SUMMARY

We previously showed that asunder (asun) is a critical regulator of dynein localization during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Because the expression of asun is much higher in Drosophila ovaries and early embryos than in testes, we herein sought to determine whether ASUN plays roles in oogenesis and/or embryogenesis. We characterized the female germline phenotypes of flies homozygous for a null allele of asun (asund93). We find that asund93 females lay very few eggs and contain smaller ovaries with a highly disorganized arrangement of ovarioles in comparison to wild-type females. asund93 ovaries also contain a significant number of egg chambers with structural defects. A majority of the eggs laid by asund93 females are ventralized to varying degrees, from mild to severe; this ventralization phenotype may be secondary to defective localization of gurken transcripts, a dynein-regulated step, within asund93 oocytes. We find that dynein localization is aberrant in asund93 oocytes, indicating that ASUN is required for this process in both male and female germ cells. In addition to the loss of gurken mRNA localization, asund93 ovaries exhibit defects in other dynein-mediated processes such as migration of nurse cell centrosomes into the oocyte during the early mitotic divisions, maintenance of the oocyte nucleus in the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte in late-stage egg chambers, and coupling between the oocyte nucleus and centrosomes. Taken together, our data indicate that asun is a critical regulator of dynein localization and dynein-mediated processes during Drosophila oogenesis.

Keywords: Drosophila, oogenesis, dorsal fate determination, centrosomes, dynein

INTRODUCTION

Drosophila oogenesis is a powerful model system for studying various aspects of cell and developmental biology such as control of the cell cycle, axis formation, epithelial morphogenesis, cellular polarity, and cell fate determination. A wild-type Drosophila female has a pair of ovaries, each made up of 16 –18 independent “egg assembly lines” known as ovarioles (Bastock and St Johnston, 2008; Spradling, 1993). Each ovariole consists of a specialized anterior region (the germarium) where the progeny of germline and somatic stem cells are organized into distinct egg chambers. Each egg chamber consists of a cyst of 16 germ cells (15 nurse cells and 1 oocyte) interconnected by cytoplasmic bridges called ring canals and surrounded by a single layer of somatic follicle cells. The development of the egg chambers into mature eggs has been divided into 14 stages based on egg chamber morphology (Spradling, 1993). The polarity of the mature egg, formed at the end of oogenesis, is characterized by certain prominent structures: an anteriorly positioned, cone-shaped micropyle that facilitates sperm entry prior to fertilization and, located above the micropyle, a pair of dorsal appendages that facilitate embryonic respiration.

Determination of eggshell polarity depends on key patterning events that occur during Drosophila oogenesis. Within the germarium, centrosomes migrate from the nurse cells into the future oocyte in a manner dependent on a branched cytoplasmic organelle called the fusome, which extends into all the germline cells within a cyst (Bolivar et al., 2001; Lin et al., 1994). A microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) forms in the oocyte posterior; microtubules originating from this MTOC pass through cytoplasmic bridges into adjacent nurse cells and are required for transport of maternal mRNAs and proteins from the nurse cells into the oocyte (Pokrywka and Stephenson, 1991; Theurkauf et al., 1992). Transport and asymmetric localization within the oocyte of oskar (osk), nanos (nos), bicoid (bcd), and gurken (grk) transcripts are critical for proper establishment of the embryonic body axes (Becalska and Gavis, 2009).

grk mRNA is localized to the posterior of the Drosophila oocyte prior to its translation to generate Gurken (Grk) protein, a TGFα-like ligand, which signals posterior follicle cells to adopt a posterior fate (Gonzalez-Reyes et al., 1995; Neuman-Silberberg and Schupbach, 1993). The posterior follicle cells in turn trigger reorganization of the microtubule cytoskeleton of the oocyte that promotes localization of bcd transcript to the anterior pole and osk and nos transcripts to the posterior pole, thus establishing the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo. This microtubule reorganization also results in migration of the oocyte nucleus to the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte (Zhao et al., 2012). grk mRNA, which associates with the oocyte nucleus, begins to accumulate in this region (Neuman-Silberberg and Schupbach, 1993). The resulting localized secretion of Grk protein, which signals to overlying dorsal-anterior follicle cells, initiates a signaling cascade that ultimately establishes the dorsal-ventral axis of the embryo (Peri and Roth, 2000; Sen et al., 1998; Van Buskirk and Schupbach, 1999; Wasserman and Freeman, 1998).

The microtubule motors, dynein and kinesin, are critical for the transport of various mRNAs to their specific sites during Drosophila oogenesis (Becalska and Gavis, 2009; Duncan and Warrior, 2002; Januschke et al., 2002). Localization of grk mRNA, which is required for the formation of both major axes, is dependent on the minus-end-directed motor, dynein (MacDougall et al., 2003; Rom et al., 2007; Swan et al., 1999). Dynein is a large complex composed of four types of subunits: heavy, intermediate, light intermediate, and light chains (Hook and Vallee, 2006; Susalka and Pfister, 2000). Dynein regulates multiple cellular processes such as organelle transport, chromosome movements, nucleus-centrosome coupling, nuclear positioning, and spindle assembly (Anderson et al., 2009; Gusnowski and Srayko, 2011; Hebbar et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2011; Jodoin et al., 2012; Salina et al., 2002; Sitaram et al., 2012; Splinter et al., 2010; Stuchell-Brereton et al., 2011; Wainman et al., 2009). During Drosophila oogenesis, dynein is required within the germ cells for maintenance of fusome integrity, centrosome migration, oocyte determination, migration of the oocyte nucleus, transport into the oocyte of various mRNAs and proteins that play critical roles in axis determination of the embryo, and localization of these mRNAs and proteins within the oocyte (Bolivar et al., 2001; Januschke et al., 2002; Lei and Warrior, 2000; McGrail and Hays, 1997; Schnorrer et al., 2000; Swan et al., 1999). Dynein is also important within the somatic follicle cells for maintenance of their apical-basal polarity as well as for the migration of the border cells from the anterior of the egg chamber to the anterior of the oocyte (Horne-Badovinac and Bilder, 2008; Van de Bor et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012).

We previously identified asunder (asun) as a critical regulator of dynein localization during Drosophila spermatogenesis (Anderson et al., 2009). Dynein enrichment on the nuclear surface of G2 spermatocytes and round spermatids is lost in asun testes; as a result, asun male germ cells exhibit defects in nucleus-centrosome and nucleus-basal body coupling. Northern blot analysis of Drosophila tissues revealed that asun transcripts, while detected in the testes, were present at much higher levels in ovaries and early embryos, suggesting that asun may play roles in oogenesis and/or embryogenesis (Stebbings et al., 1998). In this study, we investigate the role of asun during Drosophila oogenesis by characterizing the phenotypes of females homozygous for a null allele of asun (asund93). We provide evidence to show that, similar to its role in spermatogenesis, asun is required for regulating dynein localization and dynein-mediated processes within the germ cells such as nuclear positioning, centrosome migration, and dorsal-ventral patterning during Drosophila oogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks

y w was used as “wild-type” stock. The asund93 allele was previously described (Sitaram et al., 2012). png50 and png1058 were gifts from T. Orr-Weaver (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA). TrolGFPZCL1700, which was used for observing the localization of Drosophila Perlecan, was a gift from A. Page-McCaw (Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN).

Transgenesis

A 3.6-kb genomic fragment containing asun and its flanking regions (Fig. 1A) was PCR-amplified from BAC clone BAC37I18 (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center, Indiana University, IN) and subcloned into modified pCaSpeR4 for expression of full-length ASUN under control of its endogenous promoter (asun rescue construct). The following primers were used: 5′-GCA TGG CCG GCC ACT GCA CAA GAT T-3′ and 5′-GAC TGG CGC GCC CCG AAG AAA AGT T-3′. Transgenic lines carrying P[asunFL] were generated by P-element-mediated transformation via embryo injection (Rubin and Spradling, 1982).

