Summary

The receptor tyrosine kinase AXL regulates melanoma cell proliferation and migration. We now demonstrate that AXL and the related kinase MERTK are alternately expressed in melanoma and are associated with different transcriptional signatures. MERTK-positive melanoma cells are more proliferative and less migratory than AXL-positive melanoma cells and overexpression of AXL increases cell motility relative to MERTK. MERTK is expressed in up to 50% of melanoma cells and shRNA-mediated knockdown of MERTK reduces colony formation and cell migration in a CDC42-dependent fashion. Targeting MERTK also decreases cell survival and proliferation in an AKT-dependent manner. Finally, we identify a novel mutation in the kinase domain of MERTK, MERTKP802S, that increases the motility of melanoma cells relative to wild-type MERTK. Together, these data demonstrate that MERTK is a possible therapeutic target in melanoma, that AXL and MERTK are associated with differential cell behaviors, and that mutations in MERTK may contribute to melanoma pathogenesis.

Keywords: AXL, MERTK, melanoma, migration, survival

Introduction

Patients with metastatic melanoma have a median survival rate of 6–10 months and a 5-yr survival rate of 5–10% (Leung et al., 2012; Siegel et al., 2012). There is consequently a great need to develop improved therapeutics for the treatment of melanoma. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) regulate a plethora of cell behaviors associated with cancer progression including survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Our previous work showed that RTKs including MET, RON, HER3, AXL, and IGF1R are active in melanoma, but to date only a few RTKs have been studied in the context of melanoma biology (Tworkoski et al., 2011).

The TAM family of RTKs includes three members: TYRO3 (also called DTK or RSE), AXL (also called UFO or TYRO7), and MERTK (also called c-RYK, c-EYK, or c-MER). The role of TAMs in normal physiology and disease states has been extensively reviewed (Linger et al., 2008). TAMs functionally engage in cooperative or distinct signaling depending on the model system. Auto-immune and reproductive disorders are more pronounced in double or triple TAM knockout mice compared to single knockout mice, suggesting cooperative signaling (Lu and Lemke, 2001; Lu et al., 1999). In contrast, phagocytosis is regulated by distinct TAMs in different cell types (Seitz et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2008). Despite evidence that TAMs play a key role in cancer pathogenesis, few studies have directly compared the role of TAM receptors to determine the functional overlap of these RTKs.

Overexpression of AXL transforms murine fibroblasts and AXL expression is elevated in prostate, bladder, breast, and ovarian cancer as well as leukemia, astrocytoma, and oral squamous cell carcinoma (Keating et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; O’Bryan et al., 1991; Paccez et al., 2012; Rankin et al., 2010; Sayan et al., 2012; Vuoriluoto et al., 2011). In cancerous tissue, AXL is generally associated with increased cellular survival, proliferation, invasion, migration, and poor prognosis (Lee et al., 2011; Paccez et al., 2012; Sayan et al., 2012). In agreement with these data, we and others have reported increased AXL expression in a subset of melanoma cell lines and tumors relative to melanocytes and have shown that targeting AXL reduces melanoma cell proliferation and migration (Sensi et al., 2011; Tworkoski et al., 2011). Similarly, targeting TYRO3 reduces melanoma cell proliferation and tumor formation while enhancing chemosensitivity (Zhu et al., 2009).

MERTK is largely known for its role in mediating phagocytosis and cytoskeletal rearrangements (Guttridge et al., 2002; Qingxian et al., 2010; Seitz et al., 2007). Mutations, deletions, and alternative splicing thought to decrease MERTK expression or activation have been linked to defective phagocytosis in the uveal membrane, resulting in a disease known as retinitis pigmentosa (Gal et al., 2000; Siemiatkowska et al., 2011). Fibroblasts can be transformed by a chimeric MERTK receptor and MERTK expression is elevated in leukemia, glioblastoma, NSCLC, astrocytoma, and prostate cancer (Keating et al., 2010; Ling and Kung, 1995; Linger et al., 2009; Riess and Neal, 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2004). In cancer, MERTK expression is associated with cell survival, resistance to chemotherapy, and cytokine secretion while accelerating tumor development in murine model systems (Linger et al., 2009; Riess and Neal, 2011; Wu et al., 2004). MERTK mutations are rarely found in tumors and the functional relevance of identified mutations has not been explored in the context of melanoma biology (Greenman et al., 2007; Hucthagowder et al., 2012).

To date, there is little evidence linking MERTK to melanoma pathogenesis. A bioinformatic screen suggests that MERTK may be differentially regulated in melanoma, but mechanistic details and physiological relevance were not elucidated (Gyorffy and Lage, 2007). Our previous analysis demonstrated that MERTK is expressed and may be activated in melanoma cell lines, but we did not investigate how MERTK influences melanoma development (Tworkoski et al., 2011). Here, we demonstrate that MERTK is activated in melanoma and that MERTK signaling regulates multiple aspects of melanoma biology. We further show that TAM family members AXL and MERTK correlate with distinct melanoma cell phenotypes. We also report a novel mutation in the MERTK kinase domain and characterize the effects of this mutant on melanoma cell behavior. Together, these data offer new insight into the role of TAM family members in cancer and identify MERTK as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of melanoma.

Results

MERTK and AXL are differentially expressed in melanoma

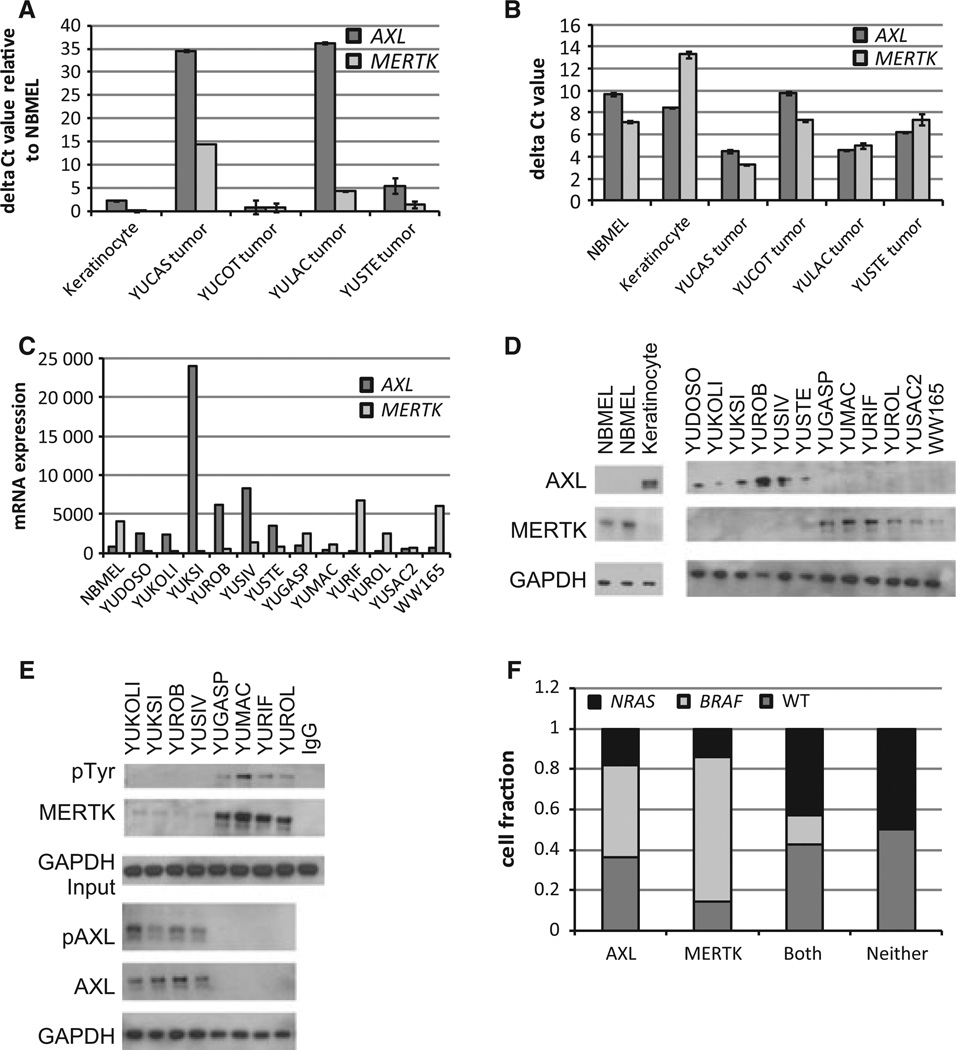

Analysis of tumor cores from the Human Protein Atlas database revealed that AXL and MERTK are expressed in melanoma tumors (Table S1) (Uhlen et al., 2010). We used qRT-PCR to verify that AXL and MERTK had elevated expression in melanoma tumors relative to normal newborn melanocytes (NBMELs) (Figure 1A). Interestingly, NMBELs, keratinocytes, and 3 of 4 melanoma tumors had at least a twofold difference in relative expression of AXL and MERTK (Figure 1B). Examination of melanoma cell lines revealed that most cells predominantly express either AXL or MERTK at the mRNA and protein level (Figure 1C, D). Immunoblotting also confirmed that keratinocytes predominantly express AXL, while NBMELs express MERTK (Figure 1D). Immunoblot analysis of 36 melanoma cell lines demonstrated that 69% (25/36) of cells express either AXL or MERTK individually, while 19% (7/36) express both RTKs simultaneously and 11% (4/36) express neither RTK (Figure 1D; Figure S1A; data not shown). AXL protein was expressed without MERTK in 31% (11/36) of cell lines, while MERTK was expressed without AXL in 39% (14/36) of cell cultures (Figures 1D and S1A; data not shown). AXL and MERTK are also differentially activated in melanoma lines (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

