Abstract

TRF1 is part of the shelterin complex, which binds telomeres and it is essential for their protection. Ablation of TRF1 induces sister telomere fusions and aberrant numbers of telomeric signals associated with telomere fragility. Dyskeratosis congenita is characterized by a mucocutaneous triad, bone marrow failure (BMF), and presence of short telomeres because of mutations in telomerase. A subset of patients, however, show mutations in the shelterin component TIN2, a TRF1-interacting protein, presenting a more severe phenotype and presence of very short telomeres despite normal telomerase activity. Allelic variations in TRF1 have been found associated with BMF. To address a possible role for TRF1 dysfunction in BMF, here we generated a mouse model with conditional TRF1 deletion in the hematopoietic system. Chronic TRF1 deletion results in increased DNA damage and cellular senescence, but not increased apoptosis, in BM progenitor cells, leading to severe aplasia. Importantly, increased compensatory proliferation of BM stem cells is associated with rapid telomere shortening and further increase in senescent cells in vivo, providing a mechanism for the very short telomeres of human patients with mutations in the shelterin TIN2. Together, these results represent proof of principle that mutations in TRF1 lead to the main clinical features of BMF.

Introduction

Telomeres consist of tandem TTAGGG repeats and associated proteins that form a capping structure at the ends of chromosomes, protecting them from DNA repair activities and from degradation1,2. The length of telomeric repeats is mainly regulated by enzyme telomerase, which can add telomeric repeats de novo at chromosome ends because of its reverse transcriptase (TERT) activity that uses an associated RNA component (TERC) as template3,4. Telomere repeats are then bound by a 6-protein complex, known as shelterin, encompassing TIN2, TRF1, TRF2, TPP1, POT1, and RAP1, which is needed to form a functional telomere2,3,5. TRF1, together with POT1 and TRF2, directly binds telomeric DNA2,3,5. TRF1 has been proposed to have roles in the regulation of telomere length and telomere capping, as well as in the prevention of replication fork stalling at telomeres1–3,5. TRF1 ablation leads to rapid cellular senescence because of activation of DNA damage response (DDR) 6,7, supporting an essential role of TRF1 in preventing DNA damage at telomeres.

Dyskeratosis congenita (DKC) is considered to be paradigmatic of premature aging syndromes and it is characterized by the classic triad of bone marrow failure (BMF), skin abnormalities, and increased risk of cancer8,9. The molecular basis of DKC commonly involves mutations in genes related to telomere maintenance8–10. Disturbance of telomere maintenance results in premature telomere shortening and subsequent replicative senescence, leading to premature stem cell exhaustion and tissue failure11. The most frequent DKC mutations affect the telomerase complex, including the telomerase RNA component or TERC and the reverse transcriptase subunit or TERT, as well as small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins important for the stability of TERC, such as DKC1, NHP2, or NOP10, and therefore for proper functioning of telomerase10,12,13. In addition, mutations of the shelterin protein TIN2 contribute to approximately 10%-20% of all DKC cases10,12,13. TIN2 mutations are autosomal-dominant and generally de novo mutations in contrast to mutations in components of the telomerase complex8–10.

Concerning the clinical manifestations of DKC, patients with mutations in TIN2 appear to have more clinical features and a more severe clinical course than those with mutations in telomerase10,14,15. Furthermore, the onset of the disease develops at a younger age in patients with TIN2 mutations compared with patients with telomerase mutations15–17. Strikingly, patients with TIN2 mutations are characterized by presence of very short telomeres, a feature that correlates with the severity of the disease and that it is used to identify these patients versus other BMF syndromes10,14–16,18. In contrast to mutations affecting the telomerase complex, the mechanism underlying the dramatic telomere shortening associated with TIN2 mutations remains presently unknown. Of note, all known TIN2 mutations in patients with DKC are found in exon 6, in the proximity of the TRF1 binding site18,19, raising the interesting possibility that impaired interaction of TRF1 and TIN2 can contribute to the severe DKC phenotype. In line with this hypothesis, deletion of the TRF1 binding site of TIN2 results in reduced in vitro TRF1 levels in the shelterin complex20–23. Further supporting a potential involvement of TRF1 in the pathogenesis of DKC, allelic variations in TRF1 have been associated with BMF24,25. However, solid proof that TRF1 mutations can cause BMF is still pending.

In the present study, we set out to test whether abrogation of TRF1 in the hematopoietic system can recapitulate the clinical features of BMF. To this end, we generated a conditional TRF1 deletion mouse model for the hematopoietic system. Our results in vivo demonstrate that deletion of TRF1 results in BMF. In addition, we were able to reproduce the main clinical features as observed in DKC patients with TIN2 mutations, such as severe telomere shortening over time, reduced progenitor cells, and progressive development of cytopenia and BMF. In summary, we describe the first mouse model simulating DKC features caused by alteration of the TRF1 shelterin component. Our results also provide the first mechanistic explanation for the severe telomere shortening in the in vivo setting of the bone marrow associated with shelterin mutations in patients with DKC.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

TRF1flox/flox mice were generated in our laboratory as described6. To conditionally delete TRF1 in the bone marrow, homozygous TRF1flox/flox mice were crossed with transgenic mice expressing Cre under the control of the endogenous Mx1 promotor (Mx1-Cre) 26. Heterozygous TRF1flox/wt Mx1-Cre mice were crossed with homozygous TRF1flox/flox mice to obtain TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. All mice were generated in a pure C57B6 background. Then, 8- to 14-week-old TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wildtype (wt) mice were used as bone marrow donors. Peripheral blood (50-80 μL per mouse) was obtained by jugular puncture and collected into EDTA-coated tubes for further analysis. Peripheral blood counts were measured with the Abacus Junior Vet System (Diatron) or processed for high-throughput (HT), quantitative FISH (QFISH).

Treatment and transplantation protocols were approved by the Ethical Committee of the “Carlos III” Health Institute, and mice were treated in accordance of the Spanish laws and the guidelines for “Humane Endpoints for Animals used in Biomedical Research.” All mice were maintained at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the recommendations of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Association.

Bone marrow transplantation and Cre induction

Bone marrow transplantation was performed as described27. Groups of 8 wild-type littermates (C57B6 background, 7-10 weeks old) per donor mouse were irradiated with 12 Gy the day before the transplantation. The following day, bone marrow of the donor mice was harvested from the femora and tibiae and 2-3 × 106 cells were injected per recipient. All experiments were performed on animals that underwent transplantation after a latency of at least 30 days.

TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre or TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice undergoing long-term polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pI-pC; Sigma-Aldrich) injections were used for serial transplantation. A total of 2 × 106 cells of donor bone marrow were transplanted into groups of 4 irradiated wild-type littermates as bone marrow recipients.

To induce the Cre expression, 15 μg/g body weight of pI-pC was injected intraperitoneally into animals that had undergone transplantation. Duration and frequency of pI-pC injections is indicated in the respective experiment.