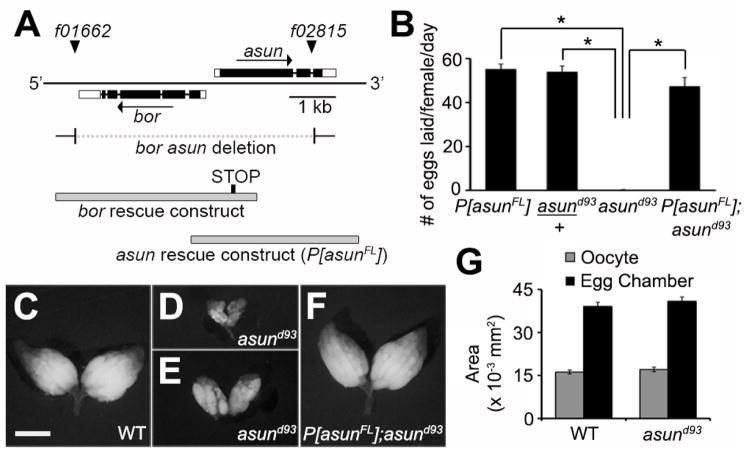

Figure 1. Reduced egg-laying rates and ovary size of asund93 females.

(A) Schematic diagram of the asun gene region. Coding regions and UTRs are represented as filled and unfilled boxes, respectively, introns as thin lines, and piggyBac transposons f01662 and f02815 as triangles. Breakpoints of a bor asun two-gene deletion (generated through FLP-mediated recombination of FRT sites within the transposons) and design of a bor transgene are shown; as previously described, asund93 flies are homozygous for the bor asun two-gene deletion and bor transgene (Sitaram et al., 2012). Design of the full-length asun transgene (P[asunFL]) generated for this study is also shown. (B) Quantification of egg-laying rates for females of the indicated genotypes. Asterisks, p<0.0001. (C–F) Whole ovaries dissected from 2-day old fattened females of the indicated genotypes. Ovaries from asund93 females (D,E) are highly reduced in size compared to those from wild-type (C) or P[asunFL];asund93 rescue (F) females. Scale bar, 1 mm. (G) Quantification of the average area of stage 10B egg chambers and oocytes isolated from females of the indicated genotypes.

Egg-laying assay

Females (2–4 days old) of each genotype tested were placed in a bottle with wild-type males, fattened with wet yeast for two days, and transferred to egg-collection chambers (five females and five wild-type males per chamber; two chambers per genotype) at 25°C. The number of eggs laid by females in each collection chamber was counted each day up to five days. Statistical analysis of the average number of eggs laid per day by females of the indicated genotypes was performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test.

Cytological analysis of fixed ovaries

Ovaries were dissected and teased apart in Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), fixed for 18 minutes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 4% formaldehyde, washed for 2 hours in PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBT), incubated for 3 hours in PBT plus 5% normal goat serum (PBT-NGT), and incubated overnight at 4°C in PBT-NGT containing primary antibodies. Ovaries were then washed for 2 hours in PBT, incubated for 4 hours in PBT-NGT containing fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, incubated in PBT plus 0.5 μg/ml DAPI for 6 minutes, washed for 2 hours in PBT, rinsed once in PBS, and mounted in Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Life Technologies). All steps were done at room temperature unless otherwise noted. For all experiments, ovaries from all genotypes tested were dissected in parallel and fixed/stained under identical conditions. For staining with anti-PLP antibody, the same protocol was followed except that ovaries were fixed with 100% methanol at −20°C for 10 minutes and rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of methanol in PBT before the first PBT wash.

Primary antibodies directed against the following proteins were used: dynein heavy chain (P1H4, 1:120; gift from T. Hays, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN), PLP (1:500; gift from J. Raff, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), lamin (ADL67.10, 1:500, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB], Iowa City, IA), α-spectrin (3A9, 1:20, DSHB), Orb (4H8+6H4, 1:20, DSHB), DE-Cadherin (DCAD2, 1:20, DSHB), aPKC (sc216, 1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX), Fasciclin III (7G10, 1:3, DSHB), and Gurken (1D12, 1:100, DSHB). Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (A12379, 1:250, Life Technologies) was used to label F-Actin. Wide-field fluorescent images were obtained using an Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with Plan-Fluor 40X objective (all micrographs presented unless otherwise indicated). Confocal images were obtained with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope and Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence (LAS-AF) software using maximum-intensity projections of Z-stacks collected at 0.75 μm/step with a 63X objective. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analyses of data.

Egg-chamber area analysis

Ovaries were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and stained with Alexa Fluor phalloidin (Life Technologies) to mark actin at the cell membranes. A Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope was used to obtain images of optical sections of individual stage 10B egg chambers such that the largest areas were obtained. Areas of total egg chambers (oocyte + nurse cells) and oocytes alone were calculated using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). 20 egg chambers were imaged per genotype for the calculation of egg chamber and oocyte area. Stage 10B egg chambers were identified by their follicle cell morphology.

Cytological analysis of fixed embryos

Embryos (0–2 hours) were collected on grape plates, dechorionated in 50% bleach, and devitellinized by shaking in a solution of methanol and heptane (1:1). Embryos were then stained with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide plus 1 mg/ml RNase A in PBT for 20 minutes, washed thrice with PBT, once with 50% methanol in PBT, and thrice with 100% methanol. Embryos were cleared and mounted in clearing solution (2:1 benzyl benzoate:benzyl alcohol). Wide-field fluorescent images were obtained using an Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon) with Plan-Apo 20X objective.

Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization

Whole-mount enzymatic in situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Suter and Steward, 1991). Fluorescent in situ hybridization was performed following the same protocol with the following modifications: Cy3-conjugated digoxigenin antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) replaced alkaline phosphatase-conjugated digoxigenin antibody, and the development step was omitted. Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were synthesized by in vitro transcription using a digoxigenin RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Antisense probes were prepared using the following full-length cDNA clones: grk (gift from A. Page-McCaw, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville TN), bcd, and osk (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center). No significant signal was observed in control experiments using sense probes. Fluorescent in situ hybridization images were obtained using a Zeiss Apotome mounted on an Axio ImagerM2 with a 20X/0.8 Plan-Apochromat objective, and images were acquired with an AxioCam MRm camera (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Enzymatic in situ hybridization images were obtained using a Zeiss LumarV12 fluorescence stereomicroscope with a 1.5X Neolumar objective (zoomed to 80X), and images were acquired with an AxioCam MRc camera (Zeiss).

Immunoblotting

Ovaries from newly eclosed females or embryos (0–2 hour) were homogenized in nondenaturing lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (25 μg protein/lane) and immunoblotting using standard techniques. Primary antibodies were used as follows: anti-dynein heavy chain (P1H4, 1:2000), anti-dynein intermediate chain (74.1, 1:250, Santa Cruz), anti-Cyclin B (F2F4, 1:100, DSHB), and anti-beta-tubulin (E7, 1:1000, DSHB). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to detect primary antibodies by chemiluminescence.

RESULTS

asun is required for oogenesis

To address whether asun plays a role in Drosophila oogenesis, we first tested the fertility of females homozygous for a null allele of asun (asund93) that we previously generated (Fig. 1A) (Sitaram et al., 2012). We found that asund93 females had a severely reduced egg-laying rate (average of <1 egg/day/female compared to 55 eggs/day/female for a control stock; Fig. 1B). Heterozygous asund93 females, however, exhibited egg-laying rates comparable to that of control females, indicating that asun is a haplosufficient locus (Fig. 1B). To confirm that the egg-laying defect of asund93 females was a direct consequence of loss of asun function, we generated transgenic Drosophila lines (P[asunFL]) expressing full-length ASUN under control of its endogenous promoter (Fig. 1A). The egg-laying rate of asund93 females was restored nearly to control levels by introduction of the P[asunFL] transgene (Fig. 1B).

