Abstract

Background

Stroke is associated with an increased risk of dementia. However, it is unclear if risk of stroke in those free of stroke, particularly in non-elderly populations, leads to differential rates of cognitive decline. Our aim was to assess whether risk of stroke in midlife was associated with cognitive decline over 10 years of follow-up.

Methods

We studied 4,153 men and 1,657 women, mean age 55.6 years at baseline, from the Whitehall II study, a longitudinal British cohort study. We used the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) that incorporates age, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, smoking, prior cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy, and use of antihypertensive medication. Cognitive tests included reasoning, memory, verbal fluency, and vocabulary assessed three times over ten years. Longitudinal associations between FSRP and its components were tested using mixed effects models and rates of cognitive change over 10 years were estimated.

Results

Higher stroke risk was associated with faster decline in verbal fluency, vocabulary and global cognition. For example, for global cognition there was greater decline in the highest FSRP quartile (−0.25 of a standard deviation; 95% CI: −0.28 to −0.21) compared to the lowest risk quartile (P=0.03). No association was observed for memory and reasoning. Of the individual components of FSRP only diabetes was independently associated with faster cognitive decline (β=−0.06; 95% CI:−0.01, −0.003, P=0.03).

Conclusion

Elevated stroke risk is associated with accelerated cognitive decline over 10 years. Aggregation of risk factors may be especially important in this association.

Keywords: vascular risk factors, cognitive decline, Framingham Stroke Risk Profile, aging, midlife

1. Introduction

Stroke increases the risk of dementia considerably [1–4]. In community-based studies, the prevalence of post stroke dementia in stroke survivors is about 30% and the incidence of new onset dementia after stroke increases from 7% after 1 year to 48% after 25 years [5]. Cognitive impairment is three times more common in people who have had a stroke than those who have not [6]. Even in the absence of stroke, individuals with a high risk of stroke have substantially higher cognitive deficits [7]. Individual risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking that predispose to stroke have been linked to adverse structural brain changes, cognitive impairment and dementia [8–17]. Moreover, there is evidence that vascular risk factors predispose one to both vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [5,18]. The clustering of risk factors may be particularly important and may increase the risk of cognitive impairment in an additive or synergistic manner, setting individuals on a trajectory of cognitive decline in advance of clinically detectable symptoms of cognitive impairment and dementia [16]. Current practice guidelines on management and treatment of cardiovascular disease, both coronary heart disease and stroke, recommend use of multifactorial risk prediction models. These risk scores offer an effective evaluation of vascular risk particularly in younger populations where the prevalence of stroke is low but risk of stroke may nevertheless be present due to accumulation of low to moderate risk on multiple risk factors for stroke. Identification of associations of sub-clinical vascular risk with cognitive decline at the ‘brain at risk’ stage is important and provides a great opportunity for prevention [19,20].

The Framingham risk scores are among the most widely validated and commonly used risk algorithms in clinical and research settings. However, their utility for predicting cognitive deficits in relation to vascular risk has remained relatively unexplored. The Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) uses routinely measured risk factors to estimate 10-year risk of stroke. A number of studies have examined the relation of the FSRP in predicting cognitive deficits. The FSRP has been shown to be associated with incident cognitive impairment [21] and worse performance on various cognitive tests such as delayed verbal memory, verbal fluency [22] and abstract reasoning [7]. However, the few studies that have examined FSRP in relation to cognition are either limited by their cross-sectional design [7,22,23], were conducted in a small selected population [24] or had a short follow-up and used a single item measure of cognitive status [21].

We sought to examine the association between stroke risk and longitudinal change in cognitive test scores, using three repeated cognitive measures over a ten-year period in a large sample of middle aged individuals.

2. Methods

2.1 Study population

The Whitehall II study was established in 1985 on 10,308 civil servants (6,895 men and 3,413 women). Details of the cohort and its follow- up have been described previously [25]. Briefly, all London-based civil servants aged 35–55 years in 20 departments in London, United Kingdom, were invited to participate. In total, 73 % of those invited agreed to participate in phase 1 (1985–1988) which consisted of a clinical examination and a self- administered questionnaire. Clinical examination included measures of blood pressure, anthropometry, biochemistry, neuroendocrine function and subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease. Subsequent phases of data collection have alternated between a questionnaire alone phase and a questionnaire accompanied by clinical examination. Cognitive testing was introduced to the full cohort at Phase 5 (1997–1999) and repeated at Phase 7 (2002–2004) and Phase 9 (2007–2009). All participants provided informed consent; the University College London ethics committee approved the study.

