Abstract

Objective

To identify case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME), and explore how the validity of case definitions can be evaluated in the absence of a reference standard.

Design

Systematic review.

Setting

International.

Participants

A literature search, updated as of November 2013, led to the identification of 20 case definitions and inclusion of 38 validation studies.

Primary and secondary outcome measure

Validation studies were assessed for risk of bias and categorised according to three validation models: (1) independent application of several case definitions on the same population, (2) sequential application of different case definitions on patients diagnosed with CFS/ME with one set of diagnostic criteria or (3) comparison of prevalence estimates from different case definitions applied on different populations.

Results

A total of 38 studies contributed data of sufficient quality and consistency for evaluation of validity, with CDC-1994/Fukuda as the most frequently applied case definition. No study rigorously assessed the reproducibility or feasibility of case definitions. Validation studies were small with methodological weaknesses and inconsistent results. No empirical data indicated that any case definition specifically identified patients with a neuroimmunological condition.

Conclusions

Classification of patients according to severity and symptom patterns, aiming to predict prognosis or effectiveness of therapy, seems useful. Development of further case definitions of CFS/ME should be given a low priority. Consistency in research can be achieved by applying diagnostic criteria that have been subjected to systematic evaluation.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Primary Care, Statistics & Research Methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of our study is the systematic methods used to identify and appraise articles presenting and evaluating case definitions of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis.

We used systematic and transparent approaches to extract data, categorise the studies according to prespecified models and to analyse and compare the data.

The included validation studies showed considerable methodological weaknesses and inconsistent results, and it is therefore difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a serious disorder characterised by persistent postexertional fatigue and substantial symptoms related to cognitive, immune and autonomous dysfunction.1 2 Disease mechanisms are complex,3 with no single causal factor identified. Yet there are indications that infections4–8 and immunological dysfunction9 contribute to development and maintenance of symptoms, probably interacting with genetic10 and psychosocial11–13 factors.

Studies have identified pathological patterns and structures of the central nervous system,14 15 dysregulation of body temperature and blood pressure16 17 and dysfunctional stress hormonal systems18 19 in patients with CFS compared with normal controls. None of these appears sufficiently consistent to constitute a diagnostic test, and case definitions (diagnostic criteria) are therefore used to define the CFS diagnosis. When case definitions are developed, the context of application must be considered, since different properties are needed for case definition intended for research purposes compared with case definitions used to diagnose individual patients. It is also necessary to consider whether a broad (ie, sensitive criteria ensuring that we do not miss relevant cases) or narrow (ie, specific criteria ensuring that all positive cases are definite) approach is most appropriate.

Holmes et al20 coined the term ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ in 1988, as an alternative to ‘The chronic Epstein-Barr virus syndrome’. Since this case definition—the CDC-1988/Holmes Criteria—was presented in 1988,20 numerous revisions have been developed, aiming for distinctive and reliable identification of individuals who represent a homogenous and consistent phenotype of the hypothesised disease entity, consistent with pathophysiological and psychosocial findings. Currently, the term ‘myalgic encephalomyelitis’ (ME) is commonly used to conceptualise a specific neuroimmunological condition, assumed to be more severe and less psychologically attributed than CFS.21 In 2003, Carruthers et al presented the Canadian-2003 Criteria for diagnosis of ME/CFS.22 A revised version was presented as International Consensus Criteria (the ICC-2011 Criteria) for ME,23 claiming to be a selective case definition for identification of patients with neuroimmune exhaustion with a pathologically low threshold of fatigability and symptom flare after exertion. The assertion that CFS and ME are different clinical entities is disputed. Below, we will pragmatically apply the term CFS/ME.

Johnston et al24 conducted a systematic review of the adoption of CFS/ME case definitions to assess the prevalence and identified eight different case definitions. There is no general agreement on a reference standard for diagnosis, and no diagnostic test is available. Bossuyt et al25 include case definitions in their understanding of the term ‘test’, emphasising that diagnostic tests are highly dynamic and need rigorous evaluation before they are introduced into clinical practice.26

The objectives of our study were to explore strategies for evaluation of accuracy and concept validity of different case definitions for CFS/ME in the absence of a reference standard. First, we wanted to conduct a systematic review to identify and describe different case definitions (sets of diagnostic criteria) for CFS/ME. Second, we wanted to explore differences between various case definitions by identifying and reviewing validation studies.

Materials and Methods

Protocol and registration

We developed a protocol for our study. However, we did not publish or register it.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies presenting or validating case definitions for CFS/ME for adult populations (>18 years). No language restrictions were employed.

Information sources and search

We searched Ovid MEDLINE from 1946, Ovid EMBASE from 1980, Ovid PsycINFO from 1806, Ovid AMED from 1985, The Cochrane Library from 1898, CINAHL from 1981 and PEDRO from 1929, using subject headings and text words (see online supplementary appendix 1). All searches were up to date as of 25 November 2013. We checked the reference lists of all included articles and searched for unpublished and ongoing studies by correspondence with authors and field experts.

Study selection

To select publications eligible for this review, two authors independently read all titles and abstracts in the records retrieved by the searches. We obtained publications in full text if the abstract was deemed eligible by at least one review author. At least two authors independently read the full text papers and selected studies according to the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between review authors was resolved by discussion between the two review authors or, if necessary, by involving all authors.

Data collection process

First, we listed all the identified case definitions for CFS/ME. One author gathered information about citation from ISI and Google Scholar to indicate the impact or widespread of use, but we made no attempt to assess or rank the quality of the case definitions at this stage.

To facilitate the validity assessment, we developed a framework consisting of three different models.

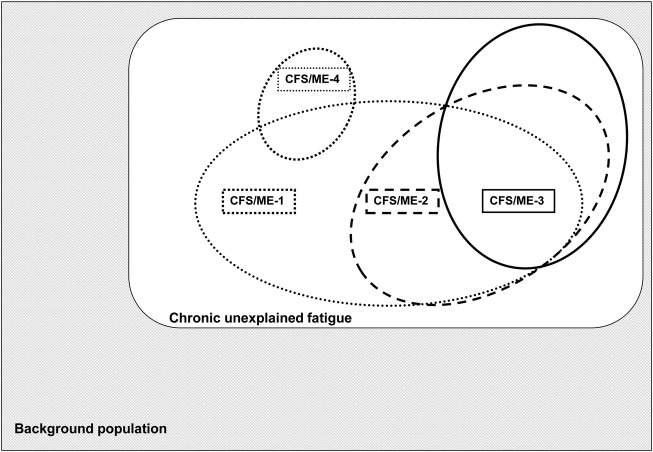

Model A includes studies with independent application of different case definitions on the same population (figure 1). This model presents the interrelationship between subpopulations identified by different case definitions.

