Abstract

Inflammatory biomarkers predict mortality and hospitalisation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Yet, it remains uncertain if biomarkers in addition to reflecting disease severity add new prognostic information on severe COPD. We investigated if leukocytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), and vitamin D were independent predictors of mortality and hospitalisation after adjusting for disease severity with an integrative index, the i-BODE index. In total, 423 patients participating in a pulmonary rehabilitation programme, with a mean value of FEV1 of 38% of predicted, were included. Mean followup was 45 months. During the follow-up period, 149 deaths (35%) were observed and 330 patients (78.0%) had at least one acute hospitalisation; 244 patients (57.7%) had at least one hospitalisation due to an exacerbation of COPD. In the analysis (Cox proportional hazards model) fully adjusted for age, sex, and i-BODE index, the hazard ratio for 1 mg/L increase in CRP was 1.02 (P = 0.003) and for 1 × 109/L increase in leukocytes was 1.43 (P = 0.03). Only leukocyte count was significantly associated with hospitalisation. Vitamin D was neither associated with mortality nor hospitalisation. Leukocytes and CRP add little information on prognosis and vitamin D does not seem to be a useful biomarker in severe COPD in a clinical setting.

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an inflammatory lung disease associated with significant systemic consequences [1]. Several biomarkers have been investigated in search of a better tool to predict clinically relevant outcomes such as mortality, hospitalisation, and exacerbations [2]. Biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and leukocytes represent low-grade systemic inflammation and increased levels have been found in patients with COPD [3] and have been associated with a poor prognosis [4] and comorbidity [5]. Vitamin D on the other hand has anti-inflammatory properties and vitamin D deficiency has been associated with all-cause mortality in the general population [6] and mortality specifically linked to diseases of the respiratory system [7]. Vitamin D deficiency is common in patients with COPD [8], but the prognostic value of vitamin D has only to a lesser extent been investigated in this particular group of patients.

FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) is considered an important and valuable marker of disease severity but is less appropriate to characterise disease activity and predict progression [9]. Despite the clear association between inflammatory biomarkers and COPD, it still remains uncertain whether these biomarkers, like FEV1, only reflect disease severity or whether they add new information in addition to clinical measures of the disease. In order to further investigate this matter, we hypothesised that CRP, leukocytes, and vitamin D were independent predictors of mortality and hospitalisation for COPD exacerbation and that their predictive value would persist after adjusting for disease severity with an integrative index, the i-BODE index. The i-BODE is a modified version of the BODE-index [10]. The original BODE-index has been found to predict risk of mortality [11], hospitalisation [12], and COPD exacerbations [13].

The purpose of the present study was to assess the prognostic value of CRP, leukocytes, and vitamin D level in a cohort of patients with severe COPD referred for outpatient rehabilitation.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of Patients

The patients included in the present study participated in a seven-week pulmonary rehabilitation programme at Hvidovre Hospital, Copenhagen, during the period of May 2005 to March 2011. The main criteria for referral to the rehabilitation programme were stable COPD, FEV1 < 50% of predicted, and MRC (Medical Research Council) dyspnoea scale grade ≥3; nevertheless, all patients were assessed individually in terms of suitability for participation.

2.2. Incremental Shuttle Walking Test (ISWT) and i-BODE Index

ISWT was measured at baseline using the protocol described by Singh et al. [14]. Variables and point allocation used for the computation of the i-BODE index are shown in Table 1 and were validated in a study by Williams et al. [10]. The original BODE index consists of body mass index (BMI), airflow obstruction as measured by FEV1% predicted, functional dyspnoea as measured by the mMRC (modified Medical Research Council) dyspnoea scale, and exercise capacity as measured by the 6-minute walking test [11]. In the i-BODE index, the 6-minute walking test is substituted with the ISWT as a measurement of exercise capacity and the mMRC dyspnoea scale has been replaced with the MRC dyspnoea scale (grades 1–5) [10].

Table 1.

Variables and point allocation used for the computation of the i-BODE index.

| Variable | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 predicted | ≥65 | 50–64 | 36–49 | ≤35 |

| Distance walked on ISWT (m) | ≥250 | 150–249 | 80–149 | <80 |

| MRC dyspnoea grade | 1-2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | >21 | ≤21 |

2.3. Laboratory Measurements

The patients had CRP, leukocytes, and vitamin D measured at the time they entered the rehabilitation programme. All blood samples were analysed at Hvidovre Hospital shortly after they were drawn. The department of Clinical Biochemistry, Hvidovre Hospital, used two different methods for CRP and leukocytes during the study period (2005–2011). Plasma CRP was measured on a Vitros FS 5.1 (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY, USA) during the first half of the study period and on a Cobas 6000 (c501) module (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany), in the second half, both according to the manufacturers' specifications and using proprietary reagents. Leukocytes were counted by using the ADVIA 120 Hematology Analyzer System (Bayer, Holliston, MA, USA) in the first half of the study period and Sysmex XE-5000 (Sysmex Corporation, Japan) in the second half. Measurement of 25(OH)D was conducted by means of a direct, competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay using the DiaSorin LIAISON 25(OH)D Total assay (DiaSorin, Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA). The assay measured both 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D2.