AXL and MERTK are alternately expressed in melanoma. (A, B) Relative expression of AXL and MERTK mRNA in melanoma tumors, keratinocytes, and NBMELs determined via qRT-PCR. Results were normalized either to internal GAPDH controls (B; delta Ct values—lower bars indicate higher expression) and to GAPDH internal controls taken relative to NBMELs, which express endogenous MERTK but not AXL (A; delta delta Ct values—higher bars indicate higher expression). AXL data in (A, B) were published previously (Tworkoski et al., 2011). (C) Expression of AXL and MERTK mRNA as determined by NimbleGen microarray. Results are expressed in arbitrary units. (D) Lysates from melanoma cell lines and NBMELs were immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (E) Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with MERTK and immunoblotted with either anti-MERTK or anti-pTyr. In parallel, whole cell lysates were probed with anti-GAPDH. Additional samples were probed with anti-AXL, anti-pAXL, and anti-GAPDH. (F) 36 melanoma cell lines were immunoblotted to assess expression of AXL and MERTK. AXL-positive cell lines were 36% (4/11) WT, 45% (5/11) BRAF mutant and 18% (2/11) NRAS mutant. MERTK-positive cell lines were 14% (2/14) WT, 71% (10/14) BRAF mutant, and 14% (2/14) NRAS mutant. Cell lines with both RTKs were 43% (3/7) WT, 14% (1/7) BRAF mutant, and 43% (3/7) NRAS mutant. Cell lines with neither RTK were 50% WT (2/4) and 50% (2/4) NRAS mutant.

Melanomas are characterized by activating mutations in NRAS or BRAF, which are predominantly mutually exclusive and constitutively activate the MAPK signaling pathway. NRAS mutations occur in 15–20% of melanoma patients, while BRAF mutations occur in ~45% of melanoma patients (Scolyer et al., 2011). We examined 36 melanoma cell lines including 11 wild-type (WT) for NRAS and BRAF, 16 BRAF mutant lines, and 9 NRAS mutant lines for AXL and MERTK expression. AXL-positive cell lines did not segregate with a given mutational subtype (Figures 1F and S1B). In contrast, 71% of MERTK-expressing cell lines (10/14) harbored BRAF-activating mutations and 63% (10/16) of the BRAF mutant cell lines examined expressed MERTK alone (Figures 1F and S1B).

AXL and MERTK correlate with different gene signatures and cellular behavior in melanoma

We next sought to determine if AXL or MERTK expression was associated with specific transcriptional signatures. The relationship between expression of AXL or MERTK and all other genes was evaluated across 40 melanoma cell lines using non-parametric statistical analysis of NimbleGen expression data. Expression of MERTK correlated positively with genes such as NRG3, TYR, MLANA, and CDH1, while AXL mRNA was positively associated with ADAM19, WNT5A, and VEGFC (Table S2). Interestingly, AXL and MERTK correlated inversely with many of the same genes including kinases (MET, FYN, NLK), transcription factors (MITF, SOX10, GATA6, E2F8), signal transducers (SMAD3, SHC4, RND3), ubiquitin ligases (SMURF2, MUL1, UBE2M), and regulators of cell adhesion (MMP3, CDH2, CYR61, CTGF) (Tables S2 and S3). Furthermore, many cell lines expressing both AXL and MERTK displayed intermediate gene expression patterns relative to cells with only AXL or MERTK expression. For example, WNT5A was most highly expressed in AXL-positive cell lines, intermediately expressed in AXL-and MERTK-positive cells, and expressed at low levels in MERTK-positive cells (Table S4). Analysis of 4 melanoma cell lines for CDH1, CDH2, WNT5A, MITF, and TYR expression validated the results of the correlation studies (Figure S1C). These associations were not necessarily dependent on AXL or MERTK, because knockdown or overexpression of AXL or MERTK did not reproducibly alter mRNA expression of CDH1, CDH2, WNT5A, MITF, or MLANA (data not shown).

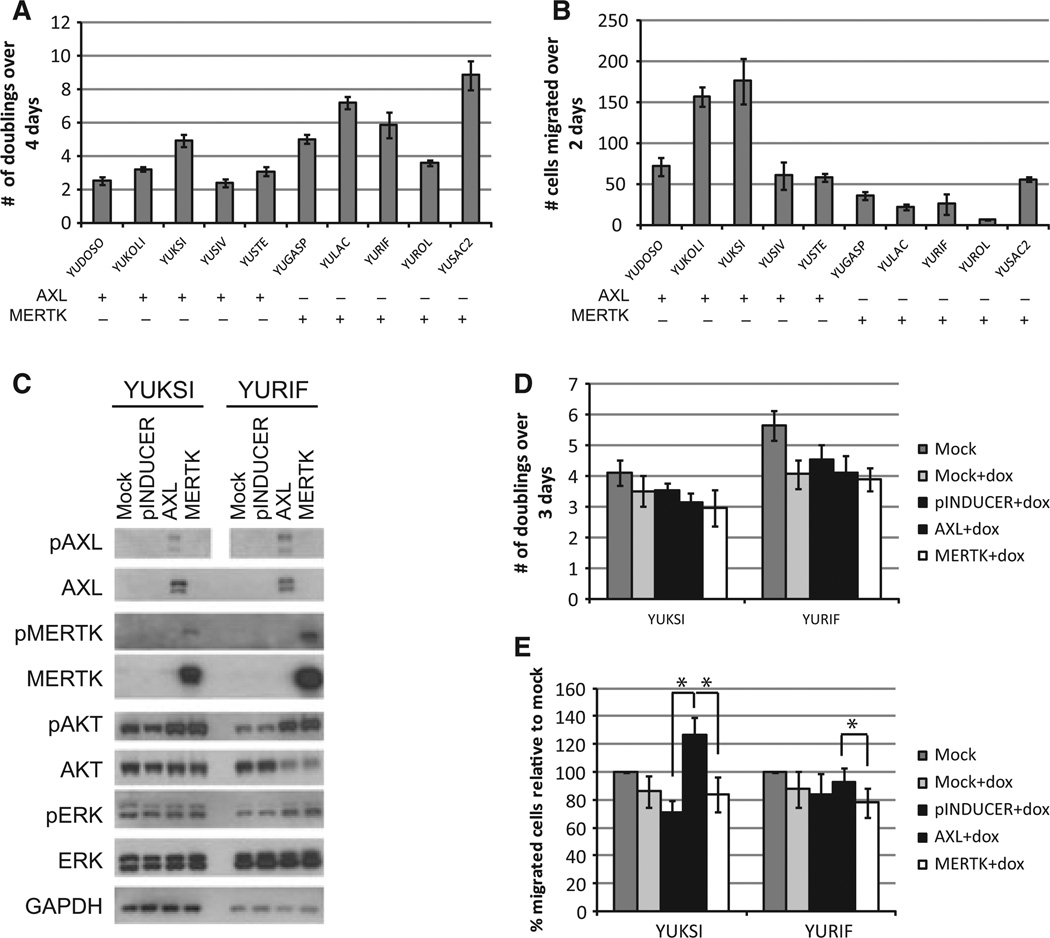

We then used the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) to determine whether AXL and MERTK could be linked to different signaling pathways (Huang da et al., 2009a,b). AXL was repeatedly associated with pathways regulating blood vessel development and cell motility, while MERTK was associated with guanyl nucleotide binding and mitochondrial signaling (Tables S5 and S6). To determine whether AXL or MERTK correlated with different phenotypes, we compared the proliferation and migration of AXL-positive and MERTK-positive cell lines. Cell lines expressing AXL were significantly more migratory and less proliferative than cell lines expressing MERTK (P < 0.01) (Figure 2A, B). To ascertain whether AXL or MERTK is sufficient to alter cell behavior, we expressed AXL and MERTK cDNAs under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter in cells with endogenous AXL (YUKSI) or MERTK (YURIF) (Figure 2C). Doxycycline treatment induced exogenous AXL or MERTK cDNA to such an extent that endogenous levels of the respective receptors were not detectable in the same immunoblot exposures (Figure 2C). Induced overexpression of AXL and MERTK stimulated phosphorylation of both receptors and resulted in activation of the AKT signaling pathway, although neither receptor significantly altered cellular proliferation (Figure 2C, D). Elevated expression of AXL significantly increased cell motility relative to MERTK in YUKSI and YURIF cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 2E). AXL also significantly elevated cell motility relative to empty backbone controls in YUKSI, although not in YURIF cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

AXL and MERTK expression correlate with cell motility and proliferation. (A, B) The proliferation (A) and migration (B) of five AXL-positive cell lines and five MERTK-positive cell lines were assessed using the CellTiter-Glo and transwell assays, respectively. Collectively, AXL-positive cells proliferate more and migrate less than MERTK-positive cells (P < 0.01). (C) An AXL-positive cell line (YUKSI) and a MERTK-positive cell line (YURIF) were infected with lentivirus containing AXL cDNA, MERTK cDNA, or an empty backbone control (pINDUCER) under the regulation of a doxycyline-inducible promoter. Expression of the indicated proteins was examined after 24 h treatment with 100 ng/ml doxycycline. pAXL was assessed in parallel immunoblots. (D, E) Cell lines infected with the indicated vector were treated with doxycycline. Proliferation was measured using CellTiter-Glo (D) and migration was measured in a transwell system (E). *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Targeting MERTK reduces cellular proliferation, migration, and AKT signaling