Figure 1.

Model A: evaluation design with independent application of several case definitions on the same background population (CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis).

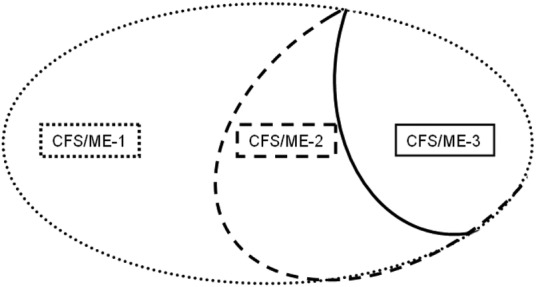

Model B includes studies where patients diagnosed with CFS/ME with one set of diagnostic criteria are diagnosed sequentially with other case definitions assumed to have increasing specificity (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model B: evaluation design where different case definitions with assumed increasing specificity are applied sequentially on the same population (CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis).

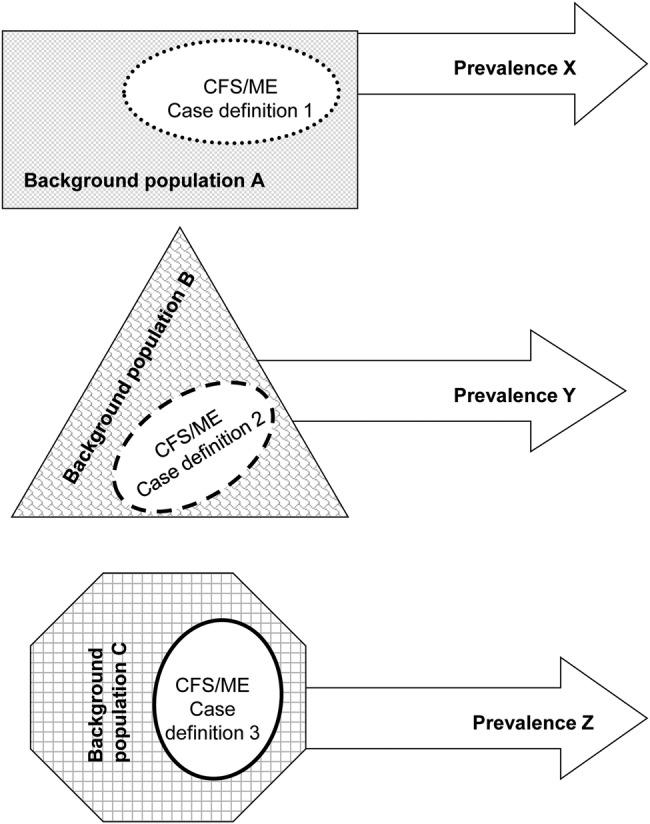

Model C includes surveys or cross-sectional studies estimating the prevalence of CFS/ME by applying different case definitions on different populations (figure 3). These studies do not directly compare different case definitions, but may be used for proxy evaluation, similar to the strategy applied by Johnston et al.24 27

Figure 3.

Model C: evaluation design with indirect comparisons of prevalence estimates from several case definitions applied on different populations (CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis).

Two authors reviewed all potentially relevant validations studies, and categorised them according to model A, B or C. Any disagreement between review authors at this stage was resolved by reaching consensus in the author group.

Risk of bias in individual studies

To differentiate between studies with higher and lower risk of bias, we critically appraised all included validation studies according to check lists: Studies comparing two or more case definitions directly (ie, model A or B) were appraised according to the QUADAS criteria28 (patient selection, index test, reference standard, flow and timing). For evaluation of prevalence studies (ie, model C), we used an outline for assessment of external and internal validity (11 items) of prevalence studies.29

Analysis

Participation in prevalence studies, surveys and questionnaires vary across the included studies. Non-response is known to introduce bias, and methods to adjust for low response rates are available.30 In studies affected by non-response, we have reported adjusted estimates whenever applicable. If adjusted estimates were unavailable, we have defined the proportion as the number of cases divided by the number of responders. We estimated 95% CIs for all proportions by using the Clopper-Pearson exact binomial method. We used R software V.3.0.0 and the rmeta package for statistical computations and plotting.31 32

Results

Study selection

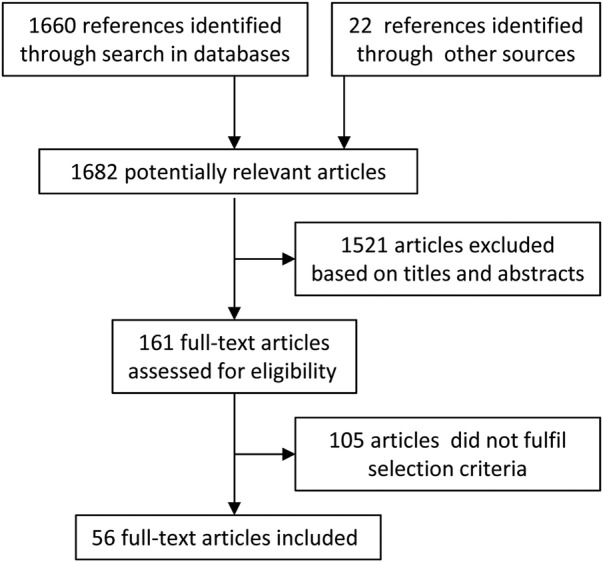

Our systematic literature search identified 1660 unique references, of which 56 articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria (figure 4). Twenty articles present different case definitions of CFS/ME for research or clinical practice20 22 23 33–49 (table 1). Furthermore, 38 studies were classified as validation studies, contributing data of sufficient quality and consistency for evaluation of different case definitions according to our inclusion criteria.

Figure 4.

Flow chart summarising the selection process.

Table 1.

