Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is a leading cause of end stage renal disease among HIV-1 seropositive patients with advanced HIV disease. Renal parenchymal features of HIVAN include focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, podocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation, tubular cell apoptosis, and tubular microcystic dilation [1]. With widespread use of combination anti-retroviral therapy (cART), the impact of HIVAN has been dramatically reduced [2, 3]. In spite of cART, however, some HIV-1 seropositive patients still progress to end stage renal failure. Furthermore, HIVAN remains a major health issue in Africa [4].

HIV-1 expression in the kidney epithelial cells is thought to be responsible for HIVAN pathogenesis [5]. When non-structural components of the HIV-1 genome [6] or the gene encoding for the HIV-1 accessory protein nef [7] were over-expressed in podocytes of transgenic mice, podocytes de-differentiated and acquired a proliferative phenotype. nef activates signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 signaling and drives dedifferentiation and proliferation of cultured podocyte [8]. Consistent with this, STAT3 signaling is activated in podocytes of patients with HIVAN and the Tg26 murine model of HIVAN [8]. We demonstrated previously that Tg26 mice with global reduction of STAT3 activity were protected from the development of HIVAN, which suggests that STAT3 is required for podocyte proliferation [9]. However, since STAT3 expression is ubiquitous and reduction of STAT3 activity in our previous murine model was not cell specific, we could not distinguish the relative importance of STAT3 in different cell types (i.e. kidney vs. infiltrating inflammatory cells) for HIVAN pathogenesis. Here, we specifically examined the role of podocyte STAT3 on the development of HIVAN.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The classic HIV-transgenic mouse model, Tg26, is on the FVB/N background [10]. We generated mice with podocyte-specific deletion of Stat3 on the FVB/N background by backcrossing mice with a floxed Stat3 allele (STAT3f) [11] to FVB/N mice for 6 generations, which was then crossed to a line of FVB/N mice with podocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase [12]. Subsequent F1xF1 breeding of mice heterozygous for the STATf allele and positive for the Cre transgene (Cre+;STAT3f/+) yielded progeny with podocyte-specific deletion of STAT3 (Cre+;STAT3f/f) and control littermates without STAT3 deletion (Cre+;STAT3+/+).

Tg26 mice were bred with Cre+;STAT3f/f mice to generate Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/f mice. Male Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/f mice were crossed to female Cre+;STAT3+/f mice to generate the 4 groups of mice used in the experiments. Eight male mice per group were included. Four mice were killed at 4 and 7 weeks of age. Body weight, urine, and serum were obtained at the termination of the study. Studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines of and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Antibodies

A rabbit antibody against total STAT3 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); a rabbit antibody against Wilm’s Tumor 1 (WT-1) and a monoclonal antibody against nephrin were from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA); a mouse antibody against actin was from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); a FITC-conjugated antibody against mouse CD3e antigen was from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA); a PE-conjugated antibody against mouse F4/80 antigen was from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA); and a rabbit antibody against synaptopodin was a gift from Dr. Peter Mundel (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA).

Primary podocyte culture

Glomeruli were extracted by perfusion of magnetic particles [13]. Extracted glomeruli were cultured on collagen-coated plates for 5 days in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovin serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C. Five days later, cells were detached with 0.12% trypsin-EDTA solution, filtered through a 30μM filter and collected for western blotting.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using 40-to-100μg of denatured protein lysates per lane depending on the protein of interest as described previously [14].

Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and TUNEL staining of kidney tissue

Kidney samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned to 4μm thickness. Periodic Acid Schiff’s stained sections were used for assessment of histologic changes. An examiner masked to the experimental condition quantified the extent of renal pathology using histologic criteria that had been described [9].

Kidney tissues embedded in OCT compound. Frozen sections were used for immunofluorescence staining of WT-1, STAT3, CD3, and F4/80. Results of immunofluorescence staining were imaged at 200x or 400x using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 IE microscope as previously described [15]. The percent area of renal tissue covered by staining was quantified using ImageJ.

DeadEnd Colometric TUNEL System from Promega (Madison, WI) was used to detect apoptotic cells. Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded kidney tissue were processed using manufacturer’s protocol. Sections were incubated with the DAB chromogen for nine minutes. For each mouse, more than 3mm2 of renal tissue per mouse were assessed. Four mice per group were examined. Results are presented as number of TUNEL positive cells per mm2 of renal tissue.

