Abstract

Identification of edible mushrooms particularly Pleurotus genus has been restricted due to various obstacles. The present study attempted to use the combination of two variable regions of IGS1 and ITS for classifying the economically cultivated Pleurotus species. Integration of the two regions proved a high ability that not only could clearly distinguish the species but also served sufficient intraspecies variation. Phylogenetic tree (IGS1 + ITS) showed seven distinct clades, each clade belonging to a separate species group. Moreover, the species differentiation was tested by AMOVA and the results were reconfirmed by presenting appropriate amounts of divergence (91.82% among and 8.18% within the species). In spite of achieving a proper classification of species by combination of IGS1 and ITS sequences, the phylogenetic tree showed the misclassification of the species of P. nebrodensis and P. eryngii var. ferulae with other strains of P. eryngii. However, the constructed median joining (MJ) network could not only differentiate between these species but also offer a profound perception of the species' evolutionary process. Eventually, due to the sufficient variation among and within species, distinct sequences, simple amplification, and location between ideal conserved ribosomal genes, the integration of IGS1 and ITS sequences is recommended as a desirable DNA barcode.

1. Introduction

Pleurotus genera (Pleurotaceae, Agaricales, and Basidiomycetes) also known as oyster mushrooms are worldwide distributed macrofungi [1] that comprise various kinds of highly priced edible mushrooms [2]. Edible mushrooms are also a complete source of nutrition. They are known for their high levels of fibers, carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins, vitamins, and many other minerals [3].

To date, identification of edible mushrooms particularly Pleurotus genus has been constrained due to various factors. Cultivated edible mushrooms that belong to the Pleurotus genus have been principally discriminated by their morphological features such as shape, colour and size of hymenophore, length, thickness and colour of stipe, yield, and duration for maturation [4]. However, the notion of species differentiation based on environmental factors can be unreliable and lead to misidentification as well as erroneous taxonomic conclusions [5]. Moreover, the number of fungal species that can be classified easily by morphological factors is not considerable [6].

Even in a country like Malaysia which has a vast diversity of mushrooms and where the medicinal and dietary properties of various edible fungi are widely known [7], not many studies have been conducted that concentrate on the phylogenetic relationships and discrimination of cultivated edible fungi, particularly by using molecular methods.

The advantages of identification are obvious. All cultivated varieties of fungi can face loss of genetic diversity and inbreeding effects [8] that force farmers to introduce new hybrids in their farms. The biggest concern would be of adaptation of new lines to the new environment and of tracking lines that remain stable in various environmental parameters. Classification of mushroom species and genus through the introduction of cultivated line transfers across farms and also between Asian countries could also be a challenge as the demand of this genus is rapidly expanding.

Moreover, classification of fungal species using DNA barcodes is a reliable and effective tool and it can be implemented at any period of hyphal development. With the appearance of DNA based molecular methods, several molecular techniques, including SSR [9], RAPD [10], AFLP [8], and the sequences of mitochondrial SSU rRNA [11], cytochrome oxidase genes [12, 13], and partial EF1α and RPB2 gene [14] have been used to validate mushroom species. The existing investigations have no doubt assisted in fungal identification; however, some of the reports could not accurately categorize the fungi genera, particularly intraspecies of Pleurotus.

Up to the present, numerous studies demonstrated that internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 regions [15] possessed a great potential to distinguish between species of fungi [16–18]. According to Schoch et al. [18], ITS region has the highest probability of successful identification for the broadest range of fungi, with the most clearly defined divergence level between inter- and intraspecific variation. However, a number of previously reported studies demonstrated that ITS is not a powerful tool to distinguish many closely related fungal species [19, 20] as well as intragenus [5, 6]. Although there are thoughts in inefficiency of this marker, Schoch and Seifert [21] still believe that ITS as a DNA barcode provides the best possible path to achieve this goal in fungi.

The intergenic spacer (IGS) regions are two noncoding and highly variable DNA units [22] that are located between conserved sequences of 25S, 5S, and 18S within the nuclear rRNA gene [23]. IGS1 is normally shorter than IGS2 and can be easily used for discriminating strains of the uncultured species [24]. However, only a limited number of studies have focused on IGS region as a systematic tool for species delimitation of the commonly cultivated edible mushrooms.

According to Dupuis et al. [25], it has been shown that all marker groups have relatively equal success in delineating closely related species and that using more markers increases average delimitation success. Hence, this study aimed (i) to develop new pairs of primer for amplification and sequencing of two highly variable regions of intergenic spacer (IGS) 1 and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1 and 2, (ii) to investigate the molecular phylogeny and taxonomic relationships of common cultivated species of Pleurotus using variation at the IGS1 and ITS regions of nuclear ribosomal DNA, and (iii) to assess the ability of combined IGS1 and ITS regions as DNA barcode.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungi and Culture Preparation

The experimental fungal samples were mainly collected from several Malaysian mushroom farms and some obtained from the Fungal Biotechnology Laboratory, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya. Strains and species used in this study (Table 1) were morphologically identified using taxonomic keys by the Mushroom Research Centre (MRC), University of Malaya. Axenic dikaryon cultures were prepared by transferring a piece of tissue from the context of the fruit body to a potato dextrose agar (PDA) plate. The Petri dishes were incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 14 days.

