Abstract

PURPOSE

Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors are effective cancer therapies, but they cause a rash in greater than 50% of patients. This study tested tetracycline for rash prevention.

METHODS

This placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial enrolled patients who were starting cancer treatment with an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor. Patients could not have had a rash at enrollment. All were randomly assigned to either tetracycline 500 milligrams orally twice a day for 28 days versus a placebo. Patients were monitored for rash (monthly physician assessment and weekly patient-reported questionnaires), quality of life (SKINDEX-16), and adverse events. Monitoring occurred during the 4-week intervention and then for an additional 4 weeks. The primary objective was to compare the incidence of rash between study arms, and 30 patients per arm provided a 90% probability of detecting a 40% difference in incidence with a p-value of 0.05 (2-sided).

RESULTS

Sixty-one evaluable patients were enrolled, and arms were well balanced on baseline characteristics, rates of drop out, and rates of discontinuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor. Rash incidence was comparable across arms. Physicians reported that 16 tetracycline-treated patients (70%) and 22 placebo-exposed patients (76%) developed a rash (p=0.61). Tetracycline appears to have lessened rash severity, although high drop out rates invite caution in interpreting findings. By week 4, physician-reported grade 2 rash occurred in 17% of tetracycline-treated patients (n=4) and in 55% of placebo-exposed patients (n=16); (p=0.04). Tetracycline-treated patients reported better scores, as per the SKINDEX-16, on certain quality of life parameters, such as skin burning or stinging, skin irritation, and being bothered by a persistence/recurrence of a skin condition. Adverse events were comparable across arms.

CONCLUSION

Tetracycline did not prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced rashes and cannot be clinically recommended for this purpose. However, preliminary observations of diminished rash severity and improved quality of life suggest this antibiotic merits further study.

Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors are emerging as effective therapies for patients with non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreas cancer, head and neck cancer and other malignancies [1,2,3,4]. These agents are well tolerated, but a rash is reported to occur in greater than 50% of treated cancer patients [1,4]. Developing on the face, trunk, and upper extremities, this rash is often acneiform in appearance, mild in severity, and quick to resolve even with ongoing cancer therapy. However, more severe (grade 3+) or more persistent rashes can also occur, particularly with the administration of epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies [4].

How are these rashes typically managed? When severe, cessation of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor is sometimes considered. The rash then usually resolves, thereby allowing uneventful reinstitution of cancer therapy [5]. This approach can be disquieting for cancer patients, especially in light of data that point to rash development as a surrogate marker for tumor response and improved survival [6]. Anecdotal reports have also described rash attenuation after the initiation of other therapies, including systemic antibiotics such as tetracycline [7,8]. The latter is commonly used for acne, and the clinical similarity of typical acne and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rash suggests that this antibiotic might play a role in preventing or treating these drug-induced rashes [9,10,11]. Additionally, tetracycline carries anti-inflammatory effects which might also help with rash palliation [12].

Despite such anecdotal reports, to our knowledge, no published placebo-controlled trial has ever examined the role of tetracycline in preventing rashes induced by epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. In view of the waxing and waning nature of these rashes and the anxiety they evoke, it is important to begin to seek rigorous evidence on the use of tetracycline for rash prevention. Thus, the North Central Cancer Treatment Group conducted this placebo controlled trial to test the role of tetracycline in rash prevention in patients starting cancer therapy with an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor.

METHODS

Overview

The North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) conducted this phase III trial. The Institutional Review Boards at each specific study site approved the study protocol prior to patient enrollment. All patients signed a consent form prior to participation.

Patient Eligibility

The following criteria were required prior to enrollment: 1) patient age >/= 18 years; 2) cancer diagnosis; 3) an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (must have been gefitinib, cetuximab, erlotinib, or one of the other investigational agents within this class of drugs) to have been initiated within 7 days of registration onto the present trial, either before or after; 4) creatinine </= 2 mg/dL and total bilirubin </= 2 mg/dL within 14 days of trial registration; 5) patient able to take oral medications reliably and able to complete questionnaires with assistance if needed. Patients were not allowed to enroll in this trial in the event of any one of the following: 1) previous allergic reaction to tetracycline or one of its derivatives; 2) use of tetracycline within 7 days of trial registration; 3) pregnant or nursing or of child-bearing potential and unwilling to employ contraception; 4) severe nausea or vomiting; 5) any rash at the time of study registration; or 6) history of a skin problem that the treating oncologist thought might “flare” during cancer therapy.

