Abstract

Couplings of gemcitabine with the functionalized carboxylic acids (C9-C13) or reactions of 4-N-tosylgemcitabine with the corresponding alkyl amines afforded 4-N-alkanoyl and 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine derivatives. The analogues with a terminal hydroxyl group on the alkyl chain were efficiently fluorinated under conditions that are compatible with protocols for 18F labeling. The 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabines showed potent cytostatic activities in the low nM range against a panel of tumor cell lines while cytotoxicity of the 4-N-alkylgemcitabines were in the low μM range. The cytotoxicity for the 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine analogues were reduced approximately by two orders of magnitude in the 2′-deoxycytidine kinase (dCK)-deficient CEM/dCK- cell line whereas cytotoxicity of the 4-N-alkylgemcitabines were only 2-5 times lower. None of the compounds acted as efficient substrates for cytosolic dCK, and therefore, the 4-N-alkanoyl analogues need to be converted first to gemcitabine to display a significant cytostatic potential, while 4-N-alkyl derivatives attain the modest activity without “measurable” conversion to gemcitabine.

Introduction

Gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine, dFdC) is a chemotherapeutic nucleoside analogue used in the treatment of solid tumors in various cancers.1,2 Synthesized first in 1988 by Hertel et al.,3 gemcitabine represents first-line therapy for pancreatic and non-small cell lung cancers.4-6 Gemcitabine is hydrophilic by nature and cellular uptake is primarily facilitated by human equilibrative nucleoside transport protein 1 (hENT1).7 Gemcitabine is activated via phosphorylation to its 5′-monophosphate (dFdCMP) by deoxycytidine kinase (dCK).8,9 The dFdCMP then undergoes subsequent phosphorylation by intracellular kinases to the diphosphate (dFdCDP) and triphosphate (dFdCTP) forms.10,11 The dFdCTP can incorporate into DNA and inhibit DNA polymerases by chain termination during DNA replication and repair processes, invariably triggering apoptosis.10-12 It can also participate in “self potentiation” by inhibiting CTP synthetase and depleting CTP pools available to compete with dFdCTP for incorporation into RNA.12,13 Moreover, dFdCD(T)P inhibits both R1 and R2 subunits of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR),14-20 depleting the deoxyribonucleotide pool available to compete with dFdCTP for incorporation into DNA.15,16 Gemcitabine is therapeutically restricted by high toxicity to normal cells and rapid intracellular deamination into inactive 2′,2′-difluorouridine (dFdU) by cytidine deaminase (CDA).21

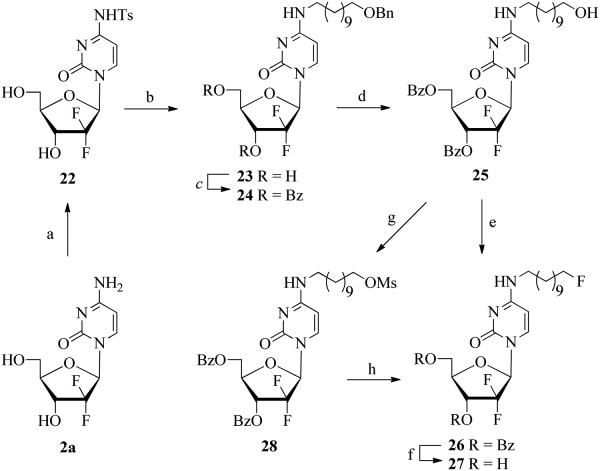

Since clinical studies have indicated that prolonged infusion times with lower doses of gemcitabine can be effective while reducing toxicity to normal cells,22,23 various prodrug strategies have been developed featuring acyl modifications on either the exocyclic 4-N-amine or 5′-hydroxyl group.24 The hydrolyzable amide modifications facilitate a slow release of gemcitabine, increasing its bioavailability and uptake while also providing resistance to enzymatic deamination.25-32 In 2004, Immordono et al. reported the increased anticancer activity of 4-N-stearoyl gemcitabine which was stable in plasma and showed an improved resistance to deamination.28 Couvreur and Cattel developed the 4-N-squalenoyl gemcitabine prodrug (SQgem) as a chemotherapeutic nanoassembly that accumulates in the cell membranes prior to releasing gemcitabine26 (Figure 1). The SQgem overcomes the low efficacy of gemcitabine in chemoresistant pancreatic cell lines and is currently undergoing preclinical development.31 The orally active 4-N-valproylgemcitabine prodrug 1 (LY2334737) currently undergoing Phase I clinical trials,30,32 was designed to be resistant to deamination by hydrolysis in acidic conditions similar to those found in the human digestive system25,29 while systematically releasing gemcitabine upon action by carboxylesterase 2. Recently, the gemcitabine prodrug with Hoechst conjugate attached to the 4-amino group targeting extracellular DNA has been reported with low toxicity but high tumor efficacy.27 Also, the lipophilic gemcitabine pro-drug CP-4126 with the 5′-OH group esterified with an elaidic fatty acid has shown antitumor activity in various xenograft models.33 It remains active when orally administered,33 however, has not yet met criteria for advancement to Phase II clinical trials.34 Very recently, the 5′-acylated gemcitabine prodrugs with coumarin or boron-dipyrromethene/biotin conjugate have been reported for monitoring drug delivery at subcellular levels by fluorescence imaging.35,36

Figure 1.

The 4-N-acylated gemcitabine pro-drugs.

The 1-(2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl)cytosine ([18F]-FAC) was developed by Radu et. al.37 as a PET tracer possessing a substrate affinity for dCK and CDA comparable to gemcitabine. Determination of [18F]-FAC uptake and pretreatment levels of dCK serve as a non-invasive prognosticator for gemcitabine chemotherapy response.37-40 The dCK specific PET tracers such as 1-(2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-arabinofuranosyl)cytosine ([18F]-L-FAC) and 1-(2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-β-L-arabinofuranosyl)-5-methylcytosine (L-18F-FMAC), which possess no substrate affinity to CDA, were also developed to study uptake of [18F]-FAC serving as additional predictive tools for gemcitabine treatment response.41,42

Herein we report synthesis and cytostatic activity of a series of gemcitabine analogues with 4-N-alkanoyl or 4-N-alkyl chains modified with a terminal hydroxyl, halide or alkene groups. The 4-N-alkyl analogues stable towards deamination were designed to examine their anticancer activities and also to explore their compatibility with radiofluorination protocols.

Chemistry

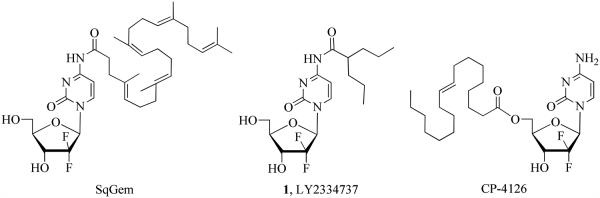

Condensation of gemcitabine (2a, dFdC) with undecanoic acid employing peptide coupling conditions25,43 [N-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethyl-carbodiimide (EDCI)/1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt)/N-methylmorpholine (NMM)] in DMF/DMSO (3:1) at 60 °C afforded the 4-N-undecanoylgemcitabine 3 (50%, Scheme 1). Analogous coupling of 2a with 8-nonenoic acid, 10-undecenoic acid, 12-tridecenoic acid, 11-fluoroundecanoic acid (S4; see Supporting Information) or 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid afforded the 4-N-acyl analogues 4-8 with 40% to 66% yields after silica gel purification. It is noteworthy that these couplings in the presence of HOBt typically progressed to >90% completion (TLC), while the 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole(CDI)-mediated coupling44 of 2a with the corresponding carboxylic acids in CH3CN and pyridine without HOBt proceeded less efficiently.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the lipophilic 4-N-alkanoyl gemcitabine derivatives.

Reagents and conditions: (a) R′(CH2)nCOOH/NMM/HOBt/EDCI/DMF/DMSO/60 °C/overnight; (b) (i) TMSCl/Pyr/CH3CN, 0 °C/2.5 h, (ii) BrCH2CH2(CH2)8COOH/CDI/CH3CN/65 °C/overnight; (c) BrCH2CH2(CH2)8COOH/ClCOOEt/Et3N/DMF (d) (Boc)2O/KOH/1,4-dioxane; (e) BrCH2CH2(CH2)8COCl/NaHCO3/CH2Cl2; (f) DAST/CH2Cl2; (g) TFA

Unexpectedly, the HOBt-promoted coupling of 2a with 11-bromoundecanoic acid led to the formation of the 4-N-[11-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yloxy)undecanoyl derivative 9 in a 53% yield rather than the expected 4-N-(11-bromoundecanoyl) derivative 12. Other attempts to synthesize the bromo derivative either by transiently protecting of 2a with a trimethylsilyl group45 followed by treatment with 11-bromoundecanoic acid/CDI or by employing a mixed anhydride procedure26 (11-bromoundecanoic acid/ethyl chloroformate/TEA) gave instead the chloro derivative 10. The labile nature of the terminal bromide necessitated an alternative approach for the preparation of 12. We found that condensation of 3′,5′-di-O-Boc-protected gemcitabine46 2b with 11-bromoundecanoyl chloride (S5; SI) provided the bromo derivative 11 in a 33% isolated yield. The deprotection of 11 with TFA gave desired 12 (86%). The coupling of 2b with 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid yielded the protected 4-N-(11-hydroxyundecanoyl) derivative 13 (37%), bearing the hydroxyl group at the alkyl chain suitable for further chemical modifications. Thus, fluorination of 13 with DAST afforded the 4-N-(11-fluoroundecanoyl) derivative 14 (40%). Deprotection of 13 or 14 with TFA gave 7 (87%) or 8 (82%), respectively.

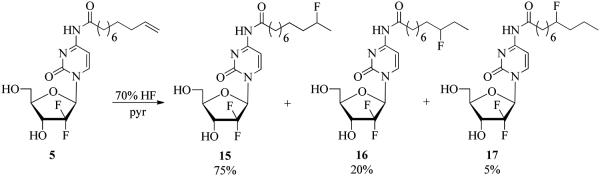

Recently, Haufe et al. established the methodology for radiofluorination of terminal olefins employing the [18F]-HF/pyridine reagent.47 We performed the model fluorination using this condition employing regular, non-radioactive HF/pyridine with the olefin 5. Thus, treatment of 5 with Olah’s Reagent (70% HF in pyridine) in an HDPE vessel at 0 °C for 2 h gave a regioisomeric mixture of 10-fluoro, 9-fluoro, and 8-fluoro derivatives 15-17 with an isomeric ratio of 75:20:5 (91%, Scheme 2). The 1H and 19F NMR spectra were diagnostic for the regioisomeric composition [19F δ −179.79 (m, 0.05 F), −178.83 (m, 0.1 F) and −170.27 (m, 0.75 F)]. Fluorination involved Markovnikov addition of HF to double bond while generation of the minor isomers 16 and 17 is attributed to migration of the carbocation along the chain during the addition reaction as has been observed before.48 Since addition of HF to 5 gave multiple products and radiolabeling with [18F]-HF was reported to proceed with low radiochemical efficiencies,47 while other commonly used fluorination protocols required conditions49 under which the 4-N-alkanoyl linkage might be cleaved, we turned our attention to developing 4-N-alkyl gemicitabine analogues.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the fluorinated 4-N-alkanoyl gemcitabine derivatives by the addition of HF to the olefin.

