Abstract

The microstructure and nonohmic properties of SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO varistor system doped with different amounts of ZrO2 (0–2.0 mol%) were investigated. The proposed samples were sintered at 1400°C for 2 h with conventional ceramic processing method. By X-ray diffraction, SnO2 cassiterite phase was found in all the samples, and no extra phases were identified in the detection limit. The doping of ZrO2 would degrade the densification of the varistor ceramics but inhibit the growth of SnO2 grains. In the designed range, varistors with 1.0 mol% ZrO2 presented the maximum nonlinear exponent of 15.9 and lowest leakage current of 110 μA/cm2, but the varistor voltage increased monotonously with the doping amount of ZrO2.

1. Introduction

SnO2 varistors are semiconducting ceramic devices, which possess nonlinear voltage-current characteristics due to their grain boundary effects formed commonly by sintering SnO2 powder with minor additives (impurity). Due to their excellent energy handling capabilities, they can be applied extensively to protect electronic circuits, various semiconductor devices, and electric power systems from dangerous abnormal transient overload [1, 2].

The first impurity-doped SnO2 varistor was reported by Glot and Zlobin [3], and Pianaro et al. also made great contributions to the knowledge of varistor behavior of impurity-doped SnO2 ceramics [4]. Through a series of studies on SnO2-based varistors for decades, it is well known that an excellent SnO2 varistor system consists of three kinds of dopants: resistance reducers (varistor forming oxide, VFO), densifiers, and modifiers, respectively [5]. To date, the commonly applied VFOs are Nb5+ [6–8] or Ta5+ [9–11], which possesses high chemical valence and is soluble in SnO2 grains to decrease the grain resistivity; the densifier is insoluble ion of low chemical valence that will segregate at SnO2 grain boundary regions to promote the densification by producing oxygen vacancies, for example, Co2+ [4, 6, 7, 9, 11], Mn2+ [12, 13], and Zn2+ [8, 14], and the modifiers can effectively improve the electrical properties of the varistors, such as Cr3+, Fe3+, Cu2+, and rare earth elements [6–9, 15, 16].

Moreover, during modern ceramics processing, high energy attrition milling and ZrO2 grinding media were often applied. As a result, Zr4+ contamination in ceramic samples is a common phenomenon. However, up to now, no literature about the role of Zr4+ ion (ZrO2) in SnO2-based varistors has been reported.

Recently, we optimized a SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO varistor system, which presents varistors of good nonlinear properties but very low varistor voltage [17]. Based on it, in the present study, SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based varistor system was doped with ZrO2 (0–2.0 mol%), and the effect of ZrO2 doping on the microstructure and nonohmic properties of SnO2-Ta2O5 based varistors was investigated. To our surprise, varistors with fully dense structure and high breakdown voltage could be obtained.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

The samples were prepared using a conventional ceramic processing method with a nominal composition of (99.45-x) mol% SnO2 + 0.05 mol% Ta2O5 + 0.5 mol% ZnO + x mol% ZrO2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0). All the oxides were raw powders of analytical grade. At beginning, the raw powders were mixed in deionized water and ball-milled in polyethylene bottle for 24 h with 0.5 wt% of PVA as binder and highly wear-resistant ZrO2 balls as grinding media. Subsequently, the obtained slurries were dried at 110°C in an open oven. After drying, the powder chunks were crushed into fine powders, sieved, and pressed into pellets of 6 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm in thickness under a pressure of 40 MPa. Then, the pressed pellets were sintered at 1400°C for 2 h in a Muffle oven by heating at a rate of 300°C/h and cooling naturally. To measure the electrical properties, silver electrodes were prepared on both surfaces of the sintered disks by heat treatment at 500°C for half an hour.

2.2. Materials Characterization

The density of the samples was measured by Archimedes method according to international standard (ISO18754). Their crystalline phases were identified by X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D/max2550HB+/PC, Cu Kα, and λ = 1.5418 Å) through a continuous scan mode with speed of 8°/min. The microstructure was examined on the fresh fracture surfaces of the samples via a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Tescan XM5136). And the average size of SnO2 grains in the samples was determined using linear intercept method from the SEM images.

