Abstract

Summary

Competition between microbial species is a product of, yet can lead to a reduction in, the microbial diversity of specific habitats. Microbial habitats can resemble ecological battlefields where microbial cells struggle to dominate and/or annihilate each other and we explore the hypothesis that (like plant weeds) some microbes are genetically hard-wired to behave in a vigorous and ecologically aggressive manner. These ‘microbial weeds’ are able to dominate the communities that develop in fertile but uncolonized – or at least partially vacant – habitats via traits enabling them to out-grow competitors; robust tolerances to habitat-relevant stress parameters and highly efficient energy-generation systems; avoidance of or resistance to viral infection, predation and grazers; potent antimicrobial systems; and exceptional abilities to sequester and store resources. In addition, those associated with nutritionally complex habitats are extraordinarily versatile in their utilization of diverse substrates. Weed species typically deploy multiple types of antimicrobial including toxins; volatile organic compounds that act as either hydrophobic or highly chaotropic stressors; biosurfactants; organic acids; and moderately chaotropic solutes that are produced in bulk quantities (e.g. acetone, ethanol). Whereas ability to dominate communities is habitat-specific we suggest that some microbial species are archetypal weeds including generalists such as: Pichia anomala, Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas putida; specialists such as Dunaliella salina, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Lactobacillus spp. and other lactic acid bacteria; freshwater autotrophs Gonyostomum semen and Microcystis aeruginosa; obligate anaerobes such as Clostridium acetobutylicum; facultative pathogens such as Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Pantoea ananatis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; and other extremotolerant and extremophilic microbes such as Aspergillus spp., Salinibacter ruber and Haloquadratum walsbyi. Some microbes, such as Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium smegmatis and Pseudoxylaria spp., exhibit characteristics of both weed and non-weed species. We propose that the concept of nonweeds represents a ‘dustbin’ group that includes species such as Synodropsis spp., Polypaecilum pisce, Metschnikowia orientalis, Salmonella spp., and Caulobacter crescentus. We show that microbial weeds are conceptually distinct from plant weeds, microbial copiotrophs, r-strategists, and other ecophysiological groups of microorganism. Microbial weed species are unlikely to emerge from stationary-phase or other types of closed communities; it is open habitats that select for weed phenotypes. Specific characteristics that are common to diverse types of open habitat are identified, and implications of weed biology and open-habitat ecology are discussed in the context of further studies needed in the fields of environmental and applied microbiology.

Introduction

As the collective metabolism and ecological activities of microorganisms determine the health and sustainability of life on Earth it is essential to understand the function of both individual microbes and in their communities. The cellular systems of an insignificant portion of microbial species have been intensively characterized at the levels of biochemistry, cell biology, genomics and systems biology; and a substantial body of (top-down) studies has been published in the field of microbial ecology in relation to species interactions, community succession and environmental metagenomics. There are, however, some fundamental questions that remain unanswered in relation to the behaviour of microbial species within communities: what type of biology, for instance, enables microbes to dominate entire communities and their habitats and thereby determine levels of biodiversity in specific environments?

Plant species that primarily inhabit freshly disturbed habitats – known as weeds – are characterized by vigorous growth; tolerance to multiple stresses; exceptional reproduction, dispersal and survival mechanisms; a lack of specific environmental requirements; production of phytotoxic chemicals; and/or other competitive strategies (Table 1). The biology of plant weeds, including their phenotypic and genetic traits, has been the subject of extensive study over the past 100 years and is now relatively well characterized (Table 1; Long, 1932; Anderson, 1952; Salisbury, 1961; Hill, 1977; Mack et al., 2000; Schnitzler and Bailey, 2008; Bakker et al., 2009; Chou, 2010; Wu et al., 2011; Liberman et al., 2012). We hypothesize that weed biology is also pertinent to microbial species, but that the defining characteristic of microbial weeds is their ability to dominate their respective communities. In the field of plant ecology it is open habitats (such as freshly exposed fertile soil) that facilitate the emergence of weed species both within specific ecosystems and across evolutionary timescales. We propose that weed behaviour is equally prevalent in some microbial habitats, that open microbial habitats promote the emergence of microbial weed species, and that microbial weed biology represents a potent ecological and evolutionary mechanism of change for some microbial species and their communities.

Table 1.

A comparison of plant weeds and microbial weeds.a

| Plant weeds | Microbial weeds | References (plants/microbes) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Plant species that primarily grow in open (plant) habitatsb | Microbial species able to dominate communities that develop in open (microbial) habitatsc | Baker, 1965; Hill, 1977/current article; Cordero et al., 2012 |

| Ability to rapidly occupy available space | Important trait | Essential trait | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Overall vigourd and competitive ability | Typically vigorous; competitive ability usually superior to that of crop plants | Exceptional vigour and competitive ability | Hill, 1977/Figs 1 and 2; Tables S1 and 2–5 |

| Primary competitors | Intra-specific competition can be stronger than inter-specific competition | Intra-and inter-specific competition are likely to be stronger if dominance results from efficient resource acquisition or antimicrobial substances respectively | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Resource acquisition and storage | Acquisition and/or storage of water, light, nutrients etc. typically excellent | Acquisition and/or storage of nutrients, water and/or light typically excellent | Hill, 1977; Oatham, 1997; Sadeghi et al., 2007/Table5 |

| Reproduction and dispersal | Exceptionale | May not differ from non-weed species | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Obligatory associations or interactions with other organisms | Uncommon/atypical | Uncommon/atypical | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Ubiquity | Many species are environmentally ubiquitous | Not necessarily widespread outside the habitat which they dominate | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Germination | No special requirements; high tolerance to diverse stresses (see below) | No special requirements; high tolerance to diverse stresses (see below) | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Longevity of dormant propagules | Exceptional | May not differ from non-weeds | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Able to regenerate from fragments | Yes, especially root fragments | Not relevant | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Maintenance of growth rate during nutrient limitation | Some species, e.g. black-grass (Alopecurus mysuroides) on low-potassium soils | Many (photosynthetic as well as some heterotrophic) species | Hill, 1977/Table5; Benning, 1998 |

| Capable of creating a zone-of-inhibition | Not known | Yes, in some instances | [Not known]/Fleming, 1929 |

| Secretion of toxic substances | Some species produce phytotoxic inhibitors (exuded from leaves, roots, and/or necromass) | All species produce antimicrobial toxins (secreted into the extracellular environment)f | Chou, 2010/Table6 |

| Production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that act as stressors | Some hydrophobic and highly chaotropic compounds act as phytotoxic stressors (e.g. β-caryophellene) | Many species produce a spectrum of VOCs that can inhibit metabolic activity at concentrations in the nanomolar or low millimolar rangef | Wang et al., 2010; Inderjit et al., 2011; Tsubo et al., 2012/Table6 |

| Secretion of biosurfactants that act as stressors | Not known | Some species produce biosurfactants; substances that can solubilize hydrophobic substrates and act as cellular stressorsf | [Not known]/Tables3 and e; Nitschke et al., 2011 |

| Bulk production, and secretion, of moderately chaotropic substances | Not known | Some species produce ethanol, butanol, acetone etc. that are potent cellular stressors at millimolar and molar concentrationsf | [Not known]/Table6 |

| Saprotrophic activity resulting in toxic/stressful breakdown products | Not known | Some species degrade macromolecules to release inhibitory catabolic products (e.g. chaotropic stressors such as phenol, catechol and vanilling) | [Not known]/Park et al., 2004; 2007; Zuroff and Curtis, 2012 |

| Acidification of habitat | Not known | Some species, via bulk production of organic acidsf | [Not known]/Table6 |

| Secretion of aggressive enzymes | Unlikely | Some speciesf | [Not known]/Table6; Walker, 2011 |

| Tolerance to environmental stressesh | Tolerant to multiple, habitat-relevant stress parameters | Tolerant to multiple, habitat-relevant stress parameters | Hill, 1977/Fig. 2, Tables2–4 and 6 |

| Resistance to toxins and/or stressors of biotic originh | Likely | Yes, most species | Hill, 1977/Fig. 2; Tables2–4 and 6 |

| Phenotypic plasticity and intra-specific variation | Greater than that of crop plants | Likely to be above average (e.g. in relation to stress biology) | Hill, 1977/current article; see references in Todd et al., 2004 |

| Resistance to viruses, predators, and/or grazers | Some species can tolerate, resist, and/or repel viruses, sucking insects and grazing animals; and may contain poisonous substances – or have morphological adaptations such as spines – that minimize losses through grazing | Some strains/species can tolerate, resist, repel and/or avoid viruses, grazing plankton and arthropods etc; may contain toxic metabolites or have behavioural adaptations – e.g. formation of large microcolonies – that minimize losses through grazing/predation; and may inhabit environments that are too extreme for predatory species | Thurston et al., 2001; Ralphs, 2002; Shukurov et al., 2012/Table6 |

| Karyotype | Commonly of hybrid origin, polyploid or aneuploid | Frequency of hybrid origin, polyploidy and aneuploidy not yet tested; may contain plasmids that contribute to weediness | Anderson, 1952/Tables3 and e |

| Proportion of total species | Minute (several hundred species) | Not yet established (likely to be minute) | Hill, 1977/current article |

| Association with human activity | Evolution and ecology have been strongly favoured by land disturbance that creates and open (plant) habitatsi | Evolution is likely to have occurred primarily in nature; but habitat dominance is commonplace in both natural and manmade environments | Anderson, 1952; Hill, 1977/Fig. 2; Table S1 and g |

| Problematic for human endeavours | Yes, due to loss of crop-plant yieldsj; toxicity/harm to livestock; role as hosts for crop pests and diseases, etc. | Yes, due to spoilage of foods, drinks; some species are pathogens of crop plants, livestock or humans; may emerge to take over industrial fermentations and other processesk | Hill, 1977/Table S1 |

| Value to humankind | Disproportionately important (origin of many crop-plant species; plant weeds have food value for humans or livestock; model organisms for research) | Disproportionately important (key sources of bulk chemicals and antimicrobialsl; for food and drinks production, and other biotechnological applications) | Hill, 1977; Koornneef and Meinke, 2010/; see Concluding remarks |

Typical traits.

