Summary

OBJECTIVE

To investigate the effects of nutritional supplementation on the outcome and nutritional status of south Indian patients with tuberculosis (TB) with and without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection on anti-tuberculous therapy.

METHOD

Randomized controlled trial on the effect of a locally prepared cereal–lentil mixture providing 930 kcal and a multivitamin micronutrient supplement during anti-tuberculous therapy in 81 newly diagnosed TB alone and 22 TB–HIV-coinfected patients, among whom 51 received and 52 did not receive the supplement. The primary outcome evaluated at completion of TB therapy was outcome of TB treatment, as classified by the national programme. Secondary outcomes were body composition, compliance and condition on follow-up 1 year after cessation of TB therapy and supplementation.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference in TB outcomes at the end of treatment, but HIV–TB coinfected individuals had four times greater odds of poor outcome than those with TB alone. Among patients with TB, 1/35 (2.9%) supplemented and 5/42(12%) of those not supplemented had poor outcomes, while among TB–HIV-coinfected individuals, 4/13 (31%) supplemented and 3/7 (42.8%) non-supplemented patients had poor outcomes at the end of treatment, and the differences were more marked after 1 year of follow-up. Although there was some trend of benefit for both TB alone and TB–HIV coinfection, the results were not statistically significant at the end of TB treatment, possibly because of limited sample size.

CONCLUSION

Nutritional supplements in patients are a potentially feasible, low-cost intervention, which could impact patients with TB and TB–HIV. The public health importance of these diseases in resource-limited settings suggests the need for large, multi-centre randomized control trials on nutritional supplementation.

Keywords: nutritional supplementation, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, nutrition, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading cause of illness and death of people globally. In 2008, WHO reported that there were an estimated 9.4 million incident cases of TB globally, equivalent to 139 cases per 100 000 population. Most cases occurred in Asia (55%) and Africa (30%) (WHO 2009). Almost one in four of the world's 2 million AIDS-related deaths each year is associated with TB. The majority of these deaths occur in Africa, where the TB mortality rate in people living with HIV is more than 20 times higher than in the rest of the world (WHO 2010). Compared with those who are not infected with HIV, a person infected with HIV has a tenfold risk of developing TB. TB has increased in populations where both HIV infection and M. tuberculosis infection are common, with some parts of sub-Saharan Africa seeing a three- to fivefold increase in the number of TB cases since the early 1990s (WHO 2004).

The interactions between TB and malnutrition have been studied in both Asia and Africa, in settings where TB, malnutrition and HIV are major health problems (Niyongabo et al. 1999; Gupta et al. 2009; Lönnroth et al. 2009). Progressive tuberculous disease results in wasting and loss of muscle mass and hypoalbuminaemia, which are also seen in HIV infection, and the occurrence of TB–HIV coinfection results in a greater decrease in body mass and fat mass than either infection alone (Shah et al. 2001). A recent report from India, on the nutritional status of HIV-infected individuals with and without TB, showed that malnutrition, anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia were most pronounced among TB–HIV-coinfected patients with weight loss associated with loss of fat in women and with loss of body cell mass in men (Swaminathan et al. 2008).

A recent Cochrane systematic review by Abba et al. (2008), which examined nutritional supplements for patients with TB, found limited evidence that high-energy supplements and some combinations of zinc with other micronutrients might help patients with tuberculosis to gain weight. There was not enough evidence to assess the effect of other combinations of nutrients. Therefore, there is a need for well-conducted studies for evidence-based design of potential interventions to improve nutritional status and other treatment-related outcomes. While a recent study from Dili found no benefit for improved adherence to anti-TB therapy (Martins et al. 2009), this is also an area that could be explored further.

As malnutrition can lead to energy and micronutrient deficiencies, we conducted a pilot open-labelled randomized controlled trial on the effect of macro- and micronutrient supplementation during anti-tuberculous therapy in patients with TB with and without HIV to provide baseline data for the design of interventions to promote nutritional status and treatment outcomes.