2.2 Assessment of Framingham Stroke Risk Profile

The FSRP is a clinical risk score that is used to calculate a gender specific 10-year probability of stroke for individuals who are free of stroke at baseline. The original algorithm is based on prediction of 427 stroke events observed over a 10-year follow up period for 2,372 men and 3,362 women in the Framingham Heart Study. The FSRP is based on the following risk factors: age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), antihypertensive medication, diabetes, cigarette smoking status, history of cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) as determined by ECG [26,27]. The FSRP has been shown to strongly predict incidence of stroke in our cohort [28].

We drew risk score components from questionnaire and clinical examination data at Phase 5 (1997-199) in those free of stroke. Blood pressure was taken twice in the sitting position after 5 minutes rest with a Hawksley random-zero sphygmomanometer. The average of the two readings was used in the analysis. Antihypertensive medication included diuretics, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors and calcium channel blockers. Diabetes was defined by a fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or a 2-hour post load glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L or reported doctor diagnosed diabetes, or use of diabetes medication [29]. Participants were categorized with respect to cigarette smoking status as current smokers or past/non smokers. History of cardiovascular disease was based on clinical examination at phases 1, 3, or 5 (e.g. electrocardiograms and angiograms) and corroborated records obtained from general practitioners or hospitals. The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and left ventricular hypertrophy was made using a standard 12-lead ECG and the Minnesota Code Classification system for Electrocardiographic findings (atrial fibrillation: code 3-1 for High Amplitude R-waves; LVH: code 8-3-1 for Arrhythmias). The stroke risk profile expressed as a predicted 10-year probability of incident stroke (%), was computed using beta coefficients based on the Cox proportional hazards regression model in the Framingham study [26,27].

2.3 Assessment of cognitive function

The cognitive test battery consists of five standard tasks to assess performance in various cognitive domains. In our cohort these tests have been shown to be sensitive to detecting small changes in cognitive function over time in participants as young as 45–49 years of age [30].

The Alice Heim 4-I (AH4-I) is composed of a series of 65 verbal and mathematical reasoning items of increasing difficulty [31]. It tests inductive reasoning, measuring the ability to identify patterns and infer principles and rules. The time allowed for this test was 10 minutes. Short-term verbal memory was assessed with a 20-word free recall test. Participants were presented a list of 20 one or two syllable words at two second intervals and were then asked to recall in writing as many of the words in any order and had two minutes to do so.

We used two measures of verbal fluency: phonemic and semantic. Phonemic fluency was assessed via “S” words and semantic fluency via “animal” words [32]. Participants were asked to recall in writing as many words beginning with “S” and as many animal names as they could. One minute was allowed for each test. Vocabulary was assessed using the Mill Hill Vocabulary test, used in its multiple-choice format, consisting of a list of 33 stimulus words ordered by increasing difficulty and six response choices [33]. In addition, a global cognitive score was created using all five tests described above by first standardizing raw scores on each test to z-scores (mean=0; standard deviation (SD)=1) using the baseline mean and standard deviation value in the entire cohort for each test. Z-scores were then averaged to yield the global cognitive score.