Quantification of serum urea nitrogen and urine albumin and creatinine

Serum urea nitrogen (SUN) and urine creatinine were quantified using commercial kits from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA, USA). Urine albumin was determined using a commercial assay from Bethyl Laboratory Inc. (Houston, TX, USA). Urine albumin excretion was expressed as the ratio of urine albumin to creatinine (UAC).

Coomasie blue staining of urinary proteins

Five μL of urine were denatured with Laemmli sample buffer and then resolved on an 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis. Proteins on the gel were detected by Coomassie blue staining.

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR)

One microgram of total RNA extracted from glomerular extracts were reverse transcribed to complementary DNA, which was used in quantitative RTPCR [14] with the following primer pairs: GCC ATC AAC GAC CCC TTC AT and ATG ATG ACC CGT TTG GCT CC for Gapdh, CAA AGC CAG AGT CCT TCA GAG and GCC ACT CCT TCT GTG ACT CC for interleukin 6 (Il6), CAC AGT TGC CGG CTG GAG CAT and GTA GCA GCA GGT GAG TGG GGC for chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (Ccl2), CCC TCA CAC TCA GAT CAT CTT CT and GCT ACG ACG TGG GCT ACA G for tumor necrosis factor α (Tnfα), TTC TGG GGA GAG GGT GAG TT and GCC ATC CGA CTG CAT CTA TT for chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 2 (Cxcl2), GCC ATC TGG GCC AAA GAT ACC and GTC TTC GCA TGA ATA GGC CAA T for epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr), CCG TGC AGT CGT CCG CTT CCG and GGG TCC GCG GTG CTC CAC CAT for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam1), and GGT CCC TCG CCC AGG TCC TT and GCG TGC TTC GGG GGT CAC TC for suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (Socs3). Gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and fold change in expression relative to the Cre+;STAT3+/+ group (biological control) was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Three technical replicates per gene and 4 biological replicates (mice) per group were used.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. For comparison of means between 3 or more groups, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was applied. For comparisons of means between 2 groups, two-tailed, unpaired t tests were performed. Prism 5 (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Mice with podocyte-specific STAT3 deletion

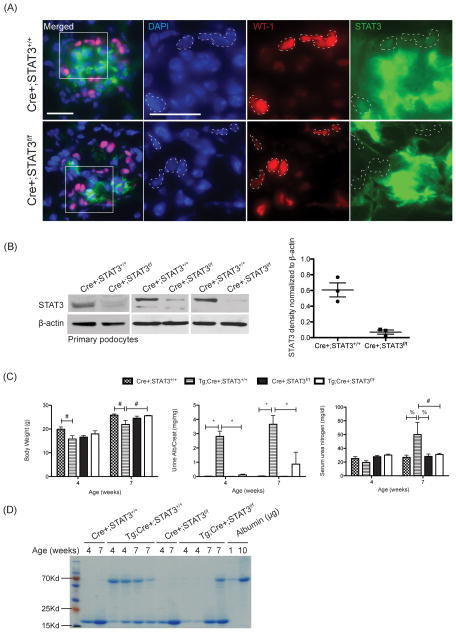

Podocyte-specific deletion of STAT3 was confirmed by co-immunolabeling of STAT3 and a podocyte-specific marker, WT-1. Co-labeling of STAT3 and WT-1 in the Cre+;STAT3f/f kidney was markedly less than the Cre+;STAT3+/+ kidney (Fig 1A). Knockdown of podocyte STAT3 expression was also confirmed by western blotting for STAT3 in isolated primary podocytes (Fig 1B).