Case definitions for CFS/ME

| Case definitions (chronologically) | Developed from other criteria or definitions? | Institution and country of first author | CITATIONS* ISI/Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDC-1988/Holmes et al20 | Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA | 1106/1542 | |

| ME-1988/Ramsey42 | Royal Free Hospital, London, UK | 6/51 | |

| London-1990/Dowsett et al37 | Royal Free Hospital, London, UK | 55/88 | |

| Australian-199044 | The Prince Henry Hospital, Little Bay, Australia | 230/343 | |

| Postviral fatigue syndrome-199043 | Raigmore Hospital, Inverness, UK | 14/28 | |

| Oxford-199140 | University of Oxford, Oxford, UK | 476/667 | |

| London ME-1994/National Task Force Guidelines48 | National Task Force, Bristol, UK | No records | |

| CDC-1994/Fukuda et al39 | CDC-1988 | Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA | 1860/3006 |

| Working case definition-199638 | CDC-1988 | Brigham and Women's Hospital Massachusetts, USA | 78/138 |

| CFS-199849 | CDC-1994 | Medical College of Wisconsin, USA | 8/23 |

| Canadian-200322 | Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Canada | 69/233 | |

| Empirical CDC-2005/Reeves et al63 | CDC-1994 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA | 73/154 |

| Empirical-200741 | DePaul University, Chicago, USA | 5/14 | |

| Brighton Collaboration-200735 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA | 1/5 | |

| NICE-2007 Guidelines46 | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London, UK | No records/23† | |

| The Nightingale Definition of ME-2007/Hyde45 | The Nightingale Research Foundation, Canada | No records/5 | |

| ECD-200834 | Southampton, Hampshire, UK | 2/4 | |

| Revised Canadian-201047 | CDC-1994, Empirical CDC-2005, Canadian-2003 | DePaul University, Illinois, USA | 8/18 |

| ICC-201123 | Canadian-2003 | Independent, Canada | 4/16 |

| ME-201133 | London-1990, ME-1988, The Nightingale Definition of ME-2008 | DePaul University, Illinois, USA | 1/1 |

*Searched 23 May 2012.

†Summary of the NICE Guidelines in: diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2007;335:446.

CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; ICC, International Consensus Criteria; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis; ECD, epidemiological CFS/ME definition.

The degree to which the different case definitions had been applied in research and clinical guidelines varied widely, with CDC-1994/Fukuda et al39 as the most frequently cited case definition of CFS/ME.

Thirteen of the 20 identified case definitions had been assessed in one or more validation studies.20 22 23 33 34 36 37 39–41 43 44 47 For seven case definitions, no foundation for validation could be identified. We did not identify any study which rigorously assessed the reproducibility or feasibility of the different case definitions.

Independent application of several case definitions on the same population (model A)

Five studies (table 2) applied several case definitions on the same population, but only one of these reported data in a way that made it possible to compare the case definitions.50 51 Nacul et al50 used general practitioner (GP) databases and questionnaires and identified 278 patients with unexplained chronic fatigue (CF) conforming to one or more of the case definition applied, that is, CDC-1994/Fukuda et al,39 Canadian-200322 or ECD-2008.34 Most of the patients who were positive according to the Canada criteria (C+) were also positive using the Fukuda criteria (F+). Forty-seven per cent of the Fukuda-positive patients were also positive according to the Canada criteria. Patients who were positive to the Canada and Fukuda (C+/F+) reported a higher level of symptoms than those who were (F+/C–). The authors did not identify differences in the distribution of triggering factors.50

Table 2.

Studies presenting prevalence estimates* by independent application of several case definitions on the same population (model A)

| First author, year, country | Data collection | Prevalence (95% CI) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nacul,50 2011, UK | 609 possible cases electronically identified in databases of 29 GP practices. 70 excluded after clinical revision (explained fatigue), 135 refusals and 126 non-cases | ECD: 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) Canada: 0.10 (0.09 to 0.12) Fukuda: 0.19 (0.17 to 0.21) |

| Bates,56 1993, USA | 995 consecutive GP visitors invited—94% screened by a questionnaire to detect major fatigue. Selected patients further evaluated by questionnaires, physical examinations and interviews | Holmes: 0.3 (0.1 to 0.9) Oxford: 0.4 (0.1 to 1.1) Australia: 1.1 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| Kawakami,57 1998, Japan | All adults (n=508) in Town A, Kofu-city, were invited to participate in this structured psychiatric diagnostic interview survey. 137 (27%) completed the study | Holmes: 0.0 (0.0 to 2.7) Fukuda: 1.5 (0.2 to 5.2) Oxford: 1.5 (0.2 to 5.2) |

| Lindal,55 2002, Iceland | Survey sent to 4000 randomly selected adult participants—63% responded. Questionnaire included questions on all items in the four case definitions. Diagnoses were set electronically based on received responses. No medical tests or examinations were undertaken | Holmes 0.0 (0.0 to 1.5) Fukuda: 2.1 (1.6 to 2.8) Oxford: 3.7 (3.2 to 4.6) Australia: 7.6 (6.6 to 8.7) |

| Wessely,54 68 1997, UK | 2363 patients followed in a cohort study—84% completed. Fatigued participant subjected to detailed questionnaires, interviews and laboratory testing. Separate estimates reported for inclusion/exclusion of psychiatric comorbidity | Holmes: 1.2 (0.5 to 1.8) Australia: 1.4 (0.8 to 2.0) Oxford: 2.2 (1.4 to 3.0) Fukuda: 2.6 (1.7 to 3.4) |

*Prevalence estimates were calculated with the number of responders in the denominator. The choice of denominator may have large implications with regard to the subsequent prevalence estimate, particularly in studies with low response rate. Hence, depending on the actual response rate, estimates presented for each study may be biased.

GP, general practitioner.

None of the other four studies in this group reported data on the correlation between case definitions, patient profile and symptom burden. Application of CDC-1988/Holmes case definition was consistently associated with lower prevalence estimates than CDC-1994/Fukuda, Oxford-1991 and Australian-1990 criteria across these four studies. There was no consistent trend for the other case definitions, but the studies were heterogeneous regarding the application of different case definitions and data collection (table 2). This observation suggests that prevalence numbers obtained by different case definitions should be controlled according to diagnostic procedure, cut-off points and reasons for exclusions before concluding on differences.

Different case definitions with assumed increasing specificity applied sequentially on the same population (model B)

Twelve studies (table 3) sequentially applied different case definitions on the same population. In these studies, patients were screened by using an evaluation standard. Subsequently, test-positive individuals were screened with one or more comparators. Nine of the 12 studies applied CDC-1994/Fukuda as the evaluation standard, and then tested Fukuda-positive patients with CDC-1988/Holmes, Canadian-2003, ICC-2011, ME-2011, Empirical-2006/Reeves, London-1990/Dowsett or Neurasthenia case definitions.

Table 3.