We then sought to determine if asund93 females had gross defects in oogenesis that could account for their reduced egg-laying rate. We dissected whole ovaries from two-day old female flies fattened by addition of wet yeast paste to their food. Ovaries isolated from a majority of asund93 females were considerably smaller in size than those isolated from wild-type females or asund93 females carrying the P[asunFL] transgene (herein referred to as “rescued asund93” line) (Fig. 1C–F). To test if the reduced size of asund93 ovaries was due to a decrease in egg chamber and/or oocyte size, we measured the area of stage 10B egg chambers and oocytes (as a representative stage) isolated from wild-type or asund93 females. We found no striking difference in stage 10B egg chamber or oocyte area between these genotypes (Fig. 1G), suggesting that the reduction in asund93 ovary size might be due to defects in proper progression to later developmental stages of oogenesis.

Whereas individual ovarioles isolated from wild-type or rescued asund93 ovaries were clearly ordered by increasing stages of development (Fig. S1A,C), the arrangement of a majority of ovarioles isolated from asund93 ovaries was highly disorganized (Figs S1B, 1E). Ovarioles from the larger asund93 ovaries typically contained early- and late-stage egg chambers with a paucity of intermediate stages (for example, Fig. S1B shows an asund93 ovariole with two mature oocytes to the right immediately adjacent to a stage 5 egg chamber). Thus, the mature oocytes that are occasionally produced by asund93 females tend to accumulate within the ovaries. These findings suggest that, in addition to abnormal oogenesis, asund93 females have defects in related processes downstream of oogenesis such as ovulation, mating, sperm storage, fertilization, and/or egg laying (Sun and Spradling, 2013). We did not observe any overt differences, however, in the morphological appearance of the reproductive glands (parovaria, spermathecae, or seminal receptacles) of asund93 females compared to wild-type controls (Fig. S1D,E).

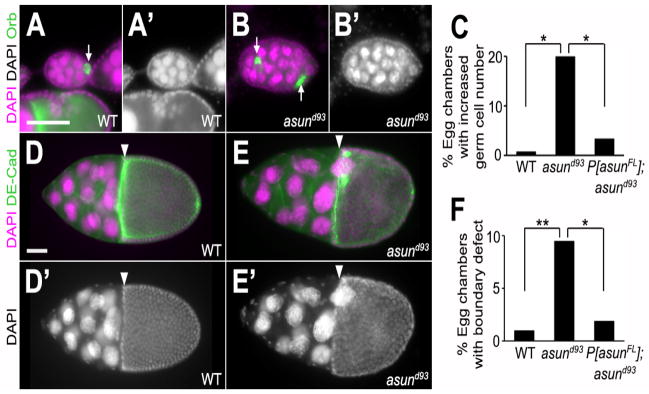

asund93 egg chambers exhibit structural defects

We occasionally observed abnormal numbers of oocytes and nurse cells within asund93 egg chambers. Whereas wild-type egg chambers normally contain 15 nurse cells and one oocyte, we found that 20% of asund93 egg chambers (compared to <1% and <4% of wild-type and rescued asund93 egg chambers, respectively) contained an increased number of germ cells (nurse cells and oocyte), possibly as a consequence of fusion of two or more egg chambers (Fig. 2A–C). Furthermore, we occasionally observed disruption of the follicle cell border that clearly demarcates nurse cells and the oocyte in wild-type egg chambers at or beyond stage 10 (Fig. 2D,D′); in 10% of asund93 egg chambers at or beyond stage 10 (compared to 1% and 2% of wild-type and rescued asund93 egg chambers, respectively), nurse cells appeared to protrude across this border and into the oocyte (Fig. 2E,E′,F).

Figure 2. Defects in the cellular composition and arrangement of asund93 egg chambers.

(AB′) Stage 5 egg chambers stained for DNA (magenta; grayscale in A′ and B′) and Orb (green; oocyte marker) from wild-type and asund93 ovaries (dorsal, top; anterior, left). Wild-type egg chambers (A,A′) contain 15 polyploid nurse cells and 1 haploid oocyte. asund93 ovaries occasionally contain compound/fused egg chambers (B,B′). White arrows point to oocytes. (C) Quantification of fused egg chamber defect in ovaries of indicated genotypes (>250 chambers scored per genotype). Asterisks, p<0.0001. (D–E′) Stage 10 egg chambers stained for DNA (magenta; grayscale in D′ and E′) and DE-cadherin (green; cell membrane marker) from wild-type and asund93 ovaries (dorsal, top; anterior, left). There is a clear boundary (white arrowhead) between the nurse cells and the oocyte in stage 10 wild-type egg chambers (D,D′). Nurse cells occasionally extend past this boundary in asund93 stage 10 egg chambers (E,E′). (F) Quantification of nurse cell-oocyte boundary defect in ovaries of indicated genotypes (>200 chambers scored per genotype). Single asterisk, p=0.0006; double asterisk, p<0.0001. Scale bars, 50 μm.

asun-derived embryos do not phenocopy png mutants

ASUN was identified in an in vitro screen for substrates of the serine/threonine protein kinase encoded by pan gu (png), a critical regulator of the S-M cell cycles of early embryogenesis in Drosophila (Fenger et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2005; Shamanski and Orr-Weaver, 1991). Based on this association, we assessed asund93-derived embryos for the presence of png-like phenotypes. We found that asund93-derived embryos did not exhibit the giant nuclei phenotype that is characteristic of png-derived embryos (Fig. S2A–D). Furthermore, we did not observe genetic interaction between png and asun: introduction of a single copy of asund93 into the png50 background failed to modify the png50 giant nuclei phenotype (Fig. S2E). PNG kinase mediates derepression of translation during early embryogenesis, thereby ensuring that Cyclin B levels are sufficiently high to promote mitotic entry (Fenger et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2001; Vardy and Orr-Weaver, 2007). In contrast, immunoblotting revealed normal levels of Cyclin B in asund93-derived embryos, suggesting that ASUN is not required for this function (Fig. S2F).

asund93-derived embryos have dorsal-ventral patterning defects

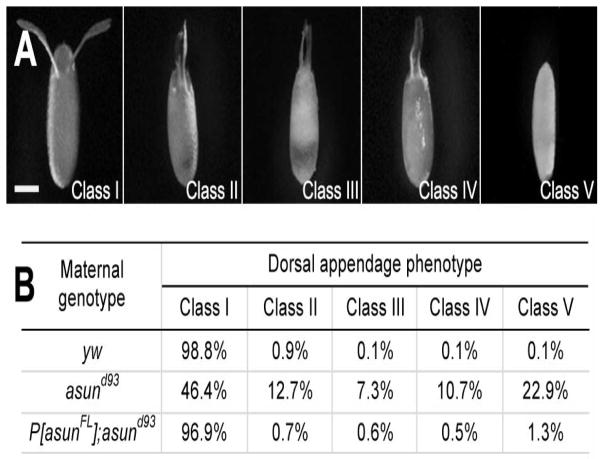

While performing experiments with asund93-derived embryos, we noticed abnormalities in the appearance of the dorsal appendages, a pair of paddle-shaped eggshell structures located on the anterior-dorsal surface of the embryo that form as a result of normal dorsal-ventral patterning events (Schupbach, 1987; Spradling, 1993). We used a previously reported scheme for classifying dorsal appendage defects to characterize this phenotype in asund93-derived embryos (Fig. 3A) (Lei and Warrior, 2000). Class I embryos have a pair of distinct dorsal appendages (wild-type appearance) that are positioned much closer to each other in class II embryos, fused at the base in class III embryos, and fused along their entire lengths in class IV embryos; class V embryos lack visible dorsal appendages. We found that a majority (54%) of asund93-derived embryos had dorsal appendage defects (compared to 1% and 3% for wild-type and rescued asund93 embryos, respectively), including 23% in class V (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that asun is required for proper dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo. We also examined asund93-derived embryos for the presence of the micropyle, another eggshell structure located at the anterior end of the embryo that is required for sperm entry (Spradling, 1993). We found that a small fraction of asund93-derived embryos lacked a micropyle (6% compared to 1% in wild-type and asund93-derived embryos; Fig. S3).