Plant weeds may not be the dominating plant species.

Not necessarily the primary habitat of the microbial weed species.

Vigour can result from a combination of traits such as fast growth, stress tolerance, and immunity to toxins and diseases (see Tables 2–6).

Plant weeds typically have a high output of seeds under both favourable and poor growth-conditions, and can produce seed early (prior to maturity of the parent plant; Hill, 1977).

Each microbial weed species may secrete diverse antimicrobial substances which can be the primary factor in habitat dominance (see Table 7; Hallsworth, 1998; Walker, 2011). For examples of the concentrations at which moderately chaotropic stressors, potent chaotropes and hydrophobic stressors can inhibit cellular systems see Bhaganna and colleagues (2010). Toxins such as antibiotics, and VOCs, biosurfactants, and other stressors can have additional key roles in the cellular biology and ecology of microbes.

Some stressors of biotic origin are structurally identical to and/or exert the same stress mechanisms as stressors of abiotic origin (e.g. see Fig. 2; Tables 2–4 and 6).

Agricultural practices and crop-plant life-cycle can also select for early seed production and other weed traits (Hill, 1977).

Crop-yield losses caused by plant weeds are equivalent to those caused by plant pests or plant diseases (Cramer, 1967).

Open (microbial) habitats are not only the starting point for food and drinks fermentations, but many foodstuffs themselves represent open habitats and it is frequently microbial weed species that cause spoilage and therefore determine shelf-life. Open habitats located on and within host organisms can be readily invaded by microbial weed species including those with pathogenic activities (Cerdeño-Tárraga, et al., 2005). This has given rise to the use of probiotics (Molly et al., 1996; Bron et al., 2012) and a practice of preserving the skin microflora in babies and infants by avoiding use of soaps or detergents (Capone et al., 2011).

Antimicrobial substances are used for various applications; as biofuels, biocides, pharmaceuticals, flavour compounds, food preservatives, etc.

This article focuses on the following questions: (i) what types of substrate or environment facilitate the emergence of dominant microbial species, (ii) are there archetypal weed species that can consistently dominate microbial communities, (iii) what are the stress biology, nutritional strategies, energy-generating capabilities, antimicrobial activities and other competitive strategies of microbial weeds, (iv) which components and characteristics of microbial cells form the mechanics of weed biology, (v) what are the properties of open (microbial) habitats that promote the emergence of weed species, and (vi) how are microbial weeds conceptually distinct from plant weeds, and other ecophysiological groups of microorganism?

Dominance within microbial communities

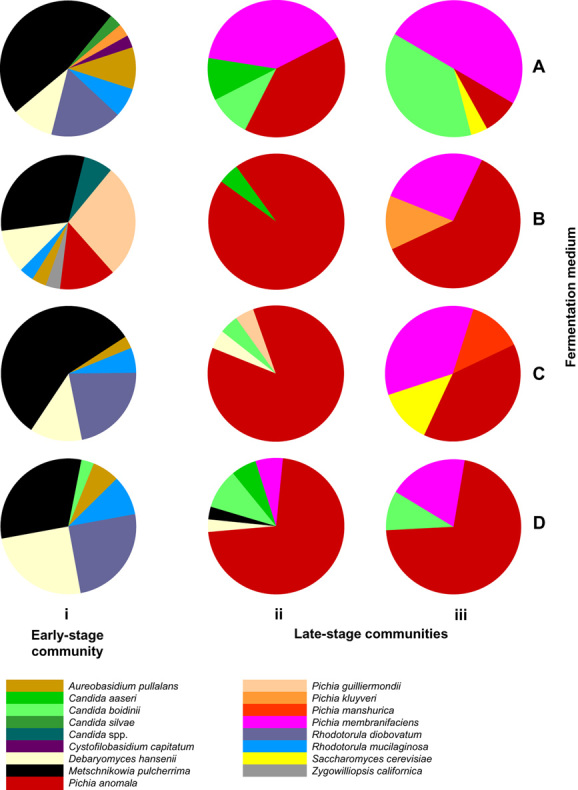

The microbial diversity of specific habitats, as well as that of Earth's entire biosphere, is an area of intensive scientific interest that has implications within the fundamental sciences and for drug discovery, biotechnology and environmental sustainability. Biodiversity provides the material basis for competition between microbial taxa, species succession in communities, and other aspects of microbial ecology that collectively impact the evolution of microbial species (Cordero et al., 2012). We believe that certain microbes are genetically, and thus, metabolically hard-wired to dominate communities (monopolizing available resources and space) and thereby reduce biodiversity within the habitat. Microbial communities can reach a stationary-phase or climax condition with a relatively balanced species composition (McArthur, 2006). However whether tens or thousands of microbial species are initially present (Newton et al., 2006) the community can become dominated by a single – or two to three – species (Fig. 1; Table S1; Randazzo et al., 2010; Cabrol et al., 2012). For example the indigenous microflora of olives is comprised of significant quantities of phylogenetically diverse species such as Aureobasidium pullulans, Candida spp., Debaryomyces hansenii, Metschnikowia pulcherrima, Pichia guilliermondii, Pichia manshurica, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and Zygowilliopsis californica (Fig. 1Bi; Nisiotou et al., 2010). Nisiotou and colleagues (2010) found that species succession and the stationary-phase community during olive fermentations are determined by one dominating genus, Pichia, three species of which account for almost 100% of the community by 35 days (see Fig. 1Biii). The most prevalent of these, Pichia anomala, is a microbial generalist that is not only able to inhabit ecologically and nutritionally distinct environments (e.g. palm sugar, cereals, silage, oil-contaminated soils, insects, skin, various marine habitats; see Walker, 2011) but can also dominate the communities that develop in diverse habitat types (Table S1; Tamang, 2010; Walker, 2011). Studies of Pecorino Crotonese cheese fermentations reveal that, even though the curd contains > 300 bacterial strains, the community is eventually dominated by Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Randazzo et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Percentage species composition during olive fermentations at (i) 2 days, (ii) 17 days and (iii) 35 days over a range of conditions: (A) with added NaCl (6% w/v); (B) added NaCl and glucose (6% and 0.5% w/v respectively); (C) added NaCl and lactic acid (6% w/v and 0.2% v/v respectively); and (D) NaCl, glucose and lactic acid (6% and 0.5% w/v, and 0.2% v/v respectively). Data (from Nisiotou et al., 2010) were obtained by DGGE.

Species that are able to dominate communities that develop in open habitats are not restricted to copiotrophs, generalists or any established ecophysiological grouping of microorganism (Table S1). Furthermore dominating species span the Kingdoms of life and, collectively, can be observed in most segments of the biosphere; from bioaerosols to solar salterns, oceans and freshwater to sediments and soils, the phyllosphere and rhizosphere, to those with molar concentrations of salts or sugars (see Table S1). The phenomenon can also be observed during food-production, food-spoilage and waste-decomposition processes where resource-rich habitats are available for colonization (see Table S1). The materials present in and the microbes living on these substrates are ultimately derived from the natural environment so community successions resulting in single-species dominance are likely to be commonplace in comparable open habitats within natural ecosystems (Table S1; Senthilkumar et al., 1993; Nisiotou et al., 2007; Reynisson et al., 2009; Rajala et al., 2011). Microbial weed species are able to dominate open habitats that progress to a closed condition (e.g. fermenting fruit juice) as well as those that remain in a more or less perpetually open state (e.g. the surface-fluid film of sphagnum moss and rhizosphere of plants growing in moist soils); see Table S1. Weeds emerge in habitats where competing cells are in close proximity (such as biofilms; Table S1; Rao et al., 2005) as well as those where there is limited mechanical contact between cells, such as the aqueous habitats of planktonic species (Table S1; Collado-Fabbri et al., 2011; Trigal et al., 2011; Leão et al., 2012); and in both extreme and non-extreme environments (Table S1). Some microbes emerge as a/the dominating species in diverse types of habitat including specialists such as Lactobacillus (that do so, in part, by acidifying their environment) and generalists such as Aspergillus, Pichia and Pseudomonas species (Table S1; Steinkraus, 1983; Tamang, 2010). For weed species such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (high-sugar environments), Haloquadratum walsbyi (aerobic, hypersaline brines), and Gonyostomum semen and Microcystis aeruginosa (eutrophic freshwater) ability to dominate can be restricted to a specific type of habitat. Most of these microbes do not populate their respective habitat as a one-off or chance event; they can consistently dominate their microbial communities and do so regardless of their initial cell number (Table S1; for P. anomala see Fig. 1; for S. cerevisiae see Pretorius, 2000; Renouf et al., 2005; Raspor et al., 2006; for L. rhamnosus see Randazzo et al., 2010). It is therefore intriguing to consider what combination(s) of traits can give rise to a weed phenotype.