2.4. Mortality and Hospitalisation

The National Health Services Central Register ascertained vital status and provided information on all hospital admissions in the follow-up period up to 24 January, 2012.

A primary diagnosis of COPD (J44.x), or a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure (J96.x) with a secondary diagnosis of COPD (J44.x) at discharge, was recorded as an admission due to exacerbation of COPD. The diagnoses were made according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The Danish Data Inspection Board has approved the present study.

2.5. Statistics

Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify factors that significantly predicted mortality and time to first hospitalisation. Variables included in the model were age, sex, CRP, leukocyte count, vitamin D, FEV1, and i-BODE index score. Assumption of linearity was assessed by categorising the variable into multiple dichotomous variables of equal units (quartiles) on the variable's scale. The results of the regression analyses are given in terms of estimated hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

CRP, leukocyte count, and vitamin D were the variables of interest. They were entered into the model as dichotomous as well as continuous variables, first in a univariate analysis and then in a multivariate analysis adjusting first for age and sex, then age, sex, and FEV1% predicted, and lastly age, sex, and i-BODE index. When smoking status was added to the model, the P values did not change significantly. The cut-off values for the dichotomous values were as follows: CRP < 10 mg/L, leukocytes ≤ 8.8 × 109/L, and vitamin D ≤ 50 nmol/L.

We also combined the dichotomous values into two new variables in which all patients with either two or three biomarkers outside the normal range (the cut-off values are seen above) were grouped. This was similar to the method used in previous studies [15, 16] and was done in order to see if it was possible to identify patients with increased risk of all-cause mortality and hospitalisation.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were created for descriptive purposes using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We used chi-squared test for binary variables and an independent t-test for continuous variables when comparing baseline characteristics of the study population and the excluded population, that is, patients with missing data. The characteristics have been summarised as mean and standard deviation (SD) or percentage. CRP, leukocyte count, and vitamin D have been summarised as median and 25 and 75 percentiles.

3. Results

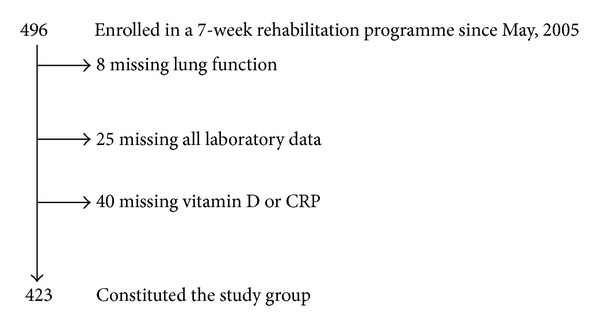

Our study group consisted of 423 consecutive patients as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients included in the study.

In general, most of the patients had severe airflow obstruction; 83.9% of the patients had FEV1 ≤ 50% predicted. Table 2 compares baseline demographics of the study group and patients with missing laboratory tests.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in the study group compared with excluded patients.

| Group of patients | Study group | Excluded | P level |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 423 | 73 | — |

| Females, % | 61.0 | 70.0 | 0.15 |

| Age, years | 68.9 (9.3) | 70.5 (10.2) | 0.18 |

| Pack years | 40.6 (20.8) | 44.7 (23.3) | 0.13 |

| Current smoking, % | 26.8 | 20.5 | 0.26 |

| Heart disease, % | 46.8 | 45.2 | 0.80 |

| Education, years | 8.8 (2.5) | 9.2 (2.7) | 0.25 |

| Lived alone, % | 54.3 | 60.3 | 0.34 |

| Examined in the winter period, % | 75.1 | 77.0 | 0.76 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 37.7 (13.8) | 38.9 (14.9) | 0.55 |

| Prednisolone treatment, % | 3.1 | 6.8 | 0.11 |

| Long-term oxygen therapy, % | 5.0 | 6.8 | 0.51 |

| Oxygen saturation at rest, % | 94.5 (2.1) | 94.4 (2.0) | 0.64 |

| Oxygen desaturation during SWT > 4%, % | 218 (51.5) | 32 (43.8) | 0.22 |

| SWT, metre | 184.5 (95.7) | 180.5 (92.9) | 0.74 |

| MRC dyspnoea score | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.0) | 0.05 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 (6.0) | 26.0 (6.5) | 0.99 |