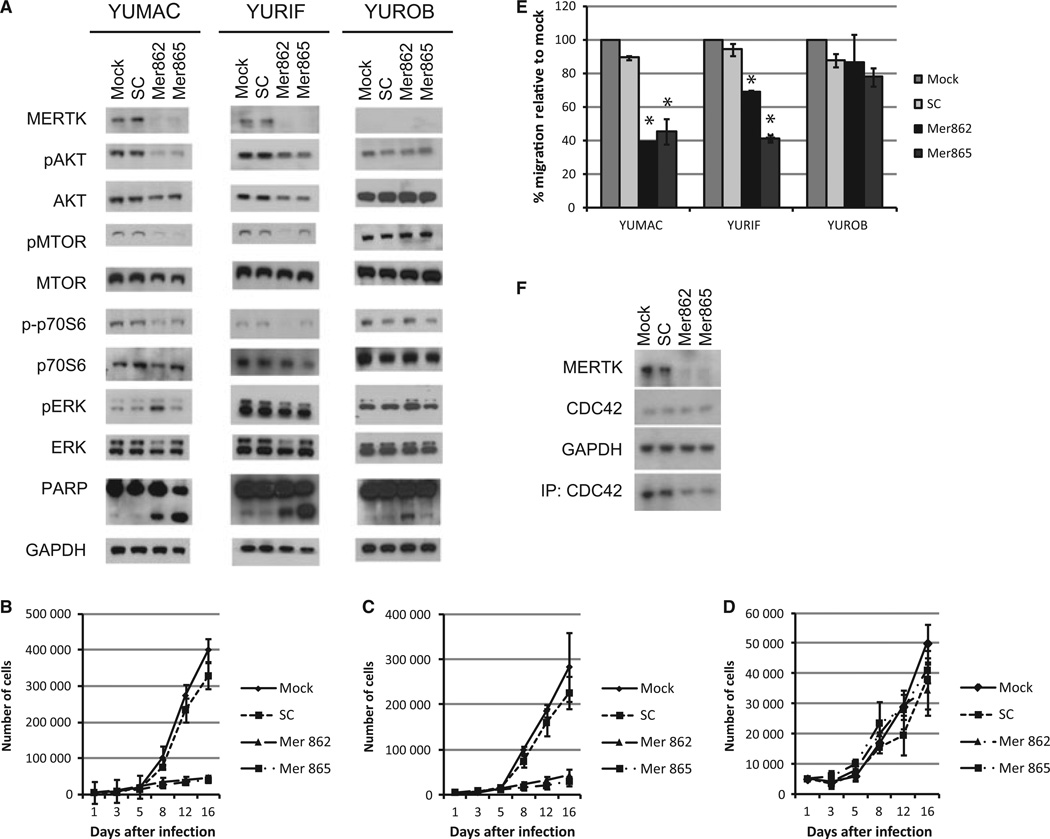

Interrogation of the Oncomine database revealed that MERTK expression generally increased over the course of melanoma development (Figure S2A) (Rhodes et al., 2004). Specifically, MERTK was elevated in melanoma compared to nevi in 3/3 studies and MERTK expression was increased in metastatic melanoma relative to primary melanoma in 3/4 studies. To explore whether MERTK affects melanoma cell phenotype, we evaluated the impact of two MERTK-directed shRNAs on two BRAF mutant MERTK-positive cell lines (YURIF and YUMAC) and a BRAF WT MERTK-negative melanoma cell line (YUROB) (Figure 3A). In MERTK-positive lines, suppression of MERTK-reduced AKT activation, signaling through downstream effectors MTOR and p70S6 kinase, and activation of general AKT substrates, but did not alter ERK activation (Figures 3A and S2B). Neither YUMAC nor YURIF express AXL, and knockdown of MERTK did generate a compensatory increase in AXL expression (Figure S2C). Targeting MERTK did not alter signaling in the MERTK-negative YUROB cell line (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

MERTK knockdown reduces cell proliferation, AKT signaling, and migration. (A) Cells were treated with mock infection, lentivirus encoding scrambled (SC) shRNA, or 2 different MERTK shRNAs (Mer862 and Mer865). Expression of MERTK and activation of downstream signaling pathways was assessed 5 days after knockdown. (B–D) Cell lines were infected with MERTK shRNA or controls and seeded at equal density 24 h later. Cells were trypsinized and counted over a 16-day period. Two MERTK-positive cell lines, YUMAC (B) and YURIF (C) were analyzed along with YUROB, a MERTK-negative cell line (D). (E) Cells were infected with MERTK shRNA and migration through a transwell system was assessed. (F) Five days after infection, the activity of CDC42 was assessed via immunoprecipitation with the PBD of PAK1. In parallel, lysates were probed for the proteins indicated. *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05) relative to SC control.

Suppression of MERTK over a 16-day period caused a dramatic reduction in cell proliferation relative to controls (Figures 3B–D and S2C). Targeting MERTK did not alter cell proliferation for the first 3 days after knockdown (Figure 3B–D). We therefore assessed cell migration during this initial 3-day period to prevent differential growth rates from affecting our analysis. Knockdown of MERTK significantly reduced cell migration in MERTK-positive YUMAC and YURIF melanoma cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 3E). It is known that MERTK can influence cell motility by regulating the RhoA family via VAV1 (Mahajan and Earp, 2003). To determine if MERTK modulates the RhoA family, we used the p21 binding domain (PBD) of p21 activated protein kinase (PAK) to pull down active RAC1 and CDC42. Although sporadic fluctuations in RAC1 activity were observed, consistent reductions in CDC42 activity were noted upon MERTK knockdown (Figure 3F, data not shown). Suppression of MERTK did not alter the proliferation or migration of MERTK-negative YUROB cells, indicating that our observations are not due to off-target effects of the shRNAs (Figure 3D–E).

Given the association between MERTK expression and BRAF mutation, we wondered if MERTK is a possible therapeutic target in cells without BRAF mutations. MERTK knockdown reduced AKT signaling, cell proliferation, and cell migration in the NRAS mutant MERTK-positive YUGASP cell line (Figure S2D–F). The data were comparable to results observed with BRAF mutant cell lines, indicating that targeting MERTK is effective independent of BRAF mutation status.

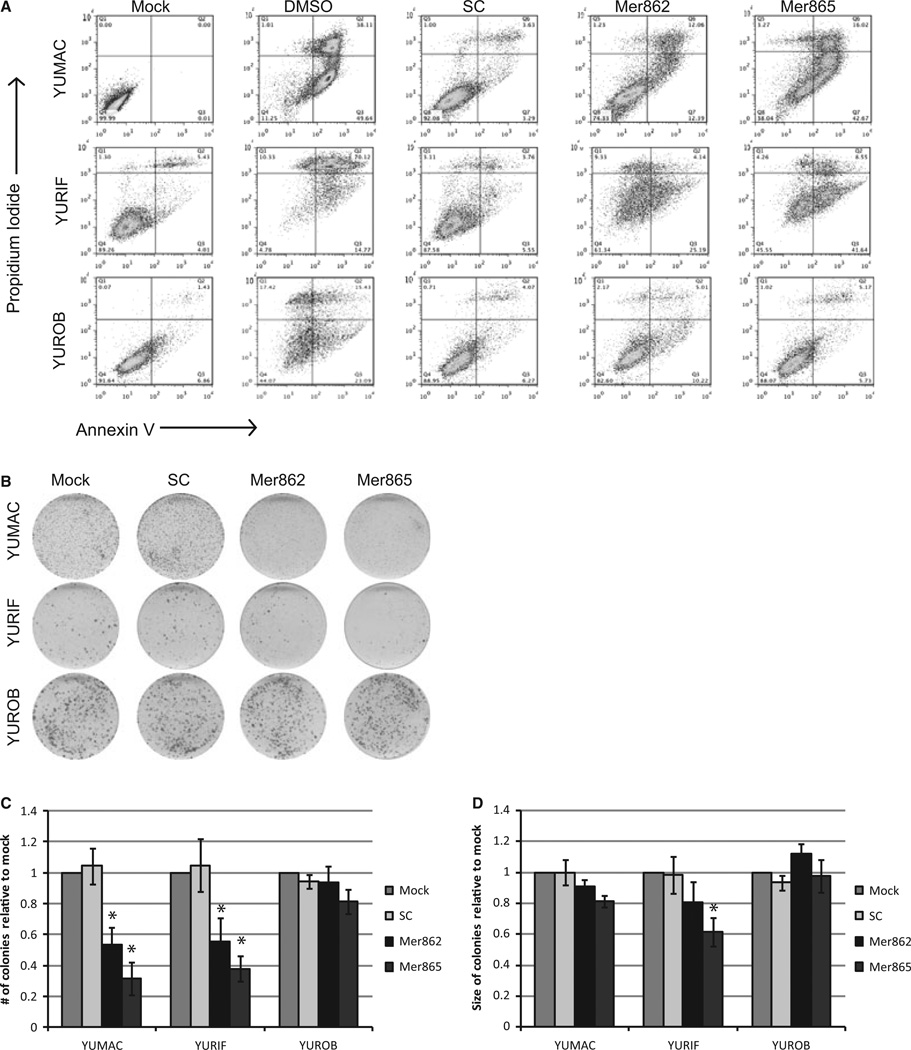

Suppression of MERTK expression reduces colony formation and cell survival

Targeting MERTK reduced the net growth of melanoma cells and simultaneously increased cleaved PARP (Figures 3A–C and S2D, E). Although occasional PARP cleavage was observed in YUROB cells, these changes were not reproducible and did not always coincide with the presence of MERTK shRNA (Figure 3A). We used flow analysis to quantify staining for annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) as a measure of apoptosis. High concentrations of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used to kill cells as a positive control. Five days after MERTK knockdown, the number of YUMAC and YURIF cells in the early (Annexin V positive) or late (PI positive, Annexin V positive) stages of apoptosis increased dramatically (Figure 4A; Table S7). Similarly, MERTK knockdown significantly decreased the number of colonies YUMAC and YURIF cells formed in a clonogenic assay (P < 0.05) (Figure 4B, C). Colony size was also decreased in these cells, although the difference was generally not significant (P < 0.05) (Figure 4B–D). MERTK shRNA did not greatly affect the survival or colony-forming capabilities of the YUROB cell line, which verifies that the observed effects are due to manipulation of MERTK expression (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

