Abstract

Objectives

To compare the validity of parent-reported height, weight and body mass index (BMI) values of children (aged 4–10 years), when measured at home by means of newly developed instruction leaflets in comparison with simple estimated parental reports.

Design

Randomised controlled trial with control and intervention group using simple randomisation.

Setting

Belgian children and their parents recruited via schools (multistage cluster sampling design).

Participants

164 Belgian children (53% male; participation rate 62%).

Intervention

Parents completed a questionnaire including questions about the height and weight of their child. Parents in the intervention group received instruction leaflets to measure their child's weight and height. Classes were randomly allocated to the intervention and control groups. Nurses measured height and weight following standardised procedures up to 2 weeks after parental reports.

Outcome measures

Weight, height and BMI category of the child were derived from the index measurements and the parental reports.

Results

Mean parent-reported weight was slightly more underestimated in the intervention group than in the control group relative to the index weights. However, for all three parameters (weight, height and BMI), correlations between parental reports and nurse measurements were higher in the intervention group. Sensitivity for underweight and overweight/obesity was respectively, 75% and 60% in the intervention group, and 67% and 43% in the control group. Weighed κ for classifying children in the correct BMI category was 0.30 in the control group and was 0.51 in the intervention group.

Conclusions

Although mean parent-reported weight was slightly more underestimated in the intervention than in the control group, correlations were higher and there was considerably less misclassification into valid BMI categories for the intervention group. This pattern suggests that most of the parental deviations from the index measurements were probably due to random errors of measurement and that diagnostic measures could improve by encouraging parents to measure their children's weight and height at home by means of instruction leaflets.

Keywords: Nutrition & Dietetics, Paediatrics, Preventive Medicine, Public Health, Statistics & Research Methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study investigating the validity of instruction folders for parents to accurately measure their child's weight and height at home by comparison with simple estimated parental reports.

An important strength of this study is the high level of standardisation in the reference measurements performed by the experienced and trained Centrum voor Leerlingenbegeleiding (CLB) nurses, and the inclusion of parent-measured and parent-estimated child dimensions.

The criterion examination by the CLB nurses was performed about 2 weeks after completion of the questionnaire. As there might be up to 2 weeks between the two assessments, the true weight and height might change during this period. However, large changes, which might influence the present results, are unlikely to have occurred during that period.

Introduction

With a growing interest in childhood obesity as a factor in child morbidity and adult diseases,1 valid measures of childhood weight and height are of interest to many researchers. Owing to logistical difficulties and financial costs involved in directly measuring weight and height of children in a survey, such data are often proxy reported (eg, by parents).2–6 Previous studies focusing on the validity of parent-reported weight and height values in children have shown fairly poor accuracy of parentally reported values for classifying children into body mass index (BMI) categories of underweight, overweight and obesity status.7–9 From a recent review of the literature, Himes10 concluded that proxy measures for directly measured BMI, such as self-reports or parental reports of height and weight, are much less preferred and should only be used with caution and awareness of the limitations, biases and uncertainties of these measures. Nevertheless, because direct measurements of weight and height are costly and time consuming, large surveys in childhood populations are likely to continue to use parent-reported values. A practical solution to improve the validity of these parent reports might be to ask parents to measure the weight and height of their children at home and to provide the parents with instructions concerning how to measure their child in an accurate way. A previous study demonstrated relatively better accuracy when parents reported that they had measured their child's weight and height at home (using unspecified methods) compared with parents who estimated their child's body size without taking measurements.11 To date, however, we are unaware of any studies evaluating the usefulness and validity of instruction leaflets for parents concerning how to measure the weight and height of their child at home.

The aim of the present study was to develop and validate user-friendly instruction leaflets for parents to measure their child at home using their own measurement instruments (scale and ruler). Furthermore, we compared the validity of parent-reported weight and height values of their child after being measured at home using the newly developed instruction leaflets in comparison with parents who did not receive the instruction leaflets. We also compared the accuracy of the parent reports for classifying children into BMI categories, using international BMI cut-off values for underweight, overweight and obesity.