G-CSF ELISA

Peripheral blood of euthanized mice was centrifuged and serum was frozen at −80°C until measurement. ELISA analysis of mouse G-CSF levels was carried out according to the manufacturer (Quantikine; R&D Systems).

FACS analysis and FACS sorting

For detailed bone marrow characterization, 10 × 106 bone marrow mononucleated cells (BMMCs) per animal were incubated with 3% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes. After washing cells once with PBS, anti–sca-1–PerCP-Cy5.5, lin cocktail-eFluor450, anti–FC-receptor–PE-Cy7, anti–CD34-eFluor660, anti–IL7-Alexa488 (all eBioscience), and anti–c-kit–APC-H7 (BD Pharmingen) antibodies were added and cells were incubated for 30 minutes. After washing cells once with PBS, 2μL of DAPI (200 μg/mL) was added

For BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) staining and cell-cycle analysis, 150 mg/kg BrdU was injected intraperitoneally 2 hours before the animals were killed. To summarize, 1 × 106 BMMCs were fixed for 20 minutes with the use of 70% ethanol and then denatured with 2N HCL solution. After neutralization using 0.1M sodium borate, cells were washed twice with PBS/1% BSA and incubated for 20 minutes with anti-BrdU–FITC antibody (BD Pharmingen). The samples were washed twice with PBS/1% BSA, and cells were resuspended in 10 μg/mL propidiume iodide (Sigma-Aldrich).

For apoptosis measurement, 2 × 106 BMMCs per animal were incubated with 3% BSA for 20 minutes. After washing cells once with cell culture media (DMEM; Gibco), samples were resuspended in 100 μL of annexin-V binding buffer (Apoptosis detection kit; BD Pharmingen) containing lin cocktail-eFluor450, anti–c-kit–APC-H7, and annexin-V–FITC (BD Pharmingen). Before analysis, 2 μL of Topro-3 (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen) was added to the samples.

For FACS sorting experiments, BMMCs were blocked with 3% BSA for 20 minutes and washed once with PBS. Cells were stained for 30 minutes with lin cocktail-eFluor450, anti–c-kit–APC-H7, and, where required, with anti–sca-1–PerCP-Cy5.5. After washing them once with PBS, we sorted samples by using a FACS Aria II sorter (BD Bioscience).

Colony-forming assay

For short-term colony-forming assay (CFA), 1 × 104, 2 × 104, or 4 × 104 of BMMCs were cultured in 35-mm dishes (StemCell Technologies) containing Methocult (StemCell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All experiments were performed as doublets and the number of colonies was counted on day +12 after manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis and experimental groups

Because the pI-pC–induced interferon release has various effects on the hematopoietic system, we used 4 experimental groups to exclude any effect of interferon in our mouse model. TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre with and without pI-pC injections and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt with and without pI-pC injections were compared with each other. All experiments were carried out with mice from at least 2 different donors, and a comparison of untreated versus pI-pC treated was performed in pairs by the use of mice from the same donor to minimize interindividual differences. In all analysis, a significance level of α = 0.05 was considered as statistically significant, and all graphs are displayed as mean value and SE. If not stated otherwise, “n” represents the number of analyzed mice in each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad prism software Version 5.0 (GraphPad).

Results

Acute TRF1 deletion progressively leads to pancytopenia and histopathologically proven BMF but not to telomere shortening

To study the effects of TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow, we crossed TRF1flox/flox mice with a conditional knock-out allele for TRF1, with Mx1-Cre mice, which express the Cre recombinase in the bone marrow as well as in several tissues like liver, heart, spleen, and kidney26. To avoid the potentially deleterious and complex effects of TRF1 deletion in other tissues, we used bone marrow transplantation, allowing us to selectively analyze the consequences of TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow. To this end, the bone marrow from TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice was transplanted into wild-type recipient littermates (see “Bone marrow transplantation and Cre induction”). PCR analysis for TRF1flox and TRF1 revealed complete engraftment of the transplanted transgenic bone marrow excluding any relevant participation of the original recipient marrow (Figure 1A). Thirty days after transplantation, we found a complete recovery of the peripheral blood counts and normal bone marrow histopathology in both groups (Figure 1B-C), indicating full reconstitution of the recipient bone marrow by the different genotypes.

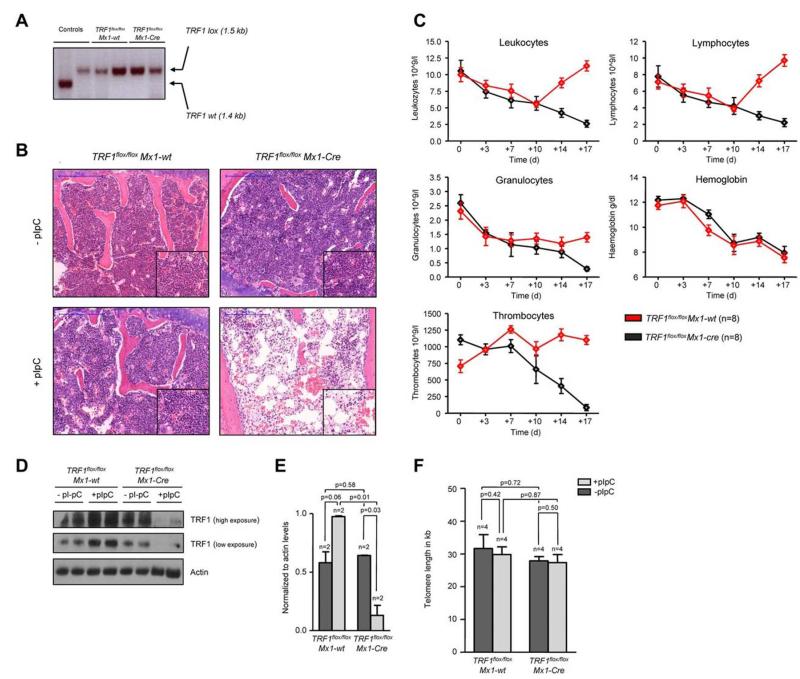

Figure 1. TRF1 deletion progressively leads to pancytopenia and histopathologically proven BMF but not to telomere shortening.

(A) PCR for wild-type and floxed TRF1 confirmed the absence of remaining recipient wild-type bone marrow in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt (lane 3 + 4) and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre (lane 5 + 6). Genomic control DNA of TRF1wt and TRF1flox/flox are shown (lane 1 + 2). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the sternal bone marrow of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animals without Cre induction and after +18 days. Image was captured with ×10 magnification (blue bar represents 200 μm), small image shows ×40 magnification. (C) Peripheral blood counts measured twice a week of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. No statistical difference was found at day 0 in all subpopulations between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (all P > .05) except for thrombocytes (P = .005). At day +18, all TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice showed statistically significant lower peripheral blood counts (all P < .005) except for hemoglobin levels (P = .55). Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (D) Western blot analysis of TRF1 protein levels of bone marrow protein extracts of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animals without pI-pC injections and after +18 days. Two different exposure times are shown. (E) Quantification of TRF1 protein levels in relation to actin protein levels (without pI-pC, dark gray bars and with pI-pC, light gray bars). Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (F) Telomere length analysis using Q-FISH of sternal bone marrow sections of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animals without (dark gray bars) and after 18 days of pI-pC treatment (light gray bars). Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison.