Table 1.

Strains and species used in this study and the GenBank accession numbers.

| Strain(s) | Species | Location | Product length (bp) | GenBank (NCBI) accession number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGS1 | ITS1&2 | IGS1 | ITS1&2 | |||

| FPPMK-L |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

Local strain (Reishi Lab Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 530 | 660 | JX271874 | JX429930 |

| FPPMB-L |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

Local strain (Damansara Mushroom Industry) |

Malaysia | 530 | 660 | JX271878 | JX429931 |

| FPPNA-L |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

Local strain (NAS Agro Farm) |

Malaysia | 530 | 660 | JX271879 | JX429932 |

| FPPMC-L |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

Local strain (GanoFarm Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 530 | 660 | JX271880 | JX429933 |

| FPPMK-P |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

PL27 (Reishi Lab Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 530 | 660 | JX271881 | JX429934 |

| FPPMB-T |

Pleurotus pulmonarius

Thai strain (Damansara Mushroom Industry) |

Malaysia | 531 | 660 | JX271889 | JX429935 |

| FPCMC |

Pleurotus citrinopileatus

(GanoFarm Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 527 | 666 | JX271882 | JX429936 |

| FPFMK |

Pleurotus floridanus

(Reishi Lab Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 527 | 668 | JX271884 | JX429937 |

| FPOPT-1 |

Pleurotus ostreatus

Gift from Mycobiotech |

Singapore | 543 | 669 | JX271885 | JX429938 |

| FPOPT-2 |

Pleurotus ostreatus

Gift from Mycobiotech |

Singapore | 543 | 669 | JX271886 | JX429939 |

| FPSPT |

Pleurotus sapidus

Gift from Institute of Edible Mushroom (Shanghai, China) |

China | 527 | 668 | JX271888 | JX429940 |

| FPAB |

Pleurotus cystidiosus

(GanoFarm Sdn. Bhd.) |

Malaysia | 530 | — | JX271891 | — |

| FPEK-1 |

Pleurotus eryngii

(Obtained from supermarket, imported from Thailand) |

Thailand | 548 | 668 | JX271883 | JX429941 |

| FPEK-2 |

Pleurotus eryngii

(Obtained from supermarket, imported from China) |

China | 548 | 668 | JX271887 | JX429942 |

2.2. DNA Extraction

Mycelia were directly scraped (50 mg) from the surface of the solid medium. Sterilized quartz (50 mg) and sufficient 2% SDS buffer were added to the samples [26]. The samples were then incubated for 45 minutes at 58°C. After homogenization and cell lysis steps, the tubes were centrifuged at 16000 ×g for 10 minutes. Next, the samples were extracted twice using CHCl3 : isoamyl alcohol (24 : 1). After precipitation, the DNA pellet was dissolved in 50 μL of TE buffer and maintained in −20°C for further analysis.

2.3. Primer Design

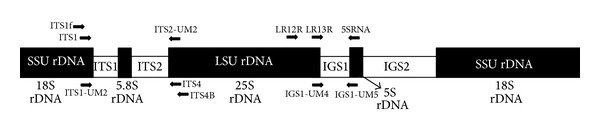

Two previously reported primers of LR12R and LR13R (as forward) and one primer of 5SRNA (as reverse) [27, 28] were employed to recover the nucleotide sequence of partial large subunit rRNA (25S), complete intergenic spacer 1 (IGS1), and partial 5SrRNA (Table 2). Moreover, four previously published primers of ITS1 and ITS1f (as forward), and ITS4 and ITS4B (as reverse) [15, 29] were used to recover the nucleotide sequences of partial 18S, complete internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1, 5.8S, internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 2, and partial 28S (Table 2). Briefly, the obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA4.0 software [30], and the conserved regions were detected by DNAsp v. 5.0 [31]. The new pairs of primer were designed with NCBI Primer-BLAST [32, 33]. The structure of the ribosomal RNA in Pleurotus genus and the orientation and location of the used PCR primers, including published and unpublished, are schematically shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

List of designed and referenced PCR primers used in this study.

| Primer ID | Type | Sequence | T m | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR12R | Forward | 5′-CTGAACGCCTCTAAGTCAGAA-3′ | 53°C | — |

| LR13R | Forward | 5′-GCATTGTTGTTCCGATG-3′ | 53°C | — |

| 5SRNA | Reverse | 5′-ATCAGACGGGATGCGGT-3′ | 53°C | — |

| ITS1 | Forward | 5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′ | 55°C | — |

| ITS1f | Forward | 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′ | 57°C | — |

| ITS4 | Reverse | 5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′ | 55°C | — |

| ITS4B | Reverse | 5′-CAGGAGACTTGTACACGGTCCAG-3′ | 57°C | — |

| IGS1-UM4 | Forward | 5′-AGTAAACTGACTTCAATTTCCGAGC-3′ | 55°C | 40 |

| IGS1-UM5 | Reverse | 5′-ATCCGCTGAGGTTAAGCCCT-3′ | 55°C | 55 |

| ITS1-UM2 | Forward | 5′-TAACAAGGTTTCCGTAGGTG-3′ | 55°C | 45 |

| ITS2-UM2 | Reverse | 5′-CTTAAGTTCAGCGGGTAGTC-3′ | 55°C | 50 |

Figure 1.

