Abstract

Objective

To describe the use of antibiotics for urinary tract infection (UTI) before and after surgery for urinary incontinence (UI); and for those with use of antibiotics before surgery, to estimate the risk of treatment for a postoperative UTI, relative to those without use of antibiotics before surgery.

Design

A historical population-based cohort study.

Setting

Denmark.

Participants

Women (age ≥18 years) with a primary surgical procedure for UI from the county of Funen and the Region of Southern Denmark from 1996 throughout 2010. Data on redeemed prescriptions of antibiotics ±365 days from the date of surgery were extracted from a prescription database.

Main outcome measures

Use of antibiotics for UTI in relation to UI surgery, and the risk of being a postoperative user of antibiotics for UTI among preoperative users.

Results

A total of 2151 women had a primary surgical procedure for UI; of these 496 (23.1%) were preoperative users of antibiotics for UTI. Among preoperative users, 129 (26%) and 215 (43.3%) also redeemed prescriptions of antibiotics for UTI within 0–60 and 61–365 days after surgery, respectively. Among preoperative non-users, 182 (11.0%) and 235 (14.2%) redeemed prescriptions within 0–60 and 61–365 days after surgery, respectively. Presurgery exposure to antibiotics for UTI was a strong risk factor for postoperative treatment for UTI, both within 0–60 days (adjusted OR, aOR=2.6 (95% CI 2.0 to 3.5)) and within 61–365 days (aOR=4.5 (95% CI 3.5 to 5.7)).

Conclusions

1 in 4 women undergoing surgery for UI was treated for UTI before surgery, and half of them had a continuing tendency to UTIs after surgery. Use of antibiotics for UTI before surgery was a strong risk factor for antibiotic use after surgery. In women not using antibiotics for UTI before surgery only a minor proportion initiated use after surgery.

Keywords: Surgery, Antibiotics, Clinical epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A population-based study.

2151 included women.

High quality of data sources and complete information in the follow-up period for all included women.

Adjustment for several factors: age, procedure type, preoperative oestrogen use, comorbidity, educational level and personal annual income.

Redeemed prescriptions were used as a proxy for drug use.

No data on symptomatology, catheter usage, preoperative antibiotics or urine culture.

Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common problem in women, and 40% of women have UTI during their life-time—of these, 27% have recurrent UTI within 12 months.1 There are several risk factors for UTI and recurrent UTI; for example, high age, urogenital atrophy and urinary incontinence (UI).2 3 UI is associated with UTI,2 4 and UTI might be regarded as a comorbid condition in women with UI due to several factors including poor perineal hygiene.5 Thus, it is not surprising that UTI is seen in women with UI, but no studies have so far examined the burden of UTI in women undergoing surgery for UI in a population-based setting.

It is also well known that UTI is common after UI surgery. Risk factors of postoperative UTI include previous recurrent UTI, postoperative catheterisation, positive urine cultures at day of surgery and preoperative postvoid residual.6–9 UTI after UI surgery might occur among 6–38% of the women—depending on diagnostic methods and criteria.8 10–16 and surgery-related infections occur within 2 months.17 Thus, while some knowledge of UTI exists in the short-term perspective after UI surgery, there is only little evidence on the frequency of UTI in a more long-term perspective after UI surgery.8

The purpose of this study was to examine the use of antibiotics for UTI before and after surgery for UI, and among women using antibiotics for UTI before surgery to estimate the risk of postoperative use in a short-term and long-term perspective. This topic is clinically highly relevant in the counselling of women prior to surgery for UI: What can they expect of postoperative complications? Can preoperative drug users expect to continue drug use after surgery?

Materials and methods

Study population and settings

Women were included in the study if they had a primary surgical procedure for UI within the period of 1 January 1996 through 31 December 2010. Data on performed procedures were retrieved from the Danish National Patient Registry (NPR)18 according to codes listed in online supplementary appendix 1. The surgical procedures were performed in one of four hospitals in the county of Funen, Denmark, between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2006 or for the period 2007 through 2010 in 1 of 13 hospitals in the new Region of Southern Denmark (including Funen). The extension of the area was due to a change in the organisation of the healthcare system in 2007, including a structural change from 14 counties to 5 regions. Women with concomitant or prior surgery for pelvic organ prolapse were included. Women younger than 18 years were excluded.