To delete TRF1 in the bone marrow, we induced Cre expression every second day by treating the mice with pI-pC (see Methods and supplemental Figure 1A). Eighteen days after induction of Cre (day +18), the mice were sacrificed because they presented with severe pancytopenia and poor health condition. At this end point, we found a significant reduction of TRF1 protein expression in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice, demonstrating a successful abrogation of TRF1 in the treated mice (Figure 1D-E). Reduced TRF1 protein levels also were confirmed by TRF1 immunofluorescence on day +18 at the single-cell level. Of note, although we found dramatically decreased TRF1 protein levels per cell, we did not find any single cell with completely absent TRF1 signals, most likely indicating that these cells are rapidly removed from the bone marrow (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

Histopathologic analysis of the bone marrow at day +18 showed a hypocelluar, aplastic bone marrow (Figure 1B) in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group consistent with BMF but no signs of hypocellularity/aplasia in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice. In line with the histologic findings, all mice in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group developed a progressive decrease of the peripheral blood counts resulting in pancytopenia. In contrast, the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt group (Figure 1C) showed stable or even increasing blood counts except for the hemoglobin levels owe to the blood withdrawal.

To investigate the impact of acute TRF1 abrogation on telomere length, telomere length in both groups was measured before and after TRF1 deletion. We observed no significant differences between both groups (Figure 1F). In summary, these findings indicate that TRF1 deletion progressively leads to BMF in the absence of detectable telomere shortening.

Progressive TRF1 deletion significantly reduces the number of HSC and progenitor cells and leads to increased compensatory proliferation

To understand the effect of progressive TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow, we injected pI-pC daily for a total of 7 days (supplemental Figure 1B). Using this approach, we obtained a significant decrease of TRF1 protein levels and a robust decrease of the bone marrow cellularity (supplemental Figure 3A-C), yet at the same time we could obtain sufficient bone marrow cells for further experimentation. First, we performed a detailed analysis of the different bone marrow subpopulations (Figure 2A-B). FACS analysis revealed an increase of HSCs in the pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt control group but a decrease in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group (Figure 2A-B). In the progenitor cell population, we found a significant decrease in the number of common lymphoid progenitors as well as the common myeloid progenitors in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre but not in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt group (Figure 2A-B). We also found a significant decrease in the more differentiated megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice compared with the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt controls (Figure 2A-B). In contrast, granulocyte-macrophage progenitors did not significantly differ between genotypes (Figure 2A-B).

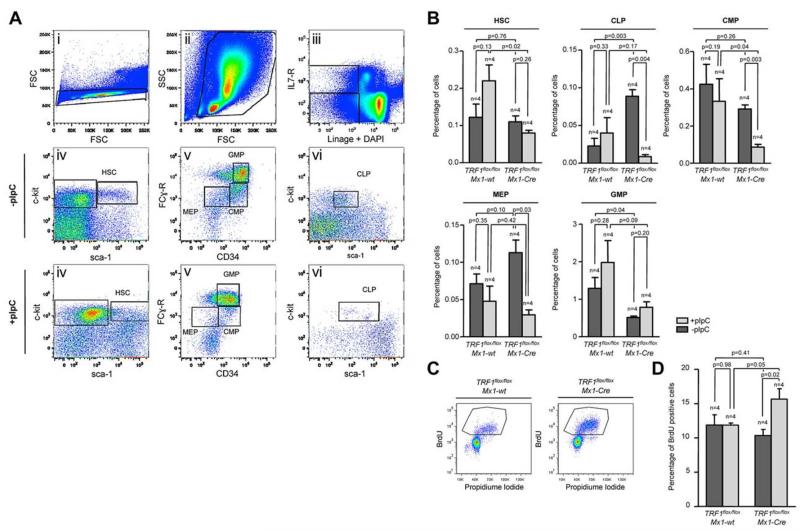

Figure 2. Induction of TRF1 deletion depletes HSC and progenitor cells and leads to increased compensatory proliferation.

(A) Representative FACS analysis of the HSC and progenitor cell populations. Single cells in panel Ai were further gated based on forward and side scatter (Aii). Including only viable cells without DAPI incorporation, BMMCs of (Aii) were separated on the basis of being lineage negative and IL-7 receptor positive or negative (Aiii). IL-7 receptor–positive cells were further analyzed based on the sca-1 and c-kit staining (Avi). Common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) were identified as sca-1 and c-kit low(+) cells. Lin and IL-7 receptor–negative cells were further distinguished on the basis of sca-1 and c-kit staining (Aiv). HSCs were identified as c-kit(+), sca-1(+). C-kit(+), sca-1(−) progenitor cells were further differentiated in (Av) on the basis of CD34 and Fc-receptor staining. CD34 and Fc-receptor low(+) cells were identified as megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitor cells (MEP), CD34(+), Fc-receptor low–positive cells as common myeloid progenitors (CMP), and CD34(+), Fc-receptor(+) cells were identified as granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP). (B) Quantification of the percentage of the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell subpopulations. The respective percentage was calculated in relation to the number of cells gated for forward and side scatter in panel Aii. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-C injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group, student paired t test for statistical comparison within the respective group (untreated vs treated). (C) Representative FACS analysis of BrdU incorporation after 2-hour pulse labeling in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice undergoing Cre induction. BMMCs were gated for singlet cells and forward and side scatter (FACS scatter gram not shown) and then further separated on the basis of BrdU and propidium iodide staining. (D) Quantification of BrdU-positive cells. The respective percentage was calculated in relation to the number of cells gated for forward and side scatter. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-C injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test and student paired t test was used for statistical comparison between respective TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups.

Because the induction of TRF1 deletion leads to a decrease of the HSC and progenitor cells, we asked whether the observed stem and progenitor cell depletion results in reduced proliferation rates in the bone marrow. To this end, we performed cell-cycle analysis and 2-hour BrdU pulse labeling to analyze for changes in the proliferation rate. Cell-cycle profile revealed significant increased S-phase and G2-M phase in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 3E-F). In line with the cell-cycle analysis, the number of BrdU-incorporating cells in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice was significantly increased compared with the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt controls (Figure 2 C-D). These findings indicate an increased compensatory proliferation of the remaining non-TRF1–deleted cells in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice despite significant reduction of stem and progenitor cells. Supporting the notion of increased compensatory proliferation in response to TRF1 ablation, we found significantly increased G-CSF levels in the blood of the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 3D), which is the main growth factor for granulocyte precursors. These results indicate that TRF1 deletion results in increased compensatory proliferation of the remaining non-TRF1–deleted bone marrow cells to compensate for loss of stem and progenitor cells.