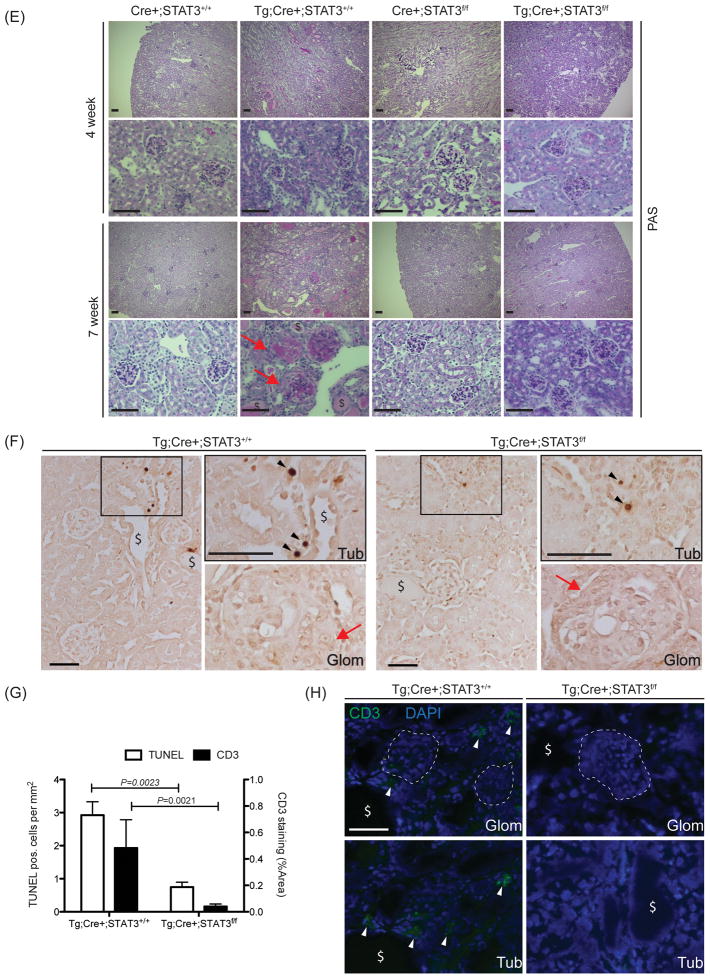

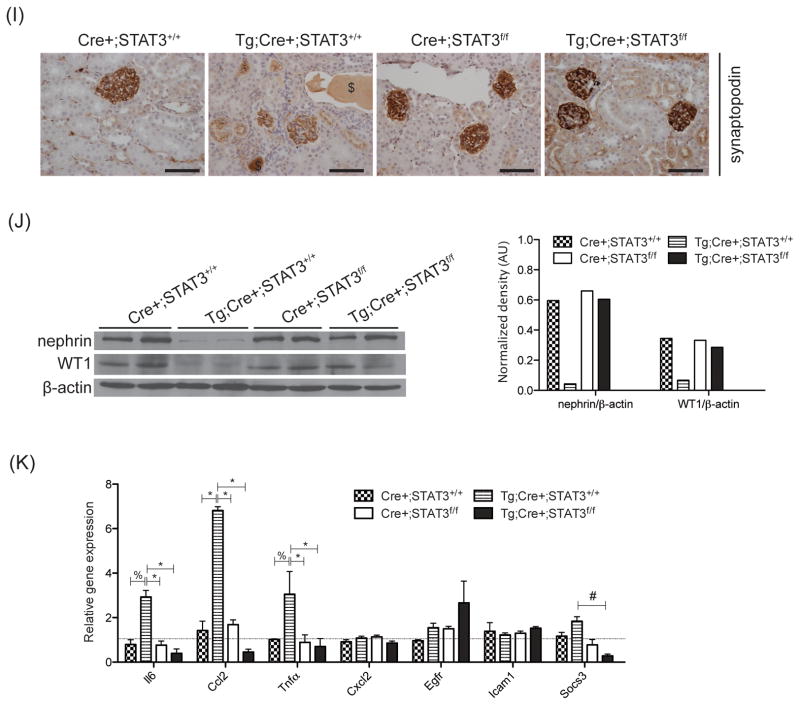

Figure 1. Renal phenotype of Tg26 mice with or without podocyte-specific STAT3 deletion.