Primer binding sites used to amplify IGS1 and ITS regions. The arrowheads show the 3′ end of each primer. LSU rDNA represents the large subunit ribosomal DNA and LSU rDNA represents the small subunit ribosomal DNA.

2.4. PCR Amplification Protocol

The amplification of IGS1 region was performed in a reaction volume of 50 μL using a thermocycler. The reaction mixture contained 100 ng (0.5 μL) of template DNA, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.3 μM of each primer, 0.25 mM of each dNTPs, adequate amount of 5x Taq buffer, and 2 units of GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega). The cycling parameters were initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes; followed by 28 cycles including denaturation at 94°C, annealing at 54°C, and extension at 72°C for 40 seconds; and finalized by extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. In order to observe the amplicons by gel documentation system, PCR products were loaded in 1.2% agarose gel, followed by electrophoresis separation, and then stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr).

2.5. Purification of PCR Product and Alignment

NucleoSpin Extract II Kit (Chemopharm) was used to purify the PCR products. Amplicons were sequenced in both reverse and forward directions by an ABI 3730XL automated sequencer [34]. Revision of chromatograms was performed by Chromas Lite v. 2.01 program (http://technelysium.com.au/?page_id=13). Sequences were then aligned using MEGA 4.0 software [30]. Using the new BankIt submission tool, depositing of sequences in the GenBank (National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)) was carried out (the accession numbers are shown in Table 1). Through a BLAST search, eight highly homologous sequences of IGS1 and seven of ITS regions were retrieved from GenBank as references material (Table 3).

Table 3.

The reference sequences used in this study, downloaded from NCBI GenBank.

| IGS1 | ITS1&2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank ID | Species | Location | GenBank ID | Species | Location |

| AB234042 | P. eryngii | Japan | AB286173 | P. eryngii | Japan |

| AB234045 | P. eryngii | Japan | AB286174 | P. eryngii | Japan |

| AB234047 | P. eryngii | Japan | AY315805 | P. cystidiosus | Japan |

| AB286142 | P. eryngii | Japan | HM561973 | P. ostreatus | Singapore |

| AB286124 | P. eryngii var. ferulae | Japan | AB286159 | P. eryngii var. ferulae | Japan |

| AY463034 | P. nebrodensis | China | EU424308 | P. nebrodensis | China |

| AB234031 | P. pulmonarius | Japan | AB115050 | P. pulmonarius | Japan |

| AB234030 | P. ostreatus | Japan | — | — | — |

2.6. Phylogenetic and Statistical Analyses

The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) method was used to construct the phylogenetic trees. Bootstrap phylogeny analysis was done with 1000 replications to statistically test the trees. The pairwise genetic distances were calculated by maximum composite likelihood method using MEGA 4.0 program [30]. DNAsp v. 5.10.00 software was employed to compute haplotype data file [31]. To estimate the significance of variance within and among the species and to quantify the extension of families and species differences, the AMOVA (analysis of molecular variance) was calculated by Alrequin v. 3.50 program [35]. The Network ver. 4.6.0.1 software (http://www.fluxus-engineering.com/) was implemented to estimate phylogenetic relationships among the unique haplotypes. This was achieved by constructing a genealogical network tree and the median joining (MJ) algorithm [36].

3. Results

At first, new pairs of primer for amplification and sequencing of two highly variable regions of intergenic spacer (IGS) 1 and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1 and 2 were designed (Table 2). The potential of integration of IGS1 and ITS regions as inter- and intraspecies marker was examined. The efficiency of three conserved regions including IGS1, ITS, and a combination of IGS1 and ITS sequences was compared. Several parameters were individually computed for each region (Table 4). Three conserved regions were separately detected for each region (1: 126–227, 2: 355–400, and 3: 430–491 (IGS1) and 1: 1–111, 2: 363–466, and 3: 623–702 (ITS 1 and 2)).

Table 4.