Progressive TRF1 deletion leads to increased number of telomere-induced foci, increased p53-mediated induction of p21, and cellular senescence but no apoptosis

γH2AX can form foci that marks the presence of DSBs, and colocalization of γH2AX foci with telomeres indicates the presence of uncapped/dysfunctional telomeres, the so-called telomere damage associated foci or telomere-induced foci (TIFs)28. To address whether TRF1 ablation results in increased telomeric damage, we combined γH2AX immunofluorescence staining with telomere Q-FISH (immuno-Q-FISH) for colocalization analysis of γH2AX foci and telomeres in bone marrow sections (Figure 3A). We observed a significant increase in the number of TIFs in the pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre bone marrow but a decrease in similarly treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt control group (Figure 3B). Because dysfunctional telomeres as the result of TRF1 depletion can lead to chromosomal aberrations6,7, we next analyzed bone marrow metaphases. We did not observe significant differences in the number of chromosome aberrations between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

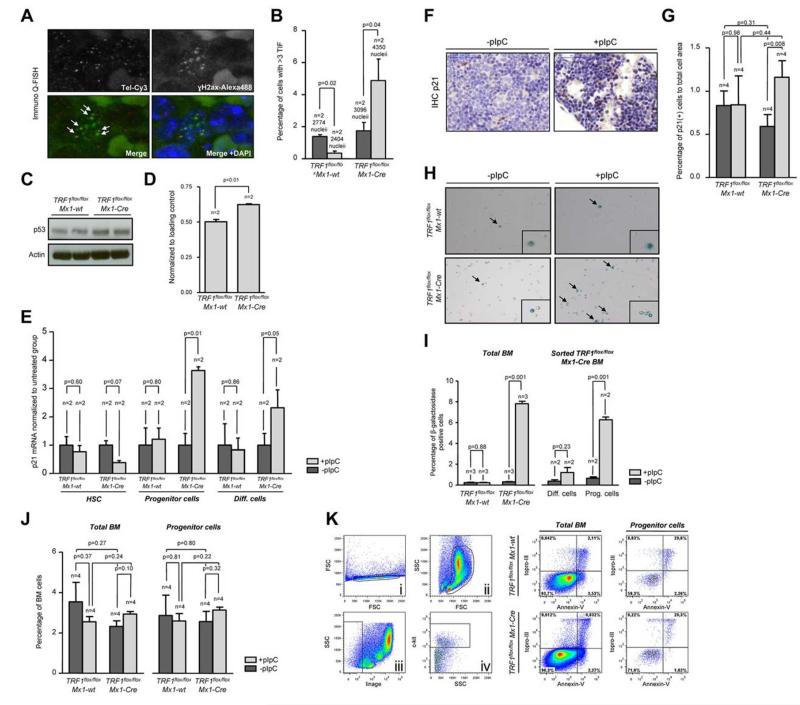

Figure 3. TRF1 deletion leads to increased number of TIFs and cellular senescence via p21 but no induction of apoptosis.

(A) Representative image of colocalization (indicated by white arrows) of γH2AX foci and telomeres using immuno Q-FISH. (B) Quantification of the number of TIFs per detected nucleus. Only cells showing 3 or more TIF were included. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-C injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (C) Western blot analysis of p53 protein levels of pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. (D) Quantification of Western blot analysis of the p53 protein levels in relation to respective actin levels. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (E) Fold change of quantitative PCR of p21 mRNA levels in FACS-sorted bone marrow cells sorted for HSC: lin (−), c-kit (+), sca-1 (+); progenitor cells: lin (−), ckit (+), sca-1 (#x2212;); and differentiated cells: lin (+). mRNA of p21 levels were normalized to actin levels, and statistical comparison was conducted with the Student t test between untreated and pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. (F) Representative image of p21 IHC staining of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice with and without pI-pC injections (×40 magnification, blue bar represents 50 μm). (G) Quantification of the p21 IHC-positive area (brown cells) in relation to the area of all cells. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-C injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test and Student paired t test was used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups. (H) Representative images of β-galactosidase staining in unsorted bone marrow. Images were captured with ×10 magnification, small window represents a magnified (20×) section of the image showing representative β-galactosidase–positive (indicated by black arrows) and –negative cells. (I) Quantification of the percentage of β-galactosidase positive cells per counted dish. Bar graph on the left represents unsorted bone marrow cells. On the right, quantification of FACS-sorted lin(+) differentiated cells and lin(−)c-kit(+) HSC and progenitors cells is shown. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-C injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (J) Quantification of the percentage of early apoptotic cells in all bone marrow cells and stem and progenitor cells. Quantification on the left represents all bone marrow cells, on the right, quantification of lin(−)c-kit(+) HSC and progenitors cells is shown. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars, mice undergoing pI-C injections by bright gray bars. Two-sided t test and Student t test was used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups. (K) Representative FACS analysis for apoptosis of pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. Single cells in Ki were further gated on the basis of forward and side scatter (Kii). Selected cells of Kii were analyzed as total bone marrow based on TO-PRO-3 and annexin-V staining or further separated in panel Kiii on the basis of negative linage staining. Lineage(−) cells were further distinguished in c-kit–positive and –negative cells (in Kiv). C-kit(+), lin(−) HSC, and progenitor cells (Kiv) were further analyzed on the basis of TO-PRO-3 and annexin-V staining. Annexin-V–positive and TOP-RO-3–negative cells were identified as early apoptotic cells.

Activation of a persistent DDR as the consequence of dysfunctional telomeres leads to up-regulation of p53 and to cellular senescence mediated by the p53 target gene p2129. To address whether conditional TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow induces p53-mediated senescence in vivo, we first analyzed p53 protein levels by Western blotting. We found significantly greater p53 levels in pI-pC–treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice compared with similarly treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt controls (Figure 3C-D). Next, we analyzed p21 mRNA levels by RT-PCR in FACS-sorted bone marrow cells. We found significantly greater p21 mRNA levels in progenitor cells from treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice, as well as in differentiated cells. Interesting, we observed the opposite tendency to have lower p21 mRNA levels in the HSC compartment on TRF1 deletion, which goes in line with compensatory hyperproliferation of this compartment. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) with anti-p21 antibodies directly on bone marrow sections confirmed a significant increase in p21 protein levels in the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group compared with the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt controls (Figure 3F-G). Again, we did not detect any relevant changes in p21 mRNA or protein levels in similarly treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt control mice (Figure 3E-G). In summary, elevated p53 and p21 levels are consistent with increased cellular senescence in vivo as the consequence of TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow.