Conformity of prevalence estimates in studies where patients diagnosed with CFS/ME with one set of diagnostic criteria are diagnosed sequentially with other case definitions (model B)

| Study recruitment | Case definitions | Conformity* (95% CI) | Symptom and burden profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brimacombe et al,69 USA Fukuda-positive from register |

Fukuda† (n=200) Holmes (n=171) |

1 0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) |

(F+/H–) patients do not endorse infectious-type symptoms as often or to the same degree of severity as (F+/H+) patients |

| Jason et al,70 USA Fukuda-positive from register |

Fukuda† (n=32) Holmes (n=14) |

1 0.44 (0.26 to 0.62) |

(F+/H+) patients with more symptoms and functional impairment than (F+/H–). No difference in psychological comorbidity |

| Jason et al,52 USA Fukuda-positive from register |

Fukuda† (n=32) Canada (n=23)‡ |

1 0.63 (0.44 to 0.79) |

C+ patients have less psychiatric comorbidity, more physical function impairment, are more fatigued with more neurological symptoms than (F+/C–) patients |

| Jason et al,33 USA Fukuda-positive recruited from many sources |

Fukuda† (n=113) Canada (n=57) ME-2011 (n=27) |

1 0.50 (0.41 to 0.60) 0.24 (0.16 to 0.33) |

(F+/C+) patients had more functional impairments, and physical, mental and cognitive problems than (F+/C–) patients. (F+/ME+) patients had more functional impairments, and more severe physical and cognitive symptoms than (F+/ME–) patients |

| Fluge et al,9 Norway Fukuda-positive patients recruited to trial |

Fukuda† (n=30) Canada (n=28) |

1 0.93 (0.78 to 0.99) |

Not reported |

| Jason et al,71 USA Register |

Fukuda† (n=24) Reeves empirical Canada |

Of 24 F+ and 84 F-patients empirical criteria and Canada identified 79 and 87% correctly | Canadia-2003 case definition appears to select more cardinal and central features of the illness than Empirical CDC-2005/Reeves case definition |

| Jason et al,65 USA Register |

Fukuda† (n=27) Reeves emp. (n=41)§ |

1 1.00 (0.87 to 1.00) |

Empirical CDC-2005/Reeves case definition led to misclassification of major depressive disorder as CFS |

| Brown et al,53 USA Fukuda-positive recruited from many sources |

Fukuda† (n=113) ICC (n=39) |

1 0.35 (0.26 to 0.44) |

ICC+ patients with more functional impairments and physical, mental and cognitive problems than (F+/ICC–) patients. The ICC+ patients also had greater rates of psychiatric comorbidity |

| Jason et al,72 USA Fukuda-positive from register |

Fukuda† (n=32) Dowsett (n=17)¶ |

1 0.44 (0.26 to 0.62) |

D+ patients appear to be more symptomatic than (F+/D–) patients, especially in the neurological and neuropsychiatric areas |

| White et al,60 UK Oxford-positive patients recruited to trial |

Oxford† (n=641) Fukuda (n=427) London ME (n=329) |

1 0.67 (0.63 to 0.70) 0.51 (0.47 to 0.55) |

Effect of CBT and GET similar regardless of diagnostic group affiliation |

| Wearden et al,73 UK Oxford-positive patients recruited to trial |

Oxford† (n=296) London ME (n=92) |

1 0.31 (0.26 to 0.37) |

Not reported |

| Stubhaug et al,74 Norway Neurasthenia-positive patients recruited to trial |

Neurasthenia† (n=72) Oxford (n=65) Fukuda (n=29) |

1 0.90 (0.81 to 0.96), 0.40 (0.29 to 0.53) |

Not reported |

*The proportion of cases relative to the evaluation standard.

†Evaluation standard.

‡Three of the 23 participants who tested positive according to the Canada criteria were negative according to Fukuda.

§14 of the 37 patients who tested positive according to Reeves were negative according to Fukuda (these 14 patients had a depression diagnosis).

¶Three of the 17 participants who tested positive according to Dowsett were negative according to Fukuda.

CBT, cognitive behavorial therapy; CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; GET, graded exercise therapy; ICC, International Consensus Criteria; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis.

We have taken the actual evaluation standard as a point of departure, and calculated the proportion of these patients still positive when applying other case definitions. Since there are no test negatives for the case definition used as point of departure, true sensitivities or specificities cannot be calculated. Results from two of the studies by Jason et al33 52 suggest that 40–70% of the Fukuda-positive patients are also Canada positives (F+/C+). One study52 concluded that there was less psychiatric comorbidity and more physical functional impairment in the subsample which was positive on both case definitions (F+/C+) than those who were negative according to the Canada criteria (F+/C−). However, the other study33 suggested a higher incidence of mental and cognitive problems among Fukuda-positive patients who were also Canada positive (F+/C+) as compared with the remaining Fukuda-positive but Canada-negative patients (F+/C−). In a separate publication,53 the same Fukuda-positive patients as referred in Jason et al33 were used to contrast ICC-2011. About 34% (95% CI 26% to 44%) of the Fukuda-positive patients were also ICC positives (F+/ICC+). Similar to the (F+/C+) subset, it was found that (F+/ICC+) patients experienced more functional impairments as well as more mental and cognitive problems and higher psychiatric comorbidity than (F+/ICC−) patients.

The comparisons presented in table 3 are associated with high risk of bias as well as random errors, and the results should be interpreted with great caution. For example, two of the included studies reported similar point prevalence according to CDC-1994/Fukuda (2.1% and 2.6%) but reported very different estimates using the Australian-1990 criteria (7.6% and 1.4%).54 55 Sometimes diagnoses were based on questionnaire responses only, sometimes following detailed clinical interviews and laboratory testing. There were also differences in the way similar case definitions were practiced in the various studies, for example, some studies applied a low threshold for exclusion of cases with psychiatric comorbidity, while others did not.