Proposed features of IGS1, ITS, and the combination of IGS1 and ITS regions computed in the current study.

| Region | Number of sequences considered | Variation among population (%) | Variation within population (%) | Conserved sites | Variable sites | Parsimony informative sites | Singleton sites | Total number of haplotypes | Overall mean distance (diversity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGS1 | 22 | 88.98 | 11.02 | 512/555 92.25% |

42/555 7.57% |

30/555 5.41% |

12/555 2.16% |

14 | 0.019 |

| ITS1&2 | 19 | 92.73 | 7.27 | 447/704 63.49% |

239/704 33.95% |

105/704 14.91% |

124/704 17.61% |

12 | 0.043 |

| IGS1 + ITS1&2 | 21 | 91.82 | 8.18 | 958/1259 76.09% |

282/1259 22.40% |

141/1259 11.20% |

131/1259 10.41% |

16 | 0.051 |

Secondly, by use of the same samples, the IGS1 and ITS regions gave rise to 14 and 12 unique haplotypes, respectively. However with the integration of IGS1 and ITS, the number of haplotypes rose to 16, which demonstrated that the combination of IGS1 and ITS regions yielded higher intraspecies variation (Table 4). Thus this integration would be a good benchmark for resolving the molecular phylogeny and taxonomic relationships of common cultivated species of Pleurotus. The potential of these regions was further tested using various statistical tests. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) of IGS1 sequences revealed lower percentage of variation within the samples compared to among the samples (among: 88.98%; within: 11.02%). However, AMOVA of ITS sequences showed lower variation within the species (7.27%) and high divergence among the species (92.73%). In contrast, the combination of IGS1 and ITS regions fulfilled the prerequisite of being a potential marker by demonstrating 91.82% of variation among and 8.18% within the sequences (Table 4).

Thirdly, to recommend an efficient sequence-based DNA barcode for Pleurotus genus, the combined IGS1 and ITS regions were used. The potential of this integrated sequence was then demonstrated by various statistical analyses. Population pairwise FST (spatial genetic differentiation) P values based on IGS1 sequences were calculated for eight groups of species including P. cystidiosus (1), P. eryngii (2), P. nebrodensis (3), P. ostreatus (4), P. pulmonarius (5), P. floridanus (6), P. sapidus (7), and P. citrinopileatus (8). There was no significant difference among P. floridanus, P. citrinopileatus and P. sapidus as well as P. nebrodensis, P. eryngii var. ferulae and P. eryngii. Moreover, these results were confirmed by the exact test of sample nondifferentiation based on haplotype frequencies (P ≤ 0.05). In contrast, the significant differences among the groups of P. floridanus, P. citrinopileatus, and P. sapidus were obtained by integration of IGS1 and ITS regions. In addition, higher FST and differentiation P values among P. nebrodensis, P. eryngii var. ferulae, and P. eryngii were observed.

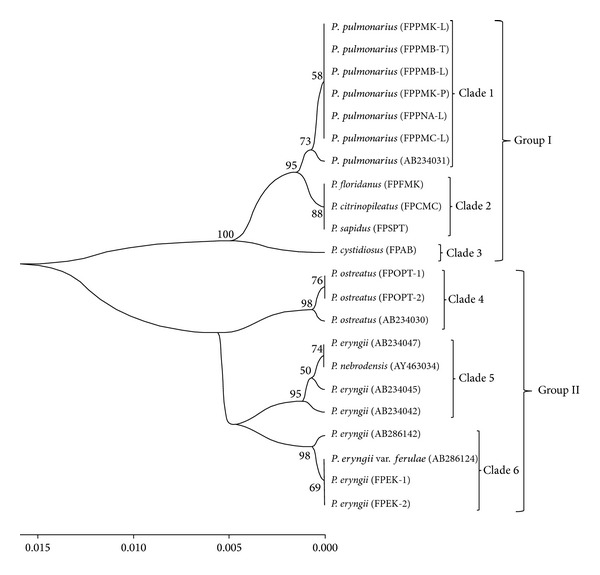

Homology search analysis by NCBI BLAST was performed for IGS1 sequences and eight published sequences which had great similarity with the experimental strains which were detected. The most homologous sequences taken from the BLAST search were included in the current study as references, P. pulmonarius (AB234031-Japan); P. ostreatus (AB234030-Japan); P. eryngii (AB234047-Japan); P. nebrodensis (AY463034-China); P. eryngii (AB234045-Japan); P. eryngii (AB234042-Japan); P. eryngii (AB286142-Japan); P. eryngii var. ferulae (AB286124-Japan). However, through our BLAST search, the reference sequences were only found for the species of P. eryngii, P. pulmonarius, and P. ostreatus and there was no record for the sequences of P. sapidus, P. floridanus, P. cystidiosus, and P. citrinopileatus, meaning that the sequences obtained in this study had been deposited to NCBI GenBank for the first time. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the sequences of IGS1 from our study (Table 1) in addition to the above-mentioned GenBank material (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree constructed based on IGS1 sequences of experimental samples using UPGMA method. The sequences of AB234031 (P. pulmonarius); AB234030 (P. ostreatus); AB234045, AB234042, AB286142, and AB234047 (P. eryngii); AY463034 (P. nebrodensis); and AB286124 (P. eryngii var. ferulae) were downloaded from NCBI GenBank. Numbers close to branches indicate 1000 replication of bootstrap test and the codes refer to sample ID.

In addition to the IGS1 sequences, BLAST search analysis was performed for ITS sequences by NCBI BLAST. Eight sequences which had great similarity were downloaded from NCBI GenBank (HM561973 (P. ostreatus), AB115050 (P. pulmonarius), AB286159 (P. eryngii var. ferulae), AB286173 and AB286174 (P. eryngii), EU424308 (P. nebrodensis), and AY315805 (P. cystidiosus)).