Cellular biology of microbial weeds

Stress tolerance and energy generation

During habitat colonization, even in apparently stable, homogenous environments such as sugar-based solutions, there are dynamic/drastic changes in stressor concentrations, antimicrobials and stress parameters (D'Amore et al., 1990; Hallsworth, 1998; Eshkol et al., 2009; Fialho et al., 2011; see also below). As a result of these fluctuations microbes are exposed to multiple stresses some of which present potentially lethal challenges to the cell. In soil and sediments, for example the water activit can oscillate from low to high and high to low; these substrates typically cycle between desiccation and rehydration and are subjected to changes in solar radiation, temperature, and even freezing and thawing. Soils and sediments can be physically heterogeneous such that water availability, solute concentrations and other stress parameters exhibit profound spatial fluctuations. In addition, intracellular metabolites and extracellular substances (of both biotic and abiotic origin) impose stresses due to ionic, osmotic, chaotropic, hydrophobic and other activities of solutes (see Brown, 1990; Hallsworth et al., 2003a; 2007; Lo Nostro et al., 2005; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2010). On the one hand resilience to stress undoubtedly contributes to competitive ability but on the other a vigorous growth phenotype and reinforced stress biology also require extraordinary levels of energy generation. Furthermore, microbes that can achieve a greater net gain in energy than competing species will have an ecological advantage (Pfeiffer et al., 2001). Here we suggest that species able to dominate microbial communities are exceptionally well equipped to resist the effects of multiple stress parameters, and that many have high-efficiency energy-generation systems.

We tested the hypothesis that microbial weeds are exceptionally tolerant to habitat-relevant stresses for two species; the soil bacterium Pseudomonas putida (Table 2) and the specialist yeast S. cerevisiae (see below). Environments in which P. putida is a major ecological player (Table S1) typically contain an array of chemically diverse aromatics and hydrocarbons that induce chaotropicity-mediated stresses (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Cray et al., 2013). This bacterium is not only renowned for its metabolic versatility, but is also known for its tolerance to specific solutes and solvents (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Domínguez-Cuevas et al., 2006; Bhaganna et al., 2010). We compared the biotic windows for growth of P. putida for eight mechanistically distinct classes of stress using 37 habitat-relevant substances (Table 2). This bacterium was able to tolerate all substances within each group of stressor; this is the first data set to demonstrate that a mesophilic bacterium can tolerate the following combination of stresses: up to 4–11 mM hexane, toluene and benzene; 8–115 mM concentrations of aromatic, chaotropic solutes; 300–825 mM chaotropic salts; 1300–2160 mM sugars or polyols; 200–750 mM kosmotropic salts; and considerable levels of matric stress (Brown, 1990) generated by kosmotropic polysaccharides (Table 2). The P. putida tolerance limits to highly chaotropic substances and hydrophobic compounds were superior to those of other microbes (including extremophiles and polyextremophiles; Table 2; Hallsworth et al., 2007; Bhaganna et al., 2010). Whereas prokaryotes are generally less tolerant to solute stress than eukaryotes (Brown, 1990), the resilience to this array of mechanistically diverse solute stresses (Table 2) has neither been equalled nor been surpassed by any microbial species to our knowledge.

Table 2.

Growth windows for Pseudomonas putida under habitat-relevant stresses.a

| Stressor concentration (mM) causing P. putida growth-rate inhibition of: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stressor | Specific examples | 50%b | 100%b | Notes and references |

| Hydrophobic compoundsc | 1,2,3-Trichlorobenzened | 0.20 | 0.40 | Pseudomonas putida can be exposed to hydrophobic stressors in plant exudates, hydrocarbon-contaminated environments, and as hydrophobic catabolites and antimicrobials from P. putida or other microbes (see Table6; Timmis, 2009; Bhaganna et al., 2010) |

| γ-Hexachlorocyclohexaned,e | 0.00034 | 0.00072 | ||

| 2,5-Dichlorophenold | 0.70 | 0.90 | ||

| n-hexaned | 0.45 | 0.71 | ||

| Toluened | 4.0 | 4.6 | ||

| Benzened | 8.4 | 11.0 | ||

| Surfactants and aromatic solutes (highly chaotropic) | Tween® 80f,g | 108 | 164 | Cells come into contact with biosurfactants of microbial origin, and with chaotropic aromatics from the sources listed above (see also Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Timmis, 2009; Bhaganna et al., 2010) |

| Phenolh | 9.0 | 13.0 | ||

| o-cresole | 3.82 | 8.10 | ||

| Benzyl alcoholh | 20.0 | 32.7 | ||

| Sodium benzoatee | 69.2 | 115 | ||

| Chaotropic salts | CaCl2e | 210 | 302 | Chaotropic salts occur in soils, sediments, evaporite deposits, the Dead Sea, brine lakes (including the Discovery Basin located beneath the Mediterranean Sea and the Don Juan Pond in the Antarctic) and marine-associated habitats including bitterns (see Table S1); can be highly stressful for, and lethal to, microbial systems (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; 2007; Duda et al., 2004) |

| MgCl2d | 182 | 311 | ||

| Guanidine-HClh | 125 | 640 | ||

| LiClh | 595 | 825i | ||

| Alcohols and amides (moderately chaotropic) | Butanold | 158 | 208 | Alcohols are produced by some species as antimicrobials (Table6); ethanol is used as a biocide and can occur as an anthropogenic pollutant. Urea may be produced as an antimicrobial by some bacteria (Table6) and is used as an agricultural fertilizer to which soil bacteria are exposed |

| Ethanolh | 600 | 993i | ||

| Ureah | 650 | 950 | ||

| Formamided | 168 | 1080i | ||

| Relatively neutral substances | Methanold | 970 | 1440 | Some organic compounds have little chao- or kosmotropic activity at biologically relevant concentrations. At low concentrations glycerol is relatively neutral but, despite its role as a stress protectant, can act as a chaotropic stressor at molar concentrations (Williams and Hallsworth, 2009) |

| Ethylene glycolh | 1300 | 2160i | ||

| Glucosej | 840 | 1400 | ||

| Glycerolj | 770 | 2120i | ||

| Maltosej | 326 | 1300 | ||

| Kosmotropic compatible solutes | Prolinej | 800 | 2000 | The majority of microbial compatible solutes are kosmotropic, including other compatible solutes found in P. putida and other bacteria such as mannitol, betaine and ectoine. Pseudomonas may also come into contact with some of these compounds via exposure to plant exudates |

| Sorbitolj | 503 | 1200 | ||

| Dimethyl sulfoxidej | 353 | 1300 | ||

| Trehalosej | 474 | 771 | ||

| Glycinej | 99 | 370 | ||

| Betainej | 1570 | 2560 | ||

| Kosmotropic salts | NaClj | 650 | 750 | NaCl is environmentally ubiquitous, and is the dominant salt in most marine habitats including bioaerosols (Table S1); ammonium sulfate and KH2PO4 are commonly applied to soils as fertilizers. In many habitats kosmotropic salts are the primary osmotic stressors, but stresses imposed on the cell are determined by the net combination of solute activities of ions and other substances present (see Hallsworth et al., 2007) |

| KH2PO4j | 118 | 200 | ||

| Ammonium sulfatej | 198 | 350 | ||

| Sodium citratej | 53 | 500 | ||

| Polysaccharides (kosmotropic) | Dextran 40000j | 10 | 17 | Pseudomonas putida is exposed to the kosmotropic activities of and/or matric stress induced by polysaccharides such as microbe- and plant-derived extracellular polymeric substances, humic substances, etc. |

| Polyethylene glycol 3350j | 43 | 120 | ||

| Polyethylene glycol 6000j | 20 | 40 | ||

Pertinent to the phyllosphere, rhizosphere, hydrocarbon-polluted environments, and other habitats (see Table S1), including catabolic products of hydrocarbon degradation, antimicrobial substances (see Table 6), compatible solutes, and other P. putida metabolites. At sufficient concentrations solutes such as glucose, maltose, proline, sorbitiol, glycine, betaine, NaCl and KH2PO4 induce osmotic stress; whereas dextran and high Mr polyethylene glycols induce matric stress (see Brown, 1990); hydrophobic substances typically induce a (chaotropicity-mediated) hydrocarbon-induced water stress (Bhaganna et al., 2010; Cray et al., 2013); and other aromatics, alcohols, amides and specific salts cause chaotrope-induced water stress (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Cray et al., 2013).

Relative to no-added stressor controls (see Hallsworth et al., 2003a).

These data were taken from Bhaganna and colleagues (2010); P. putida KT2440 (DSMZ 6125) was grown in a minimal mineral-salt broth (with glucose and NH4Cl as the sole carbon and nitrogen substrates respectively; see Hartmans et al., 1989; Bhaganna et al., 2010) at 30°C. The media for control treatments had no stressors added. Some P. putida strains can tolerate benzene at up to 20 mM (Volkers et al., 2010).

The pesticide γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH) is also known as lindane.

Pseudomonas putida KT2440 was grown in modified Luria–Bertani broth at 30°C; stressors were incorporated into media prior to inoculation, and growth rates calculated, as described by Hallsworth and colleagues (2003a). The media for control treatments had no stressors added.

Tween® 80 was used as a model substitute for biosurfactants (Cray et al., 2013).

These data were taken from Hallsworth and colleagues (2003a); P. putida KT2440 was grown in modified Luria–Bertani broth at 30°C as described in footnote (f).

Extrapolated values.

Glycerol is a notable exception (Williams and Hallsworth, 2009).