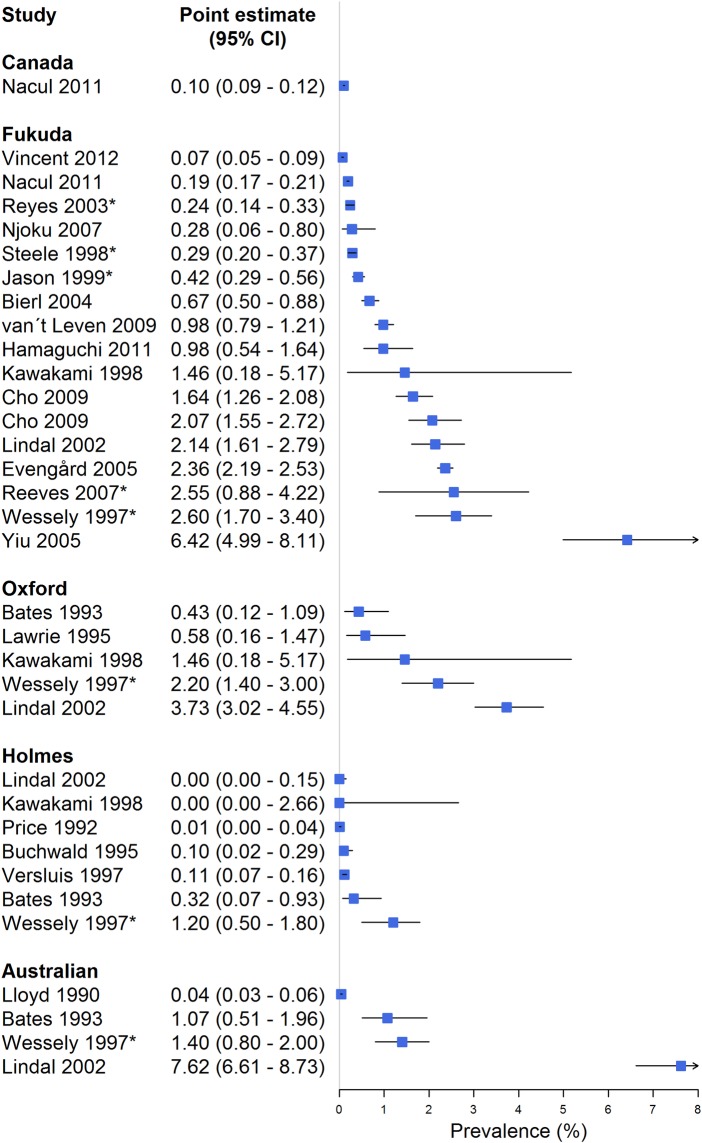

Indirect comparisons of prevalence estimates from several case definitions applied on different populations (model C)

We identified 21 studies (table 4) presenting prevalence estimates for CFS/ME (figure 3), in addition to the five studies presenting prevalence estimates following the application of multiple case definitions (table 2). Based on these studies, we extracted 17 independent estimates of the prevalence following application of the CDC-1994/Fukuda criteria (figure 5).

Table 4.

Studies presenting prevalence estimates for CFS/ME from several case definitions applied on different populations (model C)

| First author, year, country | Case definition | Recruitment strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Bazelmans, 1999,75 The Netherlands | As recognized by GP | Questionnaire to all GPs, prevalence estimated to 0.11% |

| Lloyd, 1990,44 Australia | Australian | Recruited through GP's covering 76 206 patients |

| Buchwald, 1995,76 USA | CDC-1988/Holmes | Postal survey to 4000 randomly selected participants |

| Gunn, 1993,77 USA | CDC-1988/Holmes | Recruited by contact with primary health care providers; prevalence in the range 0.002–0.007% |

| Price, 1992,78 USA | CDC-1988/Holmes | Interview survey with 13 538 participants |

| Versluis, 1997,79 Netherlands | CDC-1988/Holmes | 23 000 patients in GP database |

| Bierl, 2004,80 USA | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Random digit-dialling survey with 7317 respondent |

| Cho, 2009,81 UK | CDC-1994/Fukuda | 2530 consecutive GP visitors |

| Cho, 2009,81 Brazil | CDC-1994/Fukuda | 3921 consecutive GP visitors |

| Evengård, 2005,82 Sweden | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Phone survey of 41 499 participants in a twin register |

| Hamagucchi, 2011,83 Japan | CDC-1994/Fukuda | 3000 random participants in a health check programme |

| Jason, 1999,84 USA | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Phone survey with 18 675 respondents |

| Kim, 2005,85 South Korea | CDC-1994/Fukuda | 1962 consecutive GP visitors |

| Njoku, 2007,86 Nigeria | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Interview survey with 1500 participants |

| Reeves, 2007,64 USA | CDC-1994/empirical | Phone survey with 10 837 responding households |

| Reyes, 2003,87 USA | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Phone survey with 33 997 responding households |

| Steele, 1998,88 USA | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Phone survey with 8004 responding households |

| van't Leven, 2009,89 The Netherlands | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Postal survey to 22 500 randomly selected participants |

| Vincent, 2012,90 USA | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Retrospective medical record review in Olmsted County; 183 841 residents |

| Yiu, 2005,91 China | CDC-1994/Fukuda | Unknown |

| Lawrie, 1995,58 UK | Oxford | Postal survey to 1039 randomly selected participants |

| Ho-Yen, 1991,92 UK | Post viral exhaustion syndrome | Postal survey to 195 GPs; prevalence 0.13% (0.12% to 0.15%) |

CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; GP, general practitioner; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis.

Figure 5.

Forest plot summarising indirect comparisons of prevalence estimates from different case definitions (model C). Studies presenting point prevalence weighted for non-response are asterisked (*).

Our analysis suggests that the population prevalence of CFS/ME according to the CDC-1994/Fukuda case definition probably is less than 1% (range 0.1–6.4%; median 1%), with higher prevalence among consecutive GP attendants than from population studies. Prevalence estimates seemed higher when patients were diagnosed without a preceding medical examination. Prevalence estimates of CFS/ME according to CDC-1988/Holmes case definition seemed lower, with all the studies reporting prevalence estimates ranging from 0.0% to 0.3% (median 0.05%).

Five studies54–58 reported CFS/ME prevalence estimates according to the Oxford-1991 case definition. These estimates ranged from 0.4% to 3.7% (median 1.5%). Four studies44 54–56 reported prevalence estimates according to the Australian-1990 case definition ranging from 0.04% to 7.6% (median 1.2%).

Discussion

We identified 20 studies presenting different CFS/ME case definitions, and 38 studies with data providing access to comparison and evaluation of some of these. Only a minority of existing case definitions had been submitted to comparative evaluations. The validation studies were methodologically weak and heterogeneous, making it questionable to compare the case definitions. The most cited case definition (CDC-1994/Fukuda et al39) is also the most extensively validated one, whereas validation studies are few (Canadian-2003,22 ICC-201123) or missing (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-200746) for recently presented and debated case definitions. We found no empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis that some case definitions more specifically identify patients with a neuroimmunological condition.

Strengths and weaknesses of our study

The main strength of our study is the systematic methods used to identify and appraise articles presenting case definitions of CFS/ME and studies potentially useful to evaluate the case definitions. Furthermore, we have used systematic and transparent approaches to extract data from the validation studies, categorise the studies according to three different models and to analyse and compare the data.

The STARD initiative aims to improve the reporting on studies of diagnostic accuracy, considering any method for obtaining additional information on a patient's health status as a test.25 Owing to the lack of a reference standard, we found this guideline less suitable for review of articles evaluating case definitions for CFS/ME. Still, issues such as study populations, test methods and rationale, technical specifications for application of the test, statistical methods for comparing measures of accuracy and uncertainty, estimates of diagnostic accuracy, variability and clinical applicability25 are relevant also for our analysis.

The validation studies we identified were small with considerable methodological weaknesses and inconsistent results. Only one study held a level of rigour where independent application of several case definitions was conducted on the same population (model A).50 Such a study should ideally be based on a population sample rather than a GP practice database, and should compare a selection of currently applied and debated case definitions, such as CDC-1994/Fukuda, Oxford-1991, Canadian-2003 and NICE-2007.