Methods

The study was carried out with newly diagnosed patients starting directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) therapy at one of four clinics in Vellore town in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The guidelines of the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme were followed for diagnosis, therapy, follow-up and assessment of outcome of treatment (2005) for all patients. Candidates for inclusion were patients aged >12 years, who were either sputum positive for acid-fast bacilli or sputum negative but with clinical and radiological evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis or culture- and/or biopsy-proven extra pulmonary tuberculosis. Patients who had relapsed, end-stage renal or liver disease, CD4 counts >200 (among the HIV positive), body mass index (BMI) >19, patients not from outside Vellore district or not willing to give written informed consent to participate, were excluded. Participants were recruited between January and November 2005.

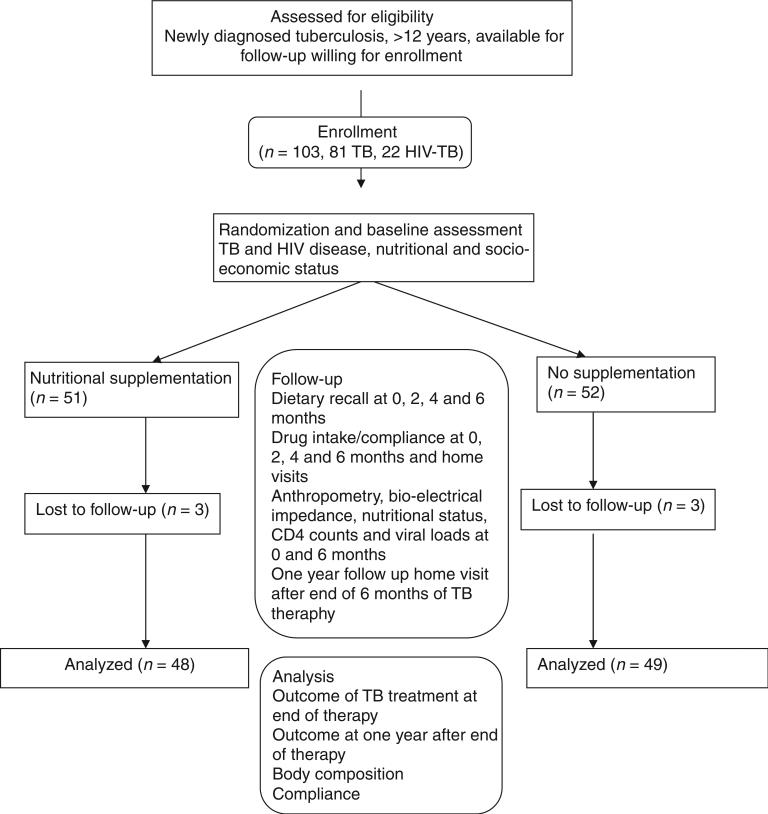

All patients received anti-tuberculous therapy (ATT) under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (2005). The chemotherapy regimen is determined by the patient category according to the RNTCP-DOTS programme, and all patients belonged to Categories I or III and were therefore treated with either the 2H3R3Z3E3 + 4H3R3 regimen or 2H3R3Z3 + 4H3R3 where H: Isoniazid (600 mg), R: Rifampicin (450 mg), Z: Pyrazinamide (1500 mg) and E: Ethambutol (1200 mg). These regimens require a 2-month intensive phase with daily attendance at the DOTS clinic followed by a 4-month continuation phase with monthly visits to the clinic. All study participants were followed up at the DOTS clinic at screening, recruitment, 2, 4, 5 and 6 months (Figure 1) and visited at home 1 year after completion of therapy to identify relapses. Sputum acid fast bacilli (AFB) data were collected at baseline and 5 months.

Figure 1.