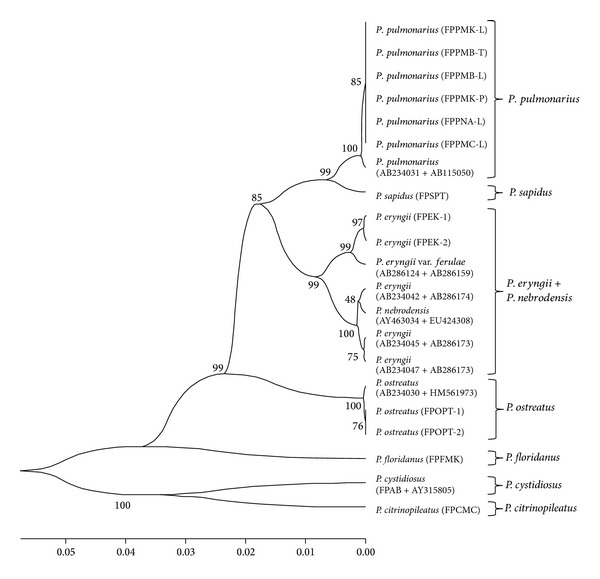

The obtained sequences of IGS1 and ITS regions in addition to those previously deposited into GenBank were employed to construct a combined phylogenetic tree. The constructed UPGMA tree by solely IGS1 sequences separated the samples into two main groups of species which was not desirably able to classify the species (Figure 2). However, the construction of a phylogenetic tree based on integration of IGS1 and ITS sequences resulted in a confident taxonomic conclusion. In total, the bootstrap values obtained in IGS1 tree were lower than the combination of two regions (Figures 2 and 4). At the first clade of both trees, P. pulmonarius members presented high homology with the previously deposited sequences of P. pulmonarius (AB234031 and AB115050 from Japan) [23]. The phylogenetically different species of P. floridanus (FPFMK), P. citrinopileatus (FPCMC), and P. sapidus (FPSPT) that were wrongly categorized in a single clade by IGS1 sequences could clearly be distinguished by integration of IGS1 and ITS sequences. Another distinct achievement of combined IGS1 and ITS regions compared to solely IGS1 was the provision of more precise classification and discrimination of P. eryngii, P. eryngii var. ferulae, and P. nebrodensis (Figure 4). Other evaluated species and strains were clearly distinguished by the combined IGS1 and ITS phylogenetic tree. Moreover, the experimental species and strains were confirmed by additional material which were downloaded from the NCBI GenBank and supported by high bootstrap values.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree constructed by the combination of IGS1 and ITS sequences using UPGMA method. The IGS1 sequences of AB234031 (P. pulmonarius); AB234030 (P. ostreatus); AB234045, AB234042, and AB234047 (P. eryngii); AY463034 (P. nebrodensis); and AB286124 (P. eryngii var. ferulae) as well as ITS sequences of HM561973 (P. ostreatus); AB115050 (P. pulmonarius); AB286159 (P. eryngii var. ferulae); AB286173 and AB286174 (P. eryngii); EU424308 (P. nebrodensis); and AY315805 (P. cystidiosus) were downloaded from NCBI GenBank. Numbers close to branches indicate 1000 replications of bootstrap test and codes represent the sample ID.

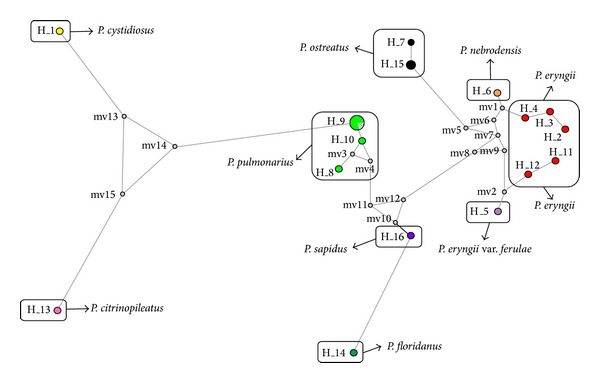

The relationships between combined IGS1 and ITS haplotypes were profoundly assessed by constructing the genealogical medianjoining network (Figure 3). Results obtained showed that 16 haplotypes belonged to eight species and one variety could clearly be distinguished. According to the network tree, haplotype 1 (H_1 : P. cystidiosus) and H_13 (P. citrinopileatus) were segregated from the other species by a number of mutations. H_1, H_13, and H_9 (P. pulmonarius) were connected together by 3 median vectors (13, 14, and 15). Median vectors (MV) obtained in this study can demonstrate an extinct ancestral strain or possible extant unsampled sequences [37, 38]. A distinct outcome that made MJ network analysis superior than phylogenetic tree emerged when a greater discrimination of P. pulmonarius members was demonstrated. H_8 (P. pulmonarius, AB234031 + AB115050) was connected to H_10 (P. pulmonarius, Thai strain) by mv3, and H_10 consequently linked to H_9 (P. pulmonarius, local strains) by a mutation. However, PL27 which is one of the available local strains of P. pulmonarius in Malaysia could not be distinguished and located in H_9 (indicated by a parallel hatched pattern). This can prove that PL27 may be an inbreed hybrid of local strain or originated from the same location. The positions of P. sapidus, P. floridanus, and P. ostreatus were clearly illustrated. Other distinct evidence that made network analysis more effective than phylogenetic tree appeared where H_5 (P. eryngii var. ferulae) and H_6 (P. nebrodensis) could be discriminated by mv2 and mv1, respectively (Figure 3). However, according to the combined IGS1 and ITS phylogenetic tree, the position of these species was not clearly observed (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The median joining haplotype network of the combined IGS1 and ITS sequences. H and MV indicate haplotype and median vector, respectively.