Pretreatment and follow-up evaluations

All patients underwent a history, physical exam, and assessment of performance score within 14 days of trial registration. A blood draw for a serum creatinine and total bilirubin was obtained at baseline.

Patients were monitored for rash development, quality of life, and adverse events. Patient-reported assessment included: 1) a brief rash incidence questionnaire; 2) a previously-validated SKINDEX-16 questionnaire relevant to rash development and its implications [13]; and 3) a questionnaire on patient compliance with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. These questionnaires were to be completed at baseline and weekly for 8 weeks after starting tetracycline/placebo. Of note, the validated SKINDEX-16 questionnaire provides a comprehensive patient-reported skin assessment tool that includes 16 questions on itching, burning or stinging, skin pain, skin irritation, and patient concerns and worries about a variety of other aspects of skin issues.

The patient’s treating oncologist was to perform an evaluation at the end of 4 weeks and at the end of 8 weeks. This evaluation entailed a history and physical examination, an assessment of patient performance status, and an assessment of adverse events, including gastrointestinal toxicity and rash development, as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. These criteria indicated that a rash involving < 50 of the body surface area with symptoms was grade 2, that involving >/= 50% of the body surface area with symptoms was a grade 3, and a more generalized, exfoliative rash was a grade 4. These evaluations were designed to detect rash development during the one-month tetracycline/placebo treatment as well as the possible development of a rebound rash between weeks 5–8 after tetracycline/placebo was stopped. It should be noted that the protocol included a picture of a patient with an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor induced rash.

Treatment

Prior to randomization, patients were stratified according to the following: 1) first-line cancer therapy versus other; 2) type of epidermal growth factor inhibitor: gefitinib versus cetuximab versus other; 3) corticosteroid use: yes versus no. Thereafter, patients were randomly assigned to receive tetracycline 500 mg orally twice a day for 4 weeks versus an identical placebo at the same frequency. Because the primary endpoint of this study was rash prevention, it was thought appropriate to continue tetracycline for 4 weeks. The tetracycline/placebo intervention was to start within seven days of trial enrollment. Dosing was based on previous favorable results for treating typical acne as well as anecdotal reports for treating epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced rashes with this antibiotic [10].

The protocol specified that patients were to stop the tetracycline/placebo in the event of grade 2 or worse nausea and/or vomiting. The latter was characterized by 2–5 episodes in 24 hours. Any other adverse events attributable to the tetracycline/placebo were to prompt the treating oncologist to utilize his/her judgment as to whether to stop the tetracycline/placebo.

The protocol also clearly stated that all other supportive care measures were allowed. The protocol did not dictate any aspect of cancer therapy. Patients were allowed to take antacids but were instructed not to take them within two hours of taking the tetracycline/placebo.

Statistical Analyses

The primary objective of this trial was to compare the incidence of rash between tetracycline-treated and placebo-exposed patients. A sample size of 30 patients per group provided a 90% probability of detecting a difference in rash incidence of 40% between the two study arms and of thereby rejecting the null hypothesis of equal proportions with a p-value of 0.05 as a 2-sided test. Justification for seeking this large effect size rests upon the study team’s clinical judgment that the inconvenience of taking an antibiotic twice daily over one month necessitated a sizable improvement in rash incidence as a trade-off. Physician-reported and patient-reported incidence was analyzed separately, and a Fisher’s Exact test was used to compare rates between study arms. Other endpoints relevant to rash development included comparisons of rash severity between study arms. Averaged, maximal rash severity for each patient was also compared by means of a Kruskal-Wallis test. Analyses were performed with data gathered by the 4-week time-point, but in the event of a rebound rash effect after stopping the tetracycline, a similar analysis was performed by 8 weeks.

Secondary endpoints included comparisons across study arms to assess changes in quality of life scores from baseline, as measured by the SKINDEX-16 questionnaire. The incidence of adverse events was compared across arms with a Fisher’s Exact test. Separate analyses at the 4-week and 8-week time points were undertaken for the reasons alluded to above.