MERTK knockdown reduces cell survival and clonogenic colony formation. (A) Cells were treated with MERTK shRNA or with the indicated controls. Five days after infection, flow analysis was performed to assess the percentage of cells positive for Annexin V and Propidium Iodide. The quadrants are quantified in Table S7. (B–D) Cells were seeded at equal density 1 day after the indicated treatment and colonies were stained 10 days later (B). Relative colony number (C) and size (D) were assessed using ImageJ. *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05) relative to SC control.

Cells with stable MERTK knockdown regain AKT-dependent proliferation and survival but not migration

Although transient MERTK knockdown decreased AKT signaling and proliferation in YUMAC and YURIF cells, these effects were not sustained after 4–6 weeks of puromycin selection (Figure S3A, B). Interestingly, both transient and stable knockdown of MERTK significantly reduced the migration of YUMAC and YURIF cells (P < 0.05) (Figure S3C). Analysis of YUMAC cells verified that decreased cell motility correlated with reductions in active CDC42 under stable knockdown conditions (Figure S3D). Unlike transiently infected cells, stable suppression of MERTK in YUMAC and YURIF cells did not cause an increase in cleaved PARP or alter the levels of apoptotic cells relative to controls (Figure S3A, E; Table S7). Neither transient nor stable knockdown of MERTK greatly altered ERK signaling, and the MERTK-negative YUROB cell line was not affected by the presence of MERTK shRNA regardless of the duration of the infection (Figure S3; Table S7).

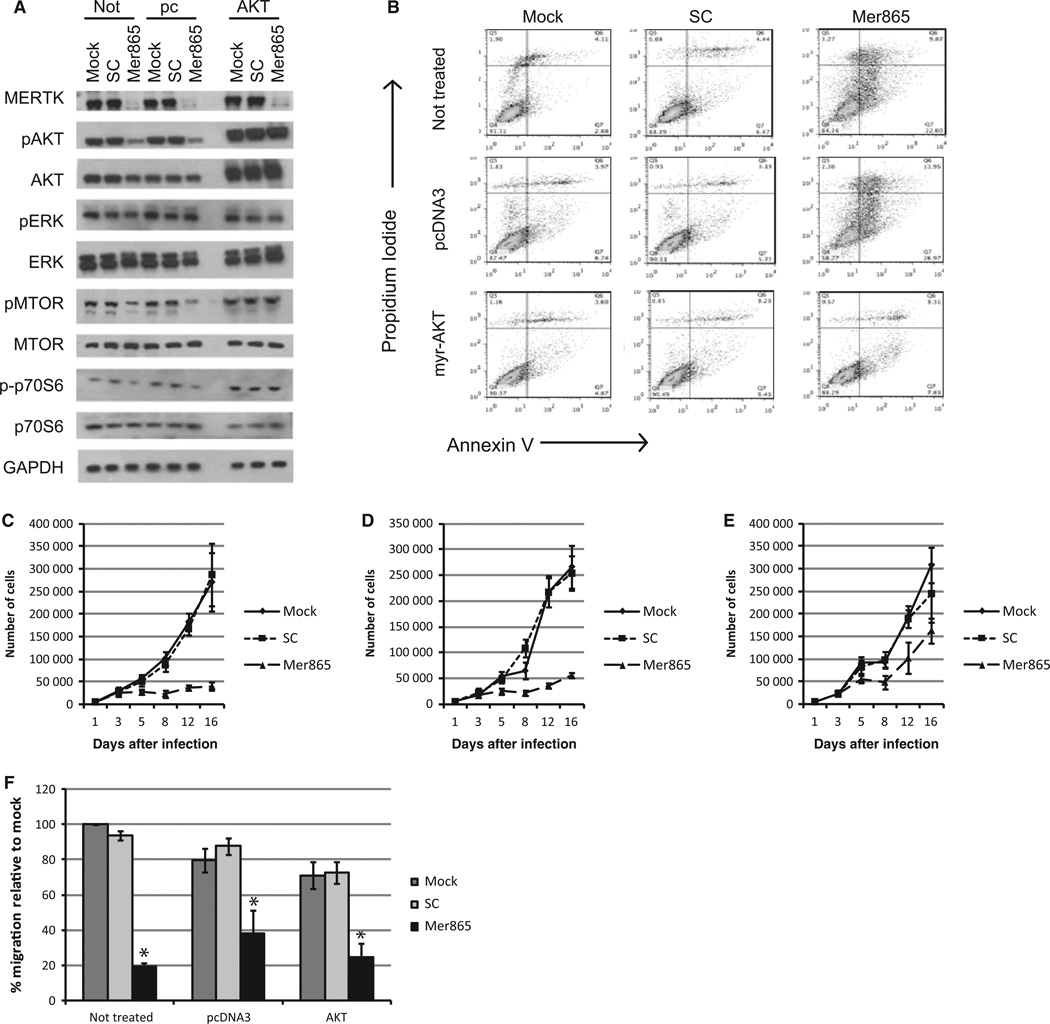

These results suggest that AKT signaling regulates the alterations in cell proliferation and survival observed initially upon MERTK knockdown, while cell motility is regulated by CDC42 in an AKT-independent manner. To explore this hypothesis, we stably transfected myristoylated (myr) AKT cDNA into YUMAC cells. The presence of a myr sequence targets AKT to the membrane, where it can act as a constitutively active kinase (Kohn et al., 1996). As expected, cells with myr-AKT show high constitutive levels of pAKT (Figure 5A). Although high pMTOR was not routinely observed with myr-AKT expression, myr-AKT stabilized pMTOR and p70S6 signaling upon MERTK knockdown while increasing overall p70S6 kinase activity, indicating that the myr-AKT construct effectively activates AKT signaling (Figure 5A). The presence of myr-AKT rescued cell survival as measured by flow microfluorimetry and partially rescued cell proliferation upon MERTK knockdown (Figure 5B–E; Table S7). As expected, myr-AKT does not alter cell migration (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

AKT signaling rescues melanoma cell proliferation and survival. YUMAC melanoma cells were stably transfected with myr-AKT (AKT), pcDNA3 empty backbone (pc), or were not transfected (Not). They were then mock infected or were incubated with lentivirus containing SC shRNA or Mer865 shRNA. (A) Protein expression was assessed 5 days after knockdown. (B) Five days after lentiviral infection, flow analysis was used to assess the amount of cells that were positive for annexin V and propidium iodide staining. Number of cells in each quadrant is listed in Table S7. (C–E) Cell proliferation of non-transfected (C), pcDNA3-transfected (D), or myr-AKT transfected (E) cells was assessed after the indicated infection. Cells were counted over a 16-day period. (F) Cell migration was determined via transwell assay. *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05) relative to mock control.

