, comparisons were made to the time-matched NTg values.

Figure 3 depicts representative curves of endogenous CO production detected by GC in NTg, Tg and Tg SnPPIX treated myocardium subjected to 20 min. ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion. It is shown that in HO-1 Tg hearts subjected to 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion (Fig. 3B, chromatogram), a substantial increase in CO production was observed in comparison with the NTg myocardium (Fig. 3A, chromatogram). However, the endogenous production of CO in the HO-1 Tg myocardium treated with SnPPIX was detected at relatively low level. (Fig. 3C, chromatogram).

Fig 3.

Representative GC chromatograms for the demonstration of endogenous CO production in NTg [chromatogram (a)], HO-1 Tg [chromatogram (b)] and HO-1 Tg mouse myocardium treated with SnPPIX [HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX, chromatogram (c)]. Hearts were subjected to 20 min. of normothermic global ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion. The results show, in NTg myocardium [chromatogram (a)], that there is a well-detectable endogenous CO production after 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion. The endogenous CO production was substantially increased in HO-1 Tg myocardium (chromatogram (b)], and a reduction of endogenous CO production was recorded in HO-1 myocardium treated with SnPPIX [chromatogram (c)].

Figure 4 shows representative pictures of infarct size (Fig. 4A, lower part, to the right) and immunohistochemical staining of HO-1 (Fig. 4A, lower part to the left) in isolated mouse hearts subjected to ischemia and reperfusion. The infarct size (Fig. 4A) was markedly reduced from its NTg control value of 37 ± 4% to 20 ± 6% (*P < 0.05) in the HO-1 Tg group (Fig. 4A). However, in the HO-1 KO hearts, the infarct size was significantly increased to 47 ± 5% (*P < 0.05) in comparison with NTg group (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Infarct size and HO-1 staining in isolated NTg, Tg and HO-1 KO mouse hearts subjected to 20 min. of normotermic global ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion. *P < 0.05 compared to the NTg control values. n = 6 in each group. Infarct is represented by white area surrounding by the living red tissues [(A), to the right lower part]. Immunochemical localization of HO-1 is stained by blue in NTg, Tg and KO myocardium [(A), to the left lower part]. (B) shows the incidence (%) of total (open bars) and sustained (hatched bars) reperfusion-induced VF in isolated NTg, Tg and KO mouse hearts. The incidence of reperfusion-induced VF was registered, and comparisons were made to the values of NTg group. n = 12 in each group, *P < 0.05. Because of the non-parametric distribution in the incidence of total and sustained VF, the chi-square non-parametric test was used to compare individual groups. This figure and data were presented at the FEAM Meeting held in Bucharest, Romania, in March, 2010, and published in the current issue of the JCMM, 2011, by Bak et al.

In addition, Figure 4A shows the representative immunohistochemical localization of HO-1 (Fig. 4A, lower part – to the left) in NTg, Tg and HO-1 KO ischemic/reperfused mouse hearts. Left ventricular cardiac samples were obtained from NTg, HO-1 Tg and HO-1 KO mouse myocardium, respectively. Cytoplasmic protein staining (blue) of HO-1 in NTg myocardium was detected (Fig. 4A, lower part – to the left) which was more intense in Tg myocardium, and markedly reduced in KO myocardium after 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion (Fig. 4A, lower part – to the left).

Figure 4 also shows the incidence (%) of reperfusion-induced VF (Fig. 4B) as total (sustained and non-sustained) and sustained VF in NTg, Tg and KO mouse groups. The incidence of reperfusion-induced total and sustained VF (Fig. 4B) was significantly reduced from their NTg control values of 92% and 83% to 25% (*P < 0.05) and 8% (*P < 0.05), respectively, in the HO-1 Tg group. In the KO group (Fig. 4B), the incidence of reperfusion-induced total and sustained VF were 100% and 100%, respectively, showing the important role of HO-1 in arrhythmogenesis.

Table 2 clearly shows that left ventricular tissue Na+, K+ and Ca2+ contents were not significantly varied between NTg, HO-1 Tg and HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX groups before the induction of ischemia. However, the results (Table 2) also depict that left ventricular tissue Na+ and Ca2+ contents were significantly reduced after 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion in the HO-1 Tg group in comparison with the NTg and HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX values. In addition, the left ventricular tissue K+ content (Table 2) was significantly elevated (261 ± 8 μmol/g dry weight, P < 0.05) in the HO-1 Tg group compared to the K+ loss measured in the NTg group (229 ± 5 μmol/g dry weight).