(A) STAT3 and Wilms Tumor 1 (WT-1) staining: representative images of STAT3 and WT-1 co-labeling in glomeruli of Cre+;STAT3+/+ and Cre+;STAT3f/f mice. Magnified views of the area circumscribed by the white box in the Merged image are displayed in separate channels corresponding to DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), WT-1, and STAT3. White dashed lines outline the WT-1 positive areas. (B) Podocyte STAT3 western blots: Western blots and a graph of normalized band densitometric values. (C) Body weight, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, and serum urea nitrogen concentration: Values at 4 and 7 weeks of age. n=4 mice/group. (D) Coomasie blue staining of representative urine samples from either 4 or 7 week-old mice. Each lane contains a sample from a different mouse. Albumin protein standards (1 and 10 μg/lane) were added to verify the identity of the 70kD band. (E) Period Acid Schiff staining: representative images of kidney sections of 4 and 7 week-old mice. (F) Representative images of TUNEL staining for 7 week-old mice: Magnified images of the tubular region (Tub) circumscribed by the black-line box contain TUNEL positive cells (black arrowheads). Glomeruli (Glom) with epithelial cell hyperplasia (Red arrows) do not have TUNEL staining. (G) A graph summarizing TUNEL and CD3 staining results for 7 week-old mice. (H) Images of CD3 staining (green; white arrowheads). Tubular (Tub) and glomerular (Glom) areas are shown. (I) Synaptopodin staining in 7 week-old mice. (J) Left panel: Western blots of nephrin, Wilm’s tumor 1 (WT1), and β-actin of total kidney lysates from two 7 week-old mice of each genotype. Right panel: Normalized band densitometric values for the western blots in the left panel. AU: arbitrary unit. (K) Relative expression of STAT3 target genes in glomeruli of 7 week-old mice of different genotypes (n=4 per group). Il6, interleukin 6; Ccl2, chemokine C-C motif ligand 2; Tnfα, tumor necrosis factor α; Cxcl2, C-X-C motif ligand 2; Egfr, epidermal growth factor receptor; Icam1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; Socs3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. %P<0.01, *P<0.001, #P<0.05, Scale bar: 20μm. Red arrows: Glomerular epithelial cell hyperplasia. $: Dilated tubules with and without tubular proteinaceous cast.

Tg26 mice with podocyte STAT3 deletion developed less renal dysfunction

To examine whether podocyte STAT3 deletion is sufficient to prevent the development of HIVAN in Tg26 mice, we compared the body weight (BW), UAC, and SUN levels of Tg26 and non-Tg26 mice, with and without STAT3 deletion. Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice weighed significantly less than Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice at both 4 and 7 weeks of age (Fig 1C, left panel, 15.8±1.4g vs. 19.9±0.97g and 21.9±1.6g vs. 25.8±0.51g, n=4 per group, P<0.05). BW of Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice were not significantly different from Cre+;STAT3+/+, Cre+;STAT3f/f, or Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice at 4 weeks of age, but were significantly higher than Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice at 7 weeks of age (25.6±0.21g vs. 21.9±1.6g, n=4 per group, P<0.05).

Urinary albumin excretion, which is a marker of glomerular injury, was quantified by UAC. UAC of Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice was significantly higher than that of Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice at 4 and 7 weeks of age (Fig 1C, middle panel, 2.81±0.37mg/mg vs. 0.02±0.01mg/mg and 3.66±0.61mg/mg vs. 0.03±0.02mg/mg, n=4 per group, P<0.001). UAC of Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice was significantly lower than that of Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice at both 4 and 7 weeks of age (0.113±0.05mg/mg vs. 2.81±0.37mg/mg and 0.87±0.84mg/mg vs. 3.66±0.61mg/mg, n=4 per group, P<0.001), but was not significantly different from Cre+;STAT3+/+ and Cre+;STAT3f/f mice. Coomasie blue staining of urinary proteins revealed that proteins in the urine were predominately albumin (Fig 1D). Freely filtered proteins (<20kD) were observed in all urine samples, but consistently higher in 7-week-old mice for all groups. Urinary albumin for one of the two 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice was more than the other 7-week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice and was also more than both of the 7-week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice (Fig 1D). This urine sample was collected from one of the four 7-week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice that had more severe pathologic features of HIVAN (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of kidney histology

| Group (sample size n=4at 4W and 7W of age) | Glomerular Compartment | Tubulo-Interstitial Compartment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerular Collapse & Sclerosis (30 glomeruli) | Glomerular epithelial cell hyperplasia (0–3+) | Tubular Degenerative/R egenerative Changes (0–3+) | Cortex with Casts/Cysts (%) | Tubular Atrophy/Interstitial Fibrosis (%) | ||||||

| 4W | 7W | 4W | 7W | 4W | 7W | 4W | 7W | 4W | 7W | |

| # Cre+;STAT3+/+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ | 0 | 14/30 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 20 | 0 | 20 |

| 4/30 | 6/30 | 1+ | 2+ | 0 | 1+ | 10 | 20 | 5 | 5 | |

| 2/30 | 15/30 | 0 | 3+ | 0 | 1+ | 5 | 30 | 0 | 20 | |

| 1/30 | 14/30 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 1+ | 5 | 15 | 5 | 10 | |

| # Cre+;STAT3f/f | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 2/30 | 0 | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 10 | |

No glomerular or tubulo-interstitial lesions were observed in any of the mice in these groups.