RESULTS

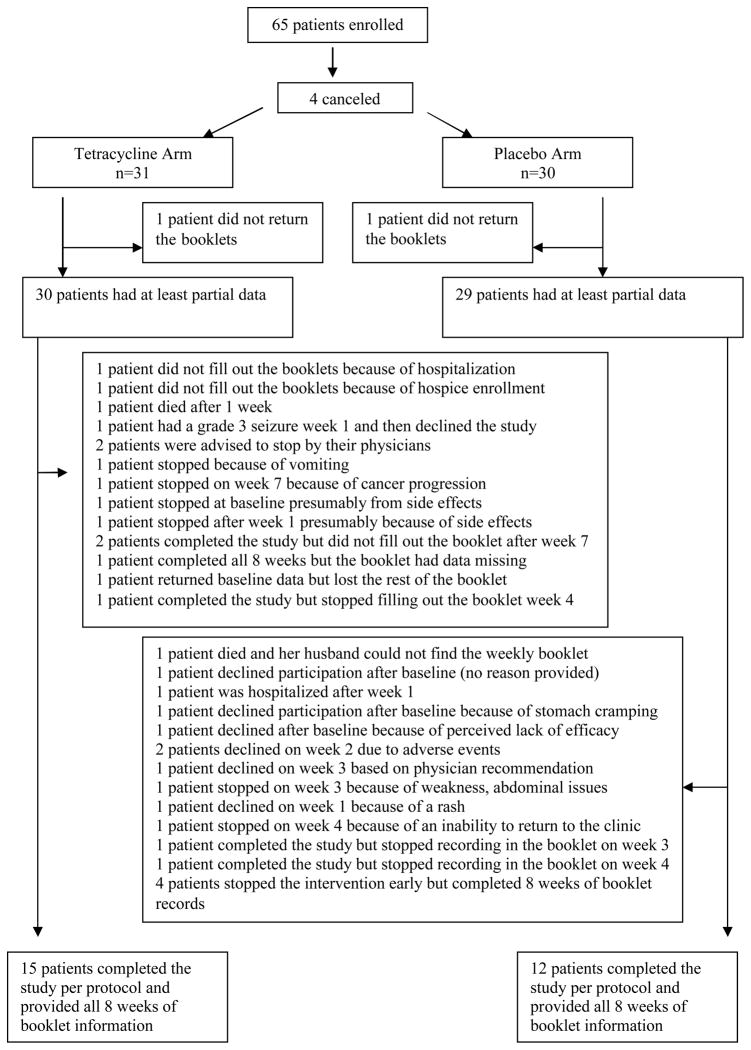

Between February of 2005 and July of 2005, the target accrual of 65 was met, and each patient was randomly assigned to the appropriate study arm. Subsequently, 4 received no study treatment, leaving 61 evaluable patients (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the study group are listed in Table 1. The median age of the tetracycline-treated group was 71 years (range 40, 84 years) and of the placebo-exposed group 63 years (range 49, 84 years). Within the entire cohort, 38% were women. The two study arms were balanced with respect to whether patients were receiving first-line cancer therapy or not, type of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor prescribed, cancer type, and whether cancer therapy was being given with curative intent or not. Of note, a slightly larger percentage of patients were receiving cetuximab, an antibody to the epidermal growth factor receptor, as opposed to gefitinib, a small molecule inhibitor.

Figure 1. Consort Diagram.

The study arms appeared well balanced for drop outs and other such factors throughout the conduct of the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics*

| TETRACYCLINE ARM (n=31) | PLACEBO ARM (n=30) | P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| AGE | |||

| Median in years (range) | 71 (40, 84) | 63 (49, 84) | 0.14 |

|

| |||

| GENDER | |||

| Female | 16 (52) | 7 (23) | 0.02 |

| Male | 15 (48) | 23 (76) | |

|

| |||

| FIRST-LINE CHEMOTHERAPY? | |||

| Yes | 11 (35) | 11 (37) | 0.92 |

| No | 20 (65) | 19 (63) | |

|

| |||

| EPIDERMAL GROWTH FACTOR RECEPTOR INHIBITOR | |||

| Gefitinib | 3 (10) | 5 (17) | 0.60 |

| Cetuximab | 11 (35) | 12 (40) | |

| Other | 17 (55) | 13 (43) | |

|

| |||

| CORTICOSTEROID THERAPY? | |||

| Yes | 6 (20) | 6 (20) | 0.94 |

| No | 25 (80) | 25 (80) | |

|

| |||

| CANCER TYPE | |||

| Lung | 18(58) | 13 (43) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (23) | 9 (30) | 0.52 |

| Other | 6 (19) | 8 (27) | |

|

| |||

| POTENTIALLY CURABLE MALIGNANCY? | |||

| Yes | 3 (10) | 3 (10) | 0.97 |

| No | 28 (90) | 27 (90) | |

Numbers in parentheses denote percentages unless otherwise noted.