Table 2.

Cellular Na+, K+ and Ca2+ contents (μmol/g dry weight) in the left ventricular tissue before ischemia and after 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion in NTg and HO-1 Tg, and the effect of SnPPIX

| Group | Before ischemia | After 20 min. ischemia followed by 120 min. reperfusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | |

| NTg | 31 ± 3 | 282 ± 6 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 84 ± 5 | 229 ± 5 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| HO-1 Tg | 27 ± 4 | 277 ± 7 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 58 ± 7* | 261 ± 8* | 2.5 ± 0.5* |

| HO-1 Tg + SnPPIX | 35 ± 5 | 286 ± 9 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 90 ± 9 | 219 ± 9 | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

n = 6 in each group, mean ± S.E.M., *P< 0.05, comparisons were made to the time-matched NTg values; SnPPIX: tin protoporphyrin IX.

In hearts treated with SnPPIX, the ischemia/reperfusion resulted in the same maldistribution in cellular Na+, K+ and Ca2+ contents to those of the NTg group (Table 2). In other worlds, SnPPIX completely abolished the cardiac protection detected concerning the cellular Na+ and Ca2+ gains, and K+ loss in the HO-1 Tg group in the ischemic/reperfused myocardium. The values measured in the SnPPIX group were the same to the NTg mouse hearts (Table 2) after 20 min. of ischemia followed by 120 min. of reperfusion.

Discussion

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the industrialized society, and considerable efforts have been made to target interventional therapies for this condition. In recent years, the concept of the modification in various gene expressions or repressions has emerged as new mechanisms and therapeutic tools for the induction of protection in ischemic/reperfused tissues. It is now also relatively well accepted that many human vascular diseases such as hypertension [32, 33], heart failure [34–36], organ transplantation [9, 37] and arrhythmias [38, 39] can be treated with various interventions at a level of underlying genetic mechanisms. Several approaches have been made to manipulate cell phenotypes including the inhibition of genes associated with cell proliferation by preventing the development of atherosclerosis and restenosis [40–42] and the production of growth factors to promote angiogenesis [43–47] for the treatment of peripheral vascular disease and myocardial ischemia.

In our previous studies, we found a substantial reduction in the expression of HO-1 mRNA and its protein with a causative reduction in the HO-1 enzyme activity in fibrillated ischemic/reperfused rat myocardium [13]. Moreover, we have shown that, in this respect, no difference exists between non-diabetic and diabetic heart [48]. Furthermore, HO-1 KO mouse hearts displayed a reduced left ventricular function after ischemia/reperfusion [14]. If HO-1 system has a crucial role in the protection against ischemic/reperfusion-induced injury in the myocardium, with the enhanced expression of the HO-1, more ischemic tissue can be salvaged. Therefore, in the present study, because the HO-1 system can play a crucial role in the pathology of the ischemic/reperfused myocardium, we decided to approach the question from a different angle using HO-1 Tg mouse hearts.

We generated HO-1 overexpressing Tg mice with an elevation in baseline HO enzyme activity by about 50% in the LV, RV and S, respectively. Thus, the application of a genome-based transgene resulted in expression levels in relation with increased HO enzyme activities in comparison with those of HO activities levels detected in the LV, RV and S obtained from NTg mice. Although, in our studies, the very similar homology between the mouse and rat HO-1 made it impossible to differentiate the HO-1 and Tg-induced enzyme activities, but we were able to distinguish them at mRNA level. In addition, our results obtained in NTg, HO-1 Tg and Tg-SnPPIX treated mouse hearts, we favour the idea that increased endogenous CO production levels in the myocardium represents the major signal transduction responsible for HO-1 related protection reflected in the improvement of the recovery in post-ischemic cardiac function, reduction of the incidence of reperfusion-induced VF and infarct size connected to the recovery of cellular ion contents. Our results further supported by the complete loss of cardiac protection in the Tg ischemic/reperfused mice treated with SnPPIX, the inhibitor of HO enzyme.

The exact mechanism by which HO-1 induces cardiac protection remains to be elucidated; however, one of the most significant protective mechanisms of the HO system can be explained by the generation of endogenous CO and its signalling mechanism. CO could suppress cell apoptosis [37] suggesting that the anti-apoptotic effect of HO-1 is mediated via the generation of CO. In addition, anti-inflammatory property of CO suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory genes associated with the activation of monocyte/MΦ [49].