Figure 3. Ventralization of asund93-derived eggs.

(A) Eggs laid by asund93 females. Anterior, top; dorsal side facing outward. Classification scheme for ventralized eggs is adapted from (Lei and Warrior, 2000). Class I eggs appear wild type with a pair of dorsal appendages in the anterior-dorsal region. Dorsal appendages in class II eggs are positioned abnormally close to each other. Class III and class IV eggs contain dorsal appendages that are partially fused at the base and completely fused along the length, respectively. Class V eggs lack dorsal appendages. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of dorsal appendage phenotypes in embryos from wild-type, asund93, and rescued asund93 females (>200 embryos scored per genotype).

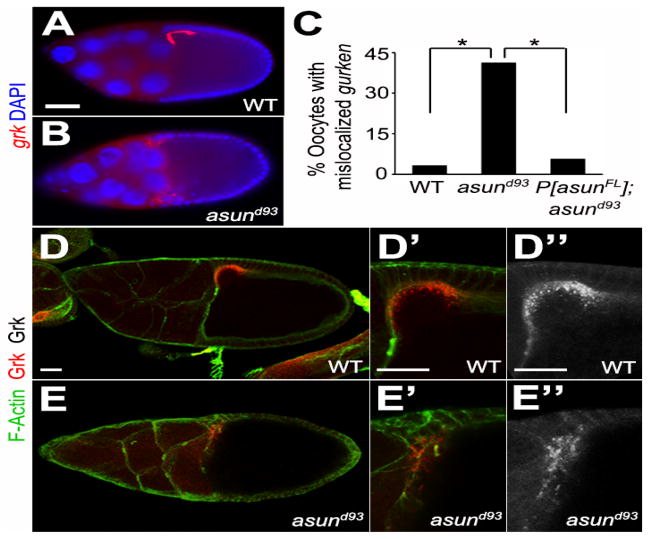

grk mRNA localization is abnormal in asund93 oocytes

The dorsal appendage defects of asund93-derived embryos resemble those reported for embryos produced by females homozygous for a hypomorphic allele of the dynein accessory factor, Lis-1 (Lei and Warrior, 2000). The defect in dorsal-ventral patterning in Lis-1-derived embryos was attributed to loss of anterior-dorsal anchoring of grk mRNA in the oocyte. This asymmetric anchoring of gurken transcripts allows Grk, a TGFα-like protein that acts as a ligand, to asymmetrically activate the EGF receptor homolog, Torpedo/DER, specifically within the dorsal-anterior follicle cells (Neuman-Silberberg and Schupbach, 1993). Dynein light chain, a cargo-binding subunit of dynein, directly binds to grk mRNA and is required for its tight localization to the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte (Rom et al., 2007).

To determine if the dorsal-ventral patterning defects observed in asund93 egg chambers could be due to a loss of dynein-mediated regulation of grk transcripts, we assessed the localization of grk mRNA using both enzymatic and fluorescent in situ hybridization methods. We consistently observed a loss of the tight anterior-dorsal localization of grk transcripts (in 42% and 45% of asund93 egg chambers by enzymatic and fluorescent in situ hybridization, respectively (compared to 4% and 6% of wild-type and rescued asund93 egg chambers, respectively), suggesting that the ventralization of asund93-derived embryos could be a consequence of loss of dynein regulation by ASUN (Figs 4A–C, S4). In contrast, Grk protein appeared to localize normally to the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte in asund93 egg chambers. In ~21% of asund93 egg chambers (31/147 egg chambers), however, the Grk protein localized in a more diffuse manner and with decreased signal intensity compared to 1.3% (3/225 egg chambers) of wild-type egg chambers and 1.7% (5/287 egg chambers) of rescued asund93 egg chambers (Fig. 4D,E). We did not observe any defects, however, in the localization of osk or bcd transcripts, which encode anterior-posterior patterning factors, in asund93 egg chambers (Fig. S5).

Figure 4. Localization of grk transcripts and Grk protein in asund93 oocytes.

(A–B) Fluorescent in situ hybridization of stage 9 egg chambers using grk probe (red). Dorsal, top; anterior, left. grk mRNA localization is tightly restricted to the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte in wild-type egg chambers (A). In asund93 egg chambers, grk transcripts are more diffusely localized throughout the anterior oocyte (B). Scale bars, 50 μm. (C) Quantification of abnormal gurken mRNA localization in wild-type, asund93, and rescued asund93 egg chambers (>100 chambers scored per genotype) by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Asterisks, p<0.0001. (D–E″) Maximum projection confocal images of stage 10 wild-type and asund93 egg chambers stained with Gurken (red; grayscale in D″ and E″) and F-Actin (green; cell membrane marker). Anterior, left; dorsal, top. Gurken protein localizes normally to the anterior-dorsal region of asund93 oocytes (E, E′, E″), but occasionally with a lower intensity and more diffuse pattern than that observed in wild-type oocytes (D, D′, D″). Scale bars, 20 μm.

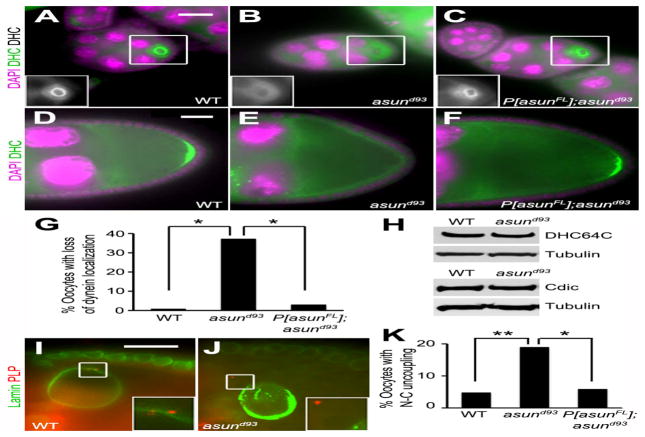

Dynein localization is disrupted in asund93 oocytes

We previously identified asun as a critical regulator of dynein localization in Drosophila spermatogenesis and in cultured mammalian cells (Anderson et al., 2009; Jodoin et al., 2012; Sitaram et al., 2012). To determine if asun performs the same function during Drosophila oogenesis, we examined the localization of dynein in asund93 oocytes using antibodies against the dynein heavy chain. Dynein accumulates within the oocyte in region 2b of the germarium and remains there throughout oogenesis (Li et al., 1994). In early egg chambers of wild-type females, dynein is enriched around the oocyte nucleus, and it localizes to the posterior pole of the oocyte in stage 9 chambers (Fig. 5A,D). We observed a significant loss of dynein localization to these sites in >35% of asund93 egg chambers (compared to <1% and <3% of wild-type and rescued asund93 egg chambers, respectively; Fig. 5A–G). Immunoblotting revealed normal levels of dynein heavy and intermediate chains in asund93 ovaries, suggesting that the loss of dynein localization was not due to instability of core components of the complex (Fig. 5H).

Figure 5. Loss of dynein localization and nucleus-centrosome coupling in asund93 oocytes.