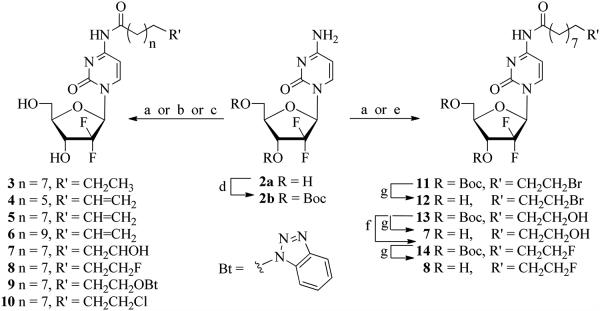

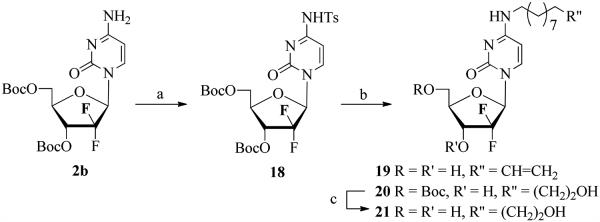

Synthesis of 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine derivatives, which to the best of our knowledge, are limited to short 4-N alkyl modifications and their anticancer activities have not been studied in depth.50 The 4-N-alkyl analogues are expected to be resistant to chemical hydrolysis as well as CDA-catalyzed deamination.51 From the available methods for the N-alkylation of cytosine nucleosides,52-55 we found that the alkylation of the 4-exocyclic amine group in gemcitabine was achieved efficiently by displacement of a 4-N-tosylamine group54 with an aliphatic alkyl amine. Thus, reaction of 2b with TsCl in the presence of Et3N in 1,4-dioxane afforded the protected 4-N-tosylgemcitabine 18 (45%, Scheme 3). Treatment of 18 with 10-undecenyl amine effected simultaneous displacement of the p-toluenesulfonamido group from the C4 position of the cytosine ring and deprotection to give the 4-N-(10-undecenyl) derivative 19. Analogous reaction of 18 with 11-aminoundecanol (S7; SI) gave the 5′ monoprotected 11-hydroxyundecanyl analogue 20 (47%) as the major product in addition to fully deprotected 21 (24%). Deprotection of 20 with TFA provided 21 with 38% overall yield from 18.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the 4-N-alkyl gemcitabine derivatives

Reagents and conditions: (a) TsCl/Et3N/1,4-dioxane; (b) CH2=CH(CH2)9NH2 or HOCH2CH2(CH2)9NH2; (c) TFA

Owing to instability of Boc protection group during displacement of the p-toluenesulfonamido group, we explored other protection strategies that would lead to gemcitabine derivatives suitable for the selective modification of the primary hydroxyl group on the 4-N-alkyl chain. Thus, transient protection of 2a with TMSCl and subsequent treatment with TsCl followed by methanolic ammonia afforded the 4-N-tosylgemcitabine 22 in 96% yield (Scheme 4). Displacement of the p-toluenesulfonamido group from 22 with O-benzyl protected 11-aminoundecanol (S11; SI) proceeded efficiently to give the 4-N-(11-benzyloxyundecanyl)gemcitabine 23 in 61% isolated yield. Subsequent treatment of 23 with BzCl yielded the fully protected analogue 24 (60%). The lengthy treatment of 24 with ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) effected the selective removal of the benzyl group to give the 3′,5′-di-O-benzoyl protected 11-hydroxyundecanyl analogue 25 (70%). It is noteworthy that attempted hydrogenolysis of 24 (H2/Pd-C/EtOH/24 h) produced 25 with the inconsistent yields of 5-50% in addition to substantial quantities of other byproducts including the 5,6-dihydro reduced derivative.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the 4-N-fluoroalkyl gemcitabine derivatives

Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) TMSCl/Pyr, (ii) TsCl, (iii) MeOH/NH3; (b) BnO(CH2)11NH2/Et3N/1,4-dioxane; (c) 2,6-Lutidine/DMAP/BzCl/CH2Cl2; (d) CAN/CH3CN; (e) DAST/CH2Cl2; (f) MeOH/NH3/rt; (g) MsCl/Et3N/CH2Cl2/0 °C; (h) KF/K2CO3/K222/CH3CN/110 °C, (ii) MeONa/MeOH/100 °C

Fluorination of 25 with DAST afforded the 4-N-(11-fluoroundecanyl) derivative 26 and subsequent deprotection with methanolic ammonia at room temperature gave the 4-N-fluoroalkyl analogue 27 (43% overall from 25). We also examined fluorination of 25 using conditions which are compatible with general radiosynthetic protocols for 18F labeling.46,56 Thus, reaction of 25 with MsCl/Et3N gave the mesylate precursor 28 (90%). Fluorination of the latter with KF/K2CO3/Kryptofix 2.2.2 in CH3CN at 110 °C for 18 minutes yielded the protected fluoro analogue 26 and subsequent debenzoylation with 0.5 M MeONa/MeOH at 100 °C for 8 minutes and purification by HPLC afforded the desired 4-N-fluoroalkyl gemcitabine 27 (overall 62% from 28; in total of 50 min). This fluorination protocol meets criteria for working with 18-fluorine isotope which has limited availability and short half-life (110 min.) and as such is applicable for labeling studies.

Cytostatic Activity

The growth inhibitory activities of the 4-N-acyl (3-8) and 4-N-alkyl (19, 21, 27) gemcitabine analogues were assessed on a panel of murine and human tumor cell lines (Table 1). All 4-N-alkanoyl 3-8 analogues demonstrated potent antiproliferative activities with the IC50 values in the range of low nM, similar to gemcitabine 2a acting probably as prodrugs as established before.25 On the other hand, the 4-N-alkylgemcitabine derivatives 19, 21, and 27 showed cytostatic activities at IC50 values in the low to modest μM range. It appears that the cytostatic activity only varies slightly between compounds with different chain lengths or functional groups. The activity for the 4-N-acyl gemcitabine derivatives were drastically diminished (almost by two orders of magnitude) in the dCK-deficient CEM/dCK- cell line implying again the role for dCK in the metabolism of these compounds.24 Interestingly, cytotoxicity of the 4-N-alkylgemcitabines 19, 21, and 27 in dCK-deficient CEM/dCK- cells was only 2-5 times lower. It is noteworthy that 4-N-valproylgemcitabine 1 in its free-base form showed cytostatic activity in the low μM range more comparable to our 4-N-alkyl analogues than the 4-N-acyl counterparts. The inhibitory activities for 1 are in agreement with the cytotoxicity described by Pratt et al. on a NCI-60 panel, who reported IC50 values of 1 being “80-fold more” than the value for gemcitabine on most cell lines.30

Table 1.

In vitro cytostatic activity of representative 4-N-modified analogues on the tumor cell lines L1210, CEM/0, CEM/dCK−, HeLa and MCF-7

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1210 | CEM/0 | CEM/dCK− | HeLa | MCF-7 | |

| 1a | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 161 ± 8 | 0.76 ± 0.30 | 0.55 ± 0.49 |

| 2a | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 0.0099 ± 0.0041 | 0.0072 ± 0.0002 |

| 3 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.060 ± 0.012 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 0.0089 ± 0.0024 | 0.0053 ± 0.0023 |

| 4 | 0.024 ± 0.017 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 20 ± 2 | 0.042 ± 0.005 | 0.0079 ± 0.0002 |

| 5 | 0.018 ± 0.016 | 0.071 ± 0.015 | 12 ± 9 | 0.012 ± 0.007 | 0.0062 ± 0.0029 |

| 6 | 0.021 ± 0.018 | 0.069 ± 0.002 | 6.8 ± 1.8 | 0.013 ± 0.007 | 0.0079 ± 0.0012 |

| 7 | 0.023 ± 0.003 | 0.24 ± 0.19 | 19 ± 6 | 0.049 ± 0.030 | 0.0081 ± 0.0005 |

| 8 | 0.053 ± 0.040 | 0.059 ± 0.009 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 0.011 ± 0.004 | 0.0077 ± 0.0006 |

| 19 | 7.0 ± 3.0 | 13 ± 6 | 60 ± 15 | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 28 ± 14 |

| 21 | 29 ± 11 | 86 ± 10 | 140 ± 28 | 22 ± 4 | 27 ± 3 |

| 27 | 28 ± 2 | 28 ± 4 | 134 ± 18 | 17 ± 4 | 26 ± 7 |

In free-base form.