Pseudomonas putida is able to avoid contact with or prevent accumulation of stressors by using solvent-efflux pumps and synthesizing extracellular polymeric substances to form a protective barrier (Table 3). This bacterium also utilizes highly efficient macromolecule-protection systems that are upregulated in response to multiple environmental stresses including between 10 and 20 protein-stabilization proteins, oxidative-stress responses, and upregulation of energy generation and overall protein synthesis (Table 3). Furthermore, P. putida can synthesize an array of compatible solutes including betaine, proline, N-acetylglutaminylglutamine amide, glycerol, mannitol and trehalose (Table 3). Individual compatible solutes are unique in their physicochemical properties, interactions with macromolecular systems and functional efficacy for specific roles within the cell (e.g. see Chirife et al., 1984; Crowe et al., 1984; Brown, 1990; Hallsworth and Magan, 1994a; 1995; Yancey, 2005; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2013). Microbes that are able to selectively utilize/deploy any substance(s) from a range of diverse compatible solutes have enhanced tolerance to diverse stresses (e.g. Hallsworth and Magan, 1995; Bhaganna et al., 2010). The range of compatible solutes utilized by P. putida may be unique for a bacterium (see Brown, 1990) and can confer tolerance to diverse stresses including those imposed by chaotropes and hydrocarbons (Bhaganna et al., 2010).

Table 3.

Stress tolerance and energy generation: cellular characteristics that contribute to weed-like behaviour.a

| Metabolites, proteins, molecular characteristics, and other traits | Function(s) | Phenotypic traits | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerances to multiple environmental stresses | |||

| Ability to select from an array of functionally diverse compatible solutes in response to specific stress parameters | Specific compatible solutes can protect against osmotic stress, temperature extremes, freezing, dehydration and rehydration, chaotropicity, and/or hydrophobic stressors (Crowe et al., 1984; Brown, 1990; Hallsworth et al., 2003b; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2010; Bell et al, 2013) | Ability to maintain functionality of macromolecular systems and/or cell turgor under diverse stresses | Some microbes utilize a wide array of compatible solutes depending on the type and severity of stress; e.g. Pseudomonas putida is exceptional among bacteria in its ability to synthesize and accumulate protectants as diverse as betaine, proline, N-acetylglutaminylglutamine amide, glycerol, mannitol and trehalose (D'Souza-Ault et al., 1993; Kets et al., 1996; Bhaganna et al., 2010); Saccharomyces cerevisiae can accumulate proline, glycerol and trehalose (see Table6; Kaino and Takagi, 2008). Like other fungi, Aspergillus species utilize a range of polyols as well as trehalose (Hallsworth and Magan, 1994c; Hallsworth et al., 2003b) but their exceptional ability to generate energy under stress (see below) may aid glycerol retention and thereby extending the growth window at low water activity (Hocking, 1993; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009) |

| Upregulation of protein-stabilization proteins in combinations tailored to specific stressesb | In addition to stressors (including those of biotic origin; Table6), protein-stabilization proteins also protect against perturbations induced by stresses such as temperature extremes and desiccation (Arsène et al., 2000; Ferrer et al., 2003) | Maintenance of protein structure and function during environmental challenges | Several studies show highly efficient responses of P. putida to chaotropic and hydrophobic stressors via upregulation of between 10 and 20 protein-stabilizing proteins (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Santos et al., 2004; Segura et al., 2005; Domínguez-Cuevas et al., 2006; Tsirogianni et al., 2006; Volkers et al., 2006; Ballerstedt et al., 2007). The PalA protein in Aspergillus nidulans induces a rapid upregulation of protein-stabilization proteins in response to extreme pH (Freitas et al., 2011); high production rates of protein-stabilization proteins enhance tolerance to chaotropic salts and alcohols in S. cerevisiae and Lactobacillus plantarum, to hydrophobic stressors in S. cerevisiae and Escherichia coli (for references, see Bhaganna et al., 2010), and low temperature, salt and other stresses in Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (Lahav et al., 2004) |

| Intracellular accumulation of ions for osmotic adjustment; intracellular proteins structurally adapted to high ionic strength | The utilization of ions for osmotic adjustment avoids the energy-expensive synthesis of organic compatible solutes (Kushner, 1978; Oren, 1999) | Ability to maintain metabolic activity at high extra- and intracellular ionic strength | Haloquadratum walsbyi, and Salinibacter ruber (unusually for a bacterium), utilize the so-called ‘salt-in’ strategy (Oren et al., 2002; Bardavid and Oren, 2012; Saum et al., 2012) |

| Diverse proteins and pathways conferring tolerance to solvents, chaotropic solutes and hydrophobic stressors | Solvent-tolerant species such as P. putida can function at high concentrations of chaotropic and hydrophobic stressors due to the collective activities of solvent pumps that expel solvent molecules, pathways that catabolize the solvent, membrane-stabilization proteins (see below), compatible solutes (see above), and additional chaotrope- and solvent-stress responses (Ramos et al., 2002; Timmis, 2002; Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Volkers et al., 2006; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Fillet et al., 2012) | High tolerance to chaotropic and hydrophobic solvent stressors | Due to its exceptional solvent tolerance P. putida is the organism of choice for many industrial applications including biotransformation in two-phase systems and bioremediation (Timmis, 2002). |

| Membrane-stabilization proteins; e.g. cis/trans-isomerase (CTI) | Membrane stabilization under stress | Enhanced tolerance to stresses that impact membrane structure | Several proteins are involved in maintaining bilayer rigidity in P. putida during exposure to toluene and other solvents or hydrophobic stressors (Bernal et al., 2007) |

| Proteins involved in the moderation of membrane fluidity | Maintenance of membrane fluidity and membrane-associated processes under conditions such as low temperature (Turk et al., 2011) | Enhanced tolerance to diverse, physicochemical stress parameters | For example Aureobasidium pullulans, Cryptococcus liquefaciens and R. mucilaginosa (Turk et al., 2011) |

| Promoter(s) that simultaneously control multiple stress-response genes, e.g. stress-response elements (STREs) | Activation of multiple cellular stress-responses | Enhanced tolerance to multiple stress-parameters | The transcription factors (Msn2p and Msn4p) involved in STRE-mediated stress responses in S. cerevisiae accumulate in the nucleus upon heat-, ethanol- (chaotrope-), and osmotically induced stresses, and during nutrient limitation. The STRE is upstream of genes for protein-stabilization proteins (see above) metabolic enzymes, and cellular organization proteins (Görner et al., 1998; Moskvina et al., 1998) |

| Proteins involved in DNA protection under stress; e.g. DNA-binding protein (Dps) | Formation of a protein:chromosome complex that protects DNA | Enhanced DNA stability and reduced risk of mutation in relation to multi-farious stresses | The role of Dps has been well-characterized in E. coli in relation to diverse environmental challenges including reactive oxygen species, iron and copper toxicity, thermal stress and extremes of pH (Nair and Finkel, 2004) |

| Pathways for synthesis of carotenoids (e.g. β-carotene in Dunaliella salina; torularhodin in Rhodotorula spp.) | Carotenoids absorb light and thereby protect cellular macromolecules and organelles from exposure to ultraviolet | Tolerance of exposure to ultraviolet irradiation | Synthesis of β-carotene is upregulated in response to light in D. salina (Chen and Jiang, 2009); carotenoids are concentrated in the plasma membrane of S. ruber (Antón et al., 2002); studies of R. mucilaginosa show that torularhodin enhances tolerance to ultraviolet B exposure (Moliné et al., 2010) |

| Preferential utilization of a chaotropic compatible solute at high NaCl concentration and/or low temperature | Rigidification of macromolecular structures at high NaCl and low temperature can induce metabolic inhibition (Brown, 1990; Ferrer et al., 2003; Chin et al., 2010) that can be compensated for by glycerol and/or fructose (Brown, 1990; Chin et al., 2010) | Enhanced tolerance to extreme conditions that rigidify macromolecular systems | The high intracellular concentrations of glycerol in D. salina under salt stress and glycerol and/or fructose in and Aspergillus and Eurotium spp. and R. mucilaginosa at low temperature are able to extend growth windows under these extreme conditions (Brown, 1990; Lahav et al., 2002; Chin et al., 2010). Dunaliella salina has membranes with reduced glycerol permeability thereby aiding retention of this compatible solute (Bardavid et al., 2008) |

| Efficient system to eliminate free radicals (see above) | Elimination of reactive oxygen species (see also Table5) | Various substances and stress parameters can induce oxidative stress | Diverse environmental substances and parameters induce oxidative stress, either directly or indirectly (e.g. via lipid peroxidation). For example, chaotropic stressors and heat shock have been associated with the induction of oxidative stress responses in S. cerevisiae and P. putida (Costa et al., 1997; Hallsworth et al., 2003a) |

| Proteins associated with regulation of cytosolic pH; e.g. the lysine decarboxylase system (coded for by the cadBA operon); the Na+/H+ antiporter | Conversion and export of lysine/cadaverine that results in increased pH of the cytosol in bacteria (Álvarez-Ordóñez et al., 2011); the Na+/H+ antiporter Nha1 decreases intracellular hydrogen ion concentration | Tolerance of low-pH environments | Decarboxylase systems that increase intracellular pH also exist for other amino acids (Álvarez-Ordóñez et al., 2011); Nha1 greatly enhances viability of Saccharomyces boulardii at pH 2 (dos Santos Sant'Ana et al., 2009) |