To directly assess induction of senescence in vivo caused by TRF1 deletion, we used β-galactosidase staining directly on freshly isolated bone marrow cells (Figure 3H). The bone marrow from the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre–treated group showed a massive increase in the number of β-galactosidase–positive cells compared with the similarly TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt control group (Figure 3I). To identify the most affected cellular subpopulation, the bone marrow from treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice was sorted by FACS into differentiated and progenitor cells. Both subpopulations showed significantly increased numbers of β-galactosidase–positive cells, but progenitor cells accounted for the majority β-galactosidase–positive cells (Figure 3I). Interestingly, when we used the same approach for unsorted bone marrow cells with 3 additional days without Cre induction, no increased number of β-galactosidase positive cells was observed, indicating a rapid clearance of the senescent cells (supplemental Figure 4C).

Finally, we wanted to address whether, in addition to cellular senescence, apoptosis also contributed to depletion of HSC and progenitors on TRF1 deletion. Annexin-V analysis of early apoptotic cells (annexin-V positive, TO-PRO-3 negative) of all bone marrow cells and progenitor cells revealed no significant differences between the groups (Figure 3J-K). Our findings demonstrate that conditional TRF1 deletion induces p53-mediated p21 activation and subsequent induction of cellular senescence mainly in the progenitor cells because of persistent telomeric DNA damage in the absence of increased apoptosis.

Long-term induction of TRF1 deletion leads to massive impaired overall survival because of BMF after 8 weeks and massive telomere shortening

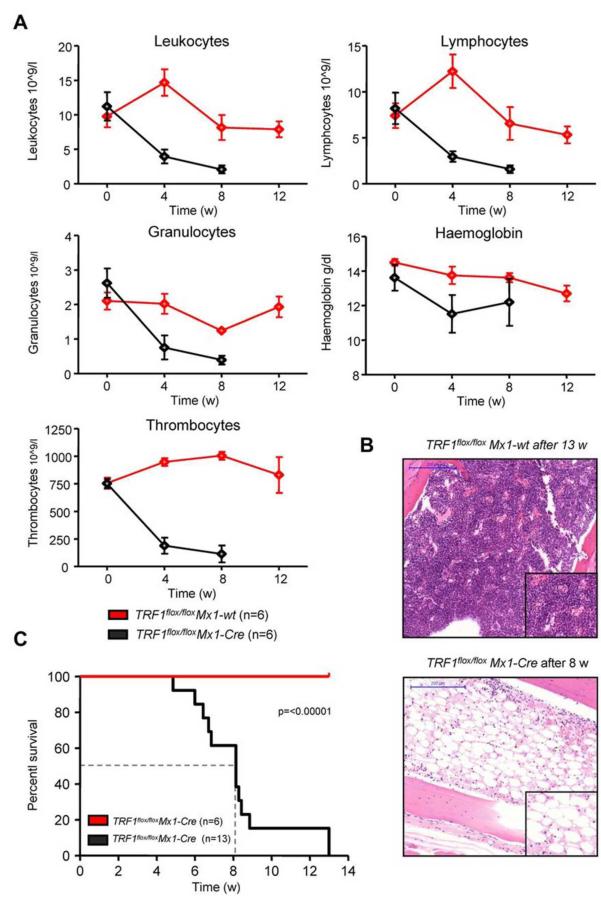

Next, we investigated the effects of long-term TRF1 dysfunction by inducing TRF1 deletion at a lower frequency, which could recapitulate a more similar situation to that of human patients with TIN2 mutations. To this end, we induced TRF1 deletion 3 times per week during several weeks (5-13 weeks) in a long-term approach (supplemental Figure 1C). Analysis of the peripheral blood counts revealed a progressive decrease in all 3 lineages over time in the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (Figure 4A). In agreement with development of pancytopenia, all treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice showed histopathologic signs of BMF characterized by a hypocellular or aplastic bone marrow (Figure 4B). In contrast, no signs of BMF were found in similarly treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt control animals. In addition, we observed a dramatically reduced median survival of 8.1 weeks for the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Long-term induction of TRF1 deletion results in BMF and reduced overall survival.

(A) Peripheral blood counts measured once a month of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice during Cre long-term induction via pI-pC. No statistical difference was found at day 0 in all the subpopulations between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (all P > .05). At 4 and 8 weeks after starting Cre induction, all TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice showed statistically significant lower peripheral blood counts (all P < .005) except for hemoglobin levels (P = .08 and P = .07 at week +4 and +8, respectively). Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (B) Exemplary hematoxylin and eosin staining of the sternal bone marrow of a TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animal 13 and 8 weeks, respectively, after the start of Cre induction. Image was captured with ×10 magnification (blue bar represents 200 μm), small image shows ×40 magnification. (C) Overall survival of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice undergoing long-term Cre induction. Dashed line represents median survival. Log-rank test was used for statistical comparison.

In this setting of a more chronic TRF1 dysfunction, we next analyzed telomere length in bone marrow sections by using quantitative telomere Q-FISH (Figure 5A). Strikingly, TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice undergoing long-term Cre-induction/TRF1 deletion showed a dramatic telomere shortening of approximately 15 kb within 7-9 weeks of treatment in comparison with TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice after 13 weeks of treatment (Figure 5B). Telomere length distribution revealed a massive increase in the abundance of shorter telomeres in the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group (Figure 5C). Analysis of the telomere length in relation to the respective untreated counterpart revealed that TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt animals showed 7.4% shorter telomeres after 13 weeks. Telomeres of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice after 7-9 weeks were found to be 44.7% shorter, resulting in an approximately 6-fold increased telomere shortening compared with the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt (Figure 5D). These results clearly show that chronic TRF1 dysfunction leads to a severe telomere shortening over time, similar to that observed in human patients with TIN2 mutations.

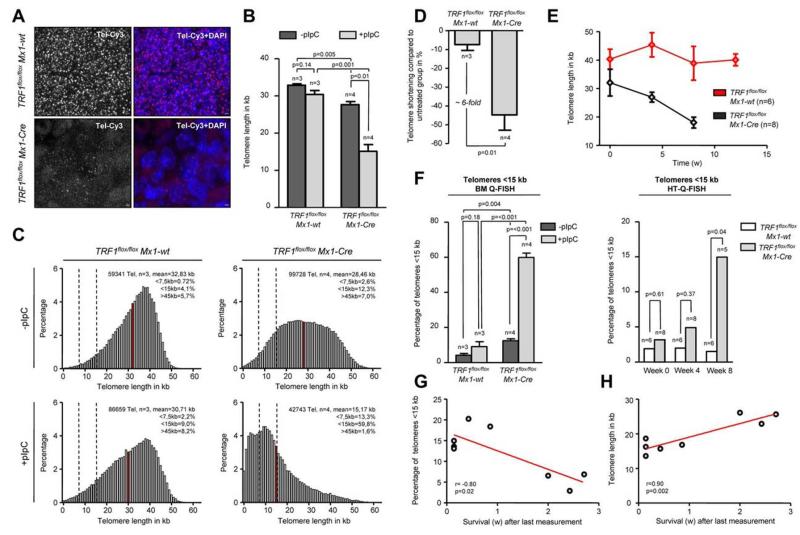

Figure 5. Long-term induction of TRF1 deletion leads to telomere shortening and significant increased number of short telomeres.