The time on study was comparable between study arms. The median time on study for patients on the tetracycline arm was 28 days (range: 3–82 days) and on the placebo arm 27 days (range 4–48 days); (p=0.18). A few patients continued on therapy beyond the one-month treatment and one-month monitoring periods because of breaks in treatment. Reasons for stopping among tetracycline-treated and placebo-exposed patients included completion of study treatment in 62% and 48% of patients, respectively; patients’ reluctance to receive further study treatment in 7% and 21%, respectively; development of an adverse event that necessitated stopping study participation in 14% and 14%, respectively; patient death in 3% and 3%, respectively; and other miscellaneous or unknown reasons in the remaining patients.

Compliance with the epidermal growth factor inhibitor was assessed, as it was acknowledged that stopping the epidermal growth factor receptor would also lead to rash prevention or resolution. Six patients, three on each study arm, stopped taking the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor within the first month. One tetracycline-treated patient stopped taking the epidermal growth factor receptor because of rash development, and two placebo-exposed patients stopped for the same reason.

The incidence of rash was comparable across study arms (Table 2). During the first 4 weeks, physicians reported that 16 tetracycline-treated patients (70%) developed a rash and 22 placebo-exposed patients (76%) also did (p=0.61). Between 5 to 8 weeks, when patients were no longer taking the antibiotic/placebo, physicians reported that 13 tetracycline-treated patients (87%) and 16 patients placebo-exposed patients (84%) had a rash (p=0.84). Patient-reported rates of rash development were similar. During the first 4 weeks, 15 tetracycline-treated patients (80%) reported a rash, as did 15 placebo-exposed patients (68%); (p=0.35). Between weeks 5 to 8, when patients were no longer taking the antibiotic/placebo, 14 tetracycline-treated patients (70%) reported a rash, whereas 15 placebo-exposed patients also had a rash (94%); (p=0.07). Although one might argue in favor of a late trend in tetracycline-treated patients, the small remaining sample size coupled with a lack of statistically significant differences between groups indicate that tetracycline did not impact this study’s primary endpoint of rash incidence.

Table 2.

Rash Incidence and Severity

| TIMEPOINT (RASH EXTENT) | Patients with a Rash (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician-Reported | Patient-Reported | |||||

| TETRACYCLINE ARM | PLACEBO ARM | P-Value | TETRACYCLINE ARM | PLACEBO ARM | P-Value | |

| 4 WEEKS (ANY) | 16 (70) | 22 (76) | 0.61 | 15 (68) | 20 (80) | 0.35 |

| 4 WEEKS (GRADE 2 or >50% SURFACE AREA) | 4 (17) | 16 (55) | 0.009 | 0 | 1 (4) | 0.45 |

| 8 WEEKS (ANY) | 13 (87) | 16 (84) | 0.84 | 14 (70) | 15 (93) | 0.07 |

| 8 weeks (GRADE 2 or >50% SURFACE AREA) | 4 (27) | 9 (47) | 0.3 | 0 | 3 (19) | 0.04 |

With regard to rash severity, a few indicators suggest that tetracycline may have carried a favorable influence (Table 2). By week 4, physician-reported grade 2 rash occurred in 17% of tetracycline-treated patients (n=4) and in 55% of placebo-exposed patients (n=16); (p=0.04). By week 8, however, when 44% of the cohort had dropped out, physician-reported grade 2 rash occurred in 20% of tetracycline-treated patients and in 47% of placebo-exposed patients; (p=0.5). Of note, the worst physician-reported rash was grade 3 and occurred in only one patient who was on the tetracycline arm.

In addition, patient-reported rash severity also suggested slightly better outcomes among tetracycline-treated patients, although a diminishing sample size invites caution in result interpretation. There was no difference in patient-reported extent of rash during weeks 1–4. However, during weeks 5–8, the few remaining patients described differing rates of rash covering 51–75% of their body: no tetracycline-treated patient had a rash to this extent in contrast to 3 placebo-exposed patients (19%); (p=0.04).