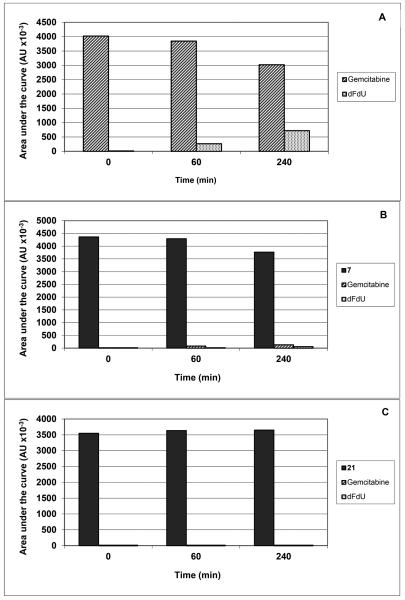

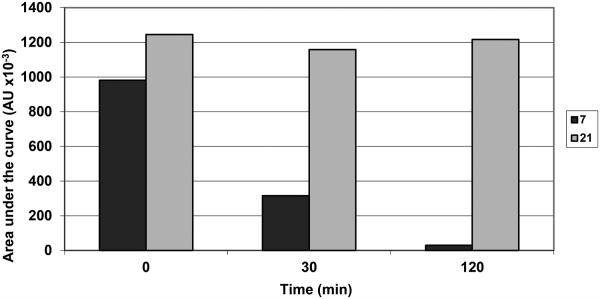

The selected compounds were also investigated for their interaction with dCK or mitochondrial thymidine kinase (TK-2) that has also 2′-deoxycytidine kinase activity. None of the prodrug derivatives showed significant inhibition of the phosphorylation of dCyd or dThd by dCK and TK-2, respectively. When directly evaluated as a potential substrate for dCK, the 4-N-alkanoyl derivatives 6 and 8 displayed very poor substrate activity (< 1%), whereas the 4-N-alkyl analogues 11 and 12 displayed no measurable substrate activity under experimental conditions that converted gemcitabine to its 5′-monophosphate by at least 15%. Taken together, these findings suggest the 4-N-alkanoyl analogues first need to be converted to gemcitabine before acting as an efficient substrate for dCK. This release of gemcitabine from the 4-N-alkanoyl prodrugs seems to occur quite efficiently given their pronounced cytostatic potential in the cell cultures, and the marked loss of cytostatic activity in the dCK-deficient CEM tumor cell cultures. Instead, the rather modest antiproliferative activities of the 4-N-alkyl analogues may be attributed, at least to certain extent, to a poor cellular uptake and/or to an inefficient conversion to the parental gemcitabine which may fall outside the assay detection limits (<1%). Moreover, the fact that the cytostatic activity of the 4-N-alkyl analogues are only moderately decreased in dCK-deficient CEM tumor cell cultures may not only confirm a poor, if any intracellular conversion to gemcitabine but also point to a potential different mechanism of cytostatic activity of these prodrugs. To gain insight into the metabolism of the 4-N-alkylgemcitabine derivatives, the stabilities of representative 4-N-alkanoyl 7 and 4-N-alkyl 21 analogues towards hydrolysis and resistance to enzymatic deamination were evaluated in parallel with gemcitabine in human serum and in murine liver extract. Figure 2 showed that gemcitabine was deaminated to its inactive uracil derivative dFdU as a function of time (panel A), while the 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine prodrug 7 was slowly converted to gemcitabine, which was then gradually deaminated to dFdU (panel B). On the other hand the 4-N-alkylgemcitabine derivative 21 was not deaminated nor was there any measurable conversion to gemcitabine observed (panel C). When 7 and 21 were exposed to the murine liver extract, 7 was rapidly converted to gemcitabine (and dFdU) whereas 21 was fully stable for at least 2 hours (Figure 3). These findings support again the assumption that 7 is enzymatically efficiently converted to gemcitabine whereas 21 is not, explaining the differences in the cytostatic activity of both compounds. Although the cellular target for the antiproliferative activity of the 4-N-alkyl analogues is currently unclear, it might well be different from inhibition of DNA synthesis.

Figure 2.

Time-point evaluation of the stability and resistance to deamination for gemcitabine (A), 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine 7 (B) and 4-N-alkylgemcitabine 21 (C) in 50% human serum in PBS.

Figure 3.

Time-point evaluation of the stability of 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine 7 and 4-N-alkylgemcitabine 21 in murine liver extract in PBS.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that coupling of gemcitabine with various carboxylic acids or reaction of 3′,5′-di-O-Boc-protected gemcitabine with acyl halides gave 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine analogues with a hydroxyl, fluoro, chloro, bromo or alkene functional group on the alkyl chain. Displacement of the p-toluenesulfonamido group from 4-N-tosylgemcitabine with alkyl amines provided 4-N-alkylgemcitabine analogues suitable for further chemical modifications including fluorination compatible with the synthetic protocols for 18F labeling. The 4-N-alkanoylgemcitabine analogues showed potent antiproliferative activities against the L1210, CEM, HeLa and MCF-7 cell lines with the IC50 values in the range of low nM while the cytostatic activity of the 4-N-alkylgemcitabine derivatives was in the low to modest μM range. The 4-N-alkanoyl derivatives display significant cytostatic activity, acting as efficient prodrugs, while the 4-N-alkyl analogues appear to attain their modest activity without “measurable” conversion to gemcitabine. The cytostatic activity appears to be independent of the length of alkyl chain and varies slightly for the different functional groups present on the molecule.

Experimental Part

The 1H (400 MHz), 13C (100 MHz), or 19F (376 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature in solutions of CDCl3 or MeOH-d4 or DMSO-d6, as noted. The reactions were followed by TLC with Merck Kieselgel 60-F254 sheets and products were detected with a 254 nm light or with Hanessian’s stain. Column chromatography was performed using Merck Kieselgel 60 (230-400 mesh). Reagent grade chemicals were used and solvents were dried by reflux distillation over CaH2 under nitrogen gas, unless otherwise specified, and reactions carried out under Ar atmosphere. The carboxylic acid and amine derivatives used for the coupling with gemcitabine were commercially available except for 11-fluoroundecanoic acid (S4), 11-bromoundecanoyl chloride (S5), 11-aminoundecanol (S7) and 11-benzyloxyundecan-1-amine (S11) which synthesis is described in Supporting Information. The purity of the synthesized compounds was determined to be ≥95% by elemental analysis (C, H, N) and/or HPLC on Phenomenex Gemini RP-C18 with isocratic mobile phase (50% CH3CN/H2O) and flow rate of 5 mL/min. Representative HPLC chromatograms are included in the Supporting Information Section.

Tumor cell and enzyme sources

Murine leukemia L1210, human lymphocyte CEM and human cervix carcinoma HeLa cell lines were obtained from ATCC, Rockville, MD. Human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells were a kind gift from G. Peters (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The dCK-deficient CEM cell line was obtained upon selection in the presence of araC and found to be deficient in cytosolic dCK activity.

General synthetic procedure for preparation of the 4-N-acyl gemcitabine derivatives (3-10). Procedure A

N-Methylmorpholine (1.1 eq.), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (1.1 eq.), the appropriate carboxylic acid (1.1 eq.) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (1.3 eq.) were sequentially added to a stirred solution of gemcitabine hydrochloride (2a, 1.0 eq.) in DMF/DMSO (3:1, 2 mL) at ambient temperature under Argon. The reaction mixture was then gradually heated to 65 °C (oil-bath) and kept stirring overnight. After the reaction was completed (TLC), the reaction mixture was cooled to 15 °C and partitioned between a small amount of brine and EtOAc. The organic phase was separated and the aqueous layer extracted with fresh portions of EtOAc (3 x 30 mL). The combined organic layers was then sequentially washed with 20% LiCl/H2O, saturated NaHCO3/H2O, brine, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to give the crude products 3-10.

4-N-(Undecanoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (3)

Treatment of 2a (34 mg, 0.11 mmol) with commercially available undecanoic acid (23.3 mg, 0.120 mmol) by Procedure A gave 45.7 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 3 (23.8 mg, 50%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 0.90 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.27-1.39 (m, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.63-1.70 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.79-3.83 (m, 1H, H5′), 3.94-3.99 (m, 2H, H5′, H4′), 4.31 (dt, J = 20.8, 10.5 Hz, 1H, H3′), 6.24-6.28 (m, 1H, H1′), 7.50 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.34 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) 14.41, 23.69, 25.93, 30.15, 30.40, 30.40, 30.56, 30.64, 33.03, 38.16, 60.29 (C5′), 70.21 (“t,” J = 23.1 Hz, C3′), 82.86 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, C4′), 86.44 (dd, J = 26.6, 38.3 Hz, C1′), 98.26 (C5′), 123.90 (t, J = 259.3 Hz, C2′), 145. 94 (C6), 157.65 (C2), 164.80 (C4), 175.97; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.09 (br. d, J = 240.9 Hz, 1F), −119.14 (dd, J = 11.3, 240.9 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H31F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 454.2124; found 454.2136.

4-N-(8-Nonenoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (4)

Treatment of 2a (34 mg, 0.110 mmol) with commercially available 8-nonenoic acid (21 μL, 19.5 mg, 0.120 mmol) by Procedure A gave 29.0 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (70 → 100% EtOAc/hexane) to give 4 (20 mg, 45%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.32-1.46 (br. s, 6H, 3 x CH2), 1.65-1.69 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.03-2.07 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (dd, J = 12.3, 2.8 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.96-3.99 (m, 2H, H5″, H4′), 4.30 (td, J = 12.2, 8.6 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.90-5.01 (m, 2H, CH2), 5.81 (ddt, J = 16.9, 10.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H, CH), 6.24-6.28 (m, 1H, H1′), 7.50 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.34 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.90, 29.87, 29.90, 30.00, 34.79, 38.15, 60.31 (C5′), 70.23 (dd, J = 21.9, 23.4 Hz, C3′), 82.86 (C4′), 86.14 (d, J = 20.1 Hz, C1′), 98.28 (C5) , 114.83, 123.94 (t, J = 259.2 Hz, C2′), 140.03, 145.97 (C6) , 157.37 (C2), 164.84 (C4), 175.97; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.13 (br. d, J = 242.5 Hz, 1F), −119.21 (dd, J = 11.4, 240.0 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C18H25F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 424.1654; found 424.1656.

4-N-(10-Undecenoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (5)

Treatment of 2a (40 mg, 0.134 mmol) with commercially available undecylenic acid (31 μL, 28 mg, 0.148 mmol) by Procedure A gave 114 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (80 → 100% EtOAc/hexane) to give 5 (38 mg, 66%) as a white solid: UV (CH3OH) λmax 252 nm (ε 15 150), 286 nm (ε 8950), λmin 228 nm (ε 5900), 275 nm (ε 8650); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.23-1.29 (br. s, 8H, 4 × CH2), 1.30-1.39 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.50-1.57 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.01 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.40 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.66 (“br. d,” J = 12.4 Hz, 1H, H5″), 3.81 (br. d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.89 (dt, J = 8.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H, H4′), 4.19 (“q,” J = 10.6 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.93 (“d. quin,” J = 10.1, 1.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.99 (“d. quin,” J = 17.2, 1.7 Hz, 1H, CH), 5.33 (br. t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, OH), 5.79 (tdd, J = 6.6, 10.3, 17.1 Hz, 1H, CH), 6.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 6.35 (br. s, 1H, OH), 7.29 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.24 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 10.98 (br. s, 1, NH); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.95, 30.08, 30.15 (2 x CH2), 30.37, 30.39, 34.88, 38.18, 60.32 (C5′), 70.24 (dd, J = 21.9, 23.4 Hz, C3′), 82.89 (dd, J = 2.7, 5.2 Hz, C4′), 86.48 (dd, J = 25.8, 38.2 Hz, C1′), 98.28 (C5), 114.73, 123.93 (t, J = 259.2 Hz, C2′), 140.13, 145.97 (C6), 157.69 (C2), 164.83 (C4), 176.00; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.09 (br. d, J = 239.6 Hz, 1F), −119.16 (dd, J = 10.9, 239.9 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 430 (100, [M+H]+). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H29F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 452.1967; found 452.1982. Elemental Anal. calcd for C20H29F2N3O5•0.5H2O (438.47): C, 54.79; H, 6.90; N, 9.58. Found: C, 54.48; H, 6.53; N, 9.21.