(A) Representative image of bone marrow Q-FISH of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice undergoing long-term Cre induction (×63 magnification and ×2 optical zoom). (B) Mean telomere length of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice with (after 7-9 and 13 weeks, respectively) and without long-term Cre induction. Mice without pI-pC–induced Cre expression are represented by dark gray bars and mice undergoing pI-pC injections by light gray bars. Two-sided t test and Student paired t test was used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups. (C) Telomere length distribution of all measured telomeres in the analyzed TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animals with and without Cre induction. Red line indicates the mean value calculated in panel B, and dashed lines represent 7.5 and 15 kb. All percentages given in the graph are calculated represent the mean values of the respective 3 or 4 measured mice. (D) Relative telomere length difference between the respective treated and untreated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (E) Telomere length over time of peripheral blood leukocytes in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre animals undergoing long-term pI-pC injections. TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice showed significant shorter telomeres after 4 and 8 of Cre induction (both P < .005), but no significant difference was observed before Cre induction (P = .26). Two-sided t test and used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups. (F) Quantification of the percentage of telomeres < 15 kb of analyzed mice of (B) using BM-Q-FISH and of (E) using HT-Q-FISH. Two-sided t test and used for statistical comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups of BM-Q-FISH, 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre subgroups of HT-Q-FISH. (G) Correlation between measured short telomeres (< 15 kb) of the last blood sample taken and remaining survival time in weeks of the mice. (H) Correlation between telomere length of the last blood sample taken and remaining survival time in weeks of the mice. Pearson correlation was used for statistical analysis.

Because Q-FISH analysis on bone marrow sections can only determine telomere length at the time of death, we set out to perform longitudinal telomere length studies on induction of TRF1 deletion. To analyze the telomere length dynamics over time, we used the Q-FISH method (HT-Q-FISH), which determines telomere length in a per-cell basis in peripheral blood30,31. HT-Q-FISH also allows for the determination of the abundance of short telomeres because it can quantify individual telomere signals per cell30,31. HT-Q-FISH analysis showed that telomere length progressively shortened over time in the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group (Figure 5E). In addition, HT-Q-FISH revealed a massive accumulation of short telomeres in the treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group (Figure 5F). Interestingly, both telomere length and the percentage of short telomeres per individual mice showed a significant correlation with the remaining overall survival of the individual treated TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (Figure 5G-H). These results demonstrate that chronic TRF1 deletion leads to a progressive decrease in telomere length, which eventually determines mouse longevity.

Mice undergoing long-term TRF1 deletion undergo replicative senescence and exhaustion because of telomere shortening

The aforementioned results suggest that the reduction of the HSC and progenitor cells and the consecutive compensatory increased proliferation of the remaining stem and progenitor cells maybe be responsible for the massive telomere shortening and accumulation of short telomeres induced on chronic TRF1 dysfunction, thus providing a molecular mechanism for the observations in human TIN2 patients. To confirm the supposed increased proliferation and replicative stress, we quantified the IHC for phospho-Histone3 and phospho-CHK1, known markers for cell proliferation and replicative stress, respectively32. TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice showed a significant relative increase in proliferation and replicative stress compared with TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice after 4 and 8 weeks of long-term Cre induction (supplemental Figure 5A-D).

In turn, accumulation of short telomeres can induce replicative senescence33,34. To analyze the consequences of the massive accumulation of short telomeres in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice, we performed β-galactosidase staining in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice after 4 weeks of long-term Cre induction/TRF1 deletion and 5 days without Cre induction. The TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group showed a significantly increased, approximately 13-fold greater number of β-galactosidase–positive cells (2.19%-0.16%, respectively) compared with the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt (Figure 6A-B). The number of β-galactosidase–positive cells in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt group was in the same range as previously found (Figure 3I). To test whether short telomeres affect proliferative capacities of the stem cells, we performed CFA after 4 weeks of long-term Cre induction. CFA showed significantly decreased capacity of forming colonies in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group (Figure 6C-D).

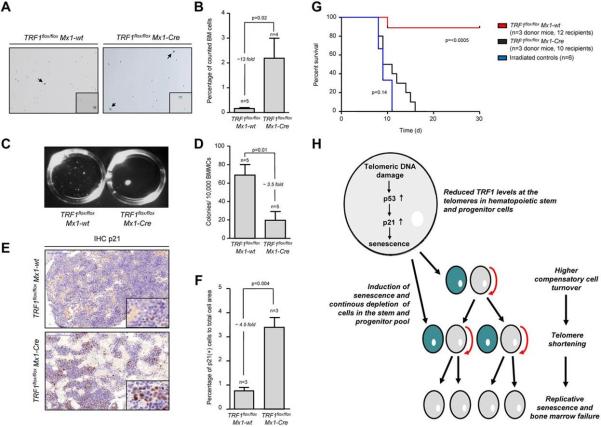

Figure 6. Mice undergoing long-term induction of TRF1 deletion undergo replicative senescence and exhaustion because of telomere shortening.

(A) β-galactosidase staining of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice after 4 weeks of long-term Cre induction and 5 days of pause before measurement to exclude any interferon related effects. Images were captured with ×10 magnification, small window represents a magnified (×20) section of the image showing representative β-galactosidase–positive (indicated by black arrows) and –negative cells. (B) Quantification of β-galactosidase staining of panel A. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (C) Macroscopic view of CFA assays of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice after 12 days. (D) Quantification of CFU assay of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice after 4 weeks of long-term Cre induction and 5 days of pause before culturing. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (E) Representative IHC staining for p21 of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice being bone marrow donor for serial transplantation. Mice underwent 8 weeks of long-term Cre induction and 5 days of pause before being euthanized for serial transplantation. Image was captured with ×20 magnification (blue bar represents 100 μm), small image shows ×80 magnification. (F) Quantification of the percentage of p21-positive area calculated to the area of all cells is shown on the right. Two-sided t test was used for statistical comparison. (G) Overall survival of mice undergoing serial transplantation. TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre bone marrow donor mice underwent 8 weeks of long-term Cre induction and had 5 days of pause before being killed as donors for serial transplantation. Both groups were compared with animals not receiving bone marrow transplantation. Log-rank test was used for comparison between TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice (P = < .0005) and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice were compared with mice without bone marrow transplantation (P = .14). (H) Proposed model of the consequences of reduced TRF1 levels in patients with TIN2 mutations.