MERTKP802S has reduced Tyr phosphorylation and AKT signaling relative to MERTKWT

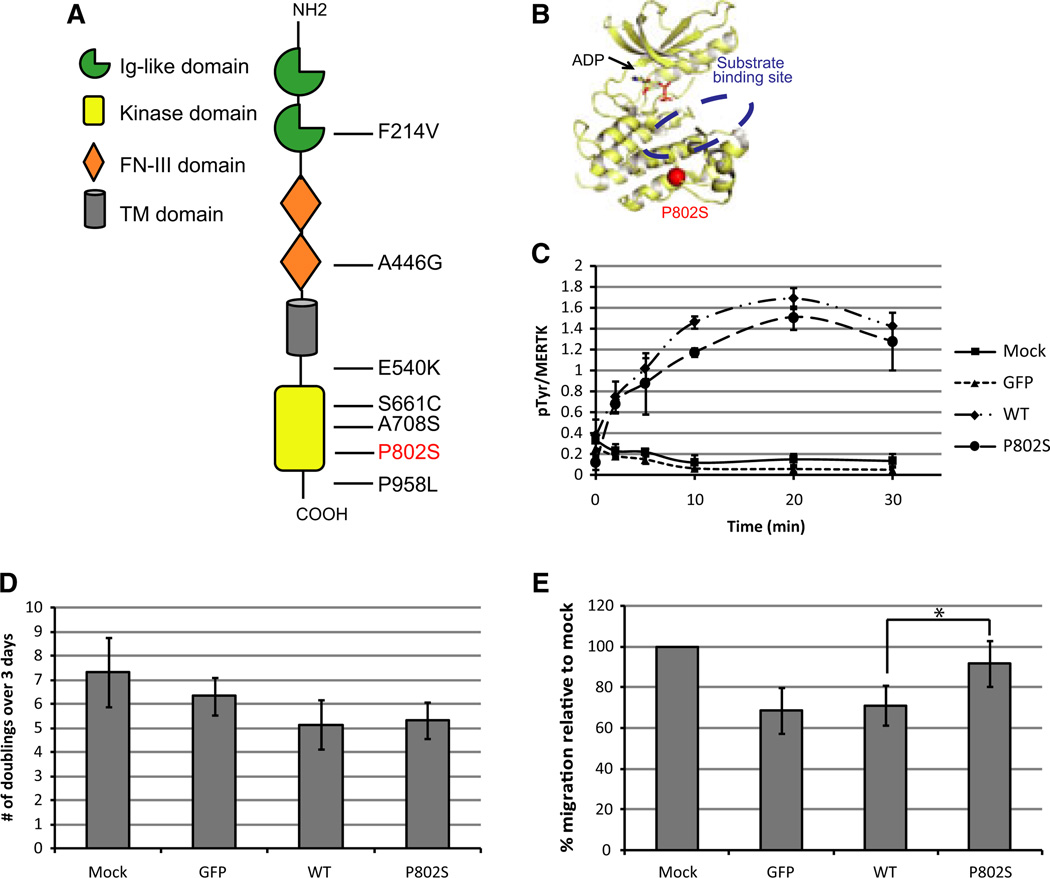

Alterations in MERTK protein and DNA have been described in several diseases. The substitutions F214V and P958L are associated with retinal dystrophy, while E540K and S661C are linked to retinitis pigmentosa (Li et al., 2011). A few somatic MERTK mutations have been observed in cancer, resulting in protein sequence changes A446G in renal cancer and A708S in head and neck carcinoma, but it is not clear if these alterations affect cancer development (Figure 6A) (Greenman et al., 2007). Exome sequencing of the YUHEF melanoma cell line and corresponding tumor tissue revealed a transition C to T mutation at base 2526 in the MERTK NM_006343.2 sequence, resulting in an amino acid switch from P to S at position 802; this mutation is not detected in non-tumor DNA from the same patient and to date, it has only been identified in one melanoma tumor (Figure 6A). MERTKP802S is located in the MERTK kinase domain at the edge of the peptide binding site, where the substitution could potentially affect substrate binding or specificity (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

MERTKP802S is differentially phosphorylated and promotes 293T cell migration. (A) Diagram showing previously identified MERTK mutations and the MERTKP802S mutation (red). (B) Mapping of the MERTKP802S mutation onto the crystal structure of the MERTK kinase domain (PDB ID: 3BRB) (Huang et al., 2009). Kinase domain shown in cartoon format, ADP shown in stick format and the location of P802S mutation is marked as a red sphere. The approximate location of the substrate binding site is indicated for clarity. (C) HEK 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and immune complex kinase assays were performed on the resulting lysates to assess the ratio of pTyr/MERTK after incubation with ATP for the designated time. Ratios of pTyr to MERTK were obtained using ImageJ. (D, E) 293T cells were transfected with the indicated construct. One day after transfection, cells were seeded at equal density and cell proliferation was measured using CellTiter-Glo (D). Cell migration was measured using a transwell system (E). *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05).

To determine if MERTKP802S affects MERTK kinase activity, we expressed MERTKWT and MERTKP802S in 293T cells using GFP as a control (Figure S4A, B). Immune complex kinase assays were performed by incubating MERTK immunoprecipitates with ATP over a 30-min period and assessing the ratio of total pTyr to MERTK over time (Figures 6C and S4C). There was no consistent difference in the initial autophosphorylation rate of MERTKWT and MERTKP802S. Within 10 min, however, the ratio of pTyr/MERTK was slightly higher in MERTKWT than in MERTKP802S, consistent with a small decrement in stability of the MERTKP802S catalytic domain, differential affinity for binding partners, altered specificity for specific autophosphorylation sites, and/or altered phosphatase activity (Figure 6C).

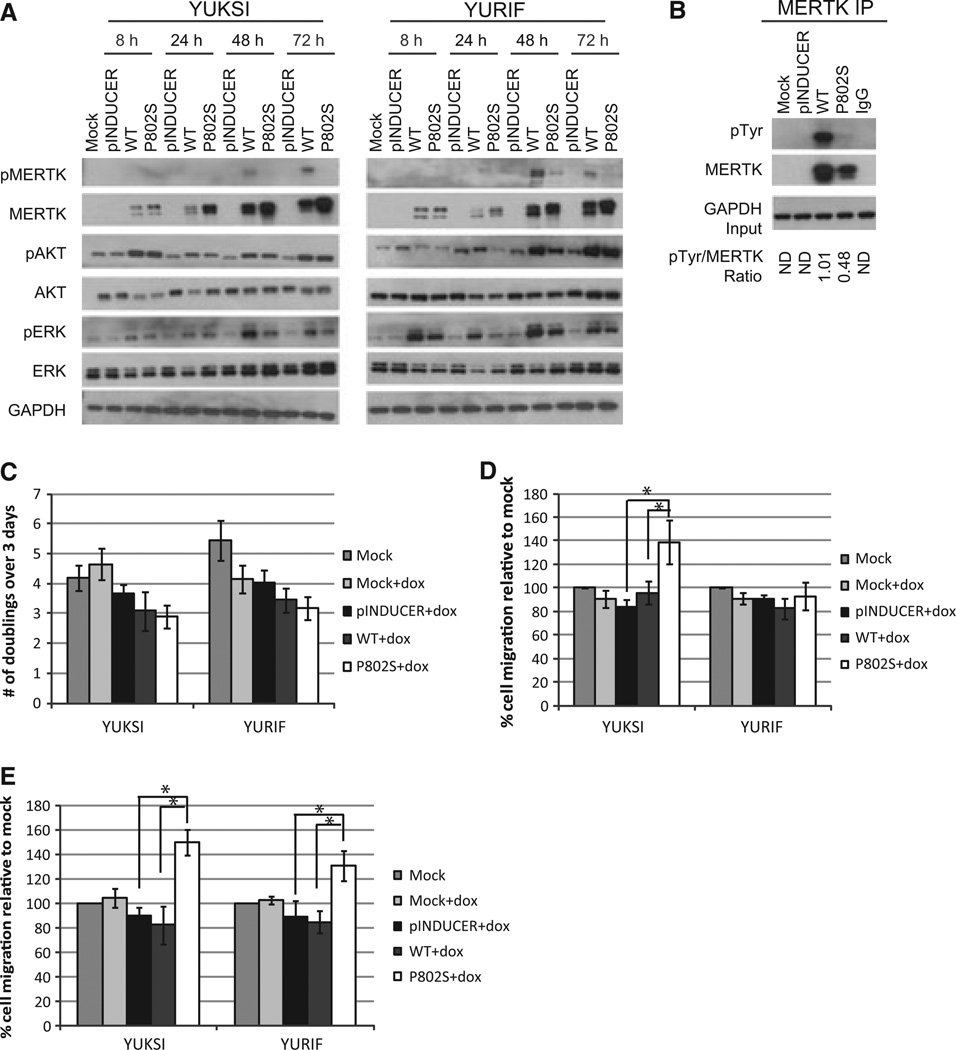

We next examined in vivo phosphorylation of MERTK at Tyr749/753/754, the three main sites of autophosphorylation in the MERTK kinase domain (Ling et al., 1996). YURIF cells express WT MERTK and were used to reconstruct the MERTKP802S heterozygosity in the original YUHEF cells and tumor. YUKSI cells do not express MERTK and were used to compare MERTKWT and MERTKP802S without endogenous MERTK. Melanoma cells were infected with MERTKWT or MERTKP802S under the control of a doxycycline–inducible promoter. Consistent with in vitro kinase assays in 293T cells, phosphorylation of MERTK at Tyr749/753/754 was elevated in MERTKWT compared to MERTKP802S (Figure 7A). As Tyr749/753/754 represent a subset of the Tyr phosphorylation sites in MERTK, we also measured total pTyr in immunoprecipitated MERTK. Total Tyr phosphorylation of MERTKWT was roughly double that of MERTKP802S (Figure 7B). Immunoprecipitation experiments further verified that MERTKP802S and MERTKWT were activated within 24 h of induction (Figure 7B). Thus, our inability to detect pMERTK in total cell lysates within 8–24 h of induction is likely due to limited expression or antibody sensitivity (Figure 7A). Within 1 day of induction, MERTKWT generally increased AKT signaling to a greater extent than MERTKP802S, perhaps reflecting the higher levels pMERTK seen in MERTKWT relative to MERTKP802S (Figure 7A). We also observed elevated ERK signaling after 2–3 days of MERTKWT or MERTKP802S expression, suggesting potential crosstalk between the AKT and ERK signaling pathways over a protracted period of time (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

MERTKP802S differentially regulates AKT signaling and melanoma cell motility. (A) YUKSI and YURIF melanoma cells were infected with the indicated viruses and expression was induced using 100 ng/ml doxycycline for the given time period. Protein expression was assessed via immunoblotting. (B) YUKSI cells were infected with the indicated constructs and lysed after 1 day of doxycycline treatment. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-MERTK and probed for MERTK or pTyr. The ratio of pTyr/MERTK was measured using ImageJ. ND, not determined. (C–E) The indicated constructs were expressed in YUKSI and YURIF cells. Proliferation was measured using CellTiter-Glo (C) and migration was measured via a transwell system for 24 h (D) or 48 h (E). *Values are significantly different (P < 0.05).