Data sources

Data for this study were retrieved from three Danish registers: the NPR, Odense University Pharmacoepidemiologic Database (OPED), the Statistics Denmark. All Danish citizens are assigned a unique Civil Registration Number (CRN), which enables individual-level linkage across registries.19

The NPR contains data on discharges from public hospitals in Denmark, and the completeness of recordings has been estimated to be 99.4%.20 Information available in the registry pertain to the CRN, the dates of admission, dates of discharge and discharge diagnoses, classified according to the International Classification of Diseases-8 (ICD-8) (1977–1993) and ICD-10 (1994 and onward)21 22 as well as codes from the Danish classification system of surgical procedures.23

Information on relevant drugs (antibiotics and oestrogens) was retrieved from the OPED for the period 1995 to 2011 for the entire study population.

The OPED is pharmacy-based and captures all reimbursed prescriptions, and contains person-identifiable data with complete coverage on all computerised prescription reimbursements from the county of Funen (population 2006: 479 000) from 1990 and from January 2007 onwards extended to the whole Region of Southern Denmark (population 1.2 million). The age and gender distribution of this population are very similar to that of the Danish population as a whole (2006: 5.4 million), and the prescribing of drugs is very similar to the national average.24

Prescription reimbursements are given independent of patient income to all legal inhabitants of Denmark as a part of the National Health Service. Each record includes the CRN, date of purchase, a full account of what have been dispensed, including the brand name and the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification code. Information not included in the prescription database is drugs sold over the counter or drugs not reimbursed by the county authority (mainly oral contraceptives, sedatives and hypnotics). Data on highest attained educational level and annual income were retrieved from the Danish Integrated Database for Labour Market Research at Statistics Denmark, a database with annually updated socioeconomic data for each Danish citizen, mainly supplied by tax authorities, educational institutions and employment services.25

Antibiotics under study

Included drugs were antibiotics traditionally used in Denmark exclusively or predominantly for the treatment of UTI (sulphamethizole (ATC J01EB02), pivmecillinam (ATC J01CA08), nitrofurantoin (ATC J01XE01), trimethoprim (ATC J01EA01), as well as mecillinam (ATC J01CA11))26 27 and with a duration of 3–5 days. The indications for the prescribed drugs are not registered in the OPED; therefore, pivampicillin and amoxicillin were not included—as these antibiotics are also commonly used in treatment of upper respiratory tract infections. Likewise, broader spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporins and quinolones were not included, as they are not commonly used for UTIs in Denmark.

Exposed and unexposed cohorts

Exposed cohort: All women ≥18 years undergoing a primary surgical procedure for UI between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2010 in the county of Funen/Region of Southern Denmark, and having redeemed one or more prescriptions on antibiotics within 365 days preceding the date of surgery (index date).

Unexposed cohort: All women ≥18 years undergoing a primary surgical procedure for UI between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2010 in the county of Funen/Region of Southern Denmark without having redeemed similar prescriptions within the same time frame.

Outcome data

For both exposed and unexposed women, the outcome was use of antibiotics for UTI, defined as having redeemed at least one prescription for these antibiotics within (1) 60 days after the index date (short-term postoperative users) and (2) 61–365 days after the index date (long-term postoperative users). These outcomes were not mutually exclusive, that is, a woman might be classified as a short-term and long-term user, postoperatively.

Covariates

The use of antibiotics might be affected by age, type of surgery, use of oestrogen, comorbidity, calendar time and the individuals’ ability to pay for the medicine might be affected by educational level and annual income. Therefore, these variables were included in the analysis as potential confounders.

Type of procedures

The types of UI surgery were divided into four groups according to the surgical procedure code: (1) mid-urethral sling procedures with transobturator route (toMUS), (2) mid-urethral sling procedures with retropubic route (rpMUS), (3) bulking procedures and (4) other types of UI surgeries.