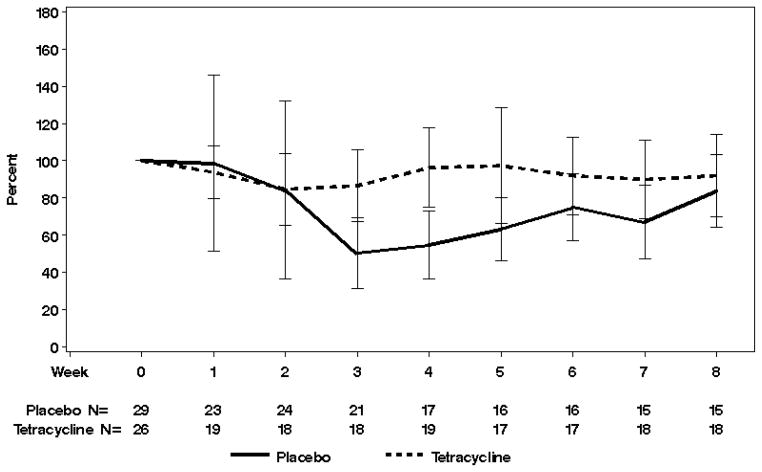

The SKINDEX-16 questionnaire did not show uniform, statistically significant differences across treatment arms -- with a few notable exceptions. Serial answers to the question, “During the past week, how often have you been bothered by your skin itching?” revealed that the median percent of baseline at week 4 was 83% and 50% in tetracycline-treated and placebo-exposed patients, respectively (p=0.005). Of note, the higher median percent is more favorable (Figure 2). Similar, statistically significant differences between arms in change in scores from baseline to 4 weeks were observed in questions that asked about skin burning or stinging, skin irritation, and being bothered by a persistence/recurrence of the skin condition. Again, these findings favored the tetracycline arm. In contrast, serial answers to the question, “During the past week, how often have you been bothered by being annoyed about your skin?” revealed that tetracycline-treated patients faired poorly by the end of the study. The median percent of baseline still present at week 8 was 67% in tetracycline-treated patients and 100% in placebo-exposed patients (p=0.04), again, with a lower median percent being less favorable. In short, the SKINDEX-16 suggested that tetracycline exerted positive effects on quality of life in 4 questions, a negative effect in one question, and no statistically significant effects in the other 11 questions.

Figure 2. SKINDEX-16 Itching Scores.

Serial SKINDEX-16 scores showed a few favorable effects with tetracycline, including better itching scores by week 4. In this figure the y-axis helps illustrate the percentage change in scores from baseline, and the x-axis shows time and the number of patients being evaluated at each time point. The median percent of baseline present at week 4 was 83% in tetracycline-treated patients and 50% in placebo-exposed patients with the higher median percent being more favorable (p=0.005).

Finally, as expected, the tetracycline was well tolerated. There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two study arms. (See Table 3.)

Table 3.

Select Adverse Events with Grade*

| ADVERSE EVENTS | Tetracycline Arm ** (N=27) | Placebo Arm** (N=29) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Anorexia | 0.48 | ||

| 0 | 26 (96) | 29 (100) | |

| 2 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Constipation | 0.49 | ||

| 0 | 27 (100) | 27 (93) | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 (7) | |

|

| |||

| Dyspepsia | 0.99 | ||

| 0 | 26 (96) | 28 (97) | |

| 2 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (3) | |

|

| |||

| Fatigue | 0.29 | ||

| 0 | 24 (89) | 28 (97) | |

| 2 | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| 3 | 1 (4) | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Nausea | 0.91 | ||

| 0 | 16 (59) | 18 (62) | |

| 1 | 7 (26) | 7 (24) | |

| 2 | 4 (15) | 3 (10) | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (3) | |

|

| |||

| Abdominal Pain | 0.35 | ||

| 0 | 22 (81) | 20 (69) | |

| 1 | 3 (11) | 7 (24) | |

| 2 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| 3 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

|

| |||

| Vomiting | 0.5 | ||

| 0 | 19 (70) | 23 (79) | |

| 1 | 4 (15) | 3 (10) | |

| 2 | 4 (15) | 2 (7) | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (3) | |

As per the Common Terminology Criteria (version 3).

Numbers in parentheses denote percentages.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to move beyond anecdotal reports on how to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rashes and to seek rigorous justification for prescribing tetracycline in this setting. Designed as a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, this study sought as its primary endpoint to determine whether tetracycline lowers rash incidence. As prescribed here, tetracycline did not decrease the incidence of rash compared to placebo. Therefore, prescribing this antibiotic to prevent an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced rash cannot be clinically recommended based on these data.