| Admissions to hospital the previous year1,2,3 | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 2.25) | 0.79 |

| Bed days the previous days1,2,3 | 0 (0, 5.25) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.23 |

| i-BODE index, points | 6 (3) | 5.5 (2.2) | 0.26 |

| Vitamin D, nmol/L2 | 51 (29, 70) | — | — |

| CRP, mg/L2 | 6 (4, 10) | — | — |

| Leukocytes, 109/L2 | 8.7 (7.3, 10.5) | — | — |

1Due to exacerbation of COPD.

2Mean (25, 75) percentiles.

3Mann-Whitney U test.

SWT: Shuttle walking test.

MRC: Medical Research Council.

BMI: body mass index.

In the study group, 208 patients (49.2%) were vitamin D deficient (25(OH)D less than 50 nmol/L), 197 (46.6%) had elevated leukocyte count (above 8.8 × 109/L), and 102 (24.1%) had elevated CRP (above 10 mg/L). In total, 117 (27.6%) had two out of these three biomarkers outside the normal range. Only 38 (9%) had three out of three biomarkers outside the normal range.

Biomarkers were only weakly associated with COPD characteristics such as FEV1. Conversely, CRP and leukocyte count were positively correlated, and CRP was also positively correlated with BMI and negatively correlated with walking distance and desaturation during exercise. CRP was, however, not correlated with the i-BODE index. Leukocyte count was positively correlated with SGRQ (St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire) scores (higher scores indicate more limitations) and prevalence of heart disease.

During the follow-up period, 149 deaths (35.2%) were observed and a total of 330 patients (78.0%) had at least one acute hospital admission for any cause; 244 patients (57.7%) had at least one hospital admission due to an exacerbation of COPD. The hospital admissions for any cause were not dominated by any particular diagnoses.

3.1. Biomarkers and Mortality

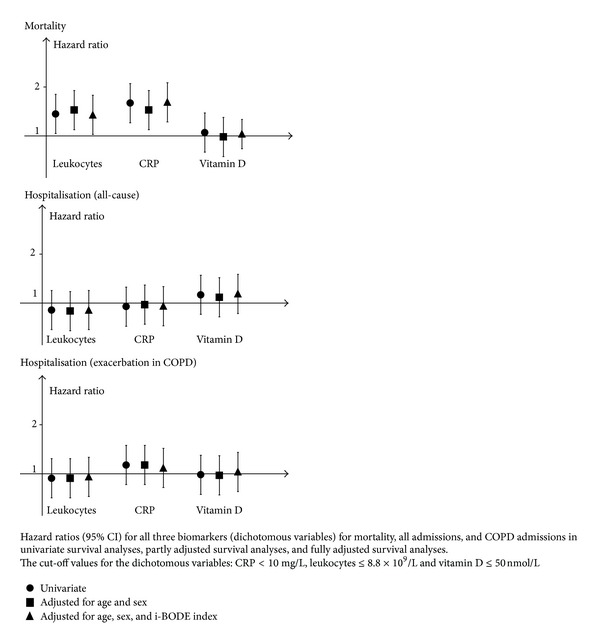

In the univariate analyses of the biomarkers as continuous variables, only CRP was significantly associated with mortality. In the analysis fully adjusted for age, sex, and i-BODE index, the hazard ratio for 1 mg/L increase in CRP was 1.02 (95% CI: 1.01–1.04, P = 0.003). Leukocyte count and vitamin D as continuous variables were not significantly associated with mortality. When entering biomarkers as dichotomous variables in the models, both leukocyte count and CRP were significant predictors of mortality both in the univariate and the adjusted analyses (Figure 2). Two out of three biomarkers outside the normal range predicted mortality both in the univariate and the multivariate analyses with a hazard ratio of 1.48 (95% CI: 1.06–2.08, P = 0.02) and 1.50 (95% CI: 1.07–2.10, P = 0.02), respectively. Three out of three biomarkers outside the normal range did not predict mortality.

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios for leukocytes, CRP, and vitamin D.

3.2. Biomarkers and Hospitalisation

In the univariate analysis, leukocyte count (continuous variable) was significantly associated with hospitalisation. In the analysis fully adjusted for age, sex, and i-BODE index, the hazard ratio for leukocytes was 1.06 (95% CI: 1.02–1.10, P = 0.007) and 1.06 (95% CI: 1.01–1.11, P = 0.018) for hospitalisation due to any cause and hospitalisation due to exacerbation of COPD, respectively. CRP and vitamin D were not significantly associated with hospital admission and neither was the variable of two of three or three out of three biomarkers outside the normal range.