Oestrogen

Use of oestrogens (ATC G03C) was included in the analyses as a confounder.

To adjust for preoperative oestrogen use, preoperative users of oestrogens were defined as women who had redeemed at least one prescription for oestrogens within 365 days preceding the date of surgery and nonusers were defined as those who had no preoperative oestrogen use during the same period. The local and systemic oestrogens were included.

Comorbidity

The comorbidity was classified according to the validated, well-known and widely used Charlson comorbidity index (CCI),28–31 which assigns different weights (1, 2, 3 and 6) to 20 different disease categories specified by medical condition and severity (eg, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic pulmonary, renal, liver and connective tissue diseases). The CCI was computed based on each woman's complete hospital discharge history from the NPR since 1977. A categorised version of the CCI score values was used: 0 (low), 1–2 (medium) and 3+ (high).32

Education and income

Information on educational level and annual income for each woman was retrieved as a measure of socioeconomic status. Educational level was categorised according to the highest attained educational level in the year of surgery: ‘Basic’ (basic school/high school education: 7–12 years of primary, secondary and grammar school education), ‘Secondary’ (vocational education, 10–12 years of education) and ‘Higher’ (a university degree or an examination in another higher institution requiring an average total of 13 years or more).28

On the basis of quartiles of annual income for each woman in the year of her surgery, we categorised women in low (1st quartile), medium (2nd and 3rd quartile) and high income (4th quartile).

Statistical analysis

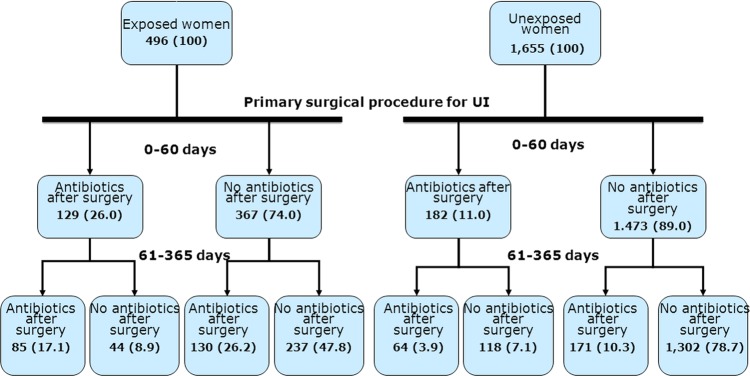

The use of antibiotics for UTI within the first 365 days after surgery for exposed and unexposed cohorts was illustrated in a flow chart. We also constructed contingency tables for the main study variables, and computed ORs, with 95% CIs.

To analyse the significance of preoperative antibiotic use as risk factor of postoperative use (within 60 days and within 61–365 days after surgery), adjusted ORs were estimated by means of multivariate logistic regression models.

Adjustment was made for age (18–39, 40–59 and ≥60 years (reference)), type of procedures (toMUS (reference), rpMUS, bulking, others), education (basic (reference), secondary, higher), annual income (low (reference), middle, high), comorbidity (CCI 0 (reference), CCI 1–2, CCI 3+), calendar year (1996–2006, 2007–2008 (reference), 2009–2010) and use of oestrogen within 365 days preceding the date of surgery (no (reference), yes).

Stratified analyses were performed according to the use of oestrogens before surgery to examine the association between the use of antibiotics for UTI in oestrogen users versus oestrogen non-users.

All analyses were performed using Stata Release V.12.0.

Results

A total of 2151 women had a primary surgical procedure for UI between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2010; 2073 had a solitary UI surgery, and 78 had concomitant surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

Of the 2151 women, 1655 (76.9%) women did not use antibiotics for UTI within 365 days preceding the date of surgery, while 496 (23.1%) did, and the majority (376/496=75.8%) redeemed ≤2 prescriptions preoperatively and only a minority (42/496=8%) redeemed more than five or more prescriptions. The use of antibiotics for UTI within 365 days after surgery is detailed for the exposed and unexposed cohorts in figure 1. The most commonly used antibiotics both preoperatively and postoperatively were sulphamethizol and pivmecillinam.