Trial design for the open-labelled randomized trial of macronutrient and micronutrient supplementation during anti-tuberculous therapy in patients with tuberculosis or tuberculosis and HIV.

After discussion of the study and the informed consent process, all participants provided demographic data and socioeconomic status assessed by a modified Kuppuswami (1981), underwent HIV testing and had haemograms, liver and renal function tests, including serum albumin, sputum AFB smears and cultures. All HIV-positive participants had CD4 count (Flow Cytometer Haematology Analyser; Guava Technologies Inc, Hayward, CA, USA) and HIV RNA viral load assessment (Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test, Version 1.5; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). At entry, height, weight, skin fold thicknesses (triceps, subscapular and suprailiac) and mid-arm circumference measurements were recorded, along with evaluations by bioimpedance analysis (BIA; Quantum hand held analyzer-RJL systems Inc, Detroit, MI, USA) for reactance and resistance, which were used to calculate body composition, lean body mass and body fat, based on the equations of Lukaski (1989) and adjusted appropriately (Kotler et al. 1996). Anthropometric data were used to calculate the body mass index (BMI). After 6 months, at the end of anti-TB therapy, all tests were repeated.

After study inclusion and baseline assessment, all participants were evaluated by a dietician who took detailed dietary histories (24 h and 3-month diet recall) and advised them on an appropriate diet. Participants were randomized to receive a nutritional supplement plus standard of care or standard of care alone by a computer-generated randomization code. Randomization was stratified for HIV status only. Allocation was concealed; the randomization codes were in opaque envelopes opened by the dietician after dietary counselling was completed. There were no attempts made to blind any of the study team or participants. At the 2-, 4- and 6-month visits, a 24-h dietary recall was recorded, and the proportions of carbohydrates, proteins, fats and micronutrients were calculated by a dietician based on the food tables of the National Institute for Nutrition, India (Gopalan et al. 1989).

The macronutrient supplement was based on Indian requirements (Indian Council for Medical Research, 1990) as calculated by the study dietician, prepared as a ready-to-serve powder tested for palatability by the study team. The macronutrient supplement was a cereal and lentil mixture prepared in the Dietary Department of the hospital, each serving of which contained 25 g roasted wheat, 15 g roasted groundnut, 15 g roasted Bengal gram and 15 g jaggery. Three servings a day were calculated to provide 930 kcal and 31.5 g protein. The micronutrient supplement was a one-a-day multivitamin tablet (Multivite FM- Universal Medicare, Mumbai, India), which contained copper sulphate 0.1 mg, D-panthenol 1 mg, dibasic calcium phosphate 35 mg, folic acid 500 μg, magnesium oxide 0.15 mg, manganese sulphate 0.01 mg, nicotinamide 25 mg, potassium iodide 0.025 mg, vitamin A 5000 iu, vitamin B1 2.5 mg, vitamin B12 2.5 μg, vitamin B2 2.5 mg, vitamin B6 2.5 mg, vitamin C 40 mg, vitamin D3 200 iu, vitamin E 7.5 mg and zinc sulphate 50 mg (Table 1). Participants were given enough supplement for 1 month at a time, with three sachets making up one daily supplement. The period of supplementation was the 6-month period of ATT under the national programme. Compliance with nutritional supplementation was checked by review by the dietician and by random home visits by a field worker (up to 2–3 visits) who counted remaining sachets and enquired about their use. Compliance with use of anti-TB medication was measured on a 7-point scale, where one was excellent and seven was poor compliance.

Table 1.