2.4 Covariates

Our analyses were adjusted for important demographic and health related factors including age, sex, ethnicity, education, depressive symptoms, physical activity and alcohol use. Although age and sex are both components of the FSRP, we included them as covariates because of their established association with cognitive function. Age was centered at the mean value for the analytic sample. Ethnicity was categorized into (1) white and (2) other ethnic groups. Education was measured as highest level of education achieved. Categories included (1) elementary or lower secondary, (2) higher secondary (A′ levels), and (3) first university degree or higher. We also assessed the effect of occupational position, classified as administrative, professional or executive, and clerical or supportive position. We also adjusted the analyses for depressive symptoms and health behaviors that in our cohort were shown to be associated with cognitive outcomes [34,35]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the four-item depression subscale of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and had two categories (0–3 and 4 or more). Alcohol consumption was assessed using questions on the number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the last 7 days. This information was divided into “measures” of spirits, “glasses” of wine, and “pints” of beer and converted to number of units of alcohol with each unit corresponding to 8 g of ethanol. For example a standard measure of spirits and a glass of wine are considered to contain 8 g of alcohol and a pint of beer 16 g of alcohol. Participants’ alcohol consumption was categorized as follows: none (0 units/week), moderate (1–14 for women and 1–21 for men), and heavy (>14 for women and >21 for men). Physical activity level was determined from phase 5 questionnaires that included 20-items on frequency and duration of participation in different leisure time physical activities (e.g. walking, general housework, cycling, sports) that were used to compute hours per week of each intensity level. Physical activity level was categorized as follows: high (>2.5 hours/week of moderate or >1 hour/week of vigorous physical activity), moderate (between 1 and 2.5 hours/week of moderate physical activity), and low (<1 hour/week of moderate and <1 hour week of vigorous physical activity)

2.5 Statistical analysis

For ease of interpretation, we categorized stroke risk into quartiles with the first quartile representing lowest risk and the fourth quartile representing highest stroke risk. To allow comparability of the five cognitive tests these were standardised to z scores, as described previously.

We used linear mixed effects models to estimate 10-year decline and associated 95% confidence intervals in each of the five measures of cognitive function. This method uses all available data over the 10 year follow-up period including those with one or two missing cognitive tests and takes into account the intra-individual correlation inherent in repeated measures. In our models, fixed effects included terms for time, the main effect term for each variable (stroke risk, age, sex, ethnicity, education, depressive symptoms, physical activity, and alcohol use), and interactions between time and each variable. The interaction between a given variable and time represents the effect of that variable on change in cognitive score over time. In addition to these main effects, two random effects were included; one for the intercept and one for the slope.

The stroke risk*time*sex interaction did not suggest sex differences in the rate of cognitive decline, thus our analyses were not stratified by sex. Our final models adjusted for demographic factors included terms for FSRP quartile, time, age, sex, ethnicity and education, and the interaction between time and each of FSRP quartile, age, sex, ethnicity and education. An interaction term for FSRP quartile and age was also included. Additional models included terms for the demographics adjusted models plus physical activity, alcohol use and depressive symptoms, and their interaction with time. The low stroke risk quartile was used as the referent category to obtain p-values for the difference in cognitive change in the remaining 3 quartiles. The p-value for trend was based on modelling stroke risk as a continuous variable with individuals in each risk quartile assigned the median value of the group. We conducted supplementary analyses to further explore each FSRP component as an independent risk factor for cognitive decline.

We also undertook sensitivity analyses to test robustness of our main findings. We modelled the association between FSRP and cognitive decline taking FSRP as continuous variable in order to represent a broader range of stroke risk. We carried out the same analyses as outlined above on log-transformed FSRP scores. We also conducted additional analyses accounting for interim events (i.e. incident stroke), and missing cognitive function data in our analyses and tested for interaction with APOE ε4 carrier status (defined as presence or absence of ≥ 1 APOE ε4 allele) in a subset of the study population with these data (N=4,936).

Analyses were performed using Proc Mixed procedure in SAS software (version 9; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

Of 10,308 participants at inception of the Whitehall II study (1985–1988), 7,830 (75.9%) participated in Phase 5 (1997–1999), the baseline of the current analysis. We included participants for whom Framingham stroke risk could be calculated at Phase 5, and who had at least one cognitive test measure over the follow-up (n=6,118). Our analysis is based on 5,810 individuals (4,153 men and 1,657 women), after excluding participants with prevalent stroke (n=48) or those missing data for covariates (n=260); 73% of participants had complete data at all 3 phases and 20.2% at 2 phases. Restricting the analyses to participants with complete data at all 3 phases did not significantly change our results. Compared to individuals not included in this analyses our sample included individuals who were younger (55.6 years vs 57.5 years at phase 5, P <0.001) and more educated (28.0% vs 15% with a university degree, P <0.001). Among participants who had at least one cognitive data over 3 waves, those with data at all 3 waves were different to those with data at one or two waves; they had a lower FSRP (4.3% vs 5.1%, P<0.001), were younger (55.2 years vs 56.7 years, P<0.001) and mostly men (72% vs 67%, P <0.001). There was also a higher proportion of individuals with university education (29.8% vs 24.9%, P<0.01). Mean FSRP in our analytical sample was 4.5 (SD=3.5, range=1% −78%). Detailed characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1 (See Supplementary Table 1 for quartile specific characteristics).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample (Phase 5, 1997–1999)