4. Discussion

The identification of precise taxonomic position of species is essential when selection programs are being employed for any new strain developmental experiments as well as for any newly designed mushroom breeding programs. As for domestication and hybridization breeding, the intra- and interspecies information is highly valuable. ITS region will be a useful marker for interspecies information that allows farmers to recognize the species of interest for crossbreeding, hybrid vigour, and minimizing of inbreeding effects. Farmers can then have records of movement of species within and between farms. This will give farmers an opportunity not to arrive at an erroneous conclusion by recognizing the targeted species as an incorrect species [39, 40]. As noted earlier, a number of molecular based markers have been hitherto employed to investigate phylogenetic relationship and taxonomic hierarchy of the edible mushrooms, particularly Pleurotus genus [9, 41]. However, many such studies on fungal strain identification have been performed by common morphological characteristics [5, 11] which were unreliable and misleading [42, 43].

The current study revealed that P. pulmonarius was placed in a distinct clade with the P. pulmonarius strains referenced from NCBI GenBank (AB234031 + AB115050 from Japan) [23]. Based on the study done by Fries [44], this species nominated as L. sajor-caju was later renamed as P. sajor-caju by Singer [45]. However, based on morphological traits and microscopic comparisons done by Pegler and Yi-Jian [46], it was proposed that L. sajor-caju should not be categorized as P. sajor-caju. Another study done by Li and Yao [47] based on molecular and morphological data led to the findings and agreement that the scientific name of this species is P. pulmonarius. However, the most recent report done by Shnyreva et al. [48] confirmed that P. sajor-caju and P. pulmonarius are two separate species. The present study revealed that the available reference sequences identified as P. pulmonarius in the NCBI database, in accordance with taxonomic classification, suggested that the strains used in this study may relate to P. pulmonarius.

The phylogenetic tree based on integration of IGS1 and ITS regions assisted towards the proper classification of species and strains (Figure 4). However, the solely implemented IGS1 sequences resulted in a tree which compiled three distinct species of P. floridanus, P. citrinopileatus, and P. sapidus in one clade (Figure 2). Moreover, the IGS1 tree was not able to distinguish species of P. nebrodensis and P. eryngii var. ferulae from P. eryngii. In addition to the ambiguities generated by using single IGS1, prior studies on other molecular markers have also pointed out various ambiguities. Great similarity was reported between P. pulmonarius and P. eryngii (96% bootstrap support) as well as between P. sapidus and P. colombinus (100% bootstrap support) by Gonzalez and Labarère [11]. However, Zervakis et al. [49] and Iracabal et al. [50] disclosed a close relationship between P. ostreatus and P. colombinus and P. eryngii and P. cystidiosus. In total, the positions of P. pulmonarius, P. sapidus, P. sajor-caju, P. colombinus, P. eryngii, P. flabellatus, and P. cystidiosus have remained ambiguous and some of these species have been wrongly grouped together in the same branch [11]. However, the acquired phylogenetic tree based on combined sequences of IGS1 and ITS regions provided such variation within and among species that could clearly delimit the examined species and strains.

In the present study, desirable AMOVA results were achieved when IGS1 and ITS sequences of the examined samples were combined. The combined regions gave better genetic differentiation among and within species with a high genetic variation of 91.82% and 8.18%, respectively (Table 4).

Though the parsimony network analysis can deliver a better understanding of the relationships within the genus, based on the precise literature, no record was found to show the use of this analysis for Pleurotus genus. In spite of achieving a proper classification of species by integration of IGS1 and ITS sequences, the phylogenetic tree showed the misclassification of the species of P. nebrodensis and P. eryngii var. ferulae with other strains of P. eryngii. In contrast, the median joining network could differentiate between the above-mentioned species (Figure 3). Moreover, P. pulmonarius (H_10) which was previously grouped together with P. pulmonarius (H_9) by phylogenetic tree proved to be distinguishable by MJ network analysis. Hence, by employment of the MJ network tree as well as combination of IGS1 and ITS regions, the experimental species and strains used in the present study were properly discriminated.