(A–F) Stage 5 (A–C) and stage 9 (D–F) egg chambers stained for dynein heavy chain (green; grayscale in inset) and DNA (magenta). Dorsal, top; anterior, left. asund93 oocytes (B,E) have reduced dynein localization relative to wild-type (A,D) or rescued asund93 (C,F) oocytes. (G) Quantification of loss of dynein localization in egg chambers of indicated genotypes (>200 chambers scored per genotype). Asterisks, p<0.0001. (H) Immunoblot showing wild-type levels of dynein heavy (DHC64C) and intermediate (Cdic) chains in extracts of asund93 ovaries. Loading control, tubulin. (I,J) Stage 10 egg chambers stained for lamin (green; nuclear envelope marker) and PLP (red; centriole marker) (enlarged insets shown below). Dorsal, top; anterior, left. Unlike wild-type oocytes (I), centrosomes are not tightly coupled to the nuclear envelope in asund93 oocytes (J). (K) Quantification of nucleus-centrosome coupling defect in ovaries of indicated genotypes (>100 chambers scored for wild-type and asund93; >50 chambers scored for rescue). Single asterisk, p<0.05; double asterisk, p<0.0025. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Nucleus-centrosome coupling and nuclear positioning are abnormal in asund93 oocytes

The dynein motor is required at multiple steps during Drosophila oogenesis, and its role in this system has been well characterized (Januschke et al., 2002; Lei and Warrior, 2000; McGrail and Hays, 1997; Schnorrer et al., 2000; Swan et al., 1999). Because we observed a loss of dynein localization in asund93 ovaries, we sought to determine if dynein-mediated processes (in addition to grk transcript localization) were disrupted. We observed oocyte nucleus-centrosome coupling defects in 18% of asund93 egg chambers (compared to 5% and 6% in wild-type and rescued asund93 egg chambers, respectively), suggesting that, similar to its role in male germ cells, Drosophila ASUN promotes dynein-mediated association between the nucleus and centrosomes during oogenesis (Fig. 5I–K). Our criterion for categorizing an egg chamber as having uncoupling of the oocyte nucleus and centrosomes was that the egg chamber contained one or more centrosomes completely detached and at a visible distance from the outer membrane of the oocyte nuclear envelope when observed as a two-dimensional image using fluorescence microscopy.

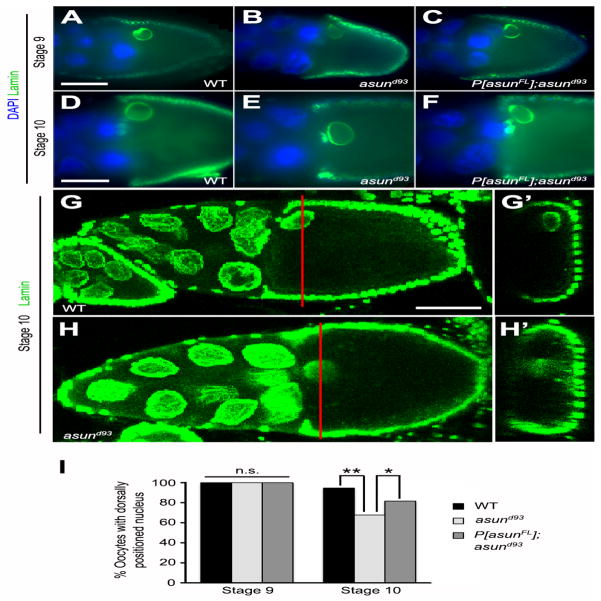

We next assessed the positioning of the oocyte nucleus in asund93 egg chambers. The oocyte nucleus, which normally migrates from the posterior of the oocyte to the future anterior-dorsal region in stage 7 egg chambers, is incorrectly positioned in the absence of dynein or its accessory factors (Januschke et al., 2002; Lei and Warrior, 2000; Swan et al., 1999). This phenotype has been attributed to a failure in the dynein-dependent anchoring of the nucleus at the anterior-dorsal of the oocyte (Zhao et al., 2012). We found that oocyte nuclei in stage 9 egg chambers from wild-type and asund93 females were similarly positioned, suggesting that nuclear migration takes place normally in asund93 females (Fig. 6A–C,I). By stage 10, however, only 67% of asund93 egg chambers (compared to 94% of wild-type egg chambers) exhibited normal anterior-dorsal anchoring of the oocyte nucleus, suggesting that the attachment of the oocyte nucleus at that position is not maintained in the absence of ASUN; introduction of the genomic asun transgene into the asund93 background partially rescued this defect with 81% of these egg chambers containing a properly positioned oocyte nucleus (Fig. 6D–I).

Figure 6. Loss of anterior-dorsal positioning of the oocyte nucleus in asund93 egg chambers.

(A–H′) Wild-type anterior-dorsal positioning of the oocyte nucleus (A,D,G) is observed in stage 9 asund93 oocytes (B), but this positioning is not maintained in stage 10 asund93 oocytes (E,H). This positioning defect is not observed in rescued asund93 oocytes (C,F). (A–F) Epifluorescent micrographs of stage 9 (A–C) and stage 10 (D–F) egg chambers stained for lamin (green; nuclear envelope marker) and DNA (blue). (G–H′) Confocal micrographs of stage 10 egg chambers stained for lamin (green). XY projections (G,H) and corresponding XZ optical sections (G′,H′). Red bars mark positions of corresponding XZ optical sections. Dorsal, top; anterior, left. Scale bars, 50 μm. (I) Quantification of anterior-dorsal positioning of oocyte nucleus in wild-type, asund93, and rescued asund93 stage 9 and 10 egg chambers (>100 chambers scored per genotype). Single asterisk, p<0.006; double asterisk, p<0.0001; n.s., not significant.

asund93 egg chambers exhibit defects in centrosome migration

At the end of the four mitotic germ cell divisions, centrosomes migrate from the nurse cells into the pro-oocyte in a manner dependent on a large cytoplasmic organelle called the fusome, which extends into all 16 cells within a cyst through the ring canals (Bolivar et al., 2001; Grieder et al., 2000). Mutation of dynein heavy chain has been reported to result in loss of fusome integrity and centrosome migration (Bolivar et al., 2001; McGrail and Hays, 1997).

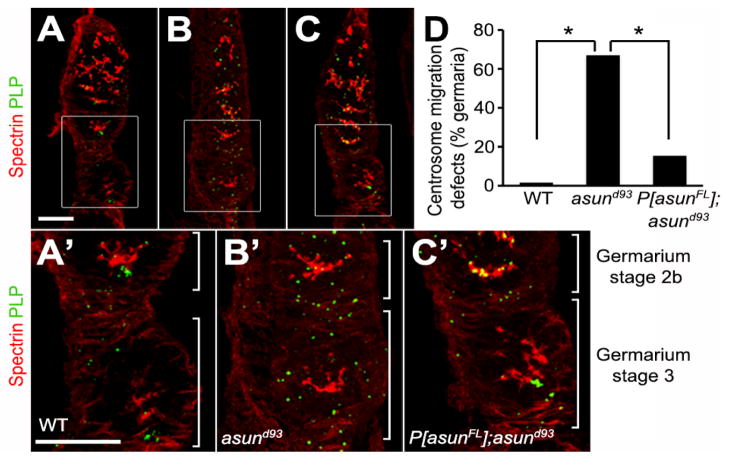

We assessed asund93 germaria for fusome integrity and centrosome migration. We observed no obvious differences in fusome structure in wild-type and asund93 germaria (Fig. 7A,A′,B,B′). asund93 germaria, however, exhibited defects in centrosome migration. Most nurse cell centrosomes have migrated to the oocyte (located at the posterior of the egg chamber) by stage 2B in wild-type germaria (Fig. 7A,A′,D). Centrosome migration was disrupted in 67% of asund93 stage 3 germaria (compared to <2% in wild-type stage 3 germaria) with centrosomes still distributed throughout the cyst (Fig. 7B,B′,D). Centrosome migration was significantly restored in rescued asund93 ovaries (with only 15% of their stage 3 germaria showing disruption of centrosome migration) (Fig. 7C,C′,D). The timing of this process, however, appeared to be delayed: in contrast to wild-type ovaries, most centrosomes were found scattered throughout stage 2B germaria of rescued asund93 ovaries (Fig. 7C′). Possibly as a result of the loss of centrosome migration in asund93 germaria, we observed a decreased number of centrosomes (fewer than five) associated with the oocyte nucleus in 42% of asund93 stage 5 egg chambers (compared to 8% of wild-type egg chambers; Fig. S6).