| Multidrug efflux pumps (for details see Table6) | |||

| Enzymes for synthesis of extracellular polymeric substances | Production and secretion of polymeric substances | Enhanced tolerance to multiple stressors and stress parameters | Extracellular polymeric substances have been shown to confer protection to E. coli cells exposed to high temperature, low pH, salt and oxidative stress (Chen et al., 2004), and are associated with stress protection in Clostridium spp., Pantoea ananatis, P. putida and other Pseudomonas spp. (Chang et al., 2007; Morohoshi et al., 2011; see also Table 6) |

| Upregulation of proteins involved in protein synthesis under stress | To enhance or maintain the quantity, type, and functionality of cellular proteins under stress | Maintenance of the cellular system and its metabolic activity under stress | Can be upregulated in response to stress induced by high temperature, chaotropic solutes, hydrophobic stressors and other stress parameters (e.g. P. putida; Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Volkers et al., 2009) |

| Polyploidy, aneuploidy, association with plasmids, and/or hybridization that enhance(s) stress tolerance | Whereas hybridization, polyploidy, aneuploidy and association with plasmids can be ecologically disadvantageous, such traits can enhance the vigour, stress tolerance and competitive ability of some microbes such as Pichia spp., S. cerevisiae, P. putida and S. ruber (Table1; Rainieri et al., 1999; Naumov et al., 2001; Mongodin et al., 2005; Tark et al., 2005; Dhar et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012) | Enhanced stress tolerance | Aneuploid cells of S. cerevisiae have enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress and diverse inhibitors of biochemical processes (Chen et al., 2012); polyploidy can enhance vigour and stress tolerance in some species (see also Tables1 and c); the stress tolerance of some microbial weeds is enhanced by their association with plasmids (e.g. the P. putida tol-plasmid that enhances solvent tolerance; Tark et al., 2005; Domínguez-Cuevas et al., 2006; the S. ruber plasmid contains a gene involved in ultraviolet protection; Mongodin et al., 2005) |

| Polyextremophilic growth-phenotype | Ability to grow optimally under multiple, extreme conditions; e.g. extremely acid and alkali (pH 2–10), high-salt (2.5 M NaCl), and low-temperature conditions (Lahav et al., 2002; Libkind and Sampaio, 2010) | Polyextremophile | Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is capable of growth over an incredible range of physicochemical conditions (including almost the entire pH range for microbial life) and is able to colonize a correspondingly wide diversity of environments (for examples see main text) |

| Genes associated with salt stress | Sugar catabolism (e.g. RmPGM2, RmGPA2, RmACK1, RmMCP1 and RmPET9), protein glycosylation (e.g. RmSEC53), aromatic amino acid synthesis (e.g. RmARO4), regulation of protein synthesis (e.g. RmANB1) | Maintenance of protein synthesis and energy generation under salt stress | Between 10 and 20 genes are involved in increased tolerance to NaCl and/or LiCl in R. mucilaginosa (Lahav et al., 2004; Gostinčar et al., 2012) |

| Metabolites associated with resistance to antimicrobial plant metabolites and survival in phyllosphere habitats | Metabolites involved in quorum sensing may enhance competitive ability on the leaf surface | Enhanced survival and competitive ability | By contrast to other phyllosphere microbes, P. ananatis is resistant to the inhibitory effects of plant alkaloids and this correlates with the production of metabolites involved in quorum sensing such as N-acyl-homoserine lactone (Enya et al., 2007) |

| High-efficiency energy-generation systems | |||

| Light-activated proton pumps (e.g. xanthorhodopsin) | To generate a proton-motive force, utilizing light as an energy source | Utilization of light for transmembrane proton transport | Xanthorhodopsin, found in S. ruber, is a proton pump made up of two chromophores; a light-absorbing carotenoid and a protein (Balashov et al., 2005); a light-activated proton pump was also recently described in H. walsbyi (Lobasso et al., 2012) |

| High expression of genes involved in energy generation (e.g. fba, pykF, atpA and atpDc) | Rapid catabolism of carbon substrates leading to enhanced synthesis of ATP | Efficient energy-generation | High expression of E. coli genes fba, pykF, atpA and atpD can be associated with ability to grow rapidly, enhanced stress tolerance and – by implication – greater competitive ability (Karlin et al., 2001) |

| Enhanced energy-efficiency at low nutrient concentrations (e.g. see glutamate dehydrogenase entry in Table5) | |||

| Upregulation of proteins involved in energy generation under chaotropic and solvent-induced (hydrocarbon) stresses (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Volkers et al., 2006). | Maintenance of energy generation close to the point of system failure under hostile conditions | Efficient energy generation during potentially lethal challenges | The exceptional ability of P. putida to respond and adapt to chaotropic, solvent and hydrocarbon stressors has, in part, been attributed to considerable increases in energy- and NAD(P)H-generating systems |

| Idiosyncratic genome modifications associated with reinforced energy metabolism | Enhanced primary metabolism and energy-generation systems | Enhanced vigour and energy production | Aspergillus species have numerous genome modifications, such as gene duplications for pyruvate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, aconitase and malate dehydrogenase that enhance primary metabolism including glycolysis and the TCA cycle (Flipphi et al., 2009) |

| Efficient utilization of intracellular reserves for energy generation | Catabolism of stored substances to boost growth, stress tolerance, production of secondary metabolites, motility and/or other key cellular functions under stress | Ability to maintain energy production during nutrient limitation and under hostile conditions | Efficient storage (see Table5) and utilization of energy-generating substances such as trehalose, glycogen and polyhydroxyalkanoates confers a competitive advantage in S. cerevisiae and other species (Castrol et al., 1999; Kadouri et al., 2005) |

| Concomitant energy generation and synthesis of antimicrobials with no loss of ATP-generation efficiency | Via aerobic fermentation S. cerevisiae can simultaneously generate energy while synthesizing the chaotropic stressor ethanol (see Table6) | Energy generation linked to synthesis of an antimicrobial | Each glucose molecule fermented by S. cerevisiae produces two ethanol molecules and two molecules of ATP (Piškur et al., 2006) |

The current table provides examples of proteins, genes or other characteristics that can be associated with and give rise to weediness; the categories of traits are not mutually exclusive. Individual traits may not be unique to microbial weeds; however, weeds species are likely to have a number of these types of characteristics.

For example chaperonins, heat-shock proteins and cold-shock proteins.

That code for fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, pyruvate kinase and ATP synthase subunits F1 α and F1 β respectively.

The exceptionally wide growth-windows of Aspergillus species in relation to a number of stress parameters correlate with their ability to dominate communities in both extreme and non-extreme (but physicochemically dynamic) environments including soils, plant necromass, saline and very high-sugar habitats (Table S1). At least 20 species of Aspergillus and the closely related genus Eurotium are xerotolerant (Pitt, 1975; Brown, 1990). Aspergillus penicillioides is capable of hyphal growth and conidial germination down to water activities of 0.647 and 0.68 respectively (Pitt and Hocking, 1977; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009); Aspergillus echinulatus can germinate down to 0.62 (Snow, 1949). Halotolerant species such as Aspergillus wentii can grow on the highly chaotropic salt guanidine-HCl at a higher concentration than any other microbe; up to 930 mM (≡ 26.5 kJ g−1 chaotropic activity; Hallsworth et al., 2007) and, along with Aspergillus oryzae, up to ∼ 4 M NaCl or KCl (Hallsworth et al., 1998). Aspergillus (and Eurotium) strains are capable of reasonable growth rates close to 0°C (Chin et al., 2010), and some reports suggests that the biotic windows for some Aspergillus species ultimately fail at ≤ −18°C (Vallentyne, 1963; Siegel and Speitel, 1976). Whereas a number of comparable fungal genera show moderate levels of stress tolerance, Aspergillus species generally out-perform their competitors and top numerous league tables for ascomycete stress tolerance (see Pitt, 1975; Wheeler and Hocking, 1993; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009).

Studies of seven Aspergillus species have revealed a number of genome modifications within this genus that reinforce both primary metabolism and energy generation (Table 3; Flipphi et al., 2009). These include gene duplications for key enzymes that control metabolic flux, such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, aconitase, and malate dehydrogenase that enhance glycolysis and the TCA cycle (Flipphi et al., 2009). There is evidence that, at the low water activities (high osmotic pressures) associated with very high-salt and high-sugar habitats, the biotic window of xerophilic fungi fail due to the prohibitive energy expenditure required to prevent the high levels of intracellular glycerol from leaking out of the membrane (Hocking, 1993). The adaptability and competitive ability of Aspergillus species (most of which can also proliferate under non-extreme conditions) may be attributed, in part, from enhanced energy-generating capability. Aspergillus species (like many fungi) can utilize a range of polyols – as well as trehalose – as compatible solutes based on their individual strengths as protectants against osmotic stress, desiccation rehydration, chaotropes etc. (Crowe et al., 1984; Brown, 1990; Hallsworth et al., 2003b). Aspergillus and Eurotium strains can also accumulate chaotropic sugars from the medium, or preferentially synthesize and accumulate chaotropic glycerol, in order to enhance growth at temperatures below ∼ 10°C (Chin et al., 2010; see also below).