To analyze the effects of long-term Cre induction after 8 weeks, we performed IHC of p21 in bone marrow sections. The number of p21-positive bone marrow cells was significantly increased in the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group, 4.5-fold greater compared with the p21 levels of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice. p21 levels of TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cwt mice were in the range as previously observed (Figure 6E-F). To analyze the functional consequences of short telomeres and increased p21 levels, we performed serial bone marrow transplantation after 8 weeks of long-term Cre induction in TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt and TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre mice. The bone marrow of the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-wt mice did not exhibit difficulties to repopulate a second time. In the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group, we found a tendency for prolonged survival compared with irradiated mice without bone marrow transplantation, but no transplanted bone marrow of the TRF1flox/flox Mx1-Cre group was able to stably repopulate over 4 weeks (Figure 6G). Our data indicate that accumulation of short telomeres because of chronic TRF1 deletion is the underlying mechanism of replicative senescence and impaired proliferative capacity in TRF1 deleted bone marrow.

Discussion

Here, we set out to test whether abrogation of TRF1 in the hematopoietic system recapitulates the clinical features of BMF associated with mutations in the telomere pathway (ie, patients with telomerase or shelterin mutations). We first show that acute TRF1 deletion results in BMF and progressive cytopenia in the absence of telomere shortening. Because of the severity of the phenotype mice had to be killed only 18 days after the induction of TRF1 ablation, which represents a lifespan of only 8 extra days compared with that of lethally irradiated mice. These findings indicate a severe dysfunction of the HSC/progenitor compartment as observed for chemotherapy and in line with previously studies confirm the essential nature of the TRF1 gene6,35. In the in vivo setting of the BM, TRF1 depletion leads to dysfunctional telomeres and to in vivo induction of cellular senescence via p53 mediated activation of p216.

Cellular senescence was specifically found in progenitor cells and, to a lesser extent, in differentiated cells, in agreement with the fact that these compartments have the highest cell cycle activity36. This progenitor cell depletion explains the phenotype observed in the closely clocked acute TRF1 deletion. As a result of the progenitor cell depletion, we found an increased compensatory proliferation of the no-TRF1–depleted stem cell pools (HSCs). This increased proliferation of HSC is mechanistically explained by lower p21 levels in the HSC compartment.37. Notably, we observed that TRF1-depleted cells did not contribute to cell division and were rapidly cleared of the bone marrow in the absence of increased apoptosis. In this regard, it is likely that phagocytosis of the TRF1 depleted senescent cells by macrophages in the bone marrow as observed for mature granulocytes may explain the clearance of senescent cells38.

Next, by deleting TRF1 at a lower frequency and during longer times, we aimed to induce a chronic TRF1 dysfunction, which could resemble more closely the human BMF syndromes associated with telomere dysfunction. In this setting, mice progressively developed cytopenia and BMF over time until reaching their end point. Mice undergoing acute TRF1 deletion did not show telomere shortening because of the acute depletion of the progenitor cell compartment and the short time span. In contrast, telomeres were found to undergo massive shortening with time in mice receiving less frequent long-term Cre induction. Furthermore, as a consequence of telomere shortening, we observed an accumulation of short telomeres and in vivo induction of replicative senescence in the bone marrow concomitant with impaired replicative capacity.

Importantly, our chronic TRF1 dysfunction mouse model recapitulates various clinical features of DKC patients carrying mutations in the shelterin TIN2 gene. Similar to the clinical course in DKC patients with TIN2 mutations, TRF1-deleted mice exhibit progressive pancytopenia over time, resulting in BMF10,39. Further, we found a reduced number of colony-forming units, indicating impaired bone marrow function as reported in patients with DKC40. In addition, the clinical feature of early onset of symptoms in patients with TIN2 mutations and the very short telomeres observed in these patients coincidences with the massive and rapid telomere shortening over a period of only few weeks, leading to impaired overall survival as observed in our mice14–16. In particular, mice with chronic TRF1 dysfunction showed approximately a 6-fold increase in telomere shortening over time compared with the control group, which is in a similar range to that observed in a prospective study demonstrating a 4-fold increase in telomere shortening in patients with DKC14. Furthermore, we found an excellent correlation between telomere length and percentage of short telomeres with the remaining lifespan of mice with TRF1 deletion in the bone marrow, highlighting the role of telomeres as a possible marker for clinical outcome in BMF syndromes. In this regard, in the clinical practice, short telomere length is used to identify DKC patients with TIN2 mutations16,18

Defects in telomere maintenance contribute to various types of BMF syndromes. Previous models for the pathogenesis of DKC proposed that stem cell dysfunction is caused by accelerated telomere shortening because of impaired functionality of the telomerase complex in the HSC because of mutations in the telomerase genes. As a consequence of telomerase deficiency, cycling HSC cannot properly maintain telomere length, resulting in progressive accumulation of short telomeres, a common clinical feature of DKC patients with impaired telomerase activity34,41,42. On the basis of our findings, we propose an additional mechanism leading to telomere shortening in the presence of a functional telomerase complex, such as it is the case of DKC patients with TIN2 mutations. Dysfunctional telomeres lead to activation of DDR and increased number of progenitor cells undergoing cellular senescence. To compensate for the constant progenitor cell lost, a greater cell turnover is needed to maintain blood homeostasis, resulting in telomere shortening and subsequent replicative senescence. We cannot completely rule out the possibility that TRF1-deleted cells can divide and contribute to the phenotype in our mice. However, on the basis of previous studies6,7, this possibility is unlikely without additional p53 inactivation.

In line with our findings, recent studies demonstrated that progenitor cells with high levels of DNA damage because of aging or irradiation are cleared from the bone marrow and only progenitor cells without increased DNA damage can contribute to hematopoiesis43,44. Further supporting our proposed mechanism, Wang et al demonstrated that mice deficient for the shelterin POT1b develop BMF at the age of 15 months45. Absence of POT1b resulted in dysfunctional telomeres, and DDR activation led to an intrinsic growth defect and progressive depletion of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Interestingly, POT1b-deficient mice with heterozygous telomerase deficiency (mTERC+/−) develop even earlier DKC features as BMF and cutaneous phenotypes, highlighting the role of telomere maintenance for the stem cell pool46,47.