Figure 7. Centrosome migration defects of asund93 germaria.

(A–C) Projections of confocal sections of wild-type, asund93, and rescued asund93 germaria stained for spectrin (red; fusome marker) and PLP (green; centriole marker). Enlarged insets shown below. Anterior, top; dorsal, left. Within wild-type cysts, most centrosomes have migrated from the nurse cells into the oocyte (located at posterior of egg chamber) by stage 2b of the germarium (A, A′). Centrosomes do not properly migrate into the oocyte in asund93 germaria and are found distributed throughout the entire cyst (B, B′). Centrosome migration occurs in rescued germaria but is delayed (C, C′). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Quantification of centrosome migration defects in wild-type, asund93, and rescued asund93 germaria (>100 germaria scored per genotype). Asterisks, p<0.0001.

Dynein-mediated processes within follicle cells are not disrupted in asund93 egg chambers

In addition to the functions reported for dynein within the germ cells, two major functions have been identified for dynein within the somatic follicle cells: dynein is required for the normal polarization of the epithelial follicle cells as well as for the normal migration of the border cells (Horne-Badovinac and Bilder, 2008; Van de Bor et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012). To determine if ASUN is required for dynein functions within the follicle cells, we assessed whether asund93 egg chambers exhibited defects in these processes. We observed normal localizations of aPKC, which marks the apical surface of follicle cells, and of Perlecan, which marks the basal surface of follicle cells, in asund93 egg chambers compared to wild-type egg chambers (Fig. S7A–D′; 161/163 asund93 egg chambers and 142/142 wild-type egg chambers with normal aPKC localization; 149/149 asund93 egg chambers and 141/141 wild-type egg chambers with normal Perlecan localization). We additionally determined that the border cells migrated normally to the border between the nurse cells and the oocyte in stage 10 asund93 egg chambers compared to wild-type egg chambers (Fig. S7E–F′; 132/132 asund93 egg chambers and 134/134 wild-type egg chambers).

DISCUSSION

We report herein that asun is a critical regulator of Drosophila oogenesis. Drosophila females that are homozygous for a null allele of asun (asund93) have highly reduced egg-laying rates as a result of defects in oogenesis as well as in processes downstream of oogenesis. We have focused in this study on characterizing the oogenesis defects in asund93 females and have found that eggs laid by these females are ventralized. This phenotype may be secondary to the improper localization of mRNA transcripts encoding the dorsal fate determinant, Grk, in asund93 oocytes. The dynein motor, which is required for transport of grk mRNA during Drosophila oogenesis, is also mislocalized in a significant fraction of asund93 oocytes. We have also determined that other reported dynein-mediated processes such as nuclear positioning, nucleus-centrosome coupling, and centrosome migration are also defective in asund93 egg chambers.

We previously identified ASUN as a regulator of dynein localization during Drosophila spermatogenesis and in cultured human cells (Anderson et al., 2009; Jodoin et al., 2012). Loss of ASUN in Drosophila spermatocytes results in the loss of perinuclear localization of dynein at the G2-M transition, leading to defects in coupling between the nucleus and centrosomes, spindle assembly, chromosome segregation, and cytokinesis during the meiotic divisions (Anderson et al., 2009). Similar defects were observed in mitotically dividing cultured human cells following siRNA-mediated down-regulation of the human homologue of ASUN (Jodoin et al., 2012).

The role of dynein during Drosophila oogenesis has been well characterized. Within the germ cells, the dynein motor has been implicated in maintaining fusome integrity, centrosome migration, and oocyte determination within the germarium (Bolivar et al., 2001; McGrail and Hays, 1997; Mische et al., 2008; Swan et al., 1999). Additionally, dynein is critical for the transport and normal localizations of various patterning factors throughout oogenesis as well as maintenance of the anterior-dorsal positioning of the oocyte nucleus in late-stage egg chambers (Clark et al., 2007; Duncan and Warrior, 2002; Januschke et al., 2002; Lan et al., 2010; Lei and Warrior, 2000; Rom et al., 2007; Swan et al., 1999). Within the somatic follicle cells, dynein plays a role in maintaining apical-basal polarity as well as in the migration of border cells (Horne-Badovinac and Bilder, 2008; Van de Bor et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012).

We have observed disruption of several of these dynein-regulated processes in asund93 ovaries, likely as a result of the loss of dynein localization that occurs in the absence of ASUN. asund93 ovaries exhibit defects in centrosome migration, grk mRNA localization, and nuclear positioning. asund93 ovaries exhibit additional defects in the structure of the egg chamber and in the coupling between the oocyte nucleus and centrosomes. Dynein has been shown to facilitate nucleus-centrosome coupling in other systems, fused egg chambers have been observed in Drosophila dynein light chain mutants, and the displacement of nurse cells toward the oocyte has been reported in ovaries from flies mutant for Bicaudal-D, a known regulator of dynein; thus, these defects of asund93 egg chambers could potentially also be due to loss of dynein function (Anderson et al., 2009; Bolhy et al., 2011; Dick et al., 1996; Jodoin et al., 2012; Malone et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 1999; Sitaram et al., 2012; Splinter et al., 2010; Swan and Suter, 1996).

In spite of the complete loss of ASUN in asund93 egg chambers, we found that certain dynein-mediated processes that have been reported to occur during Drosophila oogenesis were not affected in asund93 ovaries. The fusome, a cytoplasmic organelle, is highly disorganized in ovaries that lack dynein or its accessory factor, LIS-1 (Bolivar et al., 2001; McGrail and Hays, 1997). The normal asymmetric distribution of the fusome within the different cells of a female germline cyst plays an important role in the determination of the future oocyte (de Cuevas and Spradling, 1998; Lin and Spradling, 1995; McKearin, 1997). Not surprisingly, Drosophila lines mutant for dynein or LIS-1 exhibit defects in oocyte determination (McGrail and Hays, 1997; Mische et al., 2008; Swan et al., 1999). We observed, however, that fusome structure within asund93 germaria was indistinguishable from that of wild-type females, and oocyte determination appeared to occur normally in asund93 ovaries (P.S. and L.A.L., unpublished observations). The migration of centrosomes from the nurse cells into the oocyte within the germaria is considered to be a fusome-dependent process (Bolivar et al., 2001; Grieder et al., 2000). Despite our observations of wild-type fusome structure in asund93 germaria, they exhibit defects in centrosome migration. This discrepancy suggests that either an additional factor required for centrosome migration is affected in asund93 mutants, the function (but not structure) of the fusome is compromised in asund93 germaria, or that the fusomes of asund93 germaria have subtle structural defects that we were unable to detect. In addition to being required only for a subset of dynein-dependent processes within germ cells during Drosophila oogenesis, ASUN appears to be dispensable for the functions of dynein within follicle cells, as asund93 egg chambers do not exhibit any defects within these cells.

asund93-derived embryos exhibit defects in dorsal-ventral patterning. We found that the localization of grk mRNA to the anterior-dorsal region of the oocyte is lost in late-stage asund93 egg chambers, suggesting that the ventralization of asund93-derived eggs could be a consequence of this defect. Additionally we observed that 21% of asund93 egg chambers exhibited mild defects in the localization of the Grk protein. This result corresponds well with the percent of asund93-derived embryos exhibiting complete ventralization (23% of asund93-derived embryos). Our results suggest that even a mild disruption of Grk protein localization might lead to severe consequences in the dorsal-ventral patterning of the embryo. We speculate that the partial ventralization that we observed in 31% of asund93-derived embryos could be a result of milder, undetected defects in Grk protein localization. Alternatively, the function of the Grk protein could be compromised due to its dissociation from the oocyte nucleus as a result of nuclear mislocalization in late-stage asund93 egg chambers. Similar defects in the localization of grk mRNA as well as the dissociation between Grk protein and the oocyte nucleus have been reported in Drosophila females mutant for a dynein light chain (Rom et al., 2007). Furthermore, additional unknown defects within the signaling cascade activated by the Grk ligand might exist within the dorsal-anterior follicle cells in asund93 egg chambers that could contribute to the ventralization phenotype.