| Mean Framingham Stroke Risk | 4.5 (3.5) |

| FSRP components | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 55.6 (6.0) |

| Men, n (%) | 4153 (71.5) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 123.0 (16.4) |

| Antihypertensive medications, n (%) | 733 (12.6) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 225 (3.9) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 563 (9.7) |

| History of CVD, n (%) | 331 (5.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 29 (0.5) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, n (%) | 290 (5.0) |

| Covariates | |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Lower primary/secondary | 2554 (43.9) |

| A levels | 1522 (26.2) |

| University | 1734 (29.8) |

| White ethnicity, n (%) | 5370 (92.4) |

| Depressive symptoms, n (%) | 716 (12.3) |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | |

| None | 871 (14.9) |

| Moderate | 3522 (60.6) |

| Heavy | 1417 (24.4) |

| Physical activity, n (%) | |

| Low | 1737 (29.9) |

| Moderate | 975 (16.8) |

| High | 3098 (53.3) |

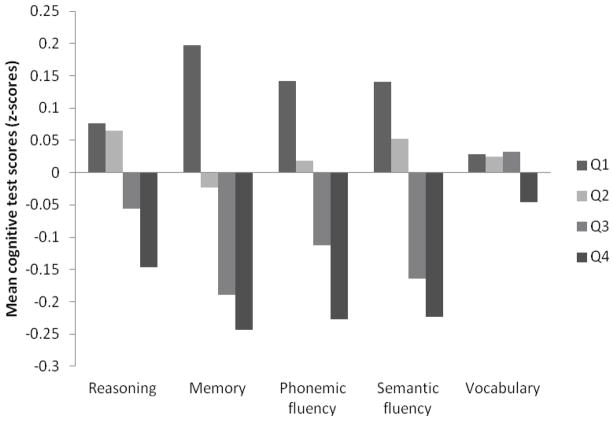

Mean cognitive test scores (z-scores) at baseline (Phase 5) by FSRP quartile are presented in the Figure. Persons in the highest stroke risk quartile had lower mean cognitive test scores compared to those in the lowest risk quartile and there was a negative trend in cognitive test scores across the three stroke risk groups (P for trend =0.001 on all tests except vocabulary; P=0.07).

Figure.

Mean Cognitive test scores at Phase 5 by Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) quartile

Estimates of 10-year change in cognitive z-scores as a function of stroke risk at baseline are presented in Table 2. In models adjusted for demographic factors, increased stroke risk was associated with faster cognitive decline for verbal fluency, vocabulary and global cognition. For example, compared with a decline of −0.32 SD unit per 10 years in phonemic fluency test, for persons in the lowest stroke risk quartile, cognitive decline was −0.39 SD (95% CI:−0.46 to −0.32) and −0.41 SD (95% CI:−0.48 to −0.34) over 10 years for those in the third and fourth quartile respectively. Similarly, in models adjusted for demographic and health related factors, those in the fourth FSRP quartile showed faster decline in verbal fluency, vocabulary and global cognition. Compared to the lowest stroke risk quartile, there was 0.04 SD units faster decline in global cognition in the fourth stroke risk quartile compared to the lowest risk quartile (P=0.03). These differences were only evident when comparing quartile 4 (FSRP ≥ 6%) to the lowest risk referent quartile. Adjusting associations for occupation, an indicator of socioeconomic status (instead of education) did not considerably change the results.

Table 2.