4-N-(12-Tridecenoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (6)

Treatment of 2a (30 mg, 0.1 mmol) acid (23 mg, 0.11 mmol) by Procedure A gave 43.1 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (70 → 80% EtOAc/hexane) to give 6 (20.1 mg, 44%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.27-1.38 (m, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.66 (quin, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.04 (dd, J = 14.3, 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (dd, J = 12.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H, H5′), 4.07-3.88 (m, 2H, H5″, H4′), 4.31 (dt, J = 20.8, 10.4 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.89-5.00 (m, 2H, CH2), 5.80 (ddt, J = 17.0, 10.2, 6.7 Hz, 1H, CH), 6.26 (“t,” J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.50 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.34 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.94, 30.11, 30.15, 30.20, 30.39, 30.53 (2 x CH2), 30.62, 34.87, 38.16, 60.30, 70.24 (“t,” J = 23.1 Hz, C3′), 82.83 (C4′), 86.46 (“t,” J = 32.2 Hz, C1′), 98.26 (C5), 114.67, 123.1 (t, J = 260.1 Hz, C2′), 140.14, 145.95 (C6), 157.68 (C2), 164.82 (C4), 176.0; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.13 (br. d, J = 239.4 Hz, 1F), −119.21 (dd, J = 9.3, 239.3 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C22H33F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 480.2280; found 480.2289.

4-N-(11-Hydroxyundecanoyl)- 2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (7)

Treatment of 2a (58 mg, 0.194 mmol) with commercially available 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid (43 mg, 0.213 mmol) by Procedure A gave 75.5 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (7.5% MeOH/CHCl3) to give 7 (35 mg, 40%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.33 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.49-1.54 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.66 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.53 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.81 (dd, J = 3.1, 12.8 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.94-3.99 (m, 2H, H4′, H5′), 4.26-4.34 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.26 (“t,” J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.49 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.33 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.93, 26.94, 30.13, 30.37, 30.48, 30.53, 30.64, 33.65, 38.17, 60.30 (C5′), 63.01, 70.23 (“t,” J = 23.0 Hz, C3′), 82.88 (“d,” J = 9.0 Hz, C4′), 86.47 (“dd,” J = 27.0, 37.6 Hz, C1′), 98.25 (C5), 123.91 (t, J = 258.9 Hz, C2′), 145.95 (C6), 157.67 (C2), 164.82 (C4), 176.00; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.16 (“br. d,” J = 239.0 Hz, 1F), −119.21 (dd, J = 10.5, 242.6 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H31F2N3NaO6 [M+Na]+ 470.2073; found 470.2073.

4-N-(11-Fluoroundecanoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (8)

Treatment of 2a (69.8 mg, 0.233 mmol) with 11-fluoroundecanoic acid (S4, 52 mg, 0.256 mmol) by Procedure A gave 82.7 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (70% EtOAc/hexane) to give 8 (42.1 mg, 41%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.35 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.62-1.74 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 2.47 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.83 (dd, J = 3.0, 12.8 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.96-4.02 (m, 2H, H5″, H4′), 4.32 (dt, J = 8.6, 12.2 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.42 (dt, J = 6.1, 47.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 6.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.35 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.95, 26.35, 30.16, 30.38, 30.48, 30.59, 31.50, 31.69, 38.17, 60.29(C5′), 70.20 (“t,” J = 23.0 Hz, C3′), 82.85 (“dd,” J = 2.3, 3.6 Hz, C4′), 84.89 (d, J = 163.8 Hz, CH2F), 86.47 (dd, J = 29.6, 34.7 Hz, C1), 98.29 (C5), 123.94 (t, J = 259.2 Hz, C2′), 145.96 (C6), 157.69 (C2), 164.83 (C4), 176.01; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −219.87 (tt, J = 24.7, 47.5 Hz, 1F), −120.09 (br. d, J = 239.0 Hz, 1F), −119.17 (br. dd, J = 10.2, 239.0Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 450 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (+ESI) m/z calcd for C20H30F3N3Na3O5 [M+Na]+ 472.2023; found 472.2011.

4-N-[11-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yloxy)-undecanoyl]-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (9)

Treatment of 2a (50 mg, 0.167 mmol) with commercially available 11-bromoundecanoic acid (48.7 mg, 0.184 mmol) by Procedure A gave 85.5 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 9 (50 mg, 53%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.28 (br. s, 10H, CH2), 1.45-1.57 (m, 4H, CH2), 1.73-1.80 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.40 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.66 (“br. d,” J = 13.6 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.80 (“br. d,” J = 13.6 Hz, 1H, H5″), 3.89 (dt, J = 2.7, 8.4 Hz, 1H, H4′) , 4.20 (“br. dt,” J = 9.1, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.55 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 5.35 (“br. t,” J = 4.6 Hz, 1H, OH), 6.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 6.39 (br. s, 1H, OH), 7.28 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.48 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar), 7.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar), 7.82 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar), 8.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar), 8.25 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 10.99 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CD3OD) 25.90, 26.64, 29.12, 30.06, 30.24, 30.28, 30.35, 30.40, 38.14, 58.32, 60.30, 70.23 (“t,” J = 23.1 Hz, C3′), 82.32, 82.89 (m, C4′), 98.25 (C5), 110.16, 120.50, 123.92, 126.38, 128.72, 129.55, 144.49, 145.95, 157.66, 164.81, 175.99; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.09 (br. d, J = 239.0 Hz, 1F), −119.14 (dd, J = 243.7, 12.3 Hz, 1F); HRMS (+ESI) m/z calcd for C26H34F3N6NaO6 [M+Na]+ 587.2406; found 587.2442.

4-N-(11-Chloroundecanoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (10).

Method A. TMSCl (79 μL, 68 mg, 0.630 mmol) was added to a suspension of 2a (150 mg, 0.500 mmol) in Pyr/MeCN (3:1, 2 mL) at 0 °C under Ar and stirred for 2.5 h, resulting in a clear solution. In a separate vessel, carbonyldiimidazole (CDI, 22.5 mg, 0.138 mmol) was added to a solution of 11-bromoundecanoic acid (36.5 mg, 0.138 mmol) in MeCN (1 mL) portion-wise and stirred at ambient temperature. After 30 minutes, the latter solution was combined with the previously prepared solution of transiently protected nucleoside and the new reaction mixture was stirred at 65 °C overnight. After 19 h, EtOH (2 mL) was added and mixture followed by H2O (4 mL) and the solution stirred at 65 °C for 20 min. The volatiles were then evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was partitioned between EtOAc and H2O, the pH was adjusted to 2.0 with phosphoric acid, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layer was washed with saturated NaHCO3/H2O, brine, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (47.2 mg) was column chromatographed (70% EtOAc/hexane) to give 10 (11 mg, 5%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.34 (br. s, 10H, 2 x CH2), 1.41-1.49 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.66-1.71 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.73-1.82 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.47 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.56 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.83 (“dd,” J = 12.7, 3.1 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.96-4.03 (m, 2H, H5″, H4′), 4.27-4.37 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.28 (“t,” J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.36 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.94, 27.93, 29.94, 30.13, 30.35, 30.43, 30.51, 33.83, 38.15, 45.74, 60.31 (C5′), 70.25 (C3′), 82.89 (C4′), 86.81 (C1′), 98.26 (C5), 123.93 (t, J = 258.0 Hz, C2′), 145.97 (C6), 157.71 (C2), 164.86 (C4), 176.02 (CO); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.13 (br. d, J = 240.2 Hz, 1F), −119.2 (br. dd, J = 10.9, 240.2 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 466 (100, [M+H]+ for 35Cl), 468 (100, [M+H]+ for 37Cl); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H3035ClF2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 488.1734; found 488.1742.

Method B. Et3N (28 μL, 0.200 mmol) was added to a mixture of 11-bromoundecanoic acid (26.6 mg, 0.100 mmol) in THF (1 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under Ar. The reaction mixture was then cooled to −15 °C followed by the dropwise addition of a solution of ClCO2Et (19 μL, 0.200 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL) with continued stirring. After 15 minutes, a solution of 2a (30 mg, 0.100 mmol) in DMF/DMSO (2.5 mL, 1.5:1) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture allowed to warm up to ambient and kept stirring overnight. After 24 h, the reaction was treated with NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc (3x). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was column chromatographed (70% EtOAc/hexane) to give 10 (7 mg, 15%) with data as above.

4-N-(11-Bromoundecanoyl)-3′,5′-di-O-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (11)

A solution of 2b46 (35.5 mg, 0.077 mmol) and NaHCO3 (400 mg, 4.76 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL) was added to a stirred solution of 11-bromoundecanoyl chloride (S5, 0.1 mL, 122 mg, 0.43 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) at 0°C under Ar. After 15 minutes, the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to ambient temperature and kept stirring for 3 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by addition of saturated NaHCO3/H2O, the mixture partitioned with water and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 x 10 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (141.0 mg) was chromatographed (25% EtOAc/hexane) to give 11 (18 mg, 33%) as a colorless oil: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.30 (br. s, 10H, 5 x CH2), 1.40-1.45 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.53 (s, 18H, 6 x CH3), 1.68 (“quin,” J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.86 (“quin,” J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.48 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.42 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.37-4.50 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′,5″), 5.14 (“dt,” J = 4.5, 11.2 Hz, 1H, H3′), 6.46 (dd, J = 7.3, 9.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 9.05 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 24.77, 27.54, 27.70, 28.14, 28.72, 28.96, 29.22, 29.26, 29.33, 32.82, 34.07, 37.58, 63.87 (C5′), 72.64 (dd, J = 17.2, 34.0 Hz, C3′), 77.79 (C4′), 83.37, 84.21 (m, C1′), 84.83, 97.02 (C5), 120.40 (dd, J = 260.7, 267.3 Hz, C2′), 145.27 (C6), 151.42, 152.91, 153.94 (C2), 163.40 (C4), 174.17; 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −120.00 (br. d, J = 246.9 Hz, 1F), −115.57 (dt, J = 11.4, 246.9Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 710 (100, [M+H]+ for 79Br), 712 (100, [M+H]+ for 81Br).

4-N-(11-Bromoundecanoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (12)

Compound 11 (32 mg, 0.045 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (1.0 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 20 °C. After 4 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with toluene, the volatiles were evaporated, and the residue co-evaporated with a fresh portion of toluene. The resulting residue (32 mg) was column chromatographed (80 → 100% EtOAc/hexane) to give 12 (19.9 mg, 86%) as a colorless solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.31–1.41 (m, 10H, 5 x CH2), 1.41-1.52 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.63-1.73 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.81-1.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.47 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.45 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.75-3.89 (m, 1H, H5″), 3.93-4.05 (m, 2H, H4′, H5″), 4.32 (dt, J = 8.5, 12.2 Hz, 1H, H3′), 6.28 (“t,” J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.35 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 25.94, 29.17, 29.80, 30.13, 30.34, 30.43, 30.48, 34.01, 34.42, 38.17, 60.32 (C5′), 70.25 (dd, J = 22.2, 23.6 Hz, C3′), 82.88 (‘d’, J = 8.6 Hz, C4′), 86.48 (dd, J = 26.6, 37.6 Hz, C1), 98.29 (C5), 123.93 (t, J = 259.9 Hz, C2′), 145.98 (C6), 157.69 (C2), 164.84 (C4), 176.03;19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.10 (br. d, J = 240.0 Hz, 1F), −119.17 (ddd, J = 3.9, 12.1, 240.0 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 510 (100, [M+H]+ for 79Br), 512 (100, [M+H]+ for 81Br); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H3079BrF2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 532.1229; found 532.1239.