Salinibacter ruber is a halophilic bacterium found in high numbers at molar salt concentrations in aerobic aquatic habitats that are otherwise more densely populated by archaeal than bacterial species. Unusually for a bacterium, S. ruber takes in ions to use as compatible solutes and thereby avoids synthesis of organic compatible solutes that would be energetically unfavourable in environments of > 1 M NaCl (Oren, 1999) and has evolved intracellular proteins that are both structurally stable and catalytically functional in the cytosol at high ionic strength (Table 3). Salinibacter ruber (as well as the alga Dunaliella salina and yeast R. mucilaginosa) accumulates carotenoids in response to light which can protect against oxidative stress that is a potential hazard in salterns exposed to high levels of ultraviolet (Table 3). Haloquadratum walsbyi, an Archaeon that is also a dominant player in saltern communities (Table S1), also uses the ‘salt-in’ compatible-solute strategy, and – along with S. ruber – has light-activated protein pumps that generate proton-motive force and thereby boost energy generation (Table 3). In addition, H. walsbyi is unusually tolerant to the chaotropic salt MgCl2 that can reach high concentrations in evaporate ponds (Hallsworth et al., 2007; Bardavid et al., 2008). Dunaliella salina is also highly prevalent in saline habitats that (unusually for an alga) can successfully compete with the multitude of halophilic Archaea found in 5 M NaCl environments (see later; Table S1). This alga preferentially utilizes glycerol as a compatible solute, is able to accumulate glycerol to molar concentrations (6–7 M; see Bardavid et al., 2008), and has low membrane permeability to this compatible-solute thus aiding retention (Bardavid et al., 2008).

Glycerol is unique in its ability to maintain the flexibility of macromolecular structures under conditions that would otherwise cause excessive rigidification, e.g. molar concentrations of NaCl, or low temperature (Back et al., 1979; Hallsworth et al., 2007; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009; Chin et al., 2010). Species able to grow at low or subzero temperatures (e.g. Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula species, including R. mucilaginosa) either primarily use glycerol as a compatible solute or preferentially accumulate this chaotrope at low temperature (Table 3; Lahav et al., 2004; Chin et al., 2010). Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is able to colonize – and frequently dominates – diverse substrates/environments including saline and non-saline soils, aquatic habitats (both liquid- and ice-associated), the acidic surface-film of sphagnum moss (as well as other plant tissues) and various surfaces within the human body and other animals (Table S1; Egan et al., 2002; Trindade et al., 2002; Vital et al., 2002; Lahav et al., 2002; 2004; Lisichkina et al., 2003; Buzzini et al., 2005; Perniola et al., 2006; Goyal et al., 2008; Turk et al., 2011; Kachalkin and Yurkov, 2012). This ability is coupled with an exceptional level of tolerance to multiple stresses: R. mucilaginosa is (highly unusual for a yeast) a polyextremophile that is psychrophilic, highly salt-tolerant, and can growth over the majority of the pH range known to support microbial life (i.e. < 2 and > 10, see Table 3; Lahav et al., 2002).

Some microbial habitats such as fruits that have been disconnected from the vascular system (and immune responses) of the parent plant have a favourable water activity and high nutrient availability and are therefore potentially habitable by a wide range of microbes (Ragaert et al., 2006). As the microbial community develops on a detached fruit (or in apple or grape musts; see Table S1) there can be changes in the composition and concentration of sugars, osmolarity, water activity, ethanol concentration (and that of other antimicrobials), pH and other environmental factors that are severe enough to inhibit or eliminate most members of the original microflora (see Brown, 1990; Hallsworth, 1998; de Pina and Hogg, 1999; Pretorius, 2000; Bhaganna et al., 2010). The yeast S. cerevisiae that is relatively scarce in natural habitats (and even when present forms a quantitatively insignificant component of the natural community; Renouf et al., 2005; Raspor et al., 2006) is unsurpassed in its ability to emerge to dominate high-sugar habitats at water activities above 0.9 (Table S1; Hallsworth, 1998; Pretorius, 2000). We therefore compared its tolerance towards a range of habitat-relevant stressors with those of 12 other yeasts that occur at the insect–flower interface, on plant tissues, and/or are environmentally widespread (Fig. 2; Table 4). This experiment revealed that S. cerevisiae has a more vigorous growth phenotype and more robust stress tolerance than the other species tested with the exception of two species of Pichia, another genus characterized by weed-like traits (see Fig. 2; Table 4). Stress phenotypes of the yeasts assayed were compared on the basis of stressor type and mechanistically distinct stress-parameters in order to assess resilience to both the degree and diversity of environmental challenges (Table 4). Under the assay conditions it was the three S. cerevisiae strains, Pichia (Kodamaea) ohmeri and Pichia sydowiorum that exhibited the greatest tolerance to the widest range of solute-imposed stresses (Table 4). Other species studied were slow growers, have specific environmental requirements (e.g. the halotolerant D. hansenii and Hortaea werneckii), and/or otherwise lacked the capacity for vigorous growth on the high-sugar substrate at 30°C (see Fig. 2). Generally S. cerevisiae strains were fast-growing, xerotolerant, and highly resistant to chaotrope-induced, osmotic, matric and kosmotrope-induced stresses and are known to be acidotolerant and capable of growth over a wide temperature range, from ∼0°C to 45°C (Fig. 2A and B; Table 4). Although Pichia species can produce ethanol (P. anomala can produce up to 0.36 M ethanol; Djelal et al., 2005) when growing side by side in high-sugar habitats with S. cerevisiae, Pichia species are unable to tolerate the molar ethanol concentrations that S. cerevisiae can produce (Lee et al., 2011).

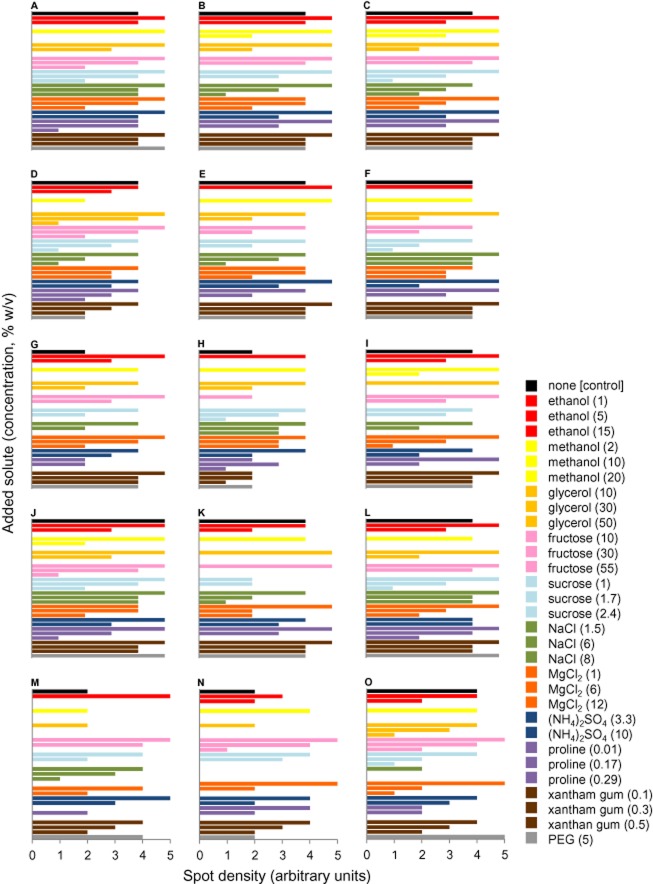

Figure 2.

Growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains: (A) CCY-21-4-13, (B) Alcotec 8 and (C) CBS 6412 and other yeast species: (D) Candida etchellsii (UWOPS 01–168.3), (E) Cryptococcus terreus (PB4), (F) Debaryomyces hansenii (UWOPS 05-230.3), (G) Hansenula (Ogataea) polymorpha (CBS 4732), (H) Hortaea werneckii (MZKI B736), (I) Kluyveromyces marxianus (CBS 712), (J) Pichia (Kodamaea) ohmeri (UWOPS 05-228.2), (K) Pichia (Komagataella) pastoris (CBS 704), (L) Pichia sydowiorum (UWOPS 03-414.2), (M) Rhodotorula creatinivora (PB7), (N) Saccharomycodes ludwigii (UWOPS 92–218.4) and (O) Zygosaccharomyces rouxii (CBS 732) on a range of media at 30°C. These were: malt-extract, yeast-extract phosphate agar (MYPiA) without added solutes (control), and MYPiA supplemented with diverse stressors – ethanol, methanol, glycerol, fructose, sucrose, NaCl, MgCl2, ammonium sulfate, proline, xantham gum and polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 – over a range of concentrations as shown in key (values indicate %, w/v). A standard Spot Test was carried out (see Chin et al., 2010; Toh et al., 2001) that was modified from Albertyn and colleagues (1994) for stress phenotype characterization (see Table 5). Colony density was assessed after an incubation time of 24 h on a scale of 0–5 arbitrary units (Chin et al., 2010). Cultures were obtained from (for strain A) the Culture Collection of Yeasts (CCY, Slovakia); (strain B) Hambleton Bard Ltd, Chesterfield, UK; (strains C, G, I, K, O) the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS, the Netherlands); (strains D, F, J, L, N) the University of Western Ontario Plant Sciences Culture Collection (UWOPS, Canada); (strains E, M) were obtained from Dr Rosa Margesin, Institute of Microbiology, Leopold Franzens University, Austria; and (strain H) the Microbial Culture Collection of National Institute of Chemistry (MZKI, Slovenia). All Petri plates containing the same medium were sealed in a polythene bag to maintain water; all experiments were carried out in duplicate, and plotted values are the means of independent treatments.

Table 4.