Cognitive change as a function of stroke risk (FSRP); estimates derived from linear mixed models using 3 assessments over 10 years

| Cognitive tests | FSRP quartile

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (mean=2.4%)

|

2 (mean=4.0%)

|

3 (mean=5.0%)

|

4 (mean=9.3%)

|

|

| 10-year cognitive change (95% CI) | ||||

| Adjusted for demographics | ||||

| Reasoning | −0.31 (−0.34, −0.28) | −0.30 (−0.34, −0.26) | −0.33 (−0.38, −0.29) | −0.33 (−0.37, −0.29) |

| Memory | −0.23 (−0.29, −0.17) | −0.18 (−0.26, −0.10) | −0.23 (−0.32, −0.14) | −0.20 (−0.24, −0.08) |

| Phonemic fluency | −0.32 (−0.37, −0.27) | −0.34 (−0.40, −0.28) | −0.39 (−0.46, −0.32) | −0.41 (−0.48, −0.34) * |

| Semantic fluency | −0.22 (−0.27, −0.17) | −0.26 (−0.33, −0.22) | −0.26 (−0.33, −0.19) | −0.30 (−0.36, −0.24) * |

| Vocabulary | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.09) | 0.03 (−0.004, 0.08) | −0.008 (−0.04, 0.03) † |

| Global cognition | −0.21 (−0.23, −0.18) | −0.21 (−0.23, −0.18) | −0.23 (−0.26, −0.21) | −0.24 (−0.27, −0.21) * |

| Adjusted for demographics and health related factors | ||||

| Reasoning | −0.33 (−0.36, −0.29) | −0.32 (−0.36, −0.28) | −0.35 (−0.40, −0.30) | −0.35 (−0.40, −0.30) |

| Memory | −0.25 (−0.32, −0.18) | −0.20 (−0.28, −0.12) | −0.25 (−0.34, −0.16) | −0.18 (−0.27, −0.009) |

| Phonemic fluency | −0.33 (−0.39, −0.27) | −0.34 (−0.41, −0.28) | −0.39 (−0.47, −0.32) | −0.42 (−0.48, −0.13) * |

| Semantic fluency | −0.21 (−0.27, −0.16) | −0.27 (−0.33, −0.20) | −0.25 (−0.32, −0.18) | −0.29 (−0.36, −0.22) * |

| Vocabulary | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.08) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) † |

| Global Cognition | −0.21 (−0.24, −0.19) | −0.16 (−0.24, −0.18) | −0.24 (−0.27, −0.20) | −0.25 (−0.28, −0.21) * |

Difference in mean cognitive change compared to referent quartile 1,

p <0.05,

p <0.01

NOTE. Models adjusted for demographics include age centered at the mean, sex, ethnicity and education. Health related factors include depressive symptoms, physical activity and alcohol consumption

We further investigated individual FSRP components as independent risk factors for cognitive decline over 10 years, relating each of the FSRP components to global cognitive function. In models adjusted for demographics and health related factors, only diabetes (β=−0.06; 95% CI: −0.01 to −0.003, P=0.03) was independently and inversely associated with decline in global cognition over 10 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of vascular risk factor components of FSRP and cognitive decline; estimates derived from linear mixed models using 3 assessments over 10 years

| Risk factor | Change in global cognition

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for demographics

|

Adjusted for demographic and health related factors

|

|||||

| β | 95 % CI | p | β | 95 % CI | p | |

| SBP | −0.01 | (−0.04, 0.02) | 0.39 | −0.01 | (−0.04, 0.02) | 0.41 |

| Diabetes | −0.04 | (−0.01, 0.003) | 0.05 | −0.06 | (−0.01, −0.003) | 0.03 |

| Smoking | −0.03 | (−0.07, 0.003) | 0.07 | −0.03 | (−0.07, 0.003) | 0.08 |

| History of CVD | 0.002 | (−0.04, 0.05) | 0.93 | 0.001 | (−0.04, 0.05) | 0.94 |

| AF | −0.05 | (−0.22, 0.12) | 0.53 | −0.07 | (−0.20, 0.11) | 0.54 |

| LVH | −0.04 | (−0.08, 0.003) | 0.08 | −0.04 | (−0.08, −0.0004) | 0.05 |

NOTE. Models adjusted for demographics include age centered at the mean, sex, ethnicity and education. Health related factors include depressive symptoms, physical activity and alcohol consumption

Finally, we obtained similar results in analyses of stroke risk as a continuous variable. Here too verbal fluency, vocabulary and global cognition were associated with cognitive decline over 10 years (see supplementary Table S2). Other sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results indicated that accounting for interim stroke events (n=146) did not greatly influence the findings. Restricting the analyses to participants with complete cognitive data at all 3 phases (n=4,258) did not qualitatively alter the results. In addition, the association between 10-year risk of stroke and cognitive decline was not modified by APOE ε4.