Methods

Study population and design

Participants were residents in the region of Ghent, a medium sized city in Belgium. A sample of 4–10-year-old children was recruited using a multistage cluster sampling technique. First, three school committees were randomly selected in the region of Ghent and they all agreed to participate (a school committee manages/governs one or more schools). In total, these three school committees included five different school residences/locations. All 17 (pre)school classes in these five schools were selected as final cluster units. All the children from these 17 selected classes were invited to participate (only the eldest child in case of brothers/sisters) between September 2011 and July 2012. A randomised controlled trial design was used to allocate classes randomly to either receive instruction leaflets for parents describing how to measure their child's weight and height accurately at home (intervention group) or not to receive any instruction leaflet (control group). Simple randomisation was used to allocate the classes to the intervention or control group, by means of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows V.20, using the procedure ‘select random sample of cases’. Eight classes were randomly allocated to the intervention group and nine classes to the control group.

Instruction folder/leaflet for measuring children's weight and height at home

Instruction folders illustrating and describing how to measure children's weight and height at home were developed in close collaboration with paediatricians and experts in anthropometric measurements. A preliminary draft of these leaflets was pilot tested in a convenience sample of 28 children and was modified afterwards considering the feedback from the parents who used the leaflets. The final instruction folders are available in online supplementary annexes 1 and 2. Written informed consent from the child's parent and the staff member performing the measurements in the attached instruction folders was obtained prior to photography.

Questionnaire and self-reported anthropometry

No protocol or instructions were provided for measuring the child at home in the control group. Information about the child (eg, gender and age) and his or her parents (eg, age, gender and parental education levels) was obtained via a self-administered parental questionnaire in both the intervention and control group. Parents were also asked to report the weight and height of their child in this questionnaire. In addition, they were asked to report if they actually measured their child's weight and height prior to reporting, or if they estimated the values without their own measurement. Furthermore, they were asked to report the time of the day when the measurements were performed as weight tends to increase, while height tends to decrease during the day.12–14 The parents in the intervention group were asked if they had used the instruction folders (online supplementary annexes 1 and 2) during the measurements or not.

Anthropometric measurements

This study was conducted in collaboration with Centers for Pupils Counselling (‘Centrum voor Leerlingenbegeleiding’ (CLB) in Dutch). Preventive healthcare and standardised medical examinations are performed at the CLB at certain ages determined by law, including weight and height measurements. All the children participating in this study were examined and measured by a CLB nurse (3 different CLB nurses) in a standardised way (according to the protocol ‘Vlaamse vereniging voor Jeugdgezondheidszorg vzw (VWVJ) & Vlaamse Groeicurven’).15 For these measurements, children were only wearing underwear. Weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg, using an electronic weighing scale (Seca 841) and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm in standing position, using a rigid stadiometer (Seca 220). The stadiometer was checked for accuracy and the scale was calibrated before starting the examination of each class of children. In this manuscript the weight and height measurements performed by CLB nurses are indicated as ‘index’ measured weight and height. Nurses did not know whether the child belongs to the intervention or control group and they had no access to the parent-reported weight and height estimates.

Procedures

The school directors of the selected schools approved the study protocol and gave permission to run the study in their school. The directors of the schools and the teachers of the classes participating in the study were given detailed information and instructions about the study.

The teachers of the participating classes were asked to distribute the questionnaire (including the instruction leaflets in the intervention group only) among the parents of the children about 14 days before the planned medical examination in the CLB. An informed consent was attached, in which parents were informed and invited to participate in the study, without being aware that validation of anthropometric measurements was part of the study. The completed questionnaires and the signed informed consents were returned to the school in a sealed envelope.

All procedures were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Our randomised controlled trial was not registered with a clinical trials registry as we were not seeking to modify a health outcome.

Statistical analysis

BMI (kg/m2) was calculated from parent-reported and index measured heights and weights. Underweight, overweight and obesity were identified using age-specific and gender-specific international (International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)) cut-off points.16 17

Differences in mean parent-reported and index measured weight, height and BMI, and corresponding differences in prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity were assessed using paired t test and McNemar's test, respectively. Limits of agreement were estimated from the SD of differences from the index measurements (mean difference±1.96 SD), considering the measurements derived from the CLB nurses as index measurements. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) between measured and reported values were calculated as a measure of overall association. All analyses were also performed while correcting for the cluster design (using mixed models) and gave similar results. However, as the proportion of variance between clusters to the total variance was less than 0.5%, the final results have not been corrected for cluster design.