Another possible cellular signalling mechanism of CO is associated with the guanylyl cyclase activation and tissue levels of guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in isolated ischemic/reperfused myocardium [50]. Very low concentrations of CO, in the perfusion buffer, afford a significant protection against the ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage in isolated buffer perfused hearts. The isolated buffer perfused heart could be an ideal model to study the direct effect of exogenous CO on cardiac function and molecular signalling because the blood and its elements are excluded from the model, thus the oxygen transport to cells and tissues is not directly damaged via the CO/blood/haemoglobin system. Previous results have shown that low concentrations of exogenous CO protect the isolated ischemic/reperfused myocardium and act by increasing tissue cAMP and cGMP levels [50]. Indeed, a moderate increase in cAMP content could lead to arrhythmogenesis and development of various arrhythmias by elevating cytosolic calcium levels [51] in the ischemic and post-ischemic myocardium. It is of interest to note that multiple increases in cGMP levels could mask and interfere with the arrhythmogenic effects of cAMP leading to the suppression of reperfusion-induced VF in the myocardium [50]. The significant increase in cGMP levels can be related to guanylate cyclase activities in CO-treated myocardium, and suggests that induction of guanylate cyclase-cGMP system via CO signalling is essential for cardioprotection in ischemic/reperfused hearts. However, not only the absolute levels of cGMP and cAMP but also the ratio of these two nucleotides are critical factors that determine the recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function after ischemia and reperfusion [52]. Thus, the lower the cAMP/cGMP ratio is during ischemia, the better is the post-ischemic cardiac recovery achieved in isolated ischemic/reperfused hearts.

It has to be noted that Lakkisto et al. have recently found that cadioprotection induced by hemin, a well-known inducer of haemoxigenase 1, is independent of cGMP levels and, at least in part, being mediated via the preservation of C×43 [53]. They found that elevated HO-1 levels, induced by hemin, are not accompanied by elevated cGMP levels. In our previous study [50], we have found that cGMP levels are elevated after exogenous CO application; moreover, after exogenous CO administration the ratio of cAMP/cGMP is reduced. In their study [53], the authors measured only the level of cGMP and not the ratio of cAMP/cGMP. The difference between their and our results is probably due to the higher CO concentration after the exogenous administration.

Although not specifically studied in the present investigation at molecular level, it is of interest to note the findings of Piantadosi et al. [54] with myocardial cells. In their studies, Piantadosi et al. implicated the role of HO-1/CO pathway in mitochondrial biogenesis through Akt1 activation [55] involving nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf)2 expression, downstream GSK-3β blockade and Nrf2 nuclear translocation leading to Nrf2-dependent activation of nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1 transcription. Their finding suggest HO-1/CO, by sequentially activating the aforementioned two transcription factors, as a remarkable component of a prosurvival program of mitochondrial biogenesis connected to cellular antioxidant defence mechanisms [56, 57].

Today, when so many advances and efforts are being made in molecular biology and genetics, we tend to lose sight of the importance of basic ions such as Na+, K+ and Ca2+ in both clinical and experimental studies. As a gap, in changes between various gene expression and/or repression and the function of myocardial tissue, could closely be connected with changes in myocardial tissue ion contents. An important finding such a final endpoint of our present study was the myocardial K+– conserving effect’ related to the prevention of cellular Na+ and Ca2+ gains in Tg myocardium, and this cardiac protection can be reversed by SnPPIX, an HO-1 inhibitor. HO-1–bilirubin system and one of its by-products, CO, are essential for regulation of cardiac function and ion transport across cell membranes via the stabilization of various Na, K and Ca ion channels possibly by an effect exerted on Na-K-ATPase, and these transient outward and inward currents are thought to underline the delayed after depolarization that can be observed after the action potential in Ca-loaded cardiac tissue propagating rhythm disturbances [58]. There are significant differences in the cellular signalling mechanisms induced by CO when they are compared with the actions of other interventions that elevate cyclic nucleotides in tissues. CO has been proposed to increase KCa channel Ca2+ sensitivity in arterial smooth muscle cells [59], and the data of Perez et al. [60] suggest that CO increases Ca2+ spark coupling by shifting the Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa channels produced by Ca2+ sparks. Thus, CO may act upon KCa channel β subunits to enhance the coupling relationship leading to cellular K+ loss, and Ca2+ and Na+ gains as we observed in our present studies.