MERTKP802S regulates cell motility but not cell proliferation

To explore the physiological role of MERTKP802S, we overexpressed MERTKWT and MERTKP802S in 293T cells and melanoma cells. Examination of 293T and melanoma cells revealed that neither MERTKP802S nor MERTKWT significantly altered proliferation relative to controls (P < 0.05) (Figures 6D and 7C). In contrast, MERTKP802S significantly (P < 0.05) increased cell motility over a 24-h period relative to MERTKWT in 293T and YUKSI cells (Figures 6E and 7D). The same trend was evident in YURIF cell lines, but was not significant (Figure 7D). We posited that the enhanced migratory capacity of YUKSI and 293T cells makes differences easier to detect in these cell lines. In agreement with this notion, analysis of cell migration over a 48-h period revealed that MERTKP802S significantly increases cell motility relative to MERTKWT and controls in both YUKSI and YURIF cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 7E).

Discussion

Emerging evidence suggests that the TAM family contributes to melanoma pathogenesis. TYRO3 promotes melanoma cell proliferation, colony formation, and in vivo tumorigenesis, while targeting AXL reduces melanoma cell proliferation, migration, and STAT3 signaling (Tworkoski et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2009). We now report that MERTK mRNA is expressed in melanoma tumors and cell lines and that MERTK is functionally active in melanoma cells (Figure 1A–E; Table S1). MERTK is expressed in 58% of cell lines we examined and is generally associated with BRAF-activating mutations; 71% (10/14) MERTK-positive cell lines had BRAF mutations and 63% of BRAF mutant lines (10/16) expressed MERTK (Figures 1F and S1B).

AXL and MERTK expression are mutually exclusive in 69%(25/36) of our melanoma cell lines and AXL correlated with elevated cell motility, while MERTK was associated with increased cellular proliferation (Figures 1C–E and 2A, B, data not shown). These data suggest that AXL and MERTK may be differentially linked to established proliferative and invasive gene signatures in melanoma (Hoek et al., 2008). In support of this notion, AXL correlated positively with multiple genes associated with melanoma invasion, including CDH2 and WNT5A (Table S2) (Qi et al., 2005; Weeraratna et al., 2002). Further, overexpression of AXL increased the migratory capacity of melanoma cells relative to MERTK (Figure 2E). In contrast, MERTK correlates with proliferation markers such as MYC and CDK2, although overexpression of MERTK was not sufficient to alter melanoma cell proliferation (Figure 2D; Table S2) (Mannava et al., 2008). These data suggest that AXL is capable of directly regulating the migratory capacity of melanoma cells, while the correlation between MERTK and cell proliferation may be dependent on other factors.

Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery analysis was used to determine which signaling pathways might be affected by AXL or MERTK expression. Although these results are not definitive, we found that AXL was associated with angiogenic pathways, possibly driven by the positive correlation between AXL and genes such as VEGFC, ANGPT1, and PDGFA (Tables S2, S3 and S5). These data are in agreement with studies suggesting that AXL regulates endothelial tube formation, and imply that AXL may play a role in angiogenesis or vascular mimicry in melanoma (Holland et al., 2005). The associations between MERTK and signaling pathways were not as significant as the AXL associations, but MERTK was linked to several mitochondrial pathways, perhaps driven by positive correlations with BCKDHA and ACO2, and to cell adhesion pathways, possibly driven by associations with MET, FYN, and CDH1 (Tables S2, S3 and S6).

Our correlation analyses also linked MERTK to markers of melanocyte differentiation including MLANA, MITF, and TYR (Tables S2 and S3). Given these associations, it is possible that MERTK is associated with melanocyte development, which would explain why melanocytes endogenously express MERTK. In our hands, manipulation of AXL and MERTK expression does not alter the expression of correlated genes MITF, CDH1, CDH2, WNT5A, or MLANA (Tables S2 and S3; data not shown). We did, however, select arbitrary genes and timepoints for analysis, which may impede our ability to detect causal relationships. It is also possible that these genes are merely correlated with each other or that they are regulated by another, as yet unidentified factor. For instance, MITF is a master regulator of melanocyte gene transcription and is inversely associated with AXL and MERTK—AXL and MERTK may be differential down-stream targets of MITF (Tables S2 and S3) (Sensi et al., 2011). Although we were not able to demonstrate causal relationships, several of the genes correlated with AXL and MERTK have been associated with clinical outcome. Analysis of circulating melanoma cells indicates that MITF and TYR can predict overall patient survival and VEFGC expression has been correlated with melanoma stage and metastasis (Goydos and Gorski, 2003; Samija et al., 2010). It will be useful to see if AXL and MERTK may serve as independent prognostic factors in melanoma.

Tyr 867 on MERTK associates with Grb2 to promote activation of PI3K and AKT signaling (Georgescu et al., 1999). In agreement with these data, targeting MERTK in BRAF mutant (YUMAC and YURIF) and in NRAS mutant (YUGASP) cell lines reduces cell proliferation, phosphorylation of AKT substrates, and activation of AKT itself (Figures 3A–C, S2B and S2D, E). Loss of MERTK expression does not generate a compensatory increase in AXL expression (Figure S2C, D). MERTK knockdown also decreases cell migration (Figures 3E and S2F). Weposited that MERTK might regulate cell motility through activation of RhoA proteins, because phosphorylation of MERTK enables activation of the RhoA family via VAV1 (Mahajan and Earp, 2003). In agreement with this notion, suppression of MERTK reduced the activity of CDC42 in the YUMAC cell line (Figures 3F and S3D). Although MERTK is predominantly expressed in BRAF mutant cell lines, the effects of MERTK knockdown are similar in BRAF and NRAS mutant cells, implying that the efficacy of targeting MERTK does not vary with BRAF mutation status.

Analysis of BRAF mutant cell lines (YUMAC and YURIF) demonstrated that MERTK knockdown decreases the number and size of colonies formed in a clonogenic assay (Figure 4B–D). Furthermore, the decrease in cell proliferation observed over a 16-day period after MERTK knockdown coincides with an increase in cell death, suggesting that MERTK predominantly regulates cell survival (Figures 3A–C and 4A; Table S7). Importantly, shRNA against MERTK does not alter the signaling or behavior of the MERTK-negative YUROB cell line, thereby confirming the specificity of our results (Figures 3 and 4).

Six weeks after MERTK knockdown, cell survival, proliferation, and AKT signaling return to baseline (Figure S3; Table S7). It is probable that the non-apoptotic melanoma cells initially observed upon MERTK suppression grew out over this 6 week time span, suggesting that melanoma cells either intrinsically possess or quickly develop alternate survival mechanisms in the presence of MERTK knockdown (Figure 4A). Intrinsically, resistant cells might possess kinases that compensate for MERTK signaling or mutations or altered expression of genes such as PTEN that allow them to maintain AKT signaling even in the absence of MERTK. Importantly, targeting MERTK reduces melanoma migration and CDC42 activation regardless of the temporal length of the knockdown (Figures 3E, F and S3C, D). Thus, our data suggest that MERTK may control metastasis and that MERTK inhibitors should be combined with antiproliferative agents to generate maximum therapeutic effectiveness.

The correlation between melanoma cell proliferation, survival, and AKT signaling suggested that AKT signaling is responsible for these cellular behaviors (Figures 3A–D and 4A and S3; Table S7). Indeed, the addition of myr-AKT increased cell proliferation and survival upon MERTK knockdown (Figure 5A–E; Table S7). As expected, myr-AKT did not alter cell migration after loss of MERTK expression, indicating that CDC42-regulated cell motility is not dependent on AKT signaling (Figure 5F). Interestingly, knockdown of MERTK does not alter ERK signaling, while overexpression of MERTK increases ERK signaling (Figures 3A and 7A). As most melanomas harbor potent activating mutations in the RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway, it is likely that loss of MERTK by itself does not reduce ERK phosphorylation. In contrast, overexpression of MERTK may provide additional stimuli to increase ERK signaling either directly or via pathway crosstalk.

We report a novel MERTK mutation, MERTKP802S, which was identified in a single melanoma tumor and corresponding cell line. MERTKP802S does not appear to have differential kinase activity relative to MERTKWT (Figure 6C). MERTKP802S does, however, display reduced phosphorylation at Tyr749/753/754 as well as decreased overall levels of pTyr relative to MERTKWT (Figure 7A, B). Immunoprecipitation experiments verified that MERTKWT consistently had 2–3-fold higher levels of pTyr/MERTK relative to MERTKP802S and MERTKWT also elevated AKT signaling relative to MERTKP802S (Figure 7A, B). The RTK FGFR1 has five Tyr sites that are phosphorylated in a specific order and control interactions with downstream substrates (Furdui et al., 2006). Similarly, MERTKP802S may decrease pTyr levels by altering sequential Tyr phosphorylation; this might explain why MERTKP802S autophosphorylation is initially similar to MERTKWT but eventually plateaus below MERTKWT pTyr levels (Figure 6C). MERTKP802S may also modify interactions with downstream targets or phosphatases.

MERTKP802S does not routinely alter cell proliferation, but it does increase cell migration (Figures 6D, E and 7C–E). Indeed, MERTKP802S impacts cell migration over a 24–48 h period, indicating that the observed effects are not transient and may increase further over time (Figure 7D–E). In agreement with our previous results, MERTKP802S-induced migration is not linked to AKT signaling (Figure 7A, D). Interestingly, the YUHEF cell line and tumor in which MERTKP802S was identified has an activating RAC1P29S mutation (Krauthammer et al., 2012). Yet in our hands, MERTK regulates cell motility via CDC42 and MERTKP802S enhances cell migration in cell lines with (YURIF) and without (YUKSI) a RAC1P29S mutation (Figures 3F and 7D, E) (Krauthammer et al., 2012). Collectively, these data suggest that the MERTKP802S mutation may regulate metastatic potential in a clinical setting.