The QUADAS criteria28 demonstrate that model B is an evaluation strategy prone to several sources of bias. First, the spectrum of patients subjected to the comparator is selected and not representative of the population receiving the test if it is used alone. Second, as comparators were mostly applied subsequently to the evaluation standard, the clinical evaluations were not independent. The estimates from two of the Jason studies33 52 suggest a comparable correspondence (40–70% of the F+ are also C+) with the results presented by Nacul et al.50 Yet, model B gives no or limited information regarding those who screened negative in the first place. We do not know whether some of those might have had a positive diagnosis if screened with one of the other case definitions.

We are even more prone to bias when exploring the consistency of different case definitions through indirect comparisons of prevalence estimates obtained from different populations (model C), and great caution is needed when such proxy comparisons are undertaken. For example, two of the included studies reported similar point prevalence according to CDC-1994/Fukuda (2.1% and 2.6%), but reported very different estimates following the application of the Australian-1990 criteria (7.6% and 1.4%).54 55 This inconsistency can be explained by major methodological differences seen across the included studies. Our sample includes studies in which a diagnosis of CFS/ME is made on the basis of either questionnaire responses or clinical interview. Previous studies suggest that patients who receive a standardised questionnaire report considerably more symptoms than when asked to report their symptoms spontaneously.59 There are several other sources to this between study heterogeneity, such as recruitment strategy, response rate and strategies for non-response adjustment. We were not able to identify the most important one. However, Johnston et al27 performed an interesting subgroup analysis in their meta-analysis of 14 studies applying the CDC-1994/Fukuda case definition, and found that the pooled prevalence for self-reporting assessment was 3.28% (95% CI 2.24% to 4.33%) compared with 0.76% (95% CI 0.23% to 1.29%) for clinical assessment. Prevalence was lower in community samples (0.87%; 0.32% to 1.42%) than in primary care samples (1.72%; 1.40% to 2.04%). The prevalence estimates based on self-reports showed high variability, while clinically assessed estimates were more consistent, especially in the community samples.

The utility of case definitions and diagnoses

The utility of a diagnosis is linked to the potential effects of being diagnosed (eg, benefits and harms of the patient's role, access to treatment and insurance). More importantly, a diagnosis is useful if it is linked to valid information regarding prognosis or outcomes of therapy. Reitsma et al26 suggest clinical test validation as an alternative paradigm for evaluation of a diagnostic test when an acceptable reference standard is missing. Hence, primary studies and systematic reviews on prognosis and therapy are alternative sources to evaluate the usefulness of different case definitions of CFS/ME. We have identified only one such publication, the PACE trial.60 Here, participants were diagnosed according to the Oxford-1991 criteria, Empirical criteria-2007/Reeves and London ME-1994/National Task Force criteria, and then randomised to either standard medical treatment, graded exercise therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy or pacing. The results showed that the effectiveness of the treatments was similar across groups, irrespective of the case definition which had been used. Fluge et al9 applied the CDC-1994/Fukuda and retrospectively added the Canada criteria in their study on the effects of rituximab in CFS with comparable results. In a recent publication, Maes et al21 measured symptom severity, selected biomarkers and postexertional malaise in 144 patients with CF, of whom 107 fulfilled the CDC-1994/Fukuda criteria of CFS/ME. They claimed that CF, CFS and ME are distinct categories, although stating that patients group together in one continuum with no clear boundaries between them.21 Such studies would be even more useful if outcomes of specific treatment modes had also been tested.

A study comparing the prognosis of different diagnostic labels of fatigue found that patients with ME had the worst prognosis while patients with postviral fatigue syndrome had the best.61 This could mean that the patients destined to the worst prognosis were labelled with the ME diagnosis, or it might be explained as an adverse effect of being labelled with ME. The authors found no significant difference in recorded fatigue before the diagnosis of CFS and ME, and the data in this retrospective study supported the hypothesis of the labelling effect. Another study found that patients who attributed their fatigue to ME were more fatigued and more handicapped in relation to home, work, social and private leisure activities than patients who attributed their fatigue to psychological or social factors.62

Broad or narrow case definitions?

Ideally, correspondence validity between test and target should be 100% for sensitivity (the capacity to identify patients in the target group) and specificity (the capacity to rule out patients who do not belong to the target group). More often, there is a trade-off between these measures, depending on the purpose of diagnosis. Emphasising sensitivity implies a risk of overdiagnosis, which dilutes the actual diagnostic concept, while emphasising specificity implies a risk of underdiagnosis, dismissing patients who might benefit from treatment. Development of more exclusive case definitions for CFS/ME has been proposed, claiming that existing case definitions do not select homogenous sets of patients.23 More specifically, Oxford-1991, Fukuda-1994 and NICE-2007 have been criticised, especially by patient organisations, for undue overlap with psychopathology. Proponents of recent case definitions, such as Canada-2003 and ICC-2011, claim to achieve a narrow selection of patients with ME conforming to a hypothesised specific pathophysiology. Our review demonstrates, however, that these case definitions do not necessarily exclude patients with psychopathology.

A lesson could be learnt from Reeves, who tried to elaborate the CDC1994/Fukuda definition and bring methodological rigour into the diagnostic criteria by scores from standardised and validated instruments.63 The Empirical-2006/Reeves case definition led to a tenfold prevalence estimate as compared with the CDC1994/Fukuda definition,64 probably due to misclassification and inclusion of patients with major depressive disorder.65 The purpose of rigour had not been achieved, and the Empirical-2006/Reeves case definition was never broadly implemented. According to our review, it is uncertain whether a more homogenous subset of patients can be achieved with the Canada-2003 and ICC-2011 case definitions. The authors of the latter paper write: “Collectively, members have approximately 400 years of both clinical and teaching experience, authored hundreds of peer-reviewed publications, diagnosed or treated approximately 50 000 patients with ME and several members coauthored previous criteria.”23 This declaration is no validity criterion and provides no guarantee that the case definition works according to the intentions.

Case definitions for research or clinical practice?

Research requires uniform and reproducible criteria, suitable for unambiguous definitions of the target population. Another concern is to compare studies across time and nations. These are arguments for an inclusive case definition, preferably one which has been in use for a while, and for which validation studies are available. In CFS/ME research, the Oxford-1991 and CDC-1994/Fukuda are the most frequently used case definitions. Our review indicates that the former might be more inclusive, with lower specificity than the latter, although the impact of this is unclear. Proponents for more restrictive case definitions dismiss findings from treatment studies documenting effects of cognitive behavioural treatment or graded exercise therapy for patients diagnosed with the Oxford-1991 or CDC-1994/Fukuda case definitions.66 Their claim is that for a more exclusive selection of patients with ME, defined according to specific hypothesised pathophysiology, the side effects of these treatment modalities are hazardous. So far, however, treatment studies based on the Canada-2003 or ICC-2011 case definitions are not available.