Nutritive values of the macronutrient and micronutrient supplement used as an intervention for patients with tuberculosis or tuberculosis and HIV during the period of anti-tuberculous therapy compared to the recommended daily allowance for adults

| Nutrient | Supplement composition | Recommended daily allowance* |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | 930 kcal | 2730 kcal |

| Proteins | 31.5 g | 60 g |

| Vitamin A | 125 μg | 600 μg |

| Vitamin B1 | 2.5 mg | 1.4 mg |

| Vitamin B2 | 2.5 mg | 1.6 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 2.5 mg | 2.0 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 2.5 μg | 1 μg |

| Vitamin C | 40 mg | 40 mg |

| Vitamin D3 | 200 iu | 200 iu |

| Folic Acid | 500 μg | 200 μg |

| Magnesium | 0.01 mg | 340 mg |

| Zinc | 50 mg | 12 mg |

| Calcium | 35 mg | 600 mg |

Based on the Indian Council for Medical Research (1990).

The primary outcome assessed was TB treatment outcome at the end of ATT. For TB, the RNTCP categories of cure, completion of treatment, failure of treatment, interruption of treatment, loss to follow-up or death were considered good outcomes for the first two categories, and the rest were poor outcomes, as shown in Table 1(Revised National TB Control Programme 2005). The secondary outcome measures were body composition, compliance and outcome 1 year after ATT.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and analysed with SPSS for Windows, Rel. 15.0.1. 2007. Chicago: SPSS Inc. Statistical testing was carried out using Pearson chi-square and Fischer's exact test. For comparing means of normally distributed variables, the T test was applied. Normality and equal variance assumptions were tested and found to hold.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Christian Medical College, Vellore, and the trial was retrospectively registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2010/091/006112).

Results

A total of 103 patients with TB meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited. Of these, 81 had TB alone and 22 were TB–HIV coinfected, and 51 received and 52 did not receive the supplement. At baseline, there were no significant differences between the supplemented and non-supplemented groups in age, gender, BMI, serum albumin, body fat, lean body mass and recorded calorie, protein and fat intake (Table 2), although despite randomization, the supplemented group had poorer initial nutritional status, as measured by most parameters. The patients belonged mainly to the lower socioeconomic strata. Most patients had only preschool education, and their families earned between Rs 500 and 1000. TB–HIV-coinfected patients were poorer.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with tuberculosis (TB) and TB–HIV coinfection enrolled in an open-labelled, randomized controlled trial of macro- and micronutrient supplementation during directly observed short-course chemotherapy for TB

| Parameter | Supplement | No supplement |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 51 | 52 |

| Age in years | 36.8 | 37.8 |

| Male Gender, No. (%) | 31 (60.8) | 32 (62.7) |

| Seropositive for HIV, No. (%) | 13 (25.5) | 9 (17.3) |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 17.2 | 18.2 |

| Albumin g/dl | 3.26 | 3.5 |

| Body fat at entry (%) | 9.2 | 13.02 |

| Lean body mass at entry (kg) | 38.1 | 38.3 |

| Calorie intake at entry (kcal) | 2129 | 2072 |

| Protein intake at entry (g) | 54 | 52.3 |

| Fat intake at entry (g) | 34.1 | 36.2 |

| CD4 counts/mm3 at entry (mean) | 168 | 146 |

| HIV Viral load/ml Initial (median) | 595 715.5 | 1 018 998 |

At completion of ATT and 6 months of supplementation, 48 participants remained in the supplemented arm and 49 in the non-supplemented group (Figure 1). The reasons for non-completion of the study were either loss to follow-up or the subject moving out of the study area. On comparison of TB–HIV patients with those with TB alone, the odds ratio of a poor outcome at completion of TB therapy was 4.06 (0.93–17.8) in coinfected individuals. As can be seen from Table 3, among HIV-negative TB patients, 1/35 supplemented patients had a poor outcome whereas 5/42 of the non-supplemented group did, giving an odds ratio (95% CI) of 4.59 (0.51–41.34). In TB-HIV-coinfected individuals, 4/13 of the supplemented group and 3/7 of the non-supplemented group had poor outcomes at the end of TB treatment, OR 1.68 (0.25–11.34). Although there is some evidence of possible benefit for TB patients with and without HIV, the results are not statistically significant, possibly because of the limited sample size. The Mantel Haenszel's pooled OR (CI) was 2.78 (0.7–11.1). χ2 test for homogeneity (M-H) was 0.465 (P = 0.496). A binary logistic regression model incorporating age ≥35, BMI ≥ 16 at baseline and HIV status had an adjusted OR (CI) of 2.81 (0.68–11.53) for supplementation resulting in good outcome.