4-N-(11-Hydroxyundecanoyl)-3′,5′-di-O-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (13)

Treatment of 2b (39 mg, 0.084 mmol) with 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid (29 mg, 0.14 mmol) by Procedure A gave 102 mg of the crude product, which was then column chromatographed (55 → 65% EtOAc/hexane) to give 13 (20 mg, 37%) as a colorless oil: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.30 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.53 (s, 18H, 6 x CH3), 1.58 (“quin,” J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.69 (“quin,” J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.47 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.65 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.37-4.50 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′,5″), 5.14 (“dt,” J = 4.8, 11.1 Hz, 1H, H3′), 6.46 (dd, J = 7.2, 9.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 9.08 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 24.75, 25.65, 27.53, 27.69, 28.88, 29.11, 29.16, 29.27, 29.38, 32.75, 37.78, 62.99, 63.88 (C5′), 72.67 (dd, J = 17.0, 33.8 Hz, C3′), 77.73 (C4′), 83.33, 84.16 (dd, J = 18.2, 37.9 Hz, C1′), 84.77, 97.08 (C5), 120.42 (t, J = 263.8 Hz, C2′), 144.78 (C6), 151.44, 152.93, 154.67 (C2), 162.93 (C4), 173.46; 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −120.00 (br. d, J = 246.7 Hz, 1F), −115.58 (dt, J = 11.4, 246.7Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 648 (100, [M+H]+).

Treatment of 13 (4.0 mg, 0.008 mmol) with TFA as descibed for 12 gave 7 (3.1 mg, 87%) with data sa reported above.

4-N-(11-Fluoroundecanoyl)-3′,5′-di-O-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (14)

A chilled (−78°C) solution of DAST (6.2 μL, 7.6 mg, 0.048 mmol,) in CH2Cl2 (500 2μ) was added to a stirred solution of 13 (9.8 mg, 0.016 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.5 mL) at −78°C. After 30 minutes, the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to ambient temperature and kept stirring. After 2 h, the reaction mixture was then poured into a separatory funnel containing a chilled solution of NaHCO3/H2O (10 mL, pH=8) and was then extracted with CHCl3 (3 x 10 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (14 mg) was column chromatographed (5% MeOH/CHCl3) to give 14 (4.2 mg, 40%) as a colorless oil: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.28 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.51 (s, 9H, t-Bu), 1.52 (s, 9H, t-Bu), 1.60-1.78 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 2.45 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.38-4.47 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′, H5″), 4.44 (dt, J = 6.2, 47.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 5.12-5.15 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.43 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.51-7.54 (m, 1H, H5), 7.87 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −217.97 (dt, J = 25.0, 47.4 Hz, 2F), −120.27 (br. d, J = 240.7 Hz, 1F), −115.77 (dt, J = 10.9, 247.4 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C30H46F3N3NaO9 [M+Na]+ 672.3078; found 672.3096.

Treatment of 14 (4.0 mg, 0.008 mmol) with TFA as descibed for 12 gave 8 (2.9 mg, 82%) with data sa reported above.

4-N-(10-Fluoroundecanoyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (15)

Chilled hydrogen fluoride/pyridine (70%, 1.0 mL) was added to 5 (20 mg, 0.044 mmol) in an HDPE vessel at 0 °C and stirred. After 2 h, the reaction mixture was treated with saturated NaHCO3/H2O (10 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 x 10 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (24.6 mg) was then column chromatographed (70% EtOAc/hexane) to give 15 (19 mg, 91%; isomeric mixture of 15:16:17 in 75:20:5 ratio) as a white solid: UV (CH OH) λmax 250 nm (ε 13 250), 298 nm (ε 5350), λmin 226 nm (ε 4650), 279 nm (ε 4700); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.22 (br. d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.27 (br. s, 8H, 4 x CH2), 1.29 (br. s, 2H, CH2), 1.44-1.62 (m, 5H, CH2, CH3), 2.40 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.66 (dt, J = 12.5, 4.3 Hz, 1H, H5″), 3.81 (“br. d,” J = 12.0 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.89 (“br. d,” J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, H4′), 4.19 (sep, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.64 (dsex, J = 49.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 5.31 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, OH), 6.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 6.33 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, OH), 7.29 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 8.24 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 10.98 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.30, 24.42, 24.46, 28.37, 28.57, 28.71, 28.74, 36.13, 36.35, 58.78 (C5′), 68.37 (t, J = 22.5 Hz, C3′), 81.01 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, C4′), 84.50 (d, J = 82.2 Hz, C1′), 90.53 (d, J = 162.9 Hz), 95.87 (C5), 124.18 (d, J = 260.1 Hz, C2′), 144.68 (C6), 154.17 (C2), 162.85 (C4), 174.06; 19F NMR (DMSO-d6) δ −170.27 (symmetric m, 0.75F), δ −116.91 (br. s, 2F); MS (ESI) m/z 450 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H30F3N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 472.2030; found 472.2048. Elemental Anal. Calcd for C20H30F3N3O4•H2O•0.33CH3CN (481.03): C, 51.59; H, 6.91; N, 9.70. Found: C, 51.36; H, 6.89; N, 9.97.

Minor isomers 16 [4-N-(9-Fluoroundecanoyl)] and 17 [4-N-(8-Fluoroundecanoyl)] had the following distinguishable peaks: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 4.41 (d quin, J = 49.6, 5.8 Hz, 0.2, CHF); 19F NMR (DMSO-d6) δ −179.79 (symmetric m, 0.15F), −178.83 (m, 0.1F), −116.91 (br. s, 2F).

4-N-(p-Toluenosulfonyl)-3′,5′-di-O-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (18)

Et3N (1.45 mL, 10.5 mmol) and TsCl (997 mg, 5.2 mmol) were added to a solution of 2b (242 mg, 0.52 mmol) in dry 1,4-dioxane (4.0 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under Ar. The tightly sealed reaction mixture was then gradually heated to 65 °C and kept stirring. After 24 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc, partitioned with saturated NaHCO3/H2O solution, and the aqueous layer was then extracted with EtOAc (2x). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (403 mg) was then column chromatographed (35% EtOAc/hexane) to give 18 (146 mg, 45%) as a colorless, solidifying oil: 1H NMR δ 1.49 (s, 9H, 3 x CH3), 1.52 (s, 9H, 3 x CH3), 2.43 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.46–4.32 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′, 5″), 5.11 (ddd, J = 4.0, 5.3, 12.8 Hz, 1H, H3′), 5.80 (br. s, 1H, H5), 6.24 (dd, J = 6.6, 10.6 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar), 7.48 (dd, J = 1.9, 8.1, Hz, 1H, H6), 7.84 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, Ar), 10.96 (br. s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR δ 21.54, 27.51, 27.65, 63.80 (C5′), 72.40 (dd, J = 16.9, 33.8 Hz, C3′), 78.02 (dd, J = 2.2, 4.7 Hz, C4′), 83.31 (dd, J = 20.6, 38.7 Hz, C1′), 83.41, 84.99, 98.41 (C5), 120.38 (dd, J = 260.2, 266.5 Hz, C2′), 126.71 (Ar), 129.58 (Ar), 138.26 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, Ar), 139.88 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, C6), 143.74 (Ar), 147.16 (C2), 151.35, 152.82, 154.82 (C4); 19F NMR δ −120.59 (br. d, J = 247.6 Hz, 1F), −115.80 (br. d, J = 247.6 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 618 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C26H33 F2N3NaO10S [M+Na]+ 640.1747; found 640.1754.

4-N-(10-Undecenyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (19)

In a tightly sealed vessel, a mixture of 18 (40 mg, 0.065 mmol) and 1-amino-10-undecene (0.50 mL, 404 mg, 2.4 mmol) was stirred at 60 °C. After 30 h, the volatiles were evaporated the resulting residue was column chromatographed (8% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 19 (9.5 mg, 36%) as colorless viscous oil: UV (CH3OH) λmax 268 nm (ε 11 600), λmin 228 nm (ε 7800); 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.43-1.30 (m, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.65-1.56 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.03-2.09 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.39 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.80 (dd, J = 3.3, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.89 (td, J = 2.8, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H4′), 3.95 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5″), 4.26 (dt, J = 8.3, 12.1 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.91-5.02 (m, 2H, CH2), 5.82 (tdd, J = 6.7, 10.3, 17.0 Hz, 1H, CH), 5.87 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.23 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.74 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 28.01, 29.98, 30.12, 30.19, 30.42, 30.51, 30.63, 34.88, 41.75, 60.56 (C5′), 70.67 (dd, J = 22.4, 23.8 Hz, C3′), 82.26 (dd, J = 3.6, 5.0 Hz, C4′), 85.94 (dd, J = 26.0, 38.0 Hz, C1), 97.33 (C5), 114.68, 124.05 (t, J = 258.4 Hz, C2′), 140.16, 140.77 (C6), 158.30 (C2), 165.37 (C4); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −119.89 (br. d, J = 240.1 Hz, 1F), −118.80 (br. d, J = 240.1 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 416 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H31F2N3NaO4 [M+Na]+ 438.2175; found 438.2178; Elemental Anal. Calcd for C20H31F2N3O4•0.5H2O•0.5CH3CN (445.01): C, 56.68; H, 7.59; N, 11.02. Found: C, 56.93; H, 7.77; N, 10.76.