Case definitions for clinical practice should be research based, validated and manageable to provide a tool which can relieve patient's uncertainty, indicate the most appropriate treatment and prevent adverse effects and waste of healthcare resources of unnecessary treatment and diagnostic procedures.67 They should be founded on available knowledge regarding the mechanisms of the actual condition, validated through credible and transparent processes and presented in a format which can be implemented in everyday practice. An argument for more inclusive case definitions for CFS/ME would be the issue of treatment, since existing evidence indicates that side effects of cognitive behavioural treatment or graded exercise therapy are negligible. For this context, the CDC-1994/Fukuda case definition appears suitable, with the NICE-2007 as a good candidate for validation studies.

Implications for research and clinical practice

On the basis of our review, we argue that development of further case definitions of CFS/ME should be given low priority, as long as causal explanations for the disease are limited. It might still be useful to classify patients according to severity and symptom patterns, aiming to identify characteristics of patients that might predict differences in prognosis or expected effects of therapy.

It is likely that all CFS/ME case definitions capture conditions with different or multifactorial pathogenesis and varying prognosis. The futile dichotomy of ‘organic’ versus ‘psychic’ disorder should be abandoned. Most medical disorders have a complex aetiology. Psychological treatments are often helpful also for clear-cut somatic disorders. Unfortunately, patient groups and researchers with vested interests in the belief that ME is a distinct somatic disease seem unwilling to leave the position that ME is an organic disease only. This position has damaged the research and practice for patients suffering from CFS/ME.

Conclusions

Our review provided no evidence that any of the case definitions identify patients with specific or ‘organic only’ disease aetiology. Priority should be given to further development and testing of promising treatment options for patients with CFS/ME. Classification of patients according to severity and symptom patterns, aiming to identify characteristics of patients that might predict differences in prognosis or expected effects of therapy, might be useful. Development of further case definitions of CFS/ME should be given low priority. Consistency in research can be achieved by application of diagnostic criteria which have been systematically evaluated and compared with other case definitions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KM had the original idea, and all five authors worked together to develop an appropriate theoretical framework and design. MSF developed the search, and all authors were involved in the selection process. LL and KGB extracted relevant data, KGB performed the statistical analysis and all authors were involved in the data interpretation. KM wrote the manuscript draft and revised the draft based on input from the other authors. All authors revised it critically for content and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are extracted from the cited primary studies.

References

- 1.Afari N, Buchwald D. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a review. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:221–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prins JB, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 2006;367:346–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White PD. What causes chronic fatigue syndrome? BMJ 2004;329:928–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komaroff AL, Geiger AM, Wormsely S. IgG subclass deficiencies in chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 1988;1:1288–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald D, Wener MH, Pearlman T, et al. Markers of inflammation and immune activation in chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome. J Rheumatol 1997;24:372–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorusso L, Mikhaylova SV, Capelli E, et al. Immunological aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 2009;8:287–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wensaas KA, Langeland N, Hanevik K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. Gut 2012;61:214–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komaroff AL. Chronic fatigue syndromes: relationship to chronic viral infections. J Virol Methods 1988;21:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fluge O, Bruland O, Risa K, et al. Benefit from B-lymphocyte depletion using the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab in chronic fatigue syndrome. A double-blind and placebo-controlled study. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e26358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr JR, Petty R, Burke B, et al. Gene expression subtypes in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J Infect Dis 2008;197:1171–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salit IE. Precipitating factors for the chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychiatr Res 1997;31:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, et al. Premorbid predictors of chronic fatigue. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:1267–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knoop H, Prins JB, Moss-Morris R, et al. The central role of cognitive processes in the perpetuation of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:489–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lange FP, Kalkman JS, Bleijenberg G, et al. Gray matter volume reduction in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuroimage 2005;26:777–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada T, Tanaka M, Kuratsune H, et al. Mechanisms underlying fatigue: a voxel-based morphometric study of chronic fatigue syndrome. BMC Neurol 2004;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyller VB, Godang K, Morkrid L, et al. Abnormal thermoregulatory responses in adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: relation to clinical symptoms. Pediatrics 2007;120:e129–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyller VB, Saul JP, Amlie JP, et al. Sympathetic predominance of cardiovascular regulation during mild orthostatic stress in adolescents with chronic fatigue. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2007;27:231–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker AJ, Wessely S, Cleare AJ. The neuroendocrinology of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Psychol Med 2001;31:1331–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van HB, Van Den Eede F, Luyten P. Does hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hypofunction in chronic fatigue syndrome reflect a ‘crash’ in the stress system? Med Hypotheses 2009;72:701–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes GP, Kaplan JE, Gantz NM, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition. Ann Intern Med 1988;108:387–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maes M, Twisk FNM, Johnson C. Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and chronic fatigue (CF) are distinguished accurately: results of supervised learning techniques applied on clinical and inflammatory data. Psychiatry Res 2012;200:754–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2003;11:7–115 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: international consensus criteria. J Intern Med 2011;270:327–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston S, Brenu EW, Staines DR, et al. The adoption of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis case definitions to assess prevalence: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol 2013;23:371–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. BMJ 2003;326:41–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reitsma JB, Rutjes AW, Khan KS, et al. A review of solutions for diagnostic accuracy studies with an imperfect or missing reference standard. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnston S, Brenu EW, Staines D, et al. The prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:105–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillman DA, Eltinge JL, Groves RM, et al. Survey nonresponse in design, data collection and analysis. In Groves RM, Kalton G, Rao JNK, Schwartz N, Skinner C. eds Survey nonresponse. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002:3–26 [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 29 Aug 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lumley T. rmeta: meta-analysis. R package version 2.16. 2012. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rmeta (accessed 6 Aug 2013).