A high-voltage source measurement unit (Model: CJ1001) was used to record the characteristics of the applied electrical field versus current density (E-J) of the samples. The varistor voltage (V B) was determined at 1 mA/cm2 and the leakage current (I L) was the current density at 0.75V B. Then, the nonlinear coefficient (α) was obtained by the following equation:

| (1) |

where E 1 and E 2 are the electric fields corresponding to J 1 = 1 mA/cm2 and J 2 = 10 mA/cm2, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composition and Microstructure

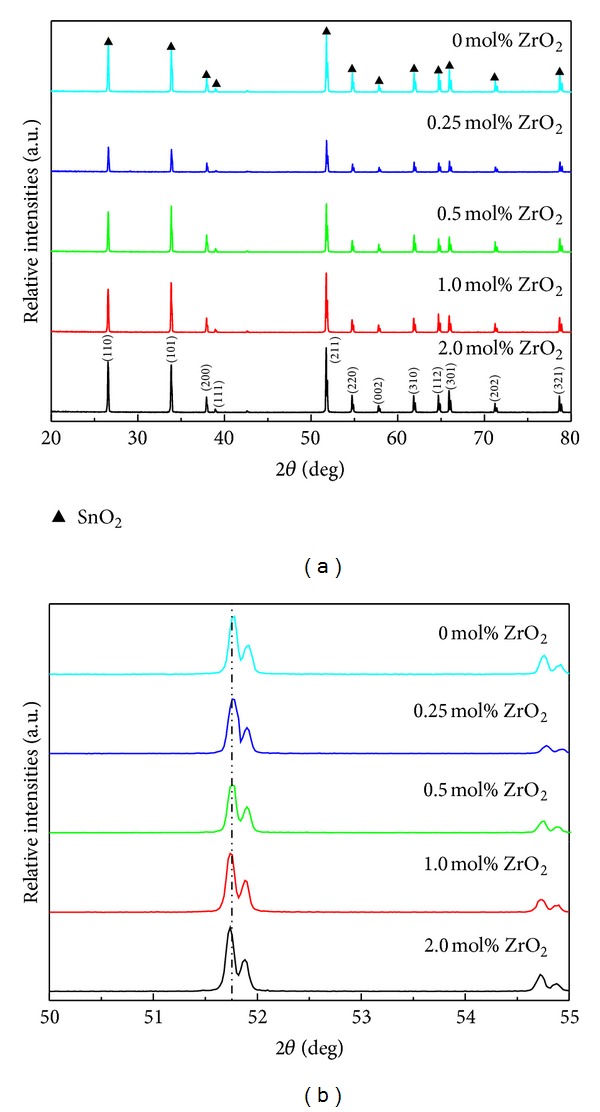

Figure 1 illustrates the XRD patterns of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based varistor ceramics doped with different amounts of ZrO2. All the sharp diffraction peaks were assigned, corresponding to the (110), (101), (200), (111), (211), (220), (002), (310), (112), (301), (202), and (321) reflections of SnO2 cassiterite phase (JCPDS card no. 77-0451). No extra phases were identified, possibly because the doping levels of the additives were too low to be detected in XRD limits. And, because of the same ionic valence and almost no radius difference between Sn4+ (0.071 nm) and Zr4+ (0.072 nm) ions, the doped ZrO2 is fully soluble in SnO2 lattice, which can be seen from almost the same positions of XRD diffraction peaks of the prepared samples as shown in Figure 1(b) in a close view to the patterns in 2θ from 50 to 55°. As for the splitting of the XRD peaks in the figure, it might be due to the peak doublet of K-alpha 1 and K-alpha 2.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based varistor ceramics doped with different amounts of ZrO2: (a) five of the samples and (b) magnified view in 2θ region of 50–55°.