The level of SUN, which is inversely related to renal function, at 7 weeks of age was significantly higher in Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice compared to Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f (Fig 1C, right panel, 60.0±17.8mg/dl vs. 31.1±1.7mg/dl, #P<0.05, n=4 per group), Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice (60.0±17.8mg/dl vs. 26.9±3.4mg/dl, %P<0.01, n=4 per group), and Cre+;STATf/f mice (60.0±17.8mg/dl vs. 28.2±3.4mg/dl, %P<0.01, n=4 per group). No significant difference in serum urea nitrogen was observed between the four groups at 4 weeks of age.

Renal pathology of Tg26 mice with and without STAT3 deletion

Kidney sections of 4 and 7 week-old mice were scored for glomerular and tubulointerstitial (T-I) features. Glomerular and T-I features of HIVAN were more severe in 7 week-old vs. 4 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice (Table 1, representative pictures in Fig 1E). Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice had less glomeruli with collapse/sclerosis and a lower degree of glomerular epithelial hyperplasia compared to 4 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice. In fact, glomerular and T-I features were absent in all 4 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice. In two of the 7-week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice, no glomerular or T-I HIVAN findings were observed. Although some glomerular and T-I pathologic features were observed in the other two 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice, they were markedly less than 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice.

In HIVAN, apoptosis is observed in tubular cells, but not glomerular cells [16]. To determine where podocyte STAT3 deletion had any impact on tubular cell apoptosis in HIVAN kidneys, we performed TUNEL labeling (Fig 1F). TUNEL staining was not observed in glomerular cells and in kidneys of non-Tg26 mice. The number of TUNEL positive cells per mm2 of renal tissue was significantly higher in 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice compared to Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice (2.9±0.4 vs. 0.75±0.1 TUNEL positive cells per mm2 renal tissue, n=4 per group, P=0.0023, Fig 1G).

To determine the effect of podocyte STAT3 deletion on mononuclear cell infiltration in HIVAN kidneys, we performed CD3 and F4/80 immunostaining for lymphocytes and macrophages, respectively (Fig 1F, G, and H). The percent area of renal tissue with CD3 staining was significantly less in 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice compared to Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice (0.55±0.10 vs. 0.04±0.02 % area, n=4 per group, P=0.0021, Fig 1G). F4/80 staining was not significantly different between 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ and Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice (0.180±0.10 vs. 0.16±0.93 % area, n=4 per group, P>0.05).

Expression of podocyte differentiation markers and STAT3 target genes

Synaptopodin, a marker of podocyte differentiation, was markedly reduced in 7 week-old Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ kidney compared to other groups (Fig 1I). Expression of other podocyte differentiation markers (i.e. nephrin and WT-1) were also reduced in the Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ kidneys, but preserved in Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f kidneys, when compared to non-Tg26 kidneys (Fig 1J).

The glomerular expressions of STAT3 target genes involved in inflammatory response—Il6, Ccl2, and Tnfα—were significantly higher in Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice compared to all other groups (Fig 1K). Socs3 expression was significantly lower in Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f compared to Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice. The glomerular expressions of other STAT3 target genes—Cxcl2, Egfr, and Icam1—were not significantly different between the groups.

Discussion

Since STAT3 deletion was restricted to the podocytes of Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice, we had anticipated those mice to develop less severe glomerular injury, but we had not expected them to be protected from tubular injury. Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice developed less glomerular collapse, sclerosis, epithelial cell hyperplasia, and podocyte dedifferentiation; and they also had less tubular atrophy, degeneration, apoptosis, and lymphocyte infiltration compared to Tg;Cre+;STAT3+/+ mice. Since the only difference between these two groups of mice is STAT3 expression in the podocytes, we concluded that manifestation of tubular pathology in Tg26 mice is dependent on the expression of podocyte STAT3.