Table 3.

Outcome of short-course chemotherapy according to the Revised National Tuberculosis Programme in patients with tuberculosis (TB) alone and TB–HIV randomized to receive or not receive micro- and macronutrient supplementation during anti-tuberculous therapy (ATT)

| Disease status | Supplementation status | Good outcome* | Poor outcome† | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At completion of ATT | ||||

| TB+/HIV− | Supplemented | 34 | 1 | 4.59 (0.51–41.34) |

| Not supplemented | 37 | 5 | ||

| TB+/HIV+ | Supplemented | 9 | 4 | 1.68 (0.25–11.34) |

| Not supplemented | 4 | 3 | ||

| 1 year after completion of ATT | ||||

| TB+/HIV− | Supplemented | 22 | 9 | 0.84 (0.29–2.43) |

| Not supplemented | 29 | 10 | ||

| TB+/HIV+ | Supplemented | 6 | 7 | 6.86 (0.66–71.7) |

| Not supplemented | 1 | 8 | ||

Good outcome included those who were designated under RNTCP as Cured (pulmonary smear-positive, completed treatment and had negative smear results on two occasions, one of which is at the end of treatment) or Treatment completed (i) Either pulmonary smear-positive, completed treatment with negative smears at the end of the intensive phase but none at the end of treatment or (ii) pulmonary smear-negative or extrapulmonary and completed treatment.

Poor outcomes included Failure (i) pulmonary smear-positive Category I and was smear positive at 5 months or later, (ii) pulmonary smear-positive Category II (retreatment) and was smear positive at 5 months or later of Category II treatment or pulmonary smear negative or (iii) extrapulmonary on Category III, but was smear positive any time during treatment. Default (not taken drugs for more than 2 months consecutively any time after starting treatment), Death (died from any cause whatsoever while on treatment). Relapse (declared cured or treatment completed, but reports back to the health service and is now found to be sputum smear positive). Six subjects were lost to follow up at the end of treatment, and data for 11 were not available at 1 year.

The initial and 6-month mean (SD) CD4 count and median viral loads in the supplemented group were 168 (174) and 221 (142) (132% increase) and 595 715 and 845 819 (142% increase), respectively. The initial and 6-month mean (SD) CD4 count and median viral loads in the non-supplemented group were 146 (125) and 249 (387) (164% increase) and 1 018 998 and 1 435 700 (141% increase), respectively. Overall, CD4 counts and viral loads increased in both groups.

Supplementation resulted in a statistically significant increase in caloric intake, proteins and fats in the supplemented group. However, the overall caloric increase was about 110 kcal, despite the provision of 930 kcal, and the good compliance with both ATT and the supplementation. The intake in the non-supplemented group declined by 370 kcal even though they also gained lean body mass (Table 4), although to a lesser extent than the supplemented group. When patients with good outcome were compared with those with poor outcomes, it was interesting to note that the patients with good outcomes had gained 1.2 kg more lean body mass over the 6-month follow-up regardless of supplementation, and patients with poor outcomes had greater reductions in caloric, protein and fat intake (data not shown). Patients with poor outcome also had lower albumin levels (mean 2.4 g/dl) at baseline, raising the possibility that this could be a useful prognostic marker for these patients. However, albumin levels increased in both supplemented and non-supplemented groups and were not significantly different at the end of 6 months.

Table 4.