When identifying underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity, misclassification was defined as discordance between BMI categories, determined by parent-reported and parent-measured BMI versus nurse-measured BMI. The weighted κ statistic was calculated to determine agreement between parent-reported and measured index BMI status adjusted for chance, using a linear set of weights.18 κ Values <0.20 are often considered as ‘poor’ agreement, 0.21–0.40 as ‘fair’ agreement, 0.41–0.60 as ‘moderate’ agreement, 0.61–0.80 as ‘good’ agreement and 0.81–1.00 as ‘excellent’ agreement.18

Sensitivity was defined as the proportion of children categorised into a certain BMI category (eg, overweight) based on measured BMI that was also categorised into the same BMI category when using parent reports (true positives). Specificity was defined as the proportion of children assigned as not having a certain BMI status (eg, overweight) when using measured index BMI that was also not assigned to that same BMI category when using the parent-reported data (true negatives).

The SPSS for Windows V.20 was used for data management and all statistical analyses. Unless reported differently, a p value of 0.05 (two-sided) was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 266 (pre)school children were officially registered in the 17 sampled classes in five different schools. Complete questionnaires were returned by 164 children (62%). These children had a mean age of 6.8 years (SD 1.4 years) and an age range from 4.0 to 9.9 years (15.2% 4–5.9 years; 60.4% 6–7.9 years; 24.4% 8–9.9 years).

Both sexes were similarly represented in the study (47% girls) and 51% of the children who participated were included in the intervention group (table 1). Only 63% of the intervention group parents reported they made the effort to measure their child's weight and height according to the instruction folders distributed. Therefore, the authors will present results for two intervention comparisons: (1) the total sample of 164 cases (all 83 intervention vs 81 control); and (2) the select group of children from the intervention group whose parents reported that weight and height were measured at home according to the instructions given in the folders that were distributed (52 intervention vs 81 control).

Table 1.

Description of the study populations

| Percentage of total population (n=164) | Percentage of control group (n=81) | Percentage of total intervention group (n=83) | Percentage of measuring intervention group* (n=52) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person who completed questionnaire | ||||

| Father | 18.4 | 14.8 | 21.7 | 19.2 |

| Mother | 78.0 | 81.5 | 74.7 | 80.8 |

| Other | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 0.0 |

| Method used to report weight and height | ||||

| Weight measured at home | 76.9 | 72.7 | 81.0 | 100 |

| Height measured at home | 68.8 | 64.1 | 73.4 | 100 |

| Time of the day when the parents measured their child's weight and height | ||||

| Morning | 31.3 | 33.3 | 30.3 | 35.4 |

| Afternoon | 22.9 | 24.6 | 21.2 | 16.7 |

| Evening | 45.8 | 43.1 | 48.5 | 47.9 |

| Birth country child | ||||

| Belgium | 84.1 | 82.7 | 85.5 | 86.5 |

| Other country | 12.2 | 14.8 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Missing | 3.7 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 3.8 |

| Educational level proxy | ||||

| Lower secondary education | 8.5 | 9.8 | 7.2 | 7.7 |

| Higher secondary education | 22.0 | 16.1 | 27.8 | 19.2 |

| Higher education (eg, bachelor) | 31.2 | 30.9 | 31.3 | 38.4 |

| University degree (eg, master degree) | 35.9 | 39.5 | 32.5 | 34.6 |

| Missing | 2.4 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Income allows family to buy healthy food | ||||

| Sufficiently | 81.1 | 80.2 | 81.9 | 82.7 |

| Mostly sufficiently | 12.8 | 16.0 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Seldom sufficiently | 1.2 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 3.8 |

| Insufficiently | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 1.9 |

*Children from the intervention group whose weight and height had been measured at home according to the instructions given in the folders that were distributed.

Overall, 78% of the questionnaires analysed were answered by the mother of the child, with relatively more in the control group (81.5%) than in the intervention group (74.7%; table 1). About 45% of the children had been measured in the evening and about 1/3 in the morning (the remaining in the afternoon). Relatively more parents reported measuring their child's weight and height at home in the intervention group than in the control group (table 1). However, a χ2 test comparing the proportions of parents measuring indicated that this difference was not significantly different between control and intervention groups (p=0.219 and p=0.208 for weight and height measurements, respectively).