Interestingly, all known TIN2 mutations in DKC patients are observed in the exon 6 close-by or in the region encoding for the TRF1 binding site, raising the possibility that impaired TIN2-TRF1 interaction accounts for the pathogenesis of DKC. In vitro studies revealed that deletion of the TRF1 binding site of TIN2 leads to reduced TRF1 levels in the shelterin complex20–23. Further supporting this notion, the recent study of Sasa et al reports the case of a 4-year-old patient with a TIN2 mutation in the TRF1 binding site and very short telomeres19. Coimmunoprecipitation assay resulted in a severely impaired ability of the patient’s TIN2 mutation to interact with TRF1. In addition, Kim et al reported that human fibroblasts with a truncated TIN2 protein lacking the TRF1 binding site showed significantly reduced TRF1 levels20. In striking similarity to our data, these fibroblasts showed impaired cell growth, an increased number of DNA damage foci on the telomeres indicative for dysfunctional telomeres, and an increased number of β-galactosidase senescent cells. However, despite similarities of our mouse model with the observations in patients with TIN2 mutations, further data are needed to circumstantiate the hypothesis of impaired TIN2-TRF1 interaction responsible for the pathogenesis of DKC. In summary, we provide the first mouse model simulating DKC features caused by alteration of TRF1 and the conditional TRF1 deletion represents a useful model to further investigate the pathogenesis of DKC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rosa Serrano and Ester Collado for the excellent mouse care. F.B. is funded by the “Mildred-Scheel-Stipendium” of the “Deutsche Krebshilfe.” M.F. is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education through FPU fellowship. P.M. is funded by a “Ramón y Cajal” grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science. Research in the Blasco laboratory is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Projects SAF2008-05384 and CSD2007-00017, the Madrid Regional Government Project S2010/BMD-2303 (ReCaRe), the European Union FP7 Project FHEALTH-2010-259749 (EuroBATS), The European Research Council (ERC) Project GA#232854 (TEL STEM CELL), the Körber European Science Award from the Körber Foundation, the Preclinical Research Award from Fundación Lilly (Spain), Fundación Botín (Spain), and AXA Research Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Blackburn EH. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell. 2001;106(6):661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19(18):2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez P, Blasco MA. Telomeric and extra-telomeric roles for telomerase and the telomere-binding proteins. Nat Rev Cancer. 11(3):161–176. doi: 10.1038/nrc3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shore D, Bianchi A. Telomere length regulation: coupling DNA end processing to feedback regulation of telomerase. EMBO J. 2009;28(16):2309–2322. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez P, Blasco MA. Role of shelterin in cancer and aging. Aging Cell. 9(5):653–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez P, Thanasoula M, Munoz P, et al. Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev. 2009;23(17):2060–2075. doi: 10.1101/gad.543509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sfeir A, Kosiyatrakul ST, Hockemeyer D, et al. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell. 2009;138(1):90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008;111(9):4446–4455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2353–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011:480–486. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(10):640–649. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dokal I, Vulliamy T. Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematologica. 2010;95(8):1236–1240. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage SA, Alter BP. The role of telomere biology in bone marrow failure and other disorders. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129(1-2):35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alter BP, Rosenberg PS, Giri N, Baerlocher GM, Lansdorp PM, Savage SA. Telomere length is associated with disease severity and declines with age in dyskeratosis congenita. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):353–359. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.055269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vulliamy TJ, Kirwan MJ, Beswick R, et al. Differences in disease severity but similar telomere lengths in genetic subgroups of patients with telomerase and shelterin mutations. PLoS One. 6(9):e24383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, et al. Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2007;110(5):1439–1447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vulliamy TJ, Marrone A, Knight SW, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation. Blood. 2006;107(7):2680–2685. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Hossain U, Walne A, Dokal I. Telomere length measurement can distinguish pathogenic from non-pathogenic variants in the shelterin component, TIN2. Clin Genet. 2012;81(1):76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasa G, Ribes-Zamora A, Nelson N, Bertuch A. Three novel truncating TINF2 mutations causing severe dyskeratosis congenita in early childhood. Clin Genet. 2012;81(5):470–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SH, Davalos AR, Heo SJ, et al. Telomere dysfunction and cell survival: roles for distinct TIN2-containing complexes. J Cell Biol. 2008;181(3):447–460. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH, Kaminker P, Campisi J. TIN2, a new regulator of telomere length in human cells. Nat Genet. 1999;23(4):405–412. doi: 10.1038/70508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takai KK, Kibe T, Donigian JR, Frescas D, de Lange T. Telomere protection by TPP1/POT1 requires tethering to TIN2. Mol Cell. 2011;44(4):647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye JZ, de Lange T. TIN2 is a tankyrase 1 PARP modulator in the TRF1 telomere length control complex. Nat Genet. 2004;36(6):618–623. doi: 10.1038/ng1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savage SA, Calado RT, Xin ZT, Ly H, Young NS, Chanock SJ. Genetic variation in telomeric repeat binding factors 1 and 2 in aplastic anemia. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(5):664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savage SA, Giri N, Jessop L, et al. Sequence analysis of the shelterin telomere protection complex genes in dyskeratosis congenita. J Med Genet. 2011;48(4):285–288. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.082727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kühn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269(5229):1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samper E, Fernandez P, Eguia R, et al. Long-term repopulating ability of telomerase-deficient murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2002;99(8):2767–2775. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takai H, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr Biol. 2003;13(17):1549–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Y, Chan SS, Chang S. Telomere dysfunction and tumour suppression: the senescence connection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(6):450–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canela A, Vera E, Klatt P, Blasco MA. High-throughput telomere length quantification by FISH and its application to human population studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(13):5300–5305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609367104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernardes de Jesus B, Schneeberger K, Vera E, Tejera A, Harley CB, Blasco MA. The telomerase activator TA-65 elongates short telomeres and increases health span of adult/old mice without increasing cancer incidence. Aging Cell. 2011;10(4):604–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toledo LI, Murga M, Fernandez-Capetillo O. Targeting ATR and Chk1 kinases for cancer treatment: a new model for new (and old) drugs. Mol Oncol. 5(4):368–373. 3022. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(8):611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brümmendorf TH, Balabanov S. Telomere length dynamics in normal hematopoiesis and in disease states characterized by increased stem cell turnover. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1706–1716. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlseder J, Kachatrian L, Takai H, et al. Targeted deletion reveals an essential function for the telomere length regulator Trf1. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(18):6533–6541. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6533-6541.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelhardt M, Kumar R, Albanell J, Pettengell R, Han W, Moore MA. Telomerase regulation, cell cycle, and telomere stability in primitive hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1997;90(1):182–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287(5459):1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rankin SM. The bone marrow: a site of neutrophil clearance. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(2):241–251. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steele JM, Sung L, Klaassen R, et al. Disease progression in recently diagnosed patients with inherited marrow failure syndromes: a Canadian Inherited Marrow Failure Registry (CIMFR) report. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(7):918–925. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita in all its forms. Br J Haematol. 2000;110(4):768–779. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirwan M, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita, stem cells and telomeres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792(4):371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mason PJ, Wilson DB, Bessler M. Dyskeratosis congenital—a disease of dysfunctional telomere maintenance. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5(2):159–170. doi: 10.2174/1566524053586581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohrin M, Bourke E, Alexander D, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error-prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(2):174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Seita J, Nussenzweig A, Hoeijmakers J, Weissman IL. Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature. 2007;447(7145):725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature05862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Shen MF, Chang S. Essential roles for Pot1b in HSC self-renewal and survival. Blood. 2011;118(23):6068–6077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He H, Wang Y, Guo X, et al. Pot1b deletion and telomerase haploinsufficiency in mice initiate an ATR-dependent DNA damage response and elicit phenotypes resembling dyskeratosis congenita. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(1):229–240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01400-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hockemeyer D, Palm W, Wang RC, Couto SS, de Lange T. Engineered telomere degradation models dyskeratosis congenita. Genes Dev. 2008;22(13):1773–1785. doi: 10.1101/gad.1679208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.