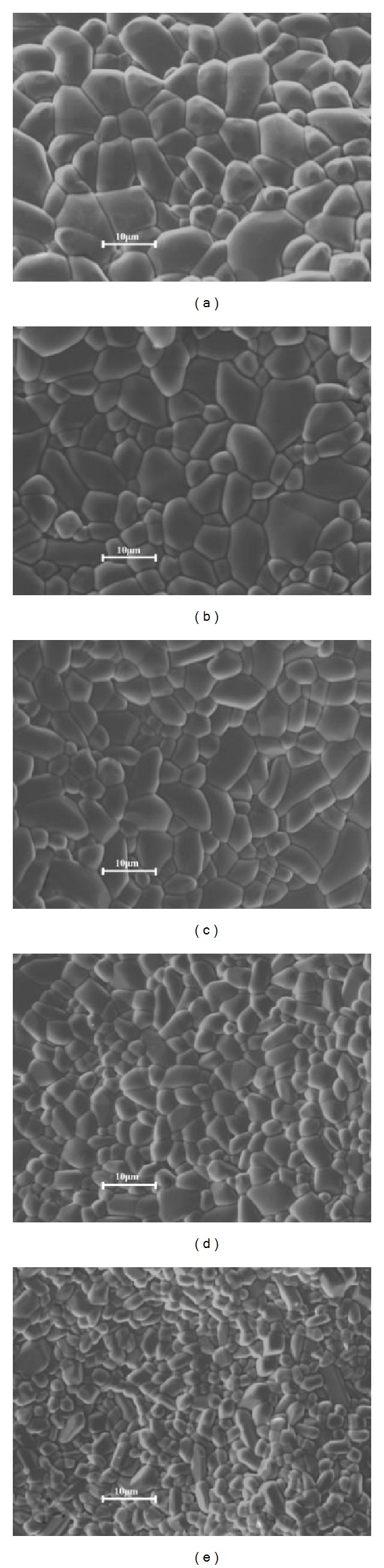

SEM images of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO based varistor ceramics also confirmed the solubility of ZrO2 into SnO2 lattice (please see Figure 2). The images reveal that, although doped with different amounts of ZrO2, the typical microstructure of the samples almost has no change: almost fully dense structure of SnO2 grains without any obvious second phases. The detailed microstructural parameters are also summarized in Table 1. With increasing doping amount of ZrO2, the density of samples decreases in a very narrow range from 6.93 to 6.80 g/cm3 partly because the density of ZrO2 (5.89 g/cm3) is lower than that of the matrix SnO2 (6.95 g/cm3), but the relative density of the samples also decreases although also in a very narrow range from 99.8% to 98.2%, which indicates a decreased sample densification and could be attributed to the lower diffusion ability of solid ZrO2 particles in SnO2 matrix at the designed sintering temperature because the melting point of ZrO2 (2680°C) is much higher than that of SnO2 (1630°C). Moreover, from these SEM images, it can be clearly seen that, with increasing ZrO2 contents in the ceramics, the average size of SnO2 grains decreases, which might be owing to the inhibited transportation of SnO2 during sintering by the doped ZrO2 with lower diffusion ability.

Figure 2.

Typical SEM images on fracture surfaces of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based varistor ceramics doped with different amounts of ZrO2: (a) undoped, (b) 0.25, (c) 0.5, (d) 1.0, and (e) 2.0 mol%.

Table 1.

Basic physical parameters of SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO varistor ceramics doped with different contents of ZrO2.

| Doping amount of ZrO2 (mol) |

Apparent density (g/cm3) |

Relative density (%) |

SnO2 grain size (μm) |

α | V B (V/mm) | I L (μA/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.93 | 99.8 | 7.87 | 4.6 | 81 | 660 |

| 0.25 | 6.89 | 99.2 | 6.67 | 6.0 | 103 | 560 |

| 0.5 | 6.88 | 99.1 | 5.45 | 8.2 | 250 | 220 |

| 1.0 | 6.84 | 98.6 | 4.55 | 15.9 | 500 | 110 |

| 2.0 | 6.80 | 98.2 | 3.03 | 11.6 | 720 | 170 |

3.2. Electrical Properties

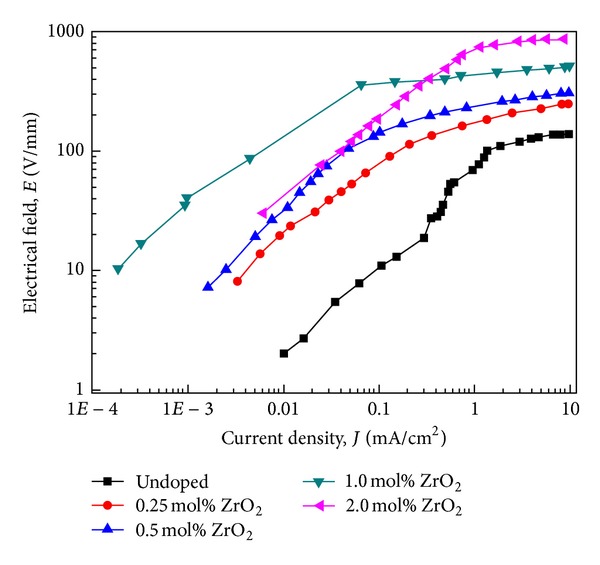

The E-J characteristics of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based ceramic varistors doped with different contents of ZrO2 are illustrated in Figure 3, and their corresponding detailed electrical parameters calculated from the E-J curves are listed in Table 1.

Figure 3.

E-J characteristic curves on a log scale at room temperature of the as-prepared SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based varistors doped with different contents of ZrO2.

The results indicate that, with increasing doping content of ZrO2 up to 1.0 mol%, the nonlinear coefficient of the samples increased up to 15.9, possibly owing to the increased carrier concentration in the varistors, decreased electrical resistivity of SnO2 grains and thus enhanced barrier height by doping, and higher number of voltage barriers due to the decrease in grain size, but it would drop down with more ZrO2 doped, due to the corresponding less dense sample structure, degraded effective grain boundary, destroyed depletion layer structure, and thus decreased barrier height. The leakage current of the samples presented an opposite trend to that of nonlinear coefficient with ZrO2 doping, and the varistors with 1 mol% ZrO2 presented the lowest leakage current, 110 μA/cm2, which is completely consistent with classic theory on their relationship [18]. Thus, it can be concluded that the optimum doping amount of ZrO2 in the proposed SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO-based ceramic varistor system was 1 mol%. The varistor voltage of the samples increased monotonously with the doping amount of ZrO2, which could be mainly attributed to the decreased SnO2 grain size, thus increasing the number of grain boundary in unit thickness after doping.