According to Meyer and Paulay [51], two principal elements are proposed in DNA barcoding: (1) the ability to assign an unknown sample to a known species and (2) the ability to detect previously unsampled species as distinct. This study proved that the combination of ITS and IGS regions with demonstrating simple amplification, location between conserved ribosomal genes, and adequate divergence levels (among and within populations) can be employed as a fungal DNA barcode. Moreover, according to Gilmore et al. [52], Nguyen and Seifert [12], and Vialle et al. [53], DNA barcoding and sequence-based molecular identification are known to be a small and standardized DNA fragment which could be amplified simply. However, the amplification and combination of IGS1 and ITS regions in this study required extra work and also the obtained fragments were not small and standard (>1.1 kb). Furthermore, the prospect of assigning an unknown to a known is promising especially for well-known, comprehensively sampled groups [51]. Moreover, according to Dupuis et al. [25], it has been shown that all marker groups have relatively equal success in delineating closely related species and that using more markers increases average delimitation success. Thus, in order to discover a consensus and powerful DNA barcodes for identification of fungal strains and species, this study suggests that more comprehensive sampled groups should be employed and/or new regions and molecular markers should be developed and consequently a comparison study should be conducted.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the potential of the integration of IGS1 and ITS sequences of common cultivated Pleurotus species as an efficient inter- and intraspecies DNA marker. This marker could be used as a sequence-based DNA barcode because it presented sufficient variation among and within species, distinct sequences, simple amplification, and location between ideal conserved ribosomal genes. However, this study suggests that new molecular markers should be developed which can easily be employed for identification of the Pleurotus genus. Moreover, due to nonavailability of comprehensive sampled groups, we suggest examination of this highly variable marker with a greater sample size. The analyses used in the current study such as the medianjoining network, phylogenetic trees, AMOVA, haplotype data file, and sites information could provide a wide understanding of the species' relationships. To sum up, integration of IGS1 and ITS regions is recommended for identification of mushroom species in breeding programs including the domestication of native edible fungi, studies on structure mating types, and the production of high yield hybrids.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Research Grants PS291-2009C, PV088-2011B, and 66-02-03-0074 from the Institute of Research Management and Monitoring (IPPP), University of Malaya.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Zeng F, Hon CC, Zhang Y, Leung FCC. The mitochondrial genome of the Basidiomycete fungus Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2008;280(1):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adebayo EA, Oloke JK, Yadav A, Barooah M, Bora TC. Improving yield performance of Pleurotus pulmonarius through hyphal anastomosis fusion of dikaryons. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;29:1029–1037. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adejumo TO, Awosanya OB. Proximate and mineral composition of four edible mushroom species from South Western Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;4(10):1084–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zervakis G, Balis C. A pluralistic approach in the study of Pleurotus species with emphasis on compatibility and physiology of the European morphotaxa. Mycological Research. 1996;100(6):717–731. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravash R, Shiran B, Alavi AA, Bayat F, Rajaee S, Zervakis GI. Genetic variability and molecular phylogeny of Pleurotus eryngii species-complex isolates from Iran, and notes on the systematics of Asiatic populations. Mycological Progress. 2010;9(2):181–194. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi DB, Ding JL, Cha WS. Homology search of genus Pleurotus using an internal transcribed spacer region. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering. 2007;24(3):408–412. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YS, Lee SS. Utilisation of macrofungi species in Malaysia. Fungal Diversity. 2004;15:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urbanelli S, Della Rosa V, Punelli F, et al. DNA-fingerprinting (AFLP and RFLP) for genotypic identification in species of the Pleurotus eryngii complex. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;74(3):592–600. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0684-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma KH, Lee GA, Lee SY, et al. Development and characterization of new microsatellite markers for the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2009;19(9):851–857. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0811.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan PS, Jiang JH. Preliminary research of the RAPD molecular marker-assisted breeding of the edible basidiomycete Stropharia rugoso-annulata . World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2005;21(4):559–563. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez P, Labarère J. Phylogenetic relationships of Pleurotus species according to the sequence and secondary structure of the mitochondrial small-subunit rRNA V4, V6 and V9 domains. Microbiology. 2000;146(1):209–221. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-1-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen HDT, Seifert KA. Description and DNA barcoding of three new species of Leohumicola from South Africa and the United States. Persoonia: Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2008;21:57–69. doi: 10.3767/003158508X361334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seifert KA, Samson RA, DeWaard JR, et al. Prospects for fungus identification using CO1 DNA barcodes, with Penicillium as a test case. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(10):3901–3906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611691104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estrada AER, Jimenez-Gasco MDM, Royse DJ. Pleurotus eryngii species complex: sequence analysis and phylogeny based on partial EF1α and RPB2 genes. Fungal Biology. 2010;114(5-6):421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begerow D, Nilsson H, Unterseher M, Maier W. Current state and perspectives of fungal DNA barcoding and rapid identification procedures. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;87(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2585-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifert KA. Progress towards DNA barcoding of fungi. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(1):83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(16):6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Caldeira K, et al. Limits of nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences as species barcodes for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:10741–10742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207143109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avin FA, Bhassu S, Shin TY, Sabaratnam V. Molecular classification and phylogenetic relationships of selected edible Basidiomycetes species. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39:7355–7364. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoch CL, Seifert KA. Reply to Kiss: internal transcribed spacer (ITS) remains the best candidate as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi despite imperfections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(27, article E1812) doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang JX, Huang CY, Ng TB, Wang HX. Genetic polymorphism of ferula mushroom growing on Ferula sinkiangensis. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;71(3):304–309. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0139-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babasaki K, Neda H, Murata H. megB1, a novel macroevolutionary genomic marker of the fungal phylum basidiomycota. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2007;71(8):1927–1939. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito T, Tanaka N, Shinozawa T. Characterization of subrepeat regions within rDNA intergenic spacers of the edible basidiomycete Lentinula edodes . Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2002;66(10):2125–2133. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupuis JR, Roe AD, Sperling FAH. Multi-locus species delimitation in closely related animals and fungi: one marker is not enough. Molecular Ecology. 2012;21:4422–4436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avin FA, Bhassu S, Sabaratnam V. A simple and low-cost technique of DNA extraction from edible mushrooms examined by molecular phylogenetics. Research on Crops. 2013;14:897–901. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann B, Eckert SE, Krappmann S, Braus GH. Polymorphism at the ribosomal DNA spacers and its relation to breeding structure of the widespread mushroom Schizophyllum commune . Genetics. 2001;157(1):149–161. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zoller S, Lutzoni F, Scheidegger C. Genetic variation within and among populations of the threatened lichen Lobaria pulmonaria in Switzerland and implications for its conservation. Molecular Ecology. 1999;8(12):2049–2059. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardes M, Bruns TD. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—application to the identification of Mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology. 1993;2(2):113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden T. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(article 134) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu K, Kanno M, Yu H, Li Q, Kijima A. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Zhikong scallop Chlamys farreri (Bivalvia: Pectinidae) Molecular Biology Reports. 2011;38(5):3067–3074. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-9974-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1999;16(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbi JC, Vaughan G, Purdy MA, et al. Epidemic history and evolutionary dynamics of Hepatitis B virus infection in two remote communities in rural Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011615.e11615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinteiro J, Rodríguez-Castro J, Rey-Méndez M. Population genetic structure of the stalked barnacle Pollicipes pollicipes (Gmelin, 1789) in the northeastern Atlantic: influence of coastal currents and mesoscale hydrographic structures. Marine Biology. 2007;153(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lechner BE, Petersen R, Rajchenberg M, Albertó E. Presence of Pleurotus ostreatus in Patagonia, Argentina. Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia. 2002;19(2):111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siddiquee S, Tan SG, Yusuf UK, Fatihah NHN, Hasan MM. Characterization of Malaysian Trichoderma isolates using random amplified microsatellites (RAMS) Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(1):715–722. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0790-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ro HS, Kim SS, Ryu JS, Jeon CO, Lee TS, Lee HS. Comparative studies on the diversity of the edible mushroom Pleurotus eryngii: ITS sequence analysis, RAPD fingerprinting, and physiological characteristics. Mycological Research. 2007;111(6):710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi D, Park SS, Ding JL, Cha WS. Effects of Fomitopsis pinicola extracts on antioxidant and antitumor activities. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering. 2007;12(5):516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zervakis GI, Venturella G, Papadopoulou K. Genetic polymorphism and taxonomic infrastructure of the Pleurotus eryngii species-complex as determined by RAPD analysis, isozyme profiles and ecomorphological characters. Microbiology. 2001;147(11):3183–3194. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fries EM. Epicrisis systematis mycologici, seu synopsis hymenomycetum. Typographia Academica; 1838. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singer R. New and interesting species of Basidiomycetes. Mycologia. 1945;37(4):425–439. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pegler DN, Yi-Jian YA. The distinction between Lentinus sajor-caju and Pleurotus ostreatus and their taxonomy. Acta Metallurgica Sinica. 1995;17:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li XL, Yao YJ. Revision of the taxonomic position of the Phoenix Mushroom. Mycotaxon. 2005;91:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shnyreva AA, Sivolapova AB, Shnyreva AV. The commercially cultivated edible oyster mushrooms Pleurotus sajor-caju and P. pulmonarius are two separate species, similar in morphology but reproductively isolated. Russian Journal of Genetics. 2012;48:1080–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zervakis G, Sourdis J, Balis C. Genetic variability and systematics of eleven Pleurotus species based on isozyme analysis. Mycological Research. 1994;98(3):329–341. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iracabal B, Zervakis G, Labarere J. Molecular systematics of the genus Pleurotus: analysis of restriction polymorphisms in ribosomal DNA. Microbiology. 1995;141(6):1479–1490. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer CP, Paulay G. DNA barcoding: error rates based on comprehensive sampling. PLoS Biology. 2005;3(12, article e422) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilmore SR, GrÄfenhan T, Louis-Seize G, Seifert KA. Multiple copies of cytochrome oxidase 1 in species of the fungal genus Fusarium . Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(1):90–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vialle A, Feau N, Allaire M, et al. Evaluation of mitochondrial genes as DNA barcode for Basidiomycota. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(1):99–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]