Figure 1.

Women (N=2151) with primary surgery for urinary incontinence (UI) and their use of antibiotics for urinary tract infection before and after surgery for UI. Exposed women had redeemed one or more prescriptions of antibiotics within 365 days preceding the date of surgery. Unexposed women had not redeemed prescriptions of antibiotics within 365 days preceding the date of surgery.

Women having redeemed prescriptions for antibiotics for UTI before surgery (exposed)

Of the 496 women with prior use of antibiotics for UTI, 129 (26%) redeemed a prescription for antibiotics for UTI within 0–60 days after surgery, and of these, 85 (65.9%) also within 61–365 days after surgery (figure 1). A total of 215 (43.3%) continued to redeem prescriptions for antibiotics within 61–365 days (figure 1).

Women with no usage of antibiotics for UTI before surgery (unexposed)

Of the 1655 women who did not redeem prescription before surgery, 182 (11%) women had a short-term use of antibiotics for UTI after surgery; and of these, 64 women were also long-term users (figure 1). Among unexposed without short-term postoperative use of antibiotics, 171 (10.3%) became long-term postoperative users (figure 1). The total number of women with long-term antibiotic use was 235 (14.2%).

Comparison of exposed and unexposed cohorts

Baseline characteristics of exposed and unexposed women are presented in table 1. The most commonly used procedure was to MUS accounting for approximately half of the procedures performed in both the exposed and the unexposed group. The most commonly prescribed drugs prior to surgery were sulphamethizol and pivmecillinam. Compared with unexposed women, exposed women tended to be older, to be more frequent oestrogen users and to have higher comorbidity indices. There was no difference in educational level or personal annual income.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all included women (N=2151) having a primary surgical procedure for UI in Denmark, 1996–2010

| Exposed* n=496 |

Unexposed† n=1655 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (±SD), years (at time of first UI surgery) | 60.2 (±13.2) | 54.2 (±12.4) |

| Age groups, n (%) | ||

| 18–39 | 30 (6.1) | 182 (11.0) |

| 40–59 | 196 (39.5) | 911 (55.1) |

| 60− | 270 (54.4) | 562 (33.9) |

| Procedures, n (%) | ||

| rpMUS | 140 (28.2) | 535 (32.3) |

| toMUS | 222 (44.8) | 750 (45.3) |

| Bulking | 110 (22.2) | 250 (15.1) |

| Others | 24 (4.8) | 120 (7.3) |

| Concomitant prolapse surgery, n (%) | 12 (2.4) | 66 (4.0) |

| Antibiotics before surgery, n (%)‡ | ||

| Sulfamethizol—J01EB02 | 299 (60.3) | – |

| Pivmecillinam—J01CA08 | 288 (58.1) | – |

| Nitrofurantoin—J01XE01 | 65 (13.1) | – |

| Trimethoprim—J01EA01 | 45 (9.1) | – |

| Mecillinam—J01CA11 | 0 (0) | – |

| Oestrogen users, n (%)§ | ||

| No | 211 (42.5) | 997 (60.2) |

| Yes | 285 (57.5) | 658 (39.8) |

| Comorbidity (CCI), n (%) | ||

| 0 | 298 (60.1) | 1214 (73.4) |

| 1–2 | 139 (28.0) | 381 (23.0) |

| 3+ | 59 (11.9) | 60 (3.6) |

| Educational level, n (%)¶ | ||

| Basic | 229 (47.4) | 688 (42.3) |

| Secondary | 170 (35.2) | 600 (36.8) |

| Higher | 84 (17.4) | 340 (20.9) |

| Annual income, n (%) | ||

| Low (1st quartile) | 152 (30.7) | 385 (23.3) |

| Middle (2nd–3rd quartile) | 252 (50.8) | 825 (49.9) |

| High (4th quartile) | 92 (18.5) | 445 (26.9) |

| Year of surgery n (%) | ||

| 1996–2006 | 106 (21.4) | 353 (21.3) |

| 2007–2008 | 186 (37.5) | 605 (36.6) |

| 2009–2010 | 204 (41.1) | 697 (42.1) |

*Exposed women had redeemed one or more prescriptions of antibiotics within 365 days preceding the date of surgery. †Unexposed women had not redeemed prescriptions of antibiotics within 365 days preceding the date of surgery.