The oogenesis defects reported herein for asund93 females appear to be only partially penetrant. Centrosome migration, which was the most penetrant ovarian phenotype that we observed (with 65% of germaria showing defects), occurs at a relatively early stage of oogenesis. The remaining defects reported in asund93 egg chambers and asund93-derived embryos had a maximum penetrance of ~50%, with some, such as the structural defects of egg chambers, occurring at a frequency of less than 20%. In contrast, the defects observed in asund93 testes are generally present at a higher frequency (Sitaram et al., 2012). Additionally, we observed that females that are heterozygous for the null allele of asun as well as females that are homozygous for a weak allele of asun (asunf02815) do not exhibit any obvious defects in oogenesis, whereas spermatogenesis is severely compromised in asunf02815 males (P.S. and L.A.L., unpublished observations) (Anderson et al., 2009). Taken together, these data suggest that either ASUN plays a less critical role during Drosophila oogenesis in comparison to spermatogenesis and/or that other factors can better compensate for the loss of ASUN in this system.

ASUN has also been identified as a functional component of an evolutionarily conserved nuclear complex known as the Integrator in cultured mammalian cells (Chen et al., 2012; Malovannaya et al., 2010). Integrator, which is composed of at least 14 distinct subunits (including ASUN), mediates 3′-end processing of small nuclear RNAs (Baillat et al., 2005; Chen and Wagner, 2010). We have recently determined that several Integrator subunits, like ASUN, are required in cultured human cells for recruitment of dynein motors to the nuclear envelope during mitosis (J.N. Jodoin and L.A.L., unpublished observations). Our current model for the role of ASUN in controlling dynein localization is that ASUN, in conjunction with other subunits of the Integrator complex, mediates the proper processing of a specific mRNA target encoding a critical regulator of dynein recruitment to the nuclear envelope in cultured human cells. The high degree of conservation between Drosophila ASUN and its human homologue, and our data showing that Drosophila ASUN can be used to rescue loss of mammalian ASUN and vice versa, makes it likely that Drosophila ASUN functions in a similar manner to regulate the localization of dynein during oogenesis and spermatogenesis (Anderson et al., 2009; Jodoin et al., 2012).

In addition to the defects in oogenesis that we report herein, the capacity of asund93 females to produce mature eggs that accumulate within the ovary suggests that these females also have defects downstream of oogenesis. Given that we have been able to ascribe a majority of the defects in asund93 mutants to disruption of dynein-mediated processes, it is possible that these downstream phenotypes of asund93 females may represent novel functions of dynein. Alternatively, these processes may be directly regulated by ASUN or by a different target of the ASUN/Integrator complex. It would therefore be of importance in future studies to determine if ASUN functions as a component of the Integrator complex in this system, and if so, to identify the targets of this complex required for normal progression through Drosophila oogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Females null for asun (asund93) have a severe egg-laying defect.

asund93-derived embryos are ventralized due to mis-localization of grk transcripts.

Dynein, required for grk localization, is mis-localizaed in asund93 egg chambers.

asund93 ovaries exhibit defects in known dynein-mediated processes.