Despite these negative findings, however, this study did generate some highly provocative, albeit preliminary, findings. This study detected a decrease in incidence of slightly more severe (grade 2) rashes in patients assigned to the tetracycline arm. In addition, tetracycline-treated patients reported other favorable effects, recounting less itching, less burning and stinging, and less skin irritation compared to placebo-exposed patients. Are these data strong enough to justify prescribing tetracycline to all patients at risk for a highly bothersome rash or to patients who have already developed such a rash? Although this study does not provide the final answer to this fundamental question, a few advisory remarks may be in order. In view of the preliminary benefits in lessening rash severity, the clinical acceptance of tetracycline in rash treatment, the favorable toxicity profile of tetracycline, and the current lack of clinical data to dictate otherwise, it appears that prescribing this antibiotic to patients who have developed a severe rash remains appropriate until further clinical data become available. However, we believe it is also important to move forward with clinical trials to determine definitively whether tetracycline is truly indicated for rash treatment.

In view of the above, it is important to discuss one other aspect of this study. Since the initiation of this trial, the clinical landscape of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors has changed. Cetuximab, an antibody to the epidermal growth factor receptor, was approved after this trial had opened. Then, after accrual was completed, panitumumab was approved for clinical use. These agents’ notable tendency to induce rashes might not have been fully captured in the present study, in which only 35–40% of patients were receiving antibody therapy. Although rash occurred in over 70% of patients in this study, the present-day incidence rate of rash in clinical practice may in fact be higher with the greater availability of antibody therapy. Thus, there is a compelling need to continue to conduct research on how best to prevent and palliate rashes that occur from these agents.

Finally, a major strength of this study centers on its utilization of a quality of life assessment. To date, few studies have sought to understand the implications of epidermal growth factor receptor-induced skin rashes from the patient’s vantage point. By means of the SKINDEX-16, this trial showed that these rashes bother patients -- they must contend with itching, burning, and other types of skin irritation. These troublesome, symptoms also provide a strong impetus for further research on the palliation of this drug-induced rash.

Footnotes

This study was conducted as a collaborative trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic and was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-35195, CA-35090, CA-35113, CA-35103, CA-35415, CA-35431, CA-35103, CA-35269, CA-35101, CA-37417, CA-63848, CA-63849, and CA-35267.

Additional participating institutions include: Iowa Oncology Research Association CCOP, Des Moines, IA 50309-1014 (Roscoe F. Morton, M.D.); Meritcare Hospital CCOP, Fargo, ND 58122 (Preston D. Steen, M.D.); Michigan Cancer Research Consortium, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 (Philip J. Stella, M.D.); Missouri Valley Cancer Consortium, Omaha, NE 68106 (Gamini S. Soori, M.D.); Medcenter One Health Systems, Bismarck, ND 58506 (Edward J. Wos, M.D.); Rapid City Regional Oncology Group, Rapid City, SD 57709 (Richard C. Tenglin, M.D.); Metro-Minnesota Community Clinical Oncology Program, St. Louis Park, MN 55416 (Patrick J. Flynn, M.D.); Montana Cancer Consortium, Billings, MT 59101 (Benjamin T. Marchello, M.D.)

References

- 1.Shepherd FA, Rodriques Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJ, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1201–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochster HS, Haller DG, de Gramont A, et al. Consensus report of the international society of gastrointestinal oncology on therapeutic progress in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:676–685. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patiyil S, Chan SN, Jatoi A. New agents, new rashes: an update on skin complications from cancer chemotherapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006;8:269–274. doi: 10.1007/s11912-006-0032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang PA, Tsao MS, Moore MJ. A review of erlotinib and its clinical use. Exper Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:177–193. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janne PA, Gurubhagavatula S, Yeap BY, et al. Outcomes of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib on an expanded access study. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsythe B, Faulkner K. Overview of the tolerability of gefitinib monotherapy: clinical experience in non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Saf. 2004;27:1081–1092. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane P, Williamson DM. Treatment of acne vulgaris with tetracycline hydrochloride: a double blind trial with 51 patients. Br Med J. 1969;649:76–79. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5649.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gammon WR, Meyer C, Lantis S, et al. Comparative efficacy of oral erythromycin versus oral tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a double blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meynadier J, Alirezai M. Systemic antibiotics for acne. Dermatology. 1998;196:135–139. doi: 10.1159/000017847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rempe S, Hayden JM, Robbins RA, Hoyt JC. Tetracyclines and pulmonary inflammation. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:232–236. doi: 10.2174/187153007782794344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality of life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]