Our findings are in line with the idea that glomerular injury precedes and likely predisposes to subsequent inflammation and apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells in HIVAN [16–19]. Consistent with our findings, transgenic mice with podocyte-specific expression of nonstructural HIV genes developed glomerular and podocyte abnormalities prior to the onset of tubular changes [6]. Although HIV-induced dysregulation of cytokinesis and apoptosis [19] as well as the expression of ubiquitin-like protein FAT10 [18] and pro-inflammatory mediators [17] have been reported in tubular epithelial cells, in light of our results, those mechanisms are more likely to be ancillary factors rather than direct initiators of tubular injury in HIVAN.

Cre-mediated deletion of STAT3 driven by the 2.5kb human podocin promoter in the podocyte was incomplete based on our immunostaining and western blot results. This podocin-Cre line is widely used and incomplete Cre-mediated recombination in the podocytes has been reported [20, 21]. Despite incomplete STAT3 silencing, Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice were still protected from HIVAN, which suggests that podocyte STAT3 is an important driver in the pathogenesis of HIVAN. However, since STAT3 deletion was incomplete and Tg;Cre+;STAT3f/f mice were partially protected from HIVAN, it is not possible to determine whether the lack of complete protection was due to either incomplete STAT3 deletion or additional STAT3-independent pathogenic mechanisms. We suspect the answer is probably the latter as we and others have identified several other molecular mediators that also contribute to the pathogenesis of HIVAN (i.e. HIPK2 [15], MAPK1,2 [8], TGF-β [22, 23], sidekick-1 [24], VEGF [25]). However, the relationship of STAT3 with other pathogenic factors remains to be elucidated

cART is the standard of care for treatment of HIVAN and the diagnosis of HIVAN is an indication for initiation of cART [26, 27]. However, some patients with HIVAN still progress despite being on cART. Our study suggests that reduction of STAT3 activation could be a potential adjunctive therapeutic strategy for those patients. Direct STAT3 inhibitors [28] and kinase inhibitors of Janus kinases (JAK) [29, 30], which are upstream non-receptor tyrosine kinases that activate STAT3 signaling, have been studied in non-renal diseases and could be used to inhibit STAT3 activity. Since the JAK-STAT pathway is also a critical signaling pathway in diabetic nephropathy [31], we believe that our study could have a broader implication for other forms of kidney diseases that involve activation of JAK/STAT signaling. Future studies are needed to establish whether podocyte STAT3 plays a role in the development of diabetic nephropathy.

We conclude that podocyte STAT3 is required for the full manifestation of the HIVAN phenotype. These results further clarified the pathogenesis of HIVAN and could have an impact on the selection of therapeutic agents for the treatment of HIVAN and non-HIVAN kidney diseases.

Acknowledgments

JCH is supported by NIH 1R01DK078897 and 1R01DK088541-01A1 and a Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 1I01BX000345; PYC is supported by NIH 5K08DK082760. L.G., Y.D., and J.X. performed the experiments. L.G. and P.Y.C. analyzed the data. J.H. and P.Y.C. designed the experiments and authored the manuscript. S.M., L.K., and P.E.K. contributed to study design and discussion.

Footnotes

Statement of competing financial interests

The authors have no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Peter Y. Chuang, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1243, New York NY 10029

Leyi Gu, Renal Division and Molecular Cell Laboratory for Kidney Disease, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Yan Dai, Div of Nephrology, Shanghai First People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Jin Xu, Div. of Nephrology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Sandeep Mallipattu, Div. of Nephrology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Lewis Kaufman, Div. of Nephrology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Paul E. Klotman, Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas, USA.

John Cijiang He, Div. of Nephrology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA. Renal Section, James J Peter Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, New York, USA.