‡Does not sum up to 100%. Some women redeemed more than one type of the drugs during the time period.

§Women with at least one redeemed prescription of oestrogen within 365 days preceding the date of surgery.

¶Unknown highest attained educational level: 40 women.

CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; rpMUS, retropubic mid-urethral sling, toMUS, trans-obturator mid-urethral sling.

The unadjusted OR of a prior antibiotic user being a postoperative short-term and long-term user was 2.8 (95% CI 2.2 to 3.7) and 4.6 (95% CI 3.7 to 5.8), respectively. The adjusted OR of being short-term and long-term user of antibiotics for UTI after surgery was 2.6 (95% CI 2.0 to 3.5) and 4.5 (95% CI 3.5 to 5.7), respectively (table 2). Thus, adjustment for confounders did virtually not change the relative risk estimates. The details from logistic regression models are presented in table 2 showing the impact of each prognostic factor included. Regarding short-term use, the strongest risk factors were procedure types (rpMUS/others), high comorbidity index and preoperative antibiotic use. Preoperative use of antibiotics for UTI was the strongest risk factor of long-term postoperative use.

Table 2.

Risk factors of postoperative use of antibiotics

| Postoperative non-use | Postoperative short-term use |

Postoperative non-use | Postoperative long-term use |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | OR (95% CI) | Number | Number | OR (95% CI) | |

| Preoperative use | ||||||

| No | 1473 | 182 | Reference | 1420 | 235 | Reference |

| Yes | 367 | 129 | 2.6 (2.0 to 3.5) | 281 | 215 | 4.5 (3.5 to 5.7) |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–39 | 185 | 27 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | 163 | 49 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.3) |

| 40–59 | 981 | 126 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.9) | 931 | 176 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

| 60− | 674 | 158 | Reference | 607 | 225 | Reference |

| Procedure | ||||||

| rpMUS | 568 | 107 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.7) | 529 | 146 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) |

| toMUS | 849 | 123 | Reference | 782 | 190 | Reference |

| Bulking | 315 | 45 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | 278 | 82 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Others | 108 | 36 | 3.1 (1.6 to 5.9) | 112 | 32 | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.8) |

| Preoperative use of oestrogen* | ||||||

| No | 1059 | 149 | Reference | 992 | 216 | Reference |

| Yes | 781 | 162 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.6) | 709 | 234 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Comorbidity (CCI) | ||||||

| 0 | 1328 | 184 | Reference | 1241 | 271 | Reference |

| 1–2 | 425 | 95 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | 384 | 136 | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) |

| 3+ | 87 | 32 | 3.1 (1.6 to 5.9) | 76 | 43 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.4) |

| Educational level† | ||||||

| Basic | 775 | 142 | Reference | 702 | 215 | Reference |

| Secondary | 665 | 105 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 623 | 147 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Higher | 362 | 62 | 1.3 (0.9 to 2.0) | 342 | 82 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Annual income | ||||||

| Low | 434 | 103 | Reference | 404 | 133 | Reference |

| Middle | 930 | 147 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | 847 | 230 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

| High | 476 | 61 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | 450 | 87 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Year of surgery | ||||||

| 1996–2006 | 363 | 96 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) | 352 | 107 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| 2007–2008 | 692 | 99 | Reference | 628 | 163 | reference |

| 2009–2010 | 785 | 116 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) | 721 | 180 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) |

Results from multivariate logistic regression models on (1) short-term (0–60 days after surgery) and (2) long-term (61–356 days after surgery).

*Women with at least one redeemed prescription of oestrogen within 365 days preceding the date of surgery.

†Unknown highest attained educational level: 40 women.

CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; Post op, postoperative; rpMUS, retropubic mid-urethral sling; toMUS, trans-obturator mid-urethral sling.

Stratified analyses according to the use of oestrogens before surgery showed that among users of oestrogen, the adjusted OR for short-term and long-term use of antibiotics for UTI after surgery increased to 3.3 (95% CI 2.3 to 4.8) and 5.2 (95% CI 3.7 to 7.3), respectively, table 3.

Table 3.

Stratified analyses according to use of oestrogen before surgery for UI to examine the association between preoperative use of antibiotics for urinary tract infection and postoperative use

| Preoperative oestrogen n | Preoperative antibiotics n |

Crude OR (95% CI) Short-term |

Adjusted OR* (95% CI) Short-term |

Crude OR (95% CI) Long-term |

Adjusted OR* (95% CI) Long-term |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes 943 | Yes No |

285 658 |

3.5 (2.5 to 5.0) | 3.3 (2.3 to 4.8) | 5.2 (3.8 to 7.2) | 5.2 (3.7 to 7.3) |

| No 1208 | Yes No |

211 997 |

2.0 (1.3 to 2.9) | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.0) | 3.8 (2.7 to 5.2) | 3.7 (2.6 to 5.3) |

*Adjusted for age, procedure type, comorbidity, educational level, annual income and calendar year of surgery.

Discussion

Among 2151 women undergoing surgery for UI, nearly one-fourth had redeemed at least one prescription of antibiotics for UTI preoperatively, and among preoperative users nearly half of the women also redeemed prescriptions of antibiotics for UTI within 61–365 days after surgery. Among preoperative users of antibiotics we found a 2–3-fold increased risk of short-term use of antibiotics for UTI after surgery, and a 4–5-fold increased risk of being long-term user. In women not using antibiotics for UTI before surgery only a minor proportion initiated use of antibiotics after surgery.

To ensure that our results were not influenced by effect modification of oestrogen use we stratified our analyses for preoperative use of oestrogen. In both strata we found an increased risk of postoperative antibiotic use for the exposed women. The risk estimates for short-term and long-term use were, however, higher among women using oestrogen preoperatively compared with women without prior oestrogen use.

The proportion of women with concomitant surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in our cohort of women with UI surgery was low, and this was as expected given the current practice in Scandinavia with a conservative approach of addressing the predominant problem of either pelvic organ prolapse or UI in sequential surgery.33 Thus, our results were not influenced by a mixed cohort with both UI surgery and pelvic organ prolapse surgery.

Our study has several strengths: (1) it is population-based in the sense that this study covers all the relevant surgeries in a well-defined geographic area in Denmark, (2) the source of procedure codes in the NPR has high coverage and validity—the NPR records 99.4% of all discharges from hospitals in Denmark, and the procedures in the NRP have been validated showing a high quality of the data with positive predictive values of 94–100%,34–36 (3) the access to high-quality data on prescriptions from the OPED that are representative for the Danish population,24 (4) information on several confounders such as comorbidity and socioeconomic status, (5) complete information on the follow-up period for all included women, (6) outcome data on postoperative antibiotic prescriptions are recorded independently of prior antibiotic use, thus preventing differential misclassification of the outcome, (7) the antibiotics included in this study are UTI specific and are drugs of choice in Denmark for treating UTI and finally (8) the surgical procedures included have no other indications than UI, which strongly limits the number of alternative interpretations of our findings. Furthermore, the exclusion of antibiotics with other indications than UTI may even have led to an underestimation of the risk of UTI.