- 33.Jason LA, Brown A, Clyne E, et al. Contrasting case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Eval Health Prof 2012;35:280–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osoba T, Pheby D, Gray S, et al. The development of an epidemiological definition for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2008;14:16–84 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones JF, Kohl KS, Ahmadipour N, et al. Fatigue: Case definition and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 2007;25:5685–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD, et al. Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3: 31–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dowsett EG, Ramsay AM, McCartney RA, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: a persistent enteroviral infection? Postgrad Med J 1990;66:1990–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komaroff AL, Fagioli LR, Geiger AM, et al. An examination of the working case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med 1996;100:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:953–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharpe MC, Archard LC, Banatvala JE, et al. A report—chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. J R Soc Med 1991;84:118–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jason LA, Corradi K, Torres-Harding S. Toward an empirical case definition of CFS. J Soc Serv Res 2007;34:43–54 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramsey MA. Myalgic encephalomyelitis and postviral fatigue states: the saga of royal free disease. 2nd edn London, UK: Gower, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ho-Yen DO. Patient management of post-viral fatigue syndrome. Br J Gen Pract 1990;40:37–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lloyd AR, Hickie I, Boughton CR, et al. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in an Australian population. Med J Aust 1990;153:522–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyde BM. The nightingale definition of myalgic encephalomyelitis (M.E.). Ottawa, Canada: The Nightingale Research Foundation, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Collaborating Center for Primary Care NICE clinical guideline 53. Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy): diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in adults and children. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jason LA, Evans M, Porter N, et al. The development of a revised Canadian myalgic encephalomyelitis chronic fatigue syndrome case definition. Am J Biochem Biotechnol 2010;6:120–35 [Google Scholar]

- 48.The National Task Force on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Report from the National Task Force on chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), post viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS), myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). Bristol: Westcare, The National Task Force on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartz AJ, Kuhn EM, Levine PH. Characteristics of fatigued persons associated with features of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 1998;4:71–97 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nacul LC, Lacerda EM, Pheby D, et al. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Med 2011;9:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pheby D, Lacerda E, Nacul L, et al. A disease register for ME/CFS: report of a pilot study. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jason LA, Torres-Harding SR, Jurgens A, et al. Comparing the Fukuda et al. criteria and the Canadian case definition for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2004;12:2004–52 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown AA, Jason LA, Evans MA, et al. Contrasting case definitions: the ME International Consensus Criteria vs. the Fukuda et al. CFS criteria. North Am J Psychol 2013;15:103–20 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, et al. The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1449–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindal E, Stefansson JG, Bergmann S. The prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Iceland—a national comparison by gender drawing on four different criteria. Nord J Psychiatry 2002;56:273–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bates DW, Schmitt W, Buchwald D, et al. Prevalence of fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in a primary care practice. Arch Intern Med 1993;153:2759–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawakami N, Iwata N, Fujihara S, et al. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in a community population in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med 1998;186:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lawrie SM, Pelosi AJ. Chronic fatigue syndrome in the community. Prevalence and associations. Br J Psychiatry 1995;166:793–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swanink CM, Vercoulen JH, Bleijenberg G, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a clinical and laboratory study with a well matched control group. J Intern Med 1995;237:499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011;377:823–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamilton WT, Gallagher AM, Thomas JM, et al. The prognosis of different fatigue diagnostic labels: a longitudinal survey. Fam Pract 2005;22:383–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chalder T, Power MJ, Wessely S. Chronic fatigue in the community: ‘a question of attribution’. Psychol Med 1996;26:791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reeves WC, Wagner D, Nisenbaum R, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a clinically empirical approach to its definition and study. BMC Med 2005;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reeves WC, Jones JF, Maloney E, et al. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia. Popul Health Metr 2007;5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jason LA, Najar N, Porter N, et al. Evaluating the Centers for Disease Control's empirical chronic fatigue syndrome case definition. J Disabil Policy Stud 2009;20:93–100 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Twisk FN, Maes M. A review on cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): CBT/GET is not only ineffective and not evidence-based, but also potentially harmful for many patients with ME/CFS. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2009;30:284–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mearin F, Lacy BE. Diagnostic criteria in IBS: useful or not? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:791–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pawlikowska T, Chalder T, Hirsch SR, et al. Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress. BMJ 1994;308:763–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brimacombe M, Helmer D, Natelson BH. Clinical differences exist between patients fulfilling the 1988 and 1994 case definitions of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychol Med S 2002;9: 309–14 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jason LA, Torres-Harding SR, Taylor RR, et al. A comparison of the 1988 and 1994 diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychol Med S 2001;8:337–43 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jason LA, Skendrovic B, Furst J, et al. Data mining: comparing the empiric CFS to the Canadian ME/CFS case definition. J Clin Psychol 2012;68:41–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jason LA, Helgerson J, Torres-Harding SR, et al. Variability in diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome may result in substantial differences in patterns of symptoms and disability. Eval Health Prof 2003;26:3–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wearden AJ, Dowrick C, Chew-Graham C, et al. Nurse led, home based self help treatment for patients in primary care with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stubhaug B, Lie SA, Ursin H, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy v. mirtazapine for chronic fatigue and neurasthenia: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:217–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bazelmans E, Vercoulen JHMM, Swanink CMA, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome and primary fibromyalgia syndrome as recognized by GPs. Fam Pract 1999;16:602–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Buchwald D, Umali P, Umali J, et al. Chronic fatigue and the chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence in a Pacific northwest health care system. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:15–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gunn WJ, Connell DB, Randall B. Epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: the Centers for Disease Control Study. Ciba Found Symp 1993;173:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Price RK, North CS, Wessely S, et al. Estimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome and associated symptoms in the community. Public Health Rep 1992;107:514–22 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Versluis RG, de Waal MW, Opmeer C, et al. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in 4 family practices in Leiden. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1997;141:1523–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bierl C, Nisenbaum R, Hoaglin DC, et al. Regional distribution of fatiguing illnesses in the United States: a pilot study. Popul Health Metrics 2004;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cho HJ, Menezes PR, Hotopf M, et al. Comparative epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome in Brazilian and British primary care: prevalence and recognition. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:117–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Evengård B, Jacks A, Pedersen NL, et al. The epidemiology of chronic fatigue in the Swedish Twin Registry. Psychol Med 2005;35:1317–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hamaguchi M, Kawahito Y, Takeda N, et al. Characteristics of chronic fatigue syndrome in a Japanese community population: chronic fatigue syndrome in Japan. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:895–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, et al. A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2129–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim CH, Shin HC, Won CW. Prevalence of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in Korea: community-based primary care study. J Korean Med Sci 2005;20:529–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Njoku MG, Jason LA, Torres-Harding SR. The prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Nigeria. J Health Psychol 2007;12:461–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reyes M, Nisenbaum R, Hoaglin DC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Wichita, Kansas. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1530–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steele L, Dobbins JG, Fukuda K, et al. The epidemiology of chronic fatigue in San Francisco. Am J Med 1998;105:83S–90S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.van't Leven M, Zielhuis GA, van der Meer JW, et al. Fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome-like complaints in the general population. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:251–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vincent A, Brimmer DJ, Whipple MO, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and classification of chronic fatigue syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, as estimated using the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1145–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yiu YM, Qiu MY. A preliminary epidemiological study and discussion on traditional Chinese medicine pathogenesis of chronic fatigue syndrome in Hong Kong. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao/J Chin Integr Med 2005;3:359–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ho-Yen DO, McNamara I. General practitioners’ experience of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Gen Pract 1991;41:324–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.