3.3. The i-BODE Index

The i-BODE index was a significant predictor of death and hospitalisation. The hazard ratio for death per one point increase in i-BODE score was 1.35 (95% CI: 1.23–1.49, P < 0.001). The hazard ratio for any acute hospitalisation per one point increase in i-BODE score was 1.16 (95% CI: 1.09–1.23, P < 0.001) and for hospitalisation with an exacerbation of COPD 1.24 (95% CI: 1.15–1.33, P < 0.001). We did not find interaction between variables in the adjusted analysis (age, sex, FEV1, and i-BODE index) and cardiac comorbidity.

4. Discussion

In this study of patients with severe COPD, the prognostic value of three biomarkers was examined. After adjusting for the i-BODE index, we found that elevated leukocyte count was a significant predictor of both mortality and hospital admission, whereas elevated CRP levels only predicted mortality. Vitamin D status and three out of three biomarkers outside the normal range were associated neither with mortality nor hospitalisation. Two out of three biomarkers outside the normal range predicted mortality. As expected, the i-BODE index was a strong predictor of mortality and hospital admission, but none of the investigated biomarkers were associated with the i-BODE score. The results suggest that these biomarkers mostly express disease severity and did not add further information about prognosis in this sample of patients with severe COPD.

Our results regarding leukocytes and CRP are similar to those of previous studies. In the ECLIPSE (Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints) study, the association between leukocytes and mortality in stable COPD was investigated; adjusting for age, previous hospitalisations, and BODE index, leukocyte count was independently associated with mortality [17]. A cross-sectional study of patients with moderate to severe COPD also showed that elevated levels of leukocytes were associated with high resource utilisation in a multivariate analysis [18]. We found that levels of CRP were not associated with the i-BODE index. This is in line with two studies of patients with stable COPD in which the original BODE index was used [19, 20]. In the latter study by Liu et al., CRP and the BODE index were both independent prognostic variables for mortality and it seemed that the combination of the two variables predicted mortality better than either variable alone [20]. In a study using data from the Copenhagen City Heart Study and the Copenhagen General Population Study, the authors concluded that simultaneously elevated levels of high-sensitivity CRP, fibrinogen and leukocytes count in individuals with COPD were associated with increased risk of exacerbation [15]. This was also the case in milder disease and in those without a history of frequent exacerbations implying that the biomarkers added information beyond known clinical parameters. In some subgroups, the risk of exacerbation increased for every additional elevated biomarker. We could not show this additive effect. Most of the individuals in this prospective cohort were GOLD grade I-II and A-B; in contrast, almost all patients in the present study had more severe COPD being GOLD grade III–VI and D–B, as they had been selected for pulmonary rehabilitation. The fact that one of the biomarkers, vitamin D, did not have any predictive value also has to be taken into consideration.

The association between CRP and mortality was not very strong in our material, but in other studies CRP has been associated with mortality in patients with mild to moderate COPD [4, 21, 22]. This association could not be reproduced in patients with moderate to severe COPD [23], and even though the level of CRP is increased in patients with COPD compared with controls [24], it is an unspecific acute phase reactant and displays a wide variability in stable subjects with COPD over three months [25], which makes it less appropriate as a prognostic marker in this stratum of COPD.

We did not find that vitamin D predicted mortality in patients with COPD. This is in concordance with a recent prospective study in which 462 patients with moderate to very severe COPD were followed for 10 years [26]. However, several observational studies have shown that low vitamin D status predicts poor survival in the general population and non-COPD patients [6, 27, 28]. Intervention studies are called for as vitamin D deficiency is frequent in patients with severe COPD [8, 29] and has also been associated with low FEV1 [30] and respiratory tract infections [31]. Nevertheless, no effect of vitamin D supplementation was seen in COPD exacerbations in a randomised controlled study by Lehouck et al. except in a subgroup of patients with vitamin D status <10 ng/mL (25 nmol/L) [32]. Vitamin D levels may be low in patients with COPD and in general in patients with noncommunicable diseases [33], but it seems that vitamin D deficiency is not a major contributor to disease mechanisms or prognosis. Vitamin D deficiency may only be a marker of poor health in general but not specifically in COPD.

The patients in our study were well characterised and no patients were lost during followup; the patient cohort was very homogeneous because of the inclusion criteria for the rehabilitation programme. A weakness of the study was that we did not know whether the patients had been supplemented with vitamin D or not. We did not measure high-sensitivity CRP; however, regular CRP is readily available for everyone in daily clinical practice.