When comparing the socioeconomic variables in table 1 between the intervention and control groups, our results showed slightly higher educated levels of the person who reported the child's weight and height in the control group than in the intervention group. However, these education levels were not significantly different between control and intervention group (p=0.217).

From table 2 it can be seen that no significant differences were found in mean height reported by the parents compared with the mean height measured by the CLB nurse (index measured) for both the intervention group and the control group. However, the mean weight reported by the parents was significantly underestimated in comparison with the weight measured by the CLB nurse, in both segments of the intervention group. This resulted in a significant underestimation of mean BMI reported by the parents from the total intervention group compared with the BMI calculated from the index data (table 2). Mean differences between means of parent reported and measured BMI were, however, not significantly different from index measurements when parents measured their child's weight and height according to the instruction folders distributed in the intervention group.

Table 2.

Accuracy of parent-reported weight and height among preschool children: comparing intervention with control group

| Reporting method used by parents | Parent reported | Index measured | Difference | Pearson correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p Value* | ICC | 95% CI | ||

| Weight (kg) (control group) (n=81) | 24.6 (5.6) | 25.0 (6.0) | −0.43 (2.3) | 0.095 | 0.918 | (0.875 to 0.947) | 0.922 |

| Weight (kg) (intervention group) (n=83) | 23.7 (5.9) | 24.4 (5.9) | −0.69 (1.9) | 0.002 | 0.939 | (0.898 to 0.962) | 0.945 |

| Weight (kg) (intervention group following instructions) (n=52) | 23.6 (6.3) | 24.2 (6.2) | −0.63 (1.5) | 0.004 | 0.965 | (0.932 to 0.981) | 0.970 |

| Height (cm) (control group) (n=81) | 123.6 (8.9) | 123.0 (8.4) | 0.57 (5.1) | 0.317 | 0.823 | (0.738 to 0.882) | 0.824 |

| Height (cm) (intervention group) (n=83) | 121.3 (10.8) | 121.5 (11.1) | 0.20 (3.4) | 0.581 | 0.952 | (0.926 to 0.968) | 0.952 |

| Height (cm) (intervention group following instructions) (n=52) | 120.6 (10.9) | 121.2 (11.1) | −0.63 (2.9) | 0.125 | 0.964 | (0.938 to 0.979) | 0.965 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (control group) (n=81) | 16.0 (2.4) | 16.3 (2.1) | −0.3 (1.9) | 0.108 | 0.633 | (0.483 to 0.747) | 0.641 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (intervention group) (n=83) | 15.9 (2.4) | 16.3 (2.3) | −0.4 (1.5) | 0.017 | 0.772 | (0.662 to 0.848) | 0.783 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (intervention group following instructions) (n=52) | 16.0 (2.4) | 16.3 (2.3) | −0.3 (1.3) | 0.140 | 0.826 | (0.716 to 0.896) | 0.830 |

*According to the paired samples t test.

BMI, body mass index; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

For each dimension (weight, height and BMI), the ICC with index measurements were higher in the group of children whose parents measured their body parameters at home according to the instruction folder than in the children in the control group. Also the Pearson correlation coefficients between index measured and reported weight, height and BMI values indicate that the associations were strongest in the intervention group than in the control group (see table 2). Correction for the time of the day when the children had been measured improved all correlations slightly (in both control and intervention groups). Correlations remained higher for the intervention group than the control group, and were highest in the group of children from the intervention group whose parents used the instruction folders (data not shown).