4. Discussion

In this large cohort of middle-aged men and women, we found higher risk of stroke to be associated with faster decline in multiple cognitive domains assessed using a battery of cognitive tests administered 3 times over 10 years. There was faster decline in phonemic and semantic fluency, vocabulary, and global cognition in the highest risk quartile compared to the referent lowest risk quartile. Our study, based on longitudinal data, provides a less biased estimate of the causal association between stroke risk and cognitive decline than cross-sectional data. The relationship between vascular risk factors and cognition is likely to be bidirectional; cross-sectional data on elderly subjects do not allow the direction of the association to be established. In this study we address whether stroke risk in midlife, when stroke is rare, is associated with more rapid cognitive decline. Our findings add to the literature linking vascular risk to cognitive impairment by providing evidence for the association between stroke risk in midlife and long-term cognitive decline. Using the FSRP as an aggregate measure of risk factors we found that mid to low risk levels on more than one component of the stroke risk score can lead to a threshold of risk that is detrimental to cognitive aging. We found that even in our relatively low risk middle aged population, this led to detectable decline in cognitive performance over ten years. While our data do not allow us to determine an exact cut off for stroke risk that clearly confers a greater risk of cognitive decline, we observed a faster rate of cognitive decline only in the highest risk quartile (FSRP≥6%, mean=9.3%) compared to the referent lowest risk quartile. Thus it appears that in our study sample a stroke risk ≥6% is associated with more rapid cognitive decline.

Among individual risk factors only diabetes was independently associated with cognitive decline. Although this association has not been found in some studies [21], the observed relation between diabetes and cognitive decline in our study is supported by a number of studies reporting associations of diabetes with longitudinal changes on MRI markers of vascular brain injury [17], incident cognitive impairment and cognitive decline [13,36,37], and incident dementia [38]. There is compelling evidence for a causal relationship between alterations in glycemic control and subsequent brain ischemic and atrophic changes [39]. While the absence of an independent association between other risk factors for stroke and cognitive decline may be related to study population attributes (e.g. lower prevalence of risk factors in the present study), it can also substantiate the suggestion that the combined influence or clustering of these risk factors may be particularly important in this association. Indeed stroke risk factors are highly correlated with each other. Overall it appears that FSRP is a good predictor of cognitive impairment and cognitive decline. Our findings further support the notion that stroke risk factors begin to exert their influence on cognition early and that they may act in an additive manner in affecting cognitive decline. Furthermore, although in our study, the differences in rate of cognitive decline between risk groups may seem small, they are nonetheless important from a pathogenetic stand point, especially considering that mean age in our population at stroke risk assessment was only 55 years.

Although the neuropsychological tests used in various studies are not identical, it appears that stroke risk commonly assessed using the FSRP is associated with cognitive function in multiple cognitive domains [7,22–24]. We found that higher stroke risk was associated with decline in all cognitive domains except memory and reasoning. A 3-year follow-up study of 235 healthy older men, showed association between FSRP and decline only on verbal fluency; no associations between FSRP and decline in memory or visual-spatial function were reported [24]. In contrast, in a study of 23,752 stroke free individuals followed for an average of 4 years, higher FSRP score was found to be related to incident cognitive impairment in global cognitive function that focused on memory [21]. Several studies suggest that vascular disease does not always affect memory, and that vascular risk factors may have a particularly detrimental effect on frontally mediated cognitive functions such as verbal fluency [13,40,41]. Deficits in executive function have long been recognized as a salient feature of cognitive impairment of vascular origin. In relation to the FSRP, at least three other cross sectional studies report similar associations between stroke risk and cognitive function. Elias et al, reported associations between higher FSRP and deficits in multiple domains including abstract reasoning and visual-spatial memory, but not verbal memory in 2,175 participants of the Framingham Offspring Study [7]. Seshadri et al found similar associations between FSRP and visual-spatial and executive function but not with verbal memory [23]. These results conflict with another study that found an association between FSRP and both immediate and delayed verbal memory, and semantic verbal fluency [22]. However, it is important to note that comparison of our findings with these studies is limited because of important differences in study methods particularly their cross sectional design.