4-N-(11-Hydroxyundecanyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (21)

11-Amino-1-undecanol (S7; 88 mg, 0.47 mmol) and Et3N (0.5 mL) were added to a solution of 18 (23.2 mg, 0.038 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (0.5 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under Ar. The reaction mixture was then gradually heated to 65 °C (oil bath) and kept stirring overnight. After 40 h, the volatiles were evaporated and the residue (97 mg) was column chromatographed (1 → 3% MeOH/EtOAc) to give mono-protected product 20 [9.5 mg, 47%: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.32 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.49 (s, 9H, t-Bu), 1.49-1.61 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.49-3.62 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.17 (dt, J = 9.9, 19.4 Hz, 1H, H4′), 4.02-4.09 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.48 (dd, J = 2.6, 12.4 Hz, 1H, H5′), 4.33 (dd, J = 4.3, 12.4 Hz, 1H, H5″), 5.86 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, H5), 6.25 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H, H1′), 7.51 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, C6); MS (ESI+) m/z 534 (100, [M+H]+)] followed by 21 (4 mg, 24%) of 90% purity. Compound 20 (9.5 mg, 0.018 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (1.0 mL) and reaction mixture was stirred at 18 °C. After 5 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with toluene (2 mL), the volatiles were evaporated, and the residue was co-evaporated with a toluene (2 x 1 mL). The resulting residue (17 mg) was then column chromatographed (1% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 21 (2.2 mg, 29% from 20; 38% overall from 18) as a colorless oil: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.30-1.41 (m, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.50-1.57 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.58-1.64 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.39 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.55 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.80 (dd, J = 3.3, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.89 (td, J = 2.8, 8.3 Hz, 1H, H4′), 3.95 (br. dd, J = 2.0, 12.6, 1H, H5″), 4.26 (dt, J = 8.3, 12.1 Hz, 1H, H3′), 5.87 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.23 (“t,” J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.74 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 26.94, 28.01, 29.97, 30.42, 30.58, 30.63, 30.66, 30.71, 33.67, 41.74, 60.56 (C5′), 63.03, 70.63 (dd, J = 22.0, 24.8 Hz, C3′), 82.23 (dd, J = 3.8, 5.0 Hz, C4′), 85.82 (C1), 97.32 (C5), 124.04 (t, J = 259.8 Hz, C2′), 140.77 (C6), 158.29 (C2), 165.37 (C4); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −119.90 (br. d, J = 239.2 Hz, 1F), −118.83 (dd, J = 11.6, 239.2Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 434 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H33F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 456.2280; found 456.2287.

4-N-(p-Toluenosulfonyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (22)

TMSCl (5.1 mL) was added to a suspension of 2a (600 mg, 2.0 mmol) in anhydrous pyridine (10 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature under Ar. After 2 h, TsCl (3.8 g, 20.027 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture gradually heated to 60 °C (oil-bath) and kept stirring. After 20 h, volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was treated with MeOH/NH3 (10 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature overnight. After 24 h, volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was column chromatographed (90% EtOAc/hexane) to give 22 (808 mg, 96%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 2.42 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.78 (dd, J = 3.4, 12.8 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3.90-3.95 (m, 2H, H4′, H5″), 4.28 (dt, J = 8.4, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H3′), 6.13 (“dd,” J = 5.3, 9.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 6.65 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H5), 7.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar), 7.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, Ar), 7.99 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 21.43, 60.34 (C5′), 70.21 (dd, J = 18.8, 27.2 Hz, C3′), 82.99 (d, J = 8.4, C4′), 85.46 (dd, J = 23.9, 41.3 Hz, C1′), 98.46 (C5), 123.84 (t, J = 258.7 Hz, C2′), 127.58 (Ar), 130.52 (Ar), 140.71 (Ar), 142.62 (C6), 144.66 (Ar), 150.21 (C2), 160.54 (C4); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.17 (br. s, 1F), −119.41 (dd, J = 4.1, 12.7 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 440 (100, [M+Na]+. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C16H17F2N3NaO6S [M+Na]+ 440.0698; found 440.0711.

4-N-(11-Benzyloxyundecanyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (23)

In a tightly sealed container, a solution of 22 (158 mg, 0.383 mmol), 11-(benzyloxy)undecanyl amine (S11; 945 mg, 3.41 mmol) and TEA (2 mL) in 1,4-dioxane was stirred at 75 °C. After 96 h, the volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was column chromatographed (1% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 23 (122 mg, 61%): 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.28 (br. s, 10H, 5 x CH2), 1.32 (br. s, 4H, 2 x CH2), 1.54-1.61 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.36 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.47 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.79 (dd, J = 3.3, 12.6, 1H, H5′), 3.88-3.96 (m, 2H, H4′, H5″), 4.25 (dt, J = 8.3, 12.0 Hz, 1H, H3′), 4.48 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.89 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H1′), 7.32 (“br. s,“ 5H, Ar), 7.70 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 27.23, 28.00, 29.96, 30.42, 30.48, 30.60, 30.63, 30.65, 30.71, 41.74, 60.54, 68.14 (C3′), 71.44, 73.86, 82.24 (“t,” J = 2.95 Hz, C4′), 85.92 (“dd,” J = 26.7, 37.7 Hz, C1′), 97.31 (C5), 124.04 (t, J = 258.7 Hz, C2′), 128.62, 128.84, 129.35, 139.87, 140.75, 158.27, 165.34; 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ-119.47 (br. d, J = 236.7 Hz, 1F), −118.42 (dd, J = 8.6, 236.7 Hz, 1F); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C27H39F2N3NaO5 [M+Na]+ 546.2750; found 546.2774.

4-N-(11-Benzyloxyundecanyl)-3′,5′-di-O-benzoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (24)

BzCl (50 μL, 0.49 mmol) was added to a solution of 23 (117 mg, 0.22 mmol), 2,6-Lutidine (64 μL, 0.89 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (27 mg, 0.22 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and stirred at 35 °C under Argon. After 20 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (40 mL), partitioned with H2O, and the aqueous layer extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 x 20 mL). The combined organic layer was sequentially washed with 1M HCl (20 mL), saturated NaHCO3/H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (157 mg) was column chromatographed (1% MeOH/CHCl3) to give 24 (50.6 mg, 60%) as a mixture of rotamers (80:20). The major rotamer had the following peaks: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.24 (br. s, 12H, 6 x CH2), 1.51-1.62 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.20 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.39 (t, J = 12.3 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.48 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.49-4.53 (m, 1H, H5′), 4.63-4.67 (m, 1H, H5′), 4.73-4.79 (m, 1H, H4′), 5.54 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 5.57-5.61 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.60-6.65 (m, 1H, H1′), 7.26-7.33 (m, 5H, Ar), 7.41-7.49 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.55-7.64 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.02-8.08 (m, 4H, Ar); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ −120.48 (br. d, J = 246.7 Hz, 1F), −115.34 (dt, J = 13.6, 246.7 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 754 (100, [M+Na]+. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C41H47F2N3NaO7 [M+Na]+ 754.3274; found 754.3303.

Minor rotamer had the following distinguishable peaks: 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 5.70 (d, J = 7.8, 1H, H5); 19F NMR (CD3OD): δ −115.82 (dt, J = 13.4, 246.7, 1F).

4-N-(11-Hydroxyundecanyl)-3′,5′-di-O-benzoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (25)

Ammonium cerium (IV) nitrate (63 mg, 0.115 mmol) was added to a solution of 24 (106 mg, 0.145 mmol) in CH3CN:H2O (9:1, 5 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature overnight. Additional portions of CAN (240 mg) were added to the reaction mixture every 24 h until no starting material could be detected by TLC. After 72 h, the reaction was quenched by the addition of saturated NaHSO3 (20 mL), the volatiles evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting aqueous residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 x 20 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (103.5 mg) was then column chromatographed (1% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 25 (66 mg, 70%) as a mixture of rotamers (72:28). The major rotamer had the following peaks: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.24 (br. s, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.51-1.64 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.20 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.63 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.50-4.58 (m, 1H, H4′), 4.64-4.71 (m, 1H, H5′), 4.75-4.82 (m, 1H, H5″), 5.57-5.62 (m, 1H, H3′) 5.60 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.58-6.61 (m, 1H, H1′), 7.31 (“d,” J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.41-7.65 (m, 6H, Ar), 8.02-8.11 (m, 4H, Ar); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 25.79, 26.93, 29.20, 29.29, 29.44, 29.47, 29.53, 29.57, 32.78, 41.14, 62.90, 63.01, 71.86 (m, C3′), 77.74 (C4′), 83.51 (br. s, C1′), 96.55 (C5), 120.98 (t, J = 256.3 Hz, C2′), 128.10, 128.70, 128.81, 129.39, 129.81, 130.27, 133.60, 134.28, 139.86, 155.75, 163.59, 165.05, 166.09; 19F NMR δ −115.36 (dt, J = 13.7, 246.3 Hz, 1F), −120.50 (br. d, 1F); MS (ESI+) m/z 664 (100, [M+Na]+. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C34H41F2N3NaO7 [M+Na]+ 664.2805; found 664.2837.

Minor rotamer had the following distinguishable peaks: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.40-3.41 (m, 2H, CH ), 5.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H5); 19F NMR δ −115.85 (dt, J = 12.4, 246.0 Hz, 1F).

4-N-(11-Fluoroundecanyl)-3′,5′-di-O-benzoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (26)

A chilled (−78 °C) solution of DAST (14 μL, 17.2 mg, 0.107 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (250 μL) was added to a stirred solution of 25 (21.7mg, 0.034 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) at −78 °C. After 30 minutes, the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to ambient temperature and kept stirring. After 3 h, the reaction mixture was poured into a separatory funnel containing a ice-cold solution of Na2HCO3 in H2O (10 mL, pH = 8) and was extracted with CHCl3 (3 x 10 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting oily residue (20.5 mg) was then column chromatographed (40% EtOAc/hexane) to give 26 (10.6 mg, 48%) as a mixture of rotamers (76:24). The major rotamer had the following peaks: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.27 (br. s, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.55-1.69 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.47-3.52 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.43 (dt, J = 6.2, 47.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.51-4.55 (m, 1H, H4′), 4.67 (dd, J = 4.5, 12.3 Hz, 1H, H5′), 4.79 (dd, J = 3.2, 12.3 Hz, 1H, H5″), 5.54 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 5.58-5.63 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.61 (br.s, 1H, H1′), 7.32 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.42-7.66 (m, 6H, Ar), 8.03-8.16 (m, 4H, Ar);13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 25.30, 27.01, 29.24, 29.32, 29.49, 29.56, 29.83, 30.44, 30.63, 41.28, 63.02 (C5′), 71.87 (br. s, C3′), 79.16 (br. s, C4′), 83.56 (br. s, C1′), 84.37 (d, J = 164.0 Hz'), 96.17 (C5), 121.88 (t, J = 255.7 Hz, C2′), 128.14, 128.73, 128.84, 129.43, 129.84, 130.31, 133.59, 134.29, 140.10, 155.46, 163.39, 165.06, 166.10; 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −217.94 (tt, J = 24.9, 47.3 Hz, 1F), −120.62 (br. d, J = 203.1, 1F), −115.40 (dt, J = 14.1, 247.3 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 644 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI-TOF+) m/z calcd for C34H40F3N3NaO6 [M+Na]+ 666.2761; found 666.2763.