The main clinical implication of our finding is that even though epidemiological studies show that CRP and leukocytes may have a prognostic value in mild to moderate COPD, clinical characterisation of patients with severe COPD is often sufficient for prediction of clinical prognosis. None of the biomarkers seem to reflect disease activity. Leukocyte count and CRP add only little information on prognosis and vitamin D does not appear to be a useful biomarker in severe COPD.

Acknowledgment

Mia Moberg was funded by TrygFonden.

Conflict of Interests

The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Agusti AGN. COPD, a multicomponent disease: implications for management. Respiratory Medicine. 2005;99(6):670–682. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. Biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Translational Research. 2012;159(4):228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan WQ, Man SFP, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59(7):574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahl M, Vestbo J, Lange P, Bojesen SE, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. C-reactive protein as a predictor of prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175(3):250–255. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-713OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomsen M, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory biomarkers and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;186(10):982–988. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1113OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, Astor B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(15):1629–1637. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skaaby T, Husemoen LL, Pisinger C, et al. Vitamin D status and cause-specific mortality: a general population study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052423.e52423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssens W, Bouillon R, Claes B, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in COPD and correlates with variants in the vitamin D-binding gene. Thorax. 2010;65(3):215–220. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.120659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vestbo J, Rennard S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease biomarker(s) for disease activity needed—urgently. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;182(7):863–864. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0602ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JEA, Green RH, Warrington V, Steiner MC, Morgan MDL, Singh SJ. Development of the i-BODE: validation of the incremental shuttle walking test within the BODE index. Respiratory Medicine. 2012;106(3):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(10):1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong K-C, Earnest A, Lu S-J. A multidimensional grading system (BODE index) as predictor of hospitalization for COPD. Chest. 2005;128(6):3810–3816. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Casanova C, et al. Prediction of risk of COPD exacerbations by the BODE index. Respiratory Medicine. 2009;103(3):373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S, Walters D, Hardman AE. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax. 1992;47(12):1019–1024. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.12.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomsen M, Ingebrigtsen T, Marott J, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(22):2353–2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agusti A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037483.e37483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celli BR, Locantore N, Yates J, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers improve clinical prediction of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;185(10):1065–1072. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1792OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Polo C, Alcazar-Navarrete B, Ruiz-Iturriaga LA, et al. Factors associated with high healthcare resource utilisation among COPD patients. Respiratory Medicine. 2012;106(12):1734–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaki E, Kontogianni K, Papaioannou AI, et al. Associations between BODE index and systemic inflammatory biomarkers in COPD. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2011;8(6):408–413. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.619599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S-F, Wang C-C, Chin C-H, Chen Y-C, Lin M-C. High value of combined serum C-reactive protein and BODE score for mortality prediction in patients with stable COPD. Archivos de Bronconeumologia. 2011;47(9):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Man SF, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, Wise RA, Tashkin DP, Sin DD. C-reactive protein and mortality in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61(10):849–853. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.059808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Torres JP, Cordoba-Lanus E, López-Aguilar C, et al. C-reactive protein levels and clinically important predictive outcomes in stable COPD patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2006;27(5):902–907. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00109605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Torres JP, Pinto-Plata V, Casanova C, et al. C-reactive protein levels and survival in patients with moderate to very severe COPD. Chest. 2008;133(6):1336–1343. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karadag F, Kirdar S, Karul AB, Ceylan E. The value of C-reactive protein as a marker of systemic inflammation in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008;19(2):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickens JA, Miller BE, Edwards LD, Silverman EK, Lomas DA, Tal-Singer R. COPD association and repeatability of blood biomarkers in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respiratory Research. 2011;12, article 146 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmgaard DB, Mygind LH, Titlestad IL, et al. Serum vitamin D in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease does not correlate with mortality—results from a 10-year prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053670.e53670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutchinson MS, Grimnes G, Joakimsen RM, Figenschau Y, Jorde R. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are associated with increased all-cause mortality risk in a general population: the Tromsø study. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2010;162(5):935–942. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginde AA, Scragg R, Schwartz RS, Camargo CA., Jr. Prospective study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in older U.S. adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(9):1595–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ringbaek T, Martinez G, Durakovic A, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who participate in pulmonary rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2011;31(4):261–267. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31821c13aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pulmonary function in the third national health and nutrition examination Survey. Chest. 2005;128(6):3792–3798. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA., Jr. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(4):384–390. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehouck A, Mathieu C, Carremans C, et al. High doses of vitamin D to reduce exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156(2):105–114. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality—a review of recent evidence. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2013;12(10):976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]