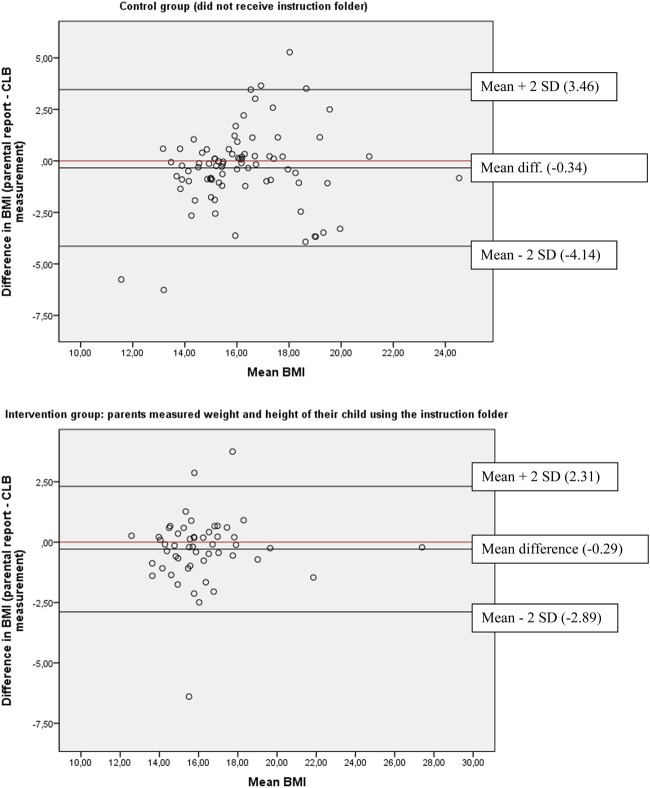

For the three body dimensions (weight, height and BMI), much larger limits of agreement were found for the control group than the intervention group: −4.14 to 3.46 in control group versus −2.89 to 2.31 in intervention group (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot including the mean difference and limits of agreement for BMI in the control group (n=81) and in the intervention group (n=52), respectively. BMI, body mass index; CLB, Centrum voor Leerlingenbegeleiding.

Misclassification analysis indicated that more children were grossly misclassified in the control group than in the two segments of the intervention group, while fewer children were classified correctly (table 3). The percentage of grossly misclassified children was lowest in the intervention group when using only the children whose parents used the instruction folders to measure their child's weight and height. These patterns are reflected in the relative values of the weighted κ statistics, being highest (0.60) for the group of children whose parents reported using the instruction folders to measure their child's weight and height.

Table 3.

Cross-classification analyses for parent-reported (measured vs estimated) and accurately measured (by school nurse) BMI categories*

| Reported vs measured BMI |

Weighted κ (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental report | Same category (%) | Adjacent category (%) | Extreme category (%) | ||

| Control group (n=81) | 65.4 | 29.6 | 5.0 | 0.30 | (0.07 to 0.54) |

| Intervention group (n=83) | 73.5 | 25.3 | 1.2 | 0.51 | (0.28 to 0.74) |

| Intervention group following instructions (n=52) | 78.8 | 19.2 | 1.9 | 0.60 | (0.30 to 0.81) |

*The IOTF cut-off values for determining underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity.

BMI, body mass index; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force.

The validity tests for classifying underweight, overweight and obesity from the parent-reported weight and height, using the index measurements as the criterion, are shown in table 4. The sensitivity for identifying the presence of underweight, overweight and obesity status, based on parent-reported BMI, compared with measured BMI, was lowest in the control group. Also, specificity was lowest in the control group for overweight and obesity, but not for underweight. The κ statistic shows that agreement for underweight, overweight and obesity between parent-reported and index measured values was always higher in the intervention group than in the control group.

Table 4.

Diagnostic values of parent-reported (measured vs estimated) height and weight in detection of BMI categories*

| Reporting method used by parents | Percentage of sensitivity (95% CI) |

Percentage of specificity (95% CI) |

κ statistic (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Intervention group | Intervention group following instructions | Control group | Intervention group | Intervention group following instructions | Control group | Intervention group | Intervention group following instructions | |

| Underweight | 67 (20.7 to 93.8) | 75 (30.0 to 95.4) | 67 (20.7 to 93.8) | 87 (77.9 to 92.8) | 85 (75.3 to 91.0) | 86 (73.3 to 92.9) | 0.22 (−0.25 to 0.69) | 0.26 (−0.16 to 0.67) | 0.27 (−0.26 to 0.80) |

| Overweight/ obese | 43 (21.3 to 67.4) | 60 (35.7 to 80.1) | 70 (39.6 to 89.2) | 89 (79.9 to 94.8) | 96 (87.8 to 98.4) | 98 (87.6 to 99.5) | 0.33 (−0.02 to 0.68) | 0.60 (0.25 to 0.95) | 0.73 (0.30 to 1.16) |

*The IOTF cut-off values for determining underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity.