Stress phenotypes and ecophysiological profiles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae relative to those of other yeast species

| Tolerance to diverse stressorsb |

Tolerance to distinct stress mechanismsb |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast speciesa | Alcohols | Glycerol | Sugars | Salts | Others | Chaotropic | Osmotic | Matric | Kosmotropic | Additional notes on stress and growth phenotypesc | Typical habitat | Ecophysiological descriptiond |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain | ||||||||||||

| CCY-21-4-13 | Higher | Mid | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Topt 30–35°C; Tmin ∼0.5°C; Tmax 45°C pHopt 3–7; pHmin ∼2.5e; fast grower | Fruits; other fleshy plant tissues; nectar | Multiple stress tolerances including sugar and ethanolf; stress phenotype of a xerotolerant, acidotolerant, vigorous weed |

| Alcotec 8 | Higher | Mid | Mid | Mid | Higher | Higher | Mid | Higher | Mid | As above | As above | As above |

| CBS 6412 | Higher | Mid | Higher | Mid | Higher | Higher | Mid | Higher | Mid | As above | As above | As above |

| Other species (strain) | ||||||||||||

| Candida etchellsii (UWOPS 01–168.3) | Lower | Higher | Mid | Higher | Mixed | Higher | Higher | Mid | Mid | Slow growerg | Pollinating insects; flowers; fermented foods | Intolerant to specific stressors; slow-growing |

| Cryptococcus terreus (PB4) | Mid | Mid | Higher | Mid | Higher | Mid | Mid | Higher | Mid | Topt 10°C; Tmin 1°Ch; slow grower | Soils and sediments; subsurface environments | A slow-growing psychrophilei |

| Debaryomyces hansenii (UWOPS 05–230.3) | Mid | Mid | Higher | Higher | Higher | Mid | Mid | Higher | Lower | Topt 30–32°C; pHopt 5.5j; fast grower | High-salt environments and foods | Halotolerant; a fast-growing high-salt specialist |

| Hansenula (Ogataea) polymorpha (CBS 4732) | Higher | Mid | Mid | Mid | Higher | Higher | Lower | Higher | Higher | Topt 37–43°C; pHopt 4.5–5.5h | Soil, insect gut, fruit juice | Neither fast-growing nor highly stress tolerant; a high-temperature specialist |

| Hortaea werneckii (MZKI B736) | Mid | Mid | Higher | Higherj | Lower | Mid | Mid | Lower | Mid | Topt ∼29°Ch; slow grower | Salty environments; animal and plant surfaces | Intolerance to matric stress; a slow-growing halophile |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus (CBS 712) | Higher | Lower | Mid | Lower | Higher | Mid | Lower | Higher | Lower | Topt ∼38–40°C; Tmax 65°Ch; not fast-growing | Milk; plant surfaces; natural fermentations | Thermotolerant, solute-intolerant and xero-intolerantj |

| Pichia (Kodamaea) ohmeri (UWOPS 05–228.2) | Higher | Mid | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Mid | Topt ∼33°C; Tmax > 50°Ch; fast- grower | Beetles; fruits and other plant | Multiple stress tolerances including ethanol and sugar; stress phenotype of a xerotolerant, vigorous weed |

| Pichia (Komagataella) pastoris (CBS 704) | Mid | Lower | Lower | Mid | Higher | Mid | Lower | Higher | Mid | pHmin ∼2.2h; not fast-growing | Rotting wood; slimes | Intolerant to osmotic stress, glycerol and sugar; a xero-intolerant yeast |

| Pichia sydowiorum (UWOPS 03–414.2) | Higher | Mid | Higher | Higher | Higher | Higher | Mid | Higher | Higher | pHopt ∼6–8h; fast grower | Polluted environments; waste water | Multiple stress tolerances including ethanol and sugar; stress phenotype of a xerotolerant, vigorous weed |

| Rhodotorula creatinivora (PB7) | Lower | Lower | Mid | Mid | Lower | Lower | Lower | Mid | Higher | Topt ∼10°C; Tmin ∼1°Ch; slow grower | Subsurface; soil | Intolerant to alcohols, glycerol; xerotolerant a psychrophilic slow grower |

| Saccharomycodes ludwigii (UWOPS 92–218.4) | Lower | Mid | Higher | Lower | Lower | Lower | Lower | Lower | Lower | pHmin ∼2h; slow grower | Grapes; plant tissues and fermentations | Intolerant to glycerol and NaCl; tolerant to sugars; an osmophile |

| Zygosaccharomyces rouxii (CBS 732) | Mid | Higher | Higher | Lower | Mixed | Higher | Mid | Mid | Mid | pHopt 3–7; pHmin 1.5–2h; slow grower | Fruits and other high-sugar habitats | Intolerant to NaCl; tolerant to glycerol and sugars; an osmophile |

Sources of strains are given in Fig. 2.

Based on data for growth on MYPiA at 30°C (see Fig. 2). Alcohols were ethanol and methanol, sugars were fructose and sucrose, salts were NaCl, MgCl2 and ammonium sulfate, the other stressors were proline, xantham gum and PEG 8000 (Fig. 2). Chaotrope stress is induced by ethanol, fructose, glycerol and MgCl2; osmotic stress by fructose, sucrose, NaCl and proline; matric stress by xantham gum and PEG 8000; and kosmotrope stress by ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2; Brown, 1990; Hallsworth, 1998; Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Hallsworth et al., 2007; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2010; Cray et al., 2013). Stress-tolerance assessments (higher, mid-range, lower) are relative to the range of those of the other species assayed, and based on values in Fig. 2.

Temperature optima, minima and/or maxima (Topt, Tmin, Tmax) and pH optima, minima and/or maxima (pHopt, pHmin, pHmax) for growth were obtained from cited publications. Extreme growth phenotypes (fast or slow growers) were listed according to growth rates on MYPiA at 30°C (see also Fig. 2). Species designated as slow growers did not have a vigorous growth phenotype under these conditions; i.e. all strains listed are able to grow rapidly within the assay period on/at their favoured media/temperature. The designation slow growing did not relate to an extended lag phase (data not shown).

Primarily based on data presented in the current table as well as Fig. 2 (unless otherwise stated) so is most pertinent to high-sugar habitats at ∼30°C. Habitat dominance will ultimately be influenced by antimicrobial activities of species present within a community; see Table 6). Ecophysiological descriptions of weed-like species are underlined in bold.

Values for temperature- and pH-tolerances were taken from: (for S. cerevisiae) Praphailong and Fleet (1997), Yalcin and Ozbas (2008) and Salvadó and colleagues (2011); (for C. terreus) Krallish and colleagues (2006); (for D. hansenii) Domínguez and colleagues (1997); (for H. polymorpha) Levine and Cooney (1973); (for H. werneckii) Díaz Muñoz and Montalvo-Rodríguez (2005); (for K. marxianus) Aziz and colleagues (2009); Salvadó and colleagues (2011); (for P. ohmeri) Zhu and colleagues (2010); (for P. pastoris) Chiruvolu et al. (1998); (for P. sydowiorum) Kanekar and colleagues (2009); (for R. creatinivora) Krallish and colleagues (2006); (for S. ludwigii) Stratford (2006); and (for Z. rouxii) Restaino and colleagues (1983) and Praphailong and Fleet (1997). Tolerance windows for Candida etchellsii are yet to be established.

Under some conditions strains of S. cerevisiae can tolerate up to 28% v/v (20% w/v) ethanol (see Hallsworth, 1998).

See also Krallish and colleagues (2006).

In high-salt habitats, H. werneckii can grow at molar concentrations of NaCl (see Gunde-Cimerman et al., 2000) but was less salt tolerant under the conditions of this assay.

This species appears to have a requirement for high water activity.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is metabolically wired to concomitantly synthesize an antimicrobial chaotrope (ethanol), accumulate a compatible solute (glycerol) that affords protection against this chaotrope (see below), and at the same time generate energy without any loss of ATP-generation efficiency (Table 3): a remarkable phenotype that is coupled with the deployment of other compatible solutes under specific conditions (trehalose and proline). Trehalose, which can reach concentrations of up to 13% dry weight in S. cerevisiae (Aranda et al., 2004), is highly effective at stabilizing macromolecular structures that are exposed to chaotropic substances (e.g. ethanol, 2-phenylethanol) and enabling cells to survive desiccation–rehydration cycles (Crowe et al., 1984; Mansure et al., 1994). The highest reported tolerance to ethanol stress was in S. cerevisiae cells capable of growth and metabolism up to 28% v/v (≡ 20% w/v or 4.3 M; chaotropic activity = 25.3 kJ g−1; Hallsworth, 1998; Hallsworth et al., 2007) when the medium contained high concentrations of a compatible solute, proline (Thomas et al., 1993); furthermore of the seven microbes reported to have the highest resistance to other chaotropic substances (including urea, phenol) the majority are weed species including A. wentii, S. cerevisiae, Escherichia coli and P. putida (Hallsworth et al., 2007).