The mechanisms underlying the association between vascular risk factors and cognitive function remain to be fully elucidated. However, studies suggest that subclinical cerebrovascular disease may present an important link between major risk factors for stroke and cognitive function. These mechanisms include silent cerebral infarctions, brain atrophy and white matter abnormalities [23,42–44]. Hypertension in midlife is associated with accelerated WMHV progression; diabetes and smoking are linked to more rapid increase in temporal horn volume which is a surrogate marker of accelerated hippocampal atrophy. Smoking has also been linked to a marked decrease in total brain volume [17]. The presence of silent brain infarcts on MRI is associated with worse performance on neuropsychological tests and a steeper decline in global cognitive function, memory performance and psychomotor speed [43].

The strengths of our study include its large sample size, three cognitive measures over 10 years to study longitudinal cognitive decline, and use of a representative battery of cognitive tests, permitting examination of different and distinct aspects of cognition. However, there are several limitations. First, since Whitehall II participants were office-based civil servants, they may not be representative of the British population, and thus potentially limiting generalizability of our findings. Second, it is possible that observed associations between stroke risk and cognitive decline are underestimations as our study sample included participants with a more favourable demographic and stroke risk profile than those excluded from the analysis and the general population.

In conclusion, the observed associations between an elevated risk of stroke and long term cognitive decline in multiple cognitive domains, have important implications. Our findings provide some evidence that an aggregation of vascular risk is especially important in this association and suggest that vascular risk assessment may be better determined using a multifactorial risk score. That this association is evident in a relatively young population indicates early neurological consequences of vascular risk factors leading to cognitive decline. Public health implications are in the domain of early prevention and treatment of stroke risk factors in middle age to reduce or forestall cognitive decline and dementia. Dementia is characterized by a long preclinical phase; individuals who later develop dementia may show subtle cognitive changes as early as two decades before diagnosis [45]. Currently there are no specific treatments for cognitive impairment or dementia. Given the important vascular contribution to cognitive impairment, detection and treatment of risk factors particularly at midlife may be most effective in the prevention or progression of cognitive impairment. Indeed, recent projections suggest that up to half of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases might be prevented by risk factor reduction and could potentially prevent up to 3 million AD cases worldwide [46].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating civil service departments and their welfare, personnel, and establishment officers; the British Occupational Health and Safety Agency; the British Council of Civil Service Unions; all participating civil servants in the Whitehall II study; and all members of the Whitehall II study team. The Whitehall II Study team comprises research scientists, statisticians, study coordinators, nurses, data managers, administrative assistants and data entry staff, who make the study possible.

Funding/Support

SK is funded by a doctoral grant from Région Ile-de-France. AS-M is supported by a “European Young Investigator Award” from the European Science Foundation and the National Institute on Aging, NIH (R01AG013196; R01AG034454). MK is supported by the Academy of Finland, the BUPA Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, (R01HL036310; R01AG034454) and the Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None reported