Control group (n=81); intervention group (n=83); and intervention group following instructions (n=52).

BMI, body mass index; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force.

Discussion

Principal findings

The mean measurements for height, weight and BMI of children obtained from parents are very similar to those obtained from well-trained clinic staff. Nevertheless, there is evidence of some small average bias, particularly in child weight, even if parents reported using the measurement instruction leaflets. Although the mean parent-reported weight was slightly more underestimated in the intervention group (that received the instruction leaflet for measuring weight) than in the control group relative to the index weights, the correlations between the parental reports and the index measurements were higher in the intervention group than in the control group. Furthermore, there was considerably less misclassification into valid BMI categories for the whole intervention group, and especially for that segment who reported using the instruction leaflets. This pattern suggests that most of the parental deviations from the index measurements were probably due to random errors of measurement. A more in depth look at the data revealed that for parental estimations of the child's body weight, indeed both underestimations and overestimations of the real weight appeared, while parental measurements of their child's weight (using their own scale) were mainly underestimated, revealing systematically underestimation of true weight when using home scales. Although these systematic underestimations might be responsible for the decreased accuracy in estimating the mean weight of the children when using parental measurements, these systematic errors do not influence the ranking of the children according to their body weight, which explains better correlations and diagnostic measurements (data not shown).

Our results in Flemish families indicate that a large proportion of parents in the control group reported that they measured their children, even without the additional instruction provided by the leaflets distributed as the intervention. While the intervention appears to have increased the proportion of parents who measured their children, the main net effect seems to have been to reduce the amount of random errors relative to the index measurements, that is, that the leaflets help standardise parental measurements relative to accepted protocols.

Comparison with previous studies

In a previous validation study in 2006 among Flemish preschoolers, the authors already highlighted the weak validity of parent-reported weight and height values for classifying preschool-aged children in BMI categories.7 These results were recently confirmed by other researchers in German children.19 More exhaustive analyses of the validity study of parent-reported weight and height among preschool-aged children in Flanders revealed that parent-reported values were more accurate when parents made the effort to weigh and measure their child at home than when children's weight and height were guessed at by the parents.11 An exhaustive review of Himes10 also revealed the doubtful validity of parent-reported weight and height values for classifying children as underweight, overweight or obese. Himes also highlighted the importance of motivating the parents to measure their child's weight and height at home in an attempt to improve these parental reports, as these parent-reported weight and height values will remain the main body fatness indicators in many large-scale surveys where measurements by trained researchers are not feasible because of the high cost involved.

To our knowledge no other studies have evaluated the validity of instruction folders to improve the validity of parent-reported weight and height measurements further. Therefore, the authors were not able to compare these validity results obtained in this intervention study with other studies.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study investigating the validity of instruction folders for parents to accurately measure their child's weight and height at home by comparison with simple estimated parental reports. An important strength of this study is the high level of standardisation in the reference measurements performed by the experienced and trained CLB nurses, and the inclusion of both parent-measured and parent-estimated child dimensions.

Some limitations of this study are worth noting. Data were available only for children whose parents completed the questionnaire. Children who were measured by a CLB nurse but whose parents did not complete the questionnaire were excluded from the analyses. It is possible that respondents were more willing, or more able, than non-respondents to provide accurate assessments of their children's weight and height. Therefore, the errors between parentally reported and measured weight and height in this sample may be underestimates of the true errors, since almost 40% of the parents refused to complete the questionnaire. However, to help minimise underestimation of the errors, the participants were not aware of the future intended comparison between reported and measured values.

In this study the criterion examination by the CLB nurses was performed about 2 weeks after completion of the questionnaire. As there might be up to 2 weeks between the two assessments, the true weight and height might change during this period. However, large changes, which might influence the present results, are unlikely to have occurred during that period.