The stress mechanisms for numerous types of cellular stress operate at the level of water:macromolecule interactions (Crowe, et al., 1984; Brown, 1990; Sikkema et al., 1995; Casadei et al., 2002; Ferrer et al., 2003; Hallsworth et al., 2003a; 2007; McCammick et al., 2009; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2010). As front-line stress protectants, compatible solutes (within limits) can therefore mollify stress the inhibitory effects of an indefinite number of stress parameters (see Crowe, et al., 1984; Brown, 1990; Hallsworth et al., 2003b; Bhaganna et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2013) but cells also upregulate other protection systems (see also above; Table 3). In S. cerevisiae, an extensive number of genes that code for protein-stabilizing proteins, metabolic enzymes and cellular-organization proteins are regulated by a single promoter – the stress response element (STRE) – which is activated under cellular stress. This regulatory system enables the coordination of an array of stress responses in an energy-efficient manner (Table 3). Numerous studies show that the S. cerevisiae responses to osmotic stress [via the high-osmolarity glycerol-response (HOG) pathway], oxidative stress, and challenges to protein and membrane stability are exceptionally efficient (Table 3; Brown, 1990; Costa et al., 1997; Hallsworth, 1998; Rodríguez-Peña et al., 2010; Szopinska and Morsomme, 2010). In addition to these stress responses, there is evidence that the dynamics of polyphosphate and glycogen metabolism in S. cerevisiae are wired in such a way to boost ATP production (Castrol et al., 1999), and that the ploidy levels of many strains enhance tolerance towards oxidative and other stresses (Table 3). The energy-generation and energy-conservation strategies employed by S. cerevisiae have apparent parallels in other weed species; for example, analyses of synonymous codon bias in the genomes of fast-growing bacteria including E. coli and Bacillus subtilis suggest that genes associated with energy generation are highly expressed (Karlin et al., 2001; Table 5; see also above). The enhanced energy efficiency that is apparent in some weed species not only underpins their robust stress biology, but is required to sustain a vigorous growth phenotype and/or to out-grow competitors.

Table 5.

Growth, nutritional versatility and resource acquisition and storage: cellular characteristics that contribute to weed-like behaviour.a

| Metabolites, proteins, molecular characteristics, and other traits | Function(s) | Phenotypic traits | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to out-grow competitors | |||

| Multiple copies of ribosomal DNA operons | Enhanced production of ribosomes | Rapid protein synthesis | Soil bacteria able to grow rapidly on high-nutrient media have an average of ∼ 5.5 copies of ribosomal DNA operons (compared with ∼ 1.4 copies for slow-growing species; Klappenbach et al., 2000) |

| Key roles of di-/tripeptide-transport protein (dtpT) and oligopeptide transport ATP-binding protein (Opp) | Permease (dtpT) and ABC-type transporter (Opp) that enable efficient scavenging of diverse peptides (Altermann et al., 2005) | Efficient uptake of diverse peptides | These proteins enable species such as Lactobacillus acidophilus to efficiently scavenge peptides and thereby minimize the need for de novo synthesis of amino acids (Altermann et al., 2005) |

| High-efficiency DNA polymerase | Apparent correlation with short generation-time in fast-growing bacteria (Couturier and Rocha, 2006) | Rapid genome replication | The relatively fast-growing Mycobacterium smegmatis (generation time ∼ 3 h) has a DNA polymerase processing rate of 600 nucleotide s−1, compared with 50 nucleotide s−1 for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (generation time ∼ 24 h; Straus and Wu, 1980; Couturier and Rocha, 2006) |

| Overlapping replication cycles | Bacteria can initiate a new round of chromosomal DNA replication before the completion of an ongoing round of synthesis | Rapid genome replication | Escherichia coli can operate up to eight origins of replication simultaneously (see Nordström and Dasgupta, 2006) |

| Polyploidy, aneuploidy, association with plasmids, and/or hybridization that enhance(s) vigour | Multiple copies of genomic DNA can lead to increased vitality, enhanced growth rates, increased production of antimicrobials, and enhanced energy generation and stress tolerance (see also Table3) | Enhanced vigour | Shorter generation times in polyploid bacteria may arise from a number of factors including the increased number of ribosomal DNA operons (Cox, 2004; see also above) and gene localization within the genome (Pecoraro et al., 2011). A recent study of F1 hybrids produced by crossing 16 wild-type strains of S. cerevisiae showed that many F1 strains displayed hybrid vigour (Timberlake et al., 2011)b> |

| Traits for high-efficiency energy generation (see Table3) | |||

| Efficient system to eliminate free radicals (see also Table3) | Elimination of reactive oxygen species that can react with and damage macromolecular and cellular structures | Ability to cope with the oxidative stress associated with high growth rates | The enhanced rates of oxidative phosphorylation required for rapid growth result in the increased generation of free radicals; a phenomenon that has been observed in plant weeds (Wu et al., 2011). Aspergillus mutants that lack superoxide dismutase genes are unable to grow under environmental conditions that favour a high metabolic rate (Lambou et al., 2010). Strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have an auxiliary manganese-dependent version of superoxide dismutase that does not require iron and is upregulated under iron-limiting conditions (Britigan et al., 2001) |

| Nutritional and metabolic versatilityc | |||

| Genes for catabolism of a wide spectrum of hydrocarbons; e.g. those coding for the catechol-, homogentisate-, phenylacetate- and protocatechuate-catabolic pathways (cat, hmg, pha and pca gene families respectively) | Facilitate the synthesis of proteins that enable the utilization of hydrocarbons (including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) | Ability to utilize diverse hydrocarbons as a carbon and/or energy source | Such compounds can be utilized as a sole carbon source by a small number of metabolically versatile microbes such as Pantoea spp., Pseudomonas putida and Pichia anomala (Timmis, 2002; Pan et al., 2004; Vasileva-Tonkova and Gesheva, 2007) but are also known to exert cellular stress even at low concentrations (Bhaganna et al., 2010). Catabolism of hydrocarbons will therefore alleviate stress at the same time as providing for energy generation and growth (Jiménez et al., 2002; Domínguez-Cuevas et al., 2006) |

| Catabolite-repression system for energy-efficient utilization of complex substrates | Advanced system to regulate utilization of diverse substrates | Energy-efficient growth in nutritionally complex environments | A cAMP-independent catabolite-repression system has been identified in P. putida that enables the ordered assimilation of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur substrates (most energy-favourable first; Daniels et al., 2010) |

| Production and secretion of biosurfactants (e.g. rhamnolipids in Pantoea, P. aeruginosa and P. putida; glycolipoproteins in Aspergillus spp.) | Solubilization of hydrophobic molecules (and antimicrobial activity; see Table6) | Ability to enhance the bioavailability of hydrophobic substrates | In vitro studies of Pantoea and P. aeruginosa demonstrate that biosurfactants enhance the uptake of hydrophobic substrates (Al-Tahhan et al., 2000; Vasileva-Tonkova and Gesheva, 2007; Reis et al., 2011) and thereby facilitate colonization of hydrocarbon-containing habitats (see Table S1). Aspergillus species can produce copious amounts of biosurfactant (Desai and Banat, 1997; Kiran et al., 2009) |

| Diverse saprotrophic enzymes (e.g. cellulose, ligninase) able to function over a range of conditions | Extracellular degradation of polymeric organic molecules for use as a carbon and energy source | Ability to grow saprotrophically | Saprotrophic capabilities enhance the range of substrates from which nutrition can be obtained. Saprotrophic enzymes from Aspergillus species can function over a wide range of environmental stresses (Hong et al., 2001) |

| Proteins for oxidation of methane and/or methanol (e.g. alcohol oxidase in Pichia and Kodamaea) | Oxidation of one-carbon substrates that are used for energy generation/growth | Ability to utilize one-carbon substrates | One-carbon substrates are environmentally commonplace and their utilization can facilitate rapid growth (van der Klei et al., 1991; McDonald and Murrell, 1997; Pacheco et al., 2003) |

| Pathways to utilize a broad range of nitrogen substrates (e.g. D-amino acids, urea, ammonium salts, and macromolecules such as collagen and elastin) | Assimilation of nitrogen into anabolic pathways for de novo synthesis of amino acids and nucleic acids | Ability to utilize a wide spectrum of nitrogen sources | Versatility in the utilization of nitrogen substrates can enable proliferation in open habitats by, and opportunistic pathogenicity for, Aspergillus, Pseudomonas putida and other weed species (Krappmann and Braus, 2005; Daniels et al., 2010; see also Table S1). Rhodotorula spp., including metabolically versatile weed species, can grow on D-amino acids as a sole carbon and nitrogen source (Simonetta et al., 1989; Pollegioni et al., 2007) |

| Genome-mediated responses to maintain growth under low-nutrient conditions (e.g. upregulation of glutamate dehydrogenase in P. putida) | Glutamate dehydrogenase plays key roles in nitrogen assimilation and metabolism | Ability to adapt metabolism for growth at high- or low-nutrient concentrations | Expression of gdh was between 5- and 26-fold greater in P. putida cells under low-nutrient conditions compared with a high-nutrient control (Syn et al., 2004). The synthesis of glutamate via glutamate dehydrogenase, rather than glutamate synthase, consumes 20% less ATP (Syn et al., 2004) |

| Enzyme systems that enable metabolism under nutrient-limiting conditions by avoiding dependence on specific cofactors | Utilization of substitute cofactor, or replacement of enzyme system(s) that would require a cofactor that is environmentally scarce | Maintenance of essential enzyme functions at low nutrient concentrations | For example arginase in S. cerevisiae (Middelhoven et al., 1969) and phospholipase C in P. aeruginosa (Stinson and Hayden, 1979) |

| Pathways to synthesize phosphate-free membrane lipids | Maintenance of membrane functions under phosphate-limited conditions | Ability to remain active, and grow, in phosphate-depleted environments | Pseudomonas spp. can synthesize membranous glycolipids as an alternative to phospholipids under low-phosphate conditions (Minnikin et al., 1974). Salinibacter ruber and a number of phytoplankton species utilize sulfur in membrane glycolipids that have a sulfoquinovose-containing (non-phosphorus) head group and are synthesized in response to low phosphate availability (Benning, 1998; Corcelli et al., 2004; Bellinger and Van Mooy, 2012) |