References

- 1.D’Agati V, Appel GB. HIV infection and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:138–152. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V81138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt CM, Klotman PE, D’Agati VD. HIV-associated nephropathy: clinical presentation, pathology, and epidemiology in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters PJ, Moore DM, Mermin J, Brooks JT, Downing R, Were W, et al. Antiretroviral therapy improves renal function among HIV-infected Ugandans. Kidney Int. 2008;74:925–929. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyatt CM, Meliambro K, Klotman PE. Recent progress in HIV-associated nephropathy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:147–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041610-134224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leventhal JS, Ross MJ. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong J, Zuo Y, Ma J, Fogo AB, Jolicoeur P, Ichikawa I, et al. Expression of HIV-1 genes in podocytes alone can lead to the full spectrum of HIV-1-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1048–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain M, D’Agati VD, He JC, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. HIV-1 Nef induces dedifferentiation of podocytes in vivo: a characteristic feature of HIVAN. AIDS. 2005;19:1975–1980. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191918.42110.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He JC, Husain M, Sunamoto M, D’Agati VD, Klotman ME, Iyengar R, et al. Nef stimulates proliferation of glomerular podocytes through activation of Src-dependent Stat3 and MAPK1,2 pathways. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:643–651. doi: 10.1172/JCI21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng X, Lu TC, Chuang PY, Fang W, Ratnam K, Xiong H, et al. Reduction of Stat3 activity attenuates HIV-induced kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2138–2146. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopp JB, Klotman ME, Adler SH, Bruggeman LA, Dickie P, Marinos NJ, et al. Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1577–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby JJ, Kalinowski A, Liu MG, Zhang SS, Gao Q, Chai GX, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of STAT3 results in higher sensitivity to inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and heart failure with advanced age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12929–12934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134694100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moeller MJ, Sanden SK, Soofi A, Wiggins RC, Holzman LB. Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2003;35:39–42. doi: 10.1002/gene.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takemoto M, Asker N, Gerhardt H, Lundkvist A, Johansson BR, Saito Y, et al. A new method for large scale isolation of kidney glomeruli from mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:799–805. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang PY, Dai Y, Liu R, He H, Kretzler M, Jim B, et al. Alteration of forkhead box O (foxo4) acetylation mediates apoptosis of podocytes in diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Y, Ratnam K, Chuang PY, Fan Y, Zhong Y, Dai Y, et al. A systems approach identifies HIPK2 as a key regulator of kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2012;18:580–588. doi: 10.1038/nm.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodi I, Abraham AA, Kimmel PL. Apoptosis in human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:286–291. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross MJ, Fan C, Ross MD, Chu TH, Shi Y, Kaufman L, et al. HIV-1 infection initiates an inflammatory cascade in human renal tubular epithelial cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:1–11. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000218353.60099.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder A, Alsauskas Z, Gong P, Rosenstiel PE, Klotman ME, Klotman PE, et al. FAT10: a novel mediator of Vpr-induced apoptosis in human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. J Virol. 2009;83:11983–11988. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00034-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenstiel PE, Gruosso T, Letourneau AM, Chan JJ, LeBlanc A, Husain M, et al. HIV-1 Vpr inhibits cytokinesis in human proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1049–1058. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding M, Coward RJ, Jeansson M, Kim W, Quaggin SE. Regulation of Hypoxia -nducible Factor 2-Alpha is Essential for Integrity of the Glomerular Barrier. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00416.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godel M, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Liu S, Zschiedrich S, Lu S, et al. Role of mTOR in podocyte function and diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2197–2209. doi: 10.1172/JCI44774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto T, Noble NA, Miller DE, Gold LI, Hishida A, Nagase M, et al. Increased levels of transforming growth factor-beta in HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1999;55:579–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodi I, Kimmel PL, Abraham AA, Svetkey LP, Klotman PE, Kopp JB. Renal TGF-beta in HIV-associated kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1568–1577. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman L, Hayashi K, Ross MJ, Ross MD, Klotman PE. Sidekick-1 is upregulated in glomeruli in HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1721–1730. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128975.28958.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korgaonkar SN, Feng X, Ross MD, Lu TC, D’Agati V, Iyengar R, et al. HIV-1 upregulates VEGF in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:877–883. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, Boydstun, Ahuja TS, Rodriguez RA, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1559–1585. doi: 10.1086/430257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adolescents. PoAGfAa. Dep Health Hum Serv. 2011. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected adults and adolescents; pp. 1–167. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page BD, Ball DP, Gunning PT. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 inhibitors: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2011;21:65–83. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.539205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sansone P, Bromberg J. Targeting the interleukin-6/Jak/stat pathway in human malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1005–1014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Shea JJ, Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity. 2012;36:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthier CC, Zhang H, Schin M, Henger A, Nelson RG, Yee B, et al. Enhanced expression of Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway members in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2009;58:469–477. doi: 10.2337/db08-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]