The prevalence of MERTK in melanoma cell lines, combined with the expression of MERTK in melanoma tumors, suggests that MERTK may be an excellent target for selective therapy. Reducing MERTK expression in melanoma cell lines transiently reduces cell proliferation and increases apoptosis while stably decreasing the migratory potential of cancer cells. The fact that MERTK can be effectively targeted in BRAF and NRAS mutant melanomas offers possible clinical applications while suggesting that MERTK-directed therapeutics might be used in combination with genotype-specific therapies such as vemurafenib. We further show that the MERTKP802S mutation can influence cell signaling and migration. Our data indicate that AXL and MERTK are associated with different gene signatures in melanoma. While independently targeting AXL or MERTK reduces melanoma cell migration, AXL is correlated with increased cell migration and AXL expression is sufficient to increase cell motility relative to MERTK. Although MERTK is correlated with increased cell proliferation, overexpression of MERTK is not sufficient to alter cell growth. Together, our data support the notion that the TAM family plays an important role in melanoma pathogenesis and suggests that targeting MERTK may provide novel, efficacious ways to treat melanoma.

Methods

Cell culture, lysis, immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation

Low-passage melanoma cell cultures and melanocytes were obtained from the Tissue Resource Core of the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer and all cell lines were used at or under passage 25 as has been described (Tworkoski et al., 2011). Melanoma cells were maintained in OptiMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. 293T cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% HEPES. Cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 1 and 2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) added immediately before use). Where indicated, 1 mg of protein from cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with a 1:250 dilution of anti-MERTK (mouse). Keratinocyte protein and mRNA were a generous gift from Dr. Keith Choate, Yale University. Antibodies used include anti-MERTK (mouse and rabbit), anti-pMTOR, anti-MTOR, anti-pAKT, anti-AKT, anti-ERK, anti-pERK, anti-PARP, anti-p70S6, anti-p-p70S6, anti-AXL, anti-pTyr (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), anti-GAPDH, anti-CDC42 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and anti-pMERTK (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Activity of CDC42 was assessed using the RAC1/CDC42 Activation Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Briefly, 300 µg of protein lysate was immunoprecipitated with 5 µl of PAK-1 PBD agrose beads and the presence of active CDC42 was assessed with anti-CDC42.

qRT-PCR, NimbleGen microarray, exome sequencing, and structural analysis

NimbleGen microarrays were used to assess relative mRNA expression in melanoma cell lines and data were obtained from the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer as described (Tworkoski et al., 2011). Exome sequencing and structural analysis of the identified mutations were performed as described (Krauthammer et al., 2012). The RNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA) was used to extract RNA from snap-frozen tumor blocks with (YUDOSO and YULAC) or without (YUCOT and YUSTE) microdissection of tumor tissue. Reverse transcription was performed with the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit from BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA) using 0.8 µg of RNA per reaction. Resulting cDNA was diluted 1:10 and qRT-PCR was conducted using Universal TaqMan Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The following primers were used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions: AXL (Hs0024357_m1), MERTK (Hs01031973_m1), WNT5A (Hs00998537_m1), CDH1 (Hs01023894_ m1), CDH2 (Hs009830566_m1), MITF (Hs01117294_m1), MLANA (Hs00194133_m1), and TYRO3 (Hs00170723_m1), and GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1) (Applied Biosystems).

Gene correlation studies, online databases, and statistical analysis

Kendall’s Tau non-parametric correlation tests were performed on NimbleGen microarray data to determine which genes were concordantly or discordantly expressed in relation to AXL or MERTK. Kendal’s Tau values were computed using the correlation test function in R and P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hotchberg false discovery rate (FDR). Positive Tau values indicate concordance and negative Tau values indicate discordance. A Tau value of zero indicates a random relationship. Based on Kendall’s Tau analysis, genes determined to be significantly associated with AXL or MERTK (P < 0.01) were analyzed in the DAVID to determine whether AXL and MERTK could be linked to different signaling pathways (Huang da et al., 2009a,b). Where indicated, paired, two-tailed t-tests were used to evaluate differences between samples.

The Oncomine database was used to assess MERTK expression in melanoma as has been described (Rhodes et al., 2004). The Human Protein Atlas database was used to evaluate AXL and MERTK expression in melanoma tumor cores as determined by immunohistochemistry (Uhlen et al., 2010). All cores were assessed by a certified pathologist and were given a grade ranging from 0 (no expression) to 3 (high expression). The percentage of stained cells was also quantified.

shRNA and lentiviral infection

shRNA targeting MERTK (RHS3979-9569272, Mer862; RHS3979-9569275, Mer865; Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA) (Keating et al., 2010) and scrambled shRNA control (plasmid 1864) (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) were used where indicated. Lentivirus was generated as described (Tworkoski et al., 2011). All infections were carried out at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Where indicated, cells were selected in 1 µg/ml puromycin.

Cell proliferation, clonogenic assays, and migration assays

CellTiter-Glo (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to measure cell proliferation and 8-micron transwell inserts (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used to assess cell migration as described (Tworkoski et al., 2011). Additional proliferation studies were conducted by seeding 5000 cells in a 24-well plate 24 h after lentiviral infection and counting distinct wells at given timepoints. Clonogenic assays were performed by seeding 4000 cells in 60 mm dishes 24 h after infection. Cells were incubated for 10 days, then fixed and stained. Colony number and size were measured with ImageJ software. All assays were performed in triplicate and the average results are shown.

Flow microfluorimetry analysis

Cells seeded in 6-well plates were infected as previously described. Where indicated, cells were treated with 15% DMSO for 24 h to generate a control population of dead cells. Flow analysis was performed using the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, but only 2 µl of propidium iodide was used per sample. Results of flow experiments were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). All assays were performed in triplicate and a representative result is shown for each experiment.

Induction of AXL, MERTKWT, MERTKP802S, and AKT expression

The pINDUCER system (Meerbrey et al., 2011) was used for expression of AXL, MERTKWT, and MERTKP802S in melanoma cells. Briefly, AXL and MERTK in pDONR backbones were purchased from Genecopoeia (Rockville, MD, USA). The MERTKP802S construct was generated using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and primers (forward gcggggaatgactccctatagtggggtccag, reverse cgccccttactgagggatatcaccccaggtc) produced by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IO, USA). The requisite cDNA was inserted into the pINDUCER backbone using the Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). Virus stocks were produced by cotransfecting 293T cells with 1.1 µg of pINDUCER cDNA, 275 ng of VSVg, 280 ng of HGPM2, 275 ng of RaII, and 280 ng of Tat1b per 60 mm dish. Supernatants were collected daily for 2 days and pooled. The pINDUCER backbone and the packaging and envelope plasmids were a generous gift from Dr. Stephen Elledge, Harvard University. Experimental infections were performed at a MOI of five. Where indicated, expression of pINDUCER vectors was induced using 100 ng/ml doxycycline.

Analysis of MERTK in 293T cells was performed by transfecting 3 µg of MERTK or GFP in the pReceiver-M14 backbone (GeneCo-poeia) into 293T cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The MERTKP802S pReceiver-M14 construct was generated using site-directed mutagenesis as described above.

Myristoylated AKT in a pcDNA3 backbone was generously provided by Dr. William Sessa, Yale University. AKT or empty pcDNA3 constructs were transfected into cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were stably selected using 500 µg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) for 10 days.

Kinase assays

293T cells were transfected with MERTKWT or MERTKP802S in pReceiver-M14 as described above. Kinase assays were performed by lysing cells 24 h after transfection without phosphatase inhibitors. MERTK was immunoprecipitated from 800 µg of cell lysate (described above) and split into 8 equal parts (100 µg each) in kinase buffer (50 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.3, 3 mM MnCl2, 20 mM MgCl2, with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich) added immediately before use). Six parts were incubated with 100 µM adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP) (Roche; Branford, CT) in kinase buffer at room temperature for the indicated period of time before immunoblotting with anti-pTyr. One part was incubated in kinase buffer without ATP before immunoblotting for pTyr as a negative control. The remaining fraction of each immunoprecipitation (containing 100 µg of protein) was immunoblotted for MERTK. Ratios of pTyr to MERTK were obtained using ImageJ.

Immunofluorescence

Twenty-four hours after 293T cells were transfected with GFP in pReceiver-M14 (described above), the transfection efficiency was visually assessed using fluorescence microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Individuals with metastatic melanoma have a median survival time of approximately 8 months. MERTK has been suggested as a therapeutic target in various cancer subtypes but has not been examined in melanoma pathogenesis. In this study, we show that MERTK regulates melanoma cell survival and migration. We elucidate the differential affects of MERTK and AXL on melanoma cells and describe a novel MERTK mutation that regulates cell motility. These data suggest that MERTK is a therapeutic target for melanoma treatment and offer novel insight into the physiological roles of MERTK and AXL.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kelly Flynn for her assistance in performing flow analysis and both Jing Zhou and Dr. Keith Choate for generously providing keratinocytes. We are grateful to Steve Elledge and Bill Sessa for providing plasmids, and to Carla Rothlin for her input on TAMs. We would also like to thank Dr. Ruth Halaban for her leadership of the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer and for her support and many helpful discussions throughout the course of this work. This study was supported by the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer P50 CA121974, the Harry J Lloyd Charitable Trust (DFS, KT), and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (KT).