Future research should investigate the validity and feasibility of these instruction folders further for use in large-scale multicentric studies where standardisation of the measurements is very important but where index measurements by trained staff members are not feasible. Furthermore, it would be important to get an idea on the time needed for such parental weight and height measurements at home (for instance via a feasibility study registering the time of the measurements). For proxy reporting that occur ‘on the spot’ during a telephone or face-to-face survey, instructions on measuring the child's height and weight would need to be given to the participants prior to the interview and could thus incur additional costs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the degree of inaccuracy of parent-reported weight and height values in classifying preschool children as being underweight, overweight or obese. However, the important differences found between parent-measured weight and height values when using the newly developed instruction folders compared with parent-estimated values suggest the importance of motivating and instructing parents to measure their child at home when the study design includes the use of parent reports for weight and height values of their children at least when aiming to classify the children in the correct BMI category. The instruction folders developed and validated in this study can serve as an example for future large-scale surveys in children that rely on parental weight and height reports.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the schools and parents who participated in this project and generously volunteered their time and knowledge. They are grateful to the nurses and workers of the Centrum voor Leerlingenbegeleiding (CLB), more in particular Lieve Van Neck, Joke Vander Vekens, Mieke Van Driessen and Ann-Sophie Roobrouck who made this study possible. The authors also would like to thank Ms Kathleen Van Landeghem from KaHo Sint-Lieven, Gebroeders Desmetstraat 1, 9000 Gent, Belgium, because of her involvement, as supervisor, in the bachelor manuscript that was linked to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: The original idea for the analyses came from IH and JHH. CB and ES developed the instruction folders and did all of the data management and analysis under the supervision of IH, TDV and JHH. IH led on the writing of the paper but all coauthors contributed equally to different drafts of the paper and suggested analysis for the manuscript. ADC supervised the local fieldworkers. DDB, SDH, PP and NS assisted in the conceptualisation of the study and in the interpretation of the results. All authors have read the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee (EC) of the Ghent University Hospital granted ethical approval for the study. The EC has read and approved the study protocol and all the documents that were handed out to the participants (including the informed consent form).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics 1998;101:518–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huybrechts I, Matthys C, Pynaert I, et al. Flanders preschool dietary survey: rationale, aims, design, methodology and population characteristics. Arch Public Health 2008;66:5–25 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Ogden CL. Childhood overweight prevalence in the United States: the impact of parent-reported height and weight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1574–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom B, Cohen RA, Vickerie JL, et al. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2001. Vital Health Stat 10, 2003:1–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey AN, Schiller JS, Tai DA. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. Vital Health Stat 10, 2004:1–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Osborn L, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Early Childhood Health, 2000. Vital Health Stat 1, 2002:1–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huybrechts I, De Bacquer D, Van Trimpont I, et al. Validity of parentally reported weight and height for preschool-aged children in Belgium and its impact on classification into body mass index categories. Pediatrics 2006;118:2109–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholtens S, Brunekreef B, Visscher TL, et al. Reported versus measured body weight and height of 4-year-old children and the prevalence of overweight. Eur J Public Health 2007;17: 369–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akerman A, Williams ME, Meunier J. Perception versus reality: an exploration of children's measured body mass in relation to caregivers’ estimates. J Health Psychol 2007;12:871–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Himes JH. Challenges of accurately measuring and using BMI and other indicators of obesity in children. Pediatrics 2009;124:S3–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huybrechts I, Himes JH, Ottevaere C, et al. Validity of parent-reported weight and height of preschool children measured at home or estimated without home measurement: a validation study. BMC Pediatrics 2011;11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tillmann V, Clayton PE. Diurnal variation in height and the reliability of height measurements using stretched and unstretched techniques in the evaluation of short-term growth. Ann Hum Biol 2001;28:195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siklar Z, Sanli E, Dallar Y, et al. Diurnal variation of height in children. Pediatr Int 2005;47:645–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Routen AC, Edwards MG, Upton D, et al. The impact of school-day variation in weight and height on National Child Measurement Programme body mass index-determined weight category in year 6 children. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:360–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vrije Universiteit Brussel Laboratorium voor Antropogenetica. Growth Charts Flanders 2004, 2004

- 16.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, et al. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 2007;335:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brettschneider AK, Ellert U, Schaffrath RA. Comparison of BMI derived from parent-reported height and weight with measured values: results from the German KiGGS study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:632–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.