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Desmond DW, Moroney JT, Sano M, Stern Y. Incidence of dementia after ischemic stroke: results of a longitudinal study. Stroke. 2002;33(9):2254–60. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000028235.91778.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamaldo A, Moghekar A, Kilada S, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, O’Brien R. Effect of a clinical stroke on the risk of dementia in a prospective cohort. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1363–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240285.89067.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivan CS, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Kase CS, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Dementia after stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1264–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127810.92616.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1006–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leys D, Henon H, Mackowiak-Cordoliani MA, Pasquier F. Poststroke dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):752–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linden T, Skoog I, Fagerberg B, Steen B, Blomstrand C. Cognitive impairment and dementia 20 months after stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23(1–2):45–52. doi: 10.1159/000073974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias MF, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Elias PK, Beiser A, Au R, et al. Framingham stroke risk profile and lowered cognitive performance. Stroke. 2004;35(2):404–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000103141.82869.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young SE, Mainous AG, III, Carnemolla M. Hyperinsulinemia and cognitive decline in a middle-aged cohort. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(12):2688–93. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu WL, Atti AR, Gatz M, Pedersen NL, Johansson B, Fratiglioni L. Midlife overweight and obesity increase late-life dementia risk: a population-based twin study. Neurology. 2011;76(18):1568–74. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182190d09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64(2):277–81. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyas SL, White LR, Petrovitch H, Webster RG, Foley DJ, Heimovitz HK, et al. Mid-life smoking and late-life dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(4):589–96. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien JT. Vascular cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;14(9):724–33. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000231780.44684.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, Howard G, Liao D, Szklo M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001;56(1):42–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Hanninen T, Laakso MP, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and late-life mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1683–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ. 2001;322(7300):1447–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, Kareholt I, Winblad B, et al. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(10):1556–60. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Palumbo C, et al. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2011;77(5):461–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227b227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofman A, Ott A, Breteler MM, Bots ML, Slooter AJ, van HF, et al. Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9046):151–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachinski V. The 2005 Thomas Willis Lecture: stroke and vascular cognitive impairment: a transdisciplinary, translational and transactional approach. Stroke. 2007;38(4):1396. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260101.08944.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hachinski V. Shifts in thinking about dementia. JAMA. 2008;300(18):2172–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unverzagt FW, McClure LA, Wadley VG, Jenny NS, Go RC, Cushman M, et al. Vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in a stroke-free cohort. Neurology. 2011;77(19):1729–36. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236ef23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Xie J, Huppert FA, Melzer D, Langa KM. Framingham Stroke Risk Profile and poor cognitive function: a population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Elias MF, Au R, Kase CS, et al. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology. 2004;63(9):1591–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142968.22691.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brady CB, Spiro A, McGlinchey-Berroth R, Milberg W, Gaziano JM. Stroke risk predicts verbal fluency decline in healthy older men: evidence from the normative aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(6):340–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.p340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort Profile: the Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(2):251–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: adjustment for antihypertensive medication. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1994;25(1):40–3. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(3):312–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Allan CL, Sexton CE, Jokela M, Virtanen M, et al. Vascular Risk Status as a Predictor of Later-Life Depressive Symptoms: A Cohort Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Mar 16; doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.005. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26 (Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, Glymour MM, Elbaz A, Berr C, Ebmeier KP, et al. Timing of onset of cognitive decline: results from Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:d7622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heim AW. AH4: Group Test of General Intelligence. Windsor United Kingdom: NFER-Nelson Publishing Company, Limited; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borkowski JG, Benton AL, Spreen O. Word fluency and brain damage. Neuropsychologica. 1967;5:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raven JC. Guide to using the Mill Hill vocabulary test with progressive matrices. London, UK: HK Lewis; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh-Manoux A, Akbaraly TN, Marmot M, Melchior M, Ankri J, Sabia S, et al. Persistent depressive symptoms and cognitive function in late midlife: the Whitehall II study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1379–85. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05349gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabia S, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Health behaviors from early to late midlife as predictors of cognitive function: The Whitehall II study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(4):428–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, Coker LH. Fourteen-year longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: the ARIC MRI Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(3):207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Patel B, Tang MX, Manly JJ, Mayeux R. Relation of diabetes to mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(4):570–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrijvers EM, Witteman JC, Sijbrands EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Insulin metabolism and the risk of Alzheimer disease: the Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2010;75(22):1982–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ffe4f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knopman DS, Penman AD, Catellier DJ, Coker LH, Shibata DK, Sharrett AR, et al. Vascular risk factors and longitudinal changes on brain MRI: the ARIC study. Neurology. 2011;76(22):1879–85. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d753f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowler JV. Criteria for vascular dementia: replacing dogma with data. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(2):170–1. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips NA, Mate-Kole CC. Cognitive deficits in peripheral vascular disease. A comparison of mild stroke patients and normal control subjects. Stroke. 1997;28(4):777–84. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C, Au R, Himali JJ, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke. 2010;41(4):600–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den HT, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1215–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Groot JC, de Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, Van GJ, Hofman A, Jolles J, et al. Periventricular cerebral white matter lesions predict rate of cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(3):335–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, D’Agostino RB. The preclinical phase of alzheimer disease: A 22-year prospective study of the Framingham Cohort. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(6):808–13. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819–28. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.