In our study we have shown that CO level was significantly increased in the HO-1 Tg mouse myocardium. However, we did not measure CO levels during reperfusion; therefore, we believe that the elevated CO production can be responsible for the protection during reperfusion in Tg myocardium. Besides this, we cannot rule out the contribution of other HO-1 related molecules such as biliverdin and bilirubin in the observed cardiac protection.

In conclusion, using HO-1 Tg, we have demonstrated the direct causative role of HO-1 in protection against ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury. Specifically, our results show a significant recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function, prevention of the development of reperfusion-induced VF and reduction in infarct size. In addition, we have provided new insights into the ionic mechanisms by which HO-1 may contribute to the attenuation of reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in HO-1 Tg. We believe that these studies would help in developing novel therapies based on targeting HO-1 for the treatment of ischemia/reperfusion injury in patients with coronary artery disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from OTKA (K-72315, OTKA 78223), TAMOP 4.2.2–08/1–2008-0007 and TAMOP 4.2.1.B-2010.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1: redox regulation of a stress protein in lung and cell culture models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:80–91. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee PJ, Jiang BH, Chin BY, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5375–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otterbein LE, Lee PJ, Chin BY, et al. Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest. 1999;116:61S–3S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.61s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve VE, Tyrrell RM. Heme oxygenase induction mediates the photoimmunoprotective activity of UVA radiation in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9317–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yet SF, Tian R, Layne MD, et al. Cardiac-specific expression of heme oxygenase-1 protects against ischemia and reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:168–73. doi: 10.1161/hh1401.093314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi AM, Alam J. Heme oxygenase-1: function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:9–19. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minamino T, Christou H, Hsieh CM, et al. Targeted expression of heme oxygenase-1 prevents the pulmonary inflammatory and vascular responses to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8798–803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161272598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araujo JA, Meng L, Tward AD, et al. Systemic rather than local heme oxygenase-1 overexpression improves cardiac allograft outcomes in a new transgenic mouse. J Immunol. 2003;171:1572–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawle P, Foresti R, Mann BE, et al. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules (CO-RMs) attenuate the inflammatory response elicited by lipopolysaccharide in RAW264.7 murine macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:800–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Wei J, Peng DH, et al. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2005;54:778–84. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang YL, Tang Y, Zhang YC, et al. Improved graft mesenchymal stem cell survival in ischemic heart with a hypoxia-regulated heme oxygenase-1 vector. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1339–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bak I, Papp G, Turoczi T, et al. The role of heme oxygenase-related carbon monoxide and ventricular fibrillation in ischemic/ reperfused hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:639–48. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bak I, Szendrei L, Turoczi T, et al. Heme oxygenase-1-related carbon monoxide production and ventricular fibrillation in isolated ischemic/reperfused mouse myocardium. FASEB J. 2003;17:2133–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0032fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong K, Piper DR, Diaz-Valdecantos A, et al. De novo KCNQ1 mutation responsible for atrial fibrillation and short QT syndrome in utero. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, et al. Ca(V)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8089–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewett TE, Grupp IL, Grupp G, et al. Alpha-skeletal actin is associated with increased contractility in the mouse heart. Circ Res. 1994;74:740–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz JE, Yao Z, Cavero I, et al. Glibenclamide-induced blockade of ischemic preconditioning is time dependent in intact rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2607–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickson EW, Blehar DJ, Carraway RE, et al. Naloxone blocks transferred preconditioning in isolated rabbit hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1751–6. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pellacani A, Wiesel P, Sharma A, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 during endotoxemia is downregulated by transforming growth factor-beta1. Circ Res. 1998;83:396–403. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenhunen R, Ross ME, Marver HS, et al. Reduced nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate dependent biliverdin reductase: partial purification and characterization. Biochemistry. 1970;9:298–303. doi: 10.1021/bi00804a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida T, Takahashi S, Kikuchi G. Partial purification and reconstitution of the heme oxygenase system from pig spleen microsomes. J Biochem. 1974;75:1187–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita T, Perrella MA, Lee ME, et al. Smooth muscle cell-derived carbon monoxide is a regulator of vascular cGMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1475–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, et al. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook MN, Nakatsu K, Marks GS, et al. Heme oxygenase activity in the adult rat aorta and liver as measured by carbon monoxide formation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:515–8. doi: 10.1139/y95-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tosaki A, Balint S, Szekeres L. Protective effect of lidocaine against ischemia and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias and shifts of myocardial sodium, potassium, and calcium content. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;12:621–8. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pridjian AK, Levitsky S, Krukenkamp I, et al. Developmental changes in reperfusion injury. A comparison of intracellular cation accumulation in the newborn, neonatal, and adult heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;93:428–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alto LE, Dhalla NS. Myocardial cation contents during induction of calcium paradox. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:H713–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.237.6.H713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szabo ME, Gallyas E, Bak I, et al. Heme oxygenase-1-related carbon monoxide and flavonoids in ischemic/reperfused rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3727–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson DL, Dwinell MR, Greene AS, et al. Chromosome substitution reveals the genetic basis of Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F837–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90341.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai CT, Hwang JJ, Lai LP, et al. Interaction of gender, hypertension, and the angiotensinogen gene haplotypes on the risk of coronary artery disease in a large angiographic cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis J, Wen H, Edwards T, et al. Allele and species dependent contractile defects by restrictive and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-linked troponin I mutants. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monti J, Fischer J, Paskas S, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a susceptibility factor for heart failure in a rat model of human disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:529–37. doi: 10.1038/ng.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Hu A, Yuan H, et al. A missense mutation in the CHRM2 gene is associated with familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2008;102:1426–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato K, Balla J, Otterbein L, et al. Carbon monoxide generated by heme oxygenase-1 suppresses the rejection of mouse-to-rat cardiac transplants. J Immunol. 2001;166:4185–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groh WJ, Groh MR, Saha C, et al. Electrocardiographic abnormalities and sudden death in myotonic dystrophy type 1. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2688–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knollmann BC, Roden DM. A genetic framework for improving arrhythmia therapy. Nature. 2008;451:929–36. doi: 10.1038/nature06799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zahradka P, Wright B, Fuerst M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and gamma ligands differentially affect smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:651–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honda T, Kaikita K, Tsujita K, et al. Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice with metabolic disorders. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:915–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wayman NS, Hattori Y, McDonald MC, et al. Ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha) reduce myocardial infarct size. FASEB J. 2002;16:1027–40. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma S, Dewald O, Adrogue J, et al. Induction of antioxidant gene expression in a mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy is dependent on reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:2223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arab S, Konstantinov IE, Boscarino C, et al. Early gene expression profiles during intraoperative myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Simpson JA, Brunt KR, et al. Preemptive heme oxygenase-1 gene delivery reveals reduced mortality and preservation of left ventricular function 1 yr after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H48–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00741.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, et al. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:720–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Zhan L, et al. Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside induces neovascularization-mediated cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in hypercholesterolemic myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Csonka C, Varga E, Kovacs P, et al. Heme oxygenase and cardiac function in ischemic/reperfused rat hearts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Alam J, et al. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:422–8. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bak I, Varadi J, Nagy N, et al. The role of exogenous carbon monoxide in the recovery of post-ischemic cardiac function in buffer perfused isolated rat hearts. Cell Mol Biol. 2005;51:453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.du Toit EF, Opie LH. Modulation of severity of reperfusion stunning in the isolated rat heart by agents altering calcium flux at onset of reperfusion. Circ Res. 1992;70:960–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.5.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du Toit EF, Meiring J, Opie LH. Relation of cyclic nucleotide ratios to ischemic and reperfusion injury in nitric oxide-donor treated rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:529–38. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakkisto P, Csonka C, Fodor G, et al. The heme oxygenase inducer hemin protects against cardiac dysfunction and ventricular fibrillation in ischaemic/reperfused rat hearts: role of connexin 43. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2009;69:209–18. doi: 10.1080/00365510802474392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piantadosi CA, Carraway MS, Babiker A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ Res. 2008;103:1232–40. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000338597.71702.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Tatro LG, et al. A new activating role for CO in cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:299–308. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagener FA, Volk HD, Willis D, et al. Different faces of the heme-heme oxygenase system in inflammation. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:551–71. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: update 2005. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1761–6. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kass RS, Lederer WJ, Tsien RW, et al. Role of calcium ions in transient inward currents and aftercontractions induced by strophanthidin in cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1978;281:187–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang R, Wu L, Wang Z. The direct effect of carbon monoxide on KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:285–91. doi: 10.1007/s004240050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Micromolar Ca(2+) from sparks activates Ca(2+)-sensitive K(+) channels in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1769–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]