There are possible limitations to our study. We have no information on perioperative use of antibiotic, antibiotic given while the patient was still hospitalised, or results of urine culture. A redeemed prescription of antibiotics for UTI does not necessarily equal a UTI, and urine culture is not always performed prior to a prescription. Thus, empiric therapy is possible. To prevent UTI and other postoperative infections a perioperative single-dose of intravenous antibiotic is often used in Denmark.37 However, perioperative antibiotic use is unlikely to be much different between exposed and unexposed cohorts and will thus not bias our relative risk estimates. In the short-term perspective after surgery we had no knowledge of postoperative catheter usage which is a limitation, especially since postoperative UTI is associated with catheter usage in the postoperative period,38 39 but again we have no reasons to believe that use of catheters differed among exposed and unexposed cohorts. We were not able to control for all potential confounders such as body mass index, parity, intraoperative bladder perforation or precise menopausal status, but the importance of these factors for the association examined in this study is not clear. We had no data on patient symptomatology, that is, whether stress UI, urgency UI, mixed UI or overactive bladder syndrome were predominant, or on urodynamic study, and it could have been interesting to further examine the users of UTI antibiotics (both before and after surgery) according to the type of UI symptomatology.

It is surprising that among women using antibiotics for UTIs before UI surgery, half of them have a continuing tendency to use these antibiotics after surgery. This is not explained by recurrent UI surgery in the study period of 1 year after surgery as only approximately 5% of women experienced a new surgery in our population. Possible explanations for the continuing tendency to UTI could be a genetic predisposition for UTI, an anatomic predisposition for UTI, or an increased awareness of UTI for both the women and their doctor.

On the basis of the flow chart in our study, we observed a tendency to continuing UTI among women with preoperative antibiotic use in short-term and long-term, postoperatively. To our knowledge, this is the largest, and only population-based, study examining the use of antibiotics for UTI in relation to surgery for UI and addressing the risk of short-term and long-term postoperative use of antibiotics for UTI among women with preoperative UTI. In addition, our study provides knowledge about which other factors than preoperative antibiotic were important for postoperative antibiotic use for UTI. We found that for short-term use procedure type (rpMUS, others), and high comorbidity were risk factors and for long-term use high comorbidity was a risk factor. Our study also showed that educational level and personal income did not seem to influence the risk of postoperative antibiotic use.

In Denmark, dipstick urine test is a part of the preoperative examination, and surgeons might feel encouraged to treat the women with antibiotics prior to surgery based on dipstick urine test without symptoms or urine culture in an attempt to try to minimise the risk of postoperative UTI.

According to the Danish Programme for the surveillance of antimicrobial consumption and resistance in bacteria from animals, food and humans, the resistance, especially in bacteria other than Escherichia coli, has increased during the last years. E coli is the most frequent cause of UTIs both in community-acquired and hospital-acquired UTIs.

Our study calls for further studies within this area—studies examining UTI before and after surgery according to different types of UI (stress UI, urgency UI, mixed UI), UTI in relation to surgery in especially postmenopausal women, issues regarding recurrent UTI and UI surgery, and if prophylactic antibiotic use (perioperative intravenous/prolonged oral antibiotics) could reduce the risk of postoperative UTI after UI surgery in a short-term and long-term perspective. Furthermore, it would be interesting to assess the use of similar antibiotics in the background population of women to examine whether there is an increased antibiotic burden associated with surgery for UI.

In conclusion, we found that one in four women undergoing surgery for UI was treated for UTI before surgery, and half of these women continued the tendency of UTI after surgery. In women not using antibiotics for UTI before surgery only a minor proportion initiated use of antibiotics for UTI after surgery. The strongest risk factor of postoperative use of antibiotics for UTI was the use of these antibiotics before surgery.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have drafted the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version to be published. All authors are responsible for the study concept and design, and participated in the interpretation of data. RG is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by (1) Nordic Urogynaecology Association (NUGA) Research Grant. (2) A P Møller and Chastine Mc-Kinney Møller Foundation for General Purposes. (3) Center for Clinical Epidemiology, Odense University Hospital and (4) Region of Southern Denmark.

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (no. 2009-41-3564). According to Danish law, ethical review board approval or patient consent are not required for register-based studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: According to the Danish Data Protection Agency, we are not allowed to share our data from the Danish National Patient Registry. This would require a special approval from both the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Statens Serum Institut who provides the data from the Danish National Patient Registry.