Effect of micro- and macronutrient supplementation on intake and nutritional parameters after 6 months of supplementation in patients with tuberculosis (TB) alone and TB–HIV randomized to receive or not receive micro- and macronutrient supplementation during anti-tuberculous therapy

| Parameter | With supplement Mean (SEM) N = 44 | No supplement Mean (SEM) N = 41 | Significance P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in Hb (mg/dl) | 1.07 (0.39) | 0.585 (0.25) | 0.292 |

| Change in Calories/day (kcal) | 11.15 (133) | –375.42 (139.5) | 0.050 |

| Change in carbohydrate intake (g/day) | 14.54 (28.5) | –53.20 (26.43) | 0.324 |

| Change in protein intake (g/day) | 4.6 (4.4) | –9.85 (4.05) | 0.019 |

| Change in fat intake (g/day) | 2.86 (2.85) | –10.78 (2.67) | 0.009 |

| Change in lean body mass (kg) | 2.37 (0.75) | 2.40 (0.98) | 0.479 |

| Change in body fat (kg) | 1.72 (0.73) | 1.10 (0.85) | 0.573 |

The change refers to the mean difference in each parameter between the last and first visits during anti-tuberculous therapy.

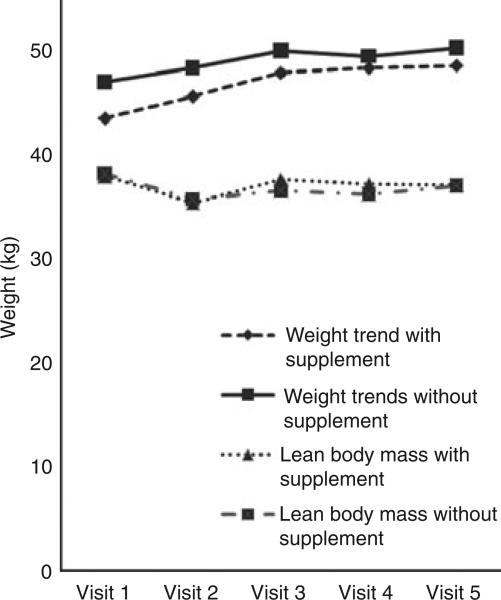

The dietary follow-up showed that calorie, fat and protein intake all decreased in both groups over the first 2 months of follow-up and then increased to approximately baseline in the supplemented group and increased but remained below baseline in the non-supplemented group (data not shown). Measurements of weight showed that weight increased steadily over the follow-up period, although lean body mass declined for the first 2 months and then increased in both the supplemented and the non-supplemented group (Figure 2), while body fat increase paralleled the weight increase. As seen in Table 4, there was an increase in haemoglobin concentration, total calorie, carbohydrate, protein and fats in the supplemented arm. Surprisingly, there was a decrease in all dietary intake parameters in non-supplemented patients.

Figure 2.

Mean weight and lean body mass in patients with tuberculosis (TB) and TB–HIV who did and did not receive supplementation during 6 months of anti-tuberculous chemotherapy. Patients were assessed at 0, 2, 4, 5 and 6 months. HIV-coinfected individuals were treated for TB, but did not receive antiretroviral therapy, as per protocol in India at the time.

Compliance with ATT was good, but fell in the non-supplemented group towards the end of the study. The overall compliance was 1.12, with 1 as the best possible score, with no statistically significant differences with supplementation (P = 0.197). Compliance with dietary supplementation was also excellent (mean 1.24), and a narrowing of the range indicating better compliance was seen towards the end of the study (individual data not shown).

Participants were also followed up for TB status 1 year post-completion of therapy, when data were obtained for 92 (94.8%) of 97 individuals. Nineteen of 70 patients with TB had poor outcomes, as did 15 of 22 TB–HIV patients (Table 3). The OR (CI) of a non-supplemented TB–HIV patient having a poor outcome at 1 year was 6.86 (0.66–71.7). Overall, 22 patients had died, and two had relapse of TB.