Minor rotamer had the following distinguishable peaks: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.20-3.21 (m, 2H, CH N), 5.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H5); 19F NMR δ −115.98 (dt, J = 12.9, 247.5 Hz, 1F)

4-N-(11-Fluoroundecanyl)-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (27)

Method A. Compound 26 (10.6 mg, 0.017 mmol) was dissolved in methanolic ammonia (2 mL) and stirred at ambient temperature. After 2 h, volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was chromatographed (5% MeOH/EtOAc) to give 27 (6.5 mg, 90%) as a clear oil: 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 1.32 (br.s, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.55-1.73 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.78 (dd, J = 3.3, 12.6 Hz, 1H, H5′), 3,87 (dt, J = 3.0, 8.28 Hz, 1H, H3′), 3.93 (‘d’, J = 13.3 Hz, 1H, H5″), 4.20-4.28 (m, 1H, H4′), 4.40 (dt, J = 6.1, 47.6 Hz, 1H, CH2), 5.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 6.21 (“t”, J = 7.96 Hz, H1′), 7.73 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H6); 19F NMR δ −219.94 (tt, J = 25.5, 47.3 Hz, 1F, CH2F), −119.60 (br. s, 1F), −119.14 (br. s, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 436 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C20H32F3N3NaO4 [M+Na]+ 458.2237; found 458.2256.

Method B. In a tightly sealed cylindrical pressure vessel with screw cap, a solution of KF (1.6 mg, 0.028 mmol), K2CO3 (3.8 mg, 0.028 mmol), Kryptofix 2.2.2 (10.5 mg, 0.028 mmol) and 28 (5.0 mg, 0.007 mmol) in CH3CN (1 mL) was stirred at 110 °C. After 18 min, the reaction mixture was quickly cooled in a water bath and vacuum filtrated into another pressure vessel. The effluent containing crude 26 was concentrated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue treated with 0.5 CH3ONa/MeOH (1 mL), then stirred and heated at 100 °C. After 8 min, the reaction mixture was neutralized with 1N HCl and evaporated under reduced pressure to dryness. The crude sample was then dissolved in 45% CH3CN/H2O to a total volume of 4.5 mL, passed through a 0.2 μM PTFE syringe filter and then injected into a semi-preparative HPLC column (Phenomenex Gemini RP-C18 column; 5μ, 25 cm X 1 cm) via 5 mL loop. The HPLC column was eluted with an isocratic mobile phase mixture 45% CH3CN/H2O at a flow rate = 5 mL/min to give 27 (1.9 mg, 62% overall yield from 28, tR = 13.1 min) with spectral properties as above.

4-N-[11-(Methanesulfoxy)undecanyl]-3′,5′-di-O-benzoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine (28)

Et3N (3.8 μL, 2.7 mg, 0.027 mmol) and MsCl (1.5 μL, 2.3 mg, 0.020 mmol) were sequentially added to a stirred solution of 25 (11.6 mg, 0.018 mmol) in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C. After 5 minutes, the reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to ambient temperature and kept stirring. After 3 h, the reaction mixture was then partitioned between H2O and CH2Cl2, and the aqueous layer then extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 x 20 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue (12.1 mg) was column chromatogramphed (50% EtOAc/hexane) to give 28 (11.7 mg, 90%) as a mixture of rotamers (71:29). The major rotamer had the following peaks: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.25 (br.s, 14H, 7 x CH2), 1.55-1.77 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 2.99 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.46-3.52 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.21 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.51-4.58 (m, 1H, H4′), 4.64-4.81 (m, 2H, H5′, H5″), 5.55 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H5), 5.59-5.63 (m, 1H, H3′), 6.55-6.67 (m, 1H, H1′), 7.32 (dd, J = 1.6, 7.5 Hz, 1H, H6), 7.43-7.51 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.57-7.66 (m, 2H, Ar), 8.03-8.10 (m, 4H, Ar); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 21.15, 25.47, 26.94, 29.00, 29.22, 29.30, 29.39, 29.46, 29.55, 37.50, 41.18, 63.02 (C5′), 70.39, 71.96 (“dd,” J = 17.3, 35.8 Hz, C3′), 77.36 (C4′), 84.00 (br. s, C1′), 96.22 (C5), 120.93 (t, J = 262.8 Hz, C2′), 128.13, 128.71, 128.82, 129.41, 129.82, 130.28, 133.61, 134.28, 139.97 (C6), 155.66, 163.55, 165.05, 166.08; 19F NMR δ −120.61 (br.d, J = 261.9 Hz, 1F), −115.38 (dt, J = 14.1, 246.7 Hz, 1F); MS (ESI) m/z 720 (100, [M+H]+); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd for C35H43F2N3NaO9S [M+Na]+ 742.2580; found 742.2603.

Minor rotamer had the following distinguishable peaks: 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 3.23-3.25 (m, CH2N), 5.77 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, H5); 19F NMR δ −115.98 (dt, J = 13.1, 234.1 Hz, 1F).

Cytostatic Activity Assays.33

The compounds tested were added to murine leukemia L1210, human T-lymphocyte CEM, human cervix carcinoma HeLa and human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cell cultures in 96-well microtiter plates. After two (L1210) or three (CEM) or four (HeLa, MCF-7) days incubation at 37°C, the number of living cells was determined by a Coulter counter. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50%.

dCK and TK-2 Activity Assays

The activity of recombinant mitochondrial thymidine kinase (TK-2) and cytosolic 2′-deoxycytidine kinase (dCK), and the 50% inhibitory concentration of the test compounds were assayed in a 50 μL reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM CHAPS, 3 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 2.5 mM ATP, 1 μM [5-3H]dCyd or [CH3-3H]dThd and enzyme. The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in the presence or absence of different concentrations (5-fold dilutions) of the test compounds. Aliquots of 45 μL of the reaction mixtures were spotted on Whatman DE-81 filter paper disks. The filters were washed three times for 5 min each in 1 mM ammonium formate, once for 1 min in water, and once for 5 min in ethanol. The radioactivity retained on the filter discs was determined by scintillation counting. To evaluate substrate activity against TK-2 and dCK, the tested compounds were added to the enzyme reaction mixture at 100 μM and conversion to their 5′-monophosphates was monitored by HPLC on an anion exchange Partisil Sax column.

Human Serum and Murine Liver Extract Stability Assays

The compounds tested were exposed to 50% human serum in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or murine liver extract in PBS at 100 μM concentrations and incubated for 0, 60 and 240 min (human serum) or 0, 30 and 120 min (murine liver extract) at 37 °C. At each time point (0, 60, 240 min) an aliquot was withdrawn and subjected to HPLC analysis on a reverse phase RP-18 column (mobile phase: acetonitrile/H2O). Elution times were 13.2 min and 16.4 min for dFdU and gemcitabine, respectively, and 22.8 min and 22.7 min for compounds 7 and 21, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This investigation was partially supported by award SC1CA138176 from NIGMS and NCI. JP is grateful to MBRS RISE program (NIGMS; R25 GM61347) for his fellowship. The research of JB was supported by the KU Leuven (GOA 10/014). We are grateful to Mrs. Lizette van Berckelaer and Mrs. Ria Van Berwaer for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- dFdC

2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (Gemcitabine)

- hENT1

human equilibrative nucleoside transport protein 1

- dCK

deoxycytidine kinase

- RNR

ribonucleotide reductase

- CTP

cytidine triphosphate

- dFdU

2′,2′-difluorouridine

- CDA

cytidine deaminase

- SQgem

4-N-squalenoylgemcitabine

- [18F]-FAC

1-(2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-β-D-arabinofuranosyl)cytosine)

- L-18F-FMAC

1-(2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-β-L-arabinofuranosyl)-5-methylcytosine