References

- 1.Foxman B. Recurring urinary tract infection: incidence and risk factors. Am J Public Health 1990;80:331–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athanasiou S, Anstaklis A, Betsi GI, et al. Clinical and urodynamic parameters associated with history of urinary tract infections in women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:1130–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu KK, Boyko EJ, Scholes D, et al. Risk factors for urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:989–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raz R, Gennesin Y, Wasser J, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodhare TN, Valsangkar S, Bele SD. An epidemiological study of urinary incontinence and its impact on quality of life among women aged 35 years and above in a rural area. Indian J Urol 2010;26:353–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fok CS, McKinley K, Mueller ER, et al. Day of surgery urine cultures identify urogynecologic patients at increased risk for postoperative urinary tract infection. J Urol 2013;189:1721–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutkin G, Alperin M, Meyn L, et al. Symptomatic urinary tract infections after surgery for prolapse and/or incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21:955–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Chai TC, et al. Risk factors for urinary tract infection following incontinence surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:1255–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingber MS, Vasavada SP, Firoozi F, et al. Incidence of perioperative urinary tract infection after single-dose antibiotic therapy for midurethal slings. Urology 2010;76:830–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson D, Higgins E, Bracken J, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary tract infection after midurethral sling: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2013;19:137–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anger J, Litwin M, Wang Q, et al. Complications of sling surgery among female Medicare beneficiaries. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:707–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanford EJ, Paraiso MFR. A comprehensive review of suburethral sling procedure complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 1999;15:132–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaSala CA, Schimpf MO, Udoh E, et al. Outcome of tension-free vaginal tape procedure when complicated by intraoperative cystotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:1857–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugsley H, Barbrook C, Mayne CJ, et al. Morbidity of incontinence surgery in women over 70 years old: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG 2005;112:786–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ 2002;325:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamussino K, Hanzal E, Kolle D, et al. Tension-free vaginal tape operation: results of the Austrian registry. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:732–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Terminology and Classification of the Complications Related Directly to the Insertion of Prostheses (Meshes, Implants, Tapes) and Grafts in Female P. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen T, Madsen M, Jørgensen J, et al. The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 1999;46:262–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death (ICD-8). Geneva, Switzerland, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization Internatinal Classification of Diseases—10th revision (ICD-10) [Internet]. 2013. http://www.who.int/classifications/ics/en/

- 23.Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures, version 1.15. 2010. no. 93

- 24.Gaist D, Sørensen H, Hallas J. The Danish Prescription Registers. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:445–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:95–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjerrum L, Grindsted P. How to treat uncomplicated cystitis? Ugeskr Laeger 2000;162:197–8 [Danish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjerrum L, Dessau R, Hallas J. Treatment failures after antibiotic therapy of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. A prescription study. Scand J Primary Health Care 2002;20:97–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Engholm G, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from lung cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1989–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson M, Pompei P, Ales K, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneeweiss S, Maclure M. Use of comorbidity scores for control of confounding in studies using administrative databases. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:891–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomsen R, Riis A, Christensen S, et al. Diabetes and 30-day mortality from a Danish population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2006;29:805–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svenningsen R, Borstad E, Spydslaug AE, et al. Occult incontinence as predictor for postoperative stress urinary incontinence following pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:843–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen T, Madsen M, Loft A. Validity of surgical information from the Danish National Patient Registry with special attention to the analysis of regional variations in hysterectomy rates. Ugeskr Laeger 1987;149:2420–2 [Danish]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosbech J, Jørgensen J, Madsen M, et al. The national patient registry. Evaluation of data quality. Ugeskr Laeger 1995;157: 3741–5 [Danish]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ottesen M. Validity of the registration and reporting of vaginal prolapse surgery. Ugeskr Laeger 2009;171:404–8 [Danish]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guldberg R, Brostrøm S, Hansen JK, et al. The Danish Urogynaecological Database: establishment, completeness and validity. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:983–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wald H, Ma A, Bratzler D, et al. Indwelling urinary catheter use in the postoperative period. Arch Sur 2008;143:551–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Platt R, Polk B, Murdock B, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial urinary tract infection. Am J of Epidemiol 1986;124:977–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.