Discussion

This small pilot randomized controlled trial on nutritional supplements for patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB with or without HIV coinfection has demonstrated some improvement in outcome and improved nutritional status, which was more marked in patients with TB–HIV coinfection. This study was not sufficiently powered to demonstrate statistically significant benefit, but does provide a basis for developing larger-scale trials of nutritional supplementation in developing countries.

Compliance with the supplement was high. The study excluded those with a BMI > 19 and high CD4 counts to focus on those most likely to benefit from supplementation. Despite randomization, the supplemented group appeared slightly more malnourished at baseline. However, there appears to be no other difference in the two groups with regard to all other important baseline characteristics. As expected, coinfection with HIV resulted in a much higher rate, about four times increased odds, of poor outcomes at the end of TB treatment. A very striking finding is the marked difference in outcome at 1 year between the supplemented and non-supplemented groups (Table 3), with little or no difference in the TB alone group, but a large difference in poor outcomes in TB–HIV patients with 7/13 (53%) of the supplemented patients having poor outcomes, but 8/9 (88.9%) of those not receiving supplement, although the results are not significant, possibly because of the small number of coinfected patients. These results should be interpreted with caution because only patients with CD4 counts <200 and with low BMIs were included.

The 110 kcal increase in the supplemented arm, despite the delivery of 930 kcal, could be because either the patients reduced intake of other food or shared the supplement with other family members. It appears from the increase in lean body mass and haemoglobin that the former is more likely. The ingestion of the first sachet of the supplement for each day was supervised for the first 2 months during the intensive phase of ATT. Despite this, the nutritional intake of calories, protein and fat declined in both supplemented and non-supplemented groups for about 6 weeks followed by a gradual increase, mirrored by the lean body mass, but not by weight and body fat, which increased once therapy started. This early decreased intake could be explained by anorexia, because of either the disease process or the side effects of the medications, during the early intensive phase of therapy.

The increase in body fat reflects the trend seen in re-feeding in other diseases, such as HIV (Miller 1999). Because the lean body mass and body fat measures were calculated from the BIA, it is possible that shifts in body water could account for these trends, although care was taken to assess peripheral oedema. However, the patterns for dietary parameters, weight, lean body mass and body fat, when viewed together, suggest that these trends are not measurement artefacts.

Poor outcomes appeared to be associated with less weight gain and lower albumin levels at baseline, and it is possible that albumin levels could serve as an indicator for intensive nutritional support and monitoring.

No previous studies have combined supplementation with both macro- and micronutrients. In tuberculosis, subjects receiving better nutrition tend to show more rapid clearance of bacteria, resolution of radiographic changes and greater weight gain, although cure rates were similar to those with poorer nutrition (Karyadi et al. 2002a). Micronutrient supplementation benefits diverse populations, including those with HIV who have slower progression of disease (Karyadi et al. 2002b; Fawzi et al. 2004) and TB with a report of increased efficacy of anti-tuberculosis treatment, greater weight gain although without significant effects on culture conversion (Range et al. 2005) and an initial improvement in iron indices but no difference in clinical or radiological disease activity (Das et al. 2003). A high-energy supplement study on patients with TB found an early increase in lean body mass followed by an increase in body fat (Paton et al. 2004).

The 1-year outcomes seem to suggest that outcomes for TB are worse than those recorded by the RNTCP. The 13/97 (13.3%) overall poor outcome at 6 months becomes 34/92 (37.0%) at 1-year follow-up, and the difference is even more stark in the HIV–TB patients with 1-year outcomes being poor in nearly 89% among those who had not received supplements. Encouragingly, the supplemented subgroup of the HIV–TB coinfected had 54% poor outcomes at the 1-year follow-up. Whilst these are small numbers, they suggest that outcomes for TB need follow-up beyond the duration of treatment. It also appears that the benefit of supplementation may be more in the HIV-coinfected subgroup of patients with TB, and this benefit extends beyond the duration of supplementation and TB treatment.