Related work supporting the importance of MERTK in melanoma was recently reported by Schlegel et al. (J. Clin. Invest., Epub).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. AXL and MERTK are differentially expressed in melanoma and correlate with different gene expression patterns.

Figure S2. MERTK expression increases during melanoma development, and targeting MERTK is detrimental to melanoma cells.

Figure S3. Prolonged MERTK knockdown affects cell migration but not proliferation, survival, or AKT signaling.

Figure S4. Transfection of GFP and MERTK constructs into 293T cells.

Table S1. AXL and MERTK expression in melanoma.

Table S2. Genes correlated with expression of TAM family members.

Table S3. AXL and MERTK are associated with different transcriptional signatures.

Table S4. Relative gene expression in AXL- and MERTK-positive cell lines.

Table S5. Pathways associated with AXL expression.

Table S6. Pathways associated with MERTK expression.

Table S7. MERTK regulates melanoma cell survival.

References

- Furdui CM, Lew ED, Schlessinger J, Anderson KS. Autophosphorylation of FGFR1 kinase is mediated by a sequential and precisely ordered reaction. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal A, Li Y, Thompson DA, Weir J, Orth U, Jacobson SG, Apfelstedt-Sylla E, Vollrath D. Mutations in MERTK, the human orthologue of the RCS rat retinal dystrophy gene, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:270–271. doi: 10.1038/81555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu MM, Kirsch KH, Shishido T, Zong C, Hanafusa H. Biological effects of c-Mer receptor tyrosine kinase in hematopoietic cells depend on the Grb2 binding site in the receptor and activation of NF-kappaB. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1171–1181. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goydos JS, Gorski DH. Vascular endothelial growth factor C mRNA expression correlates with stage of progression in patients with melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:5962–5967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge KL, Luft JC, Dawson TL, Kozlowska E, Mahajan NP, Varnum B, Earp HS. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: prevention of apoptosis and alteration of cytoskeletal architecture without stimulation or proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24057–24066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Lage H. A Web-based data warehouse on gene expression in human malignant melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:394–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek KS, Eichhoff OM, Schlegel NC, Dobbeling U, Kobert N, Schaerer L, Hemmi S, Dummer R. In vivo switching of human melanoma cells between proliferative and invasive states. Cancer Res. 2008;68:650–656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SJ, Powell MJ, Franci C, et al. Multiple roles for the receptor tyrosine kinase axl in tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9294–9303. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009a;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009b;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Finerty P, Jr, Walker JR, Butler-Cole C, Vedadi M, Schapira M, Parker SA, Turk BE, Thompson DA, Dhe-Paganon S. Structural insights into the inhibited states of the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;165:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucthagowder V, Meyer R, Mullins C, Nagarajan R, Dipersio JF, Vij R, Tomasson MH, Kulkarni S. Resequencing analysis of the candidate tyrosine kinase and RAS pathway gene families in multiple myeloma. Cancer Genet. 2012;205:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating AK, Kim GK, Jones AE, et al. Inhibition of Mer and Axl receptor tyrosine kinases in astrocytoma cells leads to increased apoptosis and improved chemosensitivity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1298–1307. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn AD, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Roth RA. Expression of a constitutively active Akt Ser/Thr kinase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes stimulates glucose uptake and glucose transporter 4 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31372–31378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1006–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Yen CY, Liu SY, Chen CK, Chiang CF, Shiah SG, Chen PH, Shieh YS. Axl is a prognostic marker in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011;19:500–508. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1985-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AM, Hari DM, Morton DL. Surgery for distant melanoma metastasis. Cancer. J. 2012;18:176–184. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31824bc981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Xiao X, Li S, Jia X, Wang P, Guo X, Jiao X, Zhang Q, Hejtmancik JF. Detection of variants in 15 genes in 87 unrelated Chinese patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Kung HJ. Mitogenic signals and transforming potential of Nyk a newly identified neural cell adhesion molecule-related receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:6582–6592. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L, Templeton D, Kung HJ. Identification of the major autophosphorylation sites of Nyk/Mer, an NCAM-related receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18355–18362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linger RM, Keating AK, Earp HS, Graham DK. TAM receptor tyrosine kinases: biologic functions, signaling, and potential therapeutic targeting in human cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2008;100:35–83. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linger RM, DeRyckere D, Brandao L, Sawczyn KK, Jacobsen KM, Liang X, Keating AK, Graham DK. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase is a novel therapeutic target in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2678–2687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lu Q, Lemke G. Homeostatic regulation of the immune system by receptor tyrosine kinases of the Tyro 3 family. Science. 2001;293:306–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1061663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Gore M, Zhang Q, et al. Tyro-3 family receptors are essential regulators of mammalian spermatogenesis. Nature. 1999;398:723–728. doi: 10.1038/19554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan NP, Earp HS. An SH2 domain-dependent, phosphotyrosine-independent interaction between Vav1 and the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase: a mechanism for localizing guanine nucleotide-exchange factor action. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42596– 42603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannava S, Grachtchouk V, Wheeler LJ, Im M, Zhuang D, Slavina EG, Mathews CK, Shewach DS, Nikiforov MA. Direct role of nucleotide metabolism in C-MYC-dependent proliferation of melanoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2392–2400. doi: 10.4161/cc.6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerbrey KL, Hu G, Kessler JD, et al. The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:3665–3670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019736108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan JP, Frye RA, Cogswell PC, Neubauer A, Kitch B, Prokop C, Espinosa R, 3rd, Le Beau MM, Earp HS, Liu ET. axl, a transforming gene isolated from primary human myeloid leukemia cells, encodes a novel receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:5016–5031. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paccez JD, Vasques GJ, Correa RG, Vasconcellos JF, Duncan K, Gu X, Bhasin M, Libermann TA, Zerbini LF. The receptor tyrosine kinase Axl is an essential regulator of prostate cancer proliferation and tumor growth and represents a new therapeutic target. Oncogene. 2012;32:689–698. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J, Chen N, Wang J, Siu CH. Transendothelial migration of melanoma cells involves N-cadherin-mediated adhesion and activation of the beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4386–4397. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qingxian L, Qiutang L, Qingjun L. Regulation of phagocytosis by TAM receptors and their ligands. Front. Biol. 2010;5:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s11515-010-0034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Fuh KC, Taylor TE, Krieg AJ, Musser M, Yuan J, Wei K, Kuo CJ, Longacre TA, Giaccia AJ. AXL is an essential factor and therapeutic target for metastatic ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7570–7579. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, Barrette T, Pandey A, Chinnaiyan AM. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riess JW, Neal JW. Targeting FGFR, ephrins, Mer, MET, and PDGFR-alpha in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:S1797–S1798. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000407562.07029.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samija I, Lukac J, Maric-Brozic J, Buljan M, Alajbeg I, Kovacevic D, Situm M, Kusic Z. Prognostic value of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and tyrosinase as markers for circulating tumor cells detection in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2010;20:293–302. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32833906b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayan AE, Stanford R, Vickery R, et al. Fra-1 controls motility of bladder cancer cells via transcriptional upregulation of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL. Oncogene. 2012;31:1493–1503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolyer RA, Long GV, Thompson JF. Evolving concepts in melanoma classification and their relevance to multidisciplinary melanoma patient care. Mol. Oncol. 2011;5:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz HM, Camenisch TD, Lemke G, Earp HS, Matsushima GK. Macrophages and dendritic cells use different Axl/Mertk/Tyro3 receptors in clearance of apoptotic cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5635–5642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi M, Catani M, Castellano G, et al. Human cutaneous melanomas lacking MITF and melanocyte differentiation antigens express a functional Axl receptor kinase. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:2448–2457. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer. J. Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemiatkowska AM, Arimadyo K, Moruz LM, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of retinitis pigmentosa in Indonesia using genome-wide homozygosity mapping. Mol. Vis. 2011;17:3013–3024. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworkoski K, Singhal G, Szpakowski S, Zito CI, Bacchiocchi A, Muthusamy V, Bosenberg M, Krauthammer M, Halaban R, Stern DF. Phosphoproteomic screen identifies potential therapeutic targets in melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011;9:801–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, et al. Towards a knowledge-based Human Protein Atlas. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/nbt1210-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuoriluoto K, Haugen H, Kiviluoto S, Mpindi JP, Nevo J, Gjerdrum C, Tiron C, Lorens JB, Ivaska J. Vimentin regulates EMT induction by Slug and oncogenic H-Ras and migration by governing Axl expression in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:1436–1448. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Moncayo G, Morin P, Jr, Xue G, Grzmil M, Lino MM, Clement-Schatlo V, Frank S, Merlo A, Hemmings BA. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase promotes invasion and survival in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2012;32:872–882. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeraratna AT, Jiang Y, Hostetter G, Rosenblatt K, Duray P, Bittner M, Trent JM. Wnt5a signaling directly affects cell motility and invasion of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YM, Robinson DR, Kung HJ. Signal pathways in up-regulation of chemokines by tyrosine kinase MER/NYK in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7311–7320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Chen Y, Wang H, Wu H, Lu Q, Han D. Gas6 and the Tyro 3 receptor tyrosine kinase subfamily regulate the phagocytic function of Sertoli cells. Reproduction. 2008;135:77–87. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Wurdak H, Wang Y, et al. A genomic screen identifies TYRO3 as a MITF regulator in melanoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17025–17030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909292106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.