ASUN regulates dynein and dynein-mediated processes during Drosophila oogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry Orr-Weaver, Tom Hays, Jordan Raff, and Andrea Page-McCaw for providing fly stocks, antibodies, and cDNA. Michael Anderson performed an initial characterization of asund93 phenotypes. Andrea Page-McCaw and Wei Li provided expert advice on in situ hybridization methods, and Andrea Page-McCaw provided the use of her lab’s microscope and camera for performing these experiments. We thank Xiaoxi Wang for expert help with ovary immunofluorescence methods. National Institutes of Health grant GM074044 (to L.A.L.) supported this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson MA, Jodoin JN, Lee E, Hales KG, Hays TS, Lee LA. Asunder is a critical regulator of dynein-dynactin localization during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2709–2721. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillat D, Hakimi MA, Naar AM, Shilatifard A, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Integrator, a multiprotein mediator of small nuclear RNA processing, associates with the C-terminal repeat of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2005;123:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastock R, St Johnston D. Drosophila oogenesis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R1082–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becalska AN, Gavis ER. Lighting up mRNA localization in Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2009;136:2493–2503. doi: 10.1242/dev.032391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhy S, Bouhlel I, Dultz E, Nayak T, Zuccolo M, Gatti X, Vallee R, Ellenberg J, Doye V. A Nup133-dependent NPC-anchored network tethers centrosomes to the nuclear envelope in prophase. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:855–871. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar J, Huynh JR, Lopez-Schier H, Gonzalez C, St Johnston D, Gonzalez-Reyes A. Centrosome migration into the Drosophila oocyte is independent of BicD and egl, and of the organisation of the microtubule cytoskeleton. Development. 2001;128:1889–1897. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ezzeddine N, Waltenspiel B, Albrecht TR, Warren WD, Marzluff WF, Wagner EJ. An RNAi screen identifies additional members of the Drosophila Integrator complex and a requirement for cyclin C/Cdk8 in snRNA 3′-end formation. RNA. 2012;18:2148–2156. doi: 10.1261/rna.035725.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wagner EJ. snRNA 3′ end formation: the dawn of the Integrator complex. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:1082–1087. doi: 10.1042/BST0381082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Meignin C, Davis I. A Dynein-dependent shortcut rapidly delivers axis determination transcripts into the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2007;134:1955–1965. doi: 10.1242/dev.02832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Spradling AC. Morphogenesis of the Drosophila fusome and its implications for oocyte specification. Development. 1998;125:2781–2789. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick T, Ray K, Salz HK, Chia W. Cytoplasmic dynein (ddlc1) mutations cause morphogenetic defects and apoptotic cell death in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1966–1977. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JE, Warrior R. The cytoplasmic dynein and kinesin motors have interdependent roles in patterning the Drosophila oocyte. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1982–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenger DD, Carminati JL, Burney-Sigman DL, Kashevsky H, Dines JL, Elfring LK, Orr-Weaver TL. PAN GU: a protein kinase that inhibits S phase and promotes mitosis in early Drosophila development. Development. 2000;127:4763–4774. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reyes A, Elliott H, St Johnston D. Polarization of both major body axes in Drosophila by gurken-torpedo signalling. Nature. 1995;375:654–658. doi: 10.1038/375654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder NC, de Cuevas M, Spradling AC. The fusome organizes the microtubule network during oocyte differentiation in Drosophila. Development. 2000;127:4253–4264. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnowski EM, Srayko M. Visualization of dynein-dependent microtubule gliding at the cell cortex: implications for spindle positioning. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:377–386. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar S, Mesngon MT, Guillotte AM, Desai B, Ayala R, Smith DS. Lis1 and Ndel1 influence the timing of nuclear envelope breakdown in neural stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1063–1071. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook P, Vallee RB. The dynein family at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4369–4371. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne-Badovinac S, Bilder D. Dynein regulates epithelial polarity and the apical localization of stardust A mRNA. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Wang HL, Qi ST, Wang ZB, Tong JS, Zhang QH, Ouyang YC, Hou Y, Schatten H, Qi ZQ, Sun QY. DYNLT3 is required for chromosome alignment during mouse oocyte meiotic maturation. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:983–989. doi: 10.1177/1933719111401664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januschke J, Gervais L, Dass S, Kaltschmidt JA, Lopez-Schier H, St Johnston D, Brand AH, Roth S, Guichet A. Polar transport in the Drosophila oocyte requires Dynein and Kinesin I cooperation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1971–1981. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodoin JN, Shboul M, Sitaram P, Zein-Sabatto H, Reversade B, Lee E, Lee LA. Human Asunder promotes dynein recruitment and centrosomal tethering to the nucleus at mitotic entry. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:4713–4724. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan L, Lin S, Zhang S, Cohen RS. Evidence for a transport-trap mode of Drosophila melanogaster gurken mRNA localization. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LA, Elfring LK, Bosco G, Orr-Weaver TL. A genetic screen for suppressors and enhancers of the Drosophila PAN GU cell cycle kinase identifies cyclin B as a target. Genetics. 2001;158:1545–1556. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.4.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LA, Lee E, Anderson MA, Vardy L, Tahinci E, Ali SM, Kashevsky H, Benasutti M, Kirschner MW, Orr-Weaver TL. Drosophila genome-scale screen for PAN GU kinase substrates identifies Mat89Bb as a cell cycle regulator. Dev Cell. 2005;8:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Warrior R. The Drosophila Lissencephaly1 (DLis1) gene is required for nuclear migration. Dev Biol. 2000;226:57–72. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, McGrail M, Serr M, Hays TS. Drosophila cytoplasmic dynein, a microtubule motor that is asymmetrically localized in the oocyte. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1475–1494. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Spradling AC. Fusome asymmetry and oocyte determination in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1995;16:6–12. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020160104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Yue L, Spradling AC. The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development. 1994;120:947–956. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall N, Clark A, MacDougall E, Davis I. Drosophila gurken (TGFalpha) mRNA localizes as particles that move within the oocyte in two dynein-dependent steps. Dev Cell. 2003;4:307–319. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CJ, Misner L, Le Bot N, Tsai MC, Campbell JM, Ahringer J, White JG. The C. elegans hook protein, ZYG-12, mediates the essential attachment between the centrosome and nucleus. Cell. 2003;115:825–836. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malovannaya A, Li Y, Bulynko Y, Jung SY, Wang Y, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW, Qin J. Streamlined analysis schema for high-throughput identification of endogenous protein complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2431–2436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrail M, Hays TS. The microtubule motor cytoplasmic dynein is required for spindle orientation during germline cell divisions and oocyte differentiation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124:2409–2419. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKearin D. The Drosophila fusome, organelle biogenesis and germ cell differentiation: if you build it. Bioessays. 1997;19:147–152. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mische S, He Y, Ma L, Li M, Serr M, Hays TS. Dynein light intermediate chain: an essential subunit that contributes to spindle checkpoint inactivation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4918–4929. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman-Silberberg FS, Schupbach T. The Drosophila dorsoventral patterning gene gurken produces a dorsally localized RNA and encodes a TGF alpha-like protein. Cell. 1993;75:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri F, Roth S. Combined activities of Gurken and decapentaplegic specify dorsal chorion structures of the Drosophila egg. Development. 2000;127:841–850. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokrywka NJ, Stephenson EC. Microtubules mediate the localization of bicoid RNA during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 1991;113:55–66. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Wojcik EJ, Sanders MA, McGrail M, Hays TS. Cytoplasmic dynein is required for the nuclear attachment and migration of centrosomes during mitosis in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:597–608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.3.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rom I, Faicevici A, Almog O, Neuman-Silberberg FS. Drosophila Dynein light chain (DDLC1) binds to gurken mRNA and is required for its localization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1526–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salina D, Bodoor K, Eckley DM, Schroer TA, Rattner JB, Burke B. Cytoplasmic dynein as a facilitator of nuclear envelope breakdown. Cell. 2002;108:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F, Bohmann K, Nusslein-Volhard C. The molecular motor dynein is involved in targeting swallow and bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of Drosophila oocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/35008601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T. Germ line and soma cooperate during oogenesis to establish the dorsoventral pattern of egg shell and embryo in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 1987;49:699–707. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen J, Goltz JS, Stevens L, Stein D. Spatially restricted expression of pipe in the Drosophila egg chamber defines embryonic dorsal-ventral polarity. Cell. 1998;95:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamanski FL, Orr-Weaver TL. The Drosophila plutonium and pan gu genes regulate entry into S phase at fertilization. Cell. 1991;66:1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitaram P, Anderson MA, Jodoin JN, Lee E, Lee LA. Regulation of dynein localization and centrosome positioning by Lis-1 and asunder during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development. 2012;139:2945–2954. doi: 10.1242/dev.077511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter D, Tanenbaum ME, Lindqvist A, Jaarsma D, Flotho A, Yu KL, Grigoriev I, Engelsma D, Haasdijk ED, Keijzer N, Demmers J, Fornerod M, Melchior F, Hoogenraad CC, Medema RH, Akhmanova A. Bicaudal D2, dynein, and kinesin-1 associate with nuclear pore complexes and regulate centrosome and nuclear positioning during mitotic entry. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. Developmental Genetics of Oogenesis, The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Plainview, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbings L, Grimes BR, Bownes M. A testis-specifically expressed gene is embedded within a cluster of maternally expressed genes at 89B in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s004270050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuchell-Brereton MD, Siglin A, Li J, Moore JK, Ahmed S, Williams JC, Cooper JA. Functional interaction between dynein light chain and intermediate chain is required for mitotic spindle positioning. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2690–2701. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Spradling AC. Ovulation in Drosophila is controlled by secretory cells of the female reproductive tract. Elife. 2013;2:e00415. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susalka SJ, Pfister KK. Cytoplasmic dynein subunit heterogeneity: implications for axonal transport. J Neurocytol. 2000;29:819–829. doi: 10.1023/a:1010995408343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter B, Steward R. Requirement for phosphorylation and localization of the Bicaudal-D protein in Drosophila oocyte differentiation. Cell. 1991;67:917–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A, Nguyen T, Suter B. Drosophila Lissencephaly-1 functions with Bic-D and dynein in oocyte determination and nuclear positioning. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:444–449. doi: 10.1038/15680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A, Suter B. Role of Bicaudal-D in patterning the Drosophila egg chamber in mid-oogenesis. Development. 1996;122:3577–3586. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurkauf WE, Smiley S, Wong ML, Alberts BM. Reorganization of the cytoskeleton during Drosophila oogenesis: implications for axis specification and intercellular transport. Development. 1992;115:923–936. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk C, Schupbach T. Versatility in signalling: multiple responses to EGF receptor activation during Drosophila oogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Bor V, Zimniak G, Cerezo D, Schaub S, Noselli S. Asymmetric localisation of cytokine mRNA is essential for JAK/STAT activation during cell invasiveness. Development. 2011;138:1383–1393. doi: 10.1242/dev.056184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy L, Orr-Weaver TL. The Drosophila PNG kinase complex regulates the translation of cyclin B. Dev Cell. 2007;12:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainman A, Creque J, Williams B, Williams EV, Bonaccorsi S, Gatti M, Goldberg ML. Roles of the Drosophila NudE protein in kinetochore function and centrosome migration. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1747–1758. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman JD, Freeman M. An autoregulatory cascade of EGF receptor signaling patterns the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1998;95:355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Inaki M, Cliffe A, Rorth P. Microtubules and Lis-1/NudE/dynein regulate invasive cell-on-cell migration in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Graham OS, Raposo A, St Johnston D. Growing microtubules push the oocyte nucleus to polarize the Drosophila dorsal-ventral axis. Science. 2012;336:999–1003. doi: 10.1126/science.1219147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.