- EDCI

N-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethyl-carbodiimide

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- NMM

N-methylmorpholine

- CDI

1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole

- TEA

triethylamine

- DAST

(diethylamino)sulfur trifluoride

- HDPE

high-density polyethylene

- TK-2

thymidine kinase

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, representative HPLC chromatograms and characterization data for 11-fluoroundecanoic, 11-bromoundecanoyl, 11-aminoundecanol and 11) (benzyloxy)undecan-1-amine. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gesto DS, Cerqueira NM, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. Gemcitabine: a critical nucleoside for cancer therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:1076–1087. doi: 10.2174/092986712799320682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toschi L, Finocchiaro G, Bartolini S, Gioia V, Cappuzzo F. Role of gemcitabine in cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2005;1:7–17. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertel LW, Kroin JS, Misner JW, Tustin JM. Synthesis of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribose and 2-deoxy-2,2′-difluoro-D-ribofuranosyl nucleosides. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:2406–2409. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voutsadakis IA. Molecular predictors of gemcitabine response in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2011;3:153–164. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i11.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramalingam S, Belani C. Systemic chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: recent advances and future directions. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl 1):5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Madiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, VanHoff DD. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: A randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackey JR, Mani RS, Selner M, Mowles D, Young JD, Belt JA, Crawford CR, Cass CE. Functional nucleoside transporters are required for gemcitabine influx and manifestation of toxicity in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4349–4357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinemann V, Hertel LW, Grindey GB, Plunkett W. Comparison of the Cellular Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity of 2′,2′-Difluorodeoxycytidine and 1-β-d-Arabinofuranosylcytosine. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4024–4031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroep JR, van Moorsel CJ, Veerman G, Voorn DA, Schultz RM, Worzalla JF, Tanzer LR, Merriman RL, Pinedo HM, Peters GJ. Role of deoxycytidine kinase (dCK), thymidine kinase 2 (TK2), and deoxycytidine deaminase (dCDA) in the antitumor activity of gemcitabine (dFdC) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;431:657–660. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5381-6_127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Modulatory Activity of 2′,2′-Difluorodeoxycytidine on the Phosphorylation and Cytotoxicity of Arabinosyl Nucleosides. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3675–3680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang P, Chubb S, Hertel LW, Grindey GB, Plunkett W. Action of 2′,2′-Difluorodeoxycytidine on DNA-Synthesis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6110–6117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz van Haperen VWT, Veerman G, Vermorken JB, Peters GJ. 2′,2′-Difluorodeoxycytidine (gemcitabine) incorporation into RNA and DNA of tumour cell lines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:762–766. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90566-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinemann V, Schulz L, Issels RD, Plunkett W. Gemcitabine: a modulator of intracellular nucleotide and deoxynucleotide metabolism. Semin. Oncol. 1995;22:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinemann V, Xu YZ, Chubb S, Sen A, Hertel LW, Grindey GB, Plunkett W. Inhibition of ribonucleotide reduction in CCRF-CEM cells by 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine. Mol. Pharm. 1990;38:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plunkett W, Huang P, Xu Y-Z, Heinemann V, Grunewald R, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: metabolism, mechanisms of action, and self-potentiation. Semin. Oncol. 1995;22:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker CH, Banzon J, Bollinger JM, Stubbe J, Samano V, Robins MJ, Lippert B, Jarvi E, Resvick R. 2′-Deoxy-2′-methylenecytidine and 2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine 5′-diphosphates: potent mechanism-based inhibitors of ribonucleotide reductase. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:1879–1884. doi: 10.1021/jm00110a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva DJ, Stubbe J, Samano V, Robins MJ. Gemcitabine 5 ′-triphosphate is a stoichiometric mechanism-based inhibitor of Lactobacillus leichmannii ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase: Evidence for thiyl radical-mediated nucleotide radical formation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5528–5535. doi: 10.1021/bi972934e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Donk WA, Yu GX, Perez L, Sanchez RJ, Stubbe J, Samano V, Robins MJ. Detection of a new substrate-derived radical during inactivation of ribonucleotide reductase from Escherichia coli by gemcitabine 5 ′-diphosphate. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6419–6426. doi: 10.1021/bi9729357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Artin E, Wang J, Lohman GJS, Yokoyama K, Yu GX, Griffin RG, Bar G, Stubbe J. Insight into the Mechanism of Inactivation of Ribonucleotide Reductase by Gemcitabine 5 ′-Diphosphate in the Presence or Absence of Reductant. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11622–11629. doi: 10.1021/bi901590q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Lohman GJS, Stubbe J. Mechanism of Inactivation of Human Ribonucleotide Reductase with p53R2 by Gemcitabine 5 ′-Diphosphate. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11612–11621. doi: 10.1021/bi901588z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shipley LA, Brown TJ, Cornpropst JD, Hamilton M, Daniels WD, Culp HW. Metabolism and disposition of gemcitabine, and oncolytic deoxycytidine analog, in mice, rats, and dogs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1992;20:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SR, Gandhi V, Jenkins J, Papadopolous N, Burgess MA, Plager C, Plunkett W, Benjamin RS. Phase II clinical investigation of gemcitabine in advanced soft tissue sarcomas and window evaluation of dose rate on gemcitabine triphosphate accumulation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19:3483–3489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandhi V, Plunkett W, Du M, Ayres M, Estey EH. Prolonged infusion of gemcitabine: clinical and pharmacodynamic studies during a phase I trial in relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:665–673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordheim LP, Durantel D, Zoulim F, Dumontet C. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:447–464. doi: 10.1038/nrd4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bender DM, Bao J, Dantzig AH, Diseroad WD, Law KL, Magnus NA, Peterson JA, Perkins EJ, Pu YJ, Reutzel-Edens SM, Remick DM, Starling JJ, Stephenson GA, Vaid RK, Zhang D, McCarthy JR. Synthesis, Crystallization, and Biological Evaluation of an Orally Active Prodrug of Gemcitabine. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6958–6961. doi: 10.1021/jm901181h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couvreur P, Stella B, Reddy LH, Hillaireau H, Dubernet C, Desmaele D, Lepetre-Mouelhi S, Rocco F, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Clayette P, Rosilio V, Marsaud V, Renoir JM, Cattel L. Squalenoyl Nanomedicines as Potential Therapeutics. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2544–2548. doi: 10.1021/nl061942q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasari M, Acharya AP, Kim D, Lee S, Lee S, Rhea J, Molinaro R, Murthy N. H-Gemcitabine: A New Gemcitabine Prodrug for Treating Cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:4–8. doi: 10.1021/bc300095m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Immordino ML, Brusa P, Rocco F, Arpicco S, Ceruti M, Cattel L. Preparation, characterization, cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of liposomes containing lipophilic gemcitabine prodrugs. J. Controlled Release. 2004;100:331–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koolen SL, Witteveen PO, Jansen RS, Langenberg MH, Kronemeijer RH, Nol A, Garcia-Ribas I, Callies S, Benhadji KA, Slapak CA, Beijnen JH, Voest EE, Schellens JH. Phase I study of Oral gemcitabine prodrug (LY2334737) alone and in combination with erlotinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:6071–6082. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pratt SE, Durland-Busbice S, Shepard RL, Heinz-Taheny K, Iversen PW, Dantzig AH. Human Carboxylesterase-2 Hydrolyzes the Prodrug of Gemcitabine (LY2334737) and Confers Prodrug Sensitivity to Cancer Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:1159–1168. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rejiba S, Reddy LH, Bigand C, Parmentier C, Couvreur P, Hajri A. Squalenoyl gemcitabine nanomedicine overcomes the low efficacy of gemcitabine therapy in pancreatic cancer. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2011;7:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickremsinhe E, Bao J, Smith R, Burton R, Dow S, Perkins E. Preclinical Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion of an Oral Amide Prodrug of Gemcitabine Designed to Deliver Prolonged Systemic Exposure. Pharmaceutics. 2013;5:261–276. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics5020261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergman AM, Adema AD, Balzarini J, Bruheim S, Fichtner I, Noordhuis P, Fodstad O, Myhren F, Sandvold ML, Hendriks HR, Peters GJ. Antiproliferative activity, mechanism of action and oral antitumor activity of CP-4126, a fatty acid derivative of gemcitabine, in in vitro and in vivo tumor models. Invest. New Drugs. 2011;29:456–466. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9377-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stuurman FE, Voest EE, Awada A, Witteveen PO, Bergeland T, Hals PA, Rasch W, Schellens JH, Hendlisz A. Phase I study of oral CP-4126, a gemcitabine derivative, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest. New Drugs. 2013;31:959–966. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9925-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maiti S, Park N, Han JH, Jeon HM, Lee JH, Bhuniya S, Kang C, Kim JS. Gemcitabine-Coumarin-Biotin Conjugates: A Target Specific Theranostic Anticancer Prodrug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4567–4572. doi: 10.1021/ja401350x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhuniya S, Lee MH, Jeon HM, Han JH, Lee JH, Park N, Maiti S, Kang C, Kim JS. A fluorescence off-on reporter for real time monitoring of gemcitabine delivery to the cancer cells. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:7141–7143. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42653j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laing RE, Walter MA, Campbell DO, Herschman HR, Satyamurthy N, Phelps ME, Czernin J, Witte ON, Radu CG. Noninvasive prediction of tumor responses to gemcitabine using positron emission tomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:2847–2852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroep JR, Loves WJP, van der Wilt CL, Alvarez E, Talianidis L, Boven E, Braakhuis BJM, van Groeningen CJ, Pinedo HM, Peters GJ. Pretreatment deoxycytidine kinase levels predict in vivo gemcitabine sensitivity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002;1:371–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saiki Y, Yoshino Y, Fujimura H, Manabe T, Kudo Y, Shimada M, Mano N, Nakano T, Lee Y, Shimizu S, Oba S, Fujiwara S, Shimizu H, Chen N, Nezhad ZK, Jin G, Fukushige S, Sunamura M, Ishida M, Motoi F, Egawa S, Unno M, Horii A. DCK is frequently inactivated in acquired gemcitabine-resistant human cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;421:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radu CG, Shu CJ, Nair-Gill E, Shelly SM, Barrio JR, Satyamurthy N, Phelps ME, Witte ON. Molecular imaging of lymphoid organs and immune activation by positron emission tomography with a new [(18)F]-labeled 2 ′-deoxycytidine analog. Nature Med. 2008;14:783–788. doi: 10.1038/nm1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarzenberg J, Radu CG, Benz M, Fueger B, Tran AQ, Phelps ME, Witte ON, Satyamurthy N, Czernin J, Schiepers C. Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of novel PET probes targeting the deoxyribonucleoside salvage pathway. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. I. 2011;38:711–721. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JT, Campbell DO, Satyamurthy N, Czernin J, Radu CG. Stratification of Nucleoside Analog Chemotherapy Using 1-(2 ′-Deoxy-2 ′-F-18-Fluoro-beta-D-Arabinofuranosyl)Cytosine and 1-(2 ′-Deoxy-2 ′-F-18-Fluoro-beta-L-Arabinofuranosyl)-5-Methylcytosine PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2012;53:275–280. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.090407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katritzky AR, Suzuki K, Singh SK. N-acylation in combinatorial chemistry. Arkivoc. 2004:12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinha ND, Davis P, Schultze LM, Upadhya K. A simple method for N-acylation of adenosine and cytidine nucleosides using carboxylic acids activated In-Situ with carbonyldiimidazole. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:9277–9280. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu XF, Williams HJ, Scott AI. An improved transient method for the synthesis of N-benzoylated nucleosides. Synth. Commun. 2003;33:1233–1243. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo ZW, Gallo JM. Selective protection of 2 ′,2 ′-difluorodeoxycytidine (gemcitabine) J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8319–8322. doi: 10.1021/jo9911140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hugenberg V, Wagner S, Kopka K, Schober O, Schafers M, Haufe G. Synthesis of geminal difluorides by oxidative desulfurization-difluorination of alkyl aryl thioethers with halonium electrophiles in the presence of fluorinating reagents and its application for 18F-radiolabeling. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:6086–6095. doi: 10.1021/jo100689v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bucsi I, Torok B, Marco AI, Rasul G, Prakash GK, Olah GA. Stable dialkyl ether/poly(hydrogen fluoride) complexes: dimethyl ether/poly(hydrogen fluoride), a new, convenient, and effective fluorinating agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7728–7736. doi: 10.1021/ja0124109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang T, Neumann CN, Ritter T. Introduction of Fluorine and Fluorine-Containing Functional Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2013;52:8214–8264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hertel LW, Kroin JS. 2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-(4-substituted pyrimidine) nucleosides having antiviral and anti-cancer activity and intermediates. Eur. Pat. Appl. 1993:576230. The 4-N-alkyl substituted gemcitabine derivatives are reported as cytotoxic with IC50 values in the μM range. For original preparation of 4-N-alkyl substituted gemcitabine derivatives and cytotoxic evalutaion in CCRF-CEM cell line: [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krajewska E, Shugar D. Alkylated cytosine nucleosides: substrate and inhibitor properties in enzymatic deamination. Acta. Biochim. Pol. 1975;22:185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hermida SAS, Possari EPM, Souza DB, Campos IPD, Gomes OF, Di Mascio P, Medeiros MHG, Loureiro APM. 2′-Deoxyguanosine, 2′-deoxycytidine, and 2 ′-deoxyadenosine adducts resulting from the reaction of tetrahydrofuran with DNA bases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:927–936. doi: 10.1021/tx060033d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang XJ, Dmochowski IJ. Phototriggering of caged fluorescent oligodeoxynucleotides. Org. Lett. 2005;7:279–282. doi: 10.1021/ol047729n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plitta B, Adamska E, Giel-Pietraszuk M, Fedoruk-Wyszomirska A, Naskret-Barciszewska M, Markiewicz WT, Barciszewski J. New cytosine derivatives as inhibitors of DNA methylation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kraszewski A, Delort AM, Teoule R. Synthesis of 4-mono-and dialkyl-2′-deoxycytidines and their insertion into an oligonucleotide. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:861–864. [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeGrado TR, Bhattacharyya F, Pandey MK, Belanger AP, Wang SY. Synthesis and Preliminary Evaluation of 18-F-18-Fluoro-4-Thia-Oleate as a PET Probe of Fatty Acid Oxidation. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:1310–1317. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.074245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.