4. Conclusions

SnO2-Ta2O5-ZnO varistors doped with different amounts of ZrO2 (0–2.0 mol%) were prepared by sintering at 1400°C for 2 h with conventional ceramic processing method. The doping of ZrO2 would degrade the densification of the varistor ceramics, but inhibit the growth of SnO2 grains. In the designed range, varistors with 1.0 mol% ZrO2 presented the maximum nonlinear exponent of 15.9 and lowest leakage current of 110 μA/cm2; but the varistor voltage increased monotonously with the doping amount of ZrO2.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support for this work from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 61274015, 11274052 and 51172030), and the Transfer and Industrialization Project of Sci-Tech Achievement (Cooperation Project between University and Factory) from Beijing Municipal Commission of Education.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Bueno PR, Varela JA, Longo E. SnO2, ZnO and related polycrystalline compound semiconductors: an overview and review on the voltage-dependent resistance (non-ohmic) feature. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2008;28(3):505–529. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite DR, Cilense M, Orlandi MO, Bueno PR, Longo E, Varela JA. The effect of TiO2 on the microstructural and electrical properties of low voltage varistor based on (Sn,Ti)O2 ceramics. Physica Status Solidi A. 2010;207(2):457–461. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glot AB, Zlobin AP. Non-ohmic conductivity of tin dioxide ceramics. Inorganic Materials. 1989;25:274–276. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pianaro SA, Bueno PR, Longo E, Verala JA. A new SnO2-based varistor system. Journal of Materials Science Letters. 1995;14(10):692–694. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safaee I, Bahrevar MA, Shahraki MM, Baghshahi S, Ahmadi K. Microstructural characteristics and grain growth kinetics of Pr6O11 Doped SnO2-based varistors. Solid State Ionics. 2011;189(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JF, Su WB, Chen HC, Wang WX, Zang GZ. (Pr, Co, Nb)-doped SnO2 varistor ceramics . Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2005;88(2):331–334. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parra R, Maniette Y, Varela JA, Castro MS. The influence of yttrium on a typical SnO2 varistor system: microstructural and electrical features. Materials Chemistry and Physics. 2005;94(2-3):347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parra R, Varela JA, Aldao CM, Castro MS. Electrical and microstructural properties of (Zn, Nb, Fe)-doped SnO2 varistor systems. Ceramics International. 2005;31(5):737–742. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J-F, Chen H-C, Su W-B, Zang G-Z, Wang B, Gao R-W. Effects of Sr on the microstructure and electrical properties of (Co, Ta)-doped SnO2 varistors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2006;413(1-2):35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C-M, Wang J-F, Su W-B, Chen H-C, Zang G-Z, Qi P. Microstructure development and nonlinear electrical characteristics of the SnO2·CuO·Ta2O5 based varistors. Journal of Materials Science. 2005;40(24):6459–6462. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zang G, Wang JF, Chen HC, et al. Effects of Sc2O3 on the microstructure and varistor properties of (Co, Ta)-doped SnO2 . Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2004;377(1-2):82–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CP, Wang JF, Su WB, Chen HC, Zhong WL, Zhang PL. Effect of Mn2+ on the electrical nonlinearity of (Ni, Nb)-doped SnO2 varistors. Ceramics International. 2001;27(6):655–659. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan JW, Zhao HJ, Xi YJ, Mu YC, Tang F, Freer R. Characterisation of SnO2-CoO-MnO-Nb2O5 ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2010;30(2):545–548. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filho FM, Simões AZ, Ries A, Perazolli L, Longo E, Varela JA. Nonlinear electrical behaviour of the Cr2O3, ZnO, CoO and Ta2O5-doped SnO2 varistors. Ceramics International. 2006;32(3):283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastami H, Taheri-Nassaj E, Smet PF, Korthout K, Poelman D. (Co, Nb, Sm)-doped tin dioxide varistor ceramics sintered using nanopowders prepared by coprecipitation method. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2011;94(10):3249–3255. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaponov AV, Glot AB. Electrical properties of SnO2 based varistor ceramics with CuO addition. Journal of Materials Science. 2010;21(4):331–337. [Google Scholar]

- 17.He JF, Peng ZJ, Fu ZQ, Wang CB, Fu XL. Effect of ZnO doping on microstructural and electrical properties of SnO2-Ta2O5 based varistors. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2012;528:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang F, Peng ZJ, Zang YX, Fu XL. Progress on rare-earth doped ZnO-based varistor materials. Journal of Advanced Ceramics. 2013;2(3):201–212. [Google Scholar]