Nutritional supplements in patients are a feasible, low-cost intervention which could have a significant impact by improving cure rates and the immune status of patients with TB and HIV–TB, both during and after anti-tuberculous therapy. The public health importance of these diseases in resource-limited settings suggest that there is a need for a large, multicentre randomized control trial on the role of nutritional supplementation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported the Fogarty AIDS International Research and Training Program D43TW000237 and the Global Infectious Disease Research Training grant D43TW007392.

References

- Abba K, Sudarsanam TD, Grobler L, Volmink J. Nutritional supplements for people being treated for active tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2008;4:CD006086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006086.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das BS, Devi U, Mohan Rao C, Srivastava VK, Rath PK, Das BS. Effect of iron supplementation on mild to moderate anaemia in pulmonary tuberculosis. British Journal of Nutrition. 2003;90:541–550. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, et al. A randomized trial of multivitamin supplements and HIV disease progression and mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:23–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan C, Rama Sastri BV, Balasubramanian SC, Narasinga Rao BS, Deosthale YG, Pant KC. Nutritive Value of Indian Foods. 2nd edn. National Institute of Nutrition; Hyderabad: 1989. revised and updated by. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KB, Gupta R, Atreja A, Verma M, Vishvkarma S. Tuberculosis and nutrition. Lung India. 2009;26:9–16. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.45198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council for Medical Research . Nutrient Requirements & Recommended Dietary Allowances for Indians. Indian Council for Medical Research; New Delhi: 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi E, West CE, Nelwan RHH, Dolmans WMV, Schultink JW, van der Meer JWM. Social aspects of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Indonesia. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine & Public Health. 2002a;33:338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi E, West CE, Schultink W, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vitamin A and zinc supplementation in persons with tuberculosis in Indonesia: effects on clinical response and nutritional status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002b;75:720–727. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler DP, Burastero S, Wang J, Pierson RN. Prediction of body cell mass, fat-free mass, and total body water with bioelectrical impedance analysis: effects of race, sex, and disease. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;64(Suppl. 3):489S–497S. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppuswami B. Manual of Socioeconomic Scale. Manasayan; New Delhi: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:2240–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaski H. Use of bioelectric impedance analysis to assess human body composition. In: Livingstone GE, editor. Nutritional Assessment of an Individual. Food and Nutrition Press; Trumbull, CT: 1989. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Martins N, Morris P, Kelly PM. Food incentives to improve completion of tuberculosis treatment: randomised controlled trial in Dili, Timor-Leste. British Medical Journal. 2009;339:b4248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T. Nutritional Aspects of HIV Infection. Oxford University Press; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Niyongabo T, Henzel D, Idi M, et al. Tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and malnutrition in Burundi. Nutrition. 1999;15:289–293. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton NI, Chua Y, Earnest A, Chee CBE. Randomized controlled trial of nutritional supplementation in patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis and wasting. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80:460–465. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range N, Andersen AB, Magnussen P, Mugomela A, Friis H. The effect of micronutrient supplementation on treatment outcome in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a randomized controlled trial in Mwanza, Tanzania. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2005;10:826–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revised National TB Control Programme . Technical and Operational Guidelines for Tuberculosis Control. Central TB Division. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; New Delhi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Whalen C, Kotler DP, et al. Severity of human immunodeficiency virus infection is associated with decreased phase angle, fat mass and body cell mass in adults with pulmonary tuberculosis infection in Uganda. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:2843–2847. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan S, Padmapriyadarsini C, Sukumar B, et al. Nutritional status of persons with HIV infection, persons with HIV infection and tuberculosis, and HIV-negative individuals from southern India. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:946–949. doi: 10.1086/528860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization TB/HIV Clinical manual. 2004 WHO/HTM/TB/2004.329. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Global tuberculosis control: a short update to the 2009 report. 2009 WHO/HTM/TB/2009.426. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. 